파키스탄의 이슬람교

Islam in Pakistan 라호르의 바드샤히 모스크에서 기도하는 이드 | |

| 총인구 | |

|---|---|

| c.2억 4,250만명 (2023년 인구조사 추정)[1][2][3] (인구의 97%) | |

| 인구가 많은 지역 | |

| 파키스탄 전역 | |

| 종교 | |

| 다수파: 90%의 수니파 무슬림, 소수파: 10%의 시아파 무슬림[4] | |

| 언어들 | |

| 흔한 우르두 주, 펀자브 주, 파슈토 주, 신디 주, 사라이키 주, 발로치 주, 카슈미르 주, 브라후이 주, 힌코 주, 시나 주, 발티 주, 코와르 주, 부루샤스키 주, 코히스타니 주, 와키 주, 칼라샤 주 등입니다. |

| 파키스탄의 이슬람교 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||

| 역사 | ||||||

| 주요 인물 | ||||||

| 사상학파 | ||||||

| 법학전문대학원 | ||||||

| 모스크 | ||||||

| 정치 조직/운동 | ||||||

| 문화 | ||||||

| ||||||

| 기타주제 | ||||||

| 나라별 이슬람교 |

|---|

|

| |

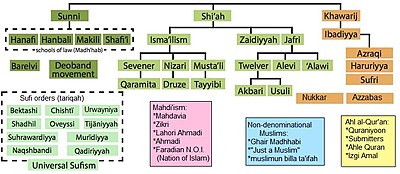

이슬람교는 파키스탄 이슬람 공화국에서 가장 크고 국교입니다. 파키스탄에는 2억 4천만 명이 넘는 이슬람 신자들이 있습니다.[7][8] 인구의 90%가 수니파 이슬람교를 따르고 있습니다. 대부분의 파키스탄 수니파 무슬림들은 하나피 법학파에 속하며, 이는 바렐비와 데오반디 전통으로 대표됩니다.

일부 추정에 따르면, 더 많은 수니파 이슬람교도들이 데오반디교보다 바렐비교를 고수합니다.[9][10] 데오반디 사상파의 추종자이기도 한 무함마드 지아울하크는 파키스탄의 이슬람화를 시도하면서 데오반디 신앙에 부합하는 수니파 정책과 법의 시행을 우선시했습니다.[10]

후사인 하카니는 파키스탄을 "정치 이슬람의 세계적 중심지"라고 불렀습니다.[11] 파키스탄 민족주의 서사는 아대륙의 무슬림들이 다른 아대륙과는 다른 그들만의 독특한 삶에 대한 관점을 가진 독립적인 국가라는 생각에 기반을 두고 있습니다.[12]

파키스탄인의 약 97%가 이슬람교도입니다.[13] 파키스탄은 인도네시아 다음으로 세계에서 두 번째로 이슬람교도가 많습니다.[14][15] The majority are Sunni (85-90%)[16][17][18][19][20] while Shias make up between 10% and 15%.[21][17][22][23][24][25] 그런데 최근 중동에서 와합비의 영향으로 한발리 학파가 인기를 끌고 있습니다.[26] 파키스탄의 소수 무슬림 인구는 코란주의자, 비민족적인 무슬림을 포함합니다.[27] 파키스탄에는 또한 마흐다비아와 아마디스라는 두 가지 마흐디주의 기반 교리가 있는데,[28] 이들 중 후자는 파키스탄 헌법에 의해 비이슬람교도로 간주되며, 이슬람 인구의 1%를 차지합니다.[29] 파키스탄은 세계에서 가장 큰 무슬림 다수 도시(카라치)를 가지고 있습니다.[30]

역사

독립전

이슬람은 예언자 무함마드의 생전에 인도 아대륙에 도달했습니다. 한 전통에 따르면, 바바 라탄 힌디어는 펀자브 출신의 상인으로 이슬람 예언자 무함마드의 아랍인이 아닌 동료 중 한 명이었습니다.[31][32] 서기 644년 라실 전투에서 신드 왕국을 물리치고 라시둔 칼리파국이 막란을 정복했습니다. Derryl N. Maclean에 따르면, 신드와 알리 또는 시아파의 초기 파르티잔 사이의 연결고리는 서기 649년에 신드를 건너 막란으로 가서 칼리프에게 이 지역에 대한 보고서를 제시한 하킴 이븐 자발라 알 압디로 거슬러 올라갈 수 있습니다.[33] 알리의 칼리프 시대에, 신드의 많은 힌두교인들은 이슬람의 영향을 받았고, 일부는 심지어 낙타 전투에 참여했습니다. 서기 712년, 젊은 아랍 장군 무함마드 빈 카심이 인더스 지역의 대부분을 정복하여 알만수라에 수도를 두고 "아스-신드" 지방이 되었습니다.[34][35][36][37][38] 파키스탄 정부의 공식 연표는 이 시기를 파키스탄의 기틀이 마련된 시기라고 주장합니다.[34][39][40] 서기 10세기 말까지 이 지역은 가즈나비족에 의해 정복된 힌두교의 샤히 왕들에 의해 지배되었습니다.

중세 초기 (642–1219 CE)는 이 지역에서 이슬람교가 확산되는 것을 목격했습니다. 이 시기에 수피 선교사들은 지역 불교와 힌두교 인구의 대부분을 이슬람교로 개종시키는 데 중추적인 역할을 했습니다.[41] 이러한 발전은 이 지역에 가즈나비드 제국(975–1187 CE), 고리드 왕국, 델리 술탄국(1206–1526 CE) 등 여러 이슬람 제국을 연속적으로 통치할 수 있는 발판을 마련했습니다. 델리 술탄국의 마지막 왕이었던 로디 왕조는 무굴 제국으로 대체되었습니다.

독립된 파키스탄에서

상태의 성질

이슬람 연맹 지도부인 울라마(이슬람 성직자)와 진나는 파키스탄에 대한 그들의 비전을 이슬람 국가의 관점에서 분명히 말했습니다.[42] 무하마드 알리 진나는 울라마와 밀접한 연관성을 가지게 되었습니다.[43] 이슬람 학자 마울라나 샤비르 아마드 우스마니는 진나가 죽자 무굴 황제 아우랑제브 다음으로 가장 위대한 이슬람교도라고 표현하며 진나의 죽음을 무함마드의 죽음에 비유하기도 했습니다.[43] 우스마니는 파키스탄인들에게 진나의 단결, 신앙, 규율의 메시지를 기억하고 그의 꿈을 이루기 위해 노력할 것을 요청했습니다.

