뇌의 언어 처리

Language processing in the brain

언어 처리란 인간이 단어를 사용하여 사상과 감정을 전달하는 방식, 그리고 그러한 의사소통이 어떻게 처리되고 이해되는지를 말한다. 언어 처리는 인간의 가장 가까운 영장류 친척들에게도 같은 문법적 이해나 체계성을 가지고 생산되지 않는 독특한 인간의 능력이라고 여겨진다.[1]

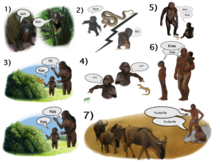

20세기 내내 뇌에서 언어 처리의 지배적인 모델은[2] 게슈윈드-리히테임-베르니케 모델이었는데, 주로 뇌 손상 환자의 분석에 기초하고 있다. 그러나 원숭이와 인간의 뇌에 대한 정맥내 전기생리학 기록의 향상과 더불어 fMRI, PET, MEG, EEG 등 비침습적 기법도 개선되어 이중 청각 경로가[3][4] 밝혀지고 2-스트림 모델이 개발되었다. 이 모델에 따라 청각 피질을 전두엽에 연결하는 두 가지 경로가 있는데, 각 경로는 서로 다른 언어적 역할을 고려한다. 청각적 복측 흐름 경로는 소리 인식을 담당하며, 따라서 청각적 '무엇' 경로로 알려져 있다. 인간과 인간이 아닌 영장류 모두의 청각 등줄기는 소리 국산화 작용을 하며, 따라서 청각 '어디' 경로로 알려져 있다. 인간에게 있어서 이 길(특히 좌뇌에서)은 음성 생산, 음성 반복, 입술 읽기, 음운론적 작업 기억과 장기 기억에도 책임이 있다. 언어 진화의 '어디에서 무엇으로' 모델에 따라,[5][6] ADS가 이처럼 광범위한 기능으로 특징지어지는 이유는 각각 언어 진화의 다른 단계를 나타내기 때문이다.

두 개의 흐름의 분할은 먼저 청각 신경에서 발생하며, 뇌관의 전측 가지(전측)가 전측 달팽이핵으로 들어가 청각적 복측 흐름을 일으킨다. 후부는 등지핵과 후발성 달팽이핵으로 들어가 청각 등지류를 발생시킨다.[7]: 8

언어 처리는 수화 언어 또는 서면 컨텐츠와 관련해서도 발생할 수 있다.

초기 신경언어학 모델

20세기 내내, 우리의 두뇌 언어 처리 지식은 베르니케-리히테임-게슈윈드 모델에 의해 지배되었다.[8][2][9] 베르니케-리히테임-게슈윈드 모델은 주로 다양한 언어 관련 장애를 가지고 있는 것으로 보고된 뇌 손상 개인에 대한 연구에 기초하고 있다. 이 모델에 따라 단어들은 왼쪽 임시변통 접합부에 위치한 전문 단어 접수 센터(Wernicke's 영역)를 통해 인식된다. 그 후 이 지역은 좌측 하전두회(Broca's area)에 위치한 단어 생산 센터(Broca's area)에 투영된다. 거의 모든 언어 입력은 베르니케 지역을 통해 유입되고 모든 언어 출력은 브로카 지역을 통해 유입되는 것으로 생각되었기 때문에, 각 지역의 기본 특성을 파악하는 것이 극도로 어려워졌다. 인간의 언어에 대한 베르니케와 브로카 지역의 기여에 대한 이러한 명확한 정의의 결여는 다른 영장류에서 그들의 동음이의어를 식별하는 것을 극도로 어렵게 만들었다.[10] 그러나 fMRI의 출현과 병변 매핑에 대한 그것의 적용으로, 이 모델은 증상과 병변 사이의 잘못된 상관관계에 기초하고 있는 것으로 나타났다.[11][12][13][14][15][16][17] 그러한 영향력 있고 지배적인 모델의 반박은 뇌에서 언어 처리의 새로운 모델에 대한 문을 열었다.

현재 신경언어학 모델

해부학

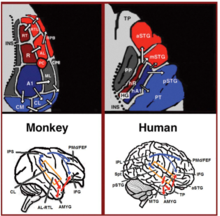

지난 20년 동안, 영장류에서 소리의 신경 처리에 대한 우리의 이해에 상당한 진전이 있었다. 처음에는 원숭이의[18][19] 청각 피질에서 신경 활동을 기록하고 나중에 조직학적 얼룩과[20][21][22] fMRI 스캔 연구를 통해 정교하게 기술하여,[23] 1차 청각 피질에서 3개의 청각장을 확인하였고, 9개의 연관 청각장이 그들을 둘러싸는 것을 보여주었다(그림 1 상단 왼쪽). 해부학적 추적 및 병변 연구에서는 전방 1차 청각장(areas R-RT)이 전방 1차 청각장(areas AL-RTL)에 투영되고 후방 1차 청각장(areas AL-RTL)이 후측 연관 청각장에 투영되는 전후 청각장(areas A1) 사이에 분리가 추가적으로 나타났다. 필드(areas CL-CM).[20][24][25][26] 최근 인간과 원숭이 청각장 사이의 동질감을 나타내는 증거가 축적되었다. 인간에게 조직학적 오염 물질 연구 Heschl의 gyrus,[27][28]의 일차 청각 영역과와 원숭이 일차 청각 분야의 음위상 조직에 비유하며 고해상 fMRI로 인간의 일차 청각 분야의 음위상 조직 지도가 가능, 상동이었다,에 두개의 분리된 청각 분야를 밝혔다.betw Iago인간 전방 1차 청각장 및 원숭이 영역 R(인간에서 영역 hR로 표시됨)과 인간 후방 1차 청각장 및 원숭이 영역 A1(인간에서 영역 hA1로 표시됨)[29][30][31][32][33]이다. 인간의 청각피질에서 나온 정맥내 녹음은 원숭이의 청각피질과 유사한 연결 패턴을 더 잘 보여주었다. Recording from the surface of the auditory cortex (supra-temporal plane) reported that the anterior Heschl's gyrus (area hR) projects primarily to the middle-anterior superior temporal gyrus (mSTG-aSTG) and the posterior Heschl's gyrus (area hA1) projects primarily to the posterior superior temporal gyrus (pSTG) and the planum temporale (area PT; 그림 1 오른쪽).[34][35] 영역 hR에서 aSTG로, hA1에서 pSTG로의 연결과 일치하여, 영역 hR과 aSTG에서 양방향 활성화가 감소했지만 mSTG-PSTG에서 활성화가 절약된 것으로 나타난 손상된 음 인식(청각 혈관) 환자의 fMRI 연구가 있다.[36] 이러한 연결 패턴은 청각 피질의 측면 표면에서 활성화가 기록되고 소리를 듣는 동안 pSTG와 mSTG-aSTG의 동시 비 겹침 활성화 클러스터가 보고된 연구에 의해서도 확증된다.[37]

청각 피질에 대한 하류에서, 원숭이들의 해부학적 추적 연구는 전상 연관 청각장(ARE-RTL)에서 하전두회(IFG)[38][39]와 편도체 내 복측 전측 및 전측 피질까지 투영을 묘사했다.[40] 마카크 원숭이의 피질적 기록과 기능적 영상 연구는 음향 정보가 전방 청각 피질에서 측두극(TP)으로 그리고 그 다음 IFG로 흐른다는 것을 보여줌으로써 이 처리 흐름에 대해 더욱 상세히 설명하였다.[41][42][43][44][45][46] 이 경로를 일반적으로 청각적 복측 스트림(AVS; 그림 1, 왼쪽 아래 화살표)이라고 한다. 전방의 청각장과 대조적으로, 추적 연구는 후방의 청각장(areas CL-CM)이 주로 등측 전방 및 전전두 피질(IFG에서 일부 투영이 종료되지만)에 대한 것으로 보고하였다.[47][39] 원숭이에 대한 피질 기록과 해부학적 추적 연구는 또한 이 처리 스트림이 후청장에서 정맥내 설커스(IPS)의 중계소를 통해 전두엽으로 흐른다는 증거를 제공했다.[48][49][50][51][52][53] 이 경로를 일반적으로 청각 등축 스트림(ADS; 그림 1, 왼쪽 아래 파란색 화살표)이라고 한다. 인간과 원숭이의 의사소통에 관련된 백질 경로를 확산 텐서 영상 기법과 비교한 결과 두 종(몽키,[52] 인간[54][55][56][57][58][59])에서 AVS와 ADS가 유사한 연관성을 나타낸다. In humans, the pSTG was shown to project to the parietal lobe (sylvian parietal-temporal junction-inferior parietal lobule; Spt-IPL), and from there to dorsolateral prefrontal and premotor cortices (Figure 1, bottom right-blue arrows), and the aSTG was shown to project to the anterior temporal lobe (middle temporal gyrus-temporal pole; MTG-TP) and 여기에서 IFG까지(그림 1 오른쪽-빨간색 하단 화살표).

청각적 복측

청각 복측 스트림(AVS)은 청각 피질을 중간 측두회 및 측두극과 연결하며, 이는 다시 하전두회(하전두회)와 연결된다. 이 경로는 소리 인식을 담당하며, 따라서 청각적 '무엇' 경로로 알려져 있다. AVS의 기능은 다음과 같다.

음향인식

누적 수렴 증거는 AVS가 청각 물체를 인식하는 데 관여한다는 것을 나타낸다. 일차 청각 피질 수준에서 원숭이의 녹음은 영역 A1보다 영역 R에서 학습된 멜로디 시퀀스에 대해 선택적으로 선택된 뉴런의 비율이 더 높았으며,[60] 인간에 대한 연구는 후측 헤슐의 회음부(면적 hR)에서 후측 헤슐의 회음부(면적 HA1)보다 청각 음절의 선택성이 더 높은 것으로 나타났다.[61] 다운스트림 연상 청각장에서는 원숭이와 인간의 양쪽 연구결과에 따르면 전 후청장(원숭이의 그림 1 영역 PC와 인간의 mSTG)의 경계가 청각 물체의 인식에 필요한 피치 속성을 처리한다고 한다.[18] 원숭이의 앞쪽 청각장 또한 정맥내 녹음으로 특정 원추형 발성을 위한 선택성으로 입증되었다.[41][19][62] 기능적 영상화[63][42][43] 원 fMRI 원숭이 연구는 개별 음성을 인식하는 데 있어 aSTG의 역할을 더욱 입증했다.[42] 음성 인식의 mSTG-aSTG의 역할은 이 지역에서 활동 배경 noise,[64][65]에서 청각적 개체의 격리와 구어 words,[66][67][68][69][70][71][72]voices,[73]melodies,[74][75]환경 sounds,[76][77][78]과non-s의 인식과 상관 기능적 영상 연구를 통해 입증되었다.peech 의사 소통 소리를 낸다.[79] fMRI 연구의[80] 메타 분석은 왼쪽 mSTG와 aSTG 사이의 기능적 괴리를 추가로 입증했으며, 전자는 짧은 음성 단위(phonemes)를 처리하고 후자는 긴 단위(예: 단어, 환경 소리)를 처리했다. 왼쪽 pSTG와 aSTG에서 직접 신경 활동을 기록한 연구는 환자가 생소한 외국어보다 모국어로 말을 들을 때 pSTG가 아닌 aSTG가 더 활발하다고 보고했다.[81] 일관되게, 이 환자의 aSTG에 대한 전기 자극은 언어 지각의[81] 손상을 초래했다(유사한 결과는 또한[82][83] 참조). 오른쪽과 왼쪽의 정맥내 녹음은 또한 음성이 음악에 대해 횡방향으로 처리된다는 것을 증명했다.[81] 구어 및 환경 소리를 들을 때 양쪽 반구 영역 hR과 aSTG의 활성화가 감소하여 뇌계 손상으로 인해 음향 인식(청각 장애)이 손상된 환자를 대상으로 한 fMRI 연구도 나타났다.[36] 작동 메모리에서 학습된 소리를 유지하면서 원숭이의 전방 청각 피질에서 녹음하고 [46]이 영역에 유도된 병변이 작동 메모리 호출에 미치는 쇠약해지는 효과는 AVS가 작동 메모리에서 인지된 청각 물체를 유지하는데 더욱 관련이 있다.[84][85][86] 인간에서도 영역 mSTG-aSTG는 MEG 및 fMRI와 함께 청취 음절 리허설 중에 활성 상태로 보고되었다. 후자의 연구는 AVS에서의 작동 메모리가 구어의 음향 특성을 위한 것이며 내부 음성을 매개하는 ADS의 작동 메모리와 독립적이라는 것을 더욱 입증했다.[87] 원숭이에 대한 작업 기억 연구들은 또한 원숭이의 경우 인간과 대조적으로 AVS가 지배적인 작업 기억 저장소라는 것을 시사한다.[89]

aSTG의 하류인 인간에서 MTG와 TP는 의미적 어휘를 구성하는 것으로 생각되는데, 이는 의미적 관계에 기초하여 상호 연결된 시청각 표현들의 장기 기억 저장고다. (이 주제에 대한 논의에 의한[3][4] 검토도 참조) MTG-TP의 이러한 역할에 대한 주요 증거는 이 지역에 피해를 입은 환자(예: 의미성 치매 또는 헤르페스 단순성 바이러스 뇌염 환자)가 시각 및 청각 사물을 설명할 수 있는 장애가 있고 사물을 명명할 때 의미 오류를 범하는 경향(즉, 의미성 파라파시아)을 가지고 보고된다는[90][91] 것이다. 시멘틱 파라파시아는 좌측 MTG-TP 손상이[14][92] 있는 실어증 환자에 의해서도 표현되었으며, 이 부위에 전기 자극을 가한 후 실어증이 아닌 환자에게서 발생하는 것으로 나타났다.[93][83] 또는 기초적인 백질 경로[94]. fMRI 문헌의 두 메타 분석은 또한 언어와 텍스트의 의미 분석 동안 전방의 MTG와 TP가 일관되게 활동한다는 것을 보고했고,[66][95] 이해할 수 있는 문장의 이해와 함께 MTG에서 상관관계가 있는 신경 방전 연구도 보고했다.[96]

