원 타임 스퀘어

One Times Square| 원 타임 스퀘어 | |

|---|---|

간판을 고려할 때 건물은 거의 보이지 않습니다. 새해 볼 드롭을 위한 탑의 기둥은 중간에서 볼 수 있습니다. | |

| |

| 일반정보 | |

| 위치 | 1 타임스퀘어 뉴욕 맨하탄 10036 |

| 좌표 | 40°45'23 ″N 73°59'11 ″W / 40.756421°N 73.9864883°W |

| 공사시작 | 1903; 전 1903) |

| 완료된 | 1904; 전1904) |

| 오프닝 | 1905년 1월 1일, |

| 주인 | 제임스타운 L.P.와 셔우드 에쿼티 |

| 높이 | |

| 안테나 첨탑 | 417 ft (127 m) |

| 지붕 | 363 ft (111 m) |

| 기술적 세부사항 | |

| 층수 | 25 |

| 바닥면적 | 110,599 sq ft (10,275.0 m2) |

| 설계 및 시공 | |

| 건축가 | 사이러스 L. W. 아이들리츠와 앤드류 C. 맥켄지 |

| 개발자 | 뉴욕 타임즈 |

| 참고문헌 | |

| [1][2][3] | |

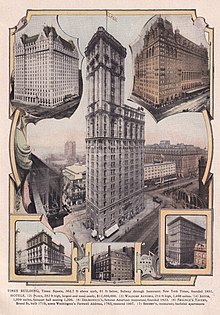

원 타임스 스퀘어(1475 브로드웨이, 뉴욕 타임스 빌딩, 뉴욕 타임스 타워, 연합 케미컬 타워 또는 단순히 타임스 타워라고도 함)는 뉴욕 맨해튼 미드타운 지역의 타임 스퀘어에 있는 25층 높이의 111m의 마천루입니다. 사이러스 L. W. 아이들리츠(Cyrus L. W. Eidlitz)가 신고딕 양식으로 디자인한 이 타워는 1903-1904년에 뉴욕 타임즈의 본사로 지어졌습니다. 그것은 7번가, 42번가, 브로드웨이, 43번가와 경계를 이루는 도시 블록을 차지합니다. 건물의 디자인은 수년 동안 크게 수정되었으며 그 이후로 모든 원래 건축 세부 사항이 제거되었습니다. 원 타임스 스퀘어의 주요 디자인 특징은 1990년대에 추가된 전면의 광고 광고판입니다. 간판에서 발생하는 막대한 수익 때문에 원 타임스퀘어는 세계에서 가장 가치 있는 광고 장소 중 하나입니다.

그 탑이 건설되는 동안 주변의 롱에이커 광장 지역은 "타임즈 스퀘어"로 이름이 바뀌었고, 뉴욕 타임즈는 1905년 1월에 그 탑으로 이사했습니다. 타워를 빠르게 확장한 후, 8년 후, 신문사의 사무실과 인쇄기는 인근의 웨스트 43번가 229번지로 이전했습니다. 원 타임 스퀘어는 매년 열리는 새해 전야 "볼 드롭" 축제와 1928년 거리 근처에 불이 켜진 대형 뉴스 티커의 도입으로 인해 이 지역의 주요 중심지로 남아 있었습니다. 타임즈는 1961년에 더글러스 리에게 이 건물을 팔았습니다. 그 후 얼라이드 케미칼은 1963년에 이 건물을 매입하여 쇼룸으로 개조했습니다. 알렉스 엠. 파커는 1973년 10월에 건물 전체를 장기 임대하여 2년 후에 구입했습니다. 원 타임스 스퀘어는 1980년대에 여러 번 매각되어 사무실 건물 역할을 계속했습니다.

금융 회사인 리먼 브라더스는 1995년에 이 건물을 인수하여 타임스퀘어 내의 주요 위치를 활용하기 위해 광고판을 추가했습니다. 제임스타운 L.P.는 1997년부터 이 건물을 소유하고 있습니다. 2017년 원 타임스퀘어 재개발의 일환으로 새로운 타임스퀘어 박물관, 전망대, 그리고 타임스퀘어-42번가 지하철역의 새로운 입구를 건설할 계획이 발표되었습니다. 제임스타운은 2022년에 5억 달러의 건물 개보수를 시작했습니다.

위치

원 타임 스퀘어는 뉴욕시의 맨해튼 미드타운 근처에 있는 타임 스퀘어의 남쪽 끝에 있습니다. 서쪽으로는 7번가, 남쪽으로는 42번가, 동쪽으로는 브로드웨이, 북쪽으로는 43번가와 경계를 이루는 도시 블록을 차지합니다.[4][5] 대지는 사다리꼴이며 5,400 평방 피트(500m2)에 달합니다.[4] 전면 블록 부지는 서쪽으로 137.84피트(42.01m), 남쪽으로 58.33피트(18m), 동쪽으로 143피트(44m), 북쪽으로 20피트(6.1m)의 전방을 가지고 있습니다.[6][7] 이 장소의 모양은 맨해튼 거리 그리드에 대한 브로드웨이의 대각선 정렬에서 비롯됩니다.[8][a] 이 건물의 주소는 원래 브로드웨이 1475번지였으나 1966년에 타임스퀘어 1번지로 변경되었습니다.[9] 현재 주소는 뉴욕시 정부가 부여한 허영심 주소입니다. 타임스퀘어 주변의 주소는 특정 순서로 할당되지 않습니다. 예를 들어, 2 타임스퀘어는 1 타임스퀘어에서 몇 블록 떨어져 있습니다.[10]

인근 건물에는 북쪽으로 1501개의 브로드웨이, 북동쪽으로 1500개의 브로드웨이, 동쪽으로 4개의 타임스퀘어, 남동쪽으로 더 니커보커 호텔, 남쪽으로 타임스퀘어 타워, 남서쪽으로 5개의 타임스퀘어, 서쪽으로 3개의 타임스퀘어가 있습니다.[4][5] 1, 2, 3, 7, <7>, N, Q, R, W, S 열차가 운행하는 뉴욕 지하철의 타임스퀘어-42번가 역 입구는 건물과 바로 인접해 있습니다. 42번가-브라이언트 파크/5번가 역에도 출입구가 있으며, 동쪽으로 한 블록도 안 되는 7, <7>, B, D, F, <F>, M 열차가 운행됩니다.[11]

현재의 원 타임스 스퀘어가 건설되기 전에 이 부지의 북쪽 끝은 Amos R의 사유지의 일부였습니다. 1901년에 Subway Realty Company에 그 부지를 매각했던 Eno.[12] 남쪽 끝에는 찰스 톨리(Charles Thorley)로부터 임대된 땅에 지어진 [13]팹스트 호텔(Pabst Hotel)이 있었습니다.[14] 그 건물의 남동쪽 모퉁이에는 원래 톨리의 이름이 들어있는 명판이 있었습니다. 왜냐하면 그는 그의 이름을 그 부지에 건설된 모든 건물에 배치할 것을 요구했기 때문입니다.[15][16] 뉴욕 타임즈 컴퍼니는 톨리가 죽은 지 4년 후인 1927년에 그 장소를 구입했지만, 명판은 1963년까지 남아있었습니다.[15]

역사

타임즈 소유권

신문 출판업자 아돌프 오크는 1896년에 뉴욕 타임즈를 구입했습니다.[17] 그 후 이 신문은 뉴욕의 신문 가에 있는 로어 맨하탄의 41 파크 가에 본사를 두었습니다. Times는 Ochs의 지도하에 크게 확장되어 Longacre Square에 새로운 본부를 위한 토지를 취득하게 되었습니다.[18][19] 1902년 8월, Ochs는 서브웨이 부동산 회사로부터 이전의 에노 그라운드를 구입했고, 패브스트 호텔 아래의 그라운드에서 찰스 톨리로부터 장기 임대를 얻었습니다.[13][20] 당시 이 부지를 통해 뉴욕 지하철 1호선이 건설되면서 주변 지역의 상업적 성장에 박차를 가하고 있었습니다.[21] 타임스는 롱에이커 광장으로 이전하기로 결정하면서 뉴욕 지하철의 타임스퀘어 역이 새 건물과 바로 인접해 있어 신문의 발행부수를 늘릴 수 있다는 점을 이유로 들었습니다.[13][22]

본부

1902년 중반, 타임즈는 롱에이커 광장에 초고층 빌딩을 지을 계획을 세우기 위해 건축가 사이러스 L. W. 아이들리츠를 고용했습니다.[22][23] 1902년 12월에 사이트 정리가 시작되어 두 달 안에 완료되었습니다. 그 후, 1903년 중반부터 노동자들이 건물의 콘크리트, 벽돌, 철공을 건설하기 시작했습니다.[23] 연말까지 철골은 일주일에 3층씩 건설되고 있었습니다.[24] Ochs의 11살 딸 Iphigene Bertha Ochs는 철골이 완성된 후 1904년 1월 18일 이 건물의 초석을 놓았습니다.[25][26] Ochs는 성공적으로 뉴욕시 올더멘 위원회를 설득하여 신문의 이름을 따서 주변 지역의 이름을 바꾸었고, Longacre Square는 1904년 4월에 Times Square로 이름을 바꾸었습니다.[27] 작업자들은 다음 달까지 인테리어 마감재를 설치하고 있었습니다.[23] 그해 8월 17개 노동조합이 파업에 들어가면서 공사가 일시 중단됐습니다.[28][29] 타임스에 따르면, 이 건물의 완공은 프로젝트 기간 동안의 다양한 파업과 궂은 날씨 때문에 299일이나 지연되었습니다.[30]

건물이 완공되기 전인 1904년 11월, 타임즈지는 1904년 미국 대통령 선거 결과를 전시하기 위해 전면에 서치라이트를 사용했습니다. 타임스는 건물 양쪽에 있는 탐조등을 점멸함으로써 어느 후보가 이겼는지를 나타냈습니다.[31] 뉴욕 타임즈는 1905년 1월 1일에 공식적으로 이 건물로 이사했습니다.[32] 새로운 본부를 홍보하는 것을 돕기 위해, 타임즈는 1904년 12월 31일 자정에 건물의 지붕에서 불꽃놀이가 시작되며 1905년을 맞이하는 새해 전야 행사를 열었습니다.[33][34][35] 이 행사는 20만 명의 관객을 끌어 모으며 성공적이었고, 1907년까지 매년 반복되었습니다.[34][35] 헤게먼 앤 컴퍼니는 1905년 중반에 대부분의 지상층을 임대하여 그 공간 내에 약국을 열었습니다.[36] 같은 해, 이 신문은 뉴스 게시판을 보여주면서 건물 북쪽에 스테레오폰 기계를 작동시키기 시작했습니다.[37] 게다가, 타임즈지는 1907년 탑 꼭대기에 음악과 전화 메시지를 전송하는 실험을 했습니다.[38]

1908년, Ochs는 불꽃놀이를 자정에 불이 붙은 공을 건물의 깃대 아래로 내리는 것으로 대체했고, 하루 중 특정한 시간을 나타내기 위해 타임볼의 사용을 패턴화했습니다.[35][39][40] 그때까지, 뉴욕시 정부는 군중 바로 위에서 터뜨려 위험을 초래한 불꽃놀이를 금지했습니다.[41] "볼 드롭"은 맨하탄 하부에 있는 웨스턴 유니언 텔레그래프 빌딩 꼭대기에 있는 타임볼에서 직접 영감을 얻었습니다.[42] 그때까지, 타임스퀘어는 새해 축하 행사를 위한 인기 있는 장소가 되었습니다.[43] 볼 드롭은 여전히 원 타임 스퀘어에서 개최되고 있으며, 매년 평균 백만 명의 관중을 끌어 모으고 있습니다.[35][39][40] 타임 타워는 전신 실험에도 사용되었으며,[44] 1908년 미국 대통령 선거를 포함한 선거 결과를 계속해서 보여주었습니다.[45] 그 건물의 지붕은 타임 타워를 뉴욕시의 고층 건물 중 "가장 대담한 것 중 하나"라고 불렀던 프랑스 작가 피에르 로티와 [46]술루의 술탄 자말룰 키람 2세와 같은 방문객들을 끌어 모았습니다.[47]

시간 재배치 및 사무실 사용

타임스 타워 부지에는 공간이 너무 적어 기계적인 지하층이 20m(65피트)나 내려가야 했습니다. 1910년대 초까지 타임스퀘어 지역은 식당, 극장, 호텔, 사무실 건물들로 빽빽하게 개발되었습니다.[48] 공간이 부족함에도 불구하고, 타임즈 책자는 "타임즈가 타임스퀘어를 떠나야 한다고 제안하는 사람은 아무도 생각하지 못했습니다."[19][49]라고 말했습니다. 1913년 2월 2일, 원 타임스 스퀘어로 이전한 지 8년 만에,[50] 타임즈는 회사 본사를 웨스트 43번가 229번지로 [39][40]이전하여 2007년까지 그곳에 머물렀습니다.[51] 출판과 구독 부문을 제외한 타임즈의 대부분의 운영은 빠르게 별관으로 옮겨갔습니다.[19] 타임스는 타임스 타워의 소유권을 유지하고 이전 공간을 그곳에 임대했습니다.[52][53][54] 이 건물은 반세기 동안 계속해서 타임스 타워로 대중적으로 알려졌습니다.[55]