카라치에서 앙카라, 파키스탄에서 모로코에 이르기까지 모든 이슬람 국가의 견고한 블록을 만들기 위해. 그는 세계의 이슬람교도들이 적들의 공격적인 계획에 대한 효과적인 견제로서 이슬람의 기치 아래 연합하는 것을 보고 싶었습니다.[43]

파키스탄을 이념적인 이슬람 국가로 변화시키기 위해 취한 첫 번째 공식 조치는 1949년 3월 리아콰트 알리 칸 초대 총리가 제헌 의회에서 목표 결의안을 제출했을 때였습니다.[44] 목표 결의안은 우주 전체에 대한 주권은 전능하신 하나님께 있다고 선언했습니다.[45] 무슬림 연맹의 회장인 Chaudhry Khaliquzaman은 파키스탄이 모든 이슬람 국가들을 범이슬람적인 조직인 이슬람으로 모을 것이라고 발표했습니다.[46] 칼리크는 파키스탄이 이슬람 국가일 뿐 아직 이슬람 국가는 아니지만, 이슬람의 모든 신자들을 하나의 정치 단위로 끌어들인 후에는 반드시 이슬람 국가가 될 수 있다고 믿었습니다.[47] 파키스탄 정치에 관한 최초의 학자 중 한 명인 키스 캘러드는 파키스탄이 이슬람 세계에서 목적과 전망의 본질적인 통합을 믿는다고 관찰했습니다.

파키스탄은 이슬람교도들의 대의명분을 증진시키기 위해 설립되었습니다. 다른 이슬람교도들은 동정심 있고 심지어 열정적일 것으로 기대되었을 수도 있습니다. 그러나 이것은 다른 이슬람 국가들도 종교와 국적 사이의 관계에 대해 같은 견해를 취할 것이라고 가정했습니다.[46]

하지만, 파키스탄의 범이슬람주의 정서는 그 당시 다른 이슬람 정부들에 의해 공유되지 않았습니다. 무슬림 세계의 다른 지역의 민족주의는 민족, 언어, 문화에 기반을 두고 있습니다.[46] 비록 무슬림 정부들은 파키스탄의 범이슬람적인 열망에 동조하지 않았지만, 전세계의 이슬람주의자들은 파키스탄에 끌렸습니다. 팔레스타인의 그랜드 무프티, 알하지 아민 알 후세인이니와 같은 인물들과 무슬림 형제단과 같은 이슬람 정치 운동의 지도자들이 이 나라를 자주 방문하게 되었습니다.[48] 지아울하크 장군이 군부 쿠데타로 집권한 뒤 히즈부트-타흐리르(칼리프 국가 수립을 요구하는 이슬람 단체)는 파키스탄에서 조직망과 활동을 확대했습니다. 그것의 설립자인 Taqi al-Din al-Nabhani는 JAmat-e-Islami (JI)의 설립자인 Abul A'la Maudududi와 정기적인 통신을 유지할 것이며, 그는 또한 박사에게 촉구했습니다. ISr Ahmed는 세계적인 칼리프 국가 설립을 위해 파키스탄에서 그의 일을 계속할 것입니다.[49]

사회과학자 나심 아마드 자베드(Nasim Ahmad Jawed)는 1969년 파키스탄에서 교육받은 전문가들이 사용하는 국가 정체성의 유형에 대한 설문조사를 실시했습니다. 그는 동파키스탄(현재의 방글라데시) 사람들의 60% 이상이 세속적인 국가 정체성을 가지고 있다고 공언했다는 것을 발견했습니다. 그러나 서파키스탄(현재 파키스탄)에서는 같은 인물이 세속적인 정체성이 아닌 이슬람적인 정체성을 가지고 있다고 공언했습니다. 게다가, 동파키스탄의 같은 인물은 그들의 정체성을 이슬람교가 아닌 민족적 측면에서 정의했습니다. 민족보다는 이슬람교가 더 중요하다고 말한 서파키스탄에서는 정반대였습니다.[50]

파키스탄 최초의 총선 후 1973년 헌법은 선출된 의회에 의해 만들어졌습니다.[51] 헌법은 파키스탄을 이슬람 공화국으로 선포하고 이슬람을 국교로 선포했습니다. 또한 모든 법은 코란과 순나에 규정된 이슬람교의 금지법에 따라야 하며 그러한 금지법을 거부하는 법은 제정될 수 없다고 명시했습니다.[52] 1973년 헌법은 또한 이슬람의 해석과 적용을 촉진하기 위해 샤리아트 법원과 이슬람 이념 위원회와 같은 특정 기관을 만들었습니다.[53]

자울하크의 이슬람화

1977년 7월 5일, 지아울하크 장군은 쿠데타를 일으켰습니다.[54] Zia-ul-Haq의 쿠데타 1~2년 전, 그의 전임자인 좌파 총리 Zulfikar Ali Buto는 Nizam-e-Mustafa[55] (선지자의 통치)라는 부흥주의 기치 아래 통합된 강력한 반대에 직면했습니다. 이 운동의 지지자들에 따르면, 샤리아 법에 근거한 이슬람 국가를 세우는 것은 무함마드가 이슬람교도들을 통치했던 초기 이슬람의 정의와 성공으로 돌아가는 것을 의미한다고 합니다.[56] 거리 이슬람화의 흐름을 막기 위해 부토는 또한 거리 이슬람화를 요구했고 이슬람교도들과 나이트클럽, 경마장에서 와인을 마시고 파는 것을 금지했습니다.[56][57]

"이슬람화"는 그의 정부의 "주요" 정책 [58]또는 "중심"[59]이었습니다. Zia-ul-Haq는 이슬람 국가를 세우고 샤리아 법을 시행하기 위해 헌신했습니다.[56] Zia는 이슬람 교리를 이용하여 법률 사건을 판단하기 위해 샤리아트 사법 법원과[53] 법원 벤치를[60][61] 별도로 설치했습니다.[62] 파키스탄 법에는 새로운 형사 범죄(간통, 간통, 모독, 모독)와 새로운 처벌(매질, 절단, 돌팔매질 사망)이 추가되었습니다. 은행 계좌에 대한 이자 지급은 "손익" 지급으로 대체되었습니다. 자카트 자선 기부는 연 2.5%의 세금이 되었습니다. 학교 교과서와 도서관은 비이슬람적인 자료들을 제거하기 위해 정비되었습니다.[63] 사무실, 학교 및 공장에는 기도 공간을 제공해야 했습니다.[64] 지아는 보수적인 학자들이 텔레비전의 고정자가 [62]된 반면, 울라마(이슬람 성직자)와 이슬람 정당의 영향력을 강화했습니다.[64] 자마트-이-이슬람당 소속 활동가 1만 명이 정부 직책에 임명돼 그의 사망 이후에도 그의 안건이 계속 유지될 수 있도록 했습니다.[56][62][65][66] 보수적인 울라마 (이슬람 학자들)가 이슬람 이념 위원회에 추가되었습니다.[60] 기독교와 힌두교 지도자들이 현의 정치 과정에서 소외감을 느낀다고 불평했음에도 불구하고 힌두교와 기독교인들을 위한 별도의 선거인단이 1985년에 설립되었습니다.[67]

