Power-to-Gas

Power-to-gas이 문서는 갱신할 필요가 있습니다.(2020년 7월) |

Power-to-Gas(종종 P2G)[1]는 전력을 사용하여 가스 연료를 생산하는 기술입니다.풍력 발전의 잉여 전력을 사용할 때, 그 개념은 때때로 풍력 가스라고 불립니다.

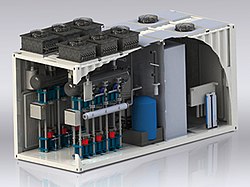

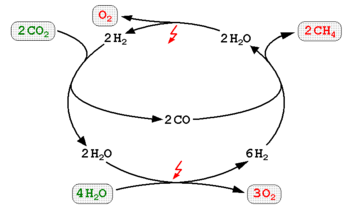

대부분의 P2G 시스템은 수소를 생산하기 위해 전기 분해를 사용한다.수소는 [2]직접 사용할 수 있으며, 추가 단계(2단계 P2G 시스템으로 알려져 있음)는 수소를 신가스, [3]메탄 또는 [4]LPG로 변환할 수 있다.가역성 고체 산화물 세포([5]rSOC) 기술과 같은 메탄을 생산하기 위한 1단계 P2G 시스템도 존재합니다.

가스는 화학적 공급 원료로 사용될 수도 있고,[6] 가스 터빈과 같은 기존 발전기를 사용하여 전기로 다시 전환될 수도 있습니다.전력 대 가스는 전기의 에너지를 압축 가스의 형태로 저장 및 운반할 수 있도록 하며, 천연 가스의 장기 운송 및 저장을 위해 기존 인프라를 사용하는 경우가 많습니다.P2G는 종종 계절적 재생 에너지 [7][8]저장에 가장 유망한 기술로 여겨진다.

에너지 저장 및 수송

전력 대 가스 시스템은 풍력 공원 또는 태양광 발전소의 부속품으로 배치될 수 있다.풍력 발전기나 태양열 어레이에 의해 생성된 초과 전력 또는 오프피크 전력은 몇 시간, 며칠 또는 몇 달 후에 전기 그리드에 대한 전력을 생산하기 위해 사용될 수 있다.독일의 경우, 천연가스로 전환하기 전에, 가스 네트워크는 50-60%가 수소로 구성된 도시 가스를 사용하여 운영되었습니다.독일 천연가스 네트워크의 저장 용량은 200,000 GWh 이상이며, 이는 수개월의 에너지 요구량에 충분합니다.이에 비해 독일의 모든 양수 발전소의 용량은 약 40GWh에 [citation needed]불과하며, 천연가스 저장은 빅토리아 시대부터 존재해 온 성숙한 산업이다.독일의 저장/검색 전력 요건은 2023년 16GW, 2033년 80GW, [9]2050년 130GW로 추정된다.킬로와트시당 저장 비용은 수소의 경우 0.10유로, [10]메탄의 경우 0.15유로로 추정됩니다.

기존 천연가스 수송 인프라는 파이프라인을 이용해 막대한 양의 가스를 장거리 수송할 수 있다.LNG 수송선을 이용해 대륙 간에 천연가스를 수송하는 것은 이제 이익이 된다.가스 네트워크를 통한 에너지 전송은 전기 전송 네트워크(8%)보다 훨씬 적은 손실(0.1%)로 이루어집니다.이 인프라는 P2G에 의해 생성된 메탄을 수정 없이 운반할 수 있다.수소로도 사용할 수 [citation needed]있을 것이다.수소를 위한 기존 천연가스 파이프라인의 사용은 EU NaturalHy[11] 프로젝트와 미국 에너지부(DOE)[12]에 의해 연구되었다.블렌딩 기술은 HCNG에도 사용된다.

효율성.

2013년에는 복합 사이클 발전소를 사용하여 수소 경로가 최대 43%, 메탄 39%의 효율에 도달할 수 있는 등 전력-가스 저장소의 왕복 효율이 50%를 훨씬 밑돌았다.전력과 열을 모두 생산하는 열병합 발전소를 사용할 경우 효율은 60%를 초과할 수 있지만 펌프식 수력이나 배터리 [13]저장 공간보다는 여전히 부족합니다.그러나 P2G(Power-to-Gas) 스토리지의 효율성을 높일 수 있습니다.2015년 Energy and Environment Science에 발표된 연구에 따르면, 가역성 고체 산화물 전지를 사용하고 저장 과정에서 폐열을 재활용함으로써 70%를 초과하는 전기-전기 왕복 효율을 저비용으로 [14]달성할 수 있습니다.또한, 가압 가역 고체 산화물 셀과 유사한 방법론을 사용한 2018년 연구에 따르면 최대 80%의 왕복 효율성(전력 대 전력)이 [15]실현 가능할 수 있습니다.

| 연료 | 효율성. | 조건들 |

|---|---|---|

| 경로:전기→가스 | ||

| 수소 | 54–72 % | 200bar 압축 |

| 메탄(SNG) | 49–64 % | |

| 수소 | 57–73 % | 80bar 압축(천연가스 파이프라인) |

| 메탄(SNG) | 50–64 % | |

| 수소 | 64–77 % | 압축하지 않고 |

| 메탄(SNG) | 51–65 % | |

| 경로:전기→가스→전기 | ||

| 수소 | 34–44 % | 80bar의 압축으로 최대 60%의 전력 절약 |

| 메탄(SNG) | 30–38 % | |

| 경로:전기→가스→전기 및 열(열병합) | ||

| 수소 | 48–62 % | 80bar 압축 및 전기/열(40/45%) |

| 메탄(SNG) | 43–54 % | |

전기 분해 기술

- 전기 분해 [17]기술의 상대적인 장점과 단점.

