뉴질랜드

New Zealand뉴질랜드 아오테아로아 (마오리) | |

|---|---|

| 항목: "신이 뉴질랜드를 지켜주신다" (마오리: 아오테아로아) "신이여 왕을 구하소서"[n 1] | |

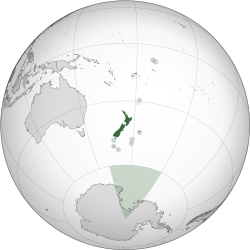

외딴 섬을 포함한 뉴질랜드의 위치, 남극에서의 영유권 주장, 토켈라우 | |

| 자본의 | 웰링턴 41°18'S 174°47'E / 41.300°S 174.783°E |

| 가장 큰 도시 | 오클랜드 |

| 공용어 | |

| 민족 | |

| 종교 (2018)[4] | |

| 성명서 | |

| 정부 | 단일 의회 입헌 군주제 |

• 군주 | 샤를 3세 |

• 총독부 | 신디 키로 |

• 수상 | 크리스토퍼 룩슨 |

| 입법부 | 의회. (의원) |

| 독립단계 | |

| 1840년 2월 6일 | |

• 책임정부 | 1856년 5월 7일 |

• 도미니언 | 1907년 9월 26일 |

| 1947년 11월 25일 | |

• 1986년 헌법 | 1987년1월1일 |

| 지역 | |

• 합계 | 268,021[6] km2 (103,483 sq mi) (75th) |

• 물(%) | 1.6[n 5] |

| 인구. | |

• 2024년 2월 견적 | |

• 2018년 인구조사 | |

• 밀도 | 19.5/km2 (50.5/sq mi) (167th) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2023년 견적 |

• 합계 | 2,799억 183 (63위) |

• 인당 | |

| GDP (nominal) | 2023년 견적 |

• 합계 | |

• 인당 | |

| 지니 (2022) | 중간의 |

| HDI (2021) | 매우 높은 · 13위 |

| 통화 | 뉴질랜드 달러($)(NZD) |

| 시간대 | UTC+12 (NZST[n 6]) |

• 여름(DST) | UTC+13 (NZDT[n 7]) |

| 날짜 형식 | dd/mm/yyyy[14] |

| 주행측 | 왼쪽 |

| 호출부호 | +64 |

| ISO 3166 코드 | NZ |

| 인터넷 TLD | .nz |

뉴질랜드(마오리: 아오테아로아(Aotaroa, a ɔˈ ɛ a ɾɔ a)는 태평양 남서부에 있는 섬나라입니다. 이 섬은 북섬(테 이카아마우이)과 남섬(테 와이포우나무)의 두 개의 주요 육지 덩어리와 700개가 넘는 작은 섬으로 구성되어 있습니다. 이 섬은 면적으로 여섯 번째로 큰 섬나라이며 태즈먼 해를 가로질러 호주의 동쪽과 뉴칼레도니아, 피지, 통가 섬의 남쪽에 위치해 있습니다. 남알프스 산맥을 포함한 이 나라의 다양한 지형과 날카로운 산봉우리는 지각의 융기와 화산 폭발에 많은 빚을 지고 있습니다. 뉴질랜드의 수도는 웰링턴이고, 가장 인구가 많은 도시는 오클랜드입니다.

뉴질랜드의 섬들은 인간이 거주할 수 있는 마지막 넓은 땅이었습니다. 약 1280년에서 1350년 사이에 폴리네시아인들은 섬에 정착하기 시작했고 그 후 독특한 마오리 문화를 발전시켰습니다. 1642년, 네덜란드의 탐험가 아벨 태즈먼은 뉴질랜드를 발견하고 기록한 최초의 유럽인이 되었습니다. 1840년, 영국과 마오리 족장의 대표들은 와이탕기 조약에 서명했고, 그 조약은 그 섬들에 대한 영국의 주권을 선언했습니다. 1841년, 뉴질랜드는 대영제국 내의 식민지가 되었습니다. 이후 식민지 정부와 마오리 부족 간의 일련의 갈등으로 마오리 땅이 대량으로 소외되고 몰수되는 사태가 벌어졌습니다. 뉴질랜드는 1907년에 자치령이 되었고 1947년에 완전한 법적 독립을 얻어 군주를 국가 원수로 유지했습니다. 오늘날 뉴질랜드 인구 525만 명의 대다수는 유럽계이며 토착민인 마오리족이 가장 많고 아시아인과 태평양 섬 주민이 그 뒤를 이습니다. 이를 반영하듯 뉴질랜드의 문화는 주로 마오리족과 초기 영국 정착민들로부터 유래하며, 최근에는 이민 증가로 인한 문화의 폭이 넓어지고 있습니다. 공용어는 영어, 마오리어, 뉴질랜드 수화이며 영어의 지역 방언이 지배적입니다.

선진국, 최저임금을 최초로 도입했고, 여성에게 선거권을 준 최초의 국가였습니다. 그것은 삶의 질, 인권에 대한 국제적인 측정에서 매우 높은 순위를 차지하고 있으며, 인식된 부패 수준이 낮습니다. 마오리족과 유럽인 사이에 구조적 차이가 있는 눈에 보이는 수준의 불평등을 유지하고 있습니다. 뉴질랜드는 1980년대에 큰 경제적 변화를 겪었고, 이는 뉴질랜드를 보호주의에서 자유화된 자유무역 경제로 변화시켰습니다. 서비스 부문이 국가 경제를 지배하고 산업 부문과 농업이 그 뒤를 이으며, 국제 관광도 중요한 수입원입니다.

국가적으로 입법 권한은 선출된 단원제 의회에 있으며, 행정 정치 권한은 현재 크리스토퍼 룩슨 총리가 이끄는 정부에 의해 행사됩니다. 찰스 3세는 이 나라의 왕이고 총독 신디 키로가 대표합니다. 또한 뉴질랜드는 지방 정부의 목적을 위해 11개의 지방 의회와 67개의 영토 당국으로 구성되어 있습니다. 뉴질랜드의 영토는 또한 토켈라우(종속 영토), 쿡 제도와 니우에(뉴질랜드와 자유롭게 연합한 자치주), 그리고 남극에 대한 뉴질랜드의 영유권인 로스 의존도를 포함합니다.

뉴질랜드는 유엔, 영연방, ANZUS, UKUSA, OECD, ASEAN Plus Six, 아시아 태평양 경제 협력체, 태평양 공동체 및 태평양 제도 포럼의 회원국입니다. 미국과 특히 긴밀한 관계를 유지하고 있으며, 주요 비NATO 동맹국 [15]중 하나인 영국과 호주와 함께 양국 간 "트랜스 태즈먼" 정체성을 공유하고 있습니다.[16]

어원

뉴질랜드를 방문한 최초의 유럽 방문객인 네덜란드 탐험가 아벨 태즈먼(Abel Tasman)은 이 섬들이 제이콥 르 메이어(Jacob Le Maire)가 남아메리카 남단에서 목격한 스태튼 랜드의 일부라고 믿고 스태튼 랜드(Staten Land)라는 이름을 붙였습니다.[17][18] 헨드릭 브라우어는 1643년에 남미 땅이 작은 섬이라는 것을 증명했고, 네덜란드 지도 제작자들은 그 후 태즈먼의 발견물을 네덜란드의 질랜드 지방의 이름을 따서 라틴어에서 Nova Zeelandia로 이름을 바꿨습니다.[17][19] 이 이름은 나중에 뉴질랜드로 영어화되었습니다.[20][21]

이것은 마오리어로 누 티레니(Te Tiritio Waitangi의 철자 Nu Tirani)라고 썼습니다. 1834년 마오리어로 작성된 "그 와카푸탕가 오트 랑가티라탕가 오 누 티레니"라는 제목의 문서가 영어로 번역되어 뉴질랜드 독립선언문이 되었습니다. 뉴질랜드 연합 부족인 응가 하푸 누 티레니의 응가 랑가티라탕가에서 테 W(h)akaminenga가 준비한 것으로, 이미 뉴질랜드 연합 부족의 국기를 인정하고 글레넬그 경의 편지에서 선언을 인정한 왕 윌리엄 4세에게 사본이 보내졌습니다.[22][23]

Aotearoa (pronounced [aɔˈtɛaɾɔa] in Māori and /ˌaʊtɛəˈroʊ.ə/ 영어로는 '긴 흰 구름의 땅'으로 번역되기도 합니다.)는 현재 뉴질랜드의 마오리족 이름입니다. 유럽인들이 오기 전에 마오리가 나라 전체의 이름을 지었는지는 알 수 없습니다; 아오테아로아는 원래 단지 북섬만을 가리켰습니다.[25] 마오리 섬에는 북섬을 뜻하는 테 이카아마우이(Te Ika-a-Maui)와 남섬을 뜻하는 테 와이포우나무(Te Waipouamu), 남섬을 뜻하는 테 와카오 아오라키(Te Wakao Aoraki) 등의 전통적인 이름이 있었습니다.[26] 초기 유럽 지도들은 이 섬들을 북쪽(북섬), 중간(남섬), 그리고 남쪽(스튜어트섬/라키우라)이라고 이름 붙였습니다.[27] 1830년, 지도 제작자들은 두 개의 가장 큰 섬들을 구별하기 위해 지도에 "북"과 "남"을 사용하기 시작했고, 1907년에는 이것이 받아들여진 규범이었습니다.[21] 뉴질랜드 지리 위원회는 2009년에 북섬과 남섬의 이름이 공식화된 적이 없으며 2013년에 이름과 대체 이름이 공식화되었다는 것을 발견했습니다. 이것은 북섬 또는 테 이카아마우이, 남섬 또는 테 와이포나무로 이름을 정했습니다.[28] 각 섬에 대해 영어 또는 마오리 이름을 사용하거나 둘 다 함께 사용할 수 있습니다.[28] 마찬가지로 마오리어와 영어 이름이 함께 사용되기도 합니다(Aotearoa New Zealand).[29][30] 그러나 이것은 공식적인 인정이 없습니다.[31]

채텀 제도의 토착어인 모리오리어에서 아오테와 아오테아라는 단어는 뉴질랜드 본토를 가리키는 것으로 생각되는 용어입니다.[32][33]

역사

뉴질랜드는 인간이 마지막으로 정착한 주요 육지였습니다. 대부분의 마오리족이 인정한 뉴질랜드 군도에 인류 최초로 발을 디딘 쿠페의 이야기는 역사학자들에게 신빙성이 있다고 여겨지는데, 쿠페는 일반적으로 역사적으로 존재했다고 여겨집니다.[37] 대부분의 역사는 이것이 대략 40세대 전(서기 900년에서 1200년 사이)에 일어났다고 주장합니다.[38] 쿠페의 반전설적인 여정과 마오리족의 이주에 대한 보다 구체적인 이유가 다투어지고 있습니다. 일부 역사학자들은 당시 하와이키를 비롯한 폴리네시아 섬들이 상당한 내부 갈등을 겪고 있었고, 이로 인해 이 섬들에서 이탈한 것으로 보고 있습니다. 일부 역사학자들은 이것이 전 세계적으로 농작물 황폐화를 일으켰고 아마도 소빙하기를 촉발시키는 데 도움을 주었던 1257년의 Samalas 화산 폭발의 여파 때문이라고 주장합니다.[39][40]