지아의 국가는 이슬람화를 후원하여 파키스탄에서 수니파와 시아파, 데오반디스와 바렐비스 사이의 종파적 분열을 증가시켰습니다.[68] 바렐비스의 다수는 파키스탄의 건국을 지지했고,[69] 바렐비울라마 또한 1946년 선거에서 파키스탄 운동을 지지하는 지방을 발행했지만,[70][71] 아이러니하게도 파키스탄의 이슬람 국가 정치는 대부분 데오반디(그리고 나중에 아흘-에-하디스/살라피) 기관을 지지했습니다.[72] 이것은 비록 영향력이 있기는 하지만 소수의 데오반디 성직자들만이 파키스탄 운동을 지지했음에도 불구하고 그러했습니다.[72] 지아울하크는 군대와 데오반디 기관 사이에 강력한 동맹을 맺었습니다.[72] 파키스탄에서는 국가에 의해 온건한 수피파로 지목된 행위자들, 즉 데오반디스와 같은 보수적 개혁가들에 대응하여 19세기에 설립된 운동인 바렐위스가 2009년부터 파키스탄의 영혼을 서서히 '탈레반화'로부터 구하기 위해 정부의 요청에 따라 동원되었습니다.[73]

이슬람화 프로그램의 가능한 동기로는 지아의 개인적인 신앙심([74]대부분의 설명은 그가 종교 가정 출신이라는 것에 동의함), 정치적 동맹을 얻고자 하는 열망, 이슬람 국가로서 파키스탄의 근거를 "충성"하려는 열망, 그리고/또는 일부 파키스탄인들에 의해 그가 "억압적"이라고 간주되었던 것을 정당화하기 위한 정치적 필요 등이 포함되었습니다. 대표성이 없는 계엄령 체제"[75]라고 주장했습니다.

무함마드 지아울하크 장군 정부가 들어서기 전까지 파키스탄 헌법에 이슬람 율법을 집행할 '이빨'이 없어 '이슬람 운동가'들은 좌절했습니다. 예를 들어, 1956년 헌법에서 국가는 "이슬람 도덕 기준"을 강제하지 않고 강제로 만들고 성매매, 도박, 주류 소비 등을 "예방"하기 위해 "노력"했습니다. 관심은 "가능한 한 빨리" 없어지는 것이었습니다.[76][77]

샤질 자이다에 따르면 백만 명의 사람들이 자울 하크의 장례식에 참석했는데 그 이유는 그가 그들이 원하는 것, 즉 더 많은 종교를 주었기 때문이라고 합니다.[78] PEW의 여론 조사에 따르면 파키스탄의 84%는 샤리아를 이 땅의 공식 법률로 만드는 것을 선호합니다.[79] 2013년 Pew Research Center 보고서에 따르면 파키스탄 무슬림의 대다수는 이슬람교를 떠나는 사람들에 대한 사형을 지지합니다(62%). 대조적으로, 이슬람교를 떠나는 사람들에 대한 사형 지지는 파키스탄과 유산을 공유한 남아시아 무슬림 국가 방글라데시에서 36%에 불과했습니다.[80] 2010년 퓨 리서치 센터의 여론 조사에 따르면 파키스탄의 87%는 자신을 국적의 일원이 아닌 '무슬림 우선'으로 생각하는 것으로 나타났습니다. 이것은 조사된 모든 이슬람 인구 중 가장 높은 수치였습니다. 이와는 대조적으로 요르단은 67%, 이집트는 59%, 튀르키예는 51%, 인도네시아는 36%, 나이지리아는 71%만이 자신들을 자국 국적의 구성원이 아닌 '이슬람 제일주의자'로 여겼습니다.

much 또는 ulama (이슬람 성직자)와 Jamaat-e-Islami (이슬람 정당)와 같은 "이슬람 활동가"들은 "이슬람 법과 이슬람 관행"의 확대를 지지합니다. "이슬람 모더니스트"들은 이러한 확장에 미온적이며 "일부는 서구의 세속주의 노선을 따라 발전을 옹호할 수도 있습니다."[82]

이슬람적 삶의 방식

모스크는 파키스탄의 중요한 종교이자 사회 기관입니다.[83][84] 많은 의식과 의식은 이슬람 달력에 따라 거행됩니다.

교파

미국 중앙정보국(CIA) 월드 팩트북(World Factbook)과 옥스퍼드 이슬람학 센터(Oxford Center for Islam Studies)에 따르면 파키스탄 전체 인구의 95~97%가 이슬람교도입니다.[17][13]

수니파

파키스탄 무슬림의 대부분은 수니파 이슬람교에 속해 있습니다. 이슬람교도들은 Madhaib(단어: Madhaib)이라고 불리는 다양한 학교에 속해 있습니다. Madhhab), 즉 법학파(Urdu의 'Maktab-e-Fikr' (Maktab-e-Fikr). 파키스탄의 수니파 인구에 대한 추정치는 85%에서 90%[16][17][18][19][20]까지 다양합니다.

바렐비와 데오반디 수니파 무슬림

파키스탄의 두 주요 수니파 종파는 바렐비 운동과 데오반디 운동입니다. 파키스탄의 종파와 하위 종파에 대한 통계는 "tenuous"라고 불리지만,[86] 두 그룹의 규모에 대한 추정치는 파키스탄 인구의 약간의 대다수를 바렐비 학파의 추종자들에게 제공하는 반면, 15-25%는 데오반디 법학파를 따르는 것으로 생각됩니다.[87][88][89]

샤이아

시아파는 이 나라 인구의 약 10-15%를 차지하는 것으로 추정됩니다.[90] 파키스탄에서 발견되는 시아파 이슬람의 주요 전통은 상업과 산업에서 두각을 나타내는 것으로 알려진 다우디 보흐라스와 호자 이스마일리스입니다.[91]

많은 저명한 시아파 무슬림 정치인들이 파키스탄 운동 기간 동안 수십 년 동안 파키스탄을 만드는 데 결정적인 역할을 한 것으로 알려져 있습니다. 무슬림 연맹의 초대 회장이자 초기의 주요 재정 지원자로서의 역할은 믿음으로 이스마일리인 아가 칸 3세 경에 의해 수행되었습니다. 무슬림 연맹의 초기 수십 년 동안 중요한 역할을 맡았던 다른 정치인들로는 라자 사히브, 시드 아메르 알리, 시드 와지르 하산 등이 있습니다.[92]

