캐나다

Canada캐나다 | |

|---|---|

| 모토: 마리퀴드 암말 (라틴어) "바다에서 바다로" | |

| 애국가: "오 캐나다" | |

| |

| 자본의 | 오타와 45°24'N 75°40'W / 45.400°N 75.667°W |

| 가장 큰 도시 | 토론토 |

| 공용어 | |

| 성명서 | 캐나디안 |

| 정부 | 연방의 의회의 입헌 군주제 |

• 군주 | 샤를 3세 |

• 총독부 | 메리 사이먼 |

• 수상 | 쥐스탱 트뤼도 |

| 입법부 | 의회. |

• 참의원 | 상원 |

• 하원 | 하원 |

| 인디펜던스 | |

• 컨페더레이션 | 1867년 7월 1일 |

| 1931년 12월 11일 | |

• 애국 | 1982년4월17일 |

| 지역 | |

• 총면적 | 9,984,670 km2 (3,855,100 sq mi) (2nd) |

• 물(%) | 11.76 (2015)[2] |

• 총면적 | 9,093,507 km2 (3,511,023 sq mi) |

| 인구. | |

• 2023년 4분기 예상 | |

• 2021년 인구조사 | 36,991,981[4] |

• 밀도 | 4.2/km2 (10.9/sq mi) (236th) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2023년 견적 |

• 합계 | |

• 인당 | |

| GDP (nominal) | 2023년 견적 |

• 합계 | |

• 인당 | |

| 지니 (2018) | 중간의 |

| HDI (2021) | 매우 높은 · 15위 |

| 통화 | 캐나다 달러($)(CAD) |

| 시간대 | UTC−3.5 to −8 |

• 여름(DST) | UTC−2.5 to −7 |

| 호출부호 | +1 |

| 인터넷 TLD | .ca |

캐나다는 북미에 있는 나라입니다. 대서양에서 태평양, 북쪽으로 북극해까지 이어지는 10개의 지방과 3개의 영토가 뻗어 있어 전체 면적으로 세계에서 두 번째로 큰 나라이며, 해안선이 가장 긴 나라입니다. 미국과의 국경은 세계에서 가장 긴 국제 육상 국경입니다. 이 나라는 기상 지역과 지질 지역 모두에서 광범위한 것이 특징입니다. 인구 4천만 명의 인적이 드문 나라로, 대다수가 55도선 이남에 도시 지역에 거주하고 있습니다. 캐나다의 수도는 오타와이고 캐나다의 세 개의 가장 큰 대도시 지역은 토론토, 몬트리올, 밴쿠버입니다.

원주민들은 수천 년 동안 지금의 캐나다에 지속적으로 거주해 왔습니다. 16세기에 시작된 영국과 프랑스 탐험대는 대서양 연안을 탐험하고 나중에 정착했습니다. 다양한 무력 충돌의 결과로, 프랑스는 1763년에 북아메리카에 있는 거의 모든 식민지를 양도했습니다. 1867년 연합을 통해 3개의 영국령 북아메리카 식민지가 연합되면서 캐나다는 4개의 주로 구성된 연방 자치령으로 형성되었습니다. 이것은 지방과 영토의 증가와 영국으로부터의 자치를 증가시키는 과정을 시작했고, 1931년 웨스트민스터 법령에 의해 강조되었고, 1982년 영국 의회에 대한 법적 의존의 흔적을 단절시킨 캐나다 법으로 끝이 났습니다.

캐나다는 웨스트민스터 전통에서 의회 민주주의와 입헌 군주제입니다. 이 나라의 정부 수반은 선출된 하원의 신임을 지휘할 수 있는 능력 덕분에 총리직을 유지하고 국가 원수인 캐나다의 군주를 대표하는 총독에 의해 "부름"을 받습니다. 이 나라는 영연방 국가이며 연방 관할권에서 공식적으로 이중 언어(영어와 프랑스어)를 사용합니다. 정부 투명성, 삶의 질, 경제적 경쟁력, 혁신, 교육 및 양성 평등에 대한 국제적인 측정에서 매우 높은 순위에 있습니다. 대규모 이민의 산물인 세계에서 가장 인종적으로 다양하고 다문화적인 국가 중 하나입니다. 캐나다와 미국의 길고 복잡한 관계는 캐나다의 역사, 경제, 문화에 중대한 영향을 미쳤습니다.

선진국인 캐나다는 세계적으로 1인당 명목 소득이 높고 선진 경제는 풍부한 천연 자원과 잘 발달된 국제 무역 네트워크에 주로 의존하면서 세계에서 가장 큰 나라 중 하나입니다. 캐나다는 다자적 해결책을 추구하는 경향이 있는 국제 문제에 대한 역할로 중견국으로 인정받고 있습니다. 20세기 동안 캐나다의 평화 유지 역할은 캐나다의 글로벌 이미지에 큰 영향을 미쳤습니다. 캐나다는 여러 주요 국제 및 정부 간 기관의 일부입니다.

어원

다양한 이론들이 캐나다의 어원적 기원에 대해 가정되어 왔지만, 그 이름은 이제 "마을" 또는 "정착지"를 의미하는 St. Lawrence Iroquoian 단어 kanata에서 온 것으로 받아들여집니다.[8] 1535년, 오늘날 퀘벡시 지역의 토착민들은 프랑스 탐험가 자크 카르티에를 스타다코나 마을로 향하게 하기 위해 이 단어를 사용했습니다.[9] 카르티에는 나중에 캐나다라는 단어를 그 특정 마을뿐만 아니라 도나코나(스타다코나의 추장)의 대상이 되는 전체 지역을 가리키는 데 사용했습니다.[9] 1545년까지 유럽의 책과 지도는 세인트로렌스 강을 따라 있는 이 작은 지역을 캐나다라고 부르기 시작했습니다.[9]

16세기부터 18세기 초까지, "캐나다"는 세인트로렌스 강을 따라 놓여있는 뉴 프랑스의 부분을 언급했습니다.[10] 1791년, 이 지역은 어퍼 캐나다와 로어 캐나다라고 불리는 두 개의 영국 식민지가 되었습니다. 이 두 식민지는 1841년에 영국령 캐나다로 통합될 때까지 캐나다라는 이름으로 통칭되었습니다.[11]

1867년 연합에 따라, 캐나다는 런던 회의에서 새로운 국가의 법적 이름으로 채택되었고, 도미니언이라는 단어는 국가의 칭호로 수여되었습니다.[12] 1950년대에 이르러서는 캐나다를 "영연방의 영역"으로 여겼던 영국이 캐나다의 영토라는 용어를 더 이상 사용하지 않게 되었습니다.[13]

1982년 캐나다 헌법을 완전히 캐나다의 통제하에 두게 된 캐나다법은 오직 캐나다만을 지칭했습니다. 그 해 말, 국경일의 이름은 도미니언 데이에서 캐나다 데이로 바뀌었습니다.[14] 도미니언이라는 용어는 연방 정부와 지방을 구별하기 위해 사용되었지만, 제2차 세계 대전 이후에는 연방이라는 용어가 자치령을 대체했습니다.[15]

역사

원주민

북아메리카의 첫 번째 거주자들은 일반적으로 시베리아에서 베링 육교를 통해 이주하여 적어도 14,000년 전에 도착한 것으로 추정됩니다.[16][17] 올드 크로우 플랫(Old Crow Flats)과 블루피쉬 동굴(Bluefish Caves)에 있는 팔레오-인디언 고고학 유적지는 캐나다에서 가장 오래된 인간 거주지 중 두 곳입니다.[18] 원주민 사회의 특징은 영구적인 정착, 농업, 복잡한 사회 계층, 무역 네트워크를 포함했습니다.[19][20] 이 문화들 중 일부는 유럽 탐험가들이 15세기 말에서 16세기 초에 도착했을 때 붕괴되어 고고학적 조사를 통해서만 발견되었습니다.[21] 오늘날 캐나다의 원주민은 퍼스트 네이션스, 이누이트, 메티스를 포함하며,[22] 이는 17세기 중반 퍼스트 네이션스 사람들이 유럽 정착민들과 결혼하여 그들만의 정체성을 발전시킨 마지막 혼혈인입니다.[22]

최초의 유럽 정착 당시 원주민 인구는 200,000명에서[24] 200,000만 명 사이로 추정되며,[25] 그 수치는 50만 명으로 캐나다 원주민 왕립 위원회에 의해 받아들여졌습니다.[26] 유럽의 식민지화의 결과로 원주민 인구가 40~80% 감소했고 버툭족과 같은 몇몇 퍼스트 네이션은 사라졌습니다.[27] 이러한 감소는 인플루엔자, 홍역, 천연두 등 자연면역력이 없던 유럽의 질병이 옮겨온 것,[24][28] 모피 거래를 둘러싼 갈등, 식민지 당국과 정착민들과의 갈등 등 여러 원인에 기인한 것으로 판단됩니다. 정착민들에게 원주민의 땅을 빼앗기고 그에 따른 몇몇 국가들의 자급자족의 붕괴.[29][30]

분쟁이 없는 것은 아니지만, 유럽계 캐나다인들이 퍼스트 네이션과 이누이트 인구들과 초기에 교류한 것은 비교적 평화로운 것이었습니다.[31] 퍼스트 네이션스와 메티스인들은 캐나다에서 유럽 식민지를 개발하는 데 중요한 역할을 했습니다. 특히 북미 모피 무역 기간 동안 유럽인 여행객들이 유럽 대륙을 탐험하는 것을 돕는 데 그들의 역할을 했습니다.[32] 이러한 초기 유럽의 퍼스트 네이션과의 상호작용은 우호 및 평화 조약에서 조약을 통한 원주민 토지의 처분으로 바뀔 것입니다.[33][34] 18세기 후반부터 유럽계 캐나다인들은 원주민들에게 서부 캐나다 사회에 동화되도록 강요했습니다.[35] 이러한 시도는 19세기 말과 20세기 초에 국가가 지원하는 기숙학교를 통한 강제 통합,[36] 의료 분리 [37]및 이주와 함께 절정에 달했습니다.[38] 2008년 캐나다 정부에 의해 캐나다 진실화해위원회가 결성되면서 화해의 시기가 시작되었습니다.[39] 여기에는 과거 식민지의 부당함과 정착 협정을 인정하고 실종되고 살해된 원주민 여성들의 곤경을 해결하는 것과 같은 인종 차별 문제를 개선하는 것이 포함되었습니다.[39][40]

유럽의 식민지화

캐나다의 동쪽 해안을 탐험한 최초의 문서화된 유럽인은 북유럽 탐험가인 레이프 에릭슨(Leif Erikson)이라고 믿어집니다.[42][43] 서기 약 1000년에 북유럽인들은 뉴펀들랜드 북쪽 끝에 있는 L'Anseaux Meadows에 20년 동안 산발적으로 점령했던 작은 단기 캠프를 건설했습니다.[44] 1497년 선원 존 캐벗이 영국의 헨리 7세의 이름으로 캐나다의 대서양 연안을 탐험하고 영유권을 주장하기 전까지 더 이상의 유럽 탐험은 일어나지 않았습니다.[45] 1534년 프랑스 탐험가 자크 카르티에는 세인트로렌스 만을 탐험했고, 7월 24일 "프랑스 왕 만세"라는 문구가 적힌 10미터(33피트) 십자가를 심고 프랑수아 1세의 이름으로 뉴프랑스 영토를 차지했습니다.[46] 16세기 초 바스크인과 포르투갈인이 개척한 항해 기술을 가진 유럽의 항해사들이 대서양 연안을 따라 계절별 포경과 어업 전초기지를 건설했습니다.[47] 일반적으로 발견 시대 초기 정착지는 혹독한 기후, 무역로 탐색 문제, 스칸디나비아의 경쟁적인 생산량 등이 복합적으로 작용하여 수명이 짧았던 것으로 보입니다.[48][49]

1583년 엘리자베스 1세 여왕의 왕권에 의해 험프리 길버트 경은 최초의 북미 영어 계절 캠프로 뉴펀들랜드의 세인트 존스를 설립했습니다.[50] 1600년, 프랑스인들은 세인트로렌스 강을 따라 타두삭에 그들의 첫 계절 무역소를 세웠습니다.[44] 프랑스 탐험가 사뮈엘 드 샹플랭은 1603년에 도착하여 포트 로얄 (1605년)과 퀘벡 시 (1608년)에 유럽 최초의 영구적인 연중 거주지를 설립했습니다.[51] 뉴프랑스의 식민지 개척자들 사이에서, 캐나다인들은 광범위하게 세인트로렌스 강 계곡에 정착했고, 아카디아인들은 오늘날의 해양에 정착했고, 모피 상인들과 가톨릭 선교사들은 오대호, 허드슨 만, 그리고 루이지애나에 이르는 미시시피 유역을 탐험했습니다.[52] 비버 전쟁은 17세기 중반 북미 모피 무역을 통제하기 위해 일어났습니다.[53]

영국인들은 남쪽의 13개 식민지에 정착지와 함께 1610년 뉴펀들랜드에 추가적인 정착지를 세웠습니다.[54][55] 1689년에서 1763년 사이에 식민지 북아메리카에서 4개의 전쟁이 발생했습니다. 이 시기의 후기 전쟁은 7년 전쟁의 북미 극장을 구성했습니다.[56] 노바스코샤 본토는 1713년 위트레흐트 조약과 캐나다로 영국의 지배를 받게 되었고 뉴프랑스의 대부분은 7년 전쟁 이후인 1763년에 영국의 지배를 받게 되었습니다.[57]

영국령 북아메리카

1763년의 왕실 선언은 퍼스트 네이션 조약권을 확립했고, 신프랑스로부터 퀘벡주를 만들어냈고, 브르타뉴 곶을 노바스코샤에 합병했습니다.[14] 세인트 존 섬(현재 프린스에드워드 섬)은 1769년에 별도의 식민지가 되었습니다.[59] 퀘벡의 분쟁을 막기 위해 영국 의회는 1774년 퀘벡 법을 통과시켜 퀘벡의 영토를 오대호와 오하이오 계곡으로 확장했습니다.[60] 더 중요한 것은, 13개 식민지가 점점 더 영국의 통치에 반대하는 선동을 하던 시기에 퀘벡 법이 퀘벡에 특별한 자치권과 자치 행정권을 부여했다는 것입니다.[61] 그곳에서 프랑스어, 가톨릭 신앙, 프랑스 민법을 다시 제정하여 13개 식민지와 대조적인 독립 운동의 성장을 막았습니다.[62] 포고령과 퀘벡 법은 차례로 13개 식민지의 많은 주민들을 화나게 했고, 미국 독립 혁명 이전에 반영 감정을 더욱 부추겼습니다.[14]

성공적인 미국 독립 전쟁 이후, 1783년 파리 조약은 새로 형성된 미국의 독립을 인정하고 평화 조건을 설정하여 오대호 남쪽과 미시시피 강 동쪽의 영국령 북아메리카 영토를 새로운 나라로 양도했습니다.[63] 미국 독립 전쟁은 또한 미국 독립에 맞서 싸웠던 정착민인 충성파의 대규모 이주를 야기시켰습니다. 많은 사람들이 캐나다, 특히 대서양 캐나다로 이주했고, 그곳에서 그들의 도착은 기존 영토의 인구 분포를 바꿨습니다. 뉴브런즈윅은 해전에서 충성파 정착지의 재편성의 일환으로 노바스코샤에서 분리되었고, 이로 인해 뉴브런즈윅의 세인트 존이 캐나다의 첫 도시로 통합되었습니다.[64] 1791년 헌법은 중앙 캐나다에서 영어를 사용하는 충성파의 유입을 수용하기 위해 캐나다 지방을 프랑스어를 사용하는 로어 캐나다(나중에 퀘벡)와 영어를 사용하는 로어 캐나다(나중에 온타리오)로 나누어 각각의 선출된 입법부를 승인했습니다.[65]

캐나다는 미국과 영국 사이의 1812년 전쟁의 주요 전선이었습니다. 1815년에 평화가 찾아왔습니다. 경계는 변경되지 않았습니다.[67] 이민은 1815년에서 1850년 사이에 영국에서 96만 명 이상이 도착하면서 더 높은 수준으로 재개되었습니다.[68] 새로 도착한 사람들에는 아일랜드 대기근을 탈출한 난민들과 하이랜드 클리어런스에 의해 추방된 게일어를 사용하는 스코틀랜드 사람들이 포함되었습니다.[69] 1891년 이전에 캐나다로 이민 온 유럽인의 25%에서 33%가 감염병으로 사망했습니다.[24]