원래 타임스 타워 위에 있던 타임 스퀘어 볼은 1919년에서 1920년 사이의 신년 행사 이후 교체되었습니다.[34] 1928년 9월, 타임 타워의 지붕 위에 네온 비콘이 설치되었습니다.[56] 구어체로 "지퍼"로 알려진 전기 기계식 모토그래프 뉴스 게시판 뉴스 티커는 설치 8주 [57][58]후인 1928년 11월 6일에 건물의 바닥 근처에서 운영되기 시작했습니다.[59] 그 지퍼는 원래 14,800개의 전구로 구성되어 있었고, 디스플레이는 건물 내부의 체인 컨베이어 시스템에 의해 제어되었습니다; 각각의 글자 요소(이동식 형태)는 뉴스 헤드라인을 설명하기 위해 프레임에 로드되었습니다. 프레임이 컨베이어를 따라 이동하면서 문자 자체가 외부 전구를 밝히는 전기 접촉을 유발했습니다(지퍼는 나중에 현대 LED 기술을 사용하도록 업그레이드되었습니다).[57][60][61] 지퍼에 표시된 첫 번째 헤드라인은 허버트 후버가 그날 대통령 선거에서 승리했음을 알렸습니다.[53][57] 지퍼는 그 시대의 다른 주요 뉴스 헤드라인을 표시하는 데 사용되었고, 그 내용은 나중에 스포츠와 날씨 업데이트를 포함하도록 확장되었습니다.[53][61]

1940년대에 이 건물의 지하에는 43번가 라이플 클럽이 사용하던 사격장이 있었습니다.[57] 1942년 5월, 제2차 세계 대전 중에 내려진 제한 때문에 타임 타워의 지퍼가 작동하지 않게 되었고, 이는 설치 이후 처음으로 지퍼가 작동하지 않게 된 것입니다.[62] 같은 이유로 타워의 조명이 어두워졌습니다. 결과적으로 1942년 뉴욕 주 선거는 1904년 이후 처음으로 타워의 불빛이 선거 결과를 방송하지 않았습니다.[63] 타임즈는 1943년 10월에 이 건물의 지퍼를 다시 작동시켰지만,[64][65] 2주가 채 지나지 않아 전기 사용량을 줄이기 위해 이 표지판을 다시 비활성화시켰습니다.[65][66] 이 표지판은 제2차 세계 대전이 끝날 때까지 간헐적으로 작동하다가 다시 계속 작동했습니다.[59] 1945년 8월 14일 저녁, 그 건물의 지퍼는 타임스퀘어의 만원 관중들에게 일본의 제2차 세계대전 항복을 알렸습니다.[67][68]

타임스는 1952년 미국 대선을 앞두고 지난 4일 북쪽 정면 11층에 85피트(26m) 높이의 전광판을 임시로 설치해 각 후보의 선거 개표 상황을 보여줬습니다.[69] 이 표지판은 1956년 미국 대통령 선거 동안 타임즈 타워에 다시 설치되었습니다.[70] 타워의 공은 1954-1955년 기념식 이후 교체되기도 했습니다.[34] 뉴욕 커뮤니티 트러스트는 1957년 건물 외부에 명판을 설치하여 이 명판을 관심 지점이자 비공식적인 "랜드마크"로 지정했습니다.[71]

리와 연합 화학 소유권

타임즈는 1961년에 이 건물을 광고회사의 경영 간부이자 간판 디자이너인 더글러스 리에게 팔았습니다.[16][72] 월스트리트 저널에 따르면, 리는 성공하기 전에 25년 동안 타임 타워를 구입하려고 시도했습니다.[73] 당시 건물에는 110명의 세입자가 있었고, 타임스는 지상에 있는 기밀 광고 사무실과 지퍼만 운영했습니다. Leigh는 건물 안에 전시장을 지을 계획을 세웠습니다.[16][72] 1961년 11월, 타임스 타워 지하층에서 화재가 발생하여 3명이 사망하고 24명이 부상을 입었습니다.[74] 조사관들은 나중에 화재가 " 부주의한 흡연"으로 인해 발생한 것으로 판단했습니다.[75] 1962년 12월 뉴욕시 신문 파업으로 인해 건물의 지퍼가 비활성화되었고, 2년 이상 작동하지 않았습니다.[76]

Leigh는 1963년 4월 건물을 Allied Chemical에 매각했고, Allied Chemical은 건물을 개조하여 판매 본부와 쇼룸으로 사용할 계획이었습니다.[73][77] 처음 3개 층은 유리로 다시 덮고 나일론 제품의 쇼룸 역할을 하며 내부가 완전히 정비됩니다.[77][78] 건축 회사 스미스 헤인즈 룬드버그 웨일러의 벤자민 베일린이 이 개조를 디자인했습니다.[79] 최근 뉴욕시 구역법이 변경되면서 타임스 타워를 철거하는 것보다 보수하는 것이 경제적으로 더 효율적이었습니다. 왜냐하면 부지에 새로 짓는 건물이 그렇게 높을 수 없었기 때문입니다.[80] 1963년 10월에 작업이 시작되었고,[81][82] 1964년 3월에 열린 기념식에서 타임스 타워의 원래 주춧돌은 봉인이 해제되었습니다.[83] Allied Chemical은 건물을 철골로 뜯어내고 [84]복잡한 화강암과 테라코타 정면을 대리석 패널로 교체했습니다.[85] 1964년 8월, 새로운 전면의 첫 번째 패널이 설치되는 동안 땅에 떨어졌습니다.[86] 이러한 수정은 뉴욕시 랜드마크 보존 위원회가 건물을 공식 랜드마크로 보호하는 권한을 얻기 1년 전에 이루어졌으며, 건축 평론가인 Ada Louise Huxtable은 보수에 반대하는 의견을 표명했습니다.[87] 헉스타블은 이 건물이 "풍부한 구조적 세부 사항"으로 가득 차 있다며 "급진적인 동시에 보수적"이라고 극찬했습니다.[84]

Allied Chemical은 1965년[76] 3월 Life 잡지와의 합작의 일환으로 건물 전면의 뉴스 지퍼를 다시 작동시켰습니다.[88] Allied Chemical은 1965년 7월에 탑 꼭대기에 있는 4개의 39피트(12m) 높이의 전광판을 켰다.[89] 타임즈 타워는 그 해 12월에 공식적으로 연합 화학 타워로 다시 헌정되었습니다.[90][91] 수리가 끝난 직후 얼라이드 케미칼의 나일론 사업부는 공간을 다 써버렸고, 건물의 엘리베이터 서비스도 신뢰할 수 없었던 것으로 알려졌습니다.[92] 스터퍼 푸드 코퍼레이션은 15층과 16층에도 영어를 테마로 한 식당을 운영하기로 합의했습니다.[93] Act I로 알려진 이 식당은 1966년에 문을 열었습니다.[94] 미국 우정국은 1966년 9월 공식적으로 이 건물의 주소를 브로드웨이 1475번지에서 타임스퀘어 1번지로 변경했습니다.[9]

Allied Chemical은 1972년 말에 1 Times Square를 판매하기로 했다고 발표했습니다.[95][96] 그 무렵, 회사는 더 이상 이름과 같은 타워에 여유 공간이 필요하지 않았습니다. Allied Chemical은 1972년 초에 다른 노동자들을 뉴저지의 Morris Township으로 이주시켰으며, 근처의 1411 브로드웨이에 있는 더 작은 공간으로 나일론 사업부를 이전할 계획이었습니다.[96] 그 회사는 최소 700만 달러의 가격으로 건물을 즉시 판매하기를 원했습니다.[96][97] 건물 매입 입찰서를 제출한 사람이 있는지는 알 수 없지만 얼라이드 케미칼은 결국 매각에 실패했습니다.[97]

파커 리노베이션

알렉스 엠. 파커는 1973년 10월 건물 전체를 장기 임대하고 건물을 구입할 수 있는 옵션을 선택했습니다.[97][98] 그 후 파커는 건물 이름을 엑스포 아메리카로 바꿨습니다.[99] 그는 이 건물의 17개의 이야기를 전시장으로 개조하는 동시에 1막 식당도 계속 운영할 계획이었습니다.[97] 건물을 구입한 직후 파커는 "엑스포 아메리카가 만들어낸 활동과 흥분이 주변 지역을 통해 바깥으로 흘러나와 다른 사람들이 타임스퀘어를 다시 한번 훌륭한 지역으로 만들기 위한 노력에 동참하도록 격려하는 것이 저의 희망입니다."[99]라고 말했습니다. 1974년 초, 파커는 이 건물의 지퍼에 광고와 좋은 소식만 표시할 것이라고 발표했습니다. 왜냐하면 "저는 나쁜 소식으로 그것을 겪었기 때문입니다."[100] 파커에 의하면, 그 지퍼를 작동시키는 데 일년에 10만 달러가 들었다고 합니다.[100] 로이터 통신은 지퍼의 헤드라인을 제공했습니다.[101]

파커는 1975년에[101] 625만 달러를 들여 이 건물을 살 수 있는 선택권을 행사했습니다.[102][103][104] 그리고 나서 그는 Gwathmey Siegel & Associates Architects의 건축 회사를 고용하여 유리 정면과 경사진 지붕으로 탑을 재설계했습니다.[80][101][105] 파커의 계획에 따르면, 탑에 4층이 추가될 것이고, 정면은 일방통행 유리 패널로 대체될 것입니다.[106] 파커는 또한 이 건물의 새로운 이름을 선정하기 위한 대회를 개최할 계획이었습니다.[101][105] 이 계획은 실행된 적이 없습니다.[80] 대신 파커와 에이브러햄 비메 시장은 1976년 3월 2일 원 타임스 스퀘어를 전시장으로 공식 재개장했습니다.[107] Spectacolor Inc.는 그 해 말에 건물 전면에 새로운 지퍼를 설치했습니다.[80][108] 지퍼는 짧은 시간 동안만 작동하다가 1977년에 완전히 비활성화되었습니다.[67][103][109]

타임스퀘어 재개발

초기계획

42번가 주식회사 시는 1979년 타임스퀘어 근처 웨스트 42번가 구역을 재개발하는 계획의 일환으로 원 타임스퀘어를 철거할 것을 제안했습니다.[110][111] 이 제안에 대해 상담을 받지 못한 파커는 "외설"이라며 반대 의사를 밝혔습니다.[110] 1981년에 발표된 이 부지에 대한 또 다른 계획은 원 타임스 스퀘어를 밝게 빛나는 정면을 가진 "잠재적인 시민 조각"으로 개조할 것을 요구했습니다.[112] 1981년 6월, 건축 회사인 쿠퍼 엑스투트는 엠파이어 스테이트 디벨롭먼트 코퍼레이션(ESDC)에 제출한 계획에서 원 타임스 스퀘어의 북쪽 구역 높이를 두 배로 늘릴 것을 제안했습니다.[113] 파커는 1981년 2월 이 건물을 스위스 투자 그룹 케메코드에 매각했습니다.[114] 케메코드는 그 탑을 로렌스 1세가 이끄는 투자 그룹인 TSNY Realty Corporation에 팔았습니다. 링크스맨, 1982년에 1,200만 달러에.[104] 링크스만은 북쪽 면을 사이니지 디스플레이에 사용할 수 있는 가능성을 포함하여 건물의 추가적인 개조를 약속했습니다.[102][103][104]

1983년, 42번가 재개발 프로젝트의 일환으로, 건축가 필립 존슨과 존 버지는 원 타임스 스퀘어를 폭파하고 그 장소를 바로 둘러싸는 4개의 새로운[b] 타워를 건설할 계획이었습니다.[114][115] 이 타워들의 개발자로 지정되었던 파크 타워 리얼티는 1983년 11월에 이 건물을 매입하겠다고 제안했습니다. 파크 타워는 건물을 철거하고 타임스퀘어 볼을 4개의 새로운 건물 중 가장 높은 곳으로 이전할 계획이었습니다.[116] 한 달 뒤 TSNY는 박타워를 상대로 철거를 막아달라고 소송을 냈습니다.[114][117] 앨런 J. 라일리(Allan J. Riley)는 1984년에 1,650만 달러에 건물을 인수했는데, 그 시점에 건물이 거의 임대되었습니다.[118] 또한 1984년, 시립 예술 협회는 15개국에서 1,380명 이상의 참가자들을 끌어 모으면서 그 부지를 위한 건축 디자인 대회를 열었습니다.[119] 그 해 12월, 건물주는 ESDC의 부지 규탄 계획에 반대했습니다.[120] 뉴욕 시와 주 정부는 1985년 원 타임스 스퀘어의 미래를 논의하기 위해 6명으로 구성된 위원회를 만들었습니다.[121]

이스라엘과 칼멘슨의 소유권

스티븐 엠. 이스라엘과 게리 칼멘슨은 1985년 12월에 이[122] 건물에 1,810만 달러를 지불하고 다음 달에 지역 신문인 뉴스데이에 이 건물의 표를 임대했습니다.[88][123] 이 티커는 매일 오전 6시부터 자정까지 헤드라인, 광고 및 날씨를 표시했습니다.[88] 이스라엘은 아래층 12,000 평방 피트 (12,100 미터)를 페르난도 윌리엄스 어소시에이츠가 디자인한 소매 단지인 크로스로드 패션 센터로 개조하기 시작했습니다.[124] 그때쯤, 파크 타워는 원 타임스 스퀘어를 "가운데로 올라가는 열린 계단과 그 밑부분에 거친 돌 위를 달리는 폭포"를 포함하는 7층 건물로 대체하는 계획을 추진하기 시작했습니다.[125] 시와 주 공무원들은 몇 년 전부터 비난 여론을 통해 원 타임스 스퀘어를 인수할지 여부를 논의했지만 합의에 이르지 못하고 1988년 이 계획들을 취소했습니다.[126]

