안토니 블링컨

Antony Blinken안토니 블링컨 | |

|---|---|

2021년 공식 초상화 | |

| 제71대 미국 국무장관 | |

| 가임사무소 2021년1월26일 | |

| 대통령 | 조 바이든 |

| 대리 | 웬디 셔먼 빅토리아 눌런드 (연기) |

| 앞에 | 마이크 폼페이오 |

| 미국 제18대 국무부 부장관 | |

| 재직중 2015년 1월 9일 ~ 2017년 1월 20일 | |

| 대통령 | 버락 오바마 |

| 앞에 | 윌리엄 J. 번스 |

| 승계인 | 존 설리번 |

| 제26대 국가안보보좌관 | |

| 재직중 2013년 1월 20일 ~ 2015년 1월 9일 | |

| 대통령 | 버락 오바마 |

| 지도자 | 수잔 라이스 |

| 앞에 | 데니스 맥도너 |

| 승계인 | 에이브릴 헤인스 |

| 미국 부통령 국가안보보좌관 | |

| 재직중 2009년 1월 20일 ~ 2013년 1월 20일 | |

| 부통령 | 조 바이든 |

| 앞에 | 존 한나 |

| 승계인 | 제이크 설리번 |

| 신상명세부 | |

| 태어난 | 안토니 존 블링컨 1962년 4월 16일 용커스, 뉴욕, 미국 |

| 정당 | 민주적 |

| 배우자. | (m. 2002) |

| 아이들. | 2 |

| 부모 | |

| 친척들. | |

| 교육 | |

안토니 존 블링컨(Antony John Blinken, 1962년 4월 16일 ~ )은 2021년 1월 26일부터 미국의 제71대 국무장관을 역임한 미국의 공무원이자 외교관입니다.그는 앞서 버락 오바마 대통령 시절인 2013년부터 2015년까지 국가안보보좌관, 2015년부터 2017년까지 국무부 부장관을 역임했습니다.[1]

클린턴 행정부 시절 블링컨은 1994년부터 2001년까지 국무부와 국가안보회의 고위직을 역임했습니다.그는 2001년부터 2002년까지 전략 국제 연구 센터의 선임 연구원이었습니다.2002년부터 2008년까지 상원 외교위원회 민주당 간사장을 지내면서 2003년 이라크 침공을 주창했습니다.[2]그는 오바마-바이든 대통령직 전환을 조언하기 전에 조 바이든의 2008년 대선 캠페인의 외교 정책 고문이었습니다.

2009년부터 2013년까지 블링컨은 대통령의 부보좌관과 부통령의 국가안보보좌관을 역임했습니다.오바마 행정부에서 재임하는 동안, 그는 아프가니스탄, 파키스탄, 그리고 이란의 핵 프로그램에 대한 미국의 정책을 만드는 것을 도왔습니다.[3][4]공직을 떠난 후 블링컨은 컨설팅 회사인 West Executive Advisors를 공동 설립하면서 민간 부문으로 진출했습니다.블링컨은 바이든의 2020년 대통령 선거 운동을 위한 외교 정책 고문으로 먼저 정부에 복귀한 후, 2021년 1월 26일 상원이 그를 임명했습니다.

어린시절과 교육

블링컨은 1962년 4월 16일 뉴욕 용커스에서 유대인 부모 주디스(프렘)와 도널드 M 사이에서 태어났습니다. 나중에 헝가리 주재 미국 대사를 지낸 블링컨.[5][6][7]그의 외조부모는 헝가리 유대인이었습니다.[8]블링큰의 삼촌인 앨런 블링큰은 벨기에 주재 미국 대사를 역임했습니다.[9][10]그의 친할아버지 모리스 헨리 블링컨은 이스라엘의 경제적 생존 가능성을 연구한 초기 후원자였고,[11] 그의 증조부는 이디시 작가 메이르 블링컨이었습니다.[12]

블링컨은 1971년까지 뉴욕에 있는 돌턴 학교에 다녔습니다.[6]그 후 그는 어머니 주디스, 사무엘 피사르와 함께 파리로 이주했는데, 그녀는 블링컨과 이혼한 후 결혼했습니다.인사청문회에서 블링컨은 폴란드에 있는 자신의 학교의 900명의 아이들 중 유일한 홀로코스트 생존자였던 의붓아버지에 대한 이야기를 했습니다.피사르는 나치의 죽음의 행진 중 숲으로 난입한 후 미군 탱크에서 피난처를 발견했습니다.[13][14]블링컨은 파리에서 에콜 잔느 마누엘을 다녔습니다.[15]

블링컨은 1980년부터 1984년까지 하버드 대학교에 다녔고,[16] 그곳에서 사회학을 전공했습니다.그는 하버드 학생 신문 하버드 크림슨(The Harvard Crimson)을 공동 편집하고 [5][17][18]시사에 관한 많은 기사를 썼습니다.[19][16]하버드를 졸업한 후 블링컨은 뉴 리퍼블릭에서 약 1년간 인턴으로 일했습니다.[6][16]그는 1988년[20][21] 컬럼비아 로스쿨에서 J.D.를 취득하고 뉴욕시와 파리에서 변호사 일을 했습니다.[22]블링컨은 1988년 미국 대통령 선거에서 민주당 후보였던 마이클 듀카키스를 위한 기금을 마련하기 위해 아버지와 함께 일했습니다.[5]

블링컨은 그의 논문 "동맹 대 동맹: 미국, 유럽, 그리고 시베리아 파이프라인 위기"에서 시베리아 파이프라인 위기 동안 소련에 외교적 압력을 가하는 것은 미국과 유럽 사이의 강력한 관계를 유지하는 것보다 미국의 이익에 덜 중요하다고 주장했습니다.[23]앨리 대 앨리는 블링컨의 학부 논문을 바탕으로 헨리 키신저를 인터뷰했습니다.[17][24]

경력초기

클린턴과 부시 행정부

블링컨은 지난 20년 동안 두 정부에서 고위 외교 정책 직책을 맡아왔습니다.[5]그는 1994년부터 2001년까지 국가안전보장회의(NSC) 직원이었습니다.[25]1994년부터 1998년까지 블링컨은 대통령의 특별 보좌관이자 전략 기획 수석 이사, 연설문 작성 NSC 수석 이사를 역임했습니다.[26]1999년부터 2001년까지, 그는 유럽과 캐나다 문제를 위한 대통령의 특별 보좌관이자 수석 이사였습니다.[27]

블링컨은 2003년 미국 주도의 이라크 침공을 지지했습니다.[2][28]2002년, 그는 2008년까지 근무했던 상원 외교 위원회의 참모 이사로 임명되었습니다.[25]블링컨은 당시 상원 외교위원장이었던 조 바이든 당시 상원의원을 도와 미국의 이라크 침공에 대한 바이든의 지지를 공식화했고, 블링컨은 이라크 침공 투표를 "힘든 외교를 위한 투표"라고 특징 지었습니다.[29]

미국의 이라크 침공과 점령 후 몇 년 동안 블링컨은 상원에서 바이든이 이라크에 민족 또는 종파적 선을 따라 나뉘어진 세 개의 독립 지역을 설립하는 제안을 공식화하는 것을 도왔습니다: 이라크 쿠르디스탄뿐만 아니라 남쪽의 "시아스탄", 북쪽의 "수니스탄".이라크 총리가 분할안에 반대한 이라크뿐 아니라 국내에서도 이 제안이 압도적으로 부결됐습니다.[30]

그는 또한 전략 국제 연구 센터의 선임 연구원이었습니다.2008년, 블링컨은 조 바이든의 대통령 선거 운동을 위해 일했고,[5] 오바마-바이든 대통령직 인수팀의 일원이었습니다.[31]

오바마 행정부

2009년부터 2013년까지 블링컨은 대통령의 부보좌관과 부통령의 국가안보보좌관을 역임했습니다.이 자리에서 그는 아프가니스탄, 파키스탄 그리고 이란의 핵 프로그램에 대한 미국의 정책을 만드는 것을 도왔습니다.[3][4]블링컨은 2013년 1월 20일 데니스 맥도너의 뒤를 이어 국가안보보좌관으로 취임했습니다.[32]