2012년 조사에 따르면 조사 대상 파키스탄인의 50%는 이슬람교도로 시아파로 간주되고 41%는 이슬람교도로 거부했습니다.[93][94] 시아파는 1948년부터 파키스탄 정부에 의한 차별을 주장하며 수니파가 사업, 공식 직책, 사법 행정 등에서 우선권을 부여받고 있다고 주장했습니다.[95] 시아파에 대한 공격은 Zia-ul-Haq 대통령 하에서 증가했으며 [95]1983년 카라치에서 파키스탄 최초의 대규모 종파 폭동이 발생했으며 이후 다른 지역으로 확산되었습니다.[96] 시아파는 오랫동안 국내에서 라쉬카르-에-장비와 같은 수니파 급진 집단의 표적이 되어 왔습니다. 종파간 폭력은 수니파와 시아파 간의 종파간 폭력이 여러 차례 발생하면서 매년 무하람의 달에 반복되는 특징이 되었습니다.[96][97][98] 2008년 이후 수천 명의 시아파가 수니파 극단주의자들에 의해 살해되었으며, 두 종파 간의 폭력적인 충돌은 흔한 일입니다.[99]

파키스탄에서 시아파의 일부는 하자라 민족인데, 이들은 언어와 얼굴 생김새로 인해 다른 시아파와 구별됩니다. 대부분의 하자라인들은 아프가니스탄에 살고 있지만, 파키스탄에서도 65만에서 90만 명이 거주하고 있으며, 약 50만 명이 퀘타 시에 살고 있습니다.[100]

수피즘

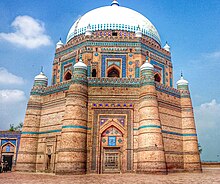

수피즘은 방대한 용어이며 철학이 강한 전통을 가진 파키스탄 내에 많은 수피교 교단이 존재합니다. 역사적으로, 수피 선교사들은 펀자브와 신드의 원주민들을 이슬람교로 개종시키는 데 중추적인 역할을 했습니다.[101] 파키스탄에서 가장 눈에 띄는 무슬림 수피 교단은 카디리야, 나크슈반디야, 치슈티야, 수하르와디야 사일라스(무슬림 교단)이며 파키스탄에는 많은 신자가 있습니다. 다르가를 방문하는 전통은 오늘날에도 여전히 행해지고 있습니다. 전국적으로 많은 관심을 받는 신사는 라호르의 데이터 간즈 바크쉬(알리 하즈웨리),[102] 쇼코트 장의 술탄 바후, 물탄의 바하우딘 자카리야,[103] 세환의 샤바즈 칼란더(12세기경),[102] 카이버 파크툰크화 주의 비트, 신드[104], 레만 바바의 샤 압둘 라티프 비타이입니다. 수피 성도들의 우르스 (사망 기념일)는 매년 신자들에 의해 거행되는 그들의 성지에 대한 가장 큰 모임을 차지합니다.

비록 인기 있는 수피 문화가 수피 음악과 춤을 특징으로 하는 신사와 매년 열리는 축제에서의 목요일 밤 모임이 중심이지만, 사르와리 카드리 교단과 같은 특정 타리카들은 그러한 전통을 자제하고 신사를 방문하고 기도를 하거나 만카바트를 암송하는 것을 믿습니다. 게다가, 현대 이슬람 근본주의자들은 또한 노래, 춤, 음악의 대중적인 전통을 비판하는데, 이것은 그들의 관점에서 모하마드와 그의 동료들의 가르침과 실천을 정확하게 반영하지 않습니다. 2010년에 64명의 사망자를 낸 5명의 수피 신사와 축제를 겨냥한 테러가 있었습니다. 현재 파키스탄에서 알려진 타리카들은 오래된 수피파의 전통에 따라 일반적으로 테스크로 알려진 조직을 유지하고 알라의 디크르를 위한 칸카를 가지고 있습니다.[105][106]

코란주의자들

쿠란주의, 쿠라니윤, 또는 아흘 쿠란으로 알려진 하디스의 권위를 거부하는 이슬람교도들도 파키스탄에 있습니다.[107] 파키스탄에서 가장 큰 코란 단체는 아흘 코란이고, 바즈메 톨루에 이슬람이 그 뒤를 이룹니다. 파키스탄의 또 다른 코란주의 운동은 Ahlu Zikr입니다.[27]

비유명적

파키스탄 무슬림의 약 12퍼센트는 스스로를 묘사하거나 비차별적인 무슬림들과 겹치는 신념을 가지고 있습니다. 이 이슬람교도들은 대다수의 이슬람교도들과 대체로 겹치며 기도의 차이는 보통 존재하지 않거나 무시할 수 있다는 믿음을 가지고 있습니다. 그럼에도 불구하고, 그들이 무슬림 신앙의 어떤 영역이나 의식과 가장 밀접하게 일치하는지에 대한 명확한 설명을 요구하는 인구 조사에서, 그들은 보통 "무슬림일 뿐"이라고 대답합니다.[108]

현대의 문제

신성모독

파키스탄의 주요 형법인 파키스탄 형법은 모든 인정된 종교에 대해 신성모독(우르두어: قانون توہین رسالت)을 처벌하여 벌금에서 사형에 이르기까지 다양한 처벌을 하고 있습니다. 파키스탄은 1980년과 1986년 사이에 영국 식민 당국이 제정한 신성모독법을 계승하여 더욱 엄중하게 만들었고, 지아울 하크 장군의 군사 정부가 이 법을 "이슬람화"하고 아흐마디 소수민족의 무슬림적 성격을 부정하기 위해 여러 조항을 추가했습니다.[109] 1974년 9월 7일 줄피카르 알리 부토 총리가 이끄는 제2차 헌법 개정을 통해 의회는 아마디 무슬림을 비이슬람교도로 선언했습니다.[110] 1986년에 그것은 아마디 무슬림들에게도 적용되는 새로운 신성모독 조항에 의해 보완되었습니다 (아마디의 박해 참조).[111][112] 2020년, 남아시아 연구를 위한 유럽 재단(EFSAS)은 "무혐의가 입증될 때까지 유죄"라는 제목의 보고서를 통해 다음과 같이 밝혔습니다. 신성모독법의 신성모독적 성격 파키스탄은 파키스탄의 법과 법체계에 광범위한 변화를 권고했습니다.[113]

변환

파키스탄의 종교적 소수자들로부터 이슬람교로의 개종이 있었습니다. 힌두교 신자였던 바바 딘 모하마드 샤이크(Baba Deen Mohammad Shaikh)는 신드(Sindh)주의 바딘(Badin)구의 마티(Matli) 출신의 이슬람 선교사로, 11만 명이 넘는 힌두교인을 이슬람교로 개종시켰다고 주장합니다.[114] 파키스탄 인권이사회는 이슬람으로 강제 개종하는 사례가 늘고 있다고 보도했습니다.[115][116] 희생자 가족들과 활동가들에 따르면, 신드 지역의 정치적이고 종교적인 지도자인 Mian Abdul Haq는 그 주 내에서 소녀들을 강제로 개종시킨 책임이 있다고 비난을 받았습니다.[117]

참고 항목

- 파키스탄의 종교의 자유

- 파키스탄 이슬람 공화국의 역사

- 남아시아의 이슬람교

- 파키스탄의 이슬람화

- 파키스탄의 종교

- 파키스탄의 종교 차별

- 파키스탄의 시아파 이슬람교

- 파키스탄의 수피즘

- 나라별 이슬람교

참고문헌

- ^ "Pakistan's population attains new mark amid economic slump". 23 May 2023.