1988년에 이스라엘은 처음 두 개의 층을 백만 달러에 개조했습니다. 또한 11층을 건물 입주자들을 위한 편의시설로 개조했고, 그 공간에는 생산실, 응접실, 선별실이 있었습니다.[127] 당시 이 건물은 원 타임스 스퀘어 플라자로 알려져 있었습니다.[10] 이스라엘과 칼멘슨은 1989년 프랑스 은행 Banque Arabe Internationale d'Investisement(BAII)로부터 3천만 달러를 대출받아 건물을 재융자했고, Cofat & Partners는 이 건물의 지분을 매입했습니다.[122] 그때까지 지퍼는 수익성이 있었고, 이스라엘은 "우리는 사용하라고 소리치는 빈 외벽을 가지고 있습니다."라고 말하도록 이끌었습니다.[128] 건물주들은 뉴스데이에 건물의 광고 공간을 추가로 임대하기로 협상했지만 거래가 취소됐습니다.[129] 소니는 1990년 타워 외부에 점보트론을 운영하기로 합의했고,[130][131] 1994년 3월 점보트론을 업그레이드했습니다.[132]

BAI는 1991년에 부동산을 압류하기로 결정했고, 이스라엘과 칼멘슨은 1992년 3월에 파산 보호를 신청했습니다.[133][129] 당시 건물에는 41명의 세입자가 있었지만 절반이 비어 있었습니다.[133] 이스라엘은 건물이 압류될 경우 2백만 달러의 세금을 부담하게 되므로 압류를 피하기를 원했습니다.[134] 레베카 로슨은 파산한 재산의 수취인으로 지명되었습니다.[67] 이스라엘은 1993년 압류를 피하기 위해 건물의 첫 번째 모기지를 축소할 것을 제안했지만, BAI는 이 계획에 반대했습니다.[122] 뉴스데이는 1994년 12월 31일에 건물의 티커 운영을 중단하고 임대 계약 갱신을 거부했습니다. 재정적으로 "그 신호에서 크게 벗어나지 않았다"고 믿었습니다.[67][103][109] 출판사 Pearson PLC는 뉴스데이의 임대 만료 3일 [135][136]전에 자사 제품의 뉴스, 공지, 광고에 지퍼를 사용하여 지퍼를 작동시키기로 동의했습니다.[137]

리먼 브라더스 소유권

1995년 1월, BNP(Banque National de Paris)는 이 건물을 압류 경매에서 2,520만 달러에 구입했습니다.[138] 얼마 지나지 않아 금융 서비스 회사인 리먼 브라더스는 이 건물을 2,750만 달러에 인수했습니다.[139][140] 타임즈에 따르면, 리먼 브라더스는 그 가격에 그 건물을 샀기 때문에 "비방"을 당했습니다.[139] Pearson PLC의 자회사인 Madame Tussauds는 One Times Square에 박물관을 위한 공간을 임대하려고 했으나 새 소유자와 합의에 이르지 못했습니다.[140][141] 리먼 브러더스는 타워가 너무 작기 때문에 사무실 건물로 사용하는 것이 경제적으로 비효율적일 것이라고 생각하여 타워를 광고를 위한 장소로 마케팅하기로 결정했습니다. 티커 위에 있는 원 타임스 스퀘어의 전체 외관은 광고판 표지판을 설치하기 위한 그리드 프레임을 추가하도록 수정되었습니다.[142][143][144] 다우존스앤컴퍼니는 1995년 [145][146]6월부터 지퍼를 운영하기 시작했고, 다우존스는 1997년 중반에 지퍼를 교체하면서 낡은 지퍼의 일부를 뉴욕시립박물관에 기증했습니다.[147]

소니의 점보트론은 1996년까지 운영되었습니다. 광고와 뉴스에 사용되는 것과 함께, 또한 데이비드 레터맨과 함께하는 심야 토크쇼 레이트 쇼의 제작자들에 의해 자주 사용되었는데, 그들은 스튜디오의 라이브 피드를 화면에 표시할 수도 있었습니다. 소니는 비용 절감을 위한 조치로 이 공간의 임대 갱신을 거부했고, 이후 1996년 6월 점보트론을 철거하게 되었습니다. 레이트 쇼가 자주 사용하기 때문에, 프로듀서 롭 버넷은 점보트론의 제거를 "뉴욕에게 슬프고 슬픈 날"로 농담 삼아 생각했습니다.[148] 마지막 사무실 세입자들은 1996년에 건물에서 이사를 왔고,[139] 같은 해에 첫 번째 전광판이 설치되었습니다.[149] 1996년 10월 워너 브라더스는 건물을 임대하고 기지에 소매점을 운영하기로 합의했습니다.[150][151][152] 단지에는 옥상에 4층 레스토랑이 포함됩니다.[150] 워너브라더스. 프랭크 오를 고용했습니다 게리는 그 가게를 디자인했고, 게리는 1997년 초에 그의 계획을 발표했습니다. 제안서는 가장 낮은 8층을 홈으로 파고들어 전면을 반투명 철망으로 교체할 것을 요구했습니다.[153][154]

제임스타운 소유권

1990년대 후반과 2000년대

리먼 브러더스는 1997년 6월 원 타임스 스퀘어를 제임스타운 L.P.에 매각했는데, 이는 리먼 브러더스가 불과 2년 전에 이 건물에 지불한 금액의 4배에 달하는 약 1억 1천만 달러에 달했습니다.[139][155] 셔우드 에쿼티는 이 건물의 소수 지분을 소유하고 있었고, 소매 공간의 임대 대행사였습니다.[156] 워너 브라더스 매장은 1998년 4월에 3층 15,000 평방 피트 (1,400 m2)를 차지하며 문을 열었습니다.[157][158] 이 매장은 주소를 참조한 "1 툰 스퀘어"로 알려졌습니다.[159] 1999-2000년 새해맞이 행사를 앞두고 원 타임스 스퀘어의 지붕 위에 있던 공이 다시 한번 교체되었습니다.[160] 1999년 3월, 건물의 외부 간판의 일부가 무너진 후, 뉴욕시 건축부는 건물의 광고판 중 4개를 철거하라고 명령했습니다.[161]

타임 워너는 2001년 중반에 사업이 쇠퇴함에 따라 그 해 10월에 워너 브라더스 매장을 폐쇄할 것이라고 발표했습니다.[162][163] 타임 워너는 빈 소매 공간에 대한 임대료를 계속 지불했습니다.[164] 2002년에는 세븐일레븐 편의점, 타임스퀘어 브루어리, 원타임스퀘어 투부츠 피자의 계획이 발표되었습니다.[165] 하지만 예정되어 있던 세븐일레븐 매장은 결국 취소되었습니다.[166] 제임스타운은 그 후 2000년대 중반에 건물 전면의 450개의 패널을 수리했습니다. 이 프로젝트가 진행되는 동안, 2004년에 파사드의 패널들 중 하나가 땅에 떨어져 두 명의 보행자들이 다쳤습니다.[167]

건물의 작은 크기 때문에 2000년대와 2010년대에는 타임스퀘어 볼 드롭을 담당하는 제작사인 사무실 세입자 한 명만 수용했습니다.[168] 2006년 초, 저층부는 J. C. Penny가 운영하는 팝업 스토어로 J. C. Penny Experience(J. C. Penny Experience)로 알려져 있습니다.[169][170] 약국 체인 월그린은 2007년 건물 전체를 임대해 [171][172]연간 400만 달러를 지불했습니다. 이 체인점은 이전에 1970년까지 40년 동안 이 건물에서 매장을 운영했습니다.[156] 월그린스는 2008년 11월 이 공간에 새로운 플래그십 스토어를 열었습니다.[173][174] Gilmore Group은 매장 오픈의 일환으로 D3 LED로 제작된 전면부의 디지털 사인을 디자인했습니다. 17,000 평방 피트(1,600 미터2)의 표지판은 건물의 서쪽과 동쪽 높이를 대각선으로 따라 달리며 1,200만 개의 LED를 포함하고 있어 근처에 있는 나스닥 마켓 사이트 표지판을 타임스퀘어에서 가장 큰 LED 표지판으로 능가했습니다.[34][175] 이 표지판은 하루에 20시간씩 작동하며 월그린의 제품을 광고했습니다.[173]

2010년대부터 현재까지

2017년 9월, 제임스타운은 빈 공간의 많은 부분을 사용할 계획을 발표했습니다. 제안에 따라 15층부터 17층까지는 타임스퀘어 역사를 전담하는 박물관이 들어서고, 18층에는 새로운 전망대가 들어설 예정입니다.[176] 그 당시, 그 건물의 광고판들은 인터랙티브 프로그램의 인기가 높아짐에 따라 날짜가 붙기 시작했습니다.[177] 또한 지상층은 건물 바로 아래에 있는 뉴욕 지하철 타임스퀘어-42번가 역의 확장된 출입구를 제공하기 위해 개조될 예정입니다. 지하철 출입구 공사는 당초 2018년에 마무리될 예정이었으나,[176] MTA는 2019년 8월이 되어서야 42번가 셔틀 재건축 공사를 시작했습니다.[178][179][180] 원 타임스 스퀘어 재개발의 일환으로, 유리 캐노피가 있는 폭 20피트(6.1m)의 새로운 계단 입구와 새로운 엘리베이터 입구가 지어질 예정입니다.[178] 엘리베이터를 포함한 4천만 달러의 새로운 역 출입구는 2022년 5월에 공식적으로 문을 열었습니다.[181][182]

제임스타운은 2019년 1월 당시 광고판으로 완전히 막혀있던 건물을 개보수하고 상층부를 임대할 계획이라고 발표했습니다. 제임스타운은 월그린스의 임대 계약을 해지하거나 약국 규모를 축소할 계획도 세웠습니다.[183][184] 리얼딜 잡지는 제임스타운이 건물의 광고판으로부터 매년 2,300만 달러를 벌고 있다고 추정했습니다.[183] 같은 해 말, 타워 전면의 개별 광고판 화면은 1312×7380 픽셀의 해상도로 350피트(110m) 높이의 삼성 LED 디스플레이로 대체되었습니다. 스크린을 설치하려면 지퍼를 제거해야 했습니다.[185][186][187] 건물 기지에 있는 월그린 매장은 2022년까지 영구적으로 문을 닫았습니다.[188]

제임스타운은 2022년 5월 5억 달러를 들여 1 Times Square를 개조하기 시작했습니다.[189][190] 제임스타운은 프로젝트의 자금 조달을 위해 JP모건체이스로부터 4억2500만 달러의 모기지 대출과 8870만 달러의 빌딩 대출, 3980만 달러의 프로젝트 대출을 받았습니다.[191][192] AECOM과 Tishman Construction이 일반 계약자였고, S9 Architecture가 개조를 설계했습니다. 북쪽 정면의 광고판은 그대로 있었지만, 나머지 3면의 광고판은 철거되었습니다. 1960년대 대리석 전면은 제거되고 유리 커튼월로 대체됩니다.[193] 이 구조물은 다시 문을 연 후 사무실 공간의 단 하나의 층을 포함할 것입니다; 박물관은 6층을 차지할 것입니다.[168] 기술 회사는 대화형 명소를 위해 12층을 임대할 수 있습니다.[168][177] 이 건물의 전망대는 연중무휴로 운영되며, 타임스퀘어 볼은 1년 내내 하루에도 몇 번씩 떨어질 것입니다.[177] 제임스타운은 또한 건물의 전망대에 새로운 엘리베이터를 설치할 것입니다.[176][177] 이 건물은 북쪽 정면에 광고를 계속 전시할 것이며 2024년에 완공될 리노베이션 동안 새해 전야 행사를 개최할 것입니다.[189][190] 이웃한 4개의 타임스퀘어를 소유하고 있던 더스트 단체는 2022년 7월 원 타임스퀘어 주변의 비계가 보도의 혼잡을 악화시키면서 범죄를 끌어들일 것이라고 주장하며 도시의 DOB를 고소했습니다.[194]

건축

아이들리츠 & 맥켄지는 원래 원 타임 스퀘어를 신고딕 스타일로 디자인했습니다.[195][196] 보도에 따르면 이 양식은 불규칙한 모양의 부지 때문에 건축가들이 신고전주의 또는 신 르네상스 건물을 디자인하는 것을 방해했기 때문에 사용되었습니다.[6][8] 타임스는 이 건물이 가장 깊은 지하층에서 탑의 깃대 꼭대기까지 측정된 높이가 476피트(145m)라고 묘사했습니다.[197][196] 가로 높이에서 지붕선까지의 실제 높이는 362피트 8.75인치(111m)로, 문을 열었을 때 파크 로우 빌딩 다음으로 도시에서 두 번째로 높은 오피스 빌딩이 되었습니다.[196][198] 타워가 없는 타임 빌딩은 높이가 69m인 228피트 밖에 되지 않습니다.[199] 타임즈지의 데이비드 던랩(David W. Dunlap)은 건물이 완공되었을 때, "건물 높이는 가장 낮은 수준에서 측정되어야 한다고 주장하는 것은 그의 고용주의 이익에 부합하는 것"이라고 썼습니다.[198]

정면

타임스 타워가 문을 열었을 때, 그것은 석회암과 병마용으로 정교하게 장식된 정면을 포함하고 있었습니다. 정면의 아티큘레이션은 기둥의 구성 요소와 유사한 세 개의 수평 섹션, 즉 베이스, 샤프트 및 캐피털로 구성되었습니다.[6][195] 정면에는 건물 상부 구조물의 철골 기둥의 위치를 나타내는 약간 돌출된 부분이 여러 개 있었습니다.[6][200] 이 건물의 남쪽 부분은 42번가에서 60피트(18m) 정도 뒤로 뻗어 있었고 북쪽 부분보다 더 높았습니다.[6][7] 부지의 남쪽이 넓기 때문에 임대 가능한 공간이 증가했습니다.[6][8] 건물에 사용된 판유리의 무게는 28톤(길이 25톤, 무게 25톤)이었습니다.[201]