책임 있는 정부에 대한 열망은 1837년의 실패한 반란으로 이어졌습니다.[70] Durham Report는 이후에 책임 있는 정부와 프랑스계 캐나다인들을 영국 문화에 동화시킬 것을 권고했습니다.[14] 1840년 연합법(Act of Union 1840)은 캐나다를 캐나다 연합주로 통합하고 1855년까지 슈피리어호 동쪽의 영국령 북아메리카의 모든 주에 책임 정부가 수립되었습니다.[71] 1846년 영국과 미국이 오리건 조약을 체결하면서 오리건 국경 분쟁은 종식되었고, 국경선은 49도선을 따라 서쪽으로 확장되었습니다. 이것은 밴쿠버 섬(1849)과 브리티시 컬럼비아(1858)에 영국 식민지를 위한 길을 닦았습니다.[72] 상트페테르부르크 조약(1825년)으로 태평양 연안에 국경이 설정되었지만, 1867년 미국의 알래스카 수매 이후에도 알래스카의 정확한 경계 획정에 대한 분쟁이 계속되었습니다.유콘과 알래스카 –BC 보더.[73]

연합과 확장

1867년 제헌 회의를 거쳐 1867년 7월 1일에 공식적으로 캐나다 연방을 선포했습니다. 온타리오, 퀘벡, 노바스코샤, 뉴브런즈윅.[75][76] 캐나다는 루퍼트 땅과 북서부 영토를 장악하여 북서부 영토를 형성했으며, 메티스의 불만은 1870년 7월 홍강 반란과 매니토바 지방의 설립에 불을 붙였습니다.[77] 1871년 브리티시컬럼비아주와 밴쿠버섬(1866년 통합)은 대륙횡단철도가 10년 이내에 빅토리아주까지 연장될 것이라는 약속에 따라 연방에 가입했고,[78] 프린스에드워드아일랜드주는 1873년에 가입했습니다.[79] 1898년 북서부 지역의 클론다이크 골드러시 때 의회는 유콘 준주를 만들었습니다. 앨버타와 서스캐처원은 1905년에 주가 되었습니다.[79] 1871년에서 1896년 사이에 캐나다 인구의 거의 4분의 1이 미국으로 남쪽으로 이민을 갔습니다.[80]

서부를 개방하고 유럽의 이민을 장려하기 위해 캐나다 정부는 3개의 대륙횡단 철도(캐나다 태평양 철도 포함) 건설을 후원하고, 정착을 규제하기 위해 도미니언 토지법을 통과했으며, 북서부 기마 경찰을 설립하여 영토에 대한 권한을 주장했습니다.[81][82] 서부로의 확장과 국가 건설의 이 시기는 캐나다 대초원의 많은 원주민들을 "인도 보호구역"으로 이주시키는 결과를 가져왔고,[83] 유럽 민족의 블록 정착을 위한 길을 열었습니다.[84] 이로 인해 캐나다 서부의 들소 평원이 붕괴되고 유럽의 소 농장과 밀밭이 이 땅을 지배하게 되었습니다.[85] 원주민들은 들소와 그들의 전통적인 사냥터의 상실로 인해 광범위한 기근과 질병을 겪었습니다.[86] 연방 정부는 원주민이 보호구역으로 이동하는 것을 조건으로 긴급 구호를 제공했습니다.[87] 이 시기에 캐나다는 교육, 정부 및 법적 권리에 대한 인도법을 도입했습니다.[88]

20세기 초

1867년 영국령 북아메리카법에 따라 영국이 여전히 캐나다의 외교를 통제하고 있었기 때문에, 1914년의 선전포고는 자동적으로 캐나다를 제1차 세계대전으로 이끌었습니다.[89] 서부 전선에 파견된 자원봉사자들은 나중에 비미 능선 전투와 전쟁의 다른 중요한 교전에서 중요한 역할을 한 캐나다 군단의 일원이 되었습니다.[90] 제1차 세계대전에 참전한 약 62만 5천 명의 캐나다인 중 약 6만 명이 사망하고 17만 2천 명이 부상을 입었습니다.[91] 1917년 징병 위기는 프랑스어를 사용하는 퀘벡 사람들의 격렬한 반대에 부딪혀 점점 줄어드는 군대의 현역 의원 수를 징병제로 늘리자는 연합 내각의 제안이 이루어지면서 발생했습니다.[92] 병역법은 의무적인 병역을 도입했지만, 퀘벡 밖의 프랑스어 학교에 대한 분쟁과 함께 프랑스어 사용자인 캐나다인들을 깊이 소외시키고 자유당을 일시적으로 분열시켰습니다.[92] 1919년 캐나다는 영국으로부터 독립하여 국제연맹에 가입하였고,[90] 1931년 웨스트민스터 법령은 캐나다의 독립을 확인했습니다.[93]

1930년대 초 캐나다의 대공황은 경제 침체를 겪었고, 전국적으로 어려움을 겪었습니다.[94] 경기 침체에 대응하여, 서스캐처원에 있는 협동 영연방 연합(CCF)은 1940년대와 1950년대에 복지 국가의 많은 요소들을 도입했습니다.[95] 윌리엄 리옹 매켄지 킹 총리의 조언에 따라 1939년 9월 10일 조지 6세는 영국보다 7일 늦게 독일과의 전쟁을 선포했습니다. 그 지연은 캐나다의 독립을 강조했습니다.[90]

최초의 캐나다 육군 부대는 1939년 12월에 영국에 도착했습니다. 전체적으로 100만 명이 넘는 캐나다인들이 2차 세계대전 동안 군대에 복무했고 약 42,000명이 사망했고 다른 55,000명이 부상을 입었습니다.[96] 캐나다군은 1942년 실패한 디에프 공습, 연합군의 이탈리아 침공, 노르망디 상륙작전, 노르망디 해전, 1944년 셸트 해전 등 전쟁의 많은 중요한 전투에서 중요한 역할을 했습니다.[90] 캐나다는 네덜란드가 점령된 동안 네덜란드 왕정에 망명을 제공했으며 네덜란드가 나치 독일로부터 해방하는 데 큰 기여를 한 것으로 인정받고 있습니다.[97]

캐나다 경제는 캐나다, 영국, 중국 및 소련의 산업이 군사 재료를 제조함에 따라 전쟁 중에 호황을 누렸습니다.[90] 1944년 퀘벡의 또 다른 징병 위기에도 불구하고 캐나다는 대규모 군대와 강력한 경제로 전쟁을 마무리했습니다.[98]

동시대

대공황의 재정 위기로 1934년 뉴펀들랜드 자치령은 책임 있는 정부를 포기하고 영국 총독이 통치하는 크라운 식민지가 되었습니다.[99] 두 번의 국민투표 후, 뉴펀들랜더들은 1949년 캐나다에 속주로 가입하기로 투표했습니다.[100]

캐나다의 전후 경제 성장은 연속적인 자유당 정부의 정책과 결합하여 1965년 단풍잎 깃발의 채택,[101] 1969년 공식 이중언어(영어와 프랑스어)의 시행,[102] 1971년 공식 다문화주의의 도입으로 특징지어지는 새로운 캐나다 정체성의 출현으로 이어졌습니다.[103] 메디케어, 캐나다 연금 계획, 캐나다 학자금 대출과 같은 사회 민주적 프로그램도 도입되었지만 지방 정부, 특히 퀘벡과 앨버타는 이러한 프로그램 중 많은 부분을 관할권에 대한 침해로 반대했습니다.[104]

마지막으로, 또 다른 일련의 제헌 회의들은 캐나다의 권리와 자유 헌장의 제정과 동시에 1982년 캐나다 헌법을 영국으로부터 애국하는 캐나다 법이라는 결과를 낳았습니다.[106][107][108] 캐나다는 독자적인 군주제 하에서 독립 국가로서 완전한 주권을 확립했습니다.[109][110] 1999년, 누나부트는 연방 정부와 일련의 협상 끝에 캐나다의 세 번째 영토가 되었습니다.[111]

동시에 퀘벡은 1960년대의 조용한 혁명을 통해 심각한 사회적, 경제적 변화를 겪었고 세속적인 민족주의 운동을 낳았습니다.[112] 급진적인 민주전선(FLQ)은 1970년 일련의 폭탄 테러와 납치로 10월 위기에 불을 붙였고,[113] 1976년 주권자인 파르티 케베코이스가 선출되어 1980년 주권-연합에 대한 실패한 국민투표를 조직했습니다. 1990년 미크레이크 협정을 통해 퀘벡 민족주의를 헌법적으로 수용하려는 시도는 실패했습니다.[114] 이로 인해 퀘벡에서는 퀘벡 블록이 형성되었고, 서부에서는 캐나다 개혁당이 활성화되었습니다.[115][116] 1995년 제2차 국민투표가 실시되어 50.6~49.4%의 근소한 차이로 주권이 부결되었습니다.[117] 1997년 대법원은 지방에 의한 일방적인 분리가 위헌이라고 판결했고, 의회는 협상된 연방 탈퇴 조건을 명시하는 명확성법을 통과시켰습니다.[114]

퀘벡 주권 문제 외에도 1980년대 후반과 1990년대 초반 캐나다 사회는 여러 차례 위기를 겪었습니다. 여기에는 1985년 캐나다 역사상 가장 큰 규모의 대규모 살인 사건인 에어 인디아 182편의 폭발,[118] 1989년 에콜 폴리테크니크 대학살, 여학생들을 겨냥한 대학 총기 난사,[119] 1990년 오카 사태 등이 포함되었습니다.[120][121] 캐나다도 1990년 미국이 주도하는 연합군의 일부로 걸프전에 참전했으며 1990년대 구 유고슬라비아의 유엔프로포 임무를 포함한 여러 평화유지 임무에서 활동했습니다.[122] 캐나다는 2001년 아프가니스탄에 군대를 파견했지만 2003년 미국이 주도하는 이라크 침공에 동참하지 않았습니다.[123]

2011년 캐나다군은 나토 주도의 리비아 내전[124] 개입에 참여했고, 2010년대 중반 이라크 내 이슬람국가(IS) 반군과의 전투에도 참여했습니다.[125] 이 나라는 2020년 1월 27일 캐나다의 COVID-19 팬데믹이 시작되기 3년 전인 2017년에 광범위한 사회 및 경제적 혼란과 함께 10주년을 기념했습니다.[126] 2021년에는 캐나다 인디언 거주 학교의 이전 부지 근처에서 수백 명의 원주민 무덤이 발견되었습니다.[127] 1828년부터 1997년까지 다양한 기독교 교회가 관리하고 캐나다 정부가 자금을 지원한 이 기숙학교들은 원주민 아이들을 유럽계 캐나다 문화에 동화시키려고 시도했습니다.[36]

지리

총 면적(수역 포함)에서 캐나다는 러시아 다음으로 세계에서 두 번째로 큰 나라입니다.[128] 캐나다는 세계에서 가장 넓은 담수호 면적을 가지고 있기 때문에 육지 면적으로만 보면 4위를 차지하고 있습니다.[129] 동쪽의 대서양에서 북쪽의 북극해를 따라, 그리고 서쪽의 태평양까지 뻗어 있는 이 나라는 9,984,670 km2 (3,855,100 sq mi)의 영토를 포함하고 있습니다.[130] 캐나다는 또한 세계에서 가장 긴 해안선의 길이가 243,042 킬로미터(151,019 마일)인 광대한 해양 지형을 가지고 있습니다.[131][132] 미국과 세계에서 가장 큰 국경을 공유하는 것 외에도 8,891 km(5,525 mi)[a]에 걸쳐 있습니다.—캐나다는 북동쪽으로 그린란드(따라서 덴마크 왕국)와 국경을 접하고 있으며,[133] 남동쪽으로 프랑스의 생 피에르와 미켈론의 해외 집합체와 해상 경계를 공유하고 있습니다.[134] 캐나다는 또한 엘즈미어 섬의 북단에 위치한 세계 최북단에 위치한 캐나다군 기지 경보의 본거지입니다. 위도 82.5°N—북극에서 817 킬로미터(508 마일) 떨어져 있습니다.[135]

캐나다는 7개의 물리학적 지역으로 나뉩니다: 캐나다 방패, 내부 평원, 오대호-성. 로렌스 로우랜즈, 애팔래치아 지역, 웨스턴 코딜레라, 허드슨 베이 로우랜즈, 북극 군도.[136] 북방림은 전국에 널리 퍼져 있고, 북극 북부 지역과 로키 산맥을 통해 얼음이 두드러지며, 남서쪽의 비교적 평평한 캐나다 대초원은 생산적인 농업을 용이하게 합니다.[130] 오대호는 캐나다 경제 생산의 대부분을 저지대가 차지하는 세인트로렌스 강(동남쪽)에 공급합니다.[130] 캐나다는 2,000,000개가 넘는 호수를 가지고 있는데, 그 중 563개는 100km2(39sq mi) 이상의 큰 호수로 세계 담수의 많은 부분을 포함하고 있습니다.[137][138] 캐나다 로키스 산맥, 해안 산맥, 북극 코르디예라에도 담수 빙하가 있습니다.[139] 캐나다는 지질학적으로 활동적이며 많은 지진과 잠재적인 활화산, 특히 미거마시프산, 가리발디산, 케일리산, 에지자산 화산 단지가 있습니다.[140]

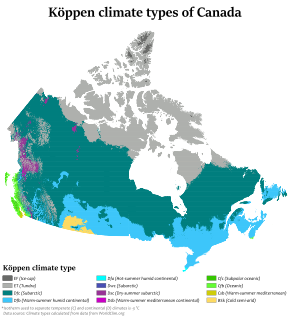

기후.

캐나다 전역의 겨울과 여름 평균 최고 기온은 지역마다 다릅니다. 겨울은 특히 대륙성 기후를 경험하는 내륙 지방과 프레리 지방에서 가혹할 수 있으며, 이 지역은 일평균 기온이 -15°C(5°F)에 가깝지만 심한 바람이 부는 등 -40°C(-40°F) 이하로 떨어질 수 있습니다.[141] 비해안 지역에서는 1년 중 거의 6개월 동안 눈이 땅을 덮을 수 있는 반면, 북쪽의 일부 지역에서는 1년 내내 눈이 지속될 수 있습니다. 브리티시컬럼비아주 해안은 온화한 기후를 가지고 있으며, 겨울은 온화하고 비가 많이 옵니다. 동해안과 서해안의 평균 최고 기온은 대체로 20도(70도) 낮은 반면, 해안 사이의 평균 여름 최고 기온은 25~30도(77~86도)이며, 일부 내륙 지역의 기온은 40도(104도)를 초과하기도 합니다.[142]

캐나다 북부의 많은 지역이 얼음과 영구 동토층으로 덮여있습니다. 캐나다의 기후 변화로 북극이 지구 평균의 3배에 달하는 온난화를 겪고 있기 때문에 영구 동토층의 미래는 불확실합니다.[143] 캐나다의 육지 연평균 기온은 1948년 이래로 1.7 °C (3.1 °F) 상승했고, 다양한 지역에서 1.1 ~ 2.3 °C (2.0 ~ 4.1 °F)의 변화가 있었습니다.[130] 온난화 속도는 북부와 대초원에서 더 높았습니다.[144] 캐나다 남부 지역에서는 금속 제련, 전력회사에 석탄 연소, 차량 배출로 인한 캐나다와 미국의 대기 오염으로 산성비가 발생하여 수로, 산림 성장, 캐나다의 농업 생산성에 심각한 영향을 미쳤습니다.[145]

생물다양성

캐나다는 15개의 육상 에코존과 5개의 해양 에코존으로 나뉩니다.[147] 이 에코존들은 8만 종 이상의 분류된 캐나다 야생동물을 포함하고 있으며, 아직 공식적으로 인정되거나 발견되지 않은 것과 같은 숫자입니다.[148] 캐나다는 다른 나라에 비해 고유종의 비율이 낮지만,[149] 인간의 활동, 침입종, 환경 문제로 인해 현재 800종 이상이 유실될 위험에 처해 있습니다.[150] 캐나다에 서식하는 종의 약 65 퍼센트가 "안전한" 종으로 여겨집니다.[151] 캐나다의 풍경의 절반 이상은 온전하고 인간의 개발이 상대적으로 자유롭습니다.[152] 캐나다의 북방림은 약 3,000,000 km2(1,200,000 sq mi)가 도로, 도시 또는 산업에 의해 방해받지 않고 지구에서 가장 큰 온전한 숲으로 간주됩니다.[153] 지난 빙하기가 끝난 이후, 캐나다는 8개의 다른 숲 지역으로 구성되어 있으며,[154] 땅 면적의 42%가 숲으로 덮여 있습니다 (세계 숲이 우거진 땅의 약 8%).[155]