방사성 탄소 연대 측정, 마오리족 내의 산림전용 및 미토콘드리아 DNA 변이성에 대한 증거는 동 폴리네시아인들이 1250년에서 1300년 사이에 뉴질랜드 군도에 처음 정착했음을 시사하지만, 새로운 고고학 및 유전학 연구는 1280년 이전의 것을 가리키고 있습니다. 적어도 1320년에서 1350년 사이의 주요 정착기를 가지고 [44][45]계보 전통에 근거한 증거와 일치합니다.[46][47] 이것은 태평양 섬들을 통과하는 긴 연속 항해의 정점을 나타냈습니다.[48] 동부 폴리네시아인들에 의한 뉴질랜드의 정착은 계획적이고 계획적이었다는 것이 역사가들의 광범위한 공감대입니다.[49] 그 후 몇 세기 동안 폴리네시아 정착민들은 현재 마오리로 알려진 독특한 문화를 발전시켰습니다. 인구는 서로 다른 iwi (부족)과 hapu (부족)을 형성하여 때로는 협력하고 때로는 경쟁하고 때로는 서로 싸웠습니다.[50] 어느 시점에 마오리족이 현재 차탐 제도로 알려진 ē 코후로 이주하여 그들의 독특한 모리오리 문화를 발전시켰습니다. 모리오리 개체군은 1835년에서 1862년 사이에 모리오리 집단 학살로 거의 전멸했는데, 이는 1830년대에 타라나키 마오리의 침략과 노예화 때문이었지만 유럽의 질병도 원인이 되었습니다. 1862년에 101마리만 살아남았고, 마지막으로 알려진 혼혈 모리오리는 1933년에 사망했습니다.[53]

1642년 네덜란드 탐험가 아벨 태즈먼과 은가티 투마타코키리의 적대적인 조우에서 [54][55]태즈먼의 선원 4명이 사망하고, 적어도 1명의 마오리가 캐니스터 총에 맞았습니다.[56] 유럽인들은 1769년까지 뉴질랜드를 다시 방문하지 않았는데, 그때 영국의 탐험가 제임스 쿡이 거의 모든 해안선을 지도로 만들었습니다.[55] 쿡에 이어 뉴질랜드에는 수많은 유럽과 북미 포경선, 봉인선, 무역선이 방문했습니다. 그들은 유럽의 음식, 금속 도구, 무기 및 기타 상품을 목재, 마오리 음식, 공예품 및 물과 교환했습니다.[57] 감자와 머스킷의 도입은 마오리 농업과 전쟁을 변화시켰습니다. 감자는 신뢰할 수 있는 식량 잉여를 제공하여 더 길고 지속적인 군사 작전을 가능하게 했습니다.[58] 1801년에서 1840년 사이에 벌어진 600여 개의 전투에서 3만-4만 명의 마오리족이 사망했습니다.[59] 19세기 초부터 기독교 선교사들은 뉴질랜드에 정착하기 시작했고, 결국 마오리족의 대부분을 개종시켰습니다.[60] 마오리족은 19세기 동안 접촉 전 수준의 약 40%로 감소했으며, 질병이 유입된 것이 주요 요인이었습니다.[61]

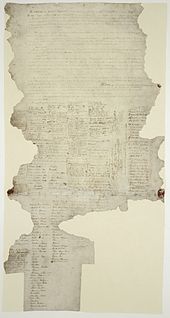

1832년 영국 정부는 제임스 버스비를 뉴질랜드 주재 영국인으로 임명했습니다.[62] 그의 임무는 시드니 주지사인 부르크가 그에게 부여한 것으로, "좋은 지위에 있는" 정착민들과 무역상들을 보호하고, 마오리에 대한 "분노"를 방지하고, 탈출한 죄수들을 체포하는 것이었습니다.[62][63] 1835년 샤를 드 티에리에 의해 프랑스의 정착이 임박했다는 발표가 있은 후, 애매모호한 뉴질랜드 연합 부족들은 영국의 윌리엄 4세에게 보호를 요청하는 독립선언문을 보냈습니다.[62] 계속되는 불안, 뉴질랜드 회사가 제안한 뉴질랜드의 정착과 독립 선언의 의심스러운 법적 지위는 식민지 사무소가 영국의 영유권을 주장하기 위해 윌리엄 홉슨 선장을 파견하고 마오리족과 조약을 협상하도록 유도했습니다.[64] 와이탕기 조약은 1840년 2월 6일에 섬만에서 처음으로 체결되었습니다.[65] 1840년 5월 21일, 뉴질랜드 회사가 웰링턴에 독립적인 정착촌을 세우려는 시도에 대한 응답으로,[66][67] 마오리가 서명할 조약의 사본이 아직 전국에 유포되고 있었음에도 불구하고 홉슨은 뉴질랜드 전체에 대한 영국의 주권을 선언했습니다.[68] 조약이 체결되고 주권이 선포되면서 특히 영국에서 온 이민자들이 증가하기 시작했습니다.[69]

뉴질랜드는 1841년 5월 3일에 별도의 크라운 식민지인 뉴질랜드 식민지가 될 때까지 뉴사우스웨일스 식민지의 종속국으로 관리되었습니다.[70][71] 1843년 식민지 정부와 마오리 사이에 토지와 영유권을 둘러싼 분쟁으로 무장 충돌이 시작되었습니다. 이러한 분쟁은 주로 북섬에서 수천 명의 제국 군대와 영국 해군이 뉴질랜드로 오게 되었고 뉴질랜드 전쟁으로 알려지게 되었습니다. 이러한 무력 충돌 이후, 정착민들의 요구에 부응하기 위해 마오리족의 넓은 지역이 정부에 의해 몰수되었습니다.[72]

식민지는 1852년에 대표 정부를 얻었고, 1854년에 첫 번째 의회가 열렸습니다.[73] 1856년 식민지는 실질적으로 자치권을 갖게 되었고, 1860년대 중반에 부여된 토착 정책을 제외하고 모든 국내 문제에 대한 책임을 갖게 되었습니다.[73] 남섬이 별도의 식민지를 형성할 수도 있다는 우려가 있은 후, 알프레드 도멧 총리는 수도를 오클랜드에서 쿡 해협 근처의 지역으로 이전하는 결의안을 옮겼습니다.[74][75] 웰링턴은 1865년 의회가 처음으로 공식적으로 그곳에 앉으면서 중심지로 선정되었습니다.[76]

1886년, 뉴질랜드는 오클랜드 북동쪽 약 1,000 km (620 mi)에 있는 화산 케르마데크 제도를 합병했습니다. 1937년 이후, 이 섬들은 라울 섬 역에 있는 약 6명의 사람들을 제외하고는 무인도입니다. 이 섬들은 뉴질랜드의 북쪽 국경을 남위 29도에 두고 있습니다.[77] 1982년 UNCLOS 이후, 이 섬들은 뉴질랜드의 배타적 경제수역에 상당한 기여를 했습니다.[78]

1891년 자유당은 최초의 조직적인 정당으로 집권했습니다.[79] 집권 기간의 대부분을 리처드 세든이 이끄는 자유당 정부는 많은 중요한 사회적, 경제적 조치들을 통과시켰습니다.[80] 1893년 뉴질랜드는 모든 여성에게 투표권을[79] 부여한 세계 최초의 국가였으며 1894년 고용주와 노조 간의 강제 중재 채택을 개척했습니다.[81] 자유당은 또한 1894년 세계 최초로 최저임금을 보장했습니다.[82]

1907년 뉴질랜드 의회의 요청에 따라 에드워드 7세는 뉴질랜드의 자치적 지위를 [83]반영하여 대영제국 내의 자치령을 선포했습니다.[84] 1947년, 뉴질랜드는 웨스트민스터 법령을 채택하여 영국 의회가 동의 없이는 더 이상 국가를 위해 입법할 수 없음을 확인했습니다. 영국 정부의 잔여 입법권은 이후 1986년 헌법법에 의해 삭제되었고, 영국 법원에 대한 최종 항소권은 2003년에 폐지되었습니다.[73]

20세기 초, 뉴질랜드는 제 1, 2차 세계 대전에서[85] 싸웠고 대공황을 겪으며 세계 문제에 관여했습니다.[86] 경기 침체는 제1차 노동당 정부의 선출과 포괄적 복지국가와 보호주의 경제의 확립으로 이어졌습니다.[87] 뉴질랜드는 제2차 세계 대전 이후 번영을 누렸고,[88] 마오리는 전통적인 농촌 생활을 떠나 일자리를 찾아 도시로 이주하기 시작했습니다.[89] 유럽중심주의를 비판하고 마오리 문화와 와이탕기 조약에 대한 더 큰 인정을 위해 노력한 마오리 시위 운동이 전개되었습니다.[90] 1975년에는 조약 위반 혐의를 조사하기 위한 와이탕기 재판소가 설립되었고, 1985년에는 역사적인 불만을 조사할 수 있게 되었습니다.[65] 정부는 이러한 불만을 해결하기 위해 많은 iwi와 협상을 벌였지만,[91] 마오리는 2000년대에 해안과 해저에 대한 주장이 논란이 된 것으로 판명되었습니다.[92][93]

정부와 정치

뉴질랜드는 헌법이 성문화되어 있지는 않지만,[94] 의회 민주주의를 가진 입헌 군주국입니다.[95] 찰스 3세는 뉴질랜드의[96] 왕이고 따라서 국가 원수입니다.[97] 국왕은 총독이 대표하며, 그는 총리의 조언에 따라 임명합니다.[98] 총독은 부정의 사례를 검토하고 장관, 대사 및 기타 주요 공무원을 임명하는 등의 왕실의 특권을 행사할 수 있으며,[99] 드물게 예비 권한(예: 의회를 해산하거나 법안의 왕실 승인을 법률로 거부할 수 있는 권한)을 행사할 수 있습니다.[100] 군주와 총독의 권한은 헌법적 제약에 의해 제한되며, 장관의 자문 없이는 정상적으로 행사할 수 없습니다.[100]

뉴질랜드 의회는 입법권을 가지고 있으며 왕과 하원으로 구성되어 있습니다.[101] 1950년에 이것이 폐지될 때까지 참의원인 입법회도 포함되었습니다.[101] 왕권과 다른 정부 기관에 대한 의회의 우월성은 1689년 권리장전에 의해 영국에서 확립되었고 뉴질랜드에서 법으로 비준되었습니다.[101] 하원은 민주적으로 선출되며, 과반 의석을 가진 정당이나 연립정부로 정부가 구성됩니다. 다수결이 형성되지 않으면 신임투표와 공급투표에서 다른 정당의 지지가 확실해지면 소수정부가 구성될 수 있습니다.[101] 총독은 관례에 따라 여당 또는 연합의 의회 지도자인 총리의 조언에 따라 장관을 임명합니다.[102] 각료들이 구성하고 총리가 이끄는 내각은 정부의 가장 높은 정책 결정 기관이며 정부의 중요한 행동을 결정하는 책임이 있습니다.[103] 내각 구성원들은 주요 결정을 집단적으로 내리므로 이러한 결정의 결과에 대해 집단적으로 책임을 집니다.[104] 2023년 11월 27일부터 제42대, 현재 총리는 크리스토퍼 룩슨입니다.[105]