문장 이해

소리로부터 의미를 추출하는 것 외에도, AVS의 MTG-TP 영역은 문장 이해에 역할을 하는 것으로 보이며, 아마도 개념들을 함께 융합함으로써(예를 들어 '파란색'과 '셔츠'를 병합하여 '파란색 셔츠'의 개념을 만들어 내는 것) 가능하다. 문장으로부터 의미를 추출하는 MTG의 역할은 적절한 문장이 단어의 목록, 외국어 또는 난센스 언어의 문장, 스크램블 문장, 의미 또는 통사적 위반이 있는 문장 및 문장 비슷한 문장과 대조될 때 전방의 MTG에서 더 강력한 활성화가 보고되는 기능적 이미지 연구에서 입증되었다. 일련의 환경적 [97][98][99][100][101][102][103][104]소리들 참가자들에게 앞의 MTG에서 각 문장이 포함하는 의미론적 및 통사적 내용의 양과 함께 더 상관관계가 있는 이야기를 읽도록 지시된 한 fMRI 연구[105]. 건강한 상태 참여자와 MTG-TP 손상을 가진 환자들에서 통사적 위반 없이로 문장을 읽는 피질 활동을 대조하였다 뇌 전도 study[106]은 MTG-TP 양쪽에서 구문 해석(ELAN 구성 요소)의 자동(규칙 기반)무대에 남아 있고 왼쪽 MTG-TP 또한에 연루된 참여하다고 결론지었다. 는 라terr 제어된 구문 분석 단계(P600 구성요소). MTG-TP 부위가 손상된 환자도 문장 이해 능력이 저하된 것으로 보고되었다.[14][107][108] 이 항목에 대한 자세한 내용은 검토를[109] 참조하십시오.

다변측정학

는 음성 인식 단지 왼쪽 반구에서 일어나는 것을 분명하게 보여 주는 Wernicke-Lichtheim-Geschwind 모델에게도 모순에 각 hemisphere[96]에서 일방적인 반구 마취(즉 세계반 도핑 기구 procedure[110])또는intra-cortical 녹화를 통하여 오른쪽 또는 왼쪽 반구의 격리의 속성을 연구 ev을 제공했다.idence 그음향 인식은 쌍방적으로 처리된다. 게다가, 분리된 우뇌와 좌뇌를 보이는 환자라고 지시한 연구 쓴 글 오른쪽 또는 왼쪽 hemifields에 제출한 구어체 말과 일치하는 것은 규모 면에서 왼쪽 hemisphere[111]에 잘 어울리는 신발 오른쪽 반구에(오른쪽 반구 어휘는 어의와 동등한 것이었다 어휘 보도했다(즉, 분할 뇌 환자).y의 건강한 11살 아이). 이러한 양쪽의 소리 인식은 청각 피질에 대한 일방적 병변이 청각 이해(즉, 청각 장애)에 대한 결손(즉, 청각 장애)을 초래하는 경우는 드물지만, 나머지 반구에 대한 두 번째 병변(수년 후에 발생할 수 있음)[112][113]은 거의 없다는 발견과도 일치한다. 마지막으로, 앞에서 언급한 바와 같이, 청각 장애 환자의 fMRI 스캔은 전방 청각 피질에서 양쪽의 활성화를 감소시켰으며,[36] 양쪽 반구의 이러한 부위에 대한 양쪽 전기 자극은 언어 인식의 저하로 나타났다.[81]

청각 등수류

청각 등축 흐름은 청각 피질을 두정엽과 연결하고, 두정엽은 다시 하전두회(하전두회)와 연결한다. 인간과 인간이 아닌 영장류 둘 다에서 청각 등줄기는 소리 국소화를 담당하며, 따라서 청각 '어디' 경로로 알려져 있다. 인간에게 있어서 이 길(특히 좌뇌에서)은 음성 생산, 음성 반복, 입술 읽기, 음운론적 작업 기억과 장기 기억에도 책임이 있다.

스피치 프로덕션

오늘날 인간에 대한 연구는 음성 생산, 특히 사물의 이름의 발성 표현에서 ADS의 역할을 입증했다. 예를 들어 왼쪽 pSTG와 IPL에서 아구체 섬유가 직접 자극된[94] 일련의 연구에서 물체 이름 지정 작업 중 오류가 발생했고 왼쪽 IFG의 간섭으로 인해 언어 구속이 발생하였다. 건강한 참가자들의 pSTG과 IFG에 자기 간섭은 또한 언론 오류와 연설 체포를 제작한 respectively[114][115]어느 연구 결과는 왼쪽 IPL의 전기 자극들은 IFG 자극들이 무의식적으로 입술을 움직이다고 환자를 일으키지 않았다면 사용했다 믿게 하여 보도했다.[116] 그 ADS의 개체의 이름을 분명하게 말하고의 과정에 대한 afferents의 대동맥 판 협착증의 의미적 사전을 대접을,intra-cortical 녹화 조사 결과 환자들 pictures[117]Intra-cortical에 물건들의 이름을 활성화의 선행 MTG 전에 활성화는 Spt-IPL 지역에서 보고된 의존할 수 있다. 감전 사고가 나다또한 3차 자극 연구에서는 후방 MTG에 대한 전기적 간섭이 손상된 물체 이름과[118][82] 상관관계가 있다고 보고하였다.

성대모사

비록 건전한 인식은 주로 AVS에 기인하지만, ADS는 음성 인식의 몇 가지 측면과 연관되어 보인다. 예를 들어, 음소에 대한 청각적 지각과 근접하게 일치하는 소리를 비교한 fMRI 연구[119](Turkeltaub and Coslett, 2010)의 메타 분석에서, 저자들은 음소에 대한 관심이 pSTG-PS 영역의 강한 활성화와 상관관계가 있다고 결론지었다. 참가자들에게 음절을 식별하도록 지시받은 정맥내 기록 연구도 각 음절의 청력과 PSTG의 자체 활성화 패턴과 상관관계가 있었다.[120] 음성 인식과 생산에 대한 ADS의 참여는 음성 인식을 명시적이거나 은밀한 음성 생산과 대조한 몇몇 선구적인 기능 이미지 연구에서 더욱 조명되었다.[121][122][123] 이러한 연구는 PSTS가 언어의 인식 동안만 활성화되는 반면, 영역 Spt는 언어의 인식과 생산 모두에서 활성화된다는 것을 보여주었다. 저자들은 PSTS가 청각 입력을 발현 운동으로 변환하는 영역 Spt에 프로젝트를 진행한다고 결론지었다.[124][125] 참가자들의 측두엽과 두정엽이 전기적으로 자극을 받은 연구에서도 비슷한 결과가 나왔다. 본 연구는 PSTG 부위를 전기적으로 자극하면 문장 이해에 방해가 되고 IPL의 자극은 사물의 이름을 발성하는 능력에 방해가 된다고 보고했다.[83] 저자들은 또한 영역 Spt와 하한 IPL에서의 자극이 객체 이름 지정과 음성 분석 작업 모두에서 간섭을 유발했다고 보고했다. 음성 반복에서 ADS의 역할은 음성 반복 작업 중 ADS 영역에 대한 지역적 활성화를 수행한 다른 기능적 영상 연구 결과와도 일치한다.[126][127][128] 대부분의 측두엽, 두정엽, 전두엽 전반에 걸쳐 활동을 기록한 정맥내 기록 연구에서도 음성 반복이 음성 인식과 대조될 때 PSTG, Spt, IPL 및 IFG에서 활성화가 보고되었다.[129] 신경 심리 연구들도 연설을 가진 개인 반복 적자지만 보존된 청각적 이해력은 Spt-IPL area[130][131][132][133][134][135][136]에 제한적 손상 또는 이 지역에서 우러나오돌출부 손상으로 고통 그리고 S. 전면 lobe[137][138][139][140]을 목표로 고통 받(즉, 전도성 실어)을 발견했다Tudies 또한 일시적인 연설 repetitio 보도했다.같은 부위에 직접 자극한 후 환자의 결손은 없다.[11][141][142] ADS에서 언어 반복의 목적에 대한 통찰은 외국어의 어휘 학습과 헛된 단어를 반복하는 능력을 연관시킨 어린이의 종적 연구에 의해 제공된다.[143][144]

음성 모니터링

ADS는 말을 반복하고 생산하는 것 외에도 음성 출력의 품질을 감시하는 역할을 하는 것으로 보인다. 신경학적 증거는 ADS가 IFG에서 PSTG까지 내림차 연결부를 갖추고 있으며, 이 연결은 성악기(입, 혀, 성주름)에서 운동 활동(즉, 골수 방전)에 대한 정보를 전달한다. 이 피드백은 음성 제작 중 인지된 소리를 자체 제작으로 표시하며, 인식된 통화와 방출된 통화 사이의 유사성을 높이기 위해 발성 장치를 조정하는 데 사용할 수 있다. 그 IFG에서 pSTG는 연결의 증거는 전기 수술 수술 중에 및 활성화의 pSTG-pSTS-Spt으로 확산된 것에는 신속하고 repea에, 두정엽 또는 시간 전두엽 손상을 입은 채 실어증의 환자들의 능력을 비교했다 Astudy[146]region[145]을 보고했다 IFG을 자극했다 연구들에 의해 제공 받았다.tedly 예술일련의 음절들을 고정한 결과 전두엽에 대한 손상이 동일한 음절 현("Bababa")과 비식별적인 음절 현("Badaga")의 발음을 방해하는 반면, 측두엽 또는 두정엽 손상이 있는 환자는 비식별적인 음절 현을 발현할 때만 장애를 보였다. 측두엽과 두정엽 손상이 있는 환자들은 첫 번째 과제에서 음절현상을 반복할 수 있었기 때문에 음성 인식과 생산성이 비교적 보존된 것으로 보이며, 따라서 두 번째 과제에서의 적자는 모니터링의 장애로 인한 것이다. 한 fMRI 연구는 유출된 통화를 모니터링하는 과정에서 하강하는 ADS 연결의 역할을 입증하면서 참가자들에게 정상적인 조건이나 자신의 음성의 변형된 버전(지연된 첫 번째 형태)을 들을 때 발언할 것을 지시했고, 왜곡된 버전의 자신의 음성을 들으면 PSTG의 활성화가 증가한다고 보고했다.[147] ADS가 모방 중에 모터 피드백을 용이하게 한다는 것을 추가로 입증하는 것은 음성 인식과 반복을 대조한 정맥내 녹음 연구다.[129] 저자들은 IPL과 IFG의 활성화 외에도 음성 인식 시보다 PSTG에서 음성 반복이 더 강하게 활성화되는 특징이 있다고 보고했다.