| 장점 | 단점 |

|---|---|

| 상용 테크놀로지(하이테크놀로지 적성 레벨) | 제한된 비용 절감 및 효율성 개선 가능성 |

| 저투자 전해조 | 높은 유지보수 강도 |

| 대규모 스택 사이즈 | 반응성, 램프 레이트 및 유연성(최소 부하 20%) |

| 극히 낮은 수소 불순물(0.001%) | 250kW 미만의 스택에는 일반적이지 않은 AC/DC 컨버터가 필요 |

| 명목상 작동하지 않을 경우 부식성 전해질이 저하됨 |

| 장점 | 단점 |

|---|---|

| 신뢰성 높은 테크놀로지(속도론 없음)와 심플하고 콤팩트한 설계 | 높은 투자 비용(귀금속, 막) |

| 매우 빠른 응답 시간 | 막의 수명 제한 |

| 비용 절감 가능성(모듈형 설계) | 높은 수분 순도 필요 |

| 장점 | 단점 |

|---|---|

| 최고의 전해 효율 | 매우 낮은 기술 준비 수준(개념 증명) |

| 낮은 자본 비용 | 고온 및 재료 안정성에 영향을 미치기 때문에 수명이 짧습니다. |

| 화학적 메탄화와의 통합 가능성(열 재활용) | 제한된 유연성, 일정한 부하 필요 |

수소화 전력

현재의 모든 P2G 시스템은 전기를 사용하여 전기 분해를 통해 물을 수소와 산소로 나눕니다."수소 전력" 시스템에서는 생성된 수소가 천연 가스 그리드에 주입되거나 다른 [2]유형의 가스를 생산하는 데 사용되는 대신 운송 또는 산업에 사용됩니다.

ITM Power는 2013년 3월 Thüga Group 프로젝트의 입찰을 따내 360kW의 자기 가압식 고압 전해 신속 응답 프로톤 교환막(PEM) 전해서 급속 반응 전기 분해 전력 대 가스 에너지 저장 플랜트를 공급했습니다.이 장치는 하루에 125kg의 수소 가스를 생산하며 AEG 전력 전자 장치를 통합합니다.그것은 헤센 주에 있는 프랑크푸르트 쉴레스트라에 있는 마이노바 AG 부지에 위치할 것이다.운영 데이터는 Thüga 그룹 전체가 공유합니다.Thüga 그룹은 약 100명의 지방 공공 사업회원을 보유한 독일 최대 규모의 에너지 기업 네트워크입니다.그 프로젝트 협력자들:, 제조 업체 kg, Erdgas Mittelsachsen 회사, Energieversorgung Mittelrhein 회사,schwaben 회사, Gasversorgung Westerwald 회사, Mainova Aktiengesellschaft, Stadtwerke 안스 바흐 회사, Stadtwerke 나쁜 Hersfeld 회사, Thüga Energienetze 회사, WEMAG AG는,e-rp 회사, ESWE Versorgungs AGThüga Aktiengesellschaft과 erdgasbadenova AG및 포함한다.~하듯이프로젝트 코디네이터.과학 파트너가 운영 단계에 [18]참여할 것입니다.시간당 60입방미터의 수소를 생산할 수 있고 수소로 농축된 3,000입방미터의 천연가스를 시간당 그리드에 공급할 수 있습니다.2016년부터 시범공장을 증설하여 생산된 수소를 메탄으로 완전히 전환하여 천연가스 [19]그리드에 직접 주입할 수 있도록 할 계획이다.

2013년 12월 ITM Power, Mainova, NRM Netzdienste Lin-Main GmbH는 고속 응답 양성자 교환막 전해장치인 ITM Power HGas를 사용하여 독일 가스배전망에 수소 주입을 시작했습니다.전해장치의 소비전력은 315킬로와트입니다.시간당 약 60입방미터의 수소를 생산하기 때문에 1시간 안에 3,000입방미터의 수소 농축 천연가스를 [20]네트워크에 공급할 수 있다.

2013년 8월 28일 E.온 한세, 솔비코어, 스위스 가스는 독일 팔크하겐에서 상업용 가스 공급 장치를 출범시켰다.2메가와트 용량의 이 장치는 [21]시간당 360입방미터의 수소를 생산할 수 있다.이 발전소는 풍력과 수소[22] 전기 분해 장비를 사용하여 물을 수소로 변환하고, 수소는 기존 지역 천연가스 전송 시스템에 주입됩니다.스위스 가스는 100개 이상의 천연가스 사업체를 대표하고 있으며 20%의 자본 지분을 보유하고 있으며 생산된 가스의 일부를 구매하기로 합의하고 있다.두 번째 800kW 전력[23] 대 가스 프로젝트가 함부르크/Reitbrook 지역에서 시작되었으며 [24]2015년에 시작될 예정입니다.

2013년 8월, E사가 소유한 메클렌버그-포어포메른의 Graphzow에 있는 140 MW의 윈드 파크.ON은 전해조를 받았다.생성된 수소는 내연기관에서 사용하거나 로컬 가스 그리드에 주입할 수 있습니다.수소 압축 및 저장 시스템은 최대 27MWh의 에너지를 저장하며, 그렇지 않으면 [25]낭비될 수 있는 풍력 에너지를 이용하여 윈드 파크의 전반적인 효율성을 높입니다.전해서는 210Nm3/h의 수소를 생성하며 RH2-WKA에 [26]의해 작동됩니다.

INGRID 프로젝트는 2013년 이탈리아 풀리아에서 시작되었다.스마트 그리드 모니터링 및 [27]제어를 위한 39 MWh 스토리지와 1.2 MWh 전해장치를 갖춘 4년 프로젝트입니다.수소는 그리드 밸런싱, 운송, 산업 및 가스 네트워크 [28]주입에 사용됩니다.

독일[29] 브란덴부르크에 있는 12MW 프레즐라우 윈드파크의 잉여 에너지는 2014년부터 가스망에 주입된다.

독일 마인츠에 있는 스타트베르케 마인츠, 라인메인 응용과학대학, 린데, 지멘스의 6MW 에너지파크[30] 마인츠가 2015년에 문을 열 예정이다.