2014년 11월 7일, 오바마 대통령은 퇴임하는 윌리엄 J. 번스의 후임으로 블링컨을 차관으로 지명할 것이라고 발표했습니다.[33]2014년 12월 16일, 블링컨은 55 대 38의 투표로 상원으로부터 국무부 부장관으로 임명되었습니다.[34]

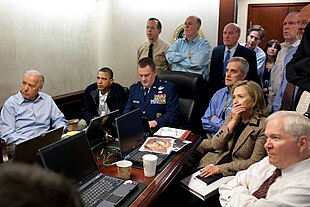

오사마 빈 라덴을 죽이기로 한 오바마의 2011년 결정에 대해 블링컨은 "지도자가 내린 이보다 더 용기 있는 결정을 본 적이 없습니다."[35]라고 말했습니다.2013년 프로필에는 그를 "시리아 정책 초안 작성에 있어 정부의 핵심 역할 중 한 명"으로 묘사했으며,[5] 이를 위해 그는 공개적인 얼굴 역할을 했습니다.[36]블링컨은 2014년 우크라이나 혁명의 여파로 러시아 연방에 의한 크림 반도 합병에 대한 오바마 행정부의 대응을 이끌어내는 데 영향력이 있었습니다.[37][38]

블링컨은 2011년 리비아에[36] 대한 군사 개입과 시리아 반군에 대한 무기 공급을 지지했습니다.[39]그는 2016년 터키 쿠데타 시도를 비난하고 민주적으로 선출된 터키 정부와 그 기관들에 대한 지지를 표명했지만, 2016년부터 현재까지 터키에서 일어난 숙청에 대해서도 비판했습니다.[40]2015년 4월 블링컨은 예멘에 대한 사우디아라비아 주도의 개입을 지지하는 목소리를 냈습니다.[41]그는 "그 노력의 일환으로 무기를 신속하게 전달하고 정보 공유를 늘렸으며 사우디 작전 센터에 공동 조정 계획 셀을 설립했다"[42]고 말했습니다.

블링컨은 2014년 이스라엘-가자 분쟁 동안 이스라엘의 철돔 요격 미사일 무기고를 보충하기 위해 바이든과 함께 미국 자금을 요청했습니다.[43]2015년 5월, 블링컨은 미얀마의 무슬림 박해를 비판하고 반이슬람 입법의 위험성에 대해 미얀마의 지도자들에게 경고하면서 로힝야 무슬림들은 "시민권으로 가는 길을 가져야 한다"고 말했습니다.[44]신분이 없는 것에서 오는 불확실성은 사람들을 떠나게 만드는 것 중 하나입니다."[45]

2015년 6월, 블링컨은 9개월 전 미국 주도의 연합군이 이슬람국가에 반대하는 캠페인을 시작한 이후 미국 주도의 대(對)[46]이슬람국가 공습으로 1만 명 이상의 ISIL 전사가 사망했다고 주장했습니다.

펜 바이든 센터

2017년부터 2019년까지 펜실베이니아 대학교 싱크탱크인 펜 바이든 센터(Penn Biden Center)의 상무이사를 역임했습니다.[47]이 기간 동안 그는 외교 정책과 트럼프 행정부에 관한 여러 기사를 발표했습니다.

민간부문

웨스트이그제큐티브 어드바이저

2017년 블링컨은 정치 전략 자문 회사인 웨스트 이그제큐티브 어드바이저스를 미셸 플로르노이, 세르히오 아기레, 니틴 차다와 함께 공동 설립했습니다.[48][49]웨스트이그제큐티브의 고객사로는 구글의 직소, 이스라엘의 인공지능 회사 윈드워드, 공군과 720만 달러의 계약을 체결한 감시용 드론 제조업체 쉴드 AI,[50] '포춘 100종' 등이 있습니다.[51]포린폴리시에 따르면 이 회사의 고객층은 "방위산업, 사모펀드, 헤지펀드" 등입니다.[52]블링큰은 웨스트이그제큐티브로부터 거의 120만 달러의 보상금을 받았습니다.[53]

The Intercept와의 인터뷰에서 플로르노이는 WestExec의 역할을 실리콘밸리 기업과 국방부 및 법 집행부 간의 관계를 촉진하는 것으로 설명했습니다.[54] 플로르노이와 다른 사람들은 WestExec을 Kissinger Associates와 비교했습니다.[54][55]

파인아일랜드 캐피털 파트너스

블링컨을 비롯해 바이든 인수팀 멤버인 미셸 플로노이 전 국방부 고문, 로이드 오스틴 국방부 장관 등은 웨스트이그제큐티브의 전략적 파트너인 사모펀드 파인아일랜드 캐피털 파트너스의 파트너입니다.[56][57][58]파인 아일랜드의 회장은 뱅크 오브 아메리카에 매각되기 전 메릴린치의 최종 회장인 존 테인입니다.[59]블링컨은 2020년 8월 외교 정책 고문으로서 바이든 캠페인에 참여하기 위해 파인 아일랜드에서 휴가를 떠났습니다.[57]그는 바이든 행정부의 직책이 확정되면 파인아일랜드의 지분을 처분하겠다고 말했습니다.[58]

바이든의 대선 캠페인 마지막 기간 동안 파인 아일랜드는 특수 목적 인수 회사(SPAC)를 위해 2억 1,800만 달러를 모금했으며, 이 회사의 안내서는 "국방, 정부 서비스 및 항공 우주 산업"과 코로나19 구제에 투자하기 위해 투자했습니다(9월에 미국 SEC에 처음 제출하여 11월에 최종 확정됨).2020년 13일)는 정부가 팬데믹을 해결하기 위해 민간 계약자들에게 눈을 돌리면서 수익성이 좋을 것으로 예상했습니다.[57]Thain은 다른 파트너들의 "접근성, 네트워크 및 전문성" 때문에 그들을 선택했다고 말했습니다.[50]

2020년 12월 뉴욕 타임즈 기사에서 블링컨을 포함한 웨스트이그제큐티브 교장, 파인아일랜드 고문, 바이든 행정부 내 서비스 간의 잠재적인 이해 상충에 대한 질문을 제기하면서 비평가들은 모든 웨스트이그제큐티브/파인아일랜드 금융 관계의 완전한 공개, 입찰한 회사의 소유권 지분 매각을 요구했습니다.정부 계약 또는 기존 계약을 즐기고 블링큰과 다른 사람들이 이전 고객에게 유리할 수 있는 결정으로부터 스스로를 거부한다는 보장.[50]

블링큰은 외교 관계[60] 위원회의 일원이며 이전에 CNN의 글로벌 업무 분석가였습니다.[61][62]

국무장관

지명 및 확정

블링컨은 바이든의 2020년 대선 캠페인을 위한 외교 정책 고문이었습니다.[63]2020년 11월 22일, 블룸버그 통신은 바이든이 블링컨을 국무장관 후보로 지명했다고 보도했습니다.[64]이 보도들은 나중에 뉴욕타임즈와 다른 매체들에 의해 확증되었습니다.[30][65][64]11월 24일 바이든의 국무장관 후보로 발표된 블링컨은 "우리는 세계의 모든 문제를 혼자 해결할 수 없으며 다른 나라들과 함께 일할 필요가 있습니다."라고 말했습니다.[66]그는 앞서 2020년 9월 AP통신과의 인터뷰에서 "민주주의는 전 세계적으로 후퇴하고 있으며 불행하게도 대통령이 매일 기관과 가치관, 국민들에게 2대 4로 데려다 주기 때문에 국내에서도 후퇴하고 있습니다"라고 말했습니다.[67]

2021년 1월 19일 상원 외교위원회가 시작되기 전 블링컨의 인사청문회.그의 지명은 1월 25일 위원회에서 15 대 3의 투표로 확정되었습니다.[68]1월 26일 블링컨은 78 대 22의 투표로 상원 전체에 확정되었습니다.[1]블링컨은 그날 늦게 국무장관 취임 선서를 했습니다.[69]그렇게 함으로써, 그는 1992년과 1993년 각각 로렌스 이글버거와 워렌 크리스토퍼에 이어 국무장관을 지낸 세 번째 전직 국무차관이 되었습니다.[70][71]