입술 움직임과 음소의 통합

비록 건전한 인식은 주로 AVS에 기인하지만, ADS는 음성 인식의 몇 가지 측면과 연관되어 보인다. 예를 들어, 음소에 대한 청각적 인식이 밀접하게 일치하는 소리와 대비되고, 필요한 관심 수준에 대한 연구가 평가된 fMRI 연구의[119] 메타 분석에서, 저자들은 음소에 대한 관심이 pSTG-psTS 영역의 강한 활성화와 상관관계가 있다고 결론지었다. 참가자들에게 음절을 식별하도록 지시받은 정맥내 기록 연구도 각 음절의 청력과 PSTG의 자체 활성화 패턴과 상관관계가 있었다.[148] 음소를 구별하는 데 있어서 ADS의 역할과 일치하여,[119] 연구는 음소의 통합과 그에 상응하는 입술 움직임(즉, 시각)을 ADS의 pSTS로 돌렸다. 예를 들어, fMRI 연구는[149] pSTS에서 맥거크 환상(viseme "ga"를 보면서 음절 "ba"를 듣는 경우 음절 "da"의 인식으로 귀결된다. 또 다른 연구는 이 영역의 처리를 방해하기 위해 자기 자극을 사용하는 것이 맥거크 착시 현상을 더욱 교란시킨다는 것을 발견했다.[150] 언어의 시청각적 통합과 PSTS의 연관성은 참가자들에게 다양한 품질의 얼굴 사진과 구어체 사진을 제공하는 연구에서도 입증되었다. 이 연구는 PSTS가 얼굴과 구어의 명확성을 결합하여 증가시키기 위해 선택한다고 보고했다.[151] 시청각언어에 대한 인식과 시청각비언어(공구의 그림과 소리)를 대조한 fMRI 연구에[152] 의해 확증 증거가 제공되고 있다. 이 연구는 PSTS에서 음성 선택 컴파트먼트가 검출되었다고 보고했다. 또한, 일관되지 않은 시청각 언어와 일치하지 않는 언어(정면 사진)를[153] 대조한 fMRI 연구는 pSTS 활성화를 보고했다. 음소-시각 통합에서 PSTS와 ADS의 역할에 관한 추가적인 수렴 증거를 제시하는 검토는 다음을 참조하십시오.[154]

음운론적 장기 기억력

증가하는 증거의 단체는 인간이 AVS의 MTG-TP(즉, 의미 어휘론)에 위치한 단어 의미에 대한 장기 저장소를 가지고 있을 뿐만 아니라, ADS의 Spt-IPL 영역(즉, 음운론 어휘론)에 위치한 물체의 이름에 대한 장기 저장소를 가지고 있다는 것을 나타낸다. 예를 들어, AVS 손상(MTG 손상) 또는 IPL 손상(IPL 손상) 환자를 검사한 연구에서[155][156] MTG 손상이 개인을 잘못 식별하는 결과를 초래한다고 보고했다(예: "고트"를 의미론적 파라파시아의 예라고 부른다) 반대로 IPL 손상은 개인이 대상을 정확하게 식별하지만 그 이름을 잘못 발음하는 결과를 낳는다(예: 음소성 파라파시아의 예인 "고트" 대신 "고프"라고 말하는 것). 의미론적 파라파시아 오류는 AVS(Mortical Electrical Stimulation, MTG)를 받은 환자에서도 보고되었으며, 음소성 파라파시아 오류는 ADS(pSTG, Spt, IPL)를 받은 환자에서도 보고되었다.[83][157][94] 객체 명명에서 ADS의 역할을 추가로 지원하는 것은 학습 중과 객체 이름 회수 중에 IPL에서 지역화된 활동을 하는 MEG 연구다.[158] 참가자가 물체에 대한 질문에 답하는 동안 IPL에 자기 간섭을 유발한 연구는 참가자가 물체의 특성이나 지각 속성에 관한 질문에 답할 수 있지만, 그 단어가 두 음절 또는 세 음절을 포함하고 있는지를 질문했을 때 손상되었다고 보고하였다.[159] 또한 한 MEG 연구는 IPL 활성화의 변화와 아노미아니아(물체의 이름을 붙이는 능력 장애로 특징지어지는 장애)로부터의 회복과 관련이 있다.[160] 왜냐하면 증거 언어 구사자들 중에서 같은 말 점유율의 다른 음운적 표시는 같은 의미 representation,[163]톤을 보여 주또한 그 IPL의 단어의 발음 부호화의 역할 연구 결과가, monolinguals에 비해 언어 구사자들은 IPL에서 더 큰 피질 밀도 하지 말고, 그 MTG.[161][162]었다고 지원인상 나는IPL의 n 밀도는 음운론 어휘소의 존재를 확인한다. 2개 국어의 의미 어휘소는 단일 언어의 의미 어휘소와 유사할 것으로 예상되는 반면, 음운론 어휘는 2배 크기여야 한다. 이러한 발견과 일관되게, 단일 언어의 IPL에서의 피질 밀도는 어휘 크기와도 상관관계가 있다.[164][165] 특히, 객체 명명 작업에서 AVS와 ADS의 기능적 분리는 의미적 오류가 MTG 손상과 상관관계가 있음을 보여주는 판독 연구의 누적된 증거와 IPL 손상에 따른 음소성 오류에 의해 뒷받침된다. 이러한 연관성을 바탕으로 텍스트의 의미분석을 하한-임시교 및 MTG와 연계하고, 텍스트의 음운학적 분석을 pSTG-Spt-IPL과[166][167][168] 연계시켰다.

음운학적 작용기억

작업기억은 종종 언어에 사용되는 장기기억에 저장된 표현(phonological 표현)의 일시적 활성화로 취급된다. 작업 메모리와 언어 사이의 이러한 자원 공유는 리허설 중에 말하는 것이 작업 메모리에서 회수할 수 있는 항목 수의 현저한 감소를 초래한다는 것을[169][170] 발견함으로써 명백하다. 작동 기억력에 음운론적 어휘의 관여는 음운학적으로 다른 단어들의 목록(음운학적 유사성 효과)보다 최근에 학습된 음운학적으로 유사한 단어들의 리스트에서 단어를 떠올릴 때 더 많은 오류를 범하려는 개인들의 경향에서도 증명된다.[169] 또한 연구 결과, 독서 중 발생한 언어 오류는 최근에 학습된 음성학적으로 유사한 단어를 작업 기억에서 회수하는 동안 발생한 언어 오류와 현저하게 유사하다는 것이 밝혀졌다.[171] IPL 손상을 가진 환자들은 또한 마지막으로 둘 다 말 산출 오류와 장애인 근무 memory[172][173][174][175]을 보여 주기 관측되고 있는 경치가 일시적으로 공중 충돌 방지 체계에서 음운 항의 활성화의 언어 작업 기억은 결과 최근 모델 mainta의 조합으로 작업 기억을 설명하는 호환된다.representatio iningns 장기 기억에서 일시적으로 표현을 활성화하는 것과 병행하여 주의 메커니즘에 있다.[170][176][177][178] 단어 목록 리허설에서 ADS의 역할이 문장 이해[179] 중에 이 경로가 활성화된 이유라는 주장이 제기되었다. 작동 기억에서 ADS의 역할에 대한 검토는 다음을 참조하십시오.[180]

언어의 진화

청각 등축 흐름은 또한 소리 국소화[181][182][183][184][185] 및 눈 움직임의 안내와 같은 비언어 관련 기능도 가지고 있다.[186][187] 최근의 연구들은 또한 간질 환자의 피질에서 기록된 한 연구에서[188] 새로운 스피커의 존재에 대해 PSTG가 선택적이라고 보고했기 때문에 가족/직원의 국산화에서 ADS의 역할을 나타낸다. 3기 태아에 대한 fMRI 연구는 또한 Spt 영역이 순수한 음색보다 여성 언어에 더 선택적이라는 것을 보여주었고, Spt의 하위 섹션은 생소한 여성 목소리와 대조적으로 어머니의 언어에 더 선택적이다.

왜 그렇게 많은 기능이 인간 ADS에 기인하는지는 현재 알 수 없다. 이러한 기능을 하나의 틀에서 통일하려는 시도는 언어 진화의[190][191] '어디에서 무엇으로' 모델에서 수행되었다. 이 모델에 따라 ADS의 각 기능은 언어 진화의 중간 단계가 다른 것을 나타낸다. 건전한 국산화 및 음성·청각 물체와의 건전한 위치 통합의 역할은 말의 기원이 산모와 자손의 연락통화(이별의 경우 위치보고에 사용되는 통화) 교환이라는 증거로 해석된다. 억양의 인식과 생산에서 ADS의 역할은 억양이 있는 연락 통화를 수정함으로써, 아마도 경보 연락 통화와 안전한 연락 통화를 구별하기 위해 연설이 시작되었음을 보여주는 증거로 해석된다. 물체의 이름(phonological long-memory)을 인코딩하는 데 있어서 ADS의 역할은 억양으로 통화를 수정하는 것에서 완전한 발성 제어로 점진적으로 이행하는 증거로 해석된다. 입술 움직임과 음소거의 통합과 언어 반복에서 ADS의 역할은 처음에는 부모의 발성을 흉내내면서, 유아들이 입 동작을 흉내내면서 구어들이 학습되었다는 증거로 해석된다. 음성학적 작동 기억장치에서 ADS의 역할은 모방을 통해 학습한 단어가 말을 하지 않아도 ADS에서 활성 상태를 유지했다는 증거로 해석된다. 이것은 발성 목록을 리허설할 수 있는 개인들로 하여금 여러 음절로 단어들을 만들 수 있게 했다. ADS의 추가 개발로 단어 목록을 리허설할 수 있었고, 이는 문장과의 의사소통을 위한 인프라 구조를 제공했다.

뇌 속의 수화

신경과학 연구는 뇌에서 수화가 어떻게 처리되는지에 대한 과학적인 이해를 제공했다. 세계에는 135개 이상의 이산 수화들이 있는데, 이것은 한 나라의 개별적인 지역에 의해 형성된 다른 억양을 사용하고 있다.[192]

신경과학자들은 병변 분석과 신경 이미지 생성에 의존함으로써, 그것이 구어든 수어든 간에, 인간의 뇌는 뇌의 어느 부분이 사용되고 있는지에 대해 유사한 방식으로 언어를 처리한다는 것을 발견했다. [192]병변 분석은 언어와 관련된 특정 뇌 부위의 손상 결과를 조사하는 데 이용되며, 신경 영상화는 언어 처리에 관여하는 부문을 탐구한다.[192]

브로카 영역이나 베르니케 영역의 손상은 수화가 지각되는 것에 영향을 미치지 않는다는 이전의 가설들이 만들어졌지만, 그렇지 않다. 연구에 따르면 이러한 영역에 대한 손상은 수화 오류가 있거나 반복되는 구어에서 유사한 것으로 나타났다. 두 가지 언어 [192]모두에서, 그들은 보통 예술을 다루는 우뇌보다는 좌뇌의 손상에 의해 영향을 받는다.

언어의 활용과 처리에는 분명한 패턴이 있다. 수화로, 수화를 처리하는 동안 브로카 영역은 활성화되며, 수화를 처리하는 동안 베르니케 영역은 구어와 유사한 영역을 사용한다.

두 반구의 편중화에 대한 다른 가설들이 있어 왔다. 특히, 우반구는 언어의 전반적인 의사소통에 기여하는 반면, 좌반구는 국지적으로 언어를 생성하는데 우세할 것으로 생각되었다.[193] 실어증 연구를 통해, RHD 서명자들은 표지의 공간적 부분을 유지하는 데 문제가 있는 것으로 밝혀져 다른 곳과 적절하게 의사소통하는데 필요한 유사한 표지를 혼동하고 있다.[193] 반면 LHD 서명자들은 청각 환자와 비슷한 결과를 보였다. 게다가, 다른 연구들은 수화가 양자간에 존재하지만 결론에 도달하기 위해서는 연구를 계속해야 한다고 강조해왔다.[193]

뇌에 글쓰기

독서와 글쓰기의 신경학에 관한 비교적 작은 연구기관이 있다.[194] 수행된 대부분의 연구들은 작문이나 철자보다는 독서를 다루고 있으며, 두 종류의 연구 중 대부분은 오로지 영어에만 초점을 맞추고 있다.[195] 영어 맞춤법은 라틴어 대본을 사용하는 다른 언어에 비해 투명성이 떨어진다.[194] 일부 연구는 영어의 철자법에 초점을 맞추고 대본에서 발견된 몇 개의 로그 문자를 생략하는 것도 또 다른 어려움이다.[194]

스펠링 측면에서 영어단어는 정규, 불규칙, 그리고 "귀여운 단어" 또는 "비어(nonwords)"의 세 가지 범주로 나눌 수 있다. 정규어는 철자법에서 그래핀과 음운 사이에 규칙적인 일대일 서신이 있는 낱말이다. 불규칙적인 단어는 그러한 서신이 존재하지 않는 단어들이다. 비어(nonwords)는 정규어의 예상 맞춤법을 보여주지만 의미를 담고 있지 않은 단어(nonce words)나 의성어(onomatopoeia)와 같이 말이다.[194]