재생 에너지 저장 및 활용을 위한 가스로의 전력 및 기타 에너지 저장 계획은 독일의 에너지 전환 프로그램(Energy Viewende, Energy Transition Program)[31]의 일부이다.

프랑스에서는 AFUL 샹트리에(Federation of Local Utilities Association)의 MINERVE 데모 참가자가 선출된 대표자, 기업 및 보다 일반적으로 시민사회와 함께 미래를 위한 에너지 솔루션 개발을 촉진하는 것을 목표로 하고 있다.그것은 다양한 원자로와 촉매로 실험하는 것을 목표로 한다.MINERVE 시연기(CH의4 0.6Nm3/h)에 의해 생성된 합성 메탄은 AFUL Chantrerie 보일러 공장의 보일러에 사용되는 CNG 연료로 회수된다.설치는 Leaf의 지원을 받아 프랑스 SME Top Industrie에 의해 설계 및 구축되었습니다.2017년 11월에는 CH의 934.3%로 예상 실적을 달성했습니다.이 프로젝트는 ADEME 및 ERDF-Pays de Loire 지역 및 기타 여러 파트너(콘세일 데파르트멘탈 드 루아르-Atlantic, Engie-Cofely, GRDF, GRTGAZ, 낭트-메트로폴리스, 시델라 및 Sydev)[32]에 의해 지원되었습니다.

압축 없는 그리드 주입

이 시스템의 핵심은 양성자 교환막(PEM) 전해조입니다.전해기는 전기에너지를 화학에너지로 변환하여 전기의 저장을 용이하게 합니다.가스혼합공장은 천연가스 흐름에서 수소의 비율이 부피 기준 2%를 넘지 않도록 하며, 이는 천연가스 충전소가 국지적 유통망에 위치할 때 기술적으로 허용되는 최대값이다.전해기는 수소-메탄 혼합물을 가스 분배망과 동일한 압력(3.5bar)으로 공급합니다.[33]

파워 투 메탄

Apower-to-methane 시스템은 power-to-hydrogen 시스템에서가 이산화 탄소와 사바티에 반응이나 또는 생물학적 메탄 생성 8%,[표창 필요한]의 메탄은 천연 가스 그리드 만약 월에 입력할 수 있는 여분의 에너지 변환 손실을 초래와 같은 메탄 생성 반응을 이용한 methane[34](천연 가스를 참조하십시오)를 생산하기 위해 수소 결합한 것이다.e순도 유지 요건도달했습니다.[35]

태양광 및 수소연구센터(ZSW)와 솔라퓨얼 GmbH(현 ETOGAS GmbH)는 독일 [36]슈투트가르트에서 250kW의 전력 입력 전력 시연 프로젝트를 실현했다.이 공장은 2012년 [37]10월 30일에 가동되었다.

최초의 업계 규모의 Power-to-Methane 플랜트는 독일 Werlte에 있는 Audi AG의 ETOGAS에 의해 실현되었습니다.6 MW의 전기 입력 전력을 가진 발전소는 폐기물 바이오가스 발전소의 CO와 간헐적 재생 가능 전력을 사용하여2 지역 가스 그리드(EWE에 의해 [38]운영됨)에 직접 공급되는 합성 천연가스(SNG)를 생산하고 있다.이 발전소는 Audi e-연료 프로그램의 일부이다.Audi e-gas라는 이름의 합성 천연가스는 표준 CNG 차량으로 CO-중립적인 이동성을 가능하게2 합니다.현재 아우디의 첫 CNG 차량인 Audi A3 g-tron의 [39]고객이 이용할 수 있다.

2014년 4월, 유럽연합의 공동 자금조달 및 KIT 조정[40][41] HELMETH(Integrated High-Temperature ELectrolex and Methanation for Effective Power to Gas Conversion) 연구 프로젝트가 시작되었습니다.[42]이 프로젝트의 목적은 고온 전해(SOEC) 기술과 CO-메탄화를2 열적으로 통합함으로써 매우 효율적인 Power-to-Gas 기술의 개념 증명입니다.발열 메탄화와 고온 증기 전기분해 변환 효율의 증기 발생의 열적 통합을 통해 이론적으로 85%(사용 전기 에너지당 생산된 메탄의 높은 발열치)가 가능하다.이 프로세스는 가압 고온 증기 전기 분해 및 가압 CO-방법화2 모듈로 구성됩니다.이 프로젝트는 2017년에 완료되었으며 시제품은 76%의 효율성을 달성했으며 산업용 [43]규모 플랜트는 80%의 성장 잠재력을 보였습니다.CO-methanation의2 운전조건은 10~30bar의 가스압력, 1~5.4m3/h(NTP), H < 2 volume-% response로2 SNG를 생성하는 반응물 변환이다.CH4 > 97 volum.[44] - %따라서 생성된 대체천연가스를 독일 전체 천연가스망에 [45]제한 없이 주입할 수 있다.발열반응의 냉각매체로 끓는 물을 약 87bar의 수증기압에 해당하는 최대 300℃에서 사용한다.SOEC는 최대 15bar의 압력과 최대 90%의 증기 변환으로 작동하며 메탄화 공급으로 3.37kWh의 전력에서 1개의 표준 입방미터의 수소를 생성합니다.

Power to Gas의 기술 성숙도는 2016년 3월부터 4년 [46]동안 진행된 유럽 27개 파트너 프로젝트 STORE&GO에서 평가되고 있습니다.3개의 다른 유럽 국가(Falkhagen/Germany, Solothurn/Swits, Troia/Italy)에서 3개의 다른 기술적 개념이 입증되었다.관련된 기술에는 생물학적 및 화학적 메탄화, 대기 중 CO의 직접2 포집, 합성된 메탄에서 바이오-LNG로의 액화, 가스 그리드에 대한 직접 주입 등이 포함된다.이 프로젝트의 전체적인 목표는 기술적,[47] 경제적,[48] 법적 측면에서 이러한 기술과 다양한 사용 경로를 평가하여 단기 및 장기적으로 비즈니스 사례를 식별하는 것입니다.이 프로젝트는 유럽연합의 Horizon 2020 연구 및 혁신 프로그램(1800만 유로)과 스위스 정부(600만 유로)가 공동 출자하고 있으며, 참여 산업 [50]파트너로부터 400만 유로를 추가로 조달하고 있다.전체 프로젝트의 코디네이터는 KIT에 위치한 DVGW의[51] 연구 센터입니다.