재직기간

미얀마

2021년 1월 31일, 블링컨은 2021년 미얀마 쿠데타를 비난하고 정부 관리와 시민 사회 지도자들의 구금에 심각한 우려를 표명하며 즉각 석방을 요구했습니다.[72]그는 "미국은 민주적으로 선출된 정부의 회복을 요구하면서 버마 사람들에게 폭력을 행사하는 사람들에 대해 계속해서 단호한 조치를 취할 것"이라고 말했습니다.[73]

아프가니스탄

2021년 2월, 블링컨은 아슈라프 가니 대통령과 대화를 나누며 탈레반 이슬람 반군과의 아프간 평화 협상을 지지하고 "정의롭고 지속적인 정치적 해결과 영구적이고 포괄적인 휴전"을 포함하는 평화 협정에 대한 미국의 약속을 거듭 강조했습니다.[74]

블링컨 장관은 바이든 행정부의 2021년 아프가니스탄 주둔 미군 철수 발표에 따라 지난 4월 15일 카불을 예고 없이 방문해 미군과 외교 인사들을 만났습니다.[75]그는 아프가니스탄에서 철수하기로 결정한 것은 중국과 코로나19 팬데믹에 자원을 집중하기 위해서라고 말했습니다.[76]그는 미국의 아프가니스탄 철군에 이어 국무장관직 사퇴 요구에 직면했습니다.[77][78][79][80]

2021년 8월 블링컨은 미군과 연합군이 아프가니스탄에서 철수하기 시작한 후 2021년 5월 시작된 탈레반의 공세와 1975년 혼란스러운 미국의 사이공 이탈로 악화된 아프가니스탄 상황을 비교하며 "우리는 20년 전에 하나의 임무를 가지고 아프가니스탄에 갔습니다., 그리고 그 임무는 9/11에 우리를 공격한 사람들을 상대하는 것이었고 우리는 그 임무에 성공했습니다."[81]

아프리카

2021년 2월 블링켄은 에티오피아 북부 티그레이 지역의 인종청소를 비난하고 에리트레아군과 다른 전투원들의 즉각적인 철수를 요구했습니다.[82][83]

바이든 행정부가 지난 행정부 시절 제정된 모로코와 이스라엘의 정상화 협정을 계속 검토하는 가운데 블링컨 장관은 1975년 모로코에 합병된 분쟁 지역인 서사하라에 대한 모로코의 주권 인정이 당장 번복되지는 않을 것이라는 입장을 고수했습니다.그는 내부 논의를 통해 양국간 관계 개선을 지지하고 서사하라에 유엔 특사를 임명하는 데 시급함을 표명했습니다.[84][85]

2023년 3월, 그는 에티오피아 정부와 티그레이 반군 사이의 티그레이 전쟁으로 경색된 미국과 에티오피아의 관계를 정상화하기 위해 아디스아바바에서 아비 아메드 에티오피아 총리를 만났습니다.[86]

남미

블링큰은 베네수엘라 임시 대통령 후안 과이도와 대화를 나눴는데, 그는 바이든 행정부가 니콜라스 마두로가 아닌 국가의 원수로 계속 인정할 것입니다.[87]

아시아

블링컨 장관은 3월 15일 로이드 오스틴 국방장관과 함께 처음으로 도쿄와 서울을 방문했고, 그 동안 그는 중국에게 강제와 침략에 대해 경고했습니다.[88][89]그는 또한 중국 정부가 위구르족에 대한 대량학살을 자행하고 있다고 비난했습니다.[90]

2021년 7월, 바이든 행정부는 중국을 전 세계적인 사이버 스파이 캠페인으로 비난했는데, 블링컨은 이 캠페인이 "우리의 경제와 국가 안보에 큰 위협이 된다"고 말했습니다.[91]

2021년 4월 말, 블링컨은 2019년 홍콩 시위에서 그들의 역할에 대한 홍콩 민주화 운동가 지미 라이, 앨버트 호, 리척얀 등의 선고를 "정치적 동기에 의한" 결정이라고 비난했습니다.[92][93]

2022년 5월 블링컨은 "중국은 경제적, 기술적, 군사적, 외교적 수단뿐만 아니라 국제 질서의 다른 비전을 발전시키려는 의도를 가지고 있는 유일한 국가입니다."라고 말했습니다.[94]러시아-우크라이나 전쟁에서 중립적이라는 중국의 주장을 일축하고 중국이 러시아를 지지하고 있다고 비난했습니다.[95]

2023년 6월, 블링컨은 베이징을 방문하는 동안 시진핑 중국 국가주석을 만났습니다.국무부의 이 자료에 따르면 블링컨 장관은 "오산의 위험을 줄이기 위해 모든 범위의 문제에 걸쳐 개방된 의사소통 채널을 유지하는 것의 중요성을 강조했다"며 "우리는 강력하게 경쟁하겠지만 미국은 그 경쟁을 책임감 있게 관리하여 양국 관계가 악화되지 않도록 할 것임을 분명히 했다"고 말했습니다.갈등에 빠졌습니다."[96]

G7 회의

2021년 5월, 블링컨은 런던과 레이캬비크를 방문하여 각각 G7 외무장관 회의와 북극 이사회 장관 회의를 열었습니다.[97][98]블링컨 장관은 키예프에서 볼로디미르 젤렌스키 대통령과 드미트로 쿨레바 외무장관과의 회담에서 "러시아의 침략"에 대항하는 우크라이나의 주권과 영토 보전에 대한 지지를 재확인했습니다.[99]블링컨 장관은 이스라엘과 팔레스타인의 분쟁이 계속되는 동안 이스라엘의 방어권에 대한 지지를 표명하면서도 동예루살렘에 있는 팔레스타인 가족들을 집에서 쫓아내는 것은 폭력과 보복의 발생을 더욱 고조시킬 수 있는 행동들 중 하나라고 경고했습니다.[100][101]그는 유엔 안전보장이사회와 함께 휴전을 전적으로 고수할 것을 촉구하고 팔레스타인 민간인들에 대한 인도적 지원의 즉각적인 필요성을 강조하면서 두 국가간 해결책의 필요성을 거듭 강조했습니다.[102]휴전 이후 5월 25일 블링컨의 예루살렘 방문과 함께 유엔과 인권 의사, 구호단체 직원, 언론인들이 제공한 식량과 의료품의 가자 지구로의 이동이 허용되었습니다.[103]

유럽

노르트 스트림 2 천연가스 파이프라인 완공에 이어 노르트 스트림 AG와 그 최고경영자 마티아스 워니그에 대한 제재를 면제하기로 한 결정은 의회의 비판을 받았습니다.[104]블링컨 장관은 이 조치가 미국의 이익에 실용적이고 실용적이라고 주장하며, 그렇지 않으면 유럽 관계에 역효과를 가져올 것이라고 말했습니다.[104]2021년 6월, 블링컨은 콘월에서 열린 제47차 G7 정상회의, 브뤼셀에서 열린 제31차 나토 정상회의, 그리고 제네바에서 블라디미르 푸틴 대통령과의 정상회담에 참석하기 위해 바이든과 함께 여행했습니다.[105]블링큰과 바이든은 모두 미국과 러시아의 관계가 최저점에 있었고, 더 예측 가능한 관계가 주요 우선순위로 남아 있다는 것을 인정했습니다.[106]다만 러시아 정부가 2020년 대선 개입이나 태양풍 사이버 공격, 알렉세이 나발니 독살·감금 등 적대 행위를 계속하기로 결정하면 추가적인 징벌 조치가 시행될 것이라고 예고했습니다.[106]블링컨 장관은 정상회담 후 공동 기자회견을 포기하기로 한 행정부의 결정에 대해 "가장 효과적인 방법"이라며 "희귀한 관행이 아니다"고 설명했습니다.[107]

블링컨은 그해 말 유럽연합(EU) 각료들과 함께 브뤼셀을 방문해 유럽연합(EU) 각료들과 함께 대서양을 횡단하는 동맹을 강화하려는 바이든 행정부의 결의를 강조했습니다.