보호 구역으로 지정된 11.4%를 포함하여, 우리나라 국토 면적과 담수의 약 12.1%가 보존 구역입니다.[156] 보호 구역으로 지정된 8.9%를 포함하여 약 13.8%의 영해가 보존되어 있습니다.[156] 1885년에 설립된 캐나다 최초의 국립공원인 밴프 국립공원은 6,641㎢([157]2,564㎢)의 산악지형에 걸쳐 있으며, 많은 빙하와 빙원, 울창한 침엽수림, 고산 경관을 갖추고 있습니다.[158] 1893년에 설립된 캐나다에서 가장 오래된 도립공원인 알곤킨 도립공원의 면적은 7,653.45 평방 킬로미터(2,955.01 평방 마일)입니다. 이곳은 2,400개 이상의 호수와 1,200km의 개울과 강이 있는 오래된 숲이 지배적입니다.[159] 슈페리어 호수 국립 해양 보호 구역은 약 10,000 평방 킬로미터(3,900 평방 마일)의 호수 바닥, 겹쳐진 담수 및 60 평방 킬로미터(23 평방 마일)의 섬과 본토에 걸쳐 있는 세계에서 가장 큰 담수 보호 구역입니다.[160] 캐나다에서 가장 큰 국립 야생동물 지역은 스콧 제도 해양 국립 야생동물 지역으로, 11,570.65 평방 킬로미터 (4,467.45 평방 마일)[161]에 걸쳐 있으며 브리티시 컬럼비아의 바닷새 40 퍼센트 이상의 중요한 번식과 둥지 서식지를 보호하고 있습니다.[162] 캐나다의 18개 유네스코 생물권 보호구역은 총 235,000 평방 킬로미터(91,000 평방 마일)의 면적을 차지하고 있습니다.[163]

정부와 정치

캐나다는 자유주의 전통과 [165]평등주의적이고 [166]온건한 정치 이념을 가진 [164]"완전한 민주주의"로 묘사됩니다.[167] 사회 정의에 대한 강조는 캐나다 정치 문화의 두드러진 요소였습니다.[168][169] 평화, 질서, 좋은 정부는 내재된 권리장전과 함께 캐나다 정부의 설립 원칙입니다.[170][171]

연방 차원에서 캐나다는 중도좌파 성향의 캐나다[178][179] 자유당과 중도우파 성향의 캐나다 보수당(또는 그 이전 정당)이라는 비교적 중도 성향의 두 정당이 지배해 왔습니다.[b][180] 역사적으로 우세한 자유당은 정치적 규모의 중심에 위치하고 있습니다.[180] 2021년 선거에서 소수 정부를 구성한 자유당, 공식 야당이 된 보수당, 신민주당(좌파[181][182] 점령), 퀘벡 블록(Block Quebecois), 캐나다 녹색당 등 5개 정당이 의회에 선출되었습니다.[183] 극우와 극좌 정치는 캐나다 사회에서 두드러진 세력이 된 적이 없습니다.[184][185][186]

캐나다는 입헌 군주제의 맥락에서 의회 제도를 가지고 있습니다. 즉, 캐나다의 군주제는 행정부, 입법부, 사법부의 기반입니다.[187][188][189][190] 군림하는 군주는 또한 14개의 다른 영연방 국가들과 캐나다의[191] 10개의 주들의 군주입니다. 캐나다에서 대부분의 연방 왕실 업무를 수행하기 위해 군주는 총리의 조언에 따라 대표자인 총독을 임명합니다.[192][193]

군주제는 캐나다에서 주권과 권위의 원천입니다.[190][194][195] 그러나 총독이나 군주가 특정한 드문 위기 상황에서 장관의 조언 없이 권력을 행사할 수 있는 반면,[194] 집행권원(또는 왕권)의 사용은 항상 내각에 의해 지시되고, 선출된 하원에 책임이 있고 정부 수반인 [196]수상이 선출하고 위원장을 맡는 내각의 장관들로 구성된 위원회. 정부의 안정성을 보장하기 위해 통상적으로 주지사는 하원 의원 과반수의 신임을 얻을 수 있는 정당의 현재 지도자인 사람을 총리로 임명합니다.[197] 따라서 국무총리실(PMO)은 앞서 언급한 것 외에도 주지사, 부지사, 상원의원, 연방법원 판사 등 대부분의 의회 승인을 위한 입법을 시작하고, 국무총리가 임명하도록 선택하는 가장 강력한 정부 기관 중 하나입니다. 그리고 크라운 기업과 정부 기관의 수장들입니다.[194] 두 번째로 많은 의석을 가진 당의 지도자는 보통 공식 야당의 지도자가 되며 정부를 견제하기 위한 적대적인 의회 제도의 일부입니다.[198]

캐나다 의회는 연방 영역 내의 모든 법령을 통과시킵니다. 군주, 하원, 상원으로 구성됩니다. 캐나다는 영국의 의회 지상주의 개념을 계승했지만, 이는 1982년 헌법법 제정과 함께 나중에 미국의 법 지상주의 개념으로 거의 완전히 대체되었습니다.[200]

하원의 338명의 의원들은 각각 선거구에서 단순 다수결 또는 라이딩으로 선출됩니다. 1982년 헌법법은 선거 사이에 5년을 초과해서는 안 된다고 규정하고 있는데, 비록 캐나다 선거법이 10월에 "고정된" 선거일로 이것을 4년으로 제한하지만; 총선은 여전히 주지사에 의해 소집되어야 하고 총리의 조언이나 하원에서의 잃어버린 신임 투표에 의해 촉발될 수 있습니다.[201][202] 지역별로 의석이 배분되는 상원의원 105명은 75세까지 근무합니다.[203]

캐나다 연방주의는 정부 책임을 연방 정부와 10개 지방으로 나눕니다. 주 의회는 단원제이며 하원과 유사한 의회 방식으로 운영됩니다.[195] 캐나다의 3개 영토에도 입법부가 있습니다. 그러나, 이들은 주권이 아니며 지방보다 헌법상 책임이 적습니다.[204] 영토 입법부도 지방 입법부와 구조적으로 다릅니다.[205]

캐나다 은행은 캐나다의 중앙 은행입니다.[206] 재무장관과 혁신과학산업부 장관은 캐나다 통계청을 재정계획 및 경제정책 개발에 활용합니다.[207] 캐나다 은행은 캐나다 은행권의 형태로 통화를 발행할 수 있는 권한을 가진 유일한 기관입니다.[208] 이 은행은 캐나다 동전을 발행하지 않습니다; 그것들은 캐나다 왕립 조폐국에 의해 발행됩니다.[209]

법

캐나다 헌법은 국가의 최고법이며 성문법과 불문법으로 구성되어 있습니다.[210] 1867년 헌법법(영국령 북미법, 1982년 이전 1867년)은 의회 선례에 근거한 통치와 연방 정부와 지방 정부 간의 분열된 권한을 확인했습니다.[211] 1931년 웨스트민스터 법령은 완전한 자치권을 부여했고 1982년 헌법법은 영국과의 모든 입법 관계를 종료시켰을 뿐만 아니라 헌법 개정 공식과 캐나다 권리 및 자유 헌장을 추가했습니다.[212] 헌장은 일반적으로 어떤 정부도 지나칠 수 없는 기본권과 자유를 보장합니다. 그러나 의회와 주 의회는 5년의 기간 동안 헌장의 특정 부분을 무시할 수 있습니다.[213]

캐나다의 사법부는 법률을 해석하는 데 중요한 역할을 하며 헌법을 위반하는 의회의 행위를 격퇴할 수 있는 권한을 가지고 있습니다. 캐나다 대법원은 최고 법원이자 최종 중재자이며 2017년 12월 18일부터 캐나다 대법원장인 Richard Wagner가 주도하고 있습니다.[214] 총독은 국무총리와 법무부 장관의 자문을 받아 법원의 9인을 임명합니다.[215] 연방 내각은 또한 주 및 영토 관할의 상급 법원에 판사를 임명합니다.[216]

관습법은 민법이 우세한 퀘벡을 제외하고는 모든 곳에서 우세합니다.[217] 형법은 전적으로 연방 책임이며 캐나다 전역에서 획일적입니다.[218] 형사 법원을 포함한 법 집행은 공식적으로 도와 시 경찰이 수행하는 도의 책임입니다.[219] 대부분의 시골 지역과 일부 도시 지역에서는 치안 책임이 연방 캐나다 왕립 기마 경찰과 계약되어 있습니다.[220]

캐나다 원주민 법은 캐나다의 원주민 집단을 위한 토지 및 전통적인 관행에 대해 헌법적으로 인정된 특정 권리를 제공합니다.[221] 유럽인들과 많은 원주민들 사이의 관계를 중재하기 위해 다양한 조약과 판례법이 제정되었습니다.[222] 가장 주목할 만한 것은, 1871년에서 1921년 사이에 원주민과 캐나다의 지배 군주 사이에 일련의 11개 조약, 즉 번호가 매겨진 조약이 체결되었다는 것입니다.[223] 이 조약들은 협의하고 수용할 의무가 있는 캐나다 크라운-인-이사회 간의 협정들입니다.[224] 1982년 헌법 제35조에 의해 원주민법의 역할과 그들이 지지하는 권리가 재확인되었습니다.[222] 이러한 권리에는 인도 건강 이전 정책을 통한 의료와 같은 서비스 제공 및 세금 면제가 포함될 수 있습니다.[225]

대외관계 및 군사

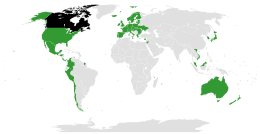

캐나다는 다자적 해결을 추구하는 성향으로 국제 문제에서 중견국으로 인정받고 있습니다.[227][228] 국제 평화 유지와 안보에 기반을 둔 캐나다의 대외 정책은 연합, 국제 기구, 그리고 다양한 연방 기관의 업무를 통해 수행됩니다.[229][230] 20세기 동안 캐나다의 평화 유지 역할은 세계적인 이미지에 큰 역할을 했습니다.[231][232] 캐나다 정부의 대외 원조 정책 전략은 지속 가능한 개발 목표를 달성하는 동시에 외국의 인도주의적 위기에 대응하는 지원을 제공한다는 강조를 반영합니다.[233] 캐나다 안보정보국(CSIS)은 테러, 스파이, 외국의 간섭 등 위협을 막기 위해 정보를 수집하고 분석하는 임무를 맡고 있으며,[234] 통신보안국(CSE)은 사이버 보안과 캐나다의 디지털 인프라 보호에 중점을 두고 있습니다.[234] 캐나다는 약 180개국 270여 곳에 외교 및 영사 사무소를 두고 있습니다.[226]

캐나다와 미국은 오랜 기간 동안 복잡하고 얽히고 설킨 관계를 맺고 있습니다.[235][236] 그들은 가까운 동맹국이며, 군사 캠페인과 인도주의적 노력에 대해 정기적으로 협력하고 있습니다.[237][238] 캐나다는 또한 국제 연합과 국제 라 프랑소니 기구에 가입함으로써 양국의 이전 식민지와 [239]함께 영국 및 프랑스와 역사적이고 전통적인 유대 관계를 유지하고 있습니다.[240] 캐나다는 네덜란드와 긍정적인 관계를 맺고 있는 것으로 유명한데, 이는 부분적으로 제2차 세계 대전 동안 네덜란드 해방에 기여했기 때문입니다.[97]

냉전 기간 동안 캐나다는 유엔군의 주요 기여자였으며 소련의 잠재적인 공중 공격을 방어하기 위해 미국과 협력하여 북미 항공 우주 방위 사령부 (NORAD)를 설립했습니다.[241] 1956년 수에즈 위기는 미래의 수상 레스터 B를 보았습니다. 피어슨은 1957년 노벨 평화상을 수상한 유엔 평화유지군의 창설을 제안함으로써 긴장을 완화했습니다.[242] 이것이 첫 유엔 평화유지 임무였기 때문에, Pearson은 종종 이 개념의 발명가로 인정받고 있습니다.[243] 캐나다는 1989년까지 모든 유엔 평화유지 활동을 포함하여 50개 이상의 평화유지 임무를 수행했습니다.[90] 125,000명 이상의 캐나다인이 유엔 평화 작전에서 복무했으며 130명의 캐나다인이 이 작전 동안 목숨을 바쳤습니다.[244] 캐나다는 특히 1993년 소말리아 사건에서 일부 외국에 연루되어 논란에 직면했습니다.[245]

통일 캐나다군(CF)은 캐나다 왕립 해군, 캐나다 육군, 캐나다 왕립 공군으로 구성됩니다. 이 나라는 약 68,000명의 현역 군인과 27,000명의 예비군으로 구성된 전문적인 자원 봉사자를 고용하고 있으며, "강력, 안전, 교전"[247] 하에 각각 71,500명과 30,000명으로 증가하고 있으며, 하위 구성 요소는 약 5,000명의 캐나다 레인저입니다.[248][c] 2021년 캐나다의 총 군사비는 약 264억 달러, 즉 캐나다 국내총생산(GDP)의 약 1.3%에 달했습니다.[250] 캐나다의 총 군사비는 2027년까지 327억 달러에 이를 것으로 예상됩니다.[251] 캐나다 군은 현재 키프로스의 스노구스 작전, 우크라이나를 지원하는 통일 작전, 카리브해의 카리브해 작전, ISIL에 대한 군사 개입 연합인 임팩트 작전 등 다양한 작전에 3000명 이상의 인력을 해외에 배치하고 있습니다.[252]

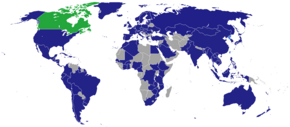

캐나다는 유엔의 창립 회원국이었고 세계 무역 기구, G20 및 경제 협력 개발 기구 (OECD)에 가입되어 있습니다.[227] 캐나다는 또한 다양한 국제 및 지역 기구와 경제 및 문화 관련 포럼의 회원국입니다.[253] 캐나다는 1976년 시민적, 정치적 권리에 관한 국제규약에 가입했습니다.[254] 이 나라는 1990년 미주기구(OAS)에 가입했고 2000년 OAS 총회와 2001년 제3차 미주정상회의를 개최했습니다.[255] 캐나다는 아시아태평양경제협력체(APEC) 회원국 가입을 통해 환태평양 경제권으로의 관계 확대를 모색하고 있습니다.[256]

주와 준주

캐나다는 지방이라고 불리는 10개의 연방 주와 3개의 연방 영토로 구성된 연방입니다. 다음은 4개의 주요 영역으로 분류할 수 있습니다. 서부 캐나다, 중부 캐나다, 대서양 캐나다, 북부 캐나다(동부 캐나다는 중부 캐나다와 대서양 캐나다를 함께 지칭함).[258] 지방과 영토는 의료, 교육 및 복지와 같은 사회 프로그램과 [259]사법 행정에 대한 책임이 있습니다(형사법은 아닙니다). 주정부는 연방 정부보다 더 많은 수입을 거둬들이고, 전 세계 다른 연방 국가들 중에서는 드문 일입니다. 연방 정부는 지출 권한을 사용하여 보건 및 보육과 같은 지방에서 국가 정책을 시작할 수 있습니다. 지방은 이러한 비용 분담 프로그램에서 제외할 수 있지만 실제로는 그렇게 하는 경우가 거의 없습니다. 연방정부는 부유한 지방과 가난한 지방 사이에 합리적으로 통일된 서비스 기준과 세금을 유지하기 위해 균등화 지급을 합니다.[260]

캐나다의 한 지방과 영토의 주요한 차이점은 지방은 왕으로부터[261] 주권을 받고 1867년 헌법법으로부터 권한과 권한을 받는 반면, 영토 정부는 캐나다[262] 의회로부터 위임된 권한을 가지고 있고 위원들은 그의 연방 의회에서 왕을 대표합니다.[263] 직접적인 군주보다는 1867년 헌법법에서 흘러나오는 권한은 연방 정부와 지방 정부가 독점적으로[264] 행사할 수 있도록 나뉘며, 그 협정에 대한 변경은 헌법 개정이 필요하며, 영토의 역할과 권한에 대한 변경은 캐나다 의회가 일방적으로 수행할 수 있습니다.[265]

경제.