미생물 메탄화

생물학적 메탄화는 물의 전기 분해로 수소를 형성하고 이2 수소를 사용하여 메탄으로 CO를 감소시키는 두 가지 과정을 결합합니다.이 과정에서 메탄형성미생물(메탄고세균 또는 메타노겐)은 비촉매전극(음극)의 과전위를 감소시키는 효소를 방출해 [52][53]수소를 생성한다.이 미생물 대 가스 전력 반응은 상온 및 pH 7과 같은 주변 조건에서 일상적으로 80-100%[54][55]에 이르는 효율로 발생합니다.하지만, 낮은 온도 때문에 메탄은 사바티에 반응보다 더 느리게 형성된다.이산화탄소의2 메탄으로의 직접 전환도 상정되어 있어 [56]수소 생산의 필요성을 회피하고 있다.미생물 대 가스 반응에 관여하는 미생물은 전형적으로 메타노박테리아목의 구성원이다.이 반응을 촉매하는 것으로 나타난 속은 메타노박테리움,[57][58] 메타노브레비박테리움,[59] 메타나모박테리움(열호균)[60]이다.

LPG 생산

메탄은 고압 저온에서 부분 역수소화합물과 합성하여 LPG를 제조할 수 있다.LPG는 뛰어난 안티녹 특성을 가지고 있고 깨끗한 [4]연소를 제공하기 때문에 프리미엄 가솔린 블렌딩 스톡인 알킬레이트(Alkylate)로 전환할 수 있습니다.

음식에 대한 파워

전기에서 발생하는 합성 메탄은 육지와 [61][62][63]물 발자국이 작은 메탄균 배양으로 소, 가금류, 어류용 단백질이 풍부한 사료를 경제적으로 생산하는 데도 사용할 수 있다.이들 공장에서 생산되는 이산화탄소는 합성 메탄(SNG) 생성에 재활용될 수 있다.마찬가지로 세균 배양 시 물의 전기분해 및 메탄화 공정에서 생성물로 생성된 산소가스를 소비할 수 있다.이러한 통합 발전소로, 풍부한 재생 가능 태양 에너지와 풍력 발전 잠재력은 수질 오염이나 온실 가스([64]GHG) 배출 없이 고부가가치 식품으로 전환될 수 있다.

바이오메탄으로 바이오가스 업그레이드

세 번째 방법에서는 바이오가스 업그레이드기 후의 목질가스 발생기 또는 바이오가스 플랜트의 출력 중 이산화탄소와 전해자에서 생성된 수소를 혼합하여 메탄을 생성한다.전해조로부터 나오는 자유열은 바이오가스 공장의 난방비를 절감하는 데 사용됩니다.바이오가스가 파이프라인 저장에 사용될 경우,[3] 오염물질인 이산화탄소, 물, 황화수소, 미립자를 제거해야 피해를 막을 수 있다.

2014-Avedöre 폐수 서비스(Denmark)는 1MW 전해조 공장을 추가하여 [65]하수 슬러지에서 혐기성 소화 바이오가스를 업그레이드하고 있습니다.생성된 수소는 사바티에 반응에서 바이오가스의 이산화탄소와 함께 메탄을 생성하기 위해 사용된다.Electrochaea는[66] P2G BioCat 외부에서 생체 촉매 메탄화로 다른 프로젝트를 테스트하고 있다.동사는, 호열성 메타노겐 메타나토모박터 서모토피더스(Methanotomobacter thermautotrophyus)의 적응형 변종을 사용해, 산업 [67]환경에서 실험실 규모의 기술을 실증했습니다.덴마크 [68]풀럼에서는 2013년 1~11월 1만 리터급 원자로 선박을 이용한 상업화 이전 시범사업이 실시됐다.

2016년 Torrgas, Siemens, Stedin, Gasunie, A.Hak, Hanzhogeschool/EnTranCe, Energy Valley는 네덜란드 델프질(델프질)에 12MW의 전력 가스 시설을 열 예정이다. 이 시설은 토르가스(바이오콜)에서 나오는 바이오 가스를 전기 분해 수소로 업그레이드하여 인근 산업 [69]소비자에게 공급할 예정이다.

Power-to-syngas

| 물. | CO2 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 물의 전기 분해 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 산소 | 수소 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 변환 리액터 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 물. | 수소 | CO | |||||||||||||||||||

신가스는 수소와 일산화탄소의 혼합물이다.그것은 빅토리아 시대부터 사용되어 왔으며, 그 때 석탄으로 생산되었고 "타운 가스"로 알려져 있다.동력 대 신가스 시스템은 동력 대 수소 시스템의 수소를 사용하여 신가스를 생성한다.

- 첫 번째 단계:전기분해수(SOEC) - 물은 수소와 산소로 나뉜다.

- 두 번째 단계:RWGSR(Conversion Reactor) -산화탄소 및 이산화탄소는 수소, 일산화탄소, 물을 출력하는 Conversion Reactor의 입력값으로, 3H2 + CO22 → (2H2 +syngas CO) + HO

- 신가스는 신연료를 생산하는데 사용된다.

대처

이산화탄소와 물로부터 신가스를 생성하기 위한 다른 계획들은 다른 물 분할 방법을 사용할 수 있다.