국회의원 총선거는 지난 선거 후 늦어도 3년 이내에 치러져야 합니다.[106] 1853년에서 1993년 사이의 거의 모든 총선은 선후 투표제로 치러졌습니다.[107] 1996년 선거 때부터 혼합형 비례대표제(MMP)라는 비례대표제가 사용되고 있습니다.[95] MMP 제도 하에서, 한 명당 두 표가 있는데, 한 표는 유권자의 선거인단에 서 있는 후보를 위한 것이고, 다른 한 표는 정당을 위한 것입니다. 2018년 인구조사 자료에 따르면 72명의 선거인단(마오리만 선택적으로 투표할 수 있는 7명의 마오리 선거인단 포함)이 있으며,[108] 120석 중 나머지 48석은 의회의 대표성이 정당 투표를 반영하도록 배정되어 있습니다. 정당이 의석에 적합하기 전에 적어도 한 명의 유권자 또는 전체 정당 투표의 5%를 얻어야 한다는 임계치.[109] 1930년대 이후의 선거는 국민당과 노동당이라는 두 정당이 지배해 왔습니다. MMP가 도입된 이후로 더 많은 정당들이 의회에 대표로 참여하고 있습니다.[110]

대법원장이 이끄는 뉴질랜드의 사법부에는 대법원, 항소법원, 고등법원, 하급법원 등이 있습니다.[111][112] 법관과 사법관은 사법의 독립성 유지를 돕기 위해 임기와 관련하여 비정치적이고 엄격한 규칙에 따라 임명됩니다.[95] 이는 이론적으로 사법부가 자신들의 결정에 다른 영향을 미치지 않고 의회가 제정한 법률만을 근거로 법을 해석할 수 있도록 허용합니다.[113]

뉴질랜드는 세계에서 가장 안정적이고 잘 통치되고 있는 주 중 하나로 알려져 있습니다.[114] 2017년 기준,[update] 이 나라는 민주적인 기관들의 힘에서 4위를 차지했고,[115] 정부 투명성과 부패 부족에서 1위를 차지했습니다.[116] 이 나라의 LGBT 권리는 오세아니아에서 가장 관대한 권리 중 하나로 인식되고 있습니다.[117] 뉴질랜드는 최근 총선 투표율이 82%로 OECD 평균 69%[118]에 비해 정치 과정에 대한 시민 참여도가 높은 것으로 나타났습니다. 그러나 지방의회 선거의 경우에는 그렇지 않습니다. 2019년의 이미 낮은 42%의 투표율에 비해 2022년 지방 선거에서는 역사적으로 낮은 36%의 뉴질랜드인이 투표했습니다.[119][120][121] 미국 국무부의 2017년 인권 보고서는 뉴질랜드 정부가 일반적으로 개인의 권리를 존중하지만 마오리족의 사회적 지위에 대해 우려를 표명했다고 언급했습니다.[122] 구조적 차별과 관련하여 뉴질랜드 인권위원회는 그것이 현실적이고 지속적인 사회경제적 문제라는 강력하고 일관된 증거가 있다고 주장했습니다.[123] 뉴질랜드의 구조적 불평등의 한 예는 형사사법제도에서 볼 수 있습니다. 법무부에 따르면 마오리족은 범죄로 유죄 판결을 받은 뉴질랜드인의 45%와 수감자의 53%로 과도하게 대표되는 반면 인구의 16.5%에 불과합니다.[124][125]

대외관계 및 군사

뉴질랜드 식민지 기간 동안 영국은 대외 무역과 대외 관계를 책임졌습니다.[126] 1923년과 1926년 제국회의는 뉴질랜드가 독자적인 정치 조약을 협상할 수 있도록 허용해야 한다고 결정했고, 1928년 일본과 최초의 상업 조약이 비준되었습니다. 1939년 9월 3일, 뉴질랜드는 영국과 동맹을 맺고 독일에 전쟁을 선포했습니다. "그녀가 가는 곳, 우리가 가는 곳, 그녀가 서 있는 곳, 우리가 서 있는 곳."[127]

1951년, 영국은 유럽의 이익에 점점 더 집중하게 [128]되었고 뉴질랜드는 호주와 미국과 함께 ANZUS 안보 조약에 가입했습니다.[129] 베트남 전쟁 시위,[130] 레인보우 워리어 침몰 이후 미국의 프랑스 훈계 거부,[131] 환경 및 농산물 무역 문제에 대한 이견, 뉴질랜드의 핵 없는 정책 등으로 뉴질랜드에 대한 미국의 영향력은 약화되었습니다.[132][133] 미국이 ANZUS의 의무를 중단했음에도 불구하고, 이 조약은 유사한 역사적 흐름을 따라온 뉴질랜드와 호주 사이에서 여전히 유효했습니다.[134] 양국 간에 긴밀한 정치적 접촉이 유지되고 있으며, 자유 무역 협정과 시민들이 제한 없이 양국을 방문하고 생활하며 일할 수 있는 여행 협정이 체결되어 있습니다.[135] 2013년[update] 호주에는 약 650,000명의 뉴질랜드 시민이 살고 있는데, 이는 뉴질랜드 인구의 15%에 해당합니다.[136]

뉴질랜드는 태평양 섬나라 중에서도 강한 존재감을 가지고 있습니다.[137] 뉴질랜드 원조의 상당 부분이 이들 국가로 가고, 많은 태평양 사람들이 취업을 위해 뉴질랜드로 이주합니다.[138] 영구 이주는 1970년 사모아 쿼터 제도와 2002년 태평양 접근 범주에 따라 규제되며, 이 제도는 매년 사모아 국민 최대 1,100명과 그 밖의 태평양 섬 주민 최대 750명이 뉴질랜드 영주권자가 될 수 있도록 허용합니다. 2007년에는 임시 이주를 위한 계절 근로자 제도가 도입되었고, 2009년에는 약 8,000명의 태평양 섬 주민이 그 아래에서 고용되었습니다.[139] 뉴질랜드는 태평양 제도 포럼, 태평양 공동체, 아시아 태평양 경제 협력, 동남아시아 국가 연합 지역 포럼(동아시아 정상회의 포함)에 참여하고 있습니다.[135] 뉴질랜드는 아시아 태평양 지역의 중견국이자 [140]신흥 강대국으로 묘사되어 왔습니다.[141][142] 이 나라는 유엔,[143] 영연방[144] 및 경제협력개발기구(OECD)의 회원국이며 [145]5대 전력 방위 협정에 참여하고 있습니다.[146]

뉴질랜드의 군사 서비스인 국방군은 뉴질랜드 육군, 뉴질랜드 왕립 공군, 뉴질랜드 왕립 해군으로 구성되어 있습니다.[147] 뉴질랜드의 국방 수요는 직접적인 공격 가능성이 희박하기 때문에 완만합니다.[148] 그러나 군은 세계적으로 존재하고 있습니다. 이 나라는 갈리폴리, 크레타,[149] 엘 알라메인,[150] 카시노에서 주목할 만한 캠페인을 벌이며 두 세계 대전에 모두 참전했습니다.[151] 갈리폴리 캠페인은 뉴질랜드의 국가 정체성을[152][153] 키우는 데 중요한 역할을 했고 호주와 공유하는 ANZAC 전통을 강화했습니다.[154]

베트남과 두 차례의 세계대전 외에도 뉴질랜드는 제2차 보어 전쟁,[155] 한국 전쟁,[156] 말레이 비상사태,[157] 걸프 전쟁, 아프가니스탄 전쟁 등에 참전했습니다. 키프로스, 소말리아, 보스니아 헤르체고비나, 시나이, 앙골라, 캄보디아, 이란-이라크 국경, 부건빌, 동티모르, 솔로몬 제도 등 여러 지역 및 세계 평화 유지 임무에 기여했습니다.[158]

오늘날 뉴질랜드는 미국과 특히 긴밀한 관계를 누리고 있으며,[15] 호주뿐만 아니라 주요 비 NATO 동맹국 중 하나이며, 후자의 시민들 사이에 "트랜스 태즈먼" 정체성이 일반적입니다.[16] 뉴질랜드는 공식적으로 UKUSA 협정으로 알려진 Five Eyes 정보 공유 협정의 회원국입니다. 이 협정의 5개 회원국은 핵심적인 영해권을 타협합니다. 호주, 캐나다, 뉴질랜드, 영국, 미국.[159] 2012년부터 뉴질랜드는 NATO와 파트너십 상호운용성 이니셔티브(Partnership Interoperability Initiative)에 따라 파트너십 계약을 체결하고 있습니다.[160][161][162]

지방자치단체 및 대외 영토

초기 유럽 정착민들은 뉴질랜드를 지방으로 나누어 어느 정도의 자치권을 가지고 있었습니다.[163] 재정적 압박과 철도, 교육, 토지 판매, 기타 정책을 통합하려는 열망 때문에 정부는 중앙집권화되었고 지방은 1876년에 폐지되었습니다.[164] 지방은 지역 공휴일과[165] 스포츠 경쟁에서 기억됩니다.[166]

1876년부터 여러 의회가 중앙정부가 정한 법률에 따라 지방을 관리해 왔습니다.[163][167] 1989년 정부는 지방정부를 지방의회와 영토 당국의 현재의 2층 구조로 개편했습니다.[168] 1975년에 존재했던 249개 지방[168] 자치 단체는 현재 67개의 지방 자치 단체와 11개의 지방 의회로 통합되었습니다.[169] 지역 의회의 역할은 "특별히 자원 관리에 중점을 둔 자연 환경"을 규제하는 것이고,[168] 영토 당국은 하수, 물, 지방 도로, 건물 동의 및 기타 지역 문제를 담당합니다.[170][171] 영토 의회 중 5개는 단일 기관이며 지역 의회 역할도 합니다.[171] 영토 당국은 13개 시의회, 53개 구의회, 채텀 제도 의회로 구성되어 있습니다. 채텀 제도 이사회는 공식적으로 단일 기관은 아니지만 지역 이사회의 많은 기능을 담당합니다.[172]

15개 영연방 국가 [173]중 하나인 뉴질랜드 왕국은 뉴질랜드의 왕이나 여왕이 주권을 가지고 있는 전체 지역이며 뉴질랜드, 토켈라우, 로스 종속국, 쿡 제도, 니우에로 구성되어 있습니다.[94] 쿡 제도(Cook Islands)와 니우에(Niue)는 뉴질랜드와 자유롭게 연합한 자치주입니다.[174][175] 뉴질랜드 의회는 이들 국가를 위한 법안을 통과시킬 수 없지만, 그들의 동의가 있으면 외교 및 국방 분야에서 그들을 대신할 수 있습니다. 토켈라우는 자치령이 아닌 지역으로 분류되지만, 3명의 원로들로 구성된 의회(토켈라우 환초마다 1명씩)에 의해 관리됩니다.[176] 로스 의존 관계는 스콧 기지 연구 시설을 운영하는 뉴질랜드의 남극 지역 영유권 주장입니다.[177] 뉴질랜드 국적법은 영토의 모든 부분을 동등하게 취급하기 때문에 뉴질랜드, 쿡 제도, 니우에, 토켈라우, 로스 의존에서 태어난 대부분의 사람들은 뉴질랜드 시민입니다.[178][n 8]