블링컨은 유럽연합과의 무역 관계를 장려하기 위해 2021년 창설된 이후 무역기술위원회의 공동 의장을 맡고 있습니다.[108]

러시아-우크라이나 전쟁

2022년 1월 블링컨은 러시아와의 국경 긴장 속에서 동유럽 국가를 지원하기 위해 우크라이나에 무기 공급을 승인했습니다.[109][110]2월 11일 블링컨은 2022년 동계 올림픽이 끝나기 전에 러시아의 우크라이나 침공 가능성에 대해 공개적으로 경고했습니다.[111]2월 13일, 블링컨은 키예프 주재 미국 대사관에서 대부분의 직원을 대피시킨 것은 "신중한 일"이라고 말했습니다.[112]2022년 9월 블링컨은 미국이 우크라이나 군이 러시아에 점령된 우크라이나 영토를 탈환하는 것을 돕겠다고 약속했습니다.[113]그는 블라디미르 푸틴 대통령의 핵무기 사용 위협에 대해 "러시아가 스스로 엉망진창이 된 것은 [독재] 체제에서 푸틴 대통령이 잘못된 일을 하고 있다고 효과적으로 말할 사람이 없기 때문"이라고 비판했습니다.[114]

블링컨 장관은 러시아와 우크라이나의 전쟁에서 중립을 결정한 국가들에 대해 "이번 공격에 관한 한 중립을 취하기가 상당히 어렵습니다.명백한 침략자가 있습니다.분명한 피해자가 있습니다."[115]

그는 2022년 러시아 동원에 대해 언급하면서 동원된 러시아 민간인들이 "푸틴이 전쟁에 던지려 하는 캐넌포더"로 취급되고 있다고 말했습니다.[116]2022년 10월 21일, 블링컨은 미국의 시도에도 불구하고 러시아가 외교적 방법으로 우크라이나 전쟁을 끝낼 의지가 없다고 말했습니다.[117]블링컨 장관은 중국의 평화 제안에 대해 "세계는 중국이나 다른 어떤 나라의 지원을 받는 러시아가 독자적인 조건으로 전쟁을 동결하려는 어떤 전술적 움직임에도 속아서는 안 된다"고 의문을 제기했습니다.[118]2023년 6월, 그는 "현재의 라인을 단순히 제자리에 얼리는 중단 사격"을 거부했습니다.[119]2023년 7월, 그는 우크라이나에 집속탄을 공급하기로 한 바이든의 결정을 옹호했습니다.[120]

해외에 억류중인 미국인들.

블링컨과 바이든 행정부는 해외에 부당하게 수감된 미국인들을 처리했다는 비판을 받아왔습니다.중동에 있는 미국인 억류자 가족들은 블링컨 장관과의 통화가 끊긴 것에 대해 화가 났습니다.[121]2022년 7월 블링큰은 세르게이 라브로프와 만나 폴 윌란(보안 책임자)과 브리트니 그리너의 석방을 보장하기 위한 죄수 교환을 논의했습니다.[122]블링컨은 해외에 구금된 사랑하는 사람들이 있는 가족들의 연합체인 Bring Our Familys Home 캠페인을 만났습니다.[123]

블링컨, 대통령 인질특사 로저 D의 업적과 함께. 카르스텐스는 트레버 리드, 대니 펜스터, 바커 나마지, 시트고 식스 전체, 오스만 칸, 매튜 존 히스, 마크 프레리치스, 호르헤 알베르토 페르난데스 등 해외에 부당하게 억류되거나 인질로 억류된 12명이 넘는 미국인들의 석방을 협상해 왔습니다.

대외정책직

뉴욕 타임즈는 2020년 민주당 대선 후보 조 바이든의 외교 정책 고문으로서 블링컨을 "바이든의 정책 문제에 귀를 기울이고 있다"고 묘사했습니다.[124]그의 외교 정책 입장은 매파적인 것으로 묘사되어 왔습니다.[125]블링컨 장관은 "바이든 장관은 이스라엘에 대한 군사적 지원을 이스라엘 정부의 합병이나 다른 결정과 결부시키지 않을 것"이라고 주장했습니다.[126]블링컨 장관은 트럼프 행정부가 중재한 이스라엘과 바레인, 아랍에미리트 간의 정상화 합의를 높이 평가했습니다.[127][128]2020년 10월 28일 블링컨은 바이든 행정부가 미국의 이익과 가치를 증진시키기 위해 미국과 사우디아라비아의 관계에 대한 전략적 검토에 착수할 것임을 재확인했습니다.[129]2021년 1월, 블링컨은 바이든 행정부가 이스라엘 주재 미국 대사관을 예루살렘에 유지하고 이스라엘-팔레스타인 분쟁에 대한 두 국가의 해결책을 모색할 것이라고 말했습니다.[130]블링컨 장관은 이란에 대한 비핵화 제재를 지속하는 것에 찬성하며, 이를 "다른 지역에서의 이란의 잘못된 행동에 대한 강력한 헤지 수단"이라고 설명했습니다.[127]트럼프 전 대통령이 이란과의 국제 핵 합의에서 미국을 탈퇴한 것을 비판하며 '더 길고 강한' 핵 협상에 대한 지지를 표명했습니다.[131][132]블링컨 장관은 이란의 핵무기 획득을 막기 위한 군사적 개입도 배제하지 않았습니다.[133][134]

블링컨 장관은 트럼프 행정부가 중국의 핵심 전략 목표를 진전시키는 데 도움을 주는 것에 대해 비판적인 입장을 보여왔습니다.그는 "[트럼프는] 미국의 동맹을 약화시켜 중국이 채워야 할 세계의 공백을 남겼고, 우리의 가치를 버리고 중국에게 신장에서 홍콩까지의 인권과 민주주의를 짓밟을 청신호를 주었다"고 말했습니다.[135]하지만, 그는 또한 전 대통령 행정부의 공격적인 접근을 비난했고, 중국을 세계의 지배를 추구하는 "기술 독재 국가"로 규정했습니다.[136][137]그는 홍콩에서 온 정치 난민들을 환영하고 싶다는 뜻을 내비쳤고, 바이든 행정부의 대만 방어에 대한 약속은 "절대적으로 견딜 것"이며, 중국이 대만에 대해 군사력을 사용하는 것은 "그들의 중대한 실수"가 될 것이라고 말했습니다.[137]블링컨 장관은 또 중국이 신장 북서부 지역에서 위구르 이슬람교도들과 다른 소수민족들을 상대로 대량학살과 반인륜 범죄를 자행하고 있다고 지적했습니다.[138]블링컨 장관은 트럼프 전 대통령의 중국과의 1단계 무역협상을 '실패'로 규정했습니다.[139]그는 중국과 완전히 분리하는 것은 비현실적이라며 "대만과의 경제적 유대 강화"에 대한 지지를 표명했습니다.[139][140]

블링컨 장관은 지중해 동부 안보 및 에너지 파트너십 법과 관련해 그리스, 이스라엘, 키프로스 간의 굳건한 관계에 미국의 관심을 표명하고 "동맹국처럼 행동하지 않는" 확장주의 터키가 제기하는 위협을 인정했습니다.[141]그는 레제프 에르도안 터키 대통령이 "키프로스의 두 국가 해결책"을 촉구한 데 대해 바이든 행정부가 키프로스의 통일에 전념하고 있다며 반대했습니다.[40][142]블링컨 장관은 에르도안 정부를 제재하는 방안도 검토하겠다는 뜻을 내비쳤습니다.[143]블링컨 장관은 북대서양조약기구(NATO·나토)가 캅카스 지역 국가인 그루지야에 문호를 개방하는 것을 지지한다는 입장을 재확인하고 나토 회원국들이 '러시아의 침략'으로부터 보다 효과적으로 보호받고 있다는 주장을 제기했습니다.[144]

블링컨 장관은 배치된 전략핵탄두의 수를 제한하기 위해 러시아와 신전략무기감축조약을 연장하는 것을 지지한다고 밝혔습니다.[30][145]블링켄은 바이든 행정부가 나고르노카라바흐 분쟁 지역을 둘러싼 아제르바이잔과 아르메니아의 2020년 나고르노카라바흐 전쟁으로 인해 아제르바이잔에 대한 안보 지원을 "검토"할 것이라며 "안보 지원 제공"에 대한 지지의 목소리를 높였습니다.[146]