- CSP

- HTE/알칼리성 물 전해

- 2004 Syntroxi Fuels : Idaho National Laboratory and Seramatec, Inc. (미국).[85][86][87][88][89][90]

- 2008 Wind Fuels : 도티 에너지(US).[91][92]

- 2012년 공기연료합성—공기연료합성유한공사(영국).[93][94][95][96][97]공기연료합성유한공사가 [98]파산했다.

- 2013년 그린 피드—BGU 및 이스라엘 전략 대체 에너지 재단(I-SAEF).[99][100][101][102]

- 2014 E-diesel — 청정 기술 회사인 Sunfire와 Audi.[103][104][105]

미국 해군 연구소(해군 연구소)이사회에 sea,[106]의 베이스 제품 탄소 탄소(이산화 탄소)과 물(H2O)바닷물에서 및 모듈 구성 그 연속 어시 더 피케이션 알칼리성 물원 중에서 들어 A."를 통해 파생된 것을 가진 연료 선박을 만들 고온을 이용한 power-to-liquids 시스템을 설계 중는 Reco매우 많은 CO와2 지속적인 수소 가스 생산량"입니다.[107][108]

「 」를 참조해 주세요.

- 탄소 중립 연료

- 전기메탄형성

- 전기 연료

- 전기 수소 생성

- 그리드 에너지 저장소

- 수소 경제

- 메타네이션

- 에너지 저장 프로젝트 목록

- Power-to-X

- 재생 가능한 천연가스

- 수소 기술 연표

메모들

- ^ Bünger, U.; Landinger, H.; Pschorr-Schoberer, E.; Schmidt, P.; Weindorf, W.; Jöhrens, J.; Lambrecht, U.; Naumann, K.; Lischke, A. (11 June 2014). Power to gas in transport-Status quo and perspectives for development (PDF) (Report). Federal Ministry of Transport and Digital Infrastructure (BMVI), Germany. Retrieved 3 June 2021.

- ^ a b Eberle, Ulrich; Mueller, Bernd; von Helmolt, Rittmar (2012). "Fuel cell electric vehicles and hydrogen infrastructure: status 2012". Energy & Environmental Science. 5 (10): 8780. doi:10.1039/C2EE22596D. Archived from the original on 2014-02-09. Retrieved 2014-12-16.

- ^ a b NREL 2013: 천연가스 파이프라인 네트워크에 수소를 혼합: 주요 이슈 검토

- ^ a b "BPN Butane – Propane news". Archived from the original on 30 December 2017. Retrieved 10 April 2017.

- ^ Mogensen MB, Chen M, Frandsen HL, Graves C, Hansen JB, Hansen KV, Hauch A, Jacobsen T, Jensen SH, Skafte TL, Sun X (September 2019). "Reversible solid-oxide cells for clean and sustainable energy". Clean Energy. 3 (3): 175–201. doi:10.1093/ce/zkz023.

over 100 times more solar photovoltaic energy than necessary is readily accessible and that practically available wind alone may deliver sufficient energy supply to the world. Due to the intermittency of these sources, effective and inexpensive energy-conversion and storage technology is needed. Motivation for the possible electrolysis application of reversible solid-oxide cells (RSOCs), including a comparison of power-to-fuel/fuel-to-power to other energy-conversion and storage technologies is presented.

- ^ "EUTurbines". www.poertheeu.eu. EUTurbines.

- ^ Andrews, John; Shabani, Bahman (January 2012). "Re-envisioning the role of hydrogen in a sustainable energy economy". International Journal of Hydrogen Energy. 37 (2): 1184–1203. doi:10.1016/j.ijhydene.2011.09.137.

- ^ Staffell, Iain; Scamman, Daniel; Velazquez Abad, Anthony; Balcombe, Paul; Dodds, Paul E.; Ekins, Paul; Shah, Nilay; Ward, Kate R. (2019). "The role of hydrogen and fuel cells in the global energy system". Energy & Environmental Science. 12 (2): 463–491. doi:10.1039/C8EE01157E.

- ^ Electricity storage in the German energy transition (PDF) (Report). Agora Energiewende. December 2014. Retrieved 2020-02-11.

- ^ "Wind power to hydrogen". hi!tech. Siemens. Archived from the original on 2014-07-14. Retrieved 2014-06-21.

- ^ NaturalHY Project. "Using the Existing Natural Gas System for Hydrogen". EXERGIA. Archived from the original on 2014-10-29. Retrieved 2014-06-21.

- ^ NREL - 천연가스 파이프라인 네트워크에 수소 혼합 주요 이슈 검토

- ^ Volker Quasching, 회생 에너지 시스템. Technologie - Berechnung - 시뮬레이션, Hanser 2013, 페이지 373.

- ^ Jensen; et al. (2015). "Large-scale electricity storage utilizing reversible solid oxide cells combined with underground storage of CO

2 and CH

4". Energy and Environmental Science. 8 (8): 2471–2479. doi:10.1039/c5ee01485a. - ^ Butera, Giacomo; et al. (2019). "A novel system for large-scale storage of electricity as synthetic natural gas using reversible pressurized solid oxide cells" (PDF). Energy. 166: 738–754. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2018.10.079. S2CID 116315454.

- ^ (독일어) Fraunhofer - Energiewirtschaftliche und ökologische Bewertung eines Windgas-Angebotes, 18페이지

- ^ Grond, Lukas; Holstein, Johan (February 2014). "Power-to-gas: Climbing the technology readiness ladder" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 March 2020. Retrieved 3 March 2020.

- ^ "First Sale of 'Power-to-Gas' Plant in Germany –". Archived from the original on 2013-05-02. Retrieved 2013-05-17.

- ^ 프랑크푸르트에 있는 ITM Power-to-Gas 파일럿 플랜트의 지반 파괴 2013-11-11 웨이백 머신에 보관

- ^ "Injection of Hydrogen into the German Gas Distribution Grid –". Archived from the original on 2014-03-08. Retrieved 2013-12-05.

- ^ "E.ON inaugurates power-to-gas unit in Falkenhagen in eastern Germany". e·on (Press release). 2013-08-28. Archived from the original on 2013-09-11.