지리 및 환경

뉴질랜드는 물 반구의 중심 근처에 위치하고 있으며 두 개의 주요 섬과 700개 이상의 작은 섬으로 구성되어 있습니다.[180] 두 개의 주요 섬(북섬 또는 테 이카아마우이, 남섬 또는 테 와이포우나무)은 쿡 해협에 의해 분리되며, 가장 좁은 지점에서 폭이 22 킬로미터(14 마일)입니다.[181] 북섬과 남섬 이외에 사람이 사는 가장 큰 다섯 개의 섬은 스튜어트 섬(포보 해협 건너), 채텀 섬, 그레이트 배리어 섬(하우라키 만),[182] 더빌 섬(말버러 사운드),[183] 와이헤크 섬(오클랜드 중부에서 약 22km(14m) 떨어진 곳에 있습니다.[184]

뉴질랜드는 동서축을 따라 1,600킬로미터가 넘는 좁고 최대 폭은 400킬로미터입니다.[185] 해안선의[186] 길이는 약 15,000킬로미터(9,300마일)이고 총 육지 면적은 268,000제곱킬로미터(103,500제곱마일)입니다.[187] 멀리 떨어진 섬들과 긴 해안선 때문에 이 나라는 광범위한 해양 자원을 보유하고 있습니다. 배타적 경제수역은 국토 면적의 15배 이상을 차지하는 세계에서 가장 큰 지역 중 하나입니다.[188]

남섬은 뉴질랜드에서 가장 큰 육지입니다. 이것은 남알프스 산맥에 의해 길이를 따라 나뉩니다.[189] 3,000미터(9,800피트)가 넘는 18개의 봉우리가 있으며, 그 중 가장 높은 곳은 3,724미터(12,218피트)의 아오라키/마운트 쿡(Aoraki/Mount Cook)입니다.[190] 피오르드랜드의 가파른 산과 깊은 피오르드는 남섬 남서부 구석의 광범위한 빙하기를 기록하고 있습니다.[191] 북섬은 산이 적지만 화산 활동으로 특징지어집니다.[192] 활동이 활발한 타우포 화산지대는 북섬에서 가장 높은 산인 루아페후 산(2,797미터(9,177피트)에 의해 점입된 거대한 화산 고원을 형성했습니다. 이 고원에는 또한 세계에서 가장 활동적인 초화산 중 하나인 칼데라에 자리잡고 있는 [180]타우포 호수가 위치하고 있습니다.[193] 뉴질랜드는 지진과 화산 폭발이 일어나기 쉽습니다.

이 나라는 태평양과 인도-오스트레일리아판 사이에 걸쳐 있는 역동적인 경계 때문에 다양한 지형, 그리고 아마도 파도 위에 나타날지도 모릅니다.[194] 뉴질랜드는 곤드와난 초대륙에서 분리된 후 점차 물에 잠기는 호주 크기의 거의 절반에 가까운 미대륙인 질란디아의 일부입니다.[195][196] 약 2,500만 년 전, 판 구조 운동의 변화가 이 지역을 뒤틀고 구겨지기 시작했습니다. 이는 현재 알파인 단층 옆의 지각이 압축되어 형성된 남부 알프스에서 가장 뚜렷하게 나타납니다. 다른 곳에서는 판 경계가 하나의 판 아래에 섭입되어 남쪽으로 푸이세구르 해구, 북섬 동쪽의 히쿠란기 해구, 북쪽으로 케르마데크 해구와 통가 해구를[197] 생성합니다.[194]

뉴질랜드는 호주와 함께 오스트랄라시아라고 알려진 지역의 일부입니다.[198] 또한 폴리네시아라고 불리는 지리적, 민족적 지역의 남서쪽 끝을 형성합니다.[199] 오세아니아는 7대륙 모델에 포함되지 않은 호주 대륙과 뉴질랜드, 태평양의 다양한 섬나라들을 아우르는 더 넓은 지역입니다.[200]

기후.

뉴질랜드의 기후는 주로 온화한 해양성 기후이며, 연평균 기온은 남쪽이 10°C(50°F)에서 북쪽이 16°C(61°F)입니다.[201] 역사적 최대치와 최소치는 캔터베리주 랑지오라에서 42.4 °C (108.32 °F), 오타고주 랑푸르에서 -25.6 °C (-14.08 °F)입니다.[202] 조건은 남섬 서해안의 극도로 습윤한 지역부터 중부 오타고의 반건조 지역, 캔터베리 내륙과 노스랜드의 매켄지 분지까지 지역에 따라 급격하게 다릅니다.[203][204] 7대 도시 중 가장 건조한 곳은 크라이스트처치로 1년에 평균 618 밀리미터(24.3 인치)의 비가 내렸고 웰링턴은 그 두 배 가까이 비가 내렸습니다.[205] 오클랜드, 웰링턴, 크라이스트처치는 모두 연간 평균 2,000시간 이상의 햇빛을 받습니다. 남섬의 남쪽과 남서쪽은 더 시원하고 구름이 많은 기후로 약 1,400-1,600시간 정도가 소요됩니다. 남섬의 북쪽과 북동쪽은 이 나라에서 가장 햇볕이 잘 드는 지역이고 약 2,400-2,500시간 정도가 소요됩니다.[206] 일반적인 눈 시즌은 6월 초부터 10월 초까지이지만, 이번 시즌에는 바깥에서 한랭 스냅이 발생할 수 있습니다.[207] 눈은 남섬의 동쪽과 남쪽 그리고 전국의 산지에서 흔히 볼 수 있습니다.[201]

| 위치 | 1월고 °C(°F) | 1월 저점 °C(°F) | 7월고 °C(°F) | 7월 저점 °C(°F) | 연간강우량 mm(인치) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 오클랜드 | 23 (73) | 15 (59) | 15 (59) | 8 (46) | 1,212 (47.7) |

| 웰링턴 | 20 (68) | 14 (57) | 11 (52) | 6 (43) | 1,207 (47.5) |

| 호키티카 | 20 (68) | 12 (54) | 12 (54) | 3 (37) | 2,901 (114.2) |

| 크라이스트처치 | 23 (73) | 12 (54) | 11 (52) | 2 (36) | 618 (24.3) |

| 알렉산드라 | 25 (77) | 11 (52) | 8 (46) | −2 (28) | 359 (14.1) |

생물다양성

8천만 년[209] 동안 뉴질랜드의 지리적 고립과 섬 생물지리학은 뉴질랜드의 동물, 곰팡이 및 식물 종의 진화에 영향을 미쳤습니다. 물리적 고립은 생물학적 고립을 야기했고, 그 결과 독특한 식물과 동물의 예와 광범위한 종의 개체군을 가진 역동적인 진화 생태학을 낳았습니다.[210][211] 뉴질랜드의 동식물은 원래 곤드와나에서 뉴질랜드가 조각난 것에서 유래한 것으로 여겨졌지만, 최근의 증거는 종들이 분산된 것으로 추정합니다.[212] 뉴질랜드 토착 관속 식물의 약 82%가 고유종으로 65개 속에 걸쳐 1,944종을 커버하고 있습니다.[213][214] 지의 형성 종을 포함하여 뉴질랜드에서 기록된 균류의 수는 알려져 있지 않으며 고유한 균류의 비율도 알려져 있지 않지만, 추정에 따르면 뉴질랜드에는[213] 약 2,300 종의 지의 형성 균류가 있으며 이 중 40%가 고유합니다.[215] 두 가지 주요 유형의 숲은 발아한 포도나무가 있는 활엽수가 지배하거나 더 차가운 기후의 남부 너도밤나무가 지배하는 숲입니다.[216] 나머지 식생 유형은 초지로 구성되어 있으며, 대부분은 투스톡(tussock)입니다.[217]

인간이 도착하기 전에는 땅의 약 80%가 숲으로 덮여 있었고, 나무가 없는 고산, 습윤, 불임, 화산 지역만 있었습니다.[218] 인간이 도착한 후 대규모 산림전용이 발생했는데, 폴리네시아 정착 후 산림 덮개의 절반 정도가 화재로 소실되었습니다. 나머지 숲의 대부분은 유럽 정착 후에 떨어졌으며, 목축 농업을 위한 공간을 마련하기 위해 벌목되거나 개간되어 숲이 땅의 23%만 차지하고 있습니다.[220]

숲은 새들에 의해 지배되었고, 포유류 포식자의 부족은 키위, 카카포, 웨카, 타카 ē와 같은 일부 동물들로 하여금 날지 못하게 진화하게 만들었습니다. 인간의 도래, 서식지의 변화, 그리고 쥐, 흰 족제비와 다른 포유류의 도입은 모아와 하스트 독수리와 같은 큰 새들을 포함한 많은 새 종들의 멸종을 가져왔습니다.[222][223]

다른 토착 동물들은 파충류(투아타라, 피부와 도마뱀붙이), 보호 멸종 위기에 처한 해밀턴 개구리, 거미, 곤충(ē타), 달팽이 등으로 대표됩니다. 투아타라(tuatara)와 같은 일부는 매우 독특하여 살아있는 화석이라고 불립니다.[228] 2006년 적어도 1600만년 된 독특한 쥐 크기의 육지 포유동물의 뼈가 발견되기 전까지 세 종의 박쥐가 뉴질랜드에서 유일한 토종 육지 포유동물의 징후였습니다.[229][230] 그러나 해양 포유류는 풍부하여 전 세계 고래류(고래, 돌고래, 돌고래)의 거의 절반과 뉴질랜드 해역에 많은 수의 물개가 보고되었습니다.[231] 많은 바닷새들이 뉴질랜드에서 번식하는데, 그 중 3분의 1이 뉴질랜드 특유의 품종입니다.[232] 뉴질랜드에는 세계 18종의 펭귄 중 13종이 있어 다른 어느 나라보다 더 많은 펭귄 종이 발견되고 있습니다.[233]

인간이 도착한 이래로, 적어도 51마리의 새, 3마리의 개구리, 3마리의 도마뱀, 1마리의 민물고기, 그리고 1마리의 박쥐를 포함하여, 이 나라의 척추동물 종의 거의 절반이 멸종되었습니다. 다른 사람들은 멸종 위기에 처했거나 범위가 심각하게 줄어들었습니다.[222] 하지만, 뉴질랜드의 환경 보호론자들은 섬 보호구역, 해충 구제, 야생동물 이동, 섬과 다른 보호구역의 육성 및 생태 복원을 포함하여, 위협을 받고 있는 야생동물의 회복을 돕기 위한 여러 방법들을 개척해왔습니다.[234][235][236][237]

경제.