- ^ "Headcount finalised sans third-party audit". 26 May 2018.

- ^ "POPULATION BY RELIGION" (PDF). www.pbs.gov.pk. Retrieved 2019-01-15.

- ^ "세계 무슬림 인구의 미래: 2010년부터 2013년까지의 예측" 2013년 7월 접속.

- ^ Al-Jallad, Ahmad (30 May 2011). "Polygenesis in the Arabic Dialects". Encyclopedia of Arabic Language and Linguistics. BRILL. doi:10.1163/1570-6699_eall_EALL_SIM_000030. ISBN 9789004177024.

- ^ 세계의 무슬림들: 통합과 다양성; 제1장: 종교적 소속

- ^ "Population". The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. 2021. Retrieved 2021-07-14.

238,181,034 (July 2021 est.)

- ^ "Announcement of Results of 7th Population and Housing Census-2023 'The Digital Census'" (PDF). Pakistan Bureau of Statistics (www.pbs.gov.pk). 5 August 2023. Retrieved 15 August 2023.

- ^ "Barelvi Islam shia Islam". Global Security. Retrieved 20 February 2023.

- ^ a b Hashmi, Arshi Saleem (2014). The Deobandi Madrassas in India and their elusion of Jihadi Politics: Lessons for Pakistan (PhD). Pakistan: Quaid-i-Azam University. p. 199. Archived from the original on 30 August 2022. Retrieved 16 February 2023.

- ^ Ḥaqqānī, Husain (2005). Pakistan: between mosque and military. Washington: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. p. 131. ISBN 0-87003-214-3. Retrieved 23 May 2010.

Zia ul-Haq is often identified as the person most responsible for turning Pakistan into a global center for political Islam. ...

- ^ Ahmed, Ishtiaq (27 May 2016). "The dissenters". The Friday Times.

- ^ a b "Pakistan, Islam in". Oxford Centre for Islamic Studies. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on June 18, 2013. Retrieved 2010-08-29.

Approximately 97 percent of Pakistanis are Muslim. The majority (85–90)% percent are Sunnis following the Hanafi school of Islamic law. Between (10–15)% are Shias, mostly Twelvers.

- ^ Singh, Dr. Y P (2016). Islam in India and Pakistan – A Religious History. Vij Books India Pvt Ltd. ISBN 9789385505638.

- ^ 참조: 국가별 이슬람교

- ^ a b "Country Profile: Pakistan" (PDF). Library of Congress Country Studies on Pakistan. Library of Congress. February 2005. Retrieved 2010-09-01.

Religion: The overwhelming majority of the population (96.3 percent) is Muslim, of whom approximately 85–90 percent are Sunni and 10–15 percent Shia.

- ^ a b c d "Religions". The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. 2021. Retrieved 2021-07-14.

Muslim (official) 96.5% (Sunni 85–90%, Shia 10–15%), other (includes Christian and Hindu) 3.5% (2020 est.)

- ^ a b "Mapping the Global Muslim Population: A Report on the Size and Distribution of the World's Muslim Population". Pew Research Center. October 7, 2009. Retrieved 2010-08-28.

- ^ a b Miller, Tracy, ed. (October 2009). Mapping the Global Muslim Population: A Report on the Size and Distribution of the World's Muslim Population (PDF). Pew Research Center. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-10-10. Retrieved 2010-08-28.

- ^ a b "Pakistan – International Religious Freedom Report 2008". United States Department of State. 19 September 2008. Retrieved 2010-08-28.

- ^ "Country Profile: Pakistan" (PDF). Library of Congress Country Studies on Pakistan. Library of Congress. February 2005. Retrieved 2010-09-01.

Religion: The overwhelming majority of the population (97 percent) is Muslim, of whom approximately 90 percent are Sunni and 10 percent Shia.

- ^ "Country Profile: Pakistan" (PDF). Library of Congress Country Studies on Pakistan. Library of Congress. February 2005. Retrieved 2010-09-01.

Religion: The overwhelming majority of the population (96.3 percent) is Muslim, of whom approximately 10 percent are Sunni and 10 percent Shia.

- ^ "The World's Muslims: Unity and Diversity". Pew Research Center. 9 August 2012. Retrieved 26 December 2016.

On the other hand, in Pakistan, where 6% of the survey respondents identify as Shia, Sunni attitudes are more mixed: 50% say Shias are Muslims, while 41% say Shias are not Muslim.

- ^ "Non-Fiction: Pakistan's Shia Dynamics". 10 November 2019.

- ^ "Pakistan, Islam in". Oxford Centre for Islamic Studies. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on June 18, 2013. Retrieved 2010-08-29.

Approximately 97 percent of Pakistanis are Muslims. The majority are Sunnis following the Hanafi school of Islamic law. Between 10–15 percent are Shiis, mostly Twelvers.

- ^ "Pakistan must confront Wahhabism Adrian Pabst". TheGuardian.com. 20 August 2009.

- ^ a b 돌라타바드, 세예드 알리 호세이니, 호세인 나세리 모가담, 알리 레자 아베디 사르 아시야. "쿠란 충분성 이론의 기둥, 증명 및 요구 사항과 그 비판." IJHCS(International Journal of Humanitics and Cultural Studies) ISSN 2356-5926 (2016): 2303–2319.

- ^ 셰이크, 사미라. 구자라트에서 본 아랑셉은, 시아파와 밀레니얼 세대가 무굴 주권에 도전합니다." 왕립아시아학회지 28.3(2018): 557-581.

- ^ 1998년 파키스탄 인구조사에 따르면 인구는 291,000명(0.22%)입니다. 아마드는 파키스탄에 있습니다. 그러나, 아마디야 무슬림 공동체는 1974년 이래로 인구 조사를 거부해 왔으며, 이로 인해 파키스탄의 공식적인 수치는 정확하지 않습니다. 독립 단체들은 파키스탄 아마디야 인구를 2백만에서 3백만 사이로 추정했습니다. 그러나 200만 명은 가장 많이 인용된 수치이며 국가의 약 1%에 해당합니다. 참조:

- 200만 이상:

- 300만: 국제인권연맹: 국제 진상 조사단. 파키스탄의 표현의 자유, 협회와 집회의 자유. Ausgabe 408/2, Januar 2005, S. 61 (PDF)

- 300~400만: 국제종교자유위원회: 미국 국제종교자유위원회 연례보고서. 2005, S. 130

- 4.910.000: 제임스 미나한: 무국적자 국가들의 백과사전. 전 세계의 민족 및 국가 그룹. 그린우드 프레스. Westport 2002, 52페이지

- "Pakistan: Situation of members of the Lahori Ahmadiyya Movement in Pakistan". Retrieved April 30, 2014.