- ^ "Hydrogenics and Enbridge to develop utility-scale energy storage". Archived from the original on 2013-11-11. Retrieved 2013-11-11.

- ^ "E.on Hanse starts construction of power-to-gas facility in Hamburg". Archived from the original on 2014-03-15. Retrieved 2013-11-19.

- ^ "E.ON power-to-gas pilot unit in Falkenhagen first year of operation". Archived from the original on 2014-11-11. Retrieved 2014-11-10.

- ^ "German wind park with 1 MW Hydrogenics electrolyser for Power-to-Gas energy storage". Renewable Energy Focus. 17 October 2013. Archived from the original on 1 June 2017. Retrieved 21 July 2017.

- ^ "RH2-WKA". Archived from the original on 2013-11-24. Retrieved 2013-11-11.

- ^ "INGRID Project to Launch 1.2 MW Electrolyser with 1 Ton of Storage for Smart Grid Balancing in Italy". Archived from the original on 2013-11-11. Retrieved 2013-11-11.

- ^ "Grid balancing, Power to Gas (PtG)" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2013-11-11. Retrieved 2013-11-11.

- ^ Prenzlau 윈드파크(독일)

- ^ 에네르기파크 마인츠

- ^ Schiermeier, Quirin (April 10, 2013). "Renewable power: Germany's energy gamble: An ambitious plan to slash greenhouse-gas emissions must clear some high technical and economic hurdles". Nature. Archived from the original on April 13, 2013. Retrieved April 10, 2013.

- ^ 를 클릭합니다"Un démonstrateur Power to gas en service à Nantes". Lemoniteur.fr (in French). 2018. Retrieved 9 February 2018..

- ^ "Energiewende & Dekarbonisierung Archive". Archived from the original on 2013-12-05. Retrieved 2013-12-05.

- ^ "DNV-Kema Systems analyses power to gas" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-01-24. Retrieved 2014-08-21.

- ^ Ghaib, Karim; Ben-Fares, Fatima-Zahrae (2018). "Power-to-Methane: A state-of-the-art review" (PDF). Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews. 81: 433–446. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2017.08.004. Retrieved 1 May 2018.

- ^ "German network companies join up to build power-to-gas plant". Reuters. 2018-10-16. Archived from the original on 16 October 2018. Retrieved 17 October 2018.

- ^ "Weltweit größte Power-to-Gas-Anlage zur Methan-Erzeugung geht in Betrieb". ZSW-BW.de (in German). Archived from the original on 2012-11-07. Retrieved 2017-12-01.

- ^ "Energy turnaround in the tank". Audi.com. Archived from the original on 2014-06-06. Retrieved 2014-06-03.

- ^ "Company". Audi.com. Archived from the original on 2014-06-06. Retrieved 2014-06-04.

- ^ "Engler-Bunte-Institute Division of Combustion Technology - Project HELMETH". Retrieved 2014-10-31.

- ^ "Project homepage - HELMETH". Retrieved 2014-10-31.

- ^ "Karlsruhe Institute of Technology - Press Release 044/2014". Retrieved 2014-10-31.

- ^ "Karlsruhe Institute of Technology - Press Release 009/2018". Retrieved 2018-02-21.

- ^ "Project homepage - HELMETH". Retrieved 2018-02-21.

- ^ DIN EN 16723-2:2017-10 - Erdgas und Biomethan zur Verwendung im Transportwesen und Biomethan zur Einspeisung in Erdgasnetz

- ^ "Deutscher Verein des Gas und Wasserfaches e.V.: Press release - Project Store&Go". Archived from the original on 2016-08-01. Retrieved 2016-12-12.

- ^ "Watt d'Or 4 all: "Store&Go" – Erdgasnetz als Riesen-Batterie". Archived from the original on 2017-02-21. Retrieved 2016-12-12.

- ^ "Store&Go, Innovative large-scale energy STORagE technologies AND Power-to-Gas concepts after Optimisation". Archived from the original on 2016-11-24. Retrieved 2016-12-12.

- ^ "Het juridische effect van innovatieve energieconversie en –opslag". Retrieved 2016-12-12.

- ^ "Project homepage - STORE&GO". Retrieved 2016-12-12.

- ^ "Deutscher Verein des Gas und Wasserfaches e.V.: Press release - Innovative 28 million E project STORE&GO started to show large scale energy storage by Power-to-Gas is already possible today" (PDF). Retrieved 2016-12-12.

- ^ Deutzmann, Jörg S.; Sahin, Merve; Spormann, Alfred M. (2015). "Deutzmann, J. S.; Sahin, M.; Spormann, A. M., Extracellular enzymes facilitate electron uptake in biocorrosion and bioelectrosynthesis". mBio. 6 (2). doi:10.1128/mBio.00496-15. PMC 4453541. PMID 25900658.

- ^ Yates, Matthew D.; Siegert, Michael; Logan, Bruce E. (2014). "Hydrogen evolution catalyzed by viable and non-viable cells on biocathodes". International Journal of Hydrogen Energy. 39 (30): 16841–16851. doi:10.1016/j.ijhydene.2014.08.015.

- ^ Marshall, C. W.; Ross, D. E.; Fichot, E. B.; Norman, R. S.; May, H. D. (2012). "Electrosynthesis of commodity chemicals by an autotrophic microbial community". Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 78 (23): 8412–8420. doi:10.1128/aem.02401-12. PMC 3497389. PMID 23001672.

- ^ Siegert, Michael; Yates, Matthew D.; Call, Douglas F.; Zhu, Xiuping; Spormann, Alfred; Logan, Bruce E. (2014). "Comparison of Nonprecious Metal Cathode Materials for Methane Production by Electromethanogenesis". ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering. 2 (4): 910–917. doi:10.1021/sc400520x. PMC 3982937. PMID 24741468.