처음 세 개의 층은 정교하게 장식되었고, 내구성을 위해 선택된 재료인 크림색의 인디애나 석회암으로 덮여 있었습니다. 브로드웨이와 7번가 모두에 정교하게 조각된 출입구가 있었고, 3층 위에는 석회암으로 된 수평 띠 코스가 있었습니다.[195] 아래층 장식 중 일부는 1층 창문을 포함하여 철로 만들어졌습니다.[202] 바닥의 창문은 평소보다 더 작았고, 그래서 거대한 느낌을 주었습니다.[6][8] 갱도를 구성하는 4층부터 12층까지는 장식이 거의 없었습니다.[25] 이 이야기들은 크림색 벽돌로 덮여 있었는데, 이 벽돌은 정면의 나머지 부분에 있는 테라코타를 닮기 위해 유약을 발랐습니다.[195] 위층에는 브라켓과 코니와 같은 매우 화려한 테라코타 세부 사항이 포함되어 있습니다.[195][202] 12층 위에는 장식용 철공 창틀이 있었습니다.[202][203]

16층 이상은 북쪽 부분의 지붕이 철사 유리로 되어 있었습니다.[201] 건물의 남쪽 절반 위에 있는 사다리꼴 모양의 "타워"는 정사각형의 야영장을 닮도록 디자인되었습니다. 이 탑의 각 높이에는 아치형 창 하나가 하나씩 있고 그 옆에 작은 단일 창이 있습니다.[200] 비평가들은 이 탑의 세부 사항을 피렌체의 조토의 캄파닐레와 비교했습니다.[84][204] American Architect 잡지의 Arthur G. Bein은 "건축가는 위에 구멍이 뚫린 파라펫으로 조토의 거대한 기계로 장식된 코니스를 거의 정확하게 재현할 수 있었습니다."[204]라고 말했습니다. 탑의 각 모서리에는 포탑과 유사한 방식으로 설계된 돌출 교각이 있습니다.[204] 원래, 아이들리츠는 건물의 남쪽 부분 위에 돔을 지을 계획이었지만, 불규칙한 사다리꼴 모양의 덩어리 위에 원형 돔을 배치하는 것이 어렵다는 이유로 이 계획들을 폐기했습니다.[205]

1965년, 그 건물의 원래 정면은 420개의 콘크리트와 대리석 패널로 대체되었습니다. 각 패널은 5인치 두께(13cm)의 프리캐스트 콘크리트 층으로 만들어졌습니다. 7 ⁄ 8 인치 두께(2.2 cm)의 흰색 버몬트 대리석 층. 이 중 20개의 패널은 9 x 18 피트 (2.7 x 5.5 m), 나머지 400개의 패널은 9 x 12 피트 (2.7 x 3.7 m)로 측정되었습니다. 각 패널의 후면은 건물의 상부 구조에 고정되어 있었습니다.[206]Progressive Architecture 잡지는 이 보수 작업이 "철저하게 진행되는 싱겁기만 한 체면을 세우는 일"이라고 비판했습니다.[78][80] 1990년대에는 4개 층의 전면이 모두 광고판으로 덮여 있었습니다.[149] 2022년[update] 현재, 서부, 남부, 동부 지역의 콘크리트 및 대리석 전면은 제거되고 유리 패널로 교체되고 있습니다.[193]

구조적 특징

하부구조

건물의 기초는 깊이가 60피트(18m)까지 확장되었고 기반암 층까지 굴착되었습니다. 방수 옹벽으로 둘러싸여 있으며, 이 옹벽은 느슨한 돌과 시멘트가 섞인 상태로 다시 채워집니다.[207] 기초 자체는 건물의 철 기둥 위에 있는 주철 기둥으로 구성되어 있습니다. 이 바닥은 가로 5피트, 세로 1.5m 크기이며, 중앙은 17피트(5.2m) 간격으로 떨어져 있습니다. 각 강철 바닥은 가로 8 x 세로 8피트(2.4 x 2.4m), 두께 2피트(0.61m)의 무거운 화강암 블록의 맨 위에 놓여 있으며, 이는 다시 기반 암반 위에 직접 놓여 있습니다.[208][209] 상층의 구조적 하중은 바닥으로 내려간 다음 기반암 층을 가로질러 퍼집니다. 기반암 층은 평방 피트당 20톤의 짧은 하중을 운반합니다(280psi; 1,900kPa).[24] 기초의 옹벽은 붉은 벽돌로 만들어졌습니다.[201] 현장의 동쪽 부분(밑돌이 위로 경사지는 곳)에는 I빔이 내장된 옹벽을 건설하여 추가적인 바람막이를 제공했습니다.[209]

이 건물은 지하 3층으로 구성되어 있으며, 그 중 가장 낮은 층은 깊이가 55피트(17m)입니다. 타임스퀘어 지하철역은 지하 1층과 2층의 일부를 침범합니다.[208][210] 지하철역 자체는 지하 22피트(6.7m)에 위치해 있고, 10피트(3.0m) 높이의 천장을 가지고 있습니다.[211] 지하철 터널의 기둥은 벽돌로[201] 덮여 있었고 방음 모래 쿠션 위에 놓여 있어 지하철 열차가 지나갈 때 발생하는 진동을 최소화했습니다.[207][212][209] 지하철 터널 위에는 상부 구조물의 일부가 기울어져 있는데, 이는 시의 교통안전위원회가 지하철 터널의 통행권을 방해하는 행위를 금지했기 때문입니다.[209][213] 북쪽 벽은 지하철 터널 위에 있는 30톤짜리 판형 거더 위에 놓여 있습니다. 건설 당시, 그것은 사무실 건물에 설치된 것 중 세계에서 가장 무거운 거더였습니다.[202][212][214][c] 이 거더는 길이가[215] 60피트(18m)이며 3개의 I빔 그룹으로 구성되어 있으며, 총 너비는 3피트(0.91m), 높이는 5피트(1.5m)입니다.[202] 지하에 있는 각각의 높이가 43피트(13m)인 7개의 교각이 상부 층의 전체 구조 하중을 운반합니다.[215] 이 교각들은 포틀랜드 시멘트로 둘러싸여 있습니다.[208]

상부구조

상부 구조물에는 2층 높이의 강철 기둥 섹션이 포함되어 있습니다. 각 층에서 기둥은 강철 대들보 격자에 의해 수평으로 연결됩니다.[216] 평균적으로 각 거더의 길이는 25피트(7.6m)이며 각 층에 사용되는 강철 조각은 약 150개입니다.[24] 7개의 주요 구조 기둥은 각 층의 벽 안에 내장되어 있습니다.[216] 구조 기술자 퍼디와 헨더슨은 건물을 위한 세 가지 바람막이 시스템을 설계했습니다.[209][217] 첫 번째 시스템은 각 층의 거더로 구성되어 있으며 거셋 플레이트를 통해 건물 기둥에 용접됩니다.[212][217] 이 건물은 또한 "X"자 모양의 대각선 브레이싱을 포함하고 있으며, 각 엘리베이터 샤프트 옆의 칸막이 안에 배치되어 있습니다. 개별 엘리베이터 샤프트 사이에는 무릎 브레이싱 시스템이 있습니다. 이 시스템은 수평 거더의 중앙에서 아래로 연장되는 회전된 "K" 모양의 대각선 철봉으로 구성됩니다.[217] 구조용 철골은 제곱피트당 46파운드(2.2kPa)의 사하중을 받았습니다.[202]

원래, 대들보 사이의 공간은 속이 빈 벽돌로 만들어진 평평한 아치들로 덮여 있었고, 그런 다음 시멘트 층으로 덮여 있었습니다. 그런 다음 이 평평한 아치 위에 내화 목재 침목을 설치하고 이 침목 위에 내화 목재 층을 설치했습니다. 그런 다음 완성된 나무 바닥을 내화 목재 층 위에 설치했습니다.[216] 칸막이 벽은 정사각형 벽돌로 만들어졌고, 그 다음 석고로 마감되었습니다. 건물의 엘리베이터 샤프트는 불 점토로 만들어진 벽으로 둘러싸여 있었고, 그 다음 타일 벽돌 층으로 덮여 있었습니다.[216] 상부 구조물은 철, 벽돌, 모르타르, 병마용, 석회암, 석조 및 기타 재료로 8,292만 파운드(41,000 ST, 37,000 LT, 38,000 t)를 사용했습니다.[202][214]

내부

처음에 브로드웨이의 입구는 장식용 기둥이 있는 엘리베이터 로비로 이어졌고, 7번가의 입구는 장식용 계단으로 이어졌습니다. 로비에는 15.5피트(4.7m) 높이의 천장이 있었습니다. 벽의 가장 낮은 부분은 높이가 8피트(2.4미터)인 대리석으로 된 견직물을 포함하고 있었고, 벽의 위쪽 부분은 흰색으로 칠해져 있었습니다. 본당의 상단에는 조개를 모티브로 장식된 패널로 장식된 코니스가 포함되어 있습니다. 바닥은 흰색 모자이크로 만들어졌습니다.[218] 건물 안에는 오크 재질의 회전문이 7개 있었습니다. 로비로 향하는 브로드웨이 입구에 2개, 42번가 입구에 1개, 지하에 있는 지하철역으로 통하는 4개.[203]

지하 1층에는 여러 개의 작은 상점이 있는 보행자 오락실이 있었는데, 이 오락실은 거리에서 타임스퀘어 역의 남쪽 방향 승강장까지 이어졌습니다.[219] 오락실은 1967년에 높은 범죄로 인해 문을 닫았지만,[220] 역에서 원 타임스 스퀘어의 지하로 이어지는 아치형 도로는 2000년대까지 볼 수 있었습니다.[221] 지하 1층의 나머지 부분에는 상점 전선과 타임스의 우편 부서가 있었고 지하 2층에는 우편 및 수리 부서가 있었습니다.[208] 지하 3층은 다른 지하층보다 넓으며 인도 아래에서 사방의 연석선까지 확장되어 있습니다.[207] 17,000평방피트(1,600m2)의 면적을 차지하며, 위의 각 사무실 층보다 3배 더 큽니다.[222] 지하 3층에는 화물 엘리베이터를 통해 지하 2층으로 연결된 프레스룸이 있었습니다.[208] 기자실의 남쪽 부분에는 원래 4개의 인쇄기가 있었습니다.[207] 기자실은 42번가와 7번가에 있는 통로에 의해 불이 켜졌는데, 이 통로는 깊이가 30피트(9.1m)이고 유리 벽돌로 된 피복이 들어 있었습니다.[207] 타임스퀘어 역의 남쪽 방향 승강장뿐만 아니라 이 도로들도 유리로 된 스카이라이트로 뒤덮였습니다.[223]

지상의 첫 12층은 뉴욕 타임즈 출판사를 제외한 다른 세입자들에게 임대되었습니다.[218][224] 13층부터 21층까지는 뉴욕 타임즈의 다양한 부서들이 포함되어 있었습니다.[225] 각 사무실은 장식용 고깔과 붉은 오크 문으로 장식되었습니다.[218] 사무실은 건물의 가장 북쪽 60피트(18m)를 차지하고 있었는데, 이는 매우 좁았습니다. 건물의 남쪽 절반에는 각 층의 중간마다 복도가 이어져 서쪽과 동쪽으로 사무실이 분리되어 있었습니다.[226] 이 복도는 흰색 모자이크 타일 바닥과 벽에 대리석 무늬를 칠한 것으로 장식되었습니다.[203] 작곡실로 사용된 16층은 건물의 북쪽 부분에서 가장 높은 층이었습니다. 타임스의 편집국이 포함된 상위 6개 층은 4면 모두 창문이 있었습니다.[226] 모든 사무실은 창문에서 23피트(7.0m) 이내에 위치해 있었고, 건물은 내부 사무실에 자연광을 제공할 수 있는 광축이 없을 정도로 좁았습니다.[200][212] 건물이 완공되면 각 사무실은 매일 최소 5시간 동안 자연광으로 조명을 받았습니다.[201]

타워 지하에 있는 이전의 전기실은 타임스퀘어의 새해 전야 행사와 관련된 물품들을 보관하는 "금고" 역할을 하고 있는데, 여기에는 공 자체(2009년 이전에는 타워 맨 위에 연중 전시되는 날씨에 견디는 버전으로 교체되었습니다), 여분의 부품, 숫자 표지판 및 기타 기념품들이 포함됩니다.[227] 타워 꼭대기 근처의 방에는 조명 컨트롤러와 윈치를 포함한 공의 전자 제품도 있습니다.[228][229]

기계적 특징

건물의 서쪽에는 계단과 엘리베이터가 놓여 있었고,[226] 계단과 엘리베이터 옆에는 각 층마다 화장실이 있었습니다.[230] 건물이 지어졌을 때 7개의 엘리베이터와 인쇄기, 펌프, 선풍기를 포함한 100개가 넘는 다른 기계 장치가 있었습니다.[231][232] 이 중 엘리베이터 5대는 승객용, 2대는 화물용이었습니다.[233] 이 건물의 엘리베이터 2대(승객 1대, 화물 1대)는 지하에서 지상층까지 운행했고, 나머지 엘리베이터는 16층까지만 운행했습니다.[234] 모든 승객용 엘리베이터는 분당 500피트(150m/min)로 운행할 수 있지만, 이 엘리베이터 중 하나는 중장비 운반에 사용될 수 있으며 분당 25피트(7.6m/min)로 속도를 줄일 수 있어 운반 능력이 두 배로 증가했습니다.[233] 엘리베이터 캡은 원래 벽마다 거울이 있는 구리 케이지였습니다.[235]