캐나다는 2023년[update] 기준으로 세계 9위의 경제 대국으로,[267][268] 명목 GDP가 약 2조 2,210억 달러에 달하는 고도로 발달한 혼합 시장 경제를 보유하고 있습니다.[269] 세계에서 가장 큰 무역 국가 중 하나이며, 매우 세계화된 경제를 가지고 있습니다.[270] 2021년 캐나다의 상품 및 서비스 무역액은 2조 016억 달러에 달했습니다.[271] 캐나다의 수출액은 총 6,370억 달러가 넘었고, 수입품은 6,310억 달러가 넘었으며, 이 중 약 3,910억 달러가 미국에서 수입되었습니다.[271] 2018년 캐나다는 220억 달러의 상품 무역 적자와 250억 달러의 서비스 무역 적자를 기록했습니다.[271] 토론토 증권거래소는 시가총액 기준으로 세계에서 9번째로 큰 증권거래소로, 시가총액이 2조 달러가 넘는 1,500개가 넘는 기업들이 상장되어 있습니다.[272]

캐나다는 신용조합의 1인당 회원 수가 세계에서 가장 많은 등 강력한 협력 은행 부문을 보유하고 있습니다.[273] 부패 인식 지수(2023년 14위)[274]에서 낮은 순위를 차지하며 "세계에서 가장 부패가 적은 국가 중 하나로 널리 간주됩니다."[275] 글로벌 경쟁력 보고서(2019년 14위)[276]와 글로벌 혁신지수(2023년 15위)에서 높은 순위를 기록하고 있습니다.[277] 캐나다의 경제는 헤리티지 재단의 경제적 자유[278] 지수에서 대부분의 서구 국가들보다 높은 순위에 있으며, 상대적으로 낮은 수준의 소득 격차를 경험하고 있습니다.[279] 이 나라의 1인당 평균 가계 가처분 소득은 OECD 평균을 "훨씬 상회"하고 있습니다.[280] 캐나다는 주택 가격과[281][282] 외국인 직접 투자가 가장 발달한 국가 중 최하위권에 속합니다.[283][282]

20세기 초부터 캐나다의 제조업, 광업, 서비스업의 성장은 캐나다를 대체로 농촌 경제에서 도시화된 산업 경제로 변화시켰습니다.[284] 다른 많은 선진국들과 마찬가지로 캐나다 경제도 캐나다 노동력의 약 4분의 3을 고용하는 서비스 산업이 지배하고 있습니다.[285] 선진국 중에서도 캐나다는 특이하게 중요한 1차 부문을 가지고 있는데, 그 중에서도 임업과 석유 산업이 가장 중요한 구성 요소입니다.[286] 농업이 어려운 캐나다 북부의 많은 마을들은 인근 광산이나 목재 공급원에 의해 유지되고 있습니다.[287]

캐나다는 제2차 세계대전 이후 미국과의 경제적 통합이 크게 증가했습니다.[289] 1965년 자동차 제품 무역 협정은 자동차 제조 산업에서 무역을 위해 캐나다의 국경을 개방했습니다.[290] 1988년 캐나다-미국 자유무역협정(FTA)은 양국 간의 관세를 없앴고, 북미 자유무역협정(NAFTA)은 1994년 멕시코를 포함하도록 자유무역지대를 확대했습니다(이후 캐나다로 대체됨).미국-멕시코 협정).[291] 2023년 현재 캐나다는 51개국과 15개의 자유무역협정을 체결하고 있습니다.[288]

캐나다는 에너지 순수출국인 몇 안 되는 선진국 중 하나입니다.[286][292] 캐나다 대서양은 광대한 천연가스의 해양 매장량을 보유하고 있으며,[293] 알버타는 세계에서 네 번째로 큰 석유 매장량을 보유하고 있습니다.[294] 광대한 아타바스카 오일샌드와 다른 석유 매장량은 캐나다에 세계 석유 매장량의 13%를 제공하며, 이는 세계 3위 또는 4위를 차지합니다.[295] 캐나다는 또한 세계에서 가장 큰 농산물 공급국 중 하나입니다. 캐나다 대초원 지역은 밀, 카놀라 및 기타 곡물의 가장 중요한 전 세계 생산국 중 하나입니다.[296] 이 나라는 아연, 우라늄, 금, 니켈, 플라티노이드, 알루미늄, 철강, 철광석, 코크스 석탄, 납, 구리, 몰리브덴, 코발트 및 카드뮴의 주요 수출국입니다.[297][298] 캐나다는 온타리오주 남부와 퀘벡주를 중심으로 한 상당한 규모의 제조업 부문을 가지고 있으며, 자동차와 항공이 특히 중요한 산업을 대표합니다.[299] 어업은 또한 경제의 핵심 기여자입니다.[300]

과학기술

2020년 캐나다는 국내 연구 개발에 약 419억 달러를 지출했으며, 2022년 추가 추정치는 432억 달러입니다.[301] 2023년[update] 현재, 그 나라는 물리학, 화학, 그리고 의학 분야에서 15명의 노벨상 수상자를 배출했습니다.[302] 네이처 인덱스에 따르면, 이 나라는 과학 저널에 게재된 기사의 세계 점유율에서 7위를 차지하고 있으며,[303] 다수의 글로벌 기술 회사의 본사가 있는 곳입니다.[304] 캐나다는 세계에서 가장 높은 수준의 인터넷 접속을 가진 나라 중 하나로, 총 인구의 약 94%에 해당하는 3,300만 명 이상의 사용자가 있습니다.[305]

캐나다의 과학기술 발전에는 현대 알칼리 전지의 개발,[307] 인슐린의 발견,[308] 소아마비 백신의 개발,[309] 원자핵의 내부 구조에 대한 발견 등이 있습니다.[310] 다른 캐나다의 주요 과학적 공헌으로는 인공 심장 박동기, 시각 피질 지도 제작,[311][312] 전자 현미경,[313][314] 판 구조학, 딥 러닝, 멀티 터치 기술, 최초의 블랙홀인 시그너스 X-1의 규명 등이 있습니다.[315] 캐나다는 줄기세포, 부위 지정 돌연변이 유발, T세포 수용체, 판코니 빈혈, 낭포성 섬유증, 조기 발병 알츠하이머병을 유발하는 유전자 규명 등 유전학 분야에서 오랜 역사를 가지고 있습니다.[312][316]

캐나다 우주국은 심우주, 행성, 항공 연구를 수행하고 로켓과 위성을 개발하는 매우 활동적인 우주 프로그램을 운영하고 있습니다.[317] 캐나다는 1962년 알루엣 1호 발사로 소련과 미국에 이어 세 번째로 위성을 설계하고 제작한 나라입니다.[318] 캐나다는 국제 우주 정거장(ISS)의 참가자이며, 우주 로봇 공학의 선구자이며, ISS와 NASA의 우주 왕복선을 위해 Canadarm, Canadarm2, Canadarm3 및 Dextre 로봇 조작기를 제작했습니다.[319] 1960년대 이래로, 캐나다의 항공 우주 산업은 Radarsat-1과 2, ISIS, 그리고 MOST를 포함하여, 수많은 위성 마크를 설계하고 만들어 왔습니다.[320] 캐나다는 또한 세계에서 가장 성공적이고 널리 사용되는 소리 로켓들 중 하나인 Black Brant를 생산해 왔습니다.[321]

인구통계

2021년 캐나다 인구 조사에 따르면 총 인구는 36,991,981명으로 2016년보다 약 5.2% 증가했습니다.[323] 캐나다의 인구는 2023년에 40,000,000명을 돌파한 것으로 추정됩니다.[324] 인구 증가의 주요 동인은 이민과 더 적은 범위에서 자연적인 성장입니다.[325] 캐나다는 주로 경제 정책과 가족 통일에 의해 추진되는 [326]세계에서 가장 높은 1인당 이민율을 가지고 있습니다.[327][328] 2021년 캐나다에는 405,000명의 이민자가 들어왔습니다.[329] 캐나다는 난민 재정착에서 세계를 선도하고 있습니다. 2018년에 28,000명 이상을 재정착했습니다.[330] 새로운 이민자들은 주로 토론토, 몬트리올, 밴쿠버와 같은 미국의 주요 도시 지역에 정착합니다.[331]

캐나다의 인구 밀도는 평방 킬로미터당 4.2명으로 세계에서 가장 낮습니다.[323] 캐나다는 북위 83도에서 북위 41도까지 위도에 걸쳐 있으며 인구의 약 95%가 북위 55도 이남에서 발견됩니다.[332] 인구의 약 80 퍼센트가 미국과의 국경에서 150 킬로미터 (93 마일) 이내에 살고 있습니다.[333] 캐나다는 인구의 80% 이상이 도심에 살고 있을 정도로 고도로 도시화되어 있습니다.[334] 미국에서 거의 50%를 차지하는 인구밀도가 가장 높은 지역은 퀘벡 남부와 온타리오 주 남부의 오대호와 세인트로렌스 강을 따라 있는 퀘벡 시-윈저 코리더입니다.[335][332]

캐나다인의 대다수(81.1%)는 가족 가구에 살고 있고, 12.1%는 혼자 살고 있으며, 다른 친척이나 관련 없는 사람들과 함께 살고 있는 사람들은 6.8%로 보고되었습니다.[336] 자녀가 있거나 없는 부부 가구가 51%, 한부모 가구가 8.7%, 다세대 가구가 2.9%, 1인 가구가 29.3%입니다.[336]

| 순위 | 이름. | 지방 | 팝. | 순위 | 이름. | 지방 | 팝. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 토론토 | 온타리오. | 6,202,225 | 11 | 런던 | 온타리오. | 543,551 | ||

| 2 | 몬트리올 | 퀘벡 주 | 4,291,732 | 12 | 핼리팩스 | 노바스코샤 주 | 465,703 | ||

| 3 | 밴쿠버 | 브리티시컬럼비아 주 | 2,642,825 | 13 | 세인트캐서린스-나이아가라 | 온타리오. | 433,604 | ||

| 4 | 오타와가티노 | 온타리오-퀘벡 주 | 1,488,307 | 14 | 윈저 | 온타리오. | 422,630 | ||

| 5 | 캘거리 | 앨버타 주 | 1,481,806 | 15 | 오샤와 | 온타리오. | 415,311 | ||

| 6 | 에드먼턴 | 앨버타 주 | 1,418,118 | 16 | 빅토리아 | 브리티시컬럼비아 주 | 397,237 | ||

| 7 | 퀘벡 시 | 퀘벡 주 | 839,311 | 17 | 새스커툰 | 서스캐처원 주 | 317,480 | ||

| 8 | 위니펙 | 매니토바 주 | 834,678 | 18 | 레지나 | 서스캐처원 주 | 249,217 | ||

| 9 | 해밀턴 | 온타리오. | 785,184 | 19 | 셔브룩 | 퀘벡 주 | 227,398 | ||

| 10 | 키치너-캠브리지-워털루 | 온타리오. | 575,847 | 20 | 켈로나 | 브리티시컬럼비아 주 | 222,162 | ||

민족

2021년 캐나다 인구 조사에 따르면 450개 이상의 "민족 또는 문화적 기원"이 캐나다인에 의해 자가 보고되었습니다.[338] 선택된 주요 범민족 집단은 다음과 같습니다. 유럽 (52.5 퍼센트), 북미 (22.[338][339]9 퍼센트), 아시아 (19.3 퍼센트), 북미 원주민 (6.1 퍼센트), 아프리카 (3.8 퍼센트), 라틴, 중앙 및 남미 (2.5 퍼센트), 카리브 (2.1 퍼센트), 오세아니아 (0.3 퍼센트), 그리고 기타 (6 퍼센트). 60% 이상의 캐나다인이 단일 기원을 보고했고, 36%의 캐나다인이 다양한 민족적 기원을 가지고 있다고 보고했기 때문에 전체 합계는 100% 이상입니다.[338]

2021년 자체 보고된 10대 특정 민족 또는 문화적 기원은 캐나다[d](인구의 15.6%)였으며, 영어(14.7%), 아일랜드(12.1%), 스코틀랜드(12.1%), 프랑스어(11.0%), 독일어(8.1%), 중국어(4.7%), 이탈리아어(4.3%), 인도어(3.7%)가 그 뒤를 이었습니다. 그리고 우크라이나어(3.5%).[344]

2021년에 집계된 3,630만 명 중 약 2,540만 명이 "백인"으로 보고되었으며, 이는 인구의 69.8%를 차지합니다.[345] 2016년부터 2021년까지 5.3% 증가한 비토착 인구에 비해 5%(180만 명)에 해당하는 원주민 인구는 9.4% 증가했습니다.[345] 캐나다인 4명 중 1명 또는 인구의 26.5%가 비백인 및 비원주민 가시적 소수민족에 속했으며,[346][e] 2021년 그 중 가장 큰 소수민족은 남아시아인(260만 명; 7.1%), 중국인(170만 명; 4.7%), 흑인(150만 명; 4.3%)이었습니다.[348]

2011년과 2016년 사이에 가시적인 소수자 인구는 18.4% 증가했습니다.[349] 1961년, 캐나다 인구의 2%도 안 되는 약 30만 명의 사람들이 눈에 보이는 소수 집단의 구성원이었습니다.[350] 2021년 인구 조사에 따르면 인구의 거의 4분의 1(23.0%)에 해당하는 830만 명이 캐나다에서 토지 이민자 또는 영주권자로 신고했으며, 이는 1921년 인구 조사의 22.3%보다 높은 수치입니다.[351] 2021년 캐나다로 이주하는 이민자의 출신 국가 상위 3개국은 인도, 중국, 필리핀이었습니다.[352]

언어들

다양한 언어가 캐나다인에 의해 사용되며, 영어와 프랑스어(공용어)는 각각 약 54%와 19%의 캐나다인의 모국어입니다.[336] 2021년 인구 조사에 따르면 780만 명이 조금 넘는 캐나다인이 모국어로 비공식 언어를 나열했습니다. 가장 일반적인 비공식 모국어로는 북경어(679,255개의 제1언어 사용자), 펀자브어(666,585개), 광둥어(553,380개), 스페인어(538,870개), 아랍어(508,410개), 타갈로그어(461,150개), 이탈리아어(319,505개), 독일어(272,865개), 타밀어(237,890개) 등이 있습니다.[336] 캐나다 연방 정부는 캐나다의 권리와 자유의 헌장 제16조 및 연방 공용어법에 따라 공용어 담당자가 적용하는 공용어 이중언어를 실행합니다. 영어와 프랑스어는 연방 법원, 의회 및 모든 연방 기관에서 동등한 지위를 가지고 있습니다. 시민들은 충분한 수요가 있는 경우 영어나 프랑스어로 연방 정부 서비스를 받을 권리가 있으며, 공식 언어를 사용하는 소수자들은 모든 주와 지역에서 자신의 학교를 받을 수 있습니다.[354]

1974년 퀘벡 주의 공식 언어법에 따라 프랑스어가 퀘벡 주의 유일한 공식 언어가 되었습니다.[355] 프랑스어를 사용하는 캐나다인의 82% 이상이 퀘벡에 살고 있지만, 뉴브런즈윅, 앨버타, 매니토바에는 상당한 프랑스어 사용 인구가 있습니다. 온타리오 주는 퀘벡 외에 가장 많은 프랑스어 사용 인구를 가지고 있습니다.[356] 공식적으로 이중언어를 사용하는 유일한 지방인 뉴브런즈윅은 인구의 33%를 구성하는 프랑스어를 사용하는 아카디아 소수민족을 가지고 있습니다.[357] 노바스코샤 남서부, 브레튼 곶, 프린스에드워드 섬 중부와 서부에도 아카디아인 집단이 있습니다.[358]

다른 지방에는 이와 같은 공식 언어가 없지만 프랑스어는 영어 외에도 교육 언어, 법원 및 기타 정부 서비스로 사용됩니다. 매니토바 주, 온타리오 주, 퀘벡 주는 주 의회에서 영어와 프랑스어를 모두 사용할 수 있도록 허용하고 있으며 두 언어로 법률이 제정되어 있습니다. 온타리오 주에서 프랑스어는 일부 법적 지위를 가지고 있지만 완전히 공동 공식적이지는 않습니다.[359] 11개의 원주민 언어 그룹이 있으며 65개 이상의 독특한 언어와 방언으로 구성되어 있습니다.[360] 몇몇 원주민 언어들은 북서 영토에서 공식적인 지위를 가지고 있습니다.[361] 이누크티투어는 누나부트어의 주요 언어이며 누나부트어의 세 개의 공용어 중 하나입니다.[362]

게다가, 캐나다는 많은 수화의 본고장이고, 그 중 일부는 원주민입니다.[363] 미국 수화(ASL)는 초등학교와 중등학교에서 ASL의 보급으로 인해 전국에서 사용되고 있습니다.[364] 퀘벡 수화(LSQ)는 주로 퀘벡에서 사용됩니다.[365]

종교

캐나다는 종교적으로 다양하며, 광범위한 신념과 관습을 포괄합니다.[367] 캐나다 헌법은 하나님을 가리키며 군주는 신앙의 수호자라는 칭호를 달고 있지만 캐나다에는 공식적인 교회가 없고 정부는 공식적으로 종교 다원주의에 전념하고 있습니다.[368] 캐나다에서 종교의 자유는 헌법적으로 보호되는 권리로, 개인이 제한이나 간섭 없이 집회와 예배를 할 수 있도록 허용합니다.[369]

1970년대 이후 종교 준수율은 꾸준히 감소했습니다.[367] 한때 캐나다 문화와 일상 생활에 중심적이고 필수적인 역할을 했던 기독교가 쇠퇴하면서 [370]캐나다는 포스트 기독교, 세속 국가가 되었습니다.[371][372][373] 대다수의 캐나다인들은 일상생활에서 종교를 중요하지 않다고 생각하지만,[374] 그들은 여전히 하나님을 믿습니다.[375] 종교의 실천은 일반적으로 캐나다 사회 전체와 국가에 의해 사적인 문제로 여겨집니다.[376]