- ^ Cheng, Shaoan; Xing, Defeng; Call, Douglas F.; Logan, Bruce E. (2009). "Direct biological conversion of electric current into methane by electromethanogenesis". Environmental Science. 43 (10): 3953–3958. Bibcode:2009EnST...43.3953C. doi:10.1021/es803531g. PMID 19544913.

- ^ Beese-Vasbender, Pascal F.; Grote, Jan-Philipp; Garrelfs, Julia; Stratmann, Martin; Mayrhofer, Karl J.J. (2015). "Selective microbial electrosynthesis of methane by a pure culture of a marine lithoautotrophic archaeon". Bioelectrochemistry. 102: 50–5. doi:10.1016/j.bioelechem.2014.11.004. PMID 25486337.

- ^ Siegert, Michael; Yates, Matthew D.; Spormann, Alfred M.; Logan, Bruce E. (2015). "Methanobacterium dominates biocathodic archaeal communities in methanogenic microbial electrolysis cells". ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering. 3 (7): 1668−1676. doi:10.1021/acssuschemeng.5b00367.

- ^ Siegert, Michael; Li, Xiu-Fen; Yates, Matthew D.; Logan, Bruce E. (2015). "The presence of hydrogenotrophic methanogens in the inoculum improves methane gas production in microbial electrolysis cells". Frontiers in Microbiology. 5: 778. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2014.00778. PMC 4295556. PMID 25642216.

- ^ Sato, Kozo; Kawaguchi, Hideo; Kobayashi, Hajime (2013). "Bio-electrochemical conversion of carbon dioxide to methane in geological storage reservoirs". Energy Conversion and Management. 66: 343. doi:10.1016/j.enconman.2012.12.008.

- ^ "BioProtein Production" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 May 2017. Retrieved 31 January 2018.

- ^ "Food made from natural gas will soon feed farm animals – and us". Archived from the original on 12 December 2019. Retrieved 31 January 2018.

- ^ "New venture selects Cargill's Tennessee site to produce Calysta FeedKind Protein". Archived from the original on 30 December 2019. Retrieved 31 January 2018.

- ^ "Assessment of environmental impact of FeedKind protein" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 August 2019. Retrieved 20 June 2017.

- ^ "Excess wind power is turned into green gas in Avedøre". Archived from the original on 2014-05-31. Retrieved 2014-05-30.

- ^ "Electrochaea". Archived from the original on 2014-01-12. Retrieved 2014-01-12.

- ^ Martin, Matthew R.; Fornero, Jeffrey J.; Stark, Rebecca; Mets, Laurens; Angenent, Largus T. (2013). "A Single-Culture Bioprocess of Methanothermobacter thermautotrophicus to Upgrade Digester Biogas by CO

2-to-CH

4 Conversion with H

2". Archaea. 2013: 157529. doi:10.1155/2013/157529. PMC 3806361. PMID 24194675. Article ID 157529. - ^ "Power-to-Gas Energy Storage - Technology Description". Electrochaea.com. Archived from the original on 2014-01-12. Retrieved 2014-01-12.

- ^ "Power-to-Gas plant for Delfzijl". Archived from the original on 2014-05-31. Retrieved 2014-05-30.

- ^ "Sunshine to Petrol". Sandia National Laboratories. United States Department of Energy (DOE). Retrieved 15 May 2015.

- ^ SNL: Sunshine to 가솔린 - 이산화탄소를 탄화수소 연료로 재활용

- ^ "Sandia and Sunshine-to-Petrol: Renewable Drop-in Transportation Fuels". Federal Business Opportunities. U.S. Federal Government. Oct 29, 2013. Retrieved 15 May 2015.

- ^ Biello, David (September 23, 2010). "Reverse Combustion: Can CO2 Be Turned Back into Fuel?". Scientific American - Energy & Sustainability. Archived from the original on 16 May 2015. Retrieved 17 May 2015.

- ^ Lavelle, Marianne (August 11, 2011). "Carbon Recycling: Mining the Air for Fuel". National Geographic - News. National Geographic Society. Archived from the original on 20 May 2015. Retrieved 19 May 2015.

- ^ "Bright Way to Convert Greenhouse Gas to Biofuel". Weizmann UK. Weizmann UK. Registered Charity No. 232666. 18 December 2012. Retrieved 19 May 2015.[영구 데드링크]

- ^ "CO

2 and H

2O Dissociation Process". NCF - Technology Process. New CO2 Fuels Ltd. Retrieved 19 May 2015. - ^ "Newsletter NewCO2Fuels, Issue 1" (PDF). September 2012.

- ^ "From challenge to opportunity New CO

2 Fuels: An Introduction..." (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2015-05-30. Retrieved 2015-05-30. - ^ "SOLAR-JET Project". SOLAR-JET. SOLAR-JET Project Office: ARTTIC. Archived from the original on 18 May 2015. Retrieved 15 May 2015.

- ^ "Sunlight to jet fuel". The ETH Zurich. Eidgenössische Technische Hochschule Zürich. Archived from the original on 10 September 2014. Retrieved 15 May 2015.

- ^ Alexander, Meg (May 1, 2014). ""Solar" jet fuel created from water and carbon dioxide". Gizmag. Gizmag. Archived from the original on 18 May 2015. Retrieved 15 May 2015.

- ^ "SOLARJET demonstrates full process for thermochemical production of renewable jet fuel from H2O & CO2". Green Car Congress. BioAge Group, LLC. 28 April 2015. Archived from the original on 18 May 2015. Retrieved 15 May 2015.

- ^ "Aldo Steinfeld - Solar Syngas". Solve For <X>. Google Inc.[영구 데드링크]

- ^ "Brewing fuels in a solar furnace" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2015-05-19. Retrieved 2015-05-30.

- ^ "Syntrolysis, Synthetic Fuels from Carbon Dioxide, Electricity and Steam" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-05-21. Retrieved 2015-05-30.

- ^ "Synthetic Fuel (syntrolysis)". Thoughtware.TV. Thoughtware.TV. June 17, 2008. Retrieved 20 May 2015.