- ^ Khan, Nichola (2016). Cityscapes of Violence in Karachi: Publics and Counterpublics. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780190869786.

... With a population of over 23 million Karachi is also the world's largest Muslim city, the world's seventh largest conurbation ...

- ^ Heesterman, J. C. (1989). India and Indonesia: General Perspectives. BRILL. ISBN 9004083650.

- ^ Köprülü, Mehmet Fuat (2006). Early Mystics in Turkish Literature. Psychology Press. p. 79. ISBN 978-0-415-36686-1.

- ^ M. Ishaq, "Hakim Bin Jabala – 초기 이슬람의 영웅적 성격", 파키스탄 역사학회지, 145–50, (1955년 4월).

- ^ a b "History in Chronological Order". Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Government of Pakistan. Archived from the original on 23 July 2010. Retrieved 15 January 2010.

- ^ "Figuring Qasim: How Pakistan was won". Dawn. 2012-07-19. Retrieved 19 February 2015.

- ^ "The first Pakistani?". Dawn. Retrieved 19 February 2015.

- ^ "Muhammad Bin Qasim: Predator or preacher?". Dawn. 2014-04-08. Retrieved 19 February 2015.

- ^ Paracha, Nadeem F. "Why some in Pakistan want to replace Jinnah as the founder of the country with an 8th century Arab". Scroll.in. Retrieved 2018-01-09.

- ^ Rubina Saigol (2014). "What is the most blatant lie taught through Pakistan textbooks?". Herald. Retrieved 14 August 2014.

- ^ Shazia Rafi (2015). "A case for Gandhara". Dawn. Retrieved 19 February 2015.

- ^ Ira Marvin Lapidus (2002). A history of Islamic societies. Cambridge University Press. pp. 382–384. ISBN 978-0-521-77933-3.

- ^ Dhulipala, Venkat (2015). Creating a New Medina: State Power, Islam, and the Quest for Pakistan in Late Colonial North India. Cambridge University Press. p. 497. ISBN 9781316258385.

As the book has demonstrated, local ML functionaries, (U.P.) ML leadership, Muslim modernists at Aligarh, the ulama and even Jinnah at times articulated their vision of Pakistan in terms of an Islamic state.

- ^ a b c Dhulipala, Venkat (2015). Creating a New Medina: State Power, Islam, and the Quest for Pakistan in Late Colonial North India. Cambridge University Press. p. 489. ISBN 9781316258385.

But what is undeniable is the close association he developed with the ulama, for when he died a little over a year after Pakistan was born, Maulana Shabbir Ahmad Usmani, in his funeral oration, described Jinnah as the greatest Muslim after the Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb.

- ^ Haqqani, Husain (2010). Pakistan: Between Mosque and Military. Carnegie Endowment. p. 16. ISBN 9780870032851.

- ^ Hussain, Rizwan. Pakistan. Archived from the original on November 21, 2008.

The first important result of the combined efforts of the Jamāʿat-i Islāmī and the ʿulamāʿ was the passage of the Objectives Resolution in March 1949, whose formulation reflected compromise between traditionalists and modernists. The resolution embodied "the main principles on which the constitution of Pakistan is to be based." It declared that "sovereignty over the entire universe belongs to God Almighty alone and the authority which He has delegated to the State of Pakistan through its people for being exercised within the limits prescribed by Him is a sacred trust," that "the principles of democracy, freedom, equality, tolerance and social justice, as enunciated by Islam shall be fully observed," and that "the Muslims shall be enabled to order their lives in the individual and collective spheres in accord with the teaching and requirements of Islam as set out in the Holy Qurʿan and Sunna." The Objectives Resolution has been reproduced as a preamble to the constitutions of 1956, 1962, and 1973.

{{cite book}}:work=무시됨(도움말) - ^ a b c Haqqani, Husain (2010). Pakistan: Between Mosque and Military. Carnegie Endowment. p. 18. ISBN 9780870032851.

- ^ Dhulipala, Venkat (2015). Creating a New Medina: State Power, Islam, and the Quest for Pakistan in Late Colonial North India. Cambridge University Press. p. 491. ISBN 9781316258385.

- ^ Haqqani, Husain (2010). Pakistan: Between Mosque and Military. Carnegie Endowment. p. 19. ISBN 9780870032851.

- ^ Khan, Sher Ali (12 February 2016). "Global connections: The crackdown on Hizbut Tahrir intensifies". Herald.

- ^ Cochrane, Iain (2009). The Causes of the Bangladesh War. Lulu.com. ISBN 9781445240435.

The social scientist, Nasim Ahmad Jawed has conducted a survey of nationalism in pre-divided Pakistan and identifies the links between religion, politics and nationalism in both wings of Pakistan. His findings are fascinating and go some way to explain the differing attitudes of West and East Pakistan to the relationship between Islam and Pakistani nationalism and how this affected the views of people in both wings, especially the views of the peoples of both wings towards each other. In 1969, Jawed conducted a survey on the type of national identity that was used by educated professional people. He found that just over 60% in the East wing professed to have a secular national identity. However, in the West wing, the same figure professed an Islamic and not a secular identity. Furthermore, the same figure in the East wing described their identity in terms of their ethnicity and not in terms of Islam. He found that the opposite was the case in the West wing where Islam was stated to be more important than ethnicity.

- ^ Diamantides, Marinos; Gearey, Adam (2011). Islam, Law and Identity. Routledge. p. 196. ISBN 9781136675652.

- ^ Iqbal, Khurshid (2009). The Right to Development in International Law: The Case of Pakistan. Routledge. p. 189. ISBN 9781134019991.

- ^ a b Diamantides, Marinos; Gearey, Adam (2011). Islam, Law and Identity. Routledge. p. 198. ISBN 9781136675652.

- ^ Grote, Rainer (2012). Constitutionalism in Islamic Countries: Between Upheaval and Continuity. Oxford University Press. p. 196. ISBN 9780199910168.

- ^ Nasr, Seyyed Vali Reza Nasr (1996). Mawdudi and the Making of Islamic Revivalism. New York, Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 45–6. ISBN 0195096959.

- ^ a b c d Kepel, Gilles (2002). Jihad: The Trail of Political Islam (2006 ed.). I.B.Tauris. pp. 100–101. ISBN 9781845112578. Retrieved 5 December 2014.

- ^ Michael Heng Siam-Heng, Ten Chin Liew (2010). State and Secularism: Perspectives from Asia§General Zia-ul-Haq and Patronage of Islamism. Singapore: World Scientific. p. 360. ISBN 9789814282383.

- ^ Haqqani, Husain (2005). Pakistan:Between Mosque and Military; §From Islamic Republic to Islamic State. United States: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace (July 2005). pp. 395 pages. ISBN 978-0-87003-214-1.

- ^ Jones, Owen Bennett (2002). Pakistan : eye of the storm. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. pp. 16–7. ISBN 9780300097603.

... Zia made Islam the centrepiece of his administration.