블링컨 장관은 영국의 유럽연합(EU) 탈퇴에 반대하며 미국의 이익에 불리한 결과를 초래하는 '완전 엉망진창'이라고 비난했습니다.[147][148]블링컨 장관은 압델 파타 엘 시시 대통령 시절 이집트에서 인권 침해가 감지되는 것에 대해 우려를 표명했습니다.[149]그는 "외국 외교관들을 만나는 것은 범죄가 아니다"라며 이집트 인권 이니셔티브 직원 3명을 체포한 것을 비난했습니다.평화적으로 인권을 옹호하는 것도 아닙니다."[150]블링컨 장관은 2021년 탈레반이 카불을 점령한 후 선포한 아프가니스탄 이슬람 토후국을 언급하며 미국은 테러 단체를 수용하거나 기본적 인권을 보장하지 않는 어떤 정부도 인정하지 않을 것이라고 말했습니다.[151]

개인생활

블링켄은 유대인입니다.[152]2002년 블링큰과 에반 라이언은 워싱턴 D.C.에 있는 홀리 트리니티 가톨릭 교회에서 랍비와 사제의 주례로 종교간 결혼식을 올렸습니다.[20][5]그들에게는 두 아이가 있습니다.[153]블링컨은 불어에 유창합니다.[154]그는 기타를 연주하고 애블린켄[155](Ab Lincoln)이라는 별칭으로 스포티파이에서 3곡의 노래를 들을 수 있습니다.[156]

참고 항목

간행물

- Blinken, Antony J. (1987). Ally versus Ally: America, Europe, and the Siberian Pipeline Crisis. New York: Praeger. ISBN 0-275-92410-6. OCLC 14359172.[5]

- Blinken, Antony J. (2001). "The False Crisis Over the Atlantic". Foreign Affairs. 80 (3): 35–48. doi:10.2307/20050149. JSTOR 20050149.

- Blinken, Antony J. (June 2002). "Winning the War of Ideas". The Washington Quarterly. 25 (2): 101–114. doi:10.1162/01636600252820162. ISSN 0163-660X. S2CID 154183240.

- Blinken, Antony J. (December 2003). "From Preemption to Engagement". Survival. 45 (4): 33–60. doi:10.1080/00396330312331343576. ISSN 0039-6338. S2CID 154077314.

참고문헌

- ^ a b "Senate confirms Antony Blinken as 71st secretary of state". AP NEWS. January 26, 2021. Archived from the original on January 26, 2021. Retrieved January 26, 2021.

- ^ a b Glueck, Katie; Kaplan, Thomas (January 12, 2020). "Joe Biden's Vote for War". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 18, 2020. Retrieved November 23, 2020.

- ^ a b "Senate Confirms Antony "Tony" Blinken '88 as Secretary of State". Columbia Law School. December 17, 2014. Archived from the original on September 19, 2020. Retrieved November 26, 2020.

- ^ a b Sanger, David E. (November 7, 2014). "Obama Makes His Choice for No. 2 Post at State Department". The New York Times. Archived from the original on February 20, 2015. Retrieved February 3, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Horowitz, Jason (September 20, 2013). "Antony Blinken steps into the spotlight with Obama administration role". The Washington Post. p. C1. ProQuest 1432540846. Archived from the original on September 16, 2013. Retrieved September 28, 2013.

- ^ a b c "Antony 'Tony' Blinken". Jewish Virtual Library. 2013. Archived from the original on November 17, 2015. Retrieved November 16, 2015.

- ^ "Frehm – Blinken". The New York Times. December 7, 1957. Archived from the original on March 24, 2017. Retrieved November 23, 2020.

- ^ Andriotakis, Pamela (August 25, 1980). "Sam and Judith Pisar Meld the Disparate Worlds of Cage and Kissinger in Their Marriage". People. Archived from the original on November 23, 2020. Retrieved November 25, 2020.

- ^ Russell, Betsy Z. (November 23, 2020). "Why Biden's pick for Secretary of State has a name that's familiar in Idaho politics ..." Idaho Press. Archived from the original on November 29, 2020. Retrieved December 2, 2020.

- ^ Finnegan, Conor (November 24, 2020). "Who is Tony Blinken? Biden taps close confidante, longtime aide for secretary of state". ABC News. Archived from the original on December 2, 2020. Retrieved December 2, 2020.

- ^ "Maurice Blinken, 86; Early Backer of Israel". The New York Times. July 15, 1986. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on November 30, 2020. Retrieved January 23, 2021.

- ^ Briman, Shimon (November 30, 2020). "Yiddish and the Ukrainian–Jewish roots of the new U.S. Secretary of State". Translated by Marta D. Olynyk. Ukrainian Jewish Encounter. Archived from the original on January 9, 2021. Retrieved January 6, 2021.

- ^ Wisse, Ruth R. (February 2021). "A Tale of Five Blinkens". Commentary. Archived from the original on January 19, 2021. Retrieved January 23, 2021.

- ^ 2021년 1월 19일 안토니 J. 블링컨 국무장관 지명자가 미국 상원 외교위원회 앞에서 2021년 3월 4일 웨이백 머신에서 보관된 기록을 위한 성명서.

- ^ Bezioua, Céline. "Venue d'Antony Blinken à l'école" (in French). École Jeannine Manuel. Archived from the original on April 20, 2018. Retrieved August 8, 2020.

- ^ a b c Rodríguez, Jesús (January 11, 2021). "The World According to Tony Blinken – in the 1980s". Politico. Archived from the original on January 12, 2021. Retrieved January 12, 2021.

- ^ a b Uribe, Raquel Coronell; Griffin, Kelsey J. (December 7, 2020). "President-elect Joe Biden Nominates Harvard Affiliates to Top Executive Positions". The Harvard Crimson. Archived from the original on January 12, 2021. Retrieved December 7, 2020.

- ^ "Anthony J. Blinken". The Harvard Crimson. Archived from the original on December 10, 2016. Retrieved November 22, 2020.

- ^ Paumgarten, Nick (December 7, 2020). "A Dad-Rocker in the State Department". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on January 12, 2021. Retrieved December 9, 2020.

- ^ a b "WEDDINGS; Evan Ryan, Antony Blinken". The New York Times. March 3, 2002. Archived from the original on December 7, 2013. Retrieved September 28, 2013.

- ^ "Deputy Secretary of State Antony Blinken '88 Speaks at Annual D.C. Alumni Dinner". Columbia Law School. April 30, 2015. Archived from the original on September 18, 2020. Retrieved November 23, 2020.

- ^ Sorcher, Sara (July 17, 2013). "Antony Blinken, Deputy National Security Adviser". National Journal. Archived from the original on February 14, 2015.

- ^ Miller, Chris (December 3, 2020). "The Ghost of Blinken Past". Foreign Policy. Archived from the original on December 6, 2020. Retrieved December 5, 2020.

- ^ Guyer, Jonathan (June 8, 2023). "I Crashed Henry Kissinger's 100th-Birthday Party". Intelligencer. Retrieved June 8, 2023.

- ^ a b Gaouette, Nicole; Hansler, Jennifer; Atwood, Kylie (November 24, 2020). "Biden picks loyal lieutenant to lead mission to restore US reputation on world stage". CNN. Archived from the original on November 25, 2020. Retrieved November 26, 2020.

- ^ "Antony J. Blinken". United States Department of State. Archived from the original on November 23, 2020. Retrieved November 26, 2020.

- ^ Gallucci, Robert (2009). Instruments and Institutions of American Purpose. United States: Aspen Institute. p. 112. ISBN 9780898435016. Archived from the original on November 23, 2020. Retrieved January 20, 2015.

- ^ Fordham, Evie (November 23, 2020). "Biden secretary of state pick Blinken criticized over Iraq War, consulting work". Fox News. Archived from the original on November 23, 2020. Retrieved November 23, 2020.

- ^ Johnson, Jake (November 27, 2020). "As Biden taps Blinken as Secretary of State, critics denounce support for invasions of Iraq, Libya". Salon. Archived from the original on December 1, 2020. Retrieved December 5, 2020.

- ^ a b c Jakes, Lara; Crowley, Michael; Sanger, David E. (November 23, 2020). "Biden Chooses Antony Blinken, Defender of Global Alliances, as Secretary of State". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on November 23, 2020. Retrieved December 5, 2020.

- ^ LaMonica, Gabe (December 17, 2014). "Blinken confirmed by Senate as Kerry's deputy at State". CNN. Archived from the original on February 20, 2015. Retrieved February 3, 2015.