영어 읽기 및 철자에 대한 인지 및 신경학적 연구에서의 문제는 단일 경로 또는 이중 경로 모델이 어떻게 문맹 화자들이 맞춤법 정확성의 허용된 표준에 따라 영어 단어의 세 가지 범주 모두를 읽고 쓸 수 있는지를 가장 잘 기술하는지 여부다. 단일 경로 모델은 어휘 메모리가 단일 프로세스에서 검색을 위한 모든 단어의 철자를 저장하는 데 사용된다고 가정한다. 이중 루트 모델은 불규칙적이고 고주파 정규 단어를 처리하기 위해 어휘 메모리를 사용하는 반면, 저주파 정규 단어와 비 단어는 음운론적 규칙의 하위 집합을 사용하여 처리한다고 가정한다.[194]

독서를 위한 단일 경로 모델은 컴퓨터 모델링 연구에서 지지를 발견했는데, 이것은 독자들이 음운학적으로 유사한 단어들과 그들의 정형화된 유사성으로 단어를 식별한다는 것을 암시한다.[194] 그러나 인지 및 병변 연구는 이중 경로 모델에 치우친다. 어린이와 성인에 대한 인지적 철자 연구는 철자가 규칙적인 단어와 비단어의 철자에 음운론적 규칙을 사용하는 반면 어휘적 기억력은 모든 유형의 불규칙한 단어와 고주파 단어의 철자를 쓰도록 접근된다고 제안한다.[194] 마찬가지로 병변 연구는 불규칙한 단어와 특정한 규칙적인 단어를 저장하는 데 어휘적 기억력이 사용되는 반면, 음운론적 규칙은 비단어의 철자를 쓰는 데 사용된다는 것을 보여준다.[194]

보다 최근에는 양전자 방출 단층 촬영과 fMRI를 이용한 신경영상 연구에서는 모든 단어 유형의 판독이 시각적 단어 형태 영역에서 시작되지만, 이후 어휘 메모리나 의미 정보에 대한 접근이 필요한지에 따라 다른 경로로 분기되는 균형 잡힌 모델을 제시하였다(특정할 것이다).이중모형 모델 아래 불규칙한 단어로 테드.[194] 2007 fMRI 연구는 철자 과제에서 정규 단어를 생산하도록 요청된 피험자들이 음운 처리에 사용되는 영역인 왼쪽 후방의 STG에서 더 큰 활성화를 보이는 반면, 불규칙적인 단어의 철자는 왼쪽 IFG와 왼쪽 SMG와 b와 같은 어휘적 기억과 의미 처리에 사용되는 영역의 더 큰 활성화를 유발한다는 것을 발견했다.o번째 반구 MTG [194]철자 비문어들은 왼쪽 STG와 양쪽 MTG와 ITG와 같은 두 경로의 멤버들에 접근하는 것으로 발견되었다.[194] 특히 철자법은 독해에도 중요한 왼쪽 방추형 회오리, 왼쪽 SMG 등의 영역에서의 활성화를 유도하는 것으로 밝혀져 독해와 쓰기 모두에 유사한 경로가 사용됨을 시사했다.[194]

알파벳과 영어가 아닌 문자의 인식과 신경학에 관한 정보는 훨씬 적다. 모든 언어는 형태론적 요소와 음운론적 요소를 가지고 있는데, 둘 중 하나는 문자 시스템에 의해 기록될 수 있다. 단어와 형태소를 녹음하는 대본은 로그그래픽으로 간주되는 반면, 음절이나 알파벳과 같은 음운론적인 부분을 녹음하는 대본은 음운그래픽이다.[195] 대부분의 시스템은 이 둘을 결합하고 로그와 음운 문자를 모두 가지고 있다.[195]

복잡성 측면에서, 쓰기 시스템은 "투명" 또는 "불투명"으로 특징지어질 수 있으며 "샤로우" 또는 "깊이"로 특징지어질 수 있다. "투명한" 시스템은 그래핀과 소리 사이의 분명한 일치성을 보이는 반면, "불투명한" 시스템에서는 이러한 관계가 덜 명백하다. "허용"과 "깊이"라는 용어는 어떤 시스템의 맞춤법이 음운학적 부분과 반대로 형태소를 나타내는 정도를 가리킨다.[195] 로그 시스템과 음절과 같이 더 큰 형태론적 또는 음운론적 세그먼트를 기록하는 시스템은 사용자의 기억력에 더 큰 요구를 한다.[195] 따라서 불투명하거나 심층적인 쓰기 시스템은 투명하거나 얕은 맞춤법을 사용하는 시스템보다 어휘 기억장치에 사용되는 뇌의 영역에 더 큰 수요를 일으킬 것으로 예상된다.

참고 항목

참조

- ^ Seidenberg MS, Petitto LA (1987). "Communication, symbolic communication, and language: Comment on Savage-Rumbaugh, McDonald, Sevcik, Hopkins, and Rupert (1986)". Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 116 (3): 279–287. doi:10.1037/0096-3445.116.3.279.

- ^ a b Geschwind N (June 1965). "Disconnexion syndromes in animals and man. I". review. Brain. 88 (2): 237–94. doi:10.1093/brain/88.2.237. PMID 5318481.

- ^ a b Hickok G, Poeppel D (May 2007). "The cortical organization of speech processing". review. Nature Reviews. Neuroscience. 8 (5): 393–402. doi:10.1038/nrn2113. PMID 17431404. S2CID 6199399.

- ^ a b Gow DW (June 2012). "The cortical organization of lexical knowledge: a dual lexicon model of spoken language processing". review. Brain and Language. 121 (3): 273–88. doi:10.1016/j.bandl.2012.03.005. PMC 3348354. PMID 22498237.

- ^ Poliva O (2017-09-20). "From where to what: a neuroanatomically based evolutionary model of the emergence of speech in humans". review. F1000Research. 4: 67. doi:10.12688/f1000research.6175.3. PMC 5600004. PMID 28928931.

자료는 이 출처에서 복사되었으며, Creative Commons Accountation 4.0 International License에 따라 이용할 수 있다.

자료는 이 출처에서 복사되었으며, Creative Commons Accountation 4.0 International License에 따라 이용할 수 있다. - ^ Poliva O (2016). "From Mimicry to Language: A Neuroanatomically Based Evolutionary Model of the Emergence of Vocal Language". review. Frontiers in Neuroscience. 10: 307. doi:10.3389/fnins.2016.00307. PMC 4928493. PMID 27445676.

자료는 이 출처에서 복사되었으며, Creative Commons Accountation 4.0 International License에 따라 이용할 수 있다.

자료는 이 출처에서 복사되었으며, Creative Commons Accountation 4.0 International License에 따라 이용할 수 있다. - ^ Pickles JO (2015). "Chapter 1: Auditory pathways: anatomy and physiology". In Aminoff MJ, Boller F, Swaab DF (eds.). Handbook of Clinical Neurology. review. 129. pp. 3–25. doi:10.1016/B978-0-444-62630-1.00001-9. ISBN 978-0-444-62630-1. PMID 25726260.

- ^ Lichteim L (1885-01-01). "On Aphasia". Brain. 7 (4): 433–484. doi:10.1093/brain/7.4.433. hdl:11858/00-001M-0000-002C-5780-B.

- ^ Wernicke C (1974). Der aphasische Symptomenkomplex. Springer Berlin Heidelberg. pp. 1–70. ISBN 978-3-540-06905-8.

- ^ Aboitiz F, García VR (December 1997). "The evolutionary origin of the language areas in the human brain. A neuroanatomical perspective". Brain Research. Brain Research Reviews. 25 (3): 381–96. doi:10.1016/s0165-0173(97)00053-2. PMID 9495565. S2CID 20704891.

- ^ a b Anderson JM, Gilmore R, Roper S, Crosson B, Bauer RM, Nadeau S, Beversdorf DQ, Cibula J, Rogish M, Kortencamp S, Hughes JD, Gonzalez Rothi LJ, Heilman KM (October 1999). "Conduction aphasia and the arcuate fasciculus: A reexamination of the Wernicke-Geschwind model". Brain and Language. 70 (1): 1–12. doi:10.1006/brln.1999.2135. PMID 10534369. S2CID 12171982.

- ^ DeWitt I, Rauschecker JP (November 2013). "Wernicke's area revisited: parallel streams and word processing". Brain and Language. 127 (2): 181–91. doi:10.1016/j.bandl.2013.09.014. PMC 4098851. PMID 24404576.

- ^ Dronkers NF (January 2000). "The pursuit of brain-language relationships". Brain and Language. 71 (1): 59–61. doi:10.1006/brln.1999.2212. PMID 10716807. S2CID 7224731.

- ^ a b c Dronkers NF, Wilkins DP, Van Valin RD, Redfern BB, Jaeger JJ (May 2004). "Lesion analysis of the brain areas involved in language comprehension". Cognition. 92 (1–2): 145–77. doi:10.1016/j.cognition.2003.11.002. hdl:11858/00-001M-0000-0012-6912-A. PMID 15037129. S2CID 10919645.

- ^ Mesulam MM, Thompson CK, Weintraub S, Rogalski EJ (August 2015). "The Wernicke conundrum and the anatomy of language comprehension in primary progressive aphasia". Brain. 138 (Pt 8): 2423–37. doi:10.1093/brain/awv154. PMC 4805066. PMID 26112340.

- ^ Poeppel D, Emmorey K, Hickok G, Pylkkänen L (October 2012). "Towards a new neurobiology of language". The Journal of Neuroscience. 32 (41): 14125–31. doi:10.1523/jneurosci.3244-12.2012. PMC 3495005. PMID 23055482.

- ^ Vignolo LA, Boccardi E, Caverni L (March 1986). "Unexpected CT-scan findings in global aphasia". Cortex; A Journal Devoted to the Study of the Nervous System and Behavior. 22 (1): 55–69. doi:10.1016/s0010-9452(86)80032-6. PMID 2423296. S2CID 4479679.

- ^ a b Bendor D, Wang X (August 2006). "Cortical representations of pitch in monkeys and humans". Current Opinion in Neurobiology. 16 (4): 391–9. doi:10.1016/j.conb.2006.07.001. PMC 4325365. PMID 16842992.

- ^ a b Rauschecker JP, Tian B, Hauser M (April 1995). "Processing of complex sounds in the macaque nonprimary auditory cortex". Science. 268 (5207): 111–4. Bibcode:1995Sci...268..111R. doi:10.1126/science.7701330. PMID 7701330.

- ^ a b de la Mothe LA, Blumell S, Kajikawa Y, Hackett TA (May 2006). "Cortical connections of the auditory cortex in marmoset monkeys: core and medial belt regions". The Journal of Comparative Neurology. 496 (1): 27–71. doi:10.1002/cne.20923. PMID 16528722. S2CID 38393074.

- ^ de la Mothe LA, Blumell S, Kajikawa Y, Hackett TA (May 2012). "Cortical connections of auditory cortex in marmoset monkeys: lateral belt and parabelt regions". Anatomical Record. 295 (5): 800–21. doi:10.1002/ar.22451. PMC 3379817. PMID 22461313.

- ^ Kaas JH, Hackett TA (October 2000). "Subdivisions of auditory cortex and processing streams in primates". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 97 (22): 11793–9. Bibcode:2000PNAS...9711793K. doi:10.1073/pnas.97.22.11793. PMC 34351. PMID 11050211.

- ^ Petkov CI, Kayser C, Augath M, Logothetis NK (July 2006). "Functional imaging reveals numerous fields in the monkey auditory cortex". PLOS Biology. 4 (7): e215. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0040215. PMC 1479693. PMID 16774452.

- ^ Morel A, Garraghty PE, Kaas JH (September 1993). "Tonotopic organization, architectonic fields, and connections of auditory cortex in macaque monkeys". The Journal of Comparative Neurology. 335 (3): 437–59. doi:10.1002/cne.903350312. PMID 7693772. S2CID 22872232.

- ^ Rauschecker JP, Tian B (October 2000). "Mechanisms and streams for processing of "what" and "where" in auditory cortex". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 97 (22): 11800–6. Bibcode:2000PNAS...9711800R. doi:10.1073/pnas.97.22.11800. PMC 34352. PMID 11050212.

- ^ Rauschecker JP, Tian B, Pons T, Mishkin M (May 1997). "Serial and parallel processing in rhesus monkey auditory cortex". The Journal of Comparative Neurology. 382 (1): 89–103. doi:10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19970526)382:1<89::aid-cne6>3.3.co;2-y. PMID 9136813.

- ^ Sweet RA, Dorph-Petersen KA, Lewis DA (October 2005). "Mapping auditory core, lateral belt, and parabelt cortices in the human superior temporal gyrus". The Journal of Comparative Neurology. 491 (3): 270–89. doi:10.1002/cne.20702. PMID 16134138. S2CID 40822276.