2021년 인구 조사에 따르면 기독교는 인구의 29.9%를 차지하는 로마 가톨릭 신자가 가장 많은 캐나다에서 가장 큰 종교입니다. 전체 인구의 53.3%를 차지하는 기독교인들이 [f]그 다음으로 종교가 없거나 있다고 보고하는 사람들이 34.6%로 뒤를 이었습니다.[379] 다른 종교로는 이슬람교 (4.9%), 힌두교 (2.3%), 시크교 (2.1%), 불교 (1.0%), 유대교 (0.9%), 원주민 영성 (0.2%) 등이 있습니다.[380] 캐나다는 인도 다음으로 두 번째로 많은 시크교도 인구를 가지고 있습니다.[381]

헬스

캐나다의 의료는 비공식적으로 메디케어(Medicare)라고 불리는 공적 자금을 지원받는 의료의 주 및 준주 시스템을 통해 전달됩니다.[382][383] 1984년[384] 캐나다 보건법의 규정에 의해 안내되며 보편적입니다.[385] 공적 자금을 지원받는 의료 서비스에 대한 보편적인 접근은 캐나다 사람들이 종종 "캐나다에 사는 모든 사람들에게 국가 의료 보험을 보장하는 근본적인 가치로 간주됩니다."[386] 캐나다 의료의 약 30%가 민간 부문을 통해 지불됩니다.[387] 이것은 처방약, 치과, 검안과 같이 메디케어가 보장하지 않거나 부분적으로 보장되지 않는 서비스에 대한 비용을 대부분 지불합니다.[387] 약 65~75%의 캐나다인들이 어떤 형태로든 보충 의료 보험을 가지고 있습니다; 많은 사람들이 그들의 고용주를 통해 그것을 받거나 2차 사회 서비스 프로그램에 접속합니다.[388][387]

다른 많은 선진국들과 공통적으로, 캐나다는 은퇴자가 많아지고 생산 연령이 낮은 인구로 인구가 이동함에 따라 의료비 지출이 증가하고 있습니다. 2021년 캐나다의 평균 연령은 41.9세였습니다.[336] 기대수명은 81.1세입니다.[389] 최고 공중 보건 책임자의 2016년 보고서에 따르면 G7 국가 중 인구 비율이 가장 높은 캐나다인의 88%가 "건강이 좋거나 매우 좋다"고 말했습니다.[390] 캐나다 성인의 80%는 흡연, 신체 활동 부족, 건강하지 못한 식사 또는 과도한 알코올 사용과 같은 만성 질환에 대한 적어도 한 가지 주요 위험 요소가 있다고 스스로 보고합니다.[391] 캐나다는 OECD 국가 중 성인 비만 비율이 가장 높은 국가 중 하나로, 약 270만 명의 당뇨병 발병에 기여하고 있습니다.[391] 캐나다 사망자의 65%는 암(사망의 주요 원인), 심혈관계 질환, 호흡기 질환, 당뇨병 등 4가지 만성질환에 의해 발생합니다.[392][393]

2021년 캐나다 보건정보연구소는 의료비 지출이 3,080억 달러, 즉 그해 캐나다 GDP의 12.7%에 달했다고 보고했습니다.[394] 2022년 캐나다의 1인당 의료비 지출은 OECD 의료 시스템 중 12위를 차지했습니다.[395] 캐나다는 2000년대 초반부터 대다수의 OECD 보건 지표에서 평균에 가깝거나 평균을 상회하는 성과를 거두었으며, 대기 시간 및 진료 접근성에 대한 OECD 지표에서 평균보다 높은 점수를 기록했으며, 의료의 질과 자원 사용에 대한 평균 점수를 받았습니다.[396][397] 코먼웰스 펀드의 2021년 보고서는 가장 선진화된 11개국의 의료 시스템을 비교한 결과 캐나다를 2위부터 꼴찌로 평가했습니다.[398] 확인된 약점은 비교적 높은 영아 사망률, 만성 질환의 유병률, 긴 대기 시간, 시간 외 치료의 열악한 가용성, 처방약 및 치과 보장 부족이었습니다.[398] 캐나다의 의료 시스템에서 증가하는 문제는 의료 전문가의 부족과 [399]병원의 수용 능력입니다.[400]

교육

캐나다의 교육은 대부분 연방, 지방 및 지방 정부에서 공공, 자금 및 감독을 제공합니다.[401] 교육은 도 관할권 내에 있으며 교육과정은 도에서 총괄하고 있습니다.[402][403] 캐나다의 교육은 일반적으로 초등교육과 중등교육, 후기 중등교육으로 나뉩니다. 영어와 프랑스어로 된 교육은 캐나다 전역의 대부분의 장소에서 가능합니다.[404] 캐나다에는 많은 수의 대학이 있으며, 거의 대부분의 대학이 공적 자금을 지원받고 있습니다.[405] 1663년에 설립된 라발 대학은 캐나다에서 가장 오래된 고등 교육 기관입니다.[406] 가장 큰 대학은 85,000명이 넘는 학생들이 있는 토론토 대학입니다.[407] 토론토 대학, 브리티시 컬럼비아 대학, 맥길 대학, 맥마스터 대학 등 4개 대학이 세계 100위권에 정기적으로 이름을 올리고 있으며, 총 18개 대학이 세계 500위권에 들었습니다.[408]

OECD의 2019년 보고서에 따르면 캐나다는 세계에서 가장 교육을 많이 받은 국가 중 하나이며,[409] 캐나다 성인의 56% 이상이 적어도 학부 대학 또는 대학 학위를 취득했습니다.[409] 캐나다는 GDP의 약 5.3%를 교육비로 지출하고 있습니다.[410] 이 나라는 고등교육에 많은 투자를 하고 있습니다 (학생 1인당 20,000 달러 이상).[411] 2014년[update] 현재, 25세에서 64세의 성인의 89%가 고등학교 학위와 동등한 수준의 학위를 취득한 반면, OECD 평균은 75%입니다.[412]

의무 교육 연령은 5-7세에서 16-18세 사이이며,[413] 성인 문해율 99%에 기여합니다.[414] 2016년 현재 국내에서 6만명이 조금 넘는 어린이들이 홈스쿨링을 받고 있습니다. 국제 학생 평가 프로그램은 캐나다 학생들이 OECD 평균, 특히 수학, 과학 및 독서 분야에서 매우 높은 성적을 [415][416]거두며 캐나다 15세 학생들의 전반적인 지식과 기술을 세계 6위로 평가하고 있음을 나타냅니다. 비록 이러한 점수는 최근 몇 년 동안 감소하고 있지만요. 캐나다는 읽기 문해력, 수학, 과학 분야에서 2015년 OECD 평균 493점에 비해 평균 학생 수가 523.7점으로 OECD 국가 중 우수한 성적을 보였습니다.[417][418]

문화

캐나다의 문화는 광범위한 구성국적으로부터 영향을 받고 "정의로운 사회"를 촉진하는 정책은 헌법적으로 보호됩니다.[420][421][422] 1960년대부터 캐나다는 모든 국민들에게 평등과 포용을 강조해 왔습니다.[423][424][425] 다문화주의의 공식적인 국가 정책은 종종 캐나다의 중요한 업적[426] 중 하나이자 캐나다 정체성의 주요한 구별 요소로 인용됩니다.[427][428] 퀘벡에는 문화적 정체성이 강하고 영국계 캐나다 문화와는 구별되는 프랑스계 캐나다 문화가 있습니다.[429] 전체적으로 캐나다는 이론적으로 지역 민족 하위 문화의 문화 모자이크입니다.[430][431][432]

선택적 이민, 사회 통합, 극우 정치 탄압 등을 근간으로 하는 다문화주의를 강조하는 캐나다의 거버넌스 접근법은 국민적 지지가 광범위합니다.[433] 공적 자금을 지원받는 의료, 부의 재분배를 위한 더 높은 세금, 사형제도의 불법화, 빈곤 퇴치를 위한 강력한 노력, 엄격한 총기 규제, 여성의 권리에 대한 사회적 자유주의적 태도(임신종기와 같은), LGBT 권리 등과 같은 정부 정책, 합법화된 안락사와 대마초 사용은 캐나다의 정치적, 문화적 가치를 보여주는 지표입니다.[434][435][436] 캐나다 사람들은 또한 캐나다의 대외 원조 정책, 평화 유지 역할, 국립 공원 시스템 및 캐나다 권리 및 자유 헌장에 동의합니다.[437][438]

역사적으로 캐나다는 영국, 프랑스, 원주민 문화와 전통의 영향을 받았습니다. 그들의 언어, 예술, 음악을 통해 원주민들은 캐나다의 정체성에 계속해서 영향을 미치고 있습니다.[439] 20세기 동안 아프리카, 카리브해 및 아시아 국적을 가진 캐나다인은 캐나다의 정체성과 문화에 추가되었습니다.[440]

기호

자연, 개척자, 포획자, 무역상 등의 주제는 캐나다 상징주의의 초기 발전에 중요한 역할을 했습니다.[442] 현대의 상징들은 그 나라의 지리, 추운 기후, 생활 양식, 그리고 전통적인 유럽과 토착의 상징들의 캐나다화를 강조합니다.[443] 단풍잎을 캐나다 상징으로 사용한 것은 18세기 초로 거슬러 올라갑니다. 단풍잎은 캐나다의 현재 및 이전 국기와 캐나다의 문장에 묘사되어 있습니다.[444] 단풍잎 타탄으로 알려진 캐나다의 공식 타탄은 계절에 따라 변화하는 단풍잎의 색깔을 반영하는 4가지 색상을 가지고 있습니다. 봄에는 녹색, 초가을에는 금색, 첫 서리에는 빨간색, 내린 후에는 갈색입니다.[445] 캐나다의 문장(Arms of Canada)은 영국의 문장을 본떠서 만든 것으로, 프랑스와 독특한 캐나다 요소가 영국 버전에서 파생된 것을 대체하거나 추가되었습니다.[446]

다른 중요한 상징들로는 국가 표어인 "A mariusque ad mare" ("From Sea to Sea"),[447] 아이스하키와 라크로스의 스포츠, 비버, 캐나다 거위, 커먼룬, 캐나다 말, 왕립 캐나다 기마 경찰, 캐나다 로키스,[444] 그리고 더 최근에는 토템 폴과 이누숙이 있습니다.[448] 캐나다 맥주, 메이플 시럽, 투크, 카누, 나나이모 바, 버터 타르트, 푸틴은 독특한 캐나다산으로 정의됩니다.[448][449] 캐나다 동전에는 이러한 상징들이 많이 있습니다: 1달러 동전에는 달이, 50개의 ¢ 조각에는 캐나다의 문장(Arms of Canada), 그리고 니켈에는 비버(Beaver)가 있습니다. 이전 군주인 엘리자베스 2세 여왕의 이미지가 20달러 지폐와 현재 캐나다 동전의 뒷면에 나타납니다.[450]

문학.

캐나다 문학은 프랑스와 영국의 문학 전통에 각각 뿌리를 둔 프랑스 문학과 영어 문학으로 종종 나뉩니다.[451] 가장 초기의 캐나다 이야기는 여행과 탐험에 관한 것이었습니다.[452] 이는 캐나다의 역사적 문헌 속에서 발견할 수 있는 세 가지 주요 주제, 즉 자연, 변경 생활, 그리고 세계 속에서의 캐나다의 위치로 진행되었으며, 이 세 가지 주제는 모두 수비 정신과 관련이 있습니다.[453] 최근 수십 년 동안 캐나다 문학은 전 세계에서 온 이민자들의 영향을 강하게 받았습니다.[454] 1990년대까지 캐나다 문학은 세계 최고 중 하나로 여겨졌습니다.[455]

두 개의 부커상을 받은 소설가, 시인, 문학평론가 마가렛 애트우드,[457] 영어로 단편소설의 살아있는 최고 작가로 불리는 노벨상 수상자 앨리스 먼로,[458] 그리고 부커상 수상자 마이클 온다트제를 [456]포함하여 수많은 캐나다 작가들이 국제 문학상을 축적했습니다. 아카데미 작품상을 수상한 동명의 영화로 각색된 '영어 환자'라는 소설을 쓴 사람은 누구일까요.[459] L. M. M. 몽고메리는 1908년에 그린 게이블의 앤과 함께 시작한 일련의 어린이 소설을 만들었습니다.[460]

미디어

캐나다의 미디어는 매우 자율적이고 검열되지 않으며 다양하고 매우 지역화되어 있습니다.[461][462] 방송법은 "이 제도는 캐나다의 문화적, 정치적, 사회적, 경제적 구조를 보호하고 풍부하게 하고 강화하는 역할을 해야 한다"고 선언합니다.[463] 캐나다는 잘 발달된 미디어 부문을 가지고 있지만, 특히 영어 영화, 텔레비전 쇼 및 잡지에서 문화적 산출물이 미국으로부터의 수입에 의해 가려지는 경우가 많습니다.[464] 그 결과 캐나다 방송국(CBC), 캐나다 국립 영화 위원회(NFB), 캐나다 라디오-텔레비전 및 통신 위원회(CRTC)와 같은 연방 정부 프로그램, 법률 및 기관에서 뚜렷한 캐나다 문화의 보존을 지원합니다.[465]

인쇄 및 디지털, 그리고 공식 언어로 된 캐나다의 대중 매체는 대부분 "한 손 안에 있는 기업"들에 의해 지배되고 있습니다.[466] 이 중 가장 큰 회사는 캐나다 국영 방송사인 캐나다 방송사로, 국내 문화 콘텐츠를 제작하고 영어와 프랑스어로 자체 라디오와 TV 네트워크를 운영하는 데도 상당한 역할을 하고 있습니다.[467] CBC 외에도 TV Ontario 및 Télé-Quebec과 같은 일부 지방 정부에서는 자체 교육 TV 방송 서비스를 제공합니다.[468]

영화와 텔레비전을 포함한 캐나다의 비뉴스 미디어 콘텐츠는 미국, 영국, 호주 및 프랑스로부터의 수입뿐만 아니라 현지 제작자에 의해 영향을 받습니다.[469] 외국산 미디어의 양을 줄이기 위한 노력으로 텔레비전 방송에 대한 정부 개입에는 콘텐츠 규제와 공적 자금 조달이 모두 포함될 수 있습니다.[470] 캐나다 세법은 잡지 광고에서 외국 경쟁을 제한합니다.[471]

시각예술

캐나다의 예술은 원주민들에 의해 수천 년 동안의 거주로 특징지어지며,[473] 후대에 예술가들은 영국, 프랑스, 원주민 및 미국의 예술 전통을 결합했으며 때로는 민족주의를 장려하기 위해 노력하면서 유럽 스타일을 수용했습니다.[474] 예술가들이 캐나다에서의 삶의 현실을 반영하기 위해 그들의 전통을 취하고 이러한 영향을 적응시켰기 때문에 캐나다 예술의 본질은 이러한 다양한 기원을 반영합니다.[475]

캐나다 정부는 캐나다 문화유산부를 통해 미술관에 보조금을 지급하는 [476]것은 물론 전국에 미술학교와 대학을 설립하고 자금을 지원하는 것, 캐나다 예술위원회를 통해 국가 공공예술기금, 예술가들을 돕는 것 등 캐나다 문화 발전에 역할을 해왔습니다. 미술관과 정기간행물, 그리고 따라서 캐나다의 문화적인 작품의 발전에 기여합니다.[477]

캐나다의 시각 예술은 화가 톰 톰슨이나 그룹 오브 세븐과 같은 인물들에 의해 지배되어 왔습니다.[478] 후자는 민족주의적이고 이상주의적인 화가들로 1920년 5월에 처음으로 그들의 독특한 작품을 전시했습니다. 7명의 멤버가 있는 것으로 알려졌지만, 로런 해리스, A. Y. 잭슨, 아서 리스머, J. E. H. 맥도널드, 프레드릭 발리 등 5명의 아티스트가 이 그룹의 아이디어를 발표하는 역할을 맡았습니다. 프랭크 존스턴(Frank Johnston)과 상업 예술가 프랭클린 카마이클(Franklin Carmichael)이 그들을 잠시 합류시켰습니다. A. J. 캐슨은 1926년에 그 그룹의 일원이 되었습니다.[479] 이 그룹과 관련된 또 다른 유명한 캐나다 예술가 에밀리 카(Emily Carr)는 태평양 북서부 해안의 원주민 풍경과 묘사로 유명합니다.[480]

음악

캐나다 음악은 다양한 지역 장면을 반영합니다.[482] 캐나다는 교회 홀, 회의실 홀, 음악원, 학원, 공연 예술 센터, 음반 회사, 라디오 방송국 및 텔레비전 뮤직 비디오 채널을 포함하는 방대한 음악 인프라를 개발했습니다.[483] 캐나다 음악 기금(Canada Music Fund)과 같은 정부 지원 프로그램은 독창적이고 다양한 캐나다 음악을 만들고 생산하고 마케팅하는 광범위한 음악가와 기업가를 돕습니다.[484] 캐나다 음악 산업은 정부의 계획과 규제뿐만 아니라 문화적 중요성으로 인해 세계적으로 유명한 작곡가, 음악가, 앙상블을 배출하는 [485]세계에서 가장 큰 산업 중 하나입니다.[486] 국내 음악 방송은 CRTC의 규제를 받습니다.[487] 캐나다 레코드 예술 과학 아카데미는 캐나다의 음악 산업상인 주노 어워드를 수여합니다.[488] 캐나다 음악 명예의 전당(Canadian Music Hall of Fame)은 캐나다 음악가들의 일생 동안의 업적을 기립니다.[489]