- ^ a b Double Jeopardy: Police Abuse of Women in Pakistan. Human Rights Watch. 1992. p. 19. ISBN 9781564320636. Retrieved 3 December 2014.

- ^ Haqqani, Husain (2005). Pakistan: between mosque and military. Washington D.C.: United Book Press. p. 400. ISBN 9780870032851.

- ^ a b c Wynbrandt, James (2009). A Brief History of Pakistan. Facts on File. pp. 216–7. ISBN 9780816061846.

a brief history of pakistan zia bolster ulama.

- ^ Jones, Owen Bennett (2002). Pakistan : eye of the storm. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. pp. 16–7. ISBN 9780300097603.

zia giving him a free hand to ignore internationally accepted human rights norms.

- ^ a b Paracha, Nadeem F. (3 September 2009). "Pious follies". Dawn.com. Retrieved 20 December 2014.

- ^ Jones, Owen Bennett (2002). Pakistan : eye of the storm. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. pp. 16–7. ISBN 9780300097603.

... Zia rewarded the only political party to offer him consistent support, Jamaat-e-Islami. Tens of thousands of Jamaat activists and sympathisers were given jobs in the judiciary, the civil service and other state institutions. These appointments meant Zia's Islamic agenda lived on long after he died.

- ^ Nasr, Vali (2004). "Islamization, the State and Development". In Hathaway, Robert; Lee, Wilson (eds.). ISLAMIZATION AND THE PAKISTANI ECONOMY (PDF). Woodrow Wilson International Center or Scholars. p. 95. Retrieved 30 January 2015.

General Zia became the patron of Islamization in Pakistan and for the first time in the country's history, opened the bureaucracy, the military, and various state institutions to Islamic parties

- ^ Jones, Owen Bennett (2002). Pakistan: Eye of the Storm. Yale University Press. p. 31. ISBN 0300101473. Retrieved 9 December 2014.

separate electorates for minorities in pakistan.

- ^ Talbot, Ian (1998). Pakistan, a Modern History. NY: St.Martin's Press. p. 251. ISBN 9780312216061.

The state sponsored process of Islamisation dramatically increased sectarian divisions not only between Sunnis and Shia over the issue of the 1979 Zakat Ordinance, but also between Deobandis and Barelvis.

- ^ Long, Roger D.; Singh, Gurharpal; Samad, Yunas; Talbot, Ian (2015). State and Nation-Building in Pakistan: Beyond Islam and Security. Routledge. p. 167. ISBN 9781317448204.

In the 1940s a solid majority of the Barelvis were supporters of the Pakistan Movement and played a supporting role in its final phase (1940-7), mostly under the banner of the All-India Sunni Conference which had been founded in 1925.

- ^ Cesari, Jocelyne (2014). The Awakening of Muslim Democracy: Religion, Modernity, and the State. Cambridge University Press. p. 135. ISBN 9781107513297.

For example, the Barelvi ulama supported the formation of the state of Pakistan and thought that any alliance with Hindus (such as that between the Indian National Congress and the Jamiat ulama-I-Hind [JUH]) was counterproductive.

- ^ John, Wilson (2009). Pakistan: The Struggle Within. Pearson Education India. p. 87. ISBN 9788131725047.

During the 1946 election, Barelvi Ulama issued fatwas in favour of the Muslim League.

- ^ a b c Syed, Jawad; Pio, Edwina; Kamran, Tahir; Zaidi, Abbas (2016). Faith-Based Violence and Deobandi Militancy in Pakistan. Springer. p. 379. ISBN 9781349949663.

Ironically, Islamic state politics in Pakistan was mostly in favour of Deobandi, and more recently Ahl-e Hadith/Salafi, institutions. Only a few Deobandi clerics decided to support the Pakistan Movement, but they were highly influential.

- ^ Philippon, Alix (2018-12-13). "Positive branding and soft power: The promotion of Sufism in the war on terror". Brookings. Retrieved 2021-03-30.

- ^ Haqqani, Husain (2010). Pakistan: Between Mosque and Military. Carnegie Endowment. p. 132. ISBN 9780870032851.

- ^ Talbot, Ian (1998). Pakistan, a Modern History. NY: St.Martin's Press. p. 286. ISBN 9780312216061.

- ^ 1956년 파키스탄 헌법 제25조, 제28조, 제29조, 제198조 인용

- ^ Kennedy, Charles (1996). Islamization of Laws and Economy, Case Studies on Pakistan. Institute of Policy Studies, The Islamic Foundation. pp. 84–5.

- ^ Zaidi, Shajeel (17 August 2016). "In defence of Ziaul Haq". Express Tribune.

- ^ "Chapter 1: Beliefs About Sharia". Pew Research Center's Religion & Public Life Project. 30 April 2013. Retrieved 4 December 2016.

- ^ "Majorities of Muslims in Egypt and Pakistan support the death penalty for leaving Islam". Washington Post. Retrieved 4 December 2016.

- ^ "What Do You Consider Yourself First?". Pew Research Center's Global Attitudes Project. 31 March 2010. Retrieved 4 December 2016.

- ^ Kennedy, Charles (1996). Islamization of Laws and Economy, Case Studies on Pakistan. Institute of Policy Studies, The Islamic Foundation. p. 83.

- ^ 말릭, 자말 남아시아의 이슬람교: 짧은 역사. 라이덴과 보스턴: 브릴, 2008.

- ^ Mughal, M. A. Z. (2015-05-04). "An anthropological perspective on the mosque in Pakistan" (PDF). Asian Anthropology. 14 (2): 166–181. doi:10.1080/1683478X.2015.1055543. ISSN 1683-478X. S2CID 54051524.

- ^ 라만, T. 마드라사스: 남아시아의 마드라사스에서 파키스탄의 폭력 가능성: 티칭 테러? 자말 말리크가 편집했습니다. Routledge 2008. 64쪽

- ^ Group, International Crisis (2022). A New Era of Sectarian Violence in Pakistan. International Crisis Group. pp. Page 8–Page 14. Retrieved 20 July 2023.

- ^ Curtis, Lisa; Mullick, Haider (4 May 2009). "Reviving Pakistan's Pluralist Traditions to Fight Extremism". The Heritage Foundation. Retrieved 2011-07-31.

- ^ Pike, John (5 July 2011). "Barelvi Islam". GlobalSecurity.org. Archived from the original on 8 December 2003. Retrieved 25 September 2020.

By one estimate, in Pakistan, the Shias are 18%, Ismailis 2%, Ahmediyas 2%, Barelvis 50%, Deobandis 20%, Ahle Hadith 4%, and other minorities 4%. [...] By another estimate some 15% of Pakistan's Sunni Muslims would consider themselves Deobandi, and some 60% are in the Barelvi tradition based mostly in the province of Punjab. But some 64% of the total seminaries are run by Deobandis, 25% by the Barelvis, 6% by the Ahle Hadith and 3% by various Shiite organisations.