- ^ Stoots, C.M.; O'Brien, J.T.; Hartvigsen, J. (2007). "Carbon Neutral Production of Syngas via High Temperature Electrolytic Reduction of Steam and CO

2" (PDF). ASME 2007 International Mechanical Engineering Congress and Exposition. 2007 ASME International Mechanical Engineering Congress and Exposition, November 11–15, 2007, Seattle, Washington, USA. Vol. 15: Sustainable Products and Processes. pp. 185–194. doi:10.1115/IMECE2007-43667. ISBN 978-0-7918-4309-3. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 21, 2015. Retrieved May 30, 2015. - ^ 핵수소 이니셔티브의 개요

- ^ 핵수소 생산기술

- ^ 웨이백 머신에 보관된 2015-05-30 합성 연료 생산을 위한 전기 분해

- ^ "The WindFuels Primer - Basic Explanation for the Non-scientist". Doty Energy. Doty Energy. Archived from the original on 16 May 2015. Retrieved 16 May 2015.

- ^ "Securing Our Energy Future by Efficiently Recycling CO

2 into Transportation Fuels" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2015-05-30. - ^ "The AFS Process - turning air into a sustainable fuel". Air Fuel Synthesis - Technical Review. Air Fuel Synthesis Limited. Archived from the original on 3 April 2015. Retrieved 19 May 2015.

- ^ 도입 사례: AFS 데모 유닛[영구 데드링크]

- ^ "Cars Fueled by Air?". PlanetForward.org. Planet Forward. Retrieved 20 May 2015.

- ^ Rapier, Robert (October 31, 2012). "Investors Beware of Fuel from Thin Air". Investing Daily. Archived from the original on 18 May 2015. Retrieved 17 May 2015.

- ^ Williams, K.R.; van Lookeren Campagne, N. Synthetic Fuels From Atmospheric Carbon Dioxide (PDF) (Report). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-03-04.

- ^ "Air Fuel Synthesis Limited". www.thegazette.co.uk. The Gazette. Retrieved 19 October 2018.

- ^ "BGU Researchers invent Green Alternative to Crude Oil". Ben-Gurion University of the Negev. Ben-Gurion University of the Negev. 13 November 2013. Retrieved 17 May 2015.

- ^ "Recent Success Story: Converting carbon dioxide, a damaging greenhouse gas, into fuel that may be used for transportation". I-SAEF. Israel Strategic Alternative Energy Foundation. Retrieved 15 May 2015.

- ^ "BGU Researchers Develop New Type of Crude Oil Using Carbon Dioxide and Hydrogen". American Associates (Ben-Gurion University of the Negev). American Associates (AABGU). Archived from the original on 18 May 2015. Retrieved 15 May 2015.

- ^ "BGU researchers developing more efficient process for hydrogenation of CO2 to synthetic crude". Green Car Congress. BioAge Group, LLC. 21 November 2013. Archived from the original on 4 August 2015. Retrieved 15 May 2015.

- ^ "Fuel of the future: Research facility in Dresden produces first batch of Audi e-diesel". Audi MediaServices - Press release. Ingolstadt/Berlin: AUDI AG. 2015-04-21. Archived from the original on 19 May 2015. Retrieved 23 May 2015.

- ^ Rapier, Robert. "Is Audi's Carbon-Neutral Diesel a Game-Changer?". Energy Trends Insider. Energy Trends Insider. Archived from the original on 18 May 2015. Retrieved 15 May 2015.

- ^ Novella, Steven (28 April 2015). "Apr 28 2015 Audi's E-Diesel". The NeuroLogicaBlog - Technology. Steven Novella, MD. Archived from the original on 30 May 2015. Retrieved 24 May 2015.

- ^ "How the United States Navy Plans to Turn Seawater into Jet Fuel". Alternative Energy. altenergy.org. Retrieved 8 May 2015.

- ^ "Patent: US 20140238869 A1". Google Patents. Archived from the original on 18 May 2015. Retrieved 8 May 2015.

- ^ 세계 바다의 총 탄소 함량은 약 38,000 GtC입니다.이 탄소의 95% 녹아 있는 중탄산 이온(HCO3 −)의 형태에 있다.클라인, 윌리엄(1992년).경제학 지구 온난화.워싱턴 DC:국제 경제 연구소.바다의 녹아 있는 중탄산염 소다와 탄산 본질적으로 이 종들 중 기체 이산화 탄소, 다음 방정식에서 표시와 함께 그 합은 그 세계의 바다의 총 이산화 탄소 농도[이산화 탄소]T을 나타내는 이산화 탄소이다.Σ[이산화 탄소]T=[이산화 탄소(g)]l+는 경우HCO3 −]+[CO3 2−][검증 필요한]

추가 정보

- Götz, Manuel; Lefebvre, Jonathan; Mörs, Friedemann; McDaniel Koch, Amy; Graf, Frank; Bajohr, Siegfried; Reimert, Rainer; Kolb, Thomas (2016). "Renewable Power-to-Gas: A technological and economic review". Renewable Energy. 85: 1371–1390. doi:10.1016/j.renene.2015.07.066.

- 메지앙 부델랄"Le Power-to-Gas, Stockage de Electricité d'original renouvelable" 192쪽프랑스어만.에디터:듀노드, 2016년 6월

- 메지앙 부델랄"Power-to-Gas.에너지 전환을 위한 재생 가능한 수소 경제." 212페이지.영문판편집자: de Gruyter, 2018년 2월

외부 링크

- 에너지기술연구소 3분 설명 동영상(2016년)

- ZSW(Zentrum für Sonnenenergie-und Wasserstoff-Forschung) 바덴뷔르템베르크

- 스메들리, 팀에너지 대 가스 저장 장치는 화석 연료 사용을 대체하는데 도움이 될 수 있습니다, The Guardian, 2014년 7월 4일.2014년 7월 21일 취득.

- 취리히 베르데홀즐리 시제품 설치 프레젠테이션(독일어).