건물에는 각각 200마력(150kW)의 출력을 낼 수 있는 보일러 2대가 있었습니다. 스팀 라이저는 보일러의 열을 542개의 라디에이터로 분배했습니다.[201] 뉴욕시 상수도 시스템의 물을 지하로 끌어들여 분당 250 US 갤런(950 L)의 속도로 여과했습니다. 그런 다음 여과된 물을 23층까지 퍼올려 다른 층에 배포했습니다.[223] 불이 날 경우를 대비해 지하에는 1만 US갤런(3만8천L)급 물탱크가, 23층에는 3천 US갤런(1만1천L)급 물탱크 2개가 있었습니다.[236] 총 용량이 600 미국 갤런(2,300 L)인 3개의 하수 펌프가 건물 밖으로 폐수를 퍼내는 데 사용되었습니다.[203] 게다가 지하실에서 16층까지 가스관이 뻗어 있었습니다.[223]

실외 공기는 거리 높이의 공기 흡입구와 지하의 공기 필터로 흡입되었고, 여과된 공기는 사무실로 분배되었습니다. 건물의 7번가 쪽에는 건물 외벽을 마주하고 각 층의 계단, 엘리베이터, 화장실로 둘러싸여 있는 높이 389피트(119m)의 환기 파이프가 있었습니다. 여름 동안 대형 선풍기가 환기 파이프를 통해 퀴퀴한 공기를 위로 밀어 올렸습니다.[230] 건물에는 2,400개의 전기 콘센트와 6,200개 이상의 램프도 있었습니다.[201][202] 사무실은 2층에서 14층까지 150개의 화려한 샹들리에로 빛났습니다.[223] 원래 건물에는 74마일(119km)의 전선과 21마일(34km)의 전선이 있었습니다.[202][214]

빌보드

원 타임스 스퀘어의 첫 번째 전광판은 1996년에 설치되었습니다. 증기 효과가 있는 컵 누들 광고판이 타워 전면에 추가되었고, 나중에 애니메이션 버드와이저 간판이 추가되었습니다. 지난 10월, ITT Corporation이 후원하는 55피트짜리 비디오 스크린이 탑 꼭대기에 소개되었는데, 이 스크린에는 비디오 광고와 사회봉사 안내 방송이 실릴 예정입니다.[149][237] 1996년 12월, NBC에서 운영하는 Astrovision이라는 파나소닉 디스플레이가 탑의 바닥에 소니의 점보트론을 대체하는 것으로 소개되었습니다.[238][34]

1997년 건물의 매각과 관련된 서류에 따르면 타워의 광고판은 연간 700만 달러의 순이익을 창출하고 있으며 [139]이는 300%의 이익을 나타내고 있습니다.[239] 2005년에 Sherwood Equesties의 회장 Brian Turner는 매년 2억명 이상의 사람들이 Times Square Ball이 건물에 떨어지는 것을 봤다고 추정했습니다.[240] (연간 평균 1억 명이 넘는 보행자와 함께, 매년 다양한 청중에 의해 시청되는 새해 축제에 대한 언론 보도의 중요성과 함께), 타임스퀘어 지역의 증가하는 관광과 높은 교통량으로 인해, 2012년까지 이 표지판의 연간 수익은 2,300만 달러 이상으로 증가하여 런던의 피카딜리 서커스가 세계에서 가장 가치 있는 공공 광고 공간으로 부상했습니다.[241][242]

광고주

1996년부터 2006년까지 닛신 식품은 매연 효과가 있는 컵 누들 광고판(Cup Noods)을 운영했습니다.[149] 컵 누들 광고판은 2006년에 쉐보레 브랜드의 시계를 특징으로 하는 제너럴 모터스 광고판으로 대체되었습니다. GM의 파산과 조직 개편에 따른 감원으로 2009년 쉐보레 시계가 퇴출됐고 결국 기아차 광고판으로 대체됐습니다. 이 광고판은 2010년에 던킨도너츠 디스플레이로 대체되었습니다.[243]

1998년 Discover Card는 ITT Corporation을 대신하여 10년 계약의 일환으로 One Times Square의 최상위 화면의 운영자 및 후원자가 되었습니다. 이 계약은 디스커버 카드가 1999-2000년 타임스퀘어의 축제의 공식 후원사가 될 것이라는 발표와 함께 이루어졌습니다.[243]

뉴스 코퍼레이션(후에 21세기 폭스로 개명)은 2006년에 NBC를 대체하여 아스트로비전 스크린의 운영자 및 후원자가 되었습니다.[244] 소니는 2010년 뉴스 코퍼레이션을 대체하여 원 타임스 스퀘어로 복귀했습니다. 새로운 고화질 LED 디스플레이를 갖춘 파나소닉 스크린입니다.[245]

2007년 12월, 도시바는 Discover Card로부터 10년 임대로 One Times Square의 최상위 화면에 대한 후원을 받았습니다.[246] 화면에는 도시바 제품 뿐만 아니라 일본 관광에 관한 영상도 표시되어 있었습니다.[247] 2008년에는 도시바 고화질 LED 디스플레이(도시바 비전)를 새로 설치하고 더 큰 새해 전야 무도회를 수용하기 위해 지붕을 재설계하는 등 원 타임스 스퀘어 상부로의 업그레이드가 시작되었으며, 이는 2009년부터 건물의 연중 고정 장치가 되었습니다.[227][248] 도시바는 지속적인 비용 절감 조치를 이유로 2018년 초 원 타임스 스퀘어 후원을 종료할 것이라고 발표했습니다.[247][249][250]

참고문헌

메모들

- ^ 이곳은 59번가 남쪽에 위치한 4개의 북향 부지 중 하나로 브로드웨이와 또 다른 거리, 크로스타운 거리가 합쳐져 형성되었습니다. 플랫아이언 빌딩은 매디슨 스퀘어 남쪽의 23번가와 5번가에 있는 삼각형 부지에 지어졌습니다. 헤럴드 스퀘어 남쪽 34번가와 6번가에 있는 부지에 공원이 지어졌습니다. 콜럼버스 서클 남쪽 59번가와 8번가에 있는 곡선 부지는 현재 2 콜럼버스 서클이 차지하고 있습니다.[8]

- ^ 이제 3개의 Times Square, 4개의 Times Square, 5개의 Times Square 및 Times Square 타워

- ^ 보스턴의 콜로니얼 극장 위에는 더 큰 거더가 사용되었습니다.[215]

인용

- ^ "One Times Square". CTBUH Skyscraper Database. Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat. 2016. Archived from the original on November 17, 2016.

- ^ "Allied Chemical Building". CTBUH Skyscraper Database. Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat. 2016. Archived from the original on November 18, 2016.

- ^ "1 Times Square". Emporis. 2016. Archived from the original on March 5, 2016.

- ^ a b c "1475 Broadway, 10036". New York City Department of City Planning. Archived from the original on September 28, 2021. Retrieved March 25, 2021.

- ^ a b White, Norval; Willensky, Elliot; Leadon, Fran (2010). AIA Guide to New York City (5th ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. p. 271. ISBN 978-0-19538-386-7.

- ^ a b c d e f g Landau & Condit 1996, 312쪽.

- ^ a b "A New Building for the New York Times; Plans for a Monumental Structure on Long Acre Square. The Architectural and Other Features of the Building Which Is Being Erected at the New Centre of Travel and Activity on Manhattan Island". The New York Times. June 27, 1903. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 6, 2022. Retrieved August 6, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e 뉴욕 타임즈 빌딩 부록 1905, 페이지 BS7.

- ^ a b "Allied Chemical Wins Times Square Address". The New York Times. September 7, 1966. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 5, 2022. Retrieved August 5, 2022.

- ^ a b Dunlap, David W. (July 15, 1990). "Addresses in Times Square Signal Prestige, if Not Logic". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 10, 2022. Retrieved August 9, 2022.

- ^ "MTA Neighborhood Maps: Times Sq-42 St (S)". mta.info. Metropolitan Transportation Authority. 2018. Archived from the original on August 29, 2021. Retrieved September 13, 2018.

- ^ "New Subway Company Buys Broadway Site; The Deal May Foreshadow Station Changes at 42d Street". The New York Times. April 25, 1901. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on September 4, 2022. Retrieved August 6, 2022.

- ^ a b c "A New Home for the New York Times; The Newspaper to Move Up Town Early in 1904. It Is to Have a Modern Steel-Construction Building on the Triangle at Broadway, Seventh Avenue and West 42d Street". The New York Times. August 4, 1902. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on September 4, 2022. Retrieved August 6, 2022.

- ^ "Found Place Where Young Bought Trunk; Dealer and His Son Say Purchaser Was Clean Shaven". The New York Times. September 25, 1902. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 6, 2022. Retrieved August 6, 2022.

- ^ a b Talese, Gay (August 24, 1963). "Times Square Loses Name That Abided 60 Years; Immortalization in Granite Proves All Too Mortal Refacing of Times Tower to Remove Thorley 'Plaques' A Budding Career Lease at $4,000 a Year". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 5, 2022. Retrieved August 5, 2022.

- ^ a b c "Douglas Leigh New Owner: 'Times' Sells Times Tower; Exhibition Hall Is Planned". New York Herald Tribune. March 16, 1961. p. 1. ISSN 1941-0646. ProQuest 1326871256.

- ^ Dunlap, David W. (March 17, 1999). "Former Times Building Is Named a Landmark". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on June 5, 2020. Retrieved July 14, 2020.

- ^ (Former) New York Times Building (PDF) (Report). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. March 16, 1999. p. 6. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 4, 2021. Retrieved August 6, 2022.

- ^ a b c New York Times Building (originally the Times Annex) (PDF) (Report). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. April 24, 2001. pp. 2–3. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 28, 2021. Retrieved August 5, 2022.

- ^ "Leases—Borough of Manhattan". The Real Estate Record: Real estate record and builders' guide. Vol. 70, no. 1795. August 9, 1902. p. 209. Archived from the original on August 6, 2022. Retrieved August 6, 2022 – via columbia.edu.

- ^ Hood, Clifton (1978). "The Impact of the IRT in New York City" (PDF). Historic American Engineering Record. p. 182. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 17, 2021. Retrieved December 20, 2020.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.{{cite web}}: CS1 메인: 포스트스크립트 (링크) - ^ a b "New Home for "The Times": It Announces Plans for Its Uptown Building". New-York Tribune. August 4, 1902. p. 7. ProQuest 571264569.

- ^ a b c 뉴욕 타임즈 빌딩 부록 1905, 페이지 BS18.

- ^ a b c "Enormous Weight of Modern Structures; Uneven Pressures to Contend With in the New Times Building. Skeleton Frame Going Up at the Rate of About Three Stories a Week – How All the Steel Is Tested". The New York Times. November 29, 1903. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on September 4, 2022. Retrieved August 6, 2022.

- ^ a b "New Times Building Cornerstone Laid; Bishop Henry C. Potter Invokes Blessings on the Structure". The New York Times. January 19, 1904. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on September 4, 2022. Retrieved August 7, 2022.

- ^ "Bishop Potter at the Ceremony: Offers Prayer at Laying of Cornerstone of New Times Building". New-York Tribune. January 19, 1904. p. 6. ProQuest 571528689.

- ^ "To Be Called Times Square; Aldermen Vote to Rename Long Acre Square, Site of New Times Building". The New York Times. April 6, 1904. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 7, 2022. Retrieved August 7, 2022.

- ^ "Stop Building Work: Seventeen Unions Represented in New York Strike". The Washington Post. August 2, 1904. p. 5. ISSN 0190-8286. ProQuest 144508368.

- ^ "Big Strike in New York: Work Stopped on a Number of Important Buildings". The Hartford Courant. August 2, 1904. p. 1. ISSN 1047-4153. ProQuest 555246037.

- ^ 뉴욕 타임즈 빌딩 부록 1905, 페이지 BS18–BS19.

- ^ "Election Results by Times Building Flash; Steady Light Westward – Roosevelt; Eastward – Parker". The New York Times. November 6, 1904. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 8, 2022. Retrieved August 8, 2022.

- ^ "To-day's Times Issued From Its New Home; Delicate Task of Removal Was Well Completed". The New York Times. January 2, 1905. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 8, 2022. Retrieved August 8, 2022.

- ^ Brainerd, Gordon (2006). Bell Bottom Boys. Infinity Publishing. p. 58. ISBN 9780741433992. Archived from the original on August 5, 2022. Retrieved September 16, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f Crump, William D. (2014). Encyclopedia of New Year's Holidays Worldwide. McFarland. p. 242. ISBN 9781476607481. Archived from the original on June 19, 2022. Retrieved September 16, 2020.

- ^ a b c d Boxer, Sarah B. (December 31, 2007). "NYC ball drop goes 'green' on 100th anniversary". CNN. Archived from the original on January 3, 2014.

- ^ "Great Drug Store to Be in the Times Building; Hegeman & Co. to Have One of the Largest in the World". The New York Times. July 31, 1905. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 8, 2022. Retrieved August 8, 2022.

- ^ "News Will Be Plashed from the Tower of The Times Building on Tuesday Night". The New York Times. November 5, 1905. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 8, 2022. Retrieved August 8, 2022.

- ^ "Music by Wireless to the Times Tower; Telephone Messages Also Received Through the Ether". The New York Times. March 8, 1907. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 8, 2022. Retrieved August 8, 2022.

- ^ a b c McKendry, Joe (2011). One Times Square: A Century of Change at the Crossroads of the World. David R. Godine Publisher. pp. 10–14. ISBN 9781567923643. Archived from the original on October 10, 2017. Retrieved September 16, 2020.

- ^ a b c Lankevich, George J. (2001). Postcards from Times Square. Square One Publishers. p. 20. ISBN 9780757001000. Archived from the original on August 5, 2022. Retrieved September 16, 2020.

- ^ Nash, Eric P. (December 30, 2001). "F.Y.I." The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 12, 2022. Retrieved August 12, 2022.