- ^ Wallace MN, Johnston PW, Palmer AR (April 2002). "Histochemical identification of cortical areas in the auditory region of the human brain". Experimental Brain Research. 143 (4): 499–508. doi:10.1007/s00221-002-1014-z. PMID 11914796. S2CID 24211906.

- ^ Da Costa S, van der Zwaag W, Marques JP, Frackowiak RS, Clarke S, Saenz M (October 2011). "Human primary auditory cortex follows the shape of Heschl's gyrus". The Journal of Neuroscience. 31 (40): 14067–75. doi:10.1523/jneurosci.2000-11.2011. PMC 6623669. PMID 21976491.

- ^ Humphries C, Liebenthal E, Binder JR (April 2010). "Tonotopic organization of human auditory cortex". NeuroImage. 50 (3): 1202–11. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.01.046. PMC 2830355. PMID 20096790.

- ^ Langers DR, van Dijk P (September 2012). "Mapping the tonotopic organization in human auditory cortex with minimally salient acoustic stimulation". Cerebral Cortex. 22 (9): 2024–38. doi:10.1093/cercor/bhr282. PMC 3412441. PMID 21980020.

- ^ Striem-Amit E, Hertz U, Amedi A (March 2011). "Extensive cochleotopic mapping of human auditory cortical fields obtained with phase-encoding fMRI". PLOS ONE. 6 (3): e17832. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...617832S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0017832. PMC 3063163. PMID 21448274.

- ^ Woods DL, Herron TJ, Cate AD, Yund EW, Stecker GC, Rinne T, Kang X (2010). "Functional properties of human auditory cortical fields". Frontiers in Systems Neuroscience. 4: 155. doi:10.3389/fnsys.2010.00155. PMC 3001989. PMID 21160558.

- ^ Gourévitch B, Le Bouquin Jeannès R, Faucon G, Liégeois-Chauvel C (March 2008). "Temporal envelope processing in the human auditory cortex: response and interconnections of auditory cortical areas" (PDF). Hearing Research. 237 (1–2): 1–18. doi:10.1016/j.heares.2007.12.003. PMID 18255243. S2CID 15271578.

- ^ Guéguin M, Le Bouquin-Jeannès R, Faucon G, Chauvel P, Liégeois-Chauvel C (February 2007). "Evidence of functional connectivity between auditory cortical areas revealed by amplitude modulation sound processing". Cerebral Cortex. 17 (2): 304–13. doi:10.1093/cercor/bhj148. PMC 2111045. PMID 16514106.

- ^ a b c Poliva O, Bestelmeyer PE, Hall M, Bultitude JH, Koller K, Rafal RD (September 2015). "Functional Mapping of the Human Auditory Cortex: fMRI Investigation of a Patient with Auditory Agnosia from Trauma to the Inferior Colliculus" (PDF). Cognitive and Behavioral Neurology. 28 (3): 160–80. doi:10.1097/wnn.0000000000000072. PMID 26413744. S2CID 913296.

- ^ Chang EF, Edwards E, Nagarajan SS, Fogelson N, Dalal SS, Canolty RT, Kirsch HE, Barbaro NM, Knight RT (June 2011). "Cortical spatio-temporal dynamics underlying phonological target detection in humans". Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 23 (6): 1437–46. doi:10.1162/jocn.2010.21466. PMC 3895406. PMID 20465359.

- ^ Muñoz M, Mishkin M, Saunders RC (September 2009). "Resection of the medial temporal lobe disconnects the rostral superior temporal gyrus from some of its projection targets in the frontal lobe and thalamus". Cerebral Cortex. 19 (9): 2114–30. doi:10.1093/cercor/bhn236. PMC 2722427. PMID 19150921.

- ^ a b Romanski LM, Bates JF, Goldman-Rakic PS (January 1999). "Auditory belt and parabelt projections to the prefrontal cortex in the rhesus monkey". The Journal of Comparative Neurology. 403 (2): 141–57. doi:10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19990111)403:2<141::aid-cne1>3.0.co;2-v. PMID 9886040.

- ^ Tanaka D (June 1976). "Thalamic projections of the dorsomedial prefrontal cortex in the rhesus monkey (Macaca mulatta)". Brain Research. 110 (1): 21–38. doi:10.1016/0006-8993(76)90206-7. PMID 819108. S2CID 21529048.

- ^ a b Perrodin C, Kayser C, Logothetis NK, Petkov CI (August 2011). "Voice cells in the primate temporal lobe". Current Biology. 21 (16): 1408–15. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2011.07.028. PMC 3398143. PMID 21835625.

- ^ a b c Petkov CI, Kayser C, Steudel T, Whittingstall K, Augath M, Logothetis NK (March 2008). "A voice region in the monkey brain". Nature Neuroscience. 11 (3): 367–74. doi:10.1038/nn2043. PMID 18264095. S2CID 5505773.

- ^ a b Poremba A, Malloy M, Saunders RC, Carson RE, Herscovitch P, Mishkin M (January 2004). "Species-specific calls evoke asymmetric activity in the monkey's temporal poles". Nature. 427 (6973): 448–51. Bibcode:2004Natur.427..448P. doi:10.1038/nature02268. PMID 14749833. S2CID 4402126.

- ^ Romanski LM, Averbeck BB, Diltz M (February 2005). "Neural representation of vocalizations in the primate ventrolateral prefrontal cortex". Journal of Neurophysiology. 93 (2): 734–47. doi:10.1152/jn.00675.2004. PMID 15371495.

- ^ Russ BE, Ackelson AL, Baker AE, Cohen YE (January 2008). "Coding of auditory-stimulus identity in the auditory non-spatial processing stream". Journal of Neurophysiology. 99 (1): 87–95. doi:10.1152/jn.01069.2007. PMC 4091985. PMID 18003874.

- ^ a b Tsunada J, Lee JH, Cohen YE (June 2011). "Representation of speech categories in the primate auditory cortex". Journal of Neurophysiology. 105 (6): 2634–46. doi:10.1152/jn.00037.2011. PMC 3118748. PMID 21346209.

- ^ Cusick CG, Seltzer B, Cola M, Griggs E (September 1995). "Chemoarchitectonics and corticocortical terminations within the superior temporal sulcus of the rhesus monkey: evidence for subdivisions of superior temporal polysensory cortex". The Journal of Comparative Neurology. 360 (3): 513–35. doi:10.1002/cne.903600312. PMID 8543656. S2CID 42281619.

- ^ Cohen YE, Russ BE, Gifford GW, Kiringoda R, MacLean KA (December 2004). "Selectivity for the spatial and nonspatial attributes of auditory stimuli in the ventrolateral prefrontal cortex". The Journal of Neuroscience. 24 (50): 11307–16. doi:10.1523/jneurosci.3935-04.2004. PMC 6730358. PMID 15601937.

- ^ Deacon TW (February 1992). "Cortical connections of the inferior arcuate sulcus cortex in the macaque brain". Brain Research. 573 (1): 8–26. doi:10.1016/0006-8993(92)90109-m. ISSN 0006-8993. PMID 1374284. S2CID 20670766.

- ^ Lewis JW, Van Essen DC (December 2000). "Corticocortical connections of visual, sensorimotor, and multimodal processing areas in the parietal lobe of the macaque monkey". The Journal of Comparative Neurology. 428 (1): 112–37. doi:10.1002/1096-9861(20001204)428:1<112::aid-cne8>3.0.co;2-9. PMID 11058227.

- ^ Roberts AC, Tomic DL, Parkinson CH, Roeling TA, Cutter DJ, Robbins TW, Everitt BJ (May 2007). "Forebrain connectivity of the prefrontal cortex in the marmoset monkey (Callithrix jacchus): an anterograde and retrograde tract-tracing study". The Journal of Comparative Neurology. 502 (1): 86–112. doi:10.1002/cne.21300. PMID 17335041. S2CID 18262007.

- ^ a b Schmahmann JD, Pandya DN, Wang R, Dai G, D'Arceuil HE, de Crespigny AJ, Wedeen VJ (March 2007). "Association fibre pathways of the brain: parallel observations from diffusion spectrum imaging and autoradiography". Brain. 130 (Pt 3): 630–53. doi:10.1093/brain/awl359. PMID 17293361.

- ^ Seltzer B, Pandya DN (July 1984). "Further observations on parieto-temporal connections in the rhesus monkey". Experimental Brain Research. 55 (2): 301–12. doi:10.1007/bf00237280. PMID 6745368. S2CID 20167953.

- ^ Catani M, Jones DK, ffytche DH (January 2005). "Perisylvian language networks of the human brain". Annals of Neurology. 57 (1): 8–16. doi:10.1002/ana.20319. PMID 15597383. S2CID 17743067.

- ^ Frey S, Campbell JS, Pike GB, Petrides M (November 2008). "Dissociating the human language pathways with high angular resolution diffusion fiber tractography". The Journal of Neuroscience. 28 (45): 11435–44. doi:10.1523/jneurosci.2388-08.2008. PMC 6671318. PMID 18987180.

- ^ Makris N, Papadimitriou GM, Kaiser JR, Sorg S, Kennedy DN, Pandya DN (April 2009). "Delineation of the middle longitudinal fascicle in humans: a quantitative, in vivo, DT-MRI study". Cerebral Cortex. 19 (4): 777–85. doi:10.1093/cercor/bhn124. PMC 2651473. PMID 18669591.

- ^ Menjot de Champfleur N, Lima Maldonado I, Moritz-Gasser S, Machi P, Le Bars E, Bonafé A, Duffau H (January 2013). "Middle longitudinal fasciculus delineation within language pathways: a diffusion tensor imaging study in human". European Journal of Radiology. 82 (1): 151–7. doi:10.1016/j.ejrad.2012.05.034. PMID 23084876.

- ^ Turken AU, Dronkers NF (2011). "The neural architecture of the language comprehension network: converging evidence from lesion and connectivity analyses". Frontiers in Systems Neuroscience. 5: 1. doi:10.3389/fnsys.2011.00001. PMC 3039157. PMID 21347218.

- ^ Saur D, Kreher BW, Schnell S, Kümmerer D, Kellmeyer P, Vry MS, Umarova R, Musso M, Glauche V, Abel S, Huber W, Rijntjes M, Hennig J, Weiller C (November 2008). "Ventral and dorsal pathways for language". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 105 (46): 18035–40. Bibcode:2008PNAS..10518035S. doi:10.1073/pnas.0805234105. PMC 2584675. PMID 19004769.

- ^ Yin P, Mishkin M, Sutter M, Fritz JB (December 2008). "Early stages of melody processing: stimulus-sequence and task-dependent neuronal activity in monkey auditory cortical fields A1 and R". Journal of Neurophysiology. 100 (6): 3009–29. doi:10.1152/jn.00828.2007. PMC 2604844. PMID 18842950.

- ^ Steinschneider M, Volkov IO, Fishman YI, Oya H, Arezzo JC, Howard MA (February 2005). "Intracortical responses in human and monkey primary auditory cortex support a temporal processing mechanism for encoding of the voice onset time phonetic parameter". Cerebral Cortex. 15 (2): 170–86. doi:10.1093/cercor/bhh120. PMID 15238437.

- ^ Russ BE, Ackelson AL, Baker AE, Cohen YE (January 2008). "Coding of auditory-stimulus identity in the auditory non-spatial processing stream". Journal of Neurophysiology. 99 (1): 87–95. doi:10.1152/jn.01069.2007. PMC 4091985. PMID 18003874.

- ^ Joly O, Pallier C, Ramus F, Pressnitzer D, Vanduffel W, Orban GA (September 2012). "Processing of vocalizations in humans and monkeys: a comparative fMRI study" (PDF). NeuroImage. 62 (3): 1376–89. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.05.070. PMID 22659478. S2CID 9441377.

- ^ Scheich H, Baumgart F, Gaschler-Markefski B, Tegeler C, Tempelmann C, Heinze HJ, Schindler F, Stiller D (February 1998). "Functional magnetic resonance imaging of a human auditory cortex area involved in foreground-background decomposition". The European Journal of Neuroscience. 10 (2): 803–9. doi:10.1046/j.1460-9568.1998.00086.x. PMID 9749748. S2CID 42898063.

- ^ Zatorre RJ, Bouffard M, Belin P (April 2004). "Sensitivity to auditory object features in human temporal neocortex". The Journal of Neuroscience. 24 (14): 3637–42. doi:10.1523/jneurosci.5458-03.2004. PMC 6729744. PMID 15071112.

- ^ a b Binder JR, Desai RH, Graves WW, Conant LL (December 2009). "Where is the semantic system? A critical review and meta-analysis of 120 functional neuroimaging studies". Cerebral Cortex. 19 (12): 2767–96. doi:10.1093/cercor/bhp055. PMC 2774390. PMID 19329570.