뉴질랜드는 2021년[update] 인간 개발 지수 13위,[238][12] 2022년[update] 경제 자유 지수 4위로 선진 시장 경제를 가지고 있습니다.[239] 1인당 명목 국내총생산(GDP)이 미화 36,254달러인 고소득 경제입니다.[240] 이 통화는 뉴질랜드 달러로 비공식적으로는 "키위 달러"로 알려져 있으며 쿡 제도(쿡 제도 달러 참조), 니우에, 토켈라우, 핏케언 제도에서도 유통됩니다.[241]

역사적으로, 추출 산업은 봉인, 포경, 아마, 금, 카우리 껌 및 토종 목재에 다른 시기에 집중하면서 뉴질랜드 경제에 강력하게 기여했습니다.[242] 1882년 더니든호에 냉장육이 처음 선적되면서 영국으로의 육류 및 유제품 수출이 이루어졌고, 이는 뉴질랜드의 강력한 경제 성장의 기초가 되었습니다.[243] 영국과 미국의 농산물에 대한 높은 수요는 1950년대와 1960년대에 뉴질랜드 사람들이 호주와 서유럽보다 더 높은 생활 수준을 달성하도록 도왔습니다.[244] 1973년, 영국이 유럽 경제 공동체에[245] 가입하면서 뉴질랜드의 수출 시장은 축소되었고, 1973년 석유 및 1979년 에너지 위기와 같은 다른 복합적인 요인들이 심각한 경제 침체로 이어졌습니다.[246] 뉴질랜드의 생활 수준은 호주와 서유럽의 생활 수준보다 뒤쳐졌고, 1982년까지 뉴질랜드는 세계 은행이 조사한 모든 선진국의 1인당 소득이 가장 낮았습니다.[247] 1980년대 중반 뉴질랜드는 3년에 걸쳐 보조금을 단계적으로 폐지함으로써 농업 부문에 대한 규제를 완화했습니다.[248][249] 1984년 이후 역대 정부들은 주요 거시 경제 구조 조정(처음에는 로게르노믹스, 그 다음에는 루타나시아로 알려짐)에 참여하여 뉴질랜드를 보호주의적이고 고도로 규제된 경제에서 자유화된 자유 무역 경제로 빠르게 전환시켰습니다.[250][251]

실업률은 1987년 주식 시장 붕괴 이후 [253]1991년과 1992년에 10%를 약간 웃도는 정점을 찍었지만, 결국 2007년에 3.7%로 사상 최저치(1986년 이후)로 떨어졌습니다(27개 OECD 국가에서 3위).[253] 하지만 뒤이어 발생한 글로벌 금융위기는 뉴질랜드에 큰 영향을 미쳤는데, GDP가 5분기 연속 감소했고, 30여 년 만에 가장 긴 경기침체를 겪었고,[254][255] 2009년 말 실업률은 7%로 다시 상승했습니다.[256] 다양한 연령대의 실업률은 비슷한 추세를 따르지만 청년층에서 지속적으로 더 높습니다. 2014년 12월 분기 일반 실업률은 5.8% 수준인 반면, 15~21세 청년 실업률은 15.6%[253]였습니다. 뉴질랜드는 1970년대부터[257] 지금도 계속되는 일련의 "뇌 배수"를 겪고 있습니다.[258] 고도로 숙련된 노동자의 거의 4분의 1이 해외에 살고 있는데, 대부분 호주와 영국에 살고 있는데, 이는 선진국 중 가장 큰 비율입니다.[259] 그러나 최근 수십 년 동안 "두뇌 증가"로 인해 유럽과 저개발 국가에서 교육을 받은 전문가들이 유입되었습니다.[260][261] 오늘날 뉴질랜드의 경제는 높은 수준의 혁신으로부터 이익을 얻고 있습니다.[262]

뉴질랜드의 빈곤은 소득 불평등의 증가로 특징지어지는데, 뉴질랜드의 부는 고도로 집중되어 [263]있어 인구의 상위 1%가 국가 부의 16%를 소유하고 있고, 가장 부유한 5%가 38%를 소유하고 있어 국가 수혜자와 연금 수급자를 포함한 인구의 절반이 24,000달러 미만을 받는 극명한 대조를 이룹니다.[264] 게다가 뉴질랜드의 아동 빈곤은 정부에 의해 주요 사회 문제로 확인되었습니다.[265][266] 2022년[update] 6월 기준 중위 균등화 처분 가능 가구 소득의 50% 미만인 저소득 가구에 사는 아동의 12.0%가 있습니다.[267] 빈곤은 소수 민족 가구에서 불균형적으로 높은 영향을 미치며, 2020년[update] 기준 마오리족 아동의 1/4(23.3%)과 태평양 섬 주민 아동의 거의 3/1(28.6%)이 빈곤 상태에서 살고 있습니다.[265]

거래

뉴질랜드는 [268]특히 농산물에서 국제 무역에 크게 의존하고 있습니다.[269] 수출이 생산량의 24%를 차지하고 [186]있어 뉴질랜드는 국제 상품 가격과 세계 경기 둔화에 취약합니다. 2014년 식품은 국가 전체 수출액의 55%를 차지했고, 목재는 두 번째로 많은 수입을 올렸습니다(7%).[270] 2018년[update] 6월 현재 뉴질랜드의 주요 교역국은 중국(27.8bNZ달러), 호주(26.2b달러), 유럽연합(22.9b달러), 미국(17.6b달러), 일본(84b달러)입니다.[271] 2008년 4월 7일, 뉴질랜드와 중국은 선진국과 체결한 첫 번째 그러한 협정인 뉴질랜드-중국 자유 무역 협정에 서명했습니다.[272] 2023년 7월, 뉴질랜드와 유럽 연합은 EU-뉴질랜드 자유 무역 협정을 체결하여 두 지역 간에 거래되는 여러 상품에 대한 관세를 철폐했습니다.[273] 이번 자유무역협정은 기존의 자유무역협정을[274] 확대하고 영향을 받은 산업계의 피드백에 따라 육류와 유제품에[275] 대한 관세가 인하되었습니다.[276]

서비스업이 경제에서 가장 큰 부문이고, 제조업과 건설업, 그리고 농업과 원자재 추출업이 그 뒤를 이었습니다.[186] 관광업은 2016년 뉴질랜드 전체 GDP에 129억 달러(또는 5.6%)를 기여하고 전체 노동력의 7.5%를 지원하는 등 경제에서 중요한 역할을 하고 있습니다.[277] 2017년 해외 방문객 도착은 2022년까지 연평균 5.4%씩 증가할 것으로 예상됩니다.[277]

양모는 19세기 후반 뉴질랜드의 주요 농산물 수출품이었습니다.[242] 1960년대 후반까지도 전체 수출 수입의 3분의 1 이상을 차지했지만,[242] 그 이후로 다른 상품에 비해 가격이 꾸준히 하락하여 [278]더 이상 많은 농부들에게 양모는 수익성이 없습니다.[279] 대조적으로, 낙농업은 1990년과 2007년 사이에 젖소의 수가 두 배로 증가하여 뉴질랜드의 최대 수출 소득자가 되었습니다.[280][281] 2018년 6월까지 유제품은 전체 수출의 17.7%(141억 달러)를 차지했으며,[271] 국내 최대 기업인 폰테라(Fonterra)는 국제 유제품 무역의 거의 3분의 1을 장악하고 있습니다.[282] 2017-18년 기타 수출은 육류(8.8%), 목재 및 목재 제품(6.2%), 과일(3.6%), 기계(2.2%) 및 와인(2.1%)[271]이었습니다. 뉴질랜드의 와인 산업은 낙농업과 비슷한 추세를 따랐는데, 같은 기간 동안 포도밭의 수가 두 배로 [283]증가하여 2007년 처음으로 양모 수출을 추월했습니다.[284][285]

사회 기반 시설

2015년 재생에너지는 뉴질랜드 총 에너지 공급량의 40.1%를 생산했습니다.[286] 이 나라의 전력 공급의 대부분은 수력 발전으로 생산되며, 주요 계획은 와이카토, 와타키 및 클루타 / 마타-아우 강과 마나푸리 강에서 이루어집니다. 지열발전은 또한 중요한 전기 발전기이며, 북섬의 타우포 화산지대에 위치한 여러 개의 큰 발전소가 있습니다. 세대 및 소매 시장의 주요 4개 회사는 컨택 에너지, 제네시스 에너지, 머큐리 에너지 및 메리디안 에너지입니다. 국영 트랜스파워(Transpower)는 남북 섬의 고압 송전망과 두 섬을 연결하는 섬간 HVDC 링크를 운영합니다.[286]

물 공급 및 위생 제공은 일반적으로 품질이 좋습니다. 지역 당국은 대부분의 개발된 지역에 물 추출, 처리 및 분배 인프라를 제공합니다.[287][288]

뉴질랜드의 교통망은 199km(124mi)의 자동차 도로를 포함한 94,000km(58,410mi)의 도로와 [289]4,128km(2,565mi)의 철도 노선으로 구성됩니다.[186] 대부분의 주요 도시와 마을은 버스 서비스로 연결되어 있지만 자가용이 주요 교통 수단입니다.[290] 철도는 1993년에 민영화되었지만 2004년에서 2008년 사이에 정부에 의해 단계적으로 재국유화되었습니다. 국영 기업인 키위 레일은 오클랜드 원 레일과 트랜스데브 웰링턴이 각각 운영하는 오클랜드와 웰링턴의 통근 서비스를 제외하고 현재 철도를 운영하고 있습니다.[291] 철도는 전국적으로 운행되지만, 현재 대부분의 노선은 승객 대신 화물을 운송합니다.[292] 두 주요 섬의 도로 및 철도 네트워크는 웰링턴과 픽톤 사이의 롤온/롤오프 페리로 연결되며, 인터랜더(키위 레일의 일부)와 블루브리지가 운영합니다. 대부분의 해외 방문객은 항공을 통해 도착합니다.[293] 뉴질랜드에는 4개의 국제 공항이 있습니다. 오클랜드, 크라이스트처치, 퀸스타운, 웰링턴; 그러나 오클랜드와 크라이스트처치만이 호주나 피지 이외의 나라로 가는 직항편을 제공합니다.[294]

뉴질랜드 우체국은 1987년 텔레콤 뉴질랜드가 설립될 때까지 뉴질랜드에서 통신에 대한 독점권을 가지고 있었는데, 처음에는 국영 기업으로 운영되었다가 1990년에 민영화되었습니다.[295] 2011년 텔레콤(현 스파크)에서 분리된 코러스는 [296]여전히 통신 인프라의 대부분을 소유하고 있지만, 다른 사업자들과의 경쟁이 치열해졌습니다.[295] 초고속 광대역(Ultra-Fast Broadband)이라는 브랜드로 기가비트가 가능한 파이버를 건물에 대규모로 출시하는 것은 2022년까지 전체 인구의 87%가 사용할 수 있도록 하는 것을 목표로 2009년에 시작되었습니다.[297] 2017년[update] 기준 UN 국제전기통신연합은 정보통신 인프라 개발 분야에서 뉴질랜드를 13위로 평가하고 있습니다.[298]