- ^ "What's Your Problem?". Newsday. December 30, 1965. p. 48. ISSN 2574-5298. Archived from the original on July 18, 2022. Retrieved July 18, 2022.

- ^ "Watch the Times Tower; The Descent of an Electric Ball Will Mark the Arrival of 1908 To-night". The New York Times. December 31, 1907. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 8, 2022. Retrieved August 8, 2022.

- ^ "Times Tower Gets Porto Rico Message; New Wireless Receiver Intercepts Dispatch After Other Stations Failed to Take It". The New York Times. January 18, 1908. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 8, 2022. Retrieved August 8, 2022.

- ^ "The Times to Flash Election Results; North Means "Taft," South "Bryan," West "Hughes," and East "Chanler"". The New York Times. November 2, 1908. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 8, 2022. Retrieved August 8, 2022.

- ^ "Loti Amazed by Times Tower View; Tells in His Impressions of New York How the City Frightened and Fascinated Him". The New York Times. February 23, 1913. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on September 2, 2022. Retrieved September 2, 2022.

- ^ "New York's Marvels Awe Sultan of Sulu; Kiram II. and His Suite Greatly Impressed by the View of the City from The Times Tower". The New York Times. September 25, 1910. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on September 2, 2022. Retrieved September 2, 2022.

- ^ "A Times Annex Near Times Square; Building 143 by 100 Is to be Constructed to Meet This Paper's Needs". The New York Times. March 29, 1911. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 16, 2022. Retrieved February 16, 2022.

- ^ The Times Annex: A Wonderful Workshop. The New York Times Company. 1913. p. 27.

- ^ "The "New York Times"". The Hartford Courant. February 4, 1913. p. 8. ISSN 1047-4153. ProQuest 555973270.

- ^ Ouroussoff, Nicolai (November 20, 2007). "Pride and Nostalgia Mix in The Times's New Home". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on June 14, 2021. Retrieved September 18, 2021.

- ^ "History of Times Square". The Telegraph. London. July 27, 2011. Archived from the original on March 10, 2016.

- ^ a b c Long, Tony (November 6, 2008). "Nov. 6, 1928: All the News That's Lit". Wired. Archived from the original on November 9, 2008.

- ^ "The New York Times Company Enters The 21st Century With A New Technologically Advanced And Environmentally Sensitive Headquarter" (PDF) (Press release). The New York Times Company. November 16, 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 27, 2008.

- ^ "Times Tower Fire Still a Mystery; Inspection Turns Up No Clue to Fatal Blaze's Origin". The New York Times. November 25, 1961. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 5, 2022. Retrieved August 5, 2022.

- ^ "Beacon on Times Building; Neon Light, Visible for 50 Miles, Adds to Brilliance of Square". The New York Times. September 1, 1928. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on September 2, 2022. Retrieved September 2, 2022.

- ^ a b c d "Huge Times Sign Will Flash News; Electric Bulletin Board, Used for the Election, Will Be in Nightly Operation". The New York Times. November 8, 1928. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on September 2, 2022. Retrieved September 2, 2022.

- ^ "14,800 Bulbs Give News to New York". The Gazette. November 9, 1928. p. 13. Archived from the original on September 2, 2022. Retrieved September 2, 2022.

- ^ a b "The Times' Famous News Sign Will Be 20 Years Old Saturday; Among First Moving Electric Bulletins Was Description of President Hoover's Election -- Many Momentous Stories Told". The New York Times. November 2, 1948. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on September 2, 2022. Retrieved September 2, 2022.

- ^ Young, Greg; Meyers, Tom (2016). The Bowery Boys: Adventures in Old New York: An Unconventional Exploration of Manhattan's Historic Neighborhoods, Secret Spots and Colorful Characters. Ulysses Press. p. 289. ISBN 9781612435763. Archived from the original on August 5, 2022. Retrieved September 16, 2020.

- ^ a b Poulin, Richard (2012). Graphic Design and Architecture, A 20th Century History: A Guide to Type, Image, Symbol, and Visual Storytelling in the Modern World. Rockport Publishers. p. 53. ISBN 9781592537792. Archived from the original on October 10, 2017. Retrieved September 16, 2020.

- ^ "The Times Electric News Sign Goes Dark Under New Dimout, Probably for Duration". The New York Times. May 19, 1942. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on September 2, 2022. Retrieved September 2, 2022.

- ^ "Election Result Signals Of Times Banned by War". The New York Times. November 1, 1942. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on September 2, 2022. Retrieved September 2, 2022.

- ^ Walker, Danton (October 22, 1943). "Broadway". New York Daily News. p. 129. ISSN 2692-1251. Archived from the original on September 2, 2022. Retrieved September 2, 2022.

- ^ a b "Times to Stop News Sign Today as 'Brownout' Aid". The New York Times. November 1, 1943. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on September 2, 2022. Retrieved September 2, 2022.

- ^ Watson, John (November 2, 1943). "Broadway Coyly Tests Brilliance As Dimout Ends: Some Theaters Blaze Forth, but Patches of Gloom Cloud First-Night Glory When the Lights Went On Again All Over New York". New York Herald Tribune. p. 38. ISSN 1941-0646. ProQuest 1284445041.

- ^ a b c d Gelder, Lawrence Van (December 11, 1994). "Lights Out for Times Square News Sign?". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on May 8, 2016. Retrieved August 9, 2022.

- ^ "The Times Electric Sign Attraction for Many Eyes". The New York Times. August 15, 1945. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on September 2, 2022. Retrieved September 2, 2022.

- ^ "Times Sq. Getting Vote Result Sign; 85-Foot Electric Indicator on Times Tower Will Give Returns at a Glance". The New York Times. October 24, 1952. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on September 2, 2022. Retrieved September 2, 2022.

- ^ "Times' Lighted 'Thermometer' Will Give the Election Returns". The New York Times. November 4, 1956. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on September 2, 2022. Retrieved September 2, 2022.

- ^ Asbury, Edith Evans (November 22, 1957). "Landmark Signs Dedicated Here; 20 Are first of Many That Will Mark Historical and Architectural Sites". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on October 29, 2019. Retrieved October 29, 2019.

- ^ a b "Times Tower Sold for Exhibit Hall; Douglas Leigh Buys 24-Story Building in the Square". The New York Times. March 16, 1961. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 5, 2022. Retrieved August 5, 2022.

- ^ a b "Times Tower Building In Times Square Sold To Allied Chemical: Firm Will Remodel Facility But Maintain the Traditions Of New York City Landmark". Wall Street Journal. April 17, 1963. p. 5. ISSN 0099-9660. ProQuest 132873722.

- ^ "Third Body Found in Times Sq. Fire; Porter as Well as 2 Firemen Died in Times Tower Blaze". The New York Times. November 24, 1961. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 5, 2022. Retrieved August 5, 2022.

- ^ "Times Tower Fire is Laid to Smoking; Cavanagh Says Blaze Began in Storeroom for Toys". The New York Times. December 19, 1961. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 5, 2022. Retrieved August 5, 2022.

- ^ a b "Headlines Again Circle Former Times Tower". The New York Times. March 9, 1965. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 5, 2022. Retrieved August 5, 2022.

- ^ a b Ennis, Thomas W. (April 17, 1963). "Old Times Tower to Get New Face; 26-Story Building Will Be Stripped and Recovered in Glass and Marble". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 21, 2022. Retrieved August 5, 2022.

- ^ a b "A la Recherche du TIMES Perdu" (PDF). Progressive Architecture. Vol. 44. May 1963. p. 82. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 5, 2022. Retrieved August 5, 2022.

- ^ "Benjamin Bailyn Is Dead at 55; Architect of the Allied Tower". The New York Times. July 23, 1967. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 5, 2022. Retrieved August 5, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e Stern, Robert A. M.; Mellins, Thomas; Fishman, David (1995). New York 1960: Architecture and Urbanism Between the Second World War and the Bicentennial. New York: Monacelli Press. p. 1103. ISBN 1-885254-02-4. OCLC 32159240. OL 1130718M.

- ^ "Modernization Project Begins on Times Tower". The New York Times. October 29, 1963. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 5, 2022. Retrieved August 5, 2022.

- ^ "Times Tower Due New Face: Structure Being Built on Original Framework". The Sun. February 24, 1964. p. 6. ProQuest 540133645.

- ^ "Times Tower Box of 1904 Unsealed". The New York Times. March 18, 1964. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 5, 2022. Retrieved August 5, 2022.

- ^ a b c Huxtable, Ada Louise (March 20, 1964). "Architecture: That Midtown Tower Standing Naked in the Wind: Skyscraper Buffs See Antique Skeleton Fancy Steel Framing Elaborated by Rivets". The New York Times. p. 30. ISSN 0362-4331. ProQuest 115725139.

- ^ Ennis, Thomas W. (January 31, 1965). "Marble-Clad Buildings Brighten Midtown Manhattan". The New York Times. p. R1. ISSN 0362-4331. ProQuest 116760160.

- ^ "Allied Tower Makes False Start on Facade". The New York Times. August 4, 1964. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 5, 2022. Retrieved August 5, 2022.

- ^ Gray, Christopher (November 28, 2014). "A Home for the Headlines". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on June 21, 2022. Retrieved September 2, 2022.

- ^ a b c "Electronic News Bulletins To Return to Times Square". Wall Street Journal. January 20, 1986. p. 1. ISSN 0099-9660. ProQuest 398033841.

- ^ "Highest Electric Signs In Times Sq. Go On Today". The New York Times. July 23, 1965. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on September 4, 2022. Retrieved August 5, 2022.

- ^ Buckley, Thomas (December 3, 1965). "Allied's Times Square Tower Dedicated by Gov. Rockefeller; Allied's Times Square Tower Dedicated by Gov. Rockefeller". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on September 4, 2022. Retrieved August 5, 2022.

- ^ "Old N.Y. Times Tower keeps up tradition". The Christian Science Monitor. December 17, 1965. p. 11. ISSN 0882-7729. ProQuest 510762391.

- ^ Lippa, Si (July 27, 1966). "Focus…: Allied Chemical: Tower of Strength: Do Additional Fabrics Loom In Allied Chemical's Future?". Women's Wear Daily. Vol. 113, no. 18. pp. 1, 45. ProQuest 1523514401.

- ^ "Allied Chemical Tower To Get an English Cafe". The New York Times. April 12, 1965. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 5, 2022. Retrieved August 5, 2022.

- ^ Claiborne, Craig (August 22, 1966). "Dining in a Modern Tower". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 5, 2022. Retrieved August 5, 2022.

- ^ "Fashion Rtw: Allied Tower Reported For Sale". Women's Wear Daily. Vol. 125, no. 56. September 21, 1972. p. 19. ProQuest 1523642418.

- ^ a b c Stetson, Damon (October 10, 1972). "'For Sale' Sign Is Posted At Allied Chemical Tower". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 5, 2022. Retrieved August 5, 2022.

- ^ a b c d "Developer Rents Allieds' Tower In Times Square". The Hartford Courant. November 1, 1973. p. 55. ISSN 1047-4153. ProQuest 551980429.

- ^ Tomasson, Robert E. (October 31, 1973). "Lessee Will Put Exhibits In Times Square Tower". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 5, 2022. Retrieved August 5, 2022.

- ^ a b Tomasson, Robert E. (November 18, 1973). "An Innovator Goes to Work in Times Square". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 5, 2022. Retrieved August 5, 2022.

- ^ a b "Times Tower Sign To Get Good News". The Washington Post. April 2, 1974. p. A14. ISSN 0190-8286. ProQuest 146202415.

- ^ a b c d Kaiser, Charles (May 15, 1975). "A Glittery Times Sq. Tower Due". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 5, 2022. Retrieved August 5, 2022.

- ^ a b Randall, Gabrielan (2000). Times Square and 42nd Street in Vintage Postcards. Arcadia Publishing. p. 16. ISBN 9780738504285. Archived from the original on August 5, 2022. Retrieved September 16, 2020.

- ^ a b c d Bloom, Ken (2013). Broadway: An Encyclopedia. Routledge. p. 530. ISBN 9781135950194. Archived from the original on August 5, 2022. Retrieved September 16, 2020.

- ^ a b c Josephs, Lawrence (January 3, 1982). "A New Owner Takes the Reins in Times Square". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on July 14, 2014. Retrieved August 5, 2022.

- ^ a b "A Prismatic Tower". The Washington Post. May 15, 1975. p. D2. ISSN 0190-8286. ProQuest 146376858.

- ^ "Mirrors Will Sheathe Times Square Tower". The New York Times. May 15, 1975. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 9, 2022. Retrieved August 9, 2022.

- ^ Asbury, Edith Evans (March 3, 1976). "Mayor and Mouse Open One Times Square". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 5, 2022. Retrieved August 5, 2022.

- ^ Doughtery, Philip H. (October 11, 1976). "Advertising: An Addition to Times Square". The New York Times. p. 5. ISSN 0362-4331. ProQuest 122847653.

- ^ a b Sagalyn, Lynne B. (2003). Times Square Roulette: Remaking the City Icon. MIT Press. p. 323. ISBN 9780262692953. Archived from the original on August 5, 2022. Retrieved September 16, 2020.

- ^ a b Horsley, Carter B. (November 15, 1979). "Razing of One Skyscraper to Build 3 New Ones Proposed in Times Sq". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 5, 2022. Retrieved August 5, 2022.

- ^ Stern, Fishman & Tilove 2006, 681쪽.

- ^ Goldberger, Paul (February 27, 1981). "Latest Times Sq. Proposal: Why It May Succeed: An Appraisal Renovation of Times Tower Proposed". The New York Times. p. B4. ISSN 0362-4331. ProQuest 121804824.