- ^ Nakamura, David; Horwitz, Sari (January 25, 2013). "Obama taps McDonough as chief of staff, says goodbye to longtime adviser Plouffe". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on December 8, 2020. Retrieved June 26, 2021.

- ^ "Obama nominates his adviser Tony Blinken as Deputy Secretary of State". Reuters. Archived from the original on November 8, 2014. Retrieved November 7, 2014.

- ^ "U.S. Senate: U.S. Senate Roll Call Votes 113th Congress – 2nd Session". senate.gov. Archived from the original on September 25, 2018. Retrieved January 8, 2019.

- ^ Mann, Jim (2012). The Obamians: The Struggle Inside the White House to Redefine American Power. New York: Viking Press. p. 313. ISBN 9780670023769. OCLC 1150993166.

- ^ a b Allen, Jonathan (September 16, 2013). "Tony Blinken's star turn". Politico. Archived from the original on August 28, 2020. Retrieved November 23, 2020.

- ^ Gramer, Robbie; Detsch, Jack (November 23, 2020). "Biden's Secretary of State Pick Bodes Return to Normalcy for Weary Diplomats". Foreign Policy. Archived from the original on November 25, 2020. Retrieved November 25, 2020.

- ^ Zeleny, Jeff; Merica, Dan; Atwood, Kylie (November 22, 2020). "Biden poised to nominate Antony Blinken as secretary of state". CNN. Archived from the original on November 25, 2020. Retrieved November 25, 2020.

- ^ "W.H. defends plan to arm Syrian rebels". CNN. September 18, 2014. Archived from the original on October 19, 2017. Retrieved November 23, 2020.

- ^ a b "ABD yönetimine Türkiye açısından kritik isimler". Deutsche Welle (in Turkish). November 23, 2020. Archived from the original on December 1, 2020. Retrieved December 4, 2020.

- ^ "Yemen conflict: US boosts arms supplies for Saudi-led coalition". BBC News. April 7, 2015. Archived from the original on July 2, 2018. Retrieved November 23, 2020.

- ^ "US steps up arms for Saudi campaign in Yemen". Al Jazeera. April 8, 2015. Archived from the original on November 13, 2020. Retrieved November 23, 2020.

- ^ Magid, Jacob (November 24, 2020). "In tapping Blinken, Biden will be served by confidant with deep Jewish roots". The Times of Israel. Archived from the original on November 30, 2020. Retrieved December 3, 2020.

- ^ "Myanmar population control bill signed into law despite concerns it could be used to persecute minorities". ABC News. May 24, 2015. Archived from the original on March 12, 2018. Retrieved December 5, 2020.

- ^ "Myanmar should share responsibility for Rohingya crisis: US". Business Standard. May 23, 2015. Archived from the original on October 19, 2016. Retrieved December 5, 2020.

- ^ Mroue, Bassem (June 3, 2015). "U.S. official: Airstrikes killed 10,000 Islamic State fighters". USA Today. Archived from the original on December 6, 2020. Retrieved December 5, 2020.

- ^ Associated Press (January 29, 2023). "Classified docs probe pushes Biden think tank into spotlight". AP News. Retrieved September 1, 2023.

- ^ "Michèle Flournoy". WestExec Advisors. October 19, 2017. Archived from the original on November 15, 2020. Retrieved May 22, 2020.

- ^ "Our Team". WestExec Advisors. January 11, 2016. Archived from the original on May 10, 2020. Retrieved May 22, 2020.

- ^ a b c Lipton, Eric; Vogel, Kenneth P. (November 28, 2020). "Biden Aides' Ties to Consulting and Investment Firms Pose Ethics Test". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on November 28, 2020. Retrieved December 10, 2020.

- ^ Guyer, Jonathan (July 6, 2020). "How Biden's Foreign-Policy Team Got Rich". The American Prospect. Archived from the original on July 18, 2020. Retrieved July 21, 2020.

- ^ Detsch, Jack; Gramer, Robbie (November 23, 2020). "Biden's Likely Defense Secretary Pick Flournoy Faces Progressive Pushback". Foreign Policy. Archived from the original on November 25, 2020. Retrieved November 25, 2020.

- ^ Vogel, Kenneth P.; Lipton, Eric (January 2, 2021). "Washington Has Been Lucrative for Some on Biden's Team". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on January 12, 2021. Retrieved January 2, 2021.

- ^ a b Fang, Lee (July 22, 2018). "Former Obama Officials Help Silicon Valley Pitch the Pentagon for Lucrative Defense Contracts". The Intercept. Archived from the original on May 15, 2020. Retrieved May 22, 2020.

- ^ Shorrock, Tim (September 21, 2020). "Progressives Slam Biden's Foreign Policy Team". The Nation. Archived from the original on November 25, 2020. Retrieved November 25, 2020.

- ^ "Antony Blinken". Pine Island Capital Partners. Archived from the original on August 9, 2020. Retrieved May 22, 2020.

- ^ a b c Ackerman, Spencer; Markay, Lachlan; Schactman, Noah (December 8, 2020). "Firm Tied to Team Biden Looks to Cash In On COVID Response". The Daily Beast. Archived from the original on December 12, 2020. Retrieved December 10, 2020.

- ^ a b "The Revolving Door: Biden's National Security Nominees Cashed In on Government Service – and Now They're Back". Common Dreams. November 28, 2020. Archived from the original on November 29, 2020. Retrieved November 29, 2020.

- ^ "Team". Pine Island Capital Partners. Archived from the original on August 9, 2020. Retrieved May 22, 2020.

- ^ "Membership Roster". Council on Foreign Relations. Archived from the original on February 8, 2019. Retrieved November 23, 2020.

- ^ "Antony J. Blinken". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on November 23, 2020. Retrieved November 26, 2020.

- ^ "Tony Blinken – Spring 2017 Resident Fellow". University of Chicago Institute of Politics. 2017. Archived from the original on April 8, 2017. Retrieved April 8, 2017.

- ^ Hook, Janet; Wilkinson, Tracy (November 23, 2020). "Biden's longtime advisor Antony Blinken emerges as his pick for secretary of State". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on December 2, 2020. Retrieved December 6, 2020.

- ^ a b Pager, Tyler; Epstein, Jennifer; Mohsin, Saleha (November 22, 2020). "Biden to Name Longtime Aide Blinken as Secretary of State". Bloomberg News. Archived from the original on November 23, 2020. Retrieved November 22, 2020.

- ^ Herszenhorn, David M.; Momtaz, Rym (November 23, 2020). "9 things to know about Antony Blinken, the next US secretary of state". Politico. Archived from the original on November 24, 2020. Retrieved November 24, 2020.

- ^ Smith, David (November 24, 2020). "'A cabinet that looks like America': Harris hails Biden's diverse picks". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on November 24, 2020. Retrieved November 24, 2020.

- ^ Lee, Matthew (November 22, 2020). "Biden expected to nominate Blinken as secretary of state". AP News. Archived from the original on November 23, 2020. Retrieved December 6, 2020.

- ^ Zengerle, Patricia; Pamuk, Humeyra (January 26, 2021). "U.S. Senate expected to confirm Blinken as Secretary of State on Tuesday". Reuters. Archived from the original on January 26, 2021. Retrieved January 26, 2021.

- ^ Hansler, Jennifer (January 26, 2021). "Antony Blinken sworn in as Biden's secretary of state". CNN. Archived from the original on May 11, 2021. Retrieved January 27, 2021.

- ^ "Biographies of the Secretaries of State: Warren Minor Christopher (1925–2011)". U.S. Department of State. n.d. Archived from the original on December 5, 2018. Retrieved March 10, 2021.

- ^ "Biographies of the Secretaries of State: Lawrence Sidney Eagleburger (1930–2011)". U.S. Department of State. n.d. Archived from the original on December 5, 2018. Retrieved March 10, 2021.

- ^ "Top U.S. diplomat Blinken calls on Myanmar military leaders to release Suu Kyi, others". Reuters. February 1, 2021. Archived from the original on February 8, 2021. Retrieved February 11, 2021.

- ^ "U.S.'s Blinken vows 'firm action' against Myanmar military". Reuters. February 4, 2021. Archived from the original on May 21, 2021. Retrieved May 21, 2021.

- ^ "Blinken tells Ghani U.S. supports Afghanistan peace process – statement". Reuters. February 18, 2021. Archived from the original on March 18, 2021. Retrieved February 20, 2021.