과학기술

뉴질랜드의 초기 토착 과학에 대한 기여는 마오리가 헝가에 의해 농업 관행에 대한 축적된 지식과 질병 및 질병 치료에 대한 약초 요법의 효과에 대한 것이었습니다.[299] 1700년대 쿡의 항해와 1835년 다윈의 항해는 중요한 과학적 식물학 및 동물학적 목적을 가지고 있었습니다.[300] 19세기의 대학 설립은 원자를 분열시킨 어니스트 러더퍼드, 로켓 과학을 위한 윌리엄 피커링, DNA 발견을 도운 모리스 윌킨스, 은하 형성을 위한 베아트리체 틴슬리, 성형을 위한 아치볼드 맥킨도 등 저명한 뉴질랜드인들의 과학적 발견을 촉진시켰습니다. 그리고 전도성 폴리머를 위한 앨런 맥 디아미드.[301]

크라운 연구소(CRIS)는 1992년에 기존 정부 소유의 연구 기관에서 구성되었습니다. 그들의 역할은 뉴질랜드의 이익을 위해 경제적, 환경적, 사회적, 문화적 스펙트럼에 걸쳐 새로운 과학, 지식, 제품 및 서비스를 연구하고 개발하는 것입니다.[302] GDP 대비 연구개발 총지출(R&D)은 2015년 1.23%에서 2018년 1.37%로 증가했습니다. 뉴질랜드는 GDP 대비 총 R&D 지출에서 OECD 21위를 차지했습니다.[303] 뉴질랜드는 2023년 글로벌 혁신 지수에서 27위를 차지했습니다.[304]

뉴질랜드 우주국은 2016년 정부에 의해 우주 정책, 규제 및 부문 개발을 위해 만들어졌습니다. 로켓 랩은 국내 최초의 상업용 로켓 발사기였습니다.[305]

인구통계학

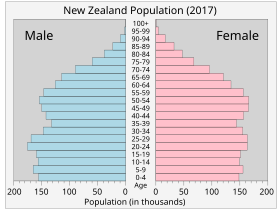

2018년 뉴질랜드 인구 조사에 따르면 거주 인구는 4,699,755명으로 2013년 인구 조사보다 10.8% 증가했습니다.[3] 2024년 2월 현재 총 인구는 5,275,830명으로 추정됩니다.[8] 뉴질랜드의 인구는 2020년 6월에 종료된 7년 동안 매년 1.9%씩 증가했습니다. 2020년 9월 뉴질랜드 통계청은 2018년 인구 조사를 기반으로 한 인구 추정에 따르면 2019년 9월 인구가 500만 명 이상으로 증가했다고 보고했습니다.[306][n 9]

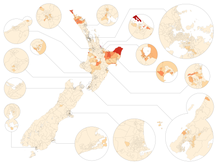

오늘날 뉴질랜드의 인구는 북부에 집중되어 있으며, 2023년 6월 현재 인구의 약 76.5%가 북섬에, 23.5%가 남섬에 살고 있습니다.[308] 20세기 동안 뉴질랜드의 인구는 북쪽으로 표류했습니다. 1921년에는 마나와투황가누이의 레빈 서쪽 태즈먼 해에 위치해 있었고, 2017년에는 와이카토의 카와이 근처까지 280km(170m) 북쪽으로 이동했습니다.[309]

뉴질랜드는 인구의 84.2%가 도시 지역에 살고 있고, 인구가 10만 명이 넘는 7개 도시에 인구의 50.6%가 살고 있는 도시 국가입니다.[308] 140만 명이 넘는 주민이 살고 있는 오클랜드는 단연 가장 큰 도시입니다.[308] 뉴질랜드 도시들은 일반적으로 국제적인 거주 가능성 측정에서 높은 순위를 차지합니다. 예를 들어, 2016년에 오클랜드는 세계에서 세 번째로 살기 좋은 도시로 선정되었고 웰링턴은 머서 삶의 질 조사에 의해 12번째로 선정되었습니다.[310]

2018년 인구 조사에서 뉴질랜드 인구의 평균 연령은 37.4세였으며 [311]2017-2019년 기대 수명은 남성이 80.0세, 여성이 83.5세였습니다.[312] 뉴질랜드는 2020년 합계출산율이 1.6명으로 하위대체출산율을 보이고 있는 반면, 출산율은 OECD 평균을 상회하고 있습니다.[313][314] 2050년까지 중위연령은 43세, 60세 이상 인구 비율은 18%에서 29%[315]로 증가할 것으로 예상됩니다. 2016년 사망 원인은 암이 30.3%로 가장 많았고 허혈성 심장질환(14.9%), 뇌혈관질환(7.4%)[316]이 뒤를 이었습니다. 2016년[update] 기준 보건의료 총지출(민간부문 지출 포함)은 GDP의 9.2%입니다.[317]

| 순위 | 이름. | 지역 | 팝. | 순위 | 이름. | 지역 | 팝. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

오클랜드  크라이스트처치 | 1 | 오클랜드 | 오클랜드 | 1,478,800 | 11 | 포리루아 | 웰링턴 | 60,900 |  웰링턴  해밀턴 |

| 2 | 크라이스트처치 | 캔터베리 | 384,800 | 12 | 뉴플리머스 | 타라나키 | 59,600 | ||

| 3 | 웰링턴 | 웰링턴 | 215,200 | 13 | 로토루아 | 만 오브 플렌티 | 58,900 | ||

| 4 | 해밀턴 | 와이카토 | 185,300 | 14 | 황가레이 | 노스랜드 | 56,900 | ||

| 5 | 타우랑가 | 만 오브 플렌티 | 161,800 | 15 | 넬슨 | 넬슨 | 51,900 | ||

| 6 | 로어 허트 | 웰링턴 | 113,000 | 16 | 헤이스팅스 | 호크스베이 | 51,500 | ||

| 7 | 더니딘 | 오타고 | 106,200 | 17 | 인버카길 | 사우스랜드 | 51,000 | ||

| 8 | 파머스턴 노스 | Manawatū-Whanganui | 82,500 | 18 | 어퍼헛 | 웰링턴 | 45,400 | ||

| 9 | 네이피어 | 호크스베이 | 67,500 | 19 | 황가누이 | Manawatū-Whanganui | 42,800 | ||

| 10 | 히비스커스 해안 | 오클랜드 | 63,400 | 20 | 기스본 | 기스본 | 38,200 | ||

민족과 이민

2018년 인구 조사에서 뉴질랜드 주민의 71.8%가 유럽인으로, 16.5%가 마오리인으로 확인되었습니다. 다른 주요 민족으로는 아시아계(15.3%)와 태평양계(9.0%)가 있으며, 이들 중 3분의 2는 오클랜드 지역에 살고 있습니다.[n 3][3] 인구는 최근 수십 년 동안 더 다문화적이고 다양해졌습니다. 1961년 인구 조사에 따르면 뉴질랜드의 인구는 유럽인이 92%, 마오리족이 7%였으며 아시아와 태평양 소수 민족이 나머지 1%[318]를 공유했습니다.

뉴질랜드 시민의 대명사는 뉴질랜드인이지만 비공식적인 "키위"는 국제적으로[319] 그리고 현지인들에 의해 일반적으로 사용됩니다.[320] 마오리족의 외래어인 파케하(Pākeha)는 유럽계 뉴질랜드인을 지칭하는 데 사용되었지만, 일부 사람들은 이 이름을 거부합니다. 오늘날 이 단어는 점점 더 폴리네시아계 뉴질랜드인이 아닌 모든 사람들을 지칭하는 데 사용되고 있습니다.[321]

마오리족은 뉴질랜드에 도착한 최초의 사람들이었고, 그 다음으로 초기 유럽 정착민들이었습니다. 식민지화 이후, 이민자들은 주로 화이트 오스트레일리아 정책과 유사한 제한 정책 때문에 영국, 아일랜드 및 호주에서 왔습니다.[322] 또한 호주, 북미, 남미 및 남아프리카를 통한 간접 유럽 이민과 함께 네덜란드, 달마티아,[323] 독일 및 이탈리아 이민도 상당했습니다.[324][325] 제2차 세계대전 이후 순이주가 증가하였고, 1970년대와 1980년대에는 이민정책이 완화되고 아시아로부터의 이민이 촉진되었습니다.[325][326] 2009-10년 뉴질랜드 이민국은 연간 45,000-50,000개의 영주권 승인 목표를 세웠습니다. 이는 뉴질랜드 거주자 100명당 1명 이상의 새로운 이주자를 의미합니다.[327] 2018년 인구 조사에서 뉴질랜드에서 태어나지 않은 사람은 27.4%로 2013년 인구 조사의 25.2%보다 증가했습니다. 뉴질랜드 해외 출생 인구의 절반 이상(52.4%)이 오클랜드 지역에 살고 있습니다.[328] 영국은 뉴질랜드 이민자의 가장 큰 원천으로 남아 있으며, 전체 해외 출생 뉴질랜드인의 약 4분의 1이 그곳에서 태어났습니다. 다른 주요 해외 출생 뉴질랜드 인구의 원천은 중국, 인도, 호주, 남아프리카 공화국, 피지, 사모아입니다.[329] 유료 유학생의 수는 1990년대 후반에 급격히 증가하여 2002년에는 20,000명 이상이 공립 고등학교에서 공부했습니다.[330]

언어

영어는 인구의 95.4%가 사용하는 뉴질랜드의 주요 언어입니다.[3] 뉴질랜드 영어는 독특한 억양과 어휘를 가진 다양한 언어입니다.[332] 그것은 호주 영어와 비슷하고 북반구의 많은 화자들은 억양을 구별하지 못합니다.[333] 뉴질랜드 영어 방언과 다른 영어 방언 간의 가장 두드러진 차이점은 짧은 앞모음의 변화입니다. (키트에서와 같이) 짧은-이 소리는 슈와 소리(콤마와 어바웃에서와 같이)에 집중되어 있고, 짧은-이 소리(드레스에서와 같이)는 짧은-이 소리(트랩에서와 같이)에 집중되어 있으며, 짧은-이 소리는 짧은-이 소리(트랩에서와 같이)에 집중되어 있습니다. 숏-e 사운드로 이동했습니다.[334]

제2차 세계 대전 이후, 마오리는 학교와 직장에서 그들만의 언어(테레오 마오리)를 사용하는 것을 단념하거나 강요당했고, 그것은 일부 외딴 지역에서만 공동체 언어로 존재했습니다.[335] 1867년 원주민 학교법은 모든 학교에서 영어로 수업하도록 했고, 아이들이 마오리어를 말하는 것을 금지하는 공식적인 정책은 없었지만, 그렇게 하면 신체적 학대에 시달리는 사람들이 많았습니다.[336][337][338] 마오리어는 1987년 뉴질랜드의 공식 언어 중 하나로 선언되는 [339]등 최근 활성화 과정을 거치고 있으며,[340] 인구의 4.0%가 사용하고 있습니다.[3][n 10] 현재는 마오리어에 몰입하는 학교와 두 개의 텔레비전 채널이 주로 방송되고 있습니다.[342] 마오리와 영어 이름이 모두 공식적으로 인정된 곳이 많습니다.[343]