- ^ Davis MH, Johnsrude IS (April 2003). "Hierarchical processing in spoken language comprehension". The Journal of Neuroscience. 23 (8): 3423–31. doi:10.1523/jneurosci.23-08-03423.2003. PMC 6742313. PMID 12716950.

- ^ Liebenthal E, Binder JR, Spitzer SM, Possing ET, Medler DA (October 2005). "Neural substrates of phonemic perception". Cerebral Cortex. 15 (10): 1621–31. doi:10.1093/cercor/bhi040. PMID 15703256.

- ^ Narain C, Scott SK, Wise RJ, Rosen S, Leff A, Iversen SD, Matthews PM (December 2003). "Defining a left-lateralized response specific to intelligible speech using fMRI". Cerebral Cortex. 13 (12): 1362–8. doi:10.1093/cercor/bhg083. PMID 14615301.

- ^ Obleser J, Boecker H, Drzezga A, Haslinger B, Hennenlotter A, Roettinger M, Eulitz C, Rauschecker JP (July 2006). "Vowel sound extraction in anterior superior temporal cortex". Human Brain Mapping. 27 (7): 562–71. doi:10.1002/hbm.20201. PMC 6871493. PMID 16281283.

- ^ Obleser J, Zimmermann J, Van Meter J, Rauschecker JP (October 2007). "Multiple stages of auditory speech perception reflected in event-related FMRI". Cerebral Cortex. 17 (10): 2251–7. doi:10.1093/cercor/bhl133. PMID 17150986.

- ^ Scott SK, Blank CC, Rosen S, Wise RJ (December 2000). "Identification of a pathway for intelligible speech in the left temporal lobe". Brain. 123 (12): 2400–6. doi:10.1093/brain/123.12.2400. PMC 5630088. PMID 11099443.

- ^ Belin P, Zatorre RJ (November 2003). "Adaptation to speaker's voice in right anterior temporal lobe". NeuroReport. 14 (16): 2105–2109. doi:10.1097/00001756-200311140-00019. PMID 14600506. S2CID 34183900.

- ^ Benson RR, Whalen DH, Richardson M, Swainson B, Clark VP, Lai S, Liberman AM (September 2001). "Parametrically dissociating speech and nonspeech perception in the brain using fMRI". Brain and Language. 78 (3): 364–96. doi:10.1006/brln.2001.2484. PMID 11703063. S2CID 15328590.

- ^ Leaver AM, Rauschecker JP (June 2010). "Cortical representation of natural complex sounds: effects of acoustic features and auditory object category". The Journal of Neuroscience. 30 (22): 7604–12. doi:10.1523/jneurosci.0296-10.2010. PMC 2930617. PMID 20519535.

- ^ Lewis JW, Phinney RE, Brefczynski-Lewis JA, DeYoe EA (August 2006). "Lefties get it "right" when hearing tool sounds". Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 18 (8): 1314–30. doi:10.1162/jocn.2006.18.8.1314. PMID 16859417. S2CID 14049095.

- ^ Maeder PP, Meuli RA, Adriani M, Bellmann A, Fornari E, Thiran JP, Pittet A, Clarke S (October 2001). "Distinct pathways involved in sound recognition and localization: a human fMRI study" (PDF). NeuroImage. 14 (4): 802–16. doi:10.1006/nimg.2001.0888. PMID 11554799. S2CID 1388647.

- ^ Viceic D, Fornari E, Thiran JP, Maeder PP, Meuli R, Adriani M, Clarke S (November 2006). "Human auditory belt areas specialized in sound recognition: a functional magnetic resonance imaging study" (PDF). NeuroReport. 17 (16): 1659–62. doi:10.1097/01.wnr.0000239962.75943.dd. PMID 17047449. S2CID 14482187.

- ^ Shultz S, Vouloumanos A, Pelphrey K (May 2012). "The superior temporal sulcus differentiates communicative and noncommunicative auditory signals". Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 24 (5): 1224–32. doi:10.1162/jocn_a_00208. PMID 22360624. S2CID 10784270.

- ^ DeWitt I, Rauschecker JP (February 2012). "Phoneme and word recognition in the auditory ventral stream". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 109 (8): E505-14. doi:10.1073/pnas.1113427109. PMC 3286918. PMID 22308358.

- ^ a b c d Lachaux JP, Jerbi K, Bertrand O, Minotti L, Hoffmann D, Schoendorff B, Kahane P (October 2007). "A blueprint for real-time functional mapping via human intracranial recordings". PLOS ONE. 2 (10): e1094. Bibcode:2007PLoSO...2.1094L. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0001094. PMC 2040217. PMID 17971857.

- ^ a b Matsumoto R, Imamura H, Inouchi M, Nakagawa T, Yokoyama Y, Matsuhashi M, Mikuni N, Miyamoto S, Fukuyama H, Takahashi R, Ikeda A (April 2011). "Left anterior temporal cortex actively engages in speech perception: A direct cortical stimulation study". Neuropsychologia. 49 (5): 1350–1354. doi:10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2011.01.023. hdl:2433/141342. PMID 21251921. S2CID 1831334.

- ^ a b c d Roux FE, Miskin K, Durand JB, Sacko O, Réhault E, Tanova R, Démonet JF (October 2015). "Electrostimulation mapping of comprehension of auditory and visual words". Cortex; A Journal Devoted to the Study of the Nervous System and Behavior. 71: 398–408. doi:10.1016/j.cortex.2015.07.001. PMID 26332785. S2CID 39964328.

- ^ Fritz J, Mishkin M, Saunders RC (June 2005). "In search of an auditory engram". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 102 (26): 9359–64. Bibcode:2005PNAS..102.9359F. doi:10.1073/pnas.0503998102. PMC 1166637. PMID 15967995.

- ^ Stepien LS, Cordeau JP, Rasmussen T (1960). "The effect of temporal lobe and hippocampal lesions on auditory and visual recent memory in monkeys". Brain. 83 (3): 470–489. doi:10.1093/brain/83.3.470. ISSN 0006-8950.

- ^ Strominger NL, Oesterreich RE, Neff WD (June 1980). "Sequential auditory and visual discriminations after temporal lobe ablation in monkeys". Physiology & Behavior. 24 (6): 1149–56. doi:10.1016/0031-9384(80)90062-1. PMID 6774349. S2CID 7494152.

- ^ Kaiser J, Ripper B, Birbaumer N, Lutzenberger W (October 2003). "Dynamics of gamma-band activity in human magnetoencephalogram during auditory pattern working memory". NeuroImage. 20 (2): 816–27. doi:10.1016/s1053-8119(03)00350-1. PMID 14568454. S2CID 19373941.

- ^ Buchsbaum BR, Olsen RK, Koch P, Berman KF (November 2005). "Human dorsal and ventral auditory streams subserve rehearsal-based and echoic processes during verbal working memory". Neuron. 48 (4): 687–97. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2005.09.029. PMID 16301183. S2CID 13202604.

- ^ Scott BH, Mishkin M, Yin P (July 2012). "Monkeys have a limited form of short-term memory in audition". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 109 (30): 12237–41. Bibcode:2012PNAS..10912237S. doi:10.1073/pnas.1209685109. PMC 3409773. PMID 22778411.

- ^ Noppeney U, Patterson K, Tyler LK, Moss H, Stamatakis EA, Bright P, Mummery C, Price CJ (April 2007). "Temporal lobe lesions and semantic impairment: a comparison of herpes simplex virus encephalitis and semantic dementia". Brain. 130 (Pt 4): 1138–47. doi:10.1093/brain/awl344. PMID 17251241.

- ^ Patterson K, Nestor PJ, Rogers TT (December 2007). "Where do you know what you know? The representation of semantic knowledge in the human brain". Nature Reviews. Neuroscience. 8 (12): 976–87. doi:10.1038/nrn2277. PMID 18026167. S2CID 7310189.

- ^ Schwartz MF, Kimberg DY, Walker GM, Faseyitan O, Brecher A, Dell GS, Coslett HB (December 2009). "Anterior temporal involvement in semantic word retrieval: voxel-based lesion-symptom mapping evidence from aphasia". Brain. 132 (Pt 12): 3411–27. doi:10.1093/brain/awp284. PMC 2792374. PMID 19942676.

- ^ Hamberger MJ, McClelland S, McKhann GM, Williams AC, Goodman RR (March 2007). "Distribution of auditory and visual naming sites in nonlesional temporal lobe epilepsy patients and patients with space-occupying temporal lobe lesions". Epilepsia. 48 (3): 531–8. doi:10.1111/j.1528-1167.2006.00955.x. PMID 17326797. S2CID 12642281.

- ^ a b c Duffau H (March 2008). "The anatomo-functional connectivity of language revisited. New insights provided by electrostimulation and tractography". Neuropsychologia. 46 (4): 927–34. doi:10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2007.10.025. PMID 18093622. S2CID 40514753.

- ^ Vigneau M, Beaucousin V, Hervé PY, Duffau H, Crivello F, Houdé O, Mazoyer B, Tzourio-Mazoyer N (May 2006). "Meta-analyzing left hemisphere language areas: phonology, semantics, and sentence processing". NeuroImage. 30 (4): 1414–32. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.11.002. PMID 16413796. S2CID 8870165.

- ^ a b Creutzfeldt O, Ojemann G, Lettich E (October 1989). "Neuronal activity in the human lateral temporal lobe. I. Responses to speech". Experimental Brain Research. 77 (3): 451–75. doi:10.1007/bf00249600. hdl:11858/00-001M-0000-002C-89EA-3. PMID 2806441. S2CID 19952034.

- ^ Mazoyer BM, Tzourio N, Frak V, Syrota A, Murayama N, Levrier O, Salamon G, Dehaene S, Cohen L, Mehler J (October 1993). "The cortical representation of speech" (PDF). Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 5 (4): 467–79. doi:10.1162/jocn.1993.5.4.467. PMID 23964919. S2CID 22265355.

- ^ Humphries C, Love T, Swinney D, Hickok G (October 2005). "Response of anterior temporal cortex to syntactic and prosodic manipulations during sentence processing". Human Brain Mapping. 26 (2): 128–38. doi:10.1002/hbm.20148. PMC 6871757. PMID 15895428.

- ^ Humphries C, Willard K, Buchsbaum B, Hickok G (June 2001). "Role of anterior temporal cortex in auditory sentence comprehension: an fMRI study". NeuroReport. 12 (8): 1749–52. doi:10.1097/00001756-200106130-00046. PMID 11409752. S2CID 13039857.

- ^ Vandenberghe R, Nobre AC, Price CJ (May 2002). "The response of left temporal cortex to sentences". Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 14 (4): 550–60. doi:10.1162/08989290260045800. PMID 12126497. S2CID 21607482.

- ^ Friederici AD, Rüschemeyer SA, Hahne A, Fiebach CJ (February 2003). "The role of left inferior frontal and superior temporal cortex in sentence comprehension: localizing syntactic and semantic processes". Cerebral Cortex. 13 (2): 170–7. doi:10.1093/cercor/13.2.170. PMID 12507948.

- ^ Xu J, Kemeny S, Park G, Frattali C, Braun A (2005). "Language in context: emergent features of word, sentence, and narrative comprehension". NeuroImage. 25 (3): 1002–15. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.12.013. PMID 15809000. S2CID 25570583.

- ^ Rogalsky C, Hickok G (April 2009). "Selective attention to semantic and syntactic features modulates sentence processing networks in anterior temporal cortex". Cerebral Cortex. 19 (4): 786–96. doi:10.1093/cercor/bhn126. PMC 2651476. PMID 18669589.

- ^ Pallier C, Devauchelle AD, Dehaene S (February 2011). "Cortical representation of the constituent structure of sentences". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 108 (6): 2522–7. doi:10.1073/pnas.1018711108. PMC 3038732. PMID 21224415.

- ^ Brennan J, Nir Y, Hasson U, Malach R, Heeger DJ, Pylkkänen L (February 2012). "Syntactic structure building in the anterior temporal lobe during natural story listening". Brain and Language. 120 (2): 163–73. doi:10.1016/j.bandl.2010.04.002. PMC 2947556. PMID 20472279.

- ^ Kotz SA, von Cramon DY, Friederici AD (October 2003). "Differentiation of syntactic processes in the left and right anterior temporal lobe: Event-related brain potential evidence from lesion patients". Brain and Language. 87 (1): 135–136. doi:10.1016/s0093-934x(03)00236-0. S2CID 54320415.

- ^ Martin RC, Shelton JR, Yaffee LS (February 1994). "Language processing and working memory: Neuropsychological evidence for separate phonological and semantic capacities". Journal of Memory and Language. 33 (1): 83–111. doi:10.1006/jmla.1994.1005.