캐나다의 애국적인 음악은 200년 전으로 거슬러 올라갑니다. 캐나다 최초의 애국주의 음악 작품인 "The Bold Canadian"은 1812년에 쓰여졌습니다.[490] 1866년에 작곡된 "The Maple Leaf Forever"는 영국 캐나다 전역에서 인기 있는 애국적인 노래였으며 수년 동안 비공식 국가로 사용되었습니다.[491] "O Canada"는 또한 20세기의 대부분 동안 비공식 국가로 사용되었고 1980년에 공식 국가로 채택되었습니다.[492] 칼릭사 라발레(Calixa Lavallée)가 작곡한 이 음악은 시인이자 심사위원인 아돌프 바실 루티에(Sir Adolphe-Basile Ruthier)가 작곡한 애국시의 배경이었습니다. 이 텍스트는 1906년에 영어로 채택되기 전에는 원래 프랑스어로만 되어 있었습니다.[493]

스포츠

캐나다에서 조직화된 스포츠의 뿌리는 1770년대로 거슬러 올라가며,[495] 아이스하키, 라크로스, 컬링, 농구, 야구, 축구, 캐나다 축구의 주요 프로 경기의 개발과 대중화로 절정에 달합니다.[496] 캐나다의 공식 국가 스포츠는 아이스하키와 라크로스입니다.[497] 골프, 배구, 스키, 사이클, 수영, 배드민턴, 테니스, 볼링, 그리고 무술 공부와 같은 다른 스포츠들은 모두 청소년과 아마추어 수준에서 널리 즐깁니다.[498] 캐나다 스포츠의 위대한 업적은 캐나다의 스포츠 명예의 전당에서 인정받고 있습니다.[499] 캐나다에는 하키 명예의 전당과 같은 수많은 스포츠 "명예의 전당"이 있습니다.[499]

캐나다는 미국과 여러 주요 프로 스포츠 리그를 공유하고 있습니다.[500] 이 리그의 캐나다 팀은 내셔널 하키 리그의 7개 프랜차이즈와 메이저 리그 사커 3개 팀과 메이저 리그 야구와 전미 농구 협회 각각 1개 팀을 포함합니다. 다른 인기 있는 프로 대회로는 캐나다 풋볼 리그, 내셔널 라크로스 리그, 캐나다 프리미어 리그, 그리고 컬링 캐나다가 승인하고 조직한 다양한 컬링 대회가 있습니다.[501]

캐나다는 동계 올림픽과 하계 올림픽[502], 특히 "동계 스포츠 국가"로서 성공을 누렸고, 1976년 하계 올림픽,[503] 1988년 동계 올림픽,[504] 2010년 동계 올림픽,[505][506] 2015년 FIFA 여자 월드컵과 같은 세간의 이목을 끄는 국제 스포츠 행사를 여러 차례 개최했습니다.[507] 가장 최근에 캐나다는 2015 팬아메리칸 게임과 2015 파라판아메리칸 게임을 토론토에서 개최했습니다.[508] 이 나라는 멕시코, 미국과 함께 2026년 FIFA 월드컵을 공동 개최할 예정입니다.[509]

참고 항목

메모들

- ^ 인접한 48개 주를 통과하는 6,416 km(3,987 mi), 알래스카를[132] 통과하는 2,475 km(1,538 mi)

- ^ "브로커리지 정치: 캐나다의 성공적인 거대 텐트 정당들을 지칭하는 캐나다 용어로, 캐나다 중위 유권자들에게 어필하기 위해 중도적인 정책과 선거 연합을 채택하고 있습니다... 이념적 변방에 위치하지 않은 대다수 선거인들의 단기적 선호를 만족시키기 위해."[172]"[172][173]캐나다 정치의 전통적인 중개 모델은 이데올로기의 여지를 거의 남기지 않습니다."[174][175][176][177]

- ^ "캐나다 왕립 해군은 약 8,400명의 상근 선원과 5,100명의 비상근 선원으로 구성되어 있습니다. 육군은 약 22,800명의 상근 군인, 18,700명의 예비군, 5,000명의 캐나다 레인저로 구성되어 있습니다. 캐나다 왕립 공군은 약 13,000명의 정규군과 2,400명의 공군 예비군으로 구성되어 있습니다."[249]

- ^ 캐나다의 모든 시민은 캐나다 국적법에 의해 정의된 "캐나다인"으로 분류됩니다. "캐나다인"은 1996년부터 조상의 기원이나 혈통에 대한 인구조사 설문지에 추가되었습니다. 영어 설문지에는 "캐나다인"이, 프랑스어 설문지에는 "캐나다인"이 예시로 포함되었습니다.[341] "이 선택에 대한 응답자의 대다수는 가장 먼저 정착한 동부 지역 출신입니다. 응답자들은 일반적으로 눈에 띄게 유럽인(앵글로폰과 프랑코폰)이며 더 이상 민족 조상의 기원과 동일시하지 않습니다. 이러한 반응은 조상 계통과의 거리가 크거나 세대 간의 거리가 크기 때문입니다."[342][343]

- ^ 캐나다 통계청의 계산에서 원주민은 눈에 보이는 소수로 간주되지 않습니다. 캐나다 통계청은 "인종이 비백인이거나 피부색이 비백인 원주민을 제외한 사람"을 소수민족으로 정의합니다.[347]

- ^ 가톨릭교회(29.9%), 연합교회(3.3%), 성공회(3.1%), 동방정교회(1.7%), 침례교(1.2%), 오순절 및 기타 카리스마(1.1%), 세례자(0.4%), 여호와의증인(0.4%), 후기성도(0.2%), 루터교(0.9%), 감리교와 웨슬리아(성결)(0.3%), 장로교(0.8%), 개혁교(0.2%). 7.[377]6%는 단순히 "기독교인"으로 확인되었습니다.[378]

참고문헌

- ^ "Royal Anthem". Government of Canada. August 11, 2017. Archived from the original on December 6, 2020.

- ^ "Surface water and surface water change". OECD. Archived from the original on December 9, 2018. Retrieved October 11, 2020.

- ^ "Population estimates, quarterly". Statistics Canada. December 19, 2023. Archived from the original on December 19, 2023. Retrieved December 19, 2023.

- ^ "Census Profile, 2021 Census of Population". February 9, 2022. Archived from the original on February 9, 2022.

- ^ a b c d "World Economic Outlook Database, October 2023 Edition. (Canada)". International Monetary Fund. October 10, 2023. Archived from the original on October 13, 2023.

- ^ "Income inequality". OECD. Archived from the original on February 6, 2020. Retrieved July 16, 2021.

- ^ "Human Development Report 2021/2022" (PDF). United Nations Development Programme. September 8, 2022. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 8, 2022.

- ^ Olson, James Stuart; Shadle, Robert (1991). Historical Dictionary of European Imperialism. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 109. ISBN 978-0-313-26257-9.

- ^ a b c Rayburn, Alan (2001). Naming Canada: Stories about Canadian Place Names. University of Toronto Press. pp. 14–22. ISBN 978-0-8020-8293-0.

- ^ Magocsi, Paul R. (1999). Encyclopedia of Canada's Peoples. University of Toronto Press. p. 1048. ISBN 978-0-8020-2938-6.

- ^ "An Act to Re-write the Provinces of Upper and Lower Canada, and for the Government of Canada". J.C. Fisher & W. Kimble. 1841. p. 20.

- ^ O'Toole, Roger (2009). "Dominion of the Gods: Religious continuity and change in a Canadian context". In Hvithamar, Annika; Warburg, Margit; Jacobsen, Brian Arly (eds.). Holy Nations and Global Identities: Civil Religion, Nationalism, and Globalisation. Brill. p. 137. ISBN 978-90-04-17828-1.

- ^ Morra, Irene (2016). The New Elizabethan Age: Culture, Society and National Identity after World War II. I.B.Tauris. p. 49. ISBN 978-0-85772-867-8.

- ^ a b c d Buckner, Philip, ed. (2008). Canada and the British Empire. Oxford University Press. pp. 37–40, 56–59, 114, 124–125. ISBN 978-0-19-927164-1.

- ^ Courtney, John; Smith, David (2010). The Oxford Handbook of Canadian Politics. Oxford University Press. p. 114. ISBN 978-0-19-533535-4.

- ^ Dillehay, Thomas D. (2008). The Settlement of the Americas: A New Prehistory. Basic Books. p. 61. ISBN 978-0-7867-2543-4.

- ^ Fagan, Brian M.; Durrani, Nadia (2016). World Prehistory: A Brief Introduction. Routledge. p. 124. ISBN 978-1-317-34244-1.

- ^ Rawat, Rajiv (2012). Circumpolar Health Atlas. University of Toronto Press. p. 58. ISBN 978-1-4426-4456-4.

- ^ Hayes, Derek (2008). Canada: An Illustrated History. Douglas & Mcintyre. pp. 7, 13. ISBN 978-1-55365-259-5.

- ^ Macklem, Patrick (2001). Indigenous Difference and the Constitution of Canada. University of Toronto Press. p. 170. ISBN 978-0-8020-4195-1.

- ^ Sonneborn, Liz (January 2007). Chronology of American Indian History. Infobase Publishing. pp. 2–12. ISBN 978-0-8160-6770-1.

- ^ a b Graber, Christoph Beat; Kuprecht, Karolina; Lai, Jessica C. (2012). International Trade in Indigenous Cultural Heritage: Legal and Policy Issues. Edward Elgar Publishing. p. 366. ISBN 978-0-85793-831-2.

- ^ "Census Program Data Viewer dashboard". Statistics Canada. February 9, 2022. Retrieved February 3, 2024.

- ^ a b c Wilson, Donna M; Northcott, Herbert C (2008). Dying and Death in Canada. University of Toronto Press. pp. 25–27. ISBN 978-1-55111-873-4.

- ^ Thornton, Russell (2000). "Population history of Native North Americans". In Haines, Michael R; Steckel, Richard Hall (eds.). A population history of North America. Cambridge University Press. pp. 13, 380. ISBN 978-0-521-49666-7.

- ^ O'Donnell, C. Vivian (2008). "Native Populations of Canada". In Bailey, Garrick Alan (ed.). Indians in Contemporary Society. Handbook of North American Indians. Vol. 2. Government Printing Office. p. 285. ISBN 978-0-16-080388-8.

- ^ Marshall, Ingeborg (1998). A History and Ethnography of the Beothuk. McGill-Queen's University Press. p. 442. ISBN 978-0-7735-1774-5.

- ^ True Peters, Stephanie (2005). Smallpox in the New World. Marshall Cavendish. p. 39. ISBN 978-0-7614-1637-1.

- ^ Laidlaw, Z.; Lester, Alan (2015). Indigenous Communities and Settler Colonialism: Land Holding, Loss and Survival in an Interconnected World. Springer. p. 150. ISBN 978-1-137-45236-8.

- ^ Ray, Arthur J. (2005). I Have Lived Here Since The World Began. Key Porter Books. p. 244. ISBN 978-1-55263-633-6.

- ^ Preston, David L. (2009). The Texture of Contact: European and Indian Settler Communities on the Frontiers of Iroquoia, 1667–1783. University of Nebraska Press. pp. 43–44. ISBN 978-0-8032-2549-7.

- ^ Miller, J.R. (2009). Compact, Contract, Covenant: Aboriginal Treaty-Making in Canada. University of Toronto Press. p. 34. ISBN 978-1-4426-9227-5.

- ^ Williams, L. (2021). Indigenous Intergenerational Resilience: Confronting Cultural and Ecological Crisis. Routledge Studies in Indigenous Peoples and Policy. Taylor & Francis. p. 51. ISBN 978-1-000-47233-2.

- ^ Turner, N.J. (2020). Plants, People, and Places: The Roles of Ethnobotany and Ethnoecology in Indigenous Peoples' Land Rights in Canada and Beyond. McGill-Queen's Indigenous and Northern Studies. McGill-Queen's University Press. p. 14. ISBN 978-0-2280-0317-5.

- ^ Asch, Michael (1997). Aboriginal and Treaty Rights in Canada: Essays on Law, Equity, and Respect for Difference. UBC Press. p. 28. ISBN 978-0-7748-0581-0.

- ^ a b Commission de vérité et réconciliation du Canada (January 1, 2016). Canada's Residential Schools: The History, Part 1, Origins to 1939: The Final Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, Volume I. McGill-Queen's University Press. pp. 3–7. ISBN 978-0-7735-9818-8.

- ^ Lux, M.K. (2016). Separate Beds: A History of Indian Hospitals in Canada, 1920s-1980s. G - Reference, Information and Interdisciplinary Subjects Series. University of Toronto Press. p. 7. ISBN 978-1-4426-1386-7.

- ^ Kirmayer, Laurence J.; Guthrie, Gail Valaskakis (2009). Healing Traditions: The Mental Health of Aboriginal Peoples in Canada. UBC Press. p. 9. ISBN 978-0-7748-5863-2.

- ^ a b "Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada: Calls to Action" (PDF). National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation. 2015. p. 5. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 15, 2015.

- ^ "Principles respecting the Government of Canada's relationship with Indigenous peoples". Ministère de la Justice. July 14, 2017. Archived from the original on June 10, 2023.

- ^ Chapman, Frederick T. European Claims in North America in 1750. JSTOR community.15128627. Retrieved July 23, 2023.

- ^ Wallace, Birgitta (October 12, 2018). "Leif Eriksson". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on April 13, 2021. Retrieved June 4, 2020.

- ^ Johansen, Bruce E.; Pritzker, Barry M. (2007). Encyclopedia of American Indian History. ABC-CLIO. pp. 727–728. ISBN 978-1-85109-818-7.

- ^ a b Cordell, Linda S.; Lightfoot, Kent; McManamon, Francis; Milner, George (2009). "L'Anse aux Meadows National Historic Site". Archaeology in America: An Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. pp. 27, 82. ISBN 978-0-313-02189-3.

- ^ Blake, Raymond B.; Keshen, Jeffrey; Knowles, Norman J.; Messamore, Barbara J. (2017). Conflict and Compromise: Pre-Confederation Canada. University of Toronto Press. p. 19. ISBN 978-1-4426-3553-1.

- ^ Cartier, Jacques; Biggar, Henry Percival; Cook, Ramsay (1993). The Voyages of Jacques Cartier. University of Toronto Press. p. 26. ISBN 978-0-8020-6000-6.

- ^ Kerr, Donald Peter (1987). Historical Atlas of Canada: From the beginning to 1800. University of Toronto Press. p. 47. ISBN 978-0-8020-2495-4.

- ^ Baten, Jörg (2016). A History of the Global Economy. From 1500 to the Present. Cambridge University Press. p. 84. ISBN 978-1-107-50718-0.

- ^ Wynn, Graeme (2007). Canada and Arctic North America: An Environmental History. ABC-CLIO. p. 49. ISBN 978-1-85109-437-0.

- ^ Rose, George A (October 1, 2007). Cod: The Ecological History of the North Atlantic Fisheries. Breakwater Books. p. 209. ISBN 978-1-55081-225-1.

- ^ Kelley, Ninette; Trebilcock, Michael J. (September 30, 2010). The Making of the Mosaic: A History of Canadian Immigration Policy. University of Toronto Press. p. 27. ISBN 978-0-8020-9536-7.

- ^ LaMar, Howard Roberts (1977). The Reader's Encyclopedia of the American West. University of Michigan Press. p. 355. ISBN 978-0-690-00008-5.

- ^ Tucker, Spencer C; Arnold, James; Wiener, Roberta (September 30, 2011). The Encyclopedia of North American Indian Wars, 1607–1890: A Political, Social, and Military History. ABC-CLIO. p. 394. ISBN 978-1-85109-697-8.

- ^ Buckner, Phillip Alfred; Reid, John G. (1994). The Atlantic Region to Confederation: A History. University of Toronto Press. pp. 55–56. ISBN 978-0-8020-6977-1.

- ^ Hornsby, Stephen J (2005). British Atlantic, American frontier: spaces of power in early modern British America. University Press of New England. pp. 14, 18–19, 22–23. ISBN 978-1-58465-427-8.

- ^ Nolan, Cathal J (2008). Wars of the age of Louis XIV, 1650–1715: an encyclopedia of global warfare and civilization. ABC-CLIO. p. 160. ISBN 978-0-313-33046-9.

- ^ Allaire, Gratien (May 2007). "From 'Nouvelle-France' to 'Francophonie canadienne': a historical survey". International Journal of the Sociology of Language (185): 25–52. doi:10.1515/IJSL.2007.024. S2CID 144657353.

- ^ "The Death of General Wolfe". National Gallery of Canada. Archived from the original on July 26, 2023. Retrieved July 23, 2023.