- ^ Group, International Crisis (2022). A New Era of Sectarian Violence in Pakistan. International Crisis Group. pp. Page 8–Page 14. Retrieved 20 July 2023.

Sunni Barelvis are believed to constitute a thin majority of the population

- ^ "Chapter 5: Boundaries of Religious Identity". Pew Research Center's Religion & Public Life Project. 2012-08-09. Retrieved 2023-07-01.

- ^ "Pakistan - Islamic Assembly, Sunni & Shiʿi Sects, Wahhābī Movement Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 2023-06-26.

- ^ Fuchs, Simon Wolfgang (2019). In a Pure Muslim Land: Shi'ism between Pakistan and the Middle East. University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-1-4696-4979-5. JSTOR 10.5149/9781469649818_fuchs.

- ^ "The World's Muslims: Unity and Diversity". Pew Research Center. 9 August 2012. Retrieved 26 December 2016.

On the other hand, in Pakistan, where 2% of the survey respondents identify as Shia, Sunni attitudes are more mixed: 50% say Shias are Muslims, while 41% say they are not.

- ^ "Chapter 5: Boundaries of Religious Identity". Pew Research Center's Religion & Public Life Project. 2012-08-09. Retrieved 2023-01-01.

- ^ a b Jones, Brian H. (2010). Around Rakaposhi. Brian H Jones. ISBN 9780980810721.

Many Shias in the region feel that they have been discriminated against since 1948. They claim that the Pakistani government continually gives preferences to Sunnis in business, in official positions, and in the administration of justice...The situation deteriorated sharply during the 1980s under the presidency of the tyrannical Zia-ul Haq when there were many attacks on the Shia population.

- ^ a b Broder, Jonathan (10 November 1987). "Sectarian Strife Threatens Pakistan's Fragile Society". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved 31 December 2016.

Pakistan`s first major Shiite-Sunni riots erupted in 1983 in Karachi during the Shiite holiday of Muharram; at least 60 people were killed. More Muharram disturbances followed over the next three years, spreading to Lahore and the Baluchistan region and leaving hundreds more dead. Last July, Sunnis and Shiites, many of them armed with locally made automatic weapons, clashed in the northwestern town of Parachinar, where at least 200 died.

- ^ Jones, Brian H. (2010). Around Rakaposhi. Brian H Jones. ISBN 9780980810721.

Many Shias in the region feel that they have been discriminated against since 1948. They claim that the Pakistani government continually gives preferences to Sunnis in business, in official positions, and in the administration of justice...The situation deteriorated sharply during the 1980s under the presidency of the tyrannical Zia-ul Haq when there were many attacks on the Shia population. In one of the most notorious incidents, during May 1988 Sunni assailants destroyed Shia villages, forcing thousands of people to flee to Gilgit for refuge. Shia mosques were razed and about 100 people were killed

- ^ Taimur, Shamil (12 October 2016). "This Muharram, Gilgit gives peace a chance". Herald. Retrieved 31 December 2016.

This led to violent clashes between the two sects. In 1988, after a brief calm of nearly four days, the military regime allegedly used certain militants along with local Sunnis to 'teach a lesson' to Shias, which led to hundreds of Shias and Sunnis being killed.

- ^ "Pakistan: Rampant Killings of Shia by Extremists". Human Rights Watch. 30 June 2014. Archived from the original on 29 November 2014. Retrieved 16 November 2014.

- ^ "Pakistan. Main minorities and indigenous peoples". World Directory of Minorities and Indigenous Peoples. Retrieved 9 August 2023.

- ^ Taj Hashmi (26 June 2014). Global Jihad and America: The Hundred-Year War Beyond Iraq and Afghanistan. SAGE Publishing India. pp. 45–. ISBN 978-93-5150-426-9.

- ^ a b Blood, Peter R., ed. (1995). Pakistan: a country study (6th ed.). Washington, D.C.: Federal Research Division, Library of Congress. p. 128. ISBN 0-8444-0834-4. OCLC 32394669.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 메인: 포스트스크립트 (링크) - ^ Dawn Staff Correspondent (27 October 2017). "Urs of Bahauddin Zakariya begins in Multan". Dawn (newspaper). Retrieved 15 February 2018.

- ^ "Urs celebrations of Hazrat Shah Abdul Latif Bhitai commence". The Express Tribune. 5 November 2017. Archived from the original on 9 November 2020. Retrieved 5 March 2021.

- ^ Produced by Charlotte Buchen. "Sufism Under attack in Pakistan". The New York Times. Archived from the original (video) on May 28, 2012. Retrieved May 21, 2012.

- ^ Huma Imtiaz; Charlotte Buchen (January 6, 2011). "The Islam That Hard-Liners Hate" (blog). The New York Times. Retrieved May 21, 2012.

- ^ 알리 우스만 카스미, 쿠라니 나마즈 모스크, 프라이데이 타임즈, 2013년 2월 16일 회수

- ^ 퓨포룸 1장: 종교적 관계 검색, 2015년 3월 11일 검색

- ^ a b "What are Pakistan's blasphemy laws?". BBC News. 6 November 2014. Archived from the original on 5 April 2019. Retrieved 21 November 2014.

- ^ "CONSTITUTION (SECOND AMENDMENT) ACT, 1974". Retrieved 24 April 2017.

- ^ PPCS. 295-C, 형법(개정)법, 1986년(III of 1986)

- ^ cf 예를 들어, Kurshid Ahmad vs. The State, PLD 1992 라호르 1, para. 35

- ^ "Pak authorities should urgently reform 'draconian' blasphemy laws: European think tank". European Foundation for South Asian Studies (EFSAS). 7 April 2020. Retrieved 14 April 2020.

- ^ "100,000 conversions and counting, meet the ex-Hindu who herds souls to the Hereafter – The Express Tribune". The Express Tribune. 2012-01-23. Retrieved 2018-04-03.

- ^ United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (30 April 2013). "Refworld – USCIRF Annual Report 2013 – Countries of Particular Concern: Pakistan". Refworld. Retrieved May 5, 2015.

- ^ "Pakistan: Religious conversion, including treatment of converts and forced conversions (2009–2012)" (PDF). Responses to Information Requests. Government Research Directorate, Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada. January 14, 2013. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 4, 2017. Retrieved January 17, 2018.

- ^ "Forced conversions, marriages spike in Pakistan".

더보기

이 문서는 공용 도메인에 있는 이 소스의 텍스트를 통합합니다.

이 문서는 공용 도메인에 있는 이 소스의 텍스트를 통합합니다.- 라자, 마수드 아쉬라프 파키스탄 구성: 건국 텍스트와 무슬림 국가 정체성의 대두, 1857–1947, 옥스포드 2010, ISBN 978-019-547811-2

- 자만, 무함마드 카심. 파키스탄의 이슬람: 역사 (Princeton UP, 2018) 온라인 리뷰