- ^ Hansler, Jennifer (April 15, 2021). "Secretary of State Blinken visits Afghanistan day after US announces plans for withdrawal". CNN. Archived from the original on May 21, 2021. Retrieved May 21, 2021.

- ^ "U.S. Focus Shifting to China From Afghanistan, Blinken Says". Bloomberg. April 18, 202. Archived from the original on April 18, 2021.

- ^ "Secretary of State Antony Blinken needs to resign". New York Post. August 20, 2021. Archived from the original on February 13, 2023. Retrieved February 13, 2022.

- ^ "Blinken must resign". The Washington Times. Archived from the original on February 13, 2023. Retrieved February 13, 2022.

- ^ Chasmar, Jessica (September 13, 2021). "Multiple GOP congressmen tell Blinken to resign during heated Afghanistan hearing". Fox News. Archived from the original on April 14, 2023. Retrieved February 13, 2022.

- ^ ""Fatally Flawed": GOP congressman tells Blinken to resign as Afghanistan hearing heats up". Newsweek. September 13, 2021. Archived from the original on February 13, 2023. Retrieved February 13, 2022.

- ^ Choi, Joseph (August 15, 2021). "Blinken on Afghanistan: 'This is not Saigon'". The Hill. Archived from the original on August 18, 2021. Retrieved August 21, 2021.

- ^ "Top US diplomat decries 'ethnic cleansing' in Ethiopia's Tigray". Al Jazeera. March 10, 2021. Archived from the original on February 13, 2023. Retrieved April 14, 2023.

- ^ "The World's Deadliest War Isn't in Ukraine, But in Ethiopia". The Washington Post. March 23, 2022. Archived from the original on November 10, 2022. Retrieved April 14, 2023.

- ^ "Scoop: Biden won't reverse Trump's Western Sahara move, U.S. tells Morocco". Axios. April 30, 2021. Archived from the original on May 3, 2022. Retrieved April 14, 2023.

- ^ "Why Biden's Western Sahara policy remains under review". Al-Jazeera. June 13, 2021. Archived from the original on February 13, 2023. Retrieved April 14, 2023.

- ^ "Blinken praises Ethiopia on Tigray peace, no return to trade programme yet". Reuters. March 15, 2023.

- ^ "Secretary Blinken's Call with Venezuelan Interim President Guaidó". United States Department of State. Archived from the original on March 20, 2021. Retrieved March 19, 2021.

- ^ Nunley, Christian (March 10, 2021). "Pentagon chief, secretary of State announce first trips abroad as Biden looks to reset global relations". CNBC. Archived from the original on March 15, 2021. Retrieved March 16, 2021.

- ^ Pamuk, Humeyra; Takenaka, Kiyoshi; Park, Ju-min (March 17, 2021). "Blinken warns China against 'coercion and aggression' on first Asia trip". Reuters. Archived from the original on April 14, 2023. Retrieved April 13, 2021.

- ^ Toosi, Nahal (March 22, 2021). "U.S., allies announce sanctions on China over Uyghur 'genocide'". Politico. Archived from the original on April 29, 2021. Retrieved March 22, 2021.

- ^ "U.S. and allies accuse China of global hacking spree". Reuters. July 19, 2021. Archived from the original on February 13, 2023. Retrieved April 14, 2023.

- ^ Cheung, Eric (April 1, 2021). "Hong Kong court convicts media tycoon Jimmy Lai and other activists over peaceful protest". CNN. Archived from the original on April 1, 2021. Retrieved May 21, 2021.

- ^ "Sentencing of Hong Kong Pro-Democracy Activists for Unlawful Assembly". United States Department of State. Archived from the original on April 16, 2021. Retrieved April 16, 2021.

- ^ "Blinken warns China threat greater than Russia long term". Deutsche Welle. May 26, 2022. Archived from the original on April 3, 2023. Retrieved April 14, 2023.

- ^ "US's Blinken raises China's 'alignment with Russia' on Ukraine". Al Jazeera. July 9, 2022. Archived from the original on March 20, 2023. Retrieved April 14, 2023.

- ^ "Secretary Blinken's Visit to the People's Republic of China (PRC)". June 19, 2023. Retrieved June 19, 2023.

- ^ "Travel to United Kingdom and Ukraine, May 3–6, 2021". United States Department of State. Retrieved April 25, 2021.

- ^ "Travel to Denmark, Iceland, and Greenland, May 16–20, 2021". United States Department of State. Archived from the original on May 17, 2021. Retrieved May 17, 2021.

- ^ Hansler, Jennifer (May 6, 2021). "Blinken says US 'actively looking' at boosting security cooperation with Ukraine during trip to Kiev". CNN. Archived from the original on May 21, 2021. Retrieved May 21, 2021.

- ^ "The Latest: Netanyahu raps 'anarchy' of Jewish-Arab fighting". Associated Press. May 13, 2021. Archived from the original on May 13, 2021. Retrieved May 13, 2021.

- ^ Tidman, Zoe (May 28, 2021). "US 'warns Israeli leaders evicting Palestinians could spark war'". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on May 30, 2021. Retrieved June 1, 2021.

- ^ "Egyptian mediators try to build on Israel-Hamas ceasefire". Reuters. May 22, 2021. Archived from the original on May 22, 2021. Retrieved May 23, 2021.

- ^ Graham-Harrison, Emma; Borger, Julian (May 25, 2021). "'US to reopen Palestinian diplomatic mission in Jerusalem". The Guardian. Archived from the original on May 26, 2021. Retrieved May 27, 2021.

- ^ a b Zengerle, Patricia (June 7, 2021). "Blinken: U.S. able to mitigate Nord Stream 2 pipeline effects". Reuters. Archived from the original on June 24, 2021. Retrieved June 23, 2021.

- ^ Price, Ned (June 9, 2021). "Travel to the United Kingdom, Belgium, and Switzerland, June 9–15, 2021". Archived from the original on June 12, 2021. Retrieved June 9, 2021.

- ^ a b Clark, Joseph (June 13, 2021). "Blinken says U.S.-Russia relations at a low point going into summit". The Washington Times. Archived from the original on June 15, 2021. Retrieved June 15, 2021.

- ^ Price, Ned (June 13, 2021). "Secretary Antony J. Blinken with Chris Wallace of Fox News Sunday". Archived from the original on June 15, 2021. Retrieved June 15, 2021.

- ^ "EU Eyes May In-Person Meeting of U.S. Technology Council". Bloomberg.com. January 27, 2022. Archived from the original on May 18, 2022. Retrieved September 5, 2022.

- ^ "Blinken Authorizes Baltic Countries to Send US Weapons to Ukraine". VOA. January 22, 2022. Archived from the original on February 13, 2023. Retrieved January 30, 2022.

- ^ "US sends first military aid shipment to Ukraine amid Russia standoff". euronews. January 22, 2022. Archived from the original on March 15, 2023. Retrieved January 30, 2022.

- ^ "Blinken says Russia could invade Ukraine during Olympics". ABC News. February 11, 2022. Archived from the original on August 25, 2022. Retrieved April 14, 2023.

- ^ "Ukraine tensions: US defends evacuating embassy as Zelensky urges calm". BBC News. February 13, 2022. Archived from the original on February 13, 2022. Retrieved April 14, 2023.

- ^ "Blinken, in Kyiv, pledges to support Ukraine 'for as long as it takes'". The Washington Post. September 8, 2022. Archived from the original on February 13, 2023. Retrieved April 14, 2023.

- ^ "Blinken: US has told Russia to 'stop the loose talk' on nuclear weapons". The Hill. September 25, 2022. Archived from the original on February 13, 2023. Retrieved April 14, 2023.

- ^ "Antony Blinken Tried to Convince China to Reject Russia. It Went About as Well as You'd Expect". Mother Jones. July 9, 2022. Archived from the original on March 21, 2023. Retrieved April 14, 2023.

- ^ "U.S., Russian Defense Ministers Discuss Ukraine Invasion In Rare Phone Call". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. October 21, 2022. Archived from the original on February 13, 2023. Retrieved April 14, 2023.

- ^ "U.S. sees no evidence Russia is interested in ending Ukraine aggression - Blinken". Reuters. October 21, 2022. Archived from the original on February 13, 2023. Retrieved October 21, 2022.