- ^ Hicks, Bruce M (March 2010). "Use of Non-Traditional Evidence: A Case Study Using Heraldry to Examine Competing Theories for Canada's Confederation". British Journal of Canadian Studies. 23 (1): 87–117. doi:10.3828/bjcs.2010.5.

- ^ Hopkins, John Castell (1898). Canada: an Encyclopaedia of the Country: The Canadian Dominion Considered in Its Historic Relations, Its Natural Resources, its Material Progress and its National Development, by a Corps of Eminent Writers and Specialists. Linscott Publishing Company. p. 125.

- ^ Nellis, Eric (2010). An Empire of Regions: A Brief History of Colonial British America. University of Toronto Press. p. 331. ISBN 978-1-4426-0403-2.

- ^ Stuart, Peter; Savage, Allan M. (2011). The Catholic Faith and the Social Construction of Religion: With Particular Attention to the Québec Experience. WestBow Press. pp. 101–102. ISBN 978-1-4497-2084-1.

- ^ Leahy, Todd; Wilson, Raymond (September 30, 2009). Native American Movements. Scarecrow Press. p. 49. ISBN 978-0-8108-6892-2.

- ^ Newman, Peter C (2016). Hostages to Fortune: The United Empire Loyalists and the Making of Canada. Touchstone. p. 117. ISBN 978-1-4516-8615-9.

- ^ McNairn, Jeffrey L (2000). The capacity to judge. University of Toronto Press. p. 24. ISBN 978-0-8020-4360-3.

- ^ "Meeting Between Laura Secord and Lieut. Fitzgibbon, June 1813". Collection Search. July 13, 2023. Archived from the original on October 9, 2023.

- ^ Harrison, Trevor; Friesen, John W. (2010). Canadian Society in the Twenty-first Century: An Historical Sociological Approach. Canadian Scholars' Press. pp. 97–99. ISBN 978-1-55130-371-0.

- ^ Harris, Richard Colebrook; et al. (1987). Historical Atlas of Canada: The land transformed, 1800–1891. University of Toronto Press. p. 21. ISBN 978-0-8020-3447-2.

- ^ Gallagher, John A. (1936). "The Irish Emigration of 1847 and Its Canadian Consequences". CCHA Report: 43–57. Archived from the original on July 7, 2014.

- ^ Read, Colin (1985). Rebellion of 1837 in Upper Canada. McGill-Queen's University Press. p. 99. ISBN 978-0-7735-8406-8.

- ^ Romney, Paul (Spring 1989). "From Constitutionalism to Legalism: Trial by Jury, Responsible Government, and the Rule of Law in the Canadian Political Culture". Law and History Review. 7 (1): 121–174. doi:10.2307/743779. JSTOR 743779. S2CID 147047853.

- ^ Evenden, Leonard J; Turbeville, Daniel E (1992). "The Pacific Coast Borderland and Frontier". In Janelle, Donald G (ed.). Geographical Snapshots of North America. Guilford Press. p. 52. ISBN 978-0-89862-030-6.

- ^ Farr, DML; Block, Niko (August 9, 2016). "The Alaska Boundary Dispute". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on December 15, 2017.

- ^ "Territorial Evolution". Natural Resources Canada. September 12, 2016. Archived from the original on September 2, 2023.

- ^ Dijkink, Gertjan; Knippenberg, Hans (2001). The Territorial Factor: Political Geography in a Globalising World. Amsterdam University Press. p. 226. ISBN 978-90-5629-188-4.

- ^ Bothwell, Robert (1996). History of Canada Since 1867. Michigan State University Press. pp. 31, 207–310. ISBN 978-0-87013-399-2.

- ^ Bumsted, JM (1996). The Red River Rebellion. Watson & Dwyer. ISBN 978-0-920486-23-8.

- ^ "Railway History in Canada". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on April 29, 2023. Retrieved March 15, 2021.

- ^ a b "Building a nation". Canadian Atlas. Canadian Geographic. Archived from the original on March 3, 2006. Retrieved May 23, 2011.

- ^ Denison, Merrill (1955). The Barley and the Stream: The Molson Story. McClelland & Stewart Limited. p. 8.

- ^ "Sir John A. Macdonald". Library and Archives Canada. 2008. Archived from the original on June 14, 2011. Retrieved May 23, 2011.

- ^ Cook, Terry (2000). "The Canadian West: An Archival Odyssey through the Records of the Department of the Interior". The Archivist. Library and Archives Canada. Archived from the original on June 14, 2011. Retrieved May 23, 2011.

- ^ Hele, Karl S. (2013). The Nature of Empires and the Empires of Nature: Indigenous Peoples and the Great Lakes Environment. Wilfrid Laurier University Press. p. 248. ISBN 978-1-55458-422-2.

- ^ Gagnon, Erica. "Settling the West: Immigration to the Prairies from 1867 to 1914". Canadian Museum of Immigration. Archived from the original on November 28, 2020. Retrieved December 18, 2020.

- ^ Armitage, Derek; Plummer, Ryan (2010). Adaptive Capacity and Environmental Governance. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 183–184. ISBN 978-3-642-12194-4.

- ^ Daschuk, James William (2013). Clearing the Plains: Disease, Politics of Starvation, and the Loss of Aboriginal Life. University of Regina Press. pp. 99–104. ISBN 978-0-88977-296-0.

- ^ Hall, David John (2015). From Treaties to Reserves: The Federal Government and Native Peoples in Territorial Alberta, 1870–1905. McGill-Queen's University Press. pp. 258–259. ISBN 978-0-7735-4595-3.

- ^ Jackson, Robert J.; Jackson, Doreen; Koop, Royce (2020). Canadian Government and Politics (7th ed.). Broadview Press. p. 186. ISBN 978-1-4604-0696-0.

- ^ Tennyson, Brian Douglas (2014). Canada's Great War, 1914–1918: How Canada Helped Save the British Empire and Became a North American Nation. Scarecrow Press. p. 4. ISBN 978-0-8108-8860-9.

- ^ a b c d e f Morton, Desmond (1999). A military history of Canada (4th ed.). McClelland & Stewart. pp. 130–158, 173, 203–233, 258. ISBN 978-0-7710-6514-9.

- ^ Granatstein, J. L. (2004). Canada's Army: Waging War and Keeping the Peace. University of Toronto Press. p. 144. ISBN 978-0-8020-8696-9.

- ^ a b McGonigal, Richard Morton (1962). "Intro". The Conscription Crisis in Quebec – 1917: a Study in Canadian Dualism. Harvard University Press.

- ^ Morton, Frederick Lee (2002). Law, Politics and the Judicial Process in Canada. University of Calgary Press. p. 63. ISBN 978-1-55238-046-8.

- ^ Bryce, Robert B. (1986). Maturing in Hard Times: Canada's Department of Finance through the Great Depression. McGill-Queen's. p. 41. ISBN 978-0-7735-0555-1.

- ^ Mulvale, James P (July 11, 2008). "Basic Income and the Canadian Welfare State: Exploring the Realms of Possibility". Basic Income Studies. 3 (1). doi:10.2202/1932-0183.1084. S2CID 154091685.

- ^ Humphreys, Edward (2013). Great Canadian Battles: Heroism and Courage Through the Years. Arcturus Publishing. p. 151. ISBN 978-1-78404-098-7.

- ^ a b Goddard, Lance (2005). Canada and the Liberation of the Netherlands. Dundurn Press. pp. 225–232. ISBN 978-1-55002-547-7.

- ^ Bothwell, Robert (2007). Alliance and illusion: Canada and the world, 1945–1984. UBC Press. pp. 11, 31. ISBN 978-0-7748-1368-6.

- ^ Alfred Buckner, Phillip (2008). Canada and the British Empire. Oxford University Press. pp. 135–138. ISBN 978-0-19-927164-1.

- ^ Boyer, J. Patrick (1996). Direct Democracy in Canada: The History and Future of Referendums. Dundurn Press. p. 119. ISBN 978-1-4597-1884-5.

- ^ Mackey, Eva (2002). The house of difference: cultural politics and national identity in Canada. University of Toronto Press. p. 57. ISBN 978-0-8020-8481-1.

- ^ Landry, Rodrigue; Forgues, Éric (May 2007). "Official language minorities in Canada: an introduction". International Journal of the Sociology of Language (185): 1–9. doi:10.1515/IJSL.2007.022. S2CID 143905306.

- ^ Esses, Victoria M; Gardner, RC (July 1996). "Multiculturalism in Canada: Context and current status". Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science. 28 (3): 145–152. doi:10.1037/h0084934.

- ^ Sarrouh, Elissar (January 22, 2002). "Social Policies in Canada: A Model for Development" (PDF). Social Policy Series, No. 1. United Nations. pp. 14–16, 22–37. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 17, 2010.

- ^ "The Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms". Ministère de la Justice. March 15, 2021. Archived from the original on September 22, 2023.

- ^ "Proclamation of the Constitution Act, 1982". Government of Canada. May 5, 2014. Archived from the original on February 11, 2017.

- ^ "A statute worth 75 cheers". The Globe and Mail. March 17, 2009. Archived from the original on February 11, 2017.

- ^ Couture, Christa (January 1, 2017). "Canada is celebrating 150 years of... what, exactly?". Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. Archived from the original on February 10, 2017.

- ^ Trepanier, Peter (2004). "Some Visual Aspects of the Monarchical Tradition" (PDF). Canadian Parliamentary Review. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved February 10, 2017.

- ^ Bickerton, James; Gagnon, Alain, eds. (2004). Canadian Politics (4th ed.). Broadview Press. pp. 250–254, 344–347. ISBN 978-1-55111-595-5.

- ^ Légaré, André (2008). "Canada's Experiment with Aboriginal Self-Determination in Nunavut: From Vision to Illusion". International Journal on Minority and Group Rights. 15 (2–3): 335–367. doi:10.1163/157181108X332659. JSTOR 24674996.

- ^ Roberts, Lance W.; Clifton, Rodney A.; Ferguson, Barry (2005). Recent Social Trends in Canada, 1960–2000. McGill-Queen's University Press. p. 415. ISBN 978-0-7735-7314-7.

- ^ Munroe, HD (2009). "The October Crisis Revisited: Counterterrorism as Strategic Choice, Political Result, and Organizational Practice". Terrorism and Political Violence. 21 (2): 288–305. doi:10.1080/09546550902765623. S2CID 143725040.

- ^ a b Sorens, J (December 2004). "Globalization, secessionism, and autonomy". Electoral Studies. 23 (4): 727–752. doi:10.1016/j.electstud.2003.10.003.

- ^ Leblanc, Daniel (August 13, 2010). "A brief history of the Bloc Québécois". The Globe and Mail. Archived from the original on September 1, 2010.

- ^ Betz, Hans-Georg; Immerfall, Stefan (1998). The New Politics of the Right: Neo-Populist Parties and Movements in Established Democracies. St. Martin's Press. p. 173. ISBN 978-0-312-21134-9.

- ^ Schmid, Carol L. (2001). The Politics of Language: Conflict, Identity, and Cultural Pluralism in Comparative Perspective: Conflict, Identity, and Cultural Pluralism in Comparative Perspective. Oxford University Press. p. 112. ISBN 978-0-19-803150-5.

- ^ "Commission of Inquiry into the Investigation of the Bombing of Air India Flight 182". Government of Canada. Archived from the original on June 22, 2008. Retrieved May 23, 2011.

- ^ Sourour, Teresa K (1991). "Report of Coroner's Investigation" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on December 28, 2016. Retrieved March 8, 2017.

- ^ "The Oka Crisis". Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. 2000. Archived from the original on August 4, 2011. Retrieved May 23, 2011.

- ^ Roach, Kent (2003). September 11: consequences for Canada. McGill-Queen's University Press. pp. 15, 59–61, 194. ISBN 978-0-7735-2584-9.

- ^ Cohen, Lenard J.; Moens, Alexander (1999). "Learning the lessons of UNPROFOR: Canadian peacekeeping in the former Yugoslavia". Canadian Foreign Policy Journal. 6 (2): 85–100. doi:10.1080/11926422.1999.9673175.

- ^ Jockel, Joseph T; Sokolsky, Joel B (2008). "Canada and the war in Afghanistan: NATO's odd man out steps forward". Journal of Transatlantic Studies. 6 (1): 100–115. doi:10.1080/14794010801917212. S2CID 144463530.

- ^ Hehir, Aidan; Murray, Robert (2013). Libya, the Responsibility to Protect and the Future of Humanitarian Intervention. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 88. ISBN 978-1-137-27396-3.

- ^ Juneau, Thomas (2015). "Canada's Policy to Confront the Islamic State". Canadian Global Affairs Institute. Archived from the original on December 11, 2015. Retrieved December 10, 2015.

- ^ "Coronavirus disease (COVID-19)". Government of Canada. 2021. Archived from the original on June 13, 2021.

- ^ "Catholic group to release all records from Marievel, Kamloops residential schools". CTV News. June 25, 2021. Archived from the original on June 25, 2021.

- ^ Brescia, Michael M.; Super, John C. (2009). North America: An Introduction. University of Toronto Press. p. 38. ISBN 978-0-8020-9675-3.

- ^ Battram, Robert A. (2010). Canada in Crisis: An Agenda for Survival of the Nation. Trafford Publishing. p. 1. ISBN 978-1-4269-3393-6.

- ^ a b c d McColl, R. W. (September 2005). Encyclopedia of World Geography. Infobase Publishing. p. 135. ISBN 978-0-8160-5786-3.

- ^ "Geography". Statistics Canada. Archived from the original on July 19, 2018. Retrieved March 4, 2016.

- ^ a b "Boundary Facts". International Boundary Commission. Archived from the original on May 20, 2023. Retrieved May 20, 2023.

- ^ Chase, Steven (June 10, 2022). "Canada and Denmark reach settlement over disputed Arctic island, sources say". The Globe and Mail. Archived from the original on June 12, 2022.

- ^ Gallay, Alan (2015). Colonial Wars of North America, 1512–1763: An Encyclopedia. Taylor & Francis. p. 429. ISBN 978-1-317-48718-0.

- ^ Canadian Geographic. Royal Canadian Geographical Society. 2008. p. 20.

- ^ "Physiographic Regions of Canada". The Atlas of Canada. Natural Resources Canada. September 12, 2016. Archived from the original on June 21, 2021.

- ^ Bailey, William G; Oke, TR; Rouse, Wayne R (1997). The surface climates of Canada. McGill-Queen's University Press. p. 124. ISBN 978-0-7735-1672-4.

- ^ "Physical Components of Watersheds". The Atlas of Canada. December 5, 2012. Archived from the original on December 5, 2012.

- ^ Sandford, Robert William (2012). Cold Matters: The State and Fate of Canada's Fresh Water. Biogeoscience Institute at the University of Calgary. p. 11. ISBN 978-1-927330-20-3.

- ^ Etkin, David; Haque, CE; Brooks, Gregory R (April 30, 2003). An Assessment of Natural Hazards and Disasters in Canada. Springer. pp. 569, 582, 583. ISBN 978-1-4020-1179-5.

- ^ "Statistics, Regina SK". The Weather Network. Archived from the original on January 5, 2009. Retrieved January 18, 2010.

- ^ "Regina International Airport". Canadian Climate Normals 1981–2010. Environment Canada. September 25, 2013. Archived from the original on May 18, 2015.

- ^ Bush, E.; Lemmen, D.S. (2019). "Canada's Changing Climate Report" (PDF). Government of Canada. p. 84. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 22, 2019.

- ^ Zhang, X.; Flato, G.; Kirchmeier-Young, M.; Vincent, L.; Wan, H.; Wang, X.; Rong, R.; Fyfe, J.; Li, G. (2019). Bush, E.; Lemmen, D.S. (eds.). "Changes in Temperature and Precipitation Across Canada; Chapter 4" (PDF). Canada's Changing Climate Report. Government of Canada. pp. 112–193. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 18, 2020.

- ^ Boyd, David R (2011). Unnatural Law: Rethinking Canadian Environmental Law and Policy. UBC Press. pp. 67–69. ISBN 978-0-7748-4063-7.

- ^ "Terrestrial ecozones and ecoprovinces of Canada". Statistics Canada. January 12, 2018. Archived from the original on September 2, 2023.

- ^ "Introduction to the Ecological Land Classification (ELC) 2017". Statistics Canada. January 10, 2018. Archived from the original on November 16, 2020.

- ^ "Wild Species 2015: The General Status of Species in Canada" (PDF). National General Status Working Group: 1. Canadian Endangered Species Conservation Council. 2016. p. 2. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 27, 2021.

The new estimate indicates that there are about 80,000 known species in Canada, excluding viruses and bacteria

- ^ "Canada: Main Details". Convention on Biological Diversity. Archived from the original on August 10, 2022. Retrieved August 10, 2022.

- ^ "COSEWIC Annual Report". Species at Risk Public Registry. 2019. Archived from the original on March 5, 2021.