- ^ Horsley, Carter B. (July 1, 1981). "42d St. Plan Would Add Towers, Theaters and 'Bright Lights': Plans for 42d St. Would Add Theaters and 'Bright Lights'". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on September 4, 2022. Retrieved August 5, 2022.

- ^ a b c Stern, Fishman & Tilove 2006, 684쪽.

- ^ Goldberger, Paul (December 21, 1983). "4 New Towers for Times Sq". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on September 4, 2022. Retrieved August 9, 2022.

- ^ Gottlieb, Martin (November 29, 1983). "Developer Seeks to Tear Down Times Sq. Tower". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 5, 2022. Retrieved August 5, 2022.

- ^ Spiegelman, Arthur (January 5, 1984). "Time's running out for this landmark". South China Morning Post. p. 15. ProQuest 1553940873.

- ^ Depalma, Anthony (July 11, 1984). "About Real Estate; One Times Square, Its Future Unsure, is Sold Again". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 5, 2022. Retrieved August 5, 2022.

- ^ Anderson, Susan Heller; Bird, David (June 15, 1984). "New York Day by Day". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on September 4, 2022. Retrieved August 12, 2022.

- ^ Anderson, Susan Heller; Dunlap, David W. (December 18, 1984). "New York Day by Day; Objections on Times Sq". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 12, 2022. Retrieved August 12, 2022.

- ^ Gottlieb, Martin (March 3, 1985). "Civic Groups Assail Makeup Of Times Tower Committee". The New York Times. p. 34. ISSN 0362-4331. ProQuest 111225579.

- ^ a b c Grant, Peter (May 3, 1993). "Ball could drop on One Times Sq. lender". Crain's New York Business. Vol. 9, no. 18. p. 4. ProQuest 219173143.

- ^ "Sign of the Times for NY Newsday". Newsday. January 17, 1986. p. 6. ISSN 2574-5298. Archived from the original on August 9, 2022. Retrieved August 9, 2022.

- ^ Kennedy, Shawn G. (March 12, 1986). "Real Estate; Times Sq. Tower's Renewal". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 9, 2022. Retrieved August 9, 2022.

- ^ Goldberger, Paul (August 15, 1986). "An Appraisal; Times Sq. Bell Tower: the Wrong Centerpiece". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 9, 2022. Retrieved August 9, 2022.

- ^ Lueck, Thomas J. (July 2, 1988). "Reprieve for a Famed Tower on Times Sq". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on September 4, 2022. Retrieved August 5, 2022.

- ^ Robbins, Jim (June 8, 1988). "Pictures: New State-Of-The-Art Facilities For No. 1 Times Square Structure". Variety. Vol. 331, no. 7. p. 7. ISSN 0042-2738. ProQuest 1438491962.

- ^ McCain, Mark (April 9, 1989). "Commercial Property: Times Sq. Signage; A Mandated Comeback for the Great White". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 10, 2022. Retrieved August 9, 2022.

- ^ a b Wax, Alan J. (March 14, 1992). "1 Times Square in Bankruptcy". Newsday. p. 15. ISSN 2574-5298. Archived from the original on September 4, 2022. Retrieved August 9, 2022.

- ^ "Sony to Polish Image with Video Display for Times Square". Wall Street Journal. October 12, 1990. p. B4B. ISSN 0099-9660. ProQuest 398189556.

- ^ Ramirez, Anthony (October 11, 1990). "The Media Business: Advertising - Addenda; Sony to Help Make Times Square Brighter". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 9, 2022. Retrieved August 9, 2022.

- ^ Howe, Marvine (March 13, 1994). "Neighborhood Report: Midtown; For Times Square Couch Potatoes . . ". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 9, 2022. Retrieved August 9, 2022.

- ^ a b Ravo, Nick (March 14, 1992). "Times Square Landmark Files in Bankruptcy". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 5, 2022. Retrieved August 5, 2022.

- ^ Grant, Peter (June 7, 1993). "N.Y., feds make foreclosure less taxing". Crain's New York Business. Vol. 9, no. 23. p. 13. ProQuest 219143472.

- ^ Martin, Douglas (December 30, 1994). "Times Sq. Flash: ***ZIPPER SAVED***". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 9, 2022. Retrieved August 9, 2022.

- ^ "Pearson will keep 'zipper' running at Times Square". Wall Street Journal. December 30, 1994. p. C6. ISSN 0099-9660. ProQuest 398558205.

- ^ Lambert, Bruce (January 8, 1995). "Neighborhood Report: Midtown; The 'Zipper' Is Speaking a New Language". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 12, 2022. Retrieved August 12, 2022.

- ^ "Bank Buys Building Where the Ball Drops". The New York Times. January 26, 1995. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 12, 2022. Retrieved August 12, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e Bagli, Charles V. (June 19, 1997). "Tower in Times Sq., Billboards and All, Earns 400% Profit". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on July 7, 2017. Retrieved September 28, 2021.

- ^ a b "Wrangle kills plan for US Madame Tussaud's". South China Morning Post. March 29, 1995. p. 65. ProQuest 1535995762.

- ^ Lueck, Thomas J. (March 23, 1995). "Madame Tussaud's Loses Bidding War and Drops Times Sq. Plan". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 12, 2022. Retrieved August 12, 2022.

- ^ Levi, Vicki Gold; Heller, Steven (2004). Times Square Style: Graphics from the Great White Way. New York: Princeton Architectural Press. p. 9. ISBN 9781568984902. Archived from the original on August 5, 2022. Retrieved September 16, 2020.

- ^ Brill, Louis M. "Signage in the crossroads of the world". SignIndustry. Archived from the original on January 16, 2013. Retrieved January 15, 2013.

- ^ Holusha, John. "Times Square Signs: For the Great White Way, More Glitz". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on October 4, 2013. Retrieved January 15, 2013.

- ^ "Dow Jones taking over news 'zipper'". Portsmouth Daily Times. Associated Press. June 10, 1995. p. B8. Archived from the original on February 16, 2013. Retrieved January 20, 2013.

- ^ "Dow Jones will operate Times Square 'zipper' sign". Wall Street Journal. June 9, 1995. p. A5. ISSN 0099-9660. ProQuest 398448932.

- ^ Chen, David W. (May 6, 1997). "Times Sq. Sign Turns Corner Into Silence". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 9, 2022. Retrieved August 9, 2022.

- ^ Lueck, Thomas J. (May 17, 1996). "Less Glitter on Times Square: No More Jumbotron". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on October 3, 2009. Retrieved August 9, 2022.

- ^ a b c d Collins, Glenn (January 18, 1996). "The Media Business: Advertising; How do you get your message across among the Times Square throng? Try turning up the steam". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on December 21, 2013. Retrieved August 9, 2022.

- ^ a b Grant, Peter (October 17, 1996). "Warner zips up deal". New York Daily News. p. 760. ISSN 2692-1251. Archived from the original on September 28, 2021. Retrieved September 28, 2021.

- ^ "Warner Bros. Said to Eye Store Site in Times Square". Women's Wear Daily. Vol. 172, no. 84. October 31, 1996. p. 22. ProQuest 1445768894.

- ^ Johnson, Kirk (November 16, 1996). "Bugs Bunny Is New Tenant At 1 Times Sq". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on September 28, 2021. Retrieved September 28, 2021.

- ^ Muschamp, Herbert (April 7, 1997). "A Chance for an Architect to Let His Imagination Run Free". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 12, 2022. Retrieved August 12, 2022.

- ^ Cramer, Ned (May 1997). "Times Square Striptease" (PDF). Journal of the American Institute of Architects. Vol. 86. p. 49.

- ^ Alva, Marilyn (December 1, 1997). "Germans leading influx of foreign-borne money". Crain's New York Business. Vol. 13, no. 48. p. 23. ProQuest 219155738.

- ^ a b Pristin, Terry (March 12, 2008). "A Homecoming for a Former Times Square Fixture". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 5, 2022. Retrieved August 5, 2022.

- ^ Pristin, Terry (April 21, 1998). "Metro Business; 1 Times Square Store For Warner Brothers". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 12, 2022. Retrieved August 12, 2022.

- ^ Moin, David (April 21, 1998). "Warner Bros, To Cut Loose In Its Times Square Store". Women's Wear Daily. Vol. 175, no. 75. p. 8. ProQuest 1445681456.

- ^ Herszenhorn, David M. (April 26, 1998). "With Bugs's Debut, It's Toons Square". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 12, 2022. Retrieved August 12, 2022.

- ^ Goodnough, Abby (December 29, 1998). "Here Comes 2000, With Sponsors, Too; Official Products in the Right Place: Millennial Partying in Times Sq". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on April 22, 2022. Retrieved August 12, 2022.

- ^ MacFarquhar, Neil (March 20, 1999). "After Sign Falls in Wind, City Orders Others Moved". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 12, 2022. Retrieved August 12, 2022.

- ^ Bagli, Charles V. (July 12, 2001). "Bugs Bunny Is Losing His Times Square Home in October". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on September 28, 2021. Retrieved September 28, 2021.

- ^ "Warner Bros. Studio Stores to Close". The Los Angeles Times. July 7, 2001. p. 42. Archived from the original on September 28, 2021. Retrieved September 28, 2021.

- ^ Muto, Sheila (December 31, 2003). "Plots & Ploys". Wall Street Journal. p. B.6. ISSN 0099-9660. ProQuest 398911570.

- ^ Bagli, Charles V. (June 8, 2002). "Sweet on Times Square, Hershey Is to Open Store". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on July 25, 2022. Retrieved August 12, 2022.

- ^ Wilgoren, Jodi (July 13, 2003). "Business; In the Urban 7-Eleven, the Slurpee Looks Sleeker". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 12, 2022. Retrieved August 12, 2022.

- ^ Ramirez, Anthony (August 20, 2004). "Slab of Building Facade Falls, Injuring 2 People in Times Square". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 12, 2022. Retrieved August 12, 2022.

- ^ a b c Velsey, Kim (May 6, 2022). "One Times Square, Long Empty, Will Now Bring the Billboards Inside". Curbed. Archived from the original on June 16, 2022. Retrieved August 5, 2022.

- ^ "What's Really Inside". The Village Voice. March 7, 2006. Archived from the original on December 30, 2012. Retrieved January 15, 2013.

- ^ Power, Denise (March 3, 2006). "J.C. Penney Experience Pops With Technology". Women's Wear Daily. Vol. 191, no. 46. p. 22. ProQuest 231110770.

- ^ Jonas, Ilaina (November 21, 2007). "Walgreens to return to New York's Times Square". Reuters. Archived from the original on August 5, 2022. Retrieved August 5, 2022.

- ^ "Walgreens returns to 1 Times Square". Real Estate Weekly. May 14, 2008. Archived from the original on June 2, 2013. Retrieved August 5, 2022.

- ^ a b Elliott, Stuart (November 20, 2008). "An Ad Network in Times Square". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 12, 2022. Retrieved August 12, 2022.

- ^ "Walgreens opens doors in Times Square". Drug Store News. Vol. 30, no. 15. December 8, 2008. pp. 1, 8. ProQuest 204759199.

- ^ Collins, Glenn (May 24, 2008). "How to Stand Out in Times Square? Build a Bigger and Brighter Billboard". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on December 25, 2013. Retrieved August 9, 2022.

- ^ a b c Chen, Jackson (September 28, 2017). "Times Sq. Museum Aims To Steer Tourists Away From 'Elmos and Topless Women'". DNAinfo New York. Archived from the original on September 28, 2017. Retrieved September 29, 2017.

- ^ a b c d Chaffin, Joshua (May 6, 2022). "New York icon is reinvented as a 21st century 'interactive portal'". Financial Times. Archived from the original on August 6, 2022. Retrieved August 6, 2022.

- ^ a b "MTA to Transform 42 St Shuttle to Provide Better Service, Fully Accessible Crosstown Transit Connection". mta.info. Metropolitan Transportation Authority. August 2, 2019. Archived from the original on August 2, 2019. Retrieved August 2, 2019.

- ^ Ricciulli, Valeria (August 2, 2019). "MTA will overhaul century-old 42nd Street shuttle". Curbed NY. Archived from the original on August 2, 2019. Retrieved August 2, 2019.

- ^ Gartland, Michael (August 2, 2019). "42nd Street shuttle to get facelift; three-year project starts Aug. 16". New York Daily News. ISSN 2692-1251. Archived from the original on August 2, 2019. Retrieved August 2, 2019.

- ^ Nessen, Stephen (May 17, 2022). "New Times Square subway entrance includes an elevator — and the largest mosaic in the system". gothamist.com. Archived from the original on May 18, 2022. Retrieved May 18, 2022.

- ^ "MTA unveils new Times Square subway entrance". ABC7 New York. May 16, 2022. Archived from the original on May 17, 2022. Retrieved May 19, 2022.

- ^ a b Rebong, Kevin (January 29, 2019). "New York's most viewed building is getting a facelift". The Real Deal New York. Archived from the original on August 5, 2022. Retrieved August 5, 2022.

- ^ "Landlord to redevelop most viewed building in the world". Crain's New York Business. January 29, 2019. Archived from the original on October 19, 2021. Retrieved August 5, 2022.

- ^ Lo, Jasper K. (June 30, 2019). "Big, bold, wild and fun – Times Square billboards entertain a digital world". New York Daily News. ISSN 2692-1251. Archived from the original on November 8, 2019. Retrieved November 24, 2019.

- ^ Campos, Guy (August 20, 2019). "350-foot high LED wall relaunched in New York". AV Magazine. Archived from the original on August 6, 2020. Retrieved November 19, 2019.

- ^ Young, Michael (May 19, 2019). "One Times Square's 300-Foot-Long LED Screen Nearly Completed, in Times Square". New York YIMBY. Archived from the original on February 16, 2022. Retrieved November 15, 2020.