- ^ Magnusdottir S, Fillmore P, den Ouden DB, Hjaltason H, Rorden C, Kjartansson O, Bonilha L, Fridriksson J (October 2013). "Damage to left anterior temporal cortex predicts impairment of complex syntactic processing: a lesion-symptom mapping study". Human Brain Mapping. 34 (10): 2715–23. doi:10.1002/hbm.22096. PMC 6869931. PMID 22522937.

- ^ Bornkessel-Schlesewsky I, Schlesewsky M, Small SL, Rauschecker JP (March 2015). "Neurobiological roots of language in primate audition: common computational properties". Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 19 (3): 142–50. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2014.12.008. PMC 4348204. PMID 25600585.

- ^ Hickok G, Okada K, Barr W, Pa J, Rogalsky C, Donnelly K, Barde L, Grant A (December 2008). "Bilateral capacity for speech sound processing in auditory comprehension: evidence from Wada procedures". Brain and Language. 107 (3): 179–84. doi:10.1016/j.bandl.2008.09.006. PMC 2644214. PMID 18976806.

- ^ Zaidel E (September 1976). "Auditory Vocabulary of the Right Hemisphere Following Brain Bisection or Hemidecortication". Cortex. 12 (3): 191–211. doi:10.1016/s0010-9452(76)80001-9. ISSN 0010-9452. PMID 1000988. S2CID 4479925.

- ^ Poeppel D (October 2001). "Pure word deafness and the bilateral processing of the speech code". Cognitive Science. 25 (5): 679–693. doi:10.1016/s0364-0213(01)00050-7.

- ^ Ulrich G (May 1978). "Interhemispheric functional relationships in auditory agnosia. An analysis of the preconditions and a conceptual model". Brain and Language. 5 (3): 286–300. doi:10.1016/0093-934x(78)90027-5. PMID 656899. S2CID 33841186.

- ^ Stewart L, Walsh V, Frith U, Rothwell JC (March 2001). "TMS produces two dissociable types of speech disruption" (PDF). NeuroImage. 13 (3): 472–8. doi:10.1006/nimg.2000.0701. PMID 11170812. S2CID 10392466.

- ^ Acheson DJ, Hamidi M, Binder JR, Postle BR (June 2011). "A common neural substrate for language production and verbal working memory". Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 23 (6): 1358–67. doi:10.1162/jocn.2010.21519. PMC 3053417. PMID 20617889.

- ^ Desmurget M, Reilly KT, Richard N, Szathmari A, Mottolese C, Sirigu A (May 2009). "Movement intention after parietal cortex stimulation in humans". Science. 324 (5928): 811–3. Bibcode:2009Sci...324..811D. doi:10.1126/science.1169896. PMID 19423830. S2CID 6555881.

- ^ Edwards E, Nagarajan SS, Dalal SS, Canolty RT, Kirsch HE, Barbaro NM, Knight RT (March 2010). "Spatiotemporal imaging of cortical activation during verb generation and picture naming". NeuroImage. 50 (1): 291–301. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.12.035. PMC 2957470. PMID 20026224.

- ^ Boatman D, Gordon B, Hart J, Selnes O, Miglioretti D, Lenz F (August 2000). "Transcortical sensory aphasia: revisited and revised". Brain. 123 (8): 1634–42. doi:10.1093/brain/123.8.1634. PMID 10908193.

- ^ a b c Turkeltaub PE, Coslett HB (July 2010). "Localization of sublexical speech perception components". Brain and Language. 114 (1): 1–15. doi:10.1016/j.bandl.2010.03.008. PMC 2914564. PMID 20413149.

- ^ Chang EF, Rieger JW, Johnson K, Berger MS, Barbaro NM, Knight RT (November 2010). "Categorical speech representation in human superior temporal gyrus". Nature Neuroscience. 13 (11): 1428–32. doi:10.1038/nn.2641. PMC 2967728. PMID 20890293.

- ^ Buchsbaum BR, Hickok G, Humphries C (September 2001). "Role of left posterior superior temporal gyrus in phonological processing for speech perception and production". Cognitive Science. 25 (5): 663–678. doi:10.1207/s15516709cog2505_2. ISSN 0364-0213.

- ^ Wise RJ, Scott SK, Blank SC, Mummery CJ, Murphy K, Warburton EA (January 2001). "Separate neural subsystems within 'Wernicke's area'". Brain. 124 (Pt 1): 83–95. doi:10.1093/brain/124.1.83. PMID 11133789.

- ^ Hickok G, Buchsbaum B, Humphries C, Muftuler T (July 2003). "Auditory-motor interaction revealed by fMRI: speech, music, and working memory in area Spt". Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 15 (5): 673–82. doi:10.1162/089892903322307393. PMID 12965041.

- ^ Warren JE, Wise RJ, Warren JD (December 2005). "Sounds do-able: auditory-motor transformations and the posterior temporal plane". Trends in Neurosciences. 28 (12): 636–43. doi:10.1016/j.tins.2005.09.010. PMID 16216346. S2CID 36678139.

- ^ Hickok G, Poeppel D (May 2007). "The cortical organization of speech processing". Nature Reviews. Neuroscience. 8 (5): 393–402. doi:10.1038/nrn2113. PMID 17431404. S2CID 6199399.

- ^ Karbe H, Herholz K, Weber-Luxenburger G, Ghaemi M, Heiss WD (June 1998). "Cerebral networks and functional brain asymmetry: evidence from regional metabolic changes during word repetition". Brain and Language. 63 (1): 108–21. doi:10.1006/brln.1997.1937. PMID 9642023. S2CID 31335617.

- ^ Giraud AL, Price CJ (August 2001). "The constraints functional neuroimaging places on classical models of auditory word processing". Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 13 (6): 754–65. doi:10.1162/08989290152541421. PMID 11564320. S2CID 13916709.

- ^ Graves WW, Grabowski TJ, Mehta S, Gupta P (September 2008). "The left posterior superior temporal gyrus participates specifically in accessing lexical phonology". Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 20 (9): 1698–710. doi:10.1162/jocn.2008.20113. PMC 2570618. PMID 18345989.

- ^ a b Towle VL, Yoon HA, Castelle M, Edgar JC, Biassou NM, Frim DM, Spire JP, Kohrman MH (August 2008). "ECoG gamma activity during a language task: differentiating expressive and receptive speech areas". Brain. 131 (Pt 8): 2013–27. doi:10.1093/brain/awn147. PMC 2724904. PMID 18669510.

- ^ Selnes OA, Knopman DS, Niccum N, Rubens AB (June 1985). "The critical role of Wernicke's area in sentence repetition". Annals of Neurology. 17 (6): 549–57. doi:10.1002/ana.410170604. PMID 4026225. S2CID 12914191.

- ^ Axer H, von Keyserlingk AG, Berks G, von Keyserlingk DG (March 2001). "Supra- and infrasylvian conduction aphasia". Brain and Language. 76 (3): 317–31. doi:10.1006/brln.2000.2425. PMID 11247647. S2CID 25406527.

- ^ Bartha L, Benke T (April 2003). "Acute conduction aphasia: an analysis of 20 cases". Brain and Language. 85 (1): 93–108. doi:10.1016/s0093-934x(02)00502-3. PMID 12681350. S2CID 18466425.

- ^ Baldo JV, Katseff S, Dronkers NF (March 2012). "Brain Regions Underlying Repetition and Auditory-Verbal Short-term Memory Deficits in Aphasia: Evidence from Voxel-based Lesion Symptom Mapping". Aphasiology. 26 (3–4): 338–354. doi:10.1080/02687038.2011.602391. PMC 4070523. PMID 24976669.

- ^ Baldo JV, Klostermann EC, Dronkers NF (May 2008). "It's either a cook or a baker: patients with conduction aphasia get the gist but lose the trace". Brain and Language. 105 (2): 134–40. doi:10.1016/j.bandl.2007.12.007. PMID 18243294. S2CID 997735.

- ^ Fridriksson J, Kjartansson O, Morgan PS, Hjaltason H, Magnusdottir S, Bonilha L, Rorden C (August 2010). "Impaired speech repetition and left parietal lobe damage". The Journal of Neuroscience. 30 (33): 11057–61. doi:10.1523/jneurosci.1120-10.2010. PMC 2936270. PMID 20720112.

- ^ Buchsbaum BR, Baldo J, Okada K, Berman KF, Dronkers N, D'Esposito M, Hickok G (December 2011). "Conduction aphasia, sensory-motor integration, and phonological short-term memory - an aggregate analysis of lesion and fMRI data". Brain and Language. 119 (3): 119–28. doi:10.1016/j.bandl.2010.12.001. PMC 3090694. PMID 21256582.

- ^ Yamada K, Nagakane Y, Mizuno T, Hosomi A, Nakagawa M, Nishimura T (March 2007). "MR tractography depicting damage to the arcuate fasciculus in a patient with conduction aphasia". Neurology. 68 (10): 789. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000256348.65744.b2. PMID 17339591.

- ^ Breier JI, Hasan KM, Zhang W, Men D, Papanicolaou AC (March 2008). "Language dysfunction after stroke and damage to white matter tracts evaluated using diffusion tensor imaging". AJNR. American Journal of Neuroradiology. 29 (3): 483–7. doi:10.3174/ajnr.A0846. PMC 3073452. PMID 18039757.

- ^ Zhang Y, Wang C, Zhao X, Chen H, Han Z, Wang Y (September 2010). "Diffusion tensor imaging depicting damage to the arcuate fasciculus in patients with conduction aphasia: a study of the Wernicke-Geschwind model". Neurological Research. 32 (7): 775–8. doi:10.1179/016164109x12478302362653. PMID 19825277. S2CID 22960870.

- ^ Jones OP, Prejawa S, Hope TM, Oberhuber M, Seghier ML, Leff AP, Green DW, Price CJ (2014). "Sensory-to-motor integration during auditory repetition: a combined fMRI and lesion study". Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. 8: 24. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2014.00024. PMC 3908611. PMID 24550807.

- ^ Quigg M, Fountain NB (March 1999). "Conduction aphasia elicited by stimulation of the left posterior superior temporal gyrus". Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry. 66 (3): 393–6. doi:10.1136/jnnp.66.3.393. PMC 1736266. PMID 10084542.

- ^ Quigg M, Geldmacher DS, Elias WJ (May 2006). "Conduction aphasia as a function of the dominant posterior perisylvian cortex. Report of two cases". Journal of Neurosurgery. 104 (5): 845–8. doi:10.3171/jns.2006.104.5.845. PMID 16703895.

- ^ Service E, Kohonen V (April 1995). "Is the relation between phonological memory and foreign language learning accounted for by vocabulary acquisition?". Applied Psycholinguistics. 16 (2): 155–172. doi:10.1017/S0142716400007062.

- ^ Service E (July 1992). "Phonology, working memory, and foreign-language learning". The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology. A, Human Experimental Psychology. 45 (1): 21–50. doi:10.1080/14640749208401314. PMID 1636010. S2CID 43268252.

- ^ Matsumoto R, Nair DR, LaPresto E, Najm I, Bingaman W, Shibasaki H, Lüders HO (October 2004). "Functional connectivity in the human language system: a cortico-cortical evoked potential study". Brain. 127 (Pt 10): 2316–30. doi:10.1093/brain/awh246. PMID 15269116.

- ^ Kimura D, Watson N (November 1989). "The relation between oral movement control and speech". Brain and Language. 37 (4): 565–90. doi:10.1016/0093-934x(89)90112-0. PMID 2479446. S2CID 39913744.

- ^ Tourville JA, Reilly KJ, Guenther FH (February 2008). "Neural mechanisms underlying auditory feedback control of speech". NeuroImage. 39 (3): 1429–43. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.09.054. PMC 3658624. PMID 18035557.

- ^ Chang EF, Rieger JW, Johnson K, Berger MS, Barbaro NM, Knight RT (November 2010). "Categorical speech representation in human superior temporal gyrus". Nature Neuroscience. 13 (11): 1428–32. doi:10.1038/nn.2641. PMC 2967728. PMID 20890293.

- ^ Nath AR, Beauchamp MS (January 2012). "A neural basis for interindividual differences in the McGurk effect, a multisensory speech illusion". NeuroImage. 59 (1): 781–7. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.07.024. PMC 3196040. PMID 21787869.

- ^ Beauchamp MS, Nath AR, Pasalar S (February 2010). "fMRI-Guided transcranial magnetic stimulation reveals that the superior temporal sulcus is a cortical locus of the McGurk effect". The Journal of Neuroscience. 30 (7): 2414–7. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4865-09.2010. PMC 2844713. PMID 20164324.