- ^ "Wild Species 2000: The General Status of Species in Canada". Conservation Council. 2001. Archived from the original on October 16, 2021.

- ^ "State of Canada's Biodiversity Highlighted in New Government Report". October 22, 2010. Archived from the original on January 22, 2021.

- ^ Raven, Peter H.; Berg, Linda R.; Hassenzahl, David M. (2012). Environment. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 1–3. ISBN 978-0-470-94570-4.

- ^ National Atlas of Canada. Natural Resources Canada. 2005. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-7705-1198-2.

- ^ Luckert, Martin K.; Haley, David; Hoberg, George (2012). Policies for Sustainably Managing Canada's Forests: Tenure, Stumpage Fees, and Forest Practices. UBC Press. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-7748-2069-1.

- ^ a b "Canada's conserved areas". Environment and Climate Canada. 2020. Archived from the original on April 2, 2022.

- ^ "The Mountain Guide – Banff National Park" (PDF). Parks Canada. 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 15, 2006.

- ^ Price, Martin F. (2013). Mountain Area Research and Management: Integrated Approaches. Earthscan. pp. 217–218. ISBN 978-1-84977-201-3.

- ^ "Algonquin Provincial Park Management Plan". Queen's Printer for Ontario. 1998. Archived from the original on February 9, 2021.

- ^ "Spotlight on Marine Protected Areas in Canada". Fisheries and Oceans Canada. December 13, 2017. Archived from the original on April 13, 2021.

- ^ "Scott Islands Marine National Widllife Area". Protected Planet. Retrieved September 25, 2020.

- ^ "Proposed Scott Islands Marine National Wildlife Area: regulatory strategy". Environment and Climate Change Canada. February 7, 2013. Archived from the original on January 23, 2021.

- ^ "UNESCO Biosphere Reserves of Canada". e CanadianBiosphere Reserves Association and the Canadian Commission for UNESCO. 2018. Archived from the original on January 26, 2021. 2021년 7월 5일 Wayback Machine에서 PDF 아카이브

- ^ "2021 Democracy Index" (PDF). Economist Intelligence Unit. 2021. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 20, 2022.

- ^ Westhues, Anne; Wharf, Brian (2014). Canadian Social Policy: Issues and Perspectives. Wilfrid Laurier University Press. pp. 10–11. ISBN 978-1-55458-409-3.

- ^ Bickerton, James; Gagnon, Alain (2009). Canadian Politics. University of Toronto Press. p. 56. ISBN 978-1-4426-0121-5.

- ^ Johnson, David (2016). Thinking Government: Public Administration and Politics in Canada (4th ed.). University of Toronto Press. pp. 13–23. ISBN 978-1-4426-3521-0.

- ^ McQuaig, L. (2010). Holding the Bully's Coat: Canada and the U.S. Empire. Doubleday Canada. p. 14. ISBN 978-0-385-67297-9.

- ^ Fierlbeck, Katherine (2006). Political Thought in Canada: An Intellectual History. University of Toronto Press. p. 87. ISBN 978-1-55111-711-9.

- ^ Dixon, John; P. Scheurell, Robert (March 17, 2016). Social Welfare in Developed Market Countries. Routledge. p. 48. ISBN 978-1-317-36677-5.

- ^ Boughey, Janina (2017). Human Rights and Judicial Review in Australia and Canada: The Newest Despotism?. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 105. ISBN 978-1-5099-0788-5.

- ^ Marland, Alex; Giasson, Thierry; Lees-Marshment, Jennifer (2012). Political Marketing in Canada. UBC Press. p. 257. ISBN 978-0-7748-2231-2.

- ^ Courtney, John; Smith, David (2010). The Oxford Handbook of Canadian Politics. Oxford University Press. p. 195. ISBN 978-0-19-533535-4.

- ^ Cochrane, Christopher (2010). "Left/Right Ideology and Canadian Politics". Canadian Journal of Political Science / Revue Canadienne de Science Politique. 43 (3): 583–605. doi:10.1017/S0008423910000624. JSTOR 40983510. S2CID 154420921.

- ^ Brooks, Stephen (2004). Canadian Democracy: An Introduction. Oxford University Press. p. 265. ISBN 978-0-19-541806-4.

Two historically dominant political parties have avoided ideological appeals in favour of a flexible centrist style of politics that is often labelled brokerage politics

- ^ Smith, Miriam (2014). Group Politics and Social Movements in Canada: Second Edition. University of Toronto Press. p. 17. ISBN 978-1-4426-0695-1.

Canada's party system has long been described as a "brokerage system" in which the leading parties (Liberal and Conservative) follow strategies that appeal across major social cleavages in an effort to defuse potential tensions.

- ^ Johnson, David (2016). Thinking Government: Public Administration and Politics in Canada, Fourth Edition. University of Toronto Press. pp. 13–23. ISBN 978-1-4426-3521-0.

...most Canadian governments, especially in the federal sphere, have taken a moderate, centrist approach to decision making, seeking to balance growth, stability, and governmental efficiency and economy...

- ^ Bittner, Amanda; Koop, Royce (March 1, 2013). Parties, Elections, and the Future of Canadian Politics. UBC Press. p. 300. ISBN 978-0-7748-2411-8.

- ^ Johnston, Richard (April 13, 2021). "The baffling history of Canada's party system". Policy Options. Archived from the original on December 9, 2022.

- ^ a b Gill, Jessica K. (December 20, 2021). "Unpacking the Role of Neoliberalism on the Politics of Poverty Reduction Policies in Ontario, Canada: A Descriptive Case Study and Critical Analysis". Social Sciences. MDPI AG. 10 (12): 485. doi:10.3390/socsci10120485. ISSN 2076-0760.

- ^ Evans, Geoffrey; de Graaf, Nan Dirk (2013). Political Choice Matters: Explaining the Strength of Class and Religious Cleavages in Cross-National Perspective. Oxford University Press. pp. 166–167. ISBN 978-0-19-966399-6.

- ^ Johnston, Richard (2017). The Canadian Party System: An Analytic History. UBC Press. ISBN 978-0-7748-3610-4.

- ^ "Election 2015 roundup". Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. Archived from the original on October 22, 2015.

- ^ Ambrose, Emma; Mudde, Cas (2015). "Canadian Multiculturalism and the Absence of the Far Right". Nationalism and Ethnic Politics. 21 (2): 213–236. doi:10.1080/13537113.2015.1032033. S2CID 145773856.

- ^ Taub, Amanda (June 27, 2017). "Canada's Secret to Resisting the West's Populist Wave". The New York Times. ISSN 1553-8095. OCLC 1645522. Archived from the original on June 27, 2017. Retrieved September 25, 2023.

- ^ Geddes, John (February 8, 2022). "What's actually standing in the way of right-wing populism in Canada?". Macleans.ca. Archived from the original on October 31, 2022.

- ^ Dowding, Keith; Dumont, Patrick (2014). The Selection of Ministers around the World. Taylor & Francis. p. 395. ISBN 978-1-317-63444-7.

- ^ "Constitution Act, 1867: Preamble". Queen's Printer. March 29, 1867. Archived from the original on February 3, 2010.

- ^ Smith, David E (June 10, 2010). "The Crown and the Constitution: Sustaining Democracy?" (PDF). The Crown in Canada: Present Realities and Future Options. Queen's University. p. 6. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 17, 2010.

- ^ a b MacLeod, Kevin S (2012). A Crown of Maples (PDF) (2nd ed.). Queen's Printer for Canada. p. 16. ISBN 978-0-662-46012-1. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 5, 2016. Retrieved March 8, 2017.

- ^ Johnson, David (2018). Battle Royal: Monarchists vs. Republicans and the Crown of Canada. Dundurn Press. p. 196. ISBN 978-1-4597-4015-0.

- ^ "The Governor General of Canada: Roles and Responsibilities". Queen's Printer. Archived from the original on September 15, 2018. Retrieved May 23, 2011.

- ^ Commonwealth public administration reform 2004. Commonwealth Secretariat. 2004. pp. 54–55. ISBN 978-0-11-703249-1.

- ^ a b c Forsey, Eugene (2005). How Canadians Govern Themselves (PDF) (6th ed.). Queen's Printer. pp. 1, 16, 26. ISBN 978-0-662-39689-5. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 29, 2009. Retrieved May 23, 2011.

- ^ a b Marleau, Robert; Montpetit, Camille. "House of Commons Procedure and Practice: Parliamentary Institutions". Queen's Printer. Archived from the original on August 28, 2011. Retrieved May 23, 2011.

- ^ Edwards, Peter (November 4, 2015). "'A cabinet that looks like Canada:' Justin Trudeau pledges government built on trust". Toronto Star. Archived from the original on January 28, 2017.

- ^ Johnson, David (2006). Thinking government: public sector management in Canada (2nd ed.). University of Toronto Press. pp. 134–135, 149. ISBN 978-1-55111-779-9.

- ^ "The Opposition in a Parliamentary System". Library of Parliament. Archived from the original on November 25, 2010. Retrieved May 23, 2011.

- ^ "Restoring and modernizing the West Block". Public Services and Procurement Canada. August 15, 2023. Archived from the original on October 22, 2023.

- ^ McWhinney, Edward Watson (October 8, 2019). "Sovereignty". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on May 29, 2023.

- ^ "About Elections and Ridings". Library of Parliament. Archived from the original on December 24, 2016. Retrieved September 3, 2016.

- ^ O'Neal, Brian; Bédard, Michel; Spano, Sebastian (April 11, 2011). "Government and Canada's 41st Parliament: Questions and Answers". Library of Parliament. Archived from the original on May 22, 2011.

- ^ Griffiths, Ann L.; Nerenberg, Karl (2003). Handbook of Federal Countries. McGill-Queen's University Press. p. 116. ISBN 978-0-7735-7047-4.

- ^ "Difference between Canadian Provinces and Territories". Intergovernmental Affairs Canada. 2010. Archived from the original on December 1, 2015. Retrieved November 23, 2015.

- ^ "Differences from Provincial Governments". Legislative Assembly of the Northwest Territories. 2008. Archived from the original on February 3, 2014. Retrieved January 30, 2014.

- ^ Watts, George S. (1993). Bank of Canada/La Banque du Canada: Origines et premieres annees/Origins and Early History. McGill-Queen's University Press. ISBN 978-0-88629-182-2. JSTOR j.ctt9qf36m.

- ^ "About". Statistics Canada. 2014. Archived from the original on January 15, 2015. Retrieved March 8, 2017.

- ^ Gilbert, Emily; Helleiner, Eric (2003). Nation-States and Money: The Past, Present and Future of National Currencies. Routledge. p. 39. ISBN 978-1-134-65817-6.

- ^ Cuhaj, George S.; Michael, Thomas (2011). Coins of the World: Canada. Krause Publications. p. 4. ISBN 978-1-4402-3129-2.

- ^ Dodek, Adam (2016). The Canadian Constitution. Dundurn – University of Ottawa Faculty of Law. p. 13. ISBN 978-1-4597-3505-7.

- ^ Olive, Andrea (2015). The Canadian Environment in Political Context. University of Toronto Press. pp. 41–42. ISBN 978-1-4426-0871-9.

- ^ Bhagwan, Vishnoo; Vidya, Bhushan (2004). World Constitutions. Sterling Publishers. pp. 549–550. ISBN 978-81-207-1937-8.

- ^ Bakan, Joel; Elliot, Robin M (2003). Canadian Constitutional Law. Emond Montgomery Publications. pp. 3–8, 683–687, 699. ISBN 978-1-55239-085-6.

- ^ "Current and Former Chief Justices". Supreme Court of Canada. December 18, 2017. Archived from the original on January 16, 2018.

- ^ Law, Politics, and the Judicial Process in Canada, 4th Edition (4 ed.). University of Calgary Press. 2018. pp. 117–172. doi:10.2307/j.ctv56fggn. ISBN 978-1-55238-990-4. JSTOR j.ctv56fggn. S2CID 240317161.

- ^ Yates, Richard; Bain, Penny; Yates, Ruth (2000). Introduction to Law in Canada. Prentice Hall Allyn and Bacon Canada. p. 93. ISBN 978-0-13-792862-0.

- ^ Hermida, Julian (May 9, 2018). Criminal Law in Canada. Kluwer Law International B.V. pp. 10–. ISBN 978-90-411-9627-9.

- ^ Sworden, Philip James (2006). An introduction to Canadian law. Emond Montgomery Publications. pp. 22, 150. ISBN 978-1-55239-145-7.

- ^ "Who we are". Ontario Provincial Police. 2009. Archived from the original on August 26, 2016. Retrieved October 24, 2012.

- ^ Sullivan, L.E. (2005). Encyclopedia of Law Enforcement. SAGE Publications. p. 995. ISBN 978-0-7619-2649-8.

- ^ Reynolds, Jim (2015). Aboriginal Peoples and the Law: A Critical Introduction. UBC Press. ISBN 978-0-7748-8023-7.

- ^ a b Patterson, Lisa Lynne (2004). Aboriginal roundtable on Kelowna Accord: Aboriginal policy negotiations 2004–2006 (PDF) (Report). 1. Parliamentary Information and Research Service, Library of Parliament. p. 3. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 26, 2014. Retrieved October 23, 2014.

- ^ "Treaty areas". Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat. October 7, 2002. Archived from the original on January 7, 2009.

- ^ Isaac, Thomas (2012). Aboriginal Law (4th ed.). UBC Press. p. 349. ISBN 978-1-895830-65-1.

- ^ Madison, Gary Brent (2000). Is There a Canadian Philosophy?: Reflections on the Canadian Identity. University of Ottawa Press. p. 128. ISBN 978-0-7766-0514-2.

- ^ a b "Diplomatic Missions and Consular Posts Accredited to Canada". GAC. June 10, 2014. Retrieved February 26, 2024.

- ^ a b Chapnick, Adam (2011). The Middle Power Project: Canada and the Founding of the United Nations. UBC Press. pp. 2–5. ISBN 978-0-7748-4049-1.

- ^ Gabryś, M.; Soroka, T. (2017). Canada as a selective power: Canada's Role and International Position after 1989. Societas. Neriton, Wydawnictwo. p. 39. ISBN 978-83-7638-792-5.

- ^ Sens, Allen; Stoett, Peter (2013). Global Politics (5th ed.). Nelson Education. p. 6. ISBN 978-0-17-648249-7.

- ^ "Plans at a glance and operating context". Global Affairs Canada. Archived from the original on September 25, 2020. Retrieved August 4, 2020.

- ^ Sorenson, David S.; Wood, Pia Christina (2005). The Politics of Peacekeeping in the Post-cold War Era. Psychology Press. p. 158. ISBN 978-0-7146-8488-8.

- ^ Sobel, Richard; Shiraev, Eric; Shapiro, Robert (2002). International Public Opinion and the Bosnia Crisis. Lexington Books. p. 21. ISBN 978-0-7391-0480-4.

- ^ "Canada and the Sustainable Development Goals". Social Development Canada. February 16, 2021. Archived from the original on November 21, 2023.

- ^ a b Lowenthal, M.M. (2019). Intelligence: From Secrets to Policy. SAGE Publications. pp. 480, 482. ISBN 978-1-5443-5836-9.

- ^ "Canada and the United States". The Canadian Encyclopedia. June 11, 2020. Archived from the original on October 29, 2023.

- ^ Nord, D.C.; Weller, G.R. Canada and the United States: An Introduction to a Complex Relationship. p. 14.

- ^ Carment, D.; Sands, C. (2019). Canada–US Relations: Sovereignty or Shared Institutions?. Canada and International Affairs. Springer International Publishing. pp. 3–10. ISBN 978-3-030-05036-8.

- ^ Haglung, David G (Autumn 2003). "North American Cooperation in an Era of Homeland Security". Orbis. 47 (4): 675–691. doi:10.1016/S0030-4387(03)00072-3.

- ^ Morrison, Katherine L. (2008). "The Only Canadians: Canada's French and the British Connection". International Journal of Canadian Studies (in French). Consortium Erudit (37): 177. doi:10.7202/040800ar. ISSN 1180-3991.

- ^ James, Patrick (2006). Michaud, Nelson; O'Reilly, Marc J (eds.). Handbook of Canadian Foreign Policy. Lexington Books. pp. 213–214, 349–362. ISBN 978-0-7391-1493-3.

- ^ Finkel, Alvin (1997). Our Lives: Canada after 1945. Lorimer. pp. 105–107, 111–116. ISBN 978-1-55028-551-2.

- ^ Holloway, Steven Kendall (2006). Canadian Foreign Policy: Defining the National Interest. University of Toronto Press. pp. 102–103. ISBN 978-1-55111-816-1.

- ^ Mays, Terry M. (December 16, 2010). Historical Dictionary of Multinational Peacekeeping. Scarecrow Press. pp. 218–. ISBN 978-0-8108-7516-6.

- ^ "Canada and Peacekeeping". The Canadian Encyclopedia. June 30, 2013. Retrieved February 26, 2024.