Another significant part of the exterior that was removed was the "zipper." This was the first of its kind in the world to display moving words for almost 90 years and was placed near the base of the tower

- ^ Beling, Sarah (April 7, 2022). "From Satan's Circus to Glittering Ball Drops to Walgreens — the Evolution of One Times Square". W42ST. Archived from the original on September 2, 2022. Retrieved September 2, 2022.

- ^ a b Adcroft, Patrick (May 6, 2022). "One Times Square to undergo $500 million renovation". Spectrum News NY1 New York City. Archived from the original on August 5, 2022. Retrieved August 5, 2022.

- ^ a b Novini, Rana; Smith, Romney (May 6, 2022). "NYC Mayor Eric Adams Announces $500M Times Square Redevelopment". NBC New York. Archived from the original on June 9, 2022. Retrieved August 5, 2022.

- ^ Dilakian, Steven (May 13, 2022). "Jamestown Lands $425M for One Times Square Redevelopment". The Real Deal New York. Archived from the original on August 2, 2022. Retrieved August 9, 2022.

- ^ Young, Celia (May 12, 2022). "Jamestown Snags $425M for One Times Square Redevelopment". Commercial Observer. Archived from the original on August 9, 2022. Retrieved August 9, 2022.

- ^ a b "Billboard Removal and Transformation of One Times Square Progresses in Midtown, Manhattan". New York YIMBY. June 16, 2022. Archived from the original on June 20, 2022. Retrieved August 5, 2022.

- ^ Garber, Nick (August 1, 2022). "New Times Square Scaffolding Lets Criminals Corner Tourists: Lawsuit". Midtown-Hell's Kitchen, NY Patch. Archived from the original on August 21, 2022. Retrieved August 21, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e "Intricate Work of Decoration; Designing Exterior Details of New Times Building. Regard Must Be Had for Both Color and Architectural Features – Preparing the Stone and Terra Cotta". The New York Times. December 20, 1903. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on July 17, 2020. Retrieved July 17, 2020.

- ^ a b c Landau & Condit 1996, 309쪽.

- ^ 뉴욕 타임즈 빌딩 부록 1905, 페이지 BS3.

- ^ a b Dunlap, David W. (April 24, 2015). "1905 - Times Building Is the Tallest in the City (With a Big Asterisk)". The New York Times. Archived from the original on October 30, 2020. Retrieved August 6, 2022.

- ^ "New York's Lofty Office Buildings: the Tallest and the Narrowest Now Being Completed in New York-- Wonderful Feats of Construction". The Construction News. Vol. 18, no. 25. December 17, 1904. p. 436. ProQuest 128400674.

- ^ a b c 뉴욕 타임즈 빌딩 부록 1905, 페이지 BS8.

- ^ a b c d e f g 뉴욕 타임즈 빌딩 부록 1905, 페이지 BS21.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Materials Used in the New York Times Building". The Construction News. Vol. 19, no. 13. April 1, 1905. p. 233. ProQuest 128409982.

- ^ a b c d 뉴욕 타임즈 빌딩 부록 1905, 페이지 BS23.

- ^ a b c Bein, Arthur G. (February 16, 1910). "Famous Prototypes of New York Towers". The American Architect. Vol. 97, no. 1782. p. 81. ProQuest 124670436.

- ^ "Problems That Come With Skyscrapers; Interior Irregularities Must Be Hidden by Outward Symmetry. Difficulties of This Sort Met in the New Times Building – Why a Tower Replaced a Dome". The New York Times. November 22, 1903. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 8, 2022. Retrieved August 8, 2022.

- ^ "Old Times Tower Will Be Enclosed By Marble Panels". The New York Times. August 2, 1964. p. 249. ISSN 0362-4331. ProQuest 115884348.

- ^ a b c d e "Sub-surface Problems in Structural Work; Some Facts About the Unseen Part of The Times Building. How Solid Rock is Made Stronger – How "Sand Cushions," Are Formed – Solving Problems of Ventilation". The New York Times. November 15, 1903. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 6, 2022. Retrieved August 6, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e "Foundations of the New Times Building; Structure One of Interesting Details Below the Curb Line. Cast Steel Bases for Columns – Protection Against Dampness and Corosion – "Sand Cushions" to Prevent Vibration". The New York Times. October 11, 1903. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 6, 2022. Retrieved August 6, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e Lawrence, Charles H. (June 16, 1906). "Structural Problems in the New York Times Building". The Construction News. Vol. 21, no. 24. p. 463. ProQuest 128405015.

- ^ 건축기록 1903, 페이지 330.

- ^ 건축 기록 1903, 페이지 330–331.

- ^ a b c d Landau & Condit 1996, 313쪽.

- ^ Landau & Condit 1996, pp. 312–313.

- ^ a b c "Notable Edition Marks Times Building Opening; Story of Great Structure Told in Special Supplement". The New York Times. December 31, 1904. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 8, 2022. Retrieved August 8, 2022.

- ^ a b c "Illustrations: the "Times" Building, Longacre Square, New York, N. Y.". The American Architect and Building News. Vol. 87, no. 1536. June 3, 1905. p. 179. ProQuest 124648830.

- ^ a b c d "Floor Space Division in Big Structures; Interior Structural Details in the New Times Building. Partitions Now a Matter of Utility, Not of Strength – No Exposed Columns – Laying the Floor Arches". The New York Times. December 6, 1903. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 6, 2022. Retrieved August 6, 2022.

- ^ a b c "Wind-bracing in New Times Building; Fiercest Gales Will Have No Terrors for the Structure. Three Types of Diagonal Strengthening Will Give Great Stability – Other Details". The New York Times. October 18, 1903. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on July 18, 2020. Retrieved July 17, 2020.

- ^ a b c "Interior of the New Times Building; Decorative Features to be Prominent in the New Structure. How the Great Foundations Will Add to the Strength of the Upper Portion – Unusual Facilities for Light". The New York Times. October 25, 1903. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 7, 2022. Retrieved August 7, 2022.

- ^ "Arcade to Be Feature in the Times Building; Lively Business Thoroughfare to be Made Under Ground. Booths to Flank the Corridors Leading to the Subway Station – Show Windows Along the Platform". The New York Times. January 17, 1904. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on July 17, 2020. Retrieved July 17, 2020.

- ^ "Times Sq. Subway Arcade Shut, Making a Belated End of Stores". The New York Times. July 2, 1967. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on July 15, 2022. Retrieved July 15, 2022.

- ^ Dunlap, David W. (March 28, 2004). "1904-2004; Crossroads of the Whirl". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 10, 2017. Retrieved August 12, 2022.

- ^ "Underground Room in New Times Building; Press Facilities Sixty-five Feet Below the Street. A Month Needed to Set Up Delicate Machinery – Area Below Ground – Handling the Papers". The New York Times. January 24, 1904. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 7, 2022. Retrieved August 7, 2022.

- ^ a b c d 뉴욕 타임즈 빌딩 부록 1905, 페이지 BS22.

- ^ Landau & Condit 1996, 311쪽.

- ^ 뉴욕 타임즈 빌딩 부록 1905, 페이지 BS6.

- ^ a b c "Interior Plans of New Times Building; Location Will Insure Abundance of Natural Light. Arrangement of Windows One of the Problems That Has Come with the Modern Skyscraper". The New York Times. December 27, 1903. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 7, 2022. Retrieved August 7, 2022.

- ^ a b Barron, James (December 30, 2009). "When Party Is Over, the Ball Lands Here". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on January 25, 2022. Retrieved August 9, 2022.

- ^ Bousquette, Isabelle (December 30, 2021). "The New Year's Eve Ball Will Drop, Covid or Not, if John Trowbridge Has His Way". Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Archived from the original on June 11, 2022. Retrieved December 30, 2021.

- ^ Balkin, Adam (December 30, 2003). "Technology Helps Times Square New Year's Eve Ball Drop Run Smoothly". NY1. Archived from the original on June 9, 2013. Retrieved April 15, 2012.

- ^ a b "How Skyscrapers Get Heat and Pure Air; Novel Devices Shown in These Details of New Times Building. Immense Chambers for Filtering Air -Heating Plant Will Use Nearly Sixteen Miles of Pipe". The New York Times. January 3, 1904. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 8, 2022. Retrieved August 8, 2022.

- ^ "Electricity's Uses in the Times Building; To Operate Over One Hundred Different Appliances". The New York Times. January 10, 1904. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 7, 2022. Retrieved August 7, 2022.

- ^ "Electricity in a Modern Newspaper Building". The Electrical Age. Vol. 32, no. 3. March 1, 1904. p. 139. ProQuest 574279299.

- ^ a b "Improvement Shown in Elevator Equipment; Electric Cars in Times Building Will Embody New Principles". The New York Times. February 7, 1904. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 7, 2022. Retrieved August 7, 2022.

- ^ 뉴욕 타임즈 빌딩 부록 1905, 페이지 BS20.

- ^ 뉴욕 타임즈 빌딩 부록 1905, pp. BS20–BS21.

- ^ "The Times Building Safest, Says Croker; Fire Department Makes Test of Standpipes". The New York Times. April 17, 1905. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 8, 2022. Retrieved August 8, 2022.

- ^ "Mayor Giuliani Lights Up ITT's Electronic Display Sign in Times Square". Government of New York City. Archived from the original on March 20, 2013. Retrieved January 14, 2013.

- ^ Lewine, Edward (November 15, 1998). "Neighborhood Report: Times Square; No Remote Can Fix This Screen". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on October 4, 2013. Retrieved August 9, 2022.

- ^ Bagli, Charles V. (June 19, 1997). "Tower in Times Sq., Billboards and All, Earns 400% Profit". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 14, 2012. Retrieved January 14, 2013.

- ^ "Times Square's hot spots provide bang for the buck". Crain's New York Business. Vol. 21, no. 20. May 16, 2005. p. 12. ProQuest 219121568.

- ^ Brown, Eliot (December 26, 2012). "Ads, Not Tenants, Make Times Square". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on January 11, 2013. Retrieved January 14, 2013.

- ^ Hellman, Peter (May 19, 1997). "Bright Lights, Big Money". New York Magazine. Vol. 30, no. 19. p. 48. ISSN 0028-7369. Archived from the original on April 7, 2022. Retrieved September 16, 2020.

- ^ a b Lueck, Thomas J. (June 18, 1998). "Metro Business; Discover Is Sponsor For Year 2000 Event". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 6, 2016. Retrieved August 9, 2022.

- ^ Brian (October 13, 2006). "News Corp Takes Over Times Sq. Screen". TV Newser. Archived from the original on January 16, 2011.

- ^ "Sony Corporation of America and News Corporation Partner to Program Digital Space in One of the World's Most Recognized Advertising Locations—Times Square in New York City" (Press release). Sony Corporation of America. July 13, 2010. Retrieved November 23, 2022.

- ^ Elliott, Stuart (December 3, 2007). "Back in Times Square, Toshiba Stands Tall". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on December 27, 2016. Retrieved August 9, 2022.

- ^ a b Tracy, Thomas (May 30, 2018). "Construction worker rescued after he falls behind giant Times Square Toshiba sign". New York Daily News. ISSN 2692-1251. Archived from the original on January 27, 2021. Retrieved August 9, 2022.

- ^ Temistokle, Eddie (December 7, 2009). "Make Your Way to the Big Screen: Toshiba Introduces 'I'm on TV' Feature to Toshiba Vision in Times Square" (PDF) (Press release). Toshiba America. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 23, 2010.

- ^ "Cash-strapped Toshiba bids farewell to Times Square and 'Sazae-san'". The Japan Times Online. November 22, 2017. ISSN 0447-5763. Archived from the original on December 7, 2020. Retrieved December 5, 2017.

- ^ "Changing times: Toshiba's New York billboard goes dark". Nikkei Asian Review. Archived from the original on June 5, 2018. Retrieved June 5, 2018.

원천

- "The Evolution of a Skyscraper". Architectural Record. Vol. 14. 1903. hdl:2027/hvd.32044039466818 – via HathiTrust.

- Landau, Sarah; Condit, Carl W. (1996). Rise of the New York Skyscraper, 1865–1913. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-07739-1. OCLC 32819286.

- "New York Times Building Supplement". The New York Times. January 1, 1905. ISSN 0362-4331.

- "Architectural Aspect of Times Building; Advantages offered by the Times Square Site – Abundance of Light Gave Opportunity for Apparent Massiveness – The Tower as the Triumph of the Building – A Success in Scale – The Chief Charm of the Structure, Its Color, Achieved by a Stroke of Architectural Good Fortune". The New York Times. January 1, 1905. ISSN 0362-4331.

- "Construction of Times Building; Elimination of the Fire Risks – "A Stone Fence Under Water" – Weights of Materials – Chronology of the Work – A Startling Record of Strikes and of Time Lost by Each Trade – List of Accidents Incidental to a Large Operation". The New York Times. January 1, 1905. ISSN 0362-4331.

- "Equipment of Times Building; Electric Elevators with Highest Rise and Costly Control – A Smokestack 389 Feet High – Highest Lift of Water in America – Cleaning by Vacuum Process – Artificial Illumination – Filtering 250 Gallons a Minute". The New York Times. January 1, 1905. ISSN 0362-4331.

- Stern, Robert A. M.; Fishman, David; Tilove, Jacob (2006). New York 2000: Architecture and Urbanism Between the Bicentennial and the Millennium. New York: Monacelli Press. ISBN 978-1-58093-177-9. OCLC 70267065. OL 22741487M.

외부 링크

Wikimedia Commons의 One Times Square 관련 미디어

Wikimedia Commons의 One Times Square 관련 미디어- 공식 홈페이지