- ^ McGettigan C, Faulkner A, Altarelli I, Obleser J, Baverstock H, Scott SK (April 2012). "Speech comprehension aided by multiple modalities: behavioural and neural interactions". Neuropsychologia. 50 (5): 762–76. doi:10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2012.01.010. PMC 4050300. PMID 22266262.

- ^ Stevenson RA, James TW (February 2009). "Audiovisual integration in human superior temporal sulcus: Inverse effectiveness and the neural processing of speech and object recognition". NeuroImage. 44 (3): 1210–23. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.09.034. PMID 18973818. S2CID 8342349.

- ^ Bernstein LE, Jiang J, Pantazis D, Lu ZL, Joshi A (October 2011). "Visual phonetic processing localized using speech and nonspeech face gestures in video and point-light displays". Human Brain Mapping. 32 (10): 1660–76. doi:10.1002/hbm.21139. PMC 3120928. PMID 20853377.

- ^ Campbell R (March 2008). "The processing of audio-visual speech: empirical and neural bases". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences. 363 (1493): 1001–10. doi:10.1098/rstb.2007.2155. PMC 2606792. PMID 17827105.

- ^ Schwartz MF, Faseyitan O, Kim J, Coslett HB (December 2012). "The dorsal stream contribution to phonological retrieval in object naming". Brain. 135 (Pt 12): 3799–814. doi:10.1093/brain/aws300. PMC 3525060. PMID 23171662.

- ^ Schwartz MF, Kimberg DY, Walker GM, Faseyitan O, Brecher A, Dell GS, Coslett HB (December 2009). "Anterior temporal involvement in semantic word retrieval: voxel-based lesion-symptom mapping evidence from aphasia". Brain. 132 (Pt 12): 3411–27. doi:10.1093/brain/awp284. PMC 2792374. PMID 19942676.

- ^ Ojemann GA (June 1983). "Brain organization for language from the perspective of electrical stimulation mapping". Behavioral and Brain Sciences. 6 (2): 189–206. doi:10.1017/S0140525X00015491. ISSN 1469-1825.

- ^ Cornelissen K, Laine M, Renvall K, Saarinen T, Martin N, Salmelin R (June 2004). "Learning new names for new objects: cortical effects as measured by magnetoencephalography". Brain and Language. 89 (3): 617–22. doi:10.1016/j.bandl.2003.12.007. PMID 15120553. S2CID 32224334.

- ^ Hartwigsen G, Baumgaertner A, Price CJ, Koehnke M, Ulmer S, Siebner HR (September 2010). "Phonological decisions require both the left and right supramarginal gyri". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 107 (38): 16494–9. Bibcode:2010PNAS..10716494H. doi:10.1073/pnas.1008121107. PMC 2944751. PMID 20807747.

- ^ Cornelissen K, Laine M, Tarkiainen A, Järvensivu T, Martin N, Salmelin R (April 2003). "Adult brain plasticity elicited by anomia treatment". Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 15 (3): 444–61. doi:10.1162/089892903321593153. PMID 12729495. S2CID 1597939.

- ^ Mechelli A, Crinion JT, Noppeney U, O'Doherty J, Ashburner J, Frackowiak RS, Price CJ (October 2004). "Neurolinguistics: structural plasticity in the bilingual brain". Nature. 431 (7010): 757. Bibcode:2004Natur.431..757M. doi:10.1038/431757a. hdl:11858/00-001M-0000-0013-D79B-1. PMID 15483594. S2CID 4338340.

- ^ Green DW, Crinion J, Price CJ (July 2007). "Exploring cross-linguistic vocabulary effects on brain structures using voxel-based morphometry". Bilingualism. 10 (2): 189–199. doi:10.1017/S1366728907002933. PMC 2312335. PMID 18418473.

- ^ Willness C (2016-01-08). "The Oxford handbook of organizational climate and culture By Benjamin Schneider & Karen M. Barbera (Eds.) New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2014. ISBN 978-0-19-986071-5". Book Reviews. British Journal of Psychology. 107 (1): 201–202. doi:10.1111/bjop.12170.

- ^ Lee H, Devlin JT, Shakeshaft C, Stewart LH, Brennan A, Glensman J, Pitcher K, Crinion J, Mechelli A, Frackowiak RS, Green DW, Price CJ (January 2007). "Anatomical traces of vocabulary acquisition in the adolescent brain". The Journal of Neuroscience. 27 (5): 1184–9. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4442-06.2007. PMC 6673201. PMID 17267574.

- ^ Richardson FM, Thomas MS, Filippi R, Harth H, Price CJ (May 2010). "Contrasting effects of vocabulary knowledge on temporal and parietal brain structure across lifespan". Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 22 (5): 943–54. doi:10.1162/jocn.2009.21238. PMC 2860571. PMID 19366285.

- ^ Jobard G, Crivello F, Tzourio-Mazoyer N (October 2003). "Evaluation of the dual route theory of reading: a metanalysis of 35 neuroimaging studies". NeuroImage. 20 (2): 693–712. doi:10.1016/s1053-8119(03)00343-4. PMID 14568445. S2CID 739665.

- ^ Bolger DJ, Perfetti CA, Schneider W (May 2005). "Cross-cultural effect on the brain revisited: universal structures plus writing system variation". Human Brain Mapping (in French). 25 (1): 92–104. doi:10.1002/hbm.20124. PMC 6871743. PMID 15846818.

- ^ Brambati SM, Ogar J, Neuhaus J, Miller BL, Gorno-Tempini ML (July 2009). "Reading disorders in primary progressive aphasia: a behavioral and neuroimaging study". Neuropsychologia. 47 (8–9): 1893–900. doi:10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2009.02.033. PMC 2734967. PMID 19428421.

- ^ a b Baddeley A, Lewis V, Vallar G (May 1984). "Exploring the Articulatory Loop". The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology Section A. 36 (2): 233–252. doi:10.1080/14640748408402157. S2CID 144313607.

- ^ a b Cowan N (February 2001). "The magical number 4 in short-term memory: a reconsideration of mental storage capacity". The Behavioral and Brain Sciences. 24 (1): 87–114, discussion 114–85. doi:10.1017/S0140525X01003922. PMID 11515286.

- ^ Caplan D, Rochon E, Waters GS (August 1992). "Articulatory and phonological determinants of word length effects in span tasks". The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology. A, Human Experimental Psychology. 45 (2): 177–92. doi:10.1080/14640749208401323. PMID 1410554. S2CID 32594562.

- ^ Waters GS, Rochon E, Caplan D (February 1992). "The role of high-level speech planning in rehearsal: Evidence from patients with apraxia of speech". Journal of Memory and Language. 31 (1): 54–73. doi:10.1016/0749-596x(92)90005-i.

- ^ Cohen L, Bachoud-Levi AC (September 1995). "The role of the output phonological buffer in the control of speech timing: a single case study". Cortex; A Journal Devoted to the Study of the Nervous System and Behavior. 31 (3): 469–86. doi:10.1016/s0010-9452(13)80060-3. PMID 8536476. S2CID 4480375.

- ^ Shallice T, Rumiati RI, Zadini A (September 2000). "The selective impairment of the phonological output buffer". Cognitive Neuropsychology. 17 (6): 517–46. doi:10.1080/02643290050110638. PMID 20945193. S2CID 14811413.

- ^ Shu H, Xiong H, Han Z, Bi Y, Bai X (2005). "The selective impairment of the phonological output buffer: evidence from a Chinese patient". Behavioural Neurology. 16 (2–3): 179–89. doi:10.1155/2005/647871. PMC 5478832. PMID 16410633.

- ^ Oberauer K (2002). "Access to information in working memory: Exploring the focus of attention". Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 28 (3): 411–421. doi:10.1037/0278-7393.28.3.411. PMID 12018494.

- ^ Unsworth N, Engle RW (January 2007). "The nature of individual differences in working memory capacity: active maintenance in primary memory and controlled search from secondary memory". Psychological Review. 114 (1): 104–32. doi:10.1037/0033-295x.114.1.104. PMID 17227183.

- ^ Barrouillet P, Camos V (December 2012). "As Time Goes By". Current Directions in Psychological Science. 21 (6): 413–419. doi:10.1177/0963721412459513. S2CID 145540189.

- ^ Bornkessel-Schlesewsky I, Schlesewsky M, Small SL, Rauschecker JP (March 2015). "Neurobiological roots of language in primate audition: common computational properties". Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 19 (3): 142–50. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2014.12.008. PMC 4348204. PMID 25600585.

- ^ Buchsbaum BR, D'Esposito M (May 2008). "The search for the phonological store: from loop to convolution". Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 20 (5): 762–78. doi:10.1162/jocn.2008.20501. PMID 18201133. S2CID 17878480.

- ^ Miller LM, Recanzone GH (April 2009). "Populations of auditory cortical neurons can accurately encode acoustic space across stimulus intensity". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 106 (14): 5931–5. Bibcode:2009PNAS..106.5931M. doi:10.1073/pnas.0901023106. PMC 2667094. PMID 19321750.

- ^ Tian B, Reser D, Durham A, Kustov A, Rauschecker JP (April 2001). "Functional specialization in rhesus monkey auditory cortex". Science. 292 (5515): 290–3. Bibcode:2001Sci...292..290T. doi:10.1126/science.1058911. PMID 11303104. S2CID 32846215.

- ^ Alain C, Arnott SR, Hevenor S, Graham S, Grady CL (October 2001). ""What" and "where" in the human auditory system". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 98 (21): 12301–6. Bibcode:2001PNAS...9812301A. doi:10.1073/pnas.211209098. PMC 59809. PMID 11572938.

- ^ De Santis L, Clarke S, Murray MM (January 2007). "Automatic and intrinsic auditory "what" and "where" processing in humans revealed by electrical neuroimaging". Cerebral Cortex. 17 (1): 9–17. doi:10.1093/cercor/bhj119. PMID 16421326.

- ^ Barrett DJ, Hall DA (August 2006). "Response preferences for "what" and "where" in human non-primary auditory cortex". NeuroImage. 32 (2): 968–77. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.03.050. PMID 16733092. S2CID 19988467.

- ^ Linden JF, Grunewald A, Andersen RA (July 1999). "Responses to auditory stimuli in macaque lateral intraparietal area. II. Behavioral modulation". Journal of Neurophysiology. 82 (1): 343–58. doi:10.1152/jn.1999.82.1.343. PMID 10400963.

- ^ Mazzoni P, Bracewell RM, Barash S, Andersen RA (March 1996). "Spatially tuned auditory responses in area LIP of macaques performing delayed memory saccades to acoustic targets". Journal of Neurophysiology. 75 (3): 1233–41. doi:10.1152/jn.1996.75.3.1233. PMID 8867131.

- ^ Lachaux JP, Jerbi K, Bertrand O, Minotti L, Hoffmann D, Schoendorff B, Kahane P (October 2007). "A blueprint for real-time functional mapping via human intracranial recordings". PLOS ONE. 2 (10): e1094. Bibcode:2007PLoSO...2.1094L. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0001094. PMC 2040217. PMID 17971857.

- ^ Jardri R, Houfflin-Debarge V, Delion P, Pruvo JP, Thomas P, Pins D (April 2012). "Assessing fetal response to maternal speech using a noninvasive functional brain imaging technique". International Journal of Developmental Neuroscience. 30 (2): 159–61. doi:10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2011.11.002. PMID 22123457. S2CID 2603226.

- ^ Poliva O (2017-09-20). "From where to what: a neuroanatomically based evolutionary model of the emergence of speech in humans". F1000Research. 4: 67. doi:10.12688/f1000research.6175.3. PMC 5600004. PMID 28928931.

- ^ Poliva O (2016-06-30). "From Mimicry to Language: A Neuroanatomically Based Evolutionary Model of the Emergence of Vocal Language". Frontiers in Neuroscience. 10: 307. doi:10.3389/fnins.2016.00307. PMC 4928493. PMID 27445676.

- ^ a b c d e Suri, Sana. "What sign language teaches us about the brain". The Conversation. Retrieved 2019-10-07.

- ^ a b c 과학적인 미국인. (2002). 뇌 속의 수화. [브로슈어. http://lcn.salk.edu/Brochure/SciAM%20ASL.pdf에서 검색됨

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Norton ES, Kovelman I, Petitto LA (March 2007). "Are There Separate Neural Systems for Spelling? New Insights into the Role of Rules and Memory in Spelling from Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging". Mind, Brain and Education. 1 (1): 48–59. doi:10.1111/j.1751-228X.2007.00005.x. PMC 2790202. PMID 20011680.

- ^ a b c d e Treiman R, Kessler B (2007). Writing Systems and Spelling Development. The Science of Reading: A Handbook. Blackwell Publishing Ltd. pp. 120–134. doi:10.1002/9780470757642.ch7. ISBN 978-0-470-75764-2.