2018년 인구 조사에 따르면 [3]사모아어가 가장 널리 사용되는 비공식 언어 (2.2%)이며, 다음으로 "북중국어" (중화어 포함, 2.0%), 힌디어 (1.5%), 프랑스어 (1.2%)가 그 뒤를 이었습니다. 뉴질랜드 수화는 22,986명(0.5%)이 이해하는 것으로 보고되었으며, 2006년에 뉴질랜드의 공식 언어 중 하나가 되었습니다.[344]

종교

비록 그 사회가 세계에서 가장 세속적인 종교들 중 하나이지만, 기독교는 뉴질랜드에서 가장 지배적인 종교입니다.[346][347] 2018년 인구 조사에서 응답자의 44.7%가 하나 이상의 종교와 동일시되었으며, 그 중 37.0%가 기독교인이라고 응답했습니다. 또 다른 48.5%는 종교가 없다고 답했습니다.[n 11][3] 특정 기독교 교단에 가입한 사람들 중 성공회(6.7%),[n 12] 로마 가톨릭(6.3%), 장로교(4.7%)[3] 등이 주요 응답입니다. 마오리족에 기반을 둔 링가투(Ringatu)와 라타나(Rātana) 교파(1.2%)도 기원이 기독교입니다.[3][345] 최근 수십 년 동안 이민과 인구 변화는 힌두교(2.6%), 이슬람교(1.3%), 불교(1.1%), 시크교(0.9%)[3]와 같은 소수 종교의 성장에 기여했습니다. 오클랜드 지역은 가장 큰 종교적 다양성을 보였습니다.[348]

교육

초등 및 중등 교육은 6세에서 16세 사이의 어린이에게 의무적으로 실시되며, 대부분의 어린이는 5세까지 참석합니다.[349] 13개의 학년이 있으며 뉴질랜드 시민과 영주권자는 5번째 생일부터 19번째 생일 이후 역년이 끝날 때까지 무료로 주립(공립)학교에 다닐 수 있습니다.[350] 뉴질랜드의 성인 문맹률은 99%[186]이며, 15세에서 29세 사이의 인구 중 절반 이상이 3차 자격을 가지고 있습니다.[349] 정부가 소유한 고등교육기관에는 대학, 사범대학, 폴리텍, 전문대학, 와낭가 등 5개 유형이 있으며,[351] 민간교육기관도 있습니다.[352] 2021년 25-64세 인구 중 13%는 정식 자격이 없었고, 21%는 학교 자격이 있었으며, 28%는 3차 자격증 또는 졸업장을 가지고 있었으며, 35%는 학사 학위 이상을 가지고 있었습니다.[353] OECD의 국제 학생 평가 프로그램은 뉴질랜드를 OECD 수학 부문 28위, 과학 부문 13위, 읽기 부문 11위로 평가하고 있습니다.[354]

문화

초기 마오리는 열대에 기반을 둔 동 폴리네시아 문화를 더 크고 다양한 환경과 관련된 도전에 따라 적응시켰고, 결국 그들만의 독특한 문화를 발전시켰습니다. 사회 조직은 주로 가족(화나우), 하위 부족(하푸), 족장(랑가티라)이 통치하는 부족(이위)과 공동체를 이루었고, 그 지위는 공동체의 승인을 받아야 했습니다.[355] 영국과 아일랜드 이민자들은 뉴질랜드에 자국 문화의 측면을 가져왔고 특히 기독교의 도입과 함께 [356][357]마오리 문화에도 영향을 미쳤습니다.[358] 그러나 마오리족은 여전히 부족 집단에 대한 충성심을 그들의 정체성의 중요한 부분으로 간주하고 있으며, 마오리족의 친족 역할은 다른 폴리네시아 민족의 그것과 유사합니다.[359] 최근에는 미국, 호주, 아시아 및 기타 유럽 문화가 뉴질랜드에 영향력을 행사하고 있습니다. 세계 최대의 폴리네시아 축제인 파시피카(Pasifika)가 이제 오클랜드(Auckland)에서 매년 열리는 행사로, 비마오리 폴리네시아 문화도 분명합니다.[360]

초기 뉴질랜드의 농촌 생활은 뉴질랜드인들이 투박하고 근면한 문제 해결자라는 이미지로 이어졌습니다.[361] 높은 성취자들이 혹독한 비판을 받았던 "키 큰 양귀비 증후군"을 통해 겸손함이 기대되고 강요되었습니다.[362] 당시 뉴질랜드는 지식인 국가로 알려져 있지 않았습니다.[363] 20세기 초부터 1960년대 후반까지 마오리 문화는 마오리를 영국계 뉴질랜드인으로 동화하려는 시도로 인해 억압되었습니다.[335] 1960년대에 고등교육이 보편화되고 도시가 확장되면서[364] 도시문화가 지배하기 시작했습니다.[365] 그러나 시골의 이미지와 주제는 뉴질랜드의 예술, 문학 및 미디어에서 흔히 볼 수 있습니다.[366]

뉴질랜드의 국가 상징은 자연적, 역사적, 마오리족의 영향을 받았습니다. 은고사리는 육군 휘장과 스포츠 팀 유니폼에 등장하는 엠블럼입니다.[367] 뉴질랜드의 독특한 것으로 생각되는 대중 문화의 특정 항목은 "키위아나"라고 불립니다.[367]

예체능

마오리 문화의 부활의 일환으로 조각과 직조의 전통 공예가 이제는 더 널리 행해지고 있으며, 마오리 예술가들의 수와 영향력이 증가하고 있습니다.[368] 대부분의 마오리 조각들은 사람의 형상을 형상화하고 있는데, 일반적으로 세 개의 손가락과 자연스럽게 생긴 세부적인 머리 또는 기괴한 머리를 가지고 있습니다.[369] 나선형, 능선, 노치, 물고기 비늘로 구성된 표면 패턴이 대부분의 조각을 장식합니다.[370] 마오리 건축은 상징적인 조각들과 삽화들로 장식된 조각된 모임의 집들로 구성되었습니다. 이 건물들은 원래 지속적으로 재건되어 다양한 변덕이나 요구에 따라 변화하고 적응하도록 설계되었습니다.[371]

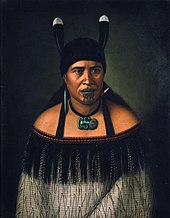

마오리는 건물, 카누, 세노타프의 흰 나무를 붉은 황토와 상어 지방의 혼합물인 검은색 페인트로 장식하고 동굴 벽에 새, 파충류 그리고 다른 디자인의 그림을 그렸습니다.[372] 검을 섞은 색의 그을음으로 이루어진 마오리 문신(모코)은 뼈 끌로 살을 깎았습니다.[373] 유럽 도착 그림과 사진은 원래 예술 작품이 아니라 뉴질랜드의 사실적인 묘사인 풍경에 의해 지배되었습니다.[374] 마오리의 초상화도 흔했는데, 초기 화가들은 종종 그들을 문명에 오염되지 않은 이상적인 인종으로 묘사했습니다.[374] 그 나라의 고립은 지역 예술가들이 그들만의 독특한 스타일의 지역주의를 개발할 수 있도록 유럽 예술 트렌드의 영향을 지연시켰습니다.[375] 1960년대와 1970년대 동안 많은 예술가들이 전통적인 마오리 기법과 서양 기법을 결합하여 독특한 예술 형태를 만들었습니다.[376] 뉴질랜드 미술과 공예는 2001년 베니스 비엔날레와 2004년 뉴욕에서 열린 "Paradise Now" 전시회를 통해 점차 국제적인 관객을 확보하고 있습니다.[368][377]

마오리 망토는 가는 아마 섬유로 만들어졌으며 검은색, 빨간색 및 흰색 삼각형, 다이아몬드 및 기타 기하학적 모양으로 무늬가 있습니다.[378] 그린스톤은 귀걸이와 목걸이로 제작되었으며, 가장 잘 알려진 디자인은 하이티키로, 머리를 옆으로 젖힌 채 다리를 꼬고 앉아 있는 왜곡된 인간 형상입니다.[379] 유럽인들은 영국 패션 에티켓을 뉴질랜드에 가져왔고, 1950년대까지 대부분의 사람들은 사교 행사를 위해 옷을 입었습니다.[380] 그 이후로 기준이 완화되었고 뉴질랜드 패션은 캐주얼하고 실용적이며 러스티가 부족하다는 평판을 받았습니다.[381][382] 그러나 국내 패션 산업은 2000년 이후 크게 성장하여 수출을 두 배로 늘리고 소수에서 약 50개의 기존 레이블로 증가했으며 일부 레이블은 국제적인 인정을 받았습니다.[382]

문학.

마오리는 빠르게 사상을 공유하는 수단으로 글쓰기를 채택했고, 그들의 구술이나 시의 상당수가 글쓰기 형식으로 전환되었습니다.[383] 대부분의 초기 영어 문학은 영국에서 얻어졌으며, 1950년대에 이르러서야 현지 출판사들이 증가하면서 비로소 뉴질랜드 문학이 널리 알려지기 시작했습니다.[384] 비록 여전히 세계적인 추세(모더니즘)와 사건(대공황)에 의해 크게 영향을 받았지만, 1930년대의 작가들은 점점 더 뉴질랜드에서의 경험에 초점을 맞추어 이야기를 전개하기 시작했습니다. 이 기간 동안 문학은 저널리즘 활동에서 더 학문적인 추구로 바뀌었습니다.[385] 세계 대전에 참여하면서 일부 뉴질랜드 작가들은 뉴질랜드 문화에 대한 새로운 관점을 갖게 되었고 전후 대학의 지역 문학이 번성했습니다.[386] 더니딘은 유네스코 문학 도시입니다.[387]

미디어 및 엔터테인먼트

뉴질랜드 음악은 블루스, 재즈, 컨트리, 로큰롤, 힙합의 영향을 받았으며, 이들 장르 중 많은 부분이 뉴질랜드 특유의 해석을 받았습니다.[388] 마오리는 그들의 고대 동남아시아 기원에서 전통적인 성가와 노래를 발전시켰고, 수세기 동안 고립된 후 독특한 "단조적"이고 "고통스러운" 소리를 만들었습니다.[389] 플루트와 트럼펫은 전쟁이나 특별한 경우에 악기나[390] 신호 장치로 사용되었습니다.[391] 초기 정착민들은 브라스 밴드와 합창 음악이 인기가 있었고 음악가들은 1860년대에 뉴질랜드를 순회하기 시작했습니다.[392][393] 파이프 밴드는 20세기 초에 널리 퍼졌습니다.[394] 뉴질랜드 음반 산업은 1940년 이후부터 발전하기 시작했고, 많은 뉴질랜드 음악가들은 영국과 미국에서 성공을 거두었습니다.[388] 일부 예술가들은 마오리어 노래를 발표하고, 마오리 전통을 바탕으로 한 카파하카(노래와 춤) 예술이 부활했습니다.[395] 뉴질랜드 뮤직 어워드는 레킷 앤 콜먼이 록신 골든 디스크 상으로 1965년에 처음 개최했습니다.[396] 레코딩 뮤직 NZ는 또한 미국의 공식 주간 음반 차트를 발행합니다.[397]