- ^ "Putin welcomes China's controversial proposals for peace in Ukraine". The Guardian. March 21, 2023. Archived from the original on April 12, 2023. Retrieved April 14, 2023.

- ^ "Blinken says no Ukraine cease-fire without a peace deal that includes Russia's withdrawal". CNBC. June 3, 2023.

- ^ "Ukraine says cluster munitions will be 'game changer' against Russia". Politico. July 11, 2023.

- ^ "Anger as families of US detainees in Middle East left off Blinken call". the Guardian. July 5, 2022. Archived from the original on February 13, 2023. Retrieved July 29, 2022.

- ^ "Blinken says he 'pressed' Lavrov on release of US prisoners". www.aljazeera.com. Archived from the original on February 13, 2023. Retrieved July 29, 2022.

- ^ Atwood, Kylie; Hansler, Jennifer (June 23, 2022). "Families of unlawfully detained Americans left with mixed emotions after Blinken tried to reassure them in call CNN Politics". CNN. Archived from the original on February 13, 2023. Retrieved October 22, 2022.

- ^ Kaplan, Thomas (October 30, 2020). "Who Has Biden's Ear on Policy Issues? A Largely Familiar Inner Circle". The New York Times. p. A23. Archived from the original on November 24, 2020. Retrieved December 1, 2020.

- ^ "Biden's Foreign Policy Picks Are from the Hawkish National Security Blob. That is a Bad Sign". November 23, 2020.

- ^ Dershowitz, Toby; Kittrie, Orde (June 21, 2020). "Biden blasts BDS: Why it matters". The Jerusalem Post. Archived from the original on July 16, 2020. Retrieved July 16, 2020.

- ^ a b Kornbluh, Jacob (October 28, 2020). "Tony Blinken's Biden spiel". Jewish Insider. Archived from the original on November 21, 2020. Retrieved November 23, 2020.

- ^ Lacy, Akela (November 18, 2020). "On Arms Sales to Dictators and the Yemen War, Progressives See a Way In With Biden". The Intercept. Archived from the original on November 22, 2020. Retrieved November 23, 2020.

- ^ Magid, Jacob (October 29, 2020). "Top Biden foreign policy adviser 'concerned' over planned F-35 sale to UAE". The Times of Israel. Archived from the original on November 5, 2020. Retrieved November 23, 2020.

- ^ "Biden's State pick backs two-state solution, says US embassy stays in Jerusalem". The Times of Israel. Agence France-Presse. January 19, 2021. Archived from the original on January 20, 2021. Retrieved January 20, 2021.

- ^ "Biden to nominate Antony Blinken as US secretary of state". Al Jazeera. November 23, 2020. Archived from the original on November 24, 2020. Retrieved November 23, 2020.

- ^ Lake, Eli (January 22, 2021). "Biden's First Foreign Policy Blunder Could Be on Iran". Bloomberg. Archived from the original on January 22, 2021. Retrieved January 23, 2021.

- ^ "Backing 'every' option against Iran, Blinken appears to nod at military action". The Times of Israel. October 14, 2021. Archived from the original on December 15, 2021. Retrieved April 14, 2023.

- ^ "Blinken Declines to Rule Out Military Option Should Iran Nuclear Talks Fail". Haaretz. October 31, 2021. Archived from the original on December 15, 2021. Retrieved April 14, 2023.

- ^ Galloway, Anthony (November 23, 2020). "Biden's pick for the next secretary of state is Australia's choice too". Brisbane Times. Archived from the original on November 24, 2020. Retrieved November 23, 2020.

- ^ Barnes, Julian E.; Jakes, Lara; Steinhauer, Jennifer (January 20, 2021). "In Confirmation Hearings, Biden Aides Indicate Tough Approach on China". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on January 20, 2021. Retrieved January 20, 2021.

- ^ a b Fromer, Jacob (January 20, 2021). "Top US diplomat nominee says Trump's China approach was right, tactics wrong". South China Morning Post. Archived from the original on January 20, 2021. Retrieved January 20, 2021.

- ^ "U.S. secretary of state nominee Blinken sees strong foundation for bipartisan China policy". Reuters. January 19, 2021. Archived from the original on January 22, 2021. Retrieved January 23, 2021.

- ^ a b Shalal, Andrea (September 22, 2020). "Biden adviser says unrealistic to 'fully decouple' from China". Reuters. Archived from the original on September 25, 2020. Retrieved November 25, 2020.

- ^ Thomas, Ken (November 23, 2020). "Joe Biden Picks Antony Blinken for Secretary of State". The Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. ProQuest 2462827440. Archived from the original on November 26, 2020. Retrieved November 26, 2020.

- ^ "US-Greece security relationship key to American interests in East Med, says Blinken". Kathimerini. Archived from the original on January 22, 2021. Retrieved January 23, 2021.

- ^ @ABlinken (October 27, 2020). "We regret calls by Turkish President Erdogan and Turkish Cypriot leader Tatar for a two-state solution in Cyprus. Joe Biden has long expressed support for a bizonal, bicommunal federation that ensures peace and prosperity for all Cypriots" (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- ^ "US secretary of state nominee Blinken says Turkey not acting like an ally". Kathimerini. January 20, 2021. Archived from the original on January 20, 2021. Retrieved January 23, 2021.

- ^ 블링큰 장관 지명자는 2021년 1월 22일 시빌 조지아 웨이백 머신에서 보관된 조지아에 나토 문이 계속 열려 있을 것이라고 말했습니다.

- ^ Pifer, Steven (December 1, 2020). "Reviving nuclear arms control under Biden". Brookings Institution. Archived from the original on December 1, 2020. Retrieved December 3, 2020.

- ^ "Incoming US Secretary of State Antony Blinken voices support for Armenia and Republic of Artsakh". Public Radio of Armenia. January 22, 2021. Archived from the original on January 22, 2021. Retrieved January 23, 2021.

- ^ Borger, Julian (November 23, 2020). "Antony Blinken: Biden's secretary of state nominee is sharp break with Trump era". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on November 24, 2020. Retrieved November 24, 2020.

- ^ Colson, Thomas (November 3, 2020). "Joe Biden's Secretary of State pick Tony Blinken said Brexit was like a dog being run over by a car and a 'total mess'". Business Insider. Archived from the original on June 14, 2021. Retrieved June 15, 2021.

- ^ Dettmer, Jamie (November 24, 2020). "Egyptian Suspects in Murder of Italian Student Likely to Face In-Absentia Trial". Voice of America. Archived from the original on November 24, 2020. Retrieved November 25, 2020.

- ^ "Biden aide Blinken voices concern about rights group in Egypt". Reuters. November 20, 2020. Archived from the original on November 27, 2020. Retrieved November 25, 2020.

- ^ Iqbal, Anwar (August 16, 2021). "US to recognise Taliban only if they respect basic rights, says Blinken". DAWN.COM. Archived from the original on August 16, 2021. Retrieved August 16, 2021.

- ^ Kaplan, Allison (November 22, 2020). "Long-time Biden aide Blinken most likely choice for secretary of state". Haaretz. Archived from the original on November 24, 2020. Retrieved November 24, 2020.

- ^ Herszenhorn, David (November 23, 2020). "Nine things to know about Antony Blinken". Politico. Archived from the original on November 24, 2020. Retrieved November 24, 2020.

- ^ Sevastopulo, Demetri (November 23, 2020). "Biden's 'alter ego' Antony Blinken tipped for top foreign policy job". Financial Times. Archived from the original on November 24, 2020. Retrieved November 23, 2020.

- ^ Shaffer, Claire (November 23, 2020). "Yes, Biden's Secretary of State Hopeful Antony Blinken Has a Band". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on November 24, 2020. Retrieved November 23, 2020.

- ^ "Music Review: Secretary of State Pick Antony Blinken". NPR.org. Archived from the original on January 25, 2021. Retrieved January 26, 2021.

외부 링크

- 미국 국무부 전기

- 미국 국무부 전기 (2009-2017, 아카이브)

- 상원 외교위원회 미국 국무장관 인사청문회(2021년 1월 19일)

- WestExec Advisors의 Wayback Machine 프로필(2021년 1월 20일 보관)

- C-SPAN에서의 모습

- 트위터의 안토니 블링컨