공영 라디오는 1922년 뉴질랜드에서 도입되었습니다.[399] 국영 텔레비전 서비스는 1960년에 시작되었습니다.[400] 1980년대의 규제 완화로 라디오와 텔레비전 방송국의 수가 갑자기 증가했습니다.[401] 뉴질랜드 텔레비전은 주로 미국과 영국의 프로그램을 방송하며, 많은 호주 및 지역 프로그램을 방송합니다.[402] 뉴질랜드 영화의 수는 1970년대에 상당히 증가했습니다. 1978년 뉴질랜드 영화 위원회는 현지 영화 제작자들을 돕기 시작했고, 많은 영화들이 세계적인 관객을 얻었으며, 어떤 영화들은 국제적인 인정을 받았습니다.[401] 뉴질랜드에서 가장 높은 수익을 올린 영화는 '헌트 포 더 와일더 피플', '소년', '세계에서 가장 빠른 인디언', '웨일 라이더', '원스 워 워리어스', '천상의 창조물', '피아노'입니다.[403] 뉴질랜드의 다양한 풍경과 컴팩트한 크기, 그리고 정부의 인센티브는 [404]반지의 제왕과 호빗 영화 삼부작, 아바타, 나니아 연대기, 킹콩, 울버린, 라스트 사무라이, 그리고 더 파워 오브 더 도그를 포함한 매우 큰 예산과 잘 알려진 작품들을 뉴질랜드에서 촬영하도록 일부 제작자들을 격려했습니다.[405] 뉴질랜드 미디어 산업은 소수의 회사들에 의해 지배되고 있으며, 이들 중 대부분은 외국인 소유이지만, 주정부는 일부 텔레비전과 라디오 방송국의 소유권을 유지하고 있습니다.[406] 1994년부터 프리덤 하우스는 2015년 기준으로 19번째로 자유로운 언론을 보유한 뉴질랜드의 언론 자유를 꾸준히 상위 20위 안에 들었습니다.[update][407]

스포츠

뉴질랜드에서 행해지는 대부분의 주요 스포츠 코드는 영국에서 유래했습니다.[408] 럭비 유니온은 국민 스포츠로[409] 여겨지며 가장 많은 관중을 끌어 모읍니다.[410] 골프, 네트볼, 테니스, 크리켓은 성인 참가율이 가장 높고 네트볼, 럭비 유니온, 축구(축구)는 특히 젊은이들 사이에서 인기가 높습니다.[410][411] 경마는 뉴질랜드에서 가장 인기 있는 관중 스포츠 중 하나이며 1960년대에는 "럭비, 경주 및 맥주" 하위 문화의 일부였습니다.[412] 뉴질랜드 청소년의 약 54%가 학교를 위한 스포츠에 참여합니다.[411] 1880년대 후반과 1900년대 초반의 호주와 영국의 승리적인 럭비 투어는 국가 정체성을 심어주는 초기 역할을 했습니다.[413] 마오리 선수의 유럽 스포츠 참여는 럭비에서 특히 두드러졌으며, 유럽 국가의 팀은 국제 경기 전에 전통적인 마오리 챌린지인 하카를 수행합니다.[414] 뉴질랜드는 유명한 뉴질랜드인 에드먼드 힐러리 경의 성공에서 볼 수 있듯이 극한의 스포츠, 모험 관광[415], 그리고 강한 산악 전통으로 유명합니다.[416][417] 자전거 타기, 낚시, 수영, 달리기, 짓밟기, 카누, 사냥, 스노우 스포츠, 서핑 및 세일링과 같은 다른 야외 활동도 인기가 있습니다.[418] 뉴질랜드는 1995년부터 아메리카 컵 레가타에서 정기적인 항해 성공을 거두었습니다.[419] 폴리네시아의 와카마 레이싱 스포츠는 1980년대 이후 뉴질랜드에서 다시 관심을 갖게 되었습니다.[420]

뉴질랜드는 럭비 유니온, 럭비 리그, 네트볼, 크리켓, 소프트볼, 요트 등에서 경쟁력 있는 국제 팀을 보유하고 있습니다. 뉴질랜드는 1908년과 1912년 하계 올림픽에 호주와 공동으로 참가한 후 1920년에 처음으로 단독으로 참가했습니다.[421] 이 나라는 최근 올림픽에서 메달 대 인구 비율에서 높은 순위를 차지했습니다.[422][423] 럭비 유니온 국가대표팀인 올 블랙스는 국제 럭비[424] 역사상 가장 성공적이며 월드컵에서 세 번 우승한 경험이 있습니다.[425]

요리.

민족 요리는 유럽, 폴리네시아 및 아시아에서 온 정착민과 이민자가 소개한 토착 마오리 요리와 다양한 요리 전통을 통합하여 환태평양 요리로 묘사되었습니다.[426] 뉴질랜드의 수확물은 육지와 바다에서 생산됩니다. 옥수수, 감자, 돼지와 같은 대부분의 작물과 가축은 초기 유럽 정착민들에 의해 점진적으로 도입되었습니다.[427] 독특한 재료 또는 요리로는 양고기, 연어, 코우라,[428] 블러프 굴, 화이트베이트, 파우아, 홍합, 가리비, 피피, 투아투아(뉴질랜드산 조개류의 일종),[429] 쿠마라(고구마), 키위, 타마릴로, 파블로바(국민 디저트로 간주됨)가 있습니다.[430][426] 한항 ī는 구덩이 오븐에 묻힌 가열된 바위를 이용하여 음식을 요리하는 전통적인 마오리 방식입니다; 여전히 탕기항가와 같은 특별한 날에 대규모 그룹을 위해 사용됩니다.

참고 항목

각주

- ^ "신이여 왕을 구하소서"는 공식적으로 국가이지만 일반적으로 정규 및 비정규 행사에만 사용됩니다.[1]

- ^ 영어는 널리 사용되기 때문에 사실상의 공용어입니다.[2]

- ^ a b 민족성 수치는 사람들이 하나 이상의 민족을 선택할 수 있기 때문에 100% 이상을 추가합니다.

- ^ 마오리에 기반을 둔 라타나 교회와 링가투 교회를 제외하고

- ^ 뉴질랜드 토지 피복 데이터베이스의 수치에 따르면 강, 호수 및 연못으로 덮인 뉴질랜드 면적(어초 제외)의 비율은 (357526 + 81936) / (26821559 – 92499 – 26033 – 19216) = 1.6%입니다. 하구 개방수, 맹그로브, 초식염수 식생을 포함하면 수치는 2.2%입니다.

- ^ 채텀 제도에는 뉴질랜드의 나머지 지역보다 45분 빠른 별도의 시간대가 있습니다.

- ^ 시계는 9월의 마지막 일요일에서 4월의 첫 일요일까지 한 시간씩 앞당겨집니다.[13] 채텀 제도에서도 NZDT보다 45분 빠른 일광 절약 시간이 관찰됩니다.

- ^ 2006년 1월 1일 이후 출생한 사람은 적어도 한 부모가 뉴질랜드 시민권자 또는 영주권자인 경우에만 출생 시 뉴질랜드 시민권을 취득합니다. 2005년 12월 31일 이전에 출생한 모든 사람은 출생 시 시민권을 취득했습니다(just soli).[179]

- ^ 잠정 추정치는 처음에 인구 추정치가 2013년 인구 조사에서 2018년 인구 조사로 다시 기반을 두기 전인 2020년 3월에 이정표에 도달했음을 나타냅니다.[307]

- ^ 2015년 마오리 성인(15세 이상)의 55%가 테레오 마오리에 대해 알고 있다고 보고했습니다. 이들 중 64%는 가정에서 마오리어를 사용하고 5만 명은 "매우 잘" 또는 "잘" 언어를 구사할 수 있습니다.[341]

- ^ 사람들이 여러 종교를 주장하거나 질문에 대답하는 것에 반대할 수 있기 때문에 종교 비율은 100%에 추가되지 않을 수 있습니다.

- ^ 이것은 인구조사에 대한 전체 응답자의 비율이지 기독교인의 비율이 아닙니다.

인용문

- ^ "Protocol for using New Zealand's National Anthems". Ministry for Culture and Heritage. Archived from the original on 11 May 2011. Retrieved 17 February 2008.

- ^ International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights Fifth Periodic Report of the Government of New Zealand (PDF) (Report). New Zealand Government. 21 December 2007. p. 89. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 January 2015. Retrieved 18 November 2015.

In addition to the Māori language, New Zealand Sign Language is also an official language of New Zealand. The New Zealand Sign Language Act 2006 permits the use of NZSL in legal proceedings, facilitates competency standards for its interpretation and guides government departments in its promotion and use. English, the medium for teaching and learning in most schools, is a de facto official language by virtue of its widespread use. For these reasons, these three languages have special mention in the New Zealand Curriculum.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Quick stats about ethnicity for New Zealand (2018 Census)". Statistics New Zealand. Source: Stats NZ and licensed by Stats NZ for reuse under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International licence. Archived from the original on 14 November 2023. Retrieved 14 November 2023.

- ^ "Quick stats about religion for New Zealand (2018 Census)". Statistics New Zealand. Source: Stats NZ and licensed by Stats NZ for reuse under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International licence. Archived from the original on 14 November 2023. Retrieved 14 November 2023.

- ^ "Treaty of Waitangi". mch.govt.nz. Manatū Taonga Ministry for Culture and Heritage. Archived from the original on 22 June 2023. Retrieved 22 June 2023.

- ^ "New Zealand country profile". BBC News. 20 November 2023. Archived from the original on 5 February 2024. Retrieved 20 November 2023.

- ^ "The New Zealand Land Cover Database". New Zealand Land Cover Database 2. Ministry for the Environment. 1 July 2009. Archived from the original on 14 March 2011. Retrieved 26 April 2011.

- ^ a b "Population clock". Statistics New Zealand. Archived from the original on 19 November 2022. Retrieved 15 May 2021. 표시된 인구 추정치는 UTC 00:00에 매일 자동으로 계산되며 인용에 표시된 날짜의 인구 시계에서 얻은 데이터를 기반으로 합니다.

- ^ "2018 Census population and dwelling counts". Statistics New Zealand. 23 September 2019. Archived from the original on 7 March 2023. Retrieved 25 September 2019.

- ^ a b c d "World Economic Outlook Database, October 2023 Edition. (NZ)". International Monetary Fund. 10 October 2023. Archived from the original on 19 October 2023. Retrieved 12 October 2023.

- ^ Household income and housing-cost statistics: Year ended June 2022. Statistics New Zealand. 23 March 2023. Archived from the original on 7 October 2023. Retrieved 22 September 2023.

- ^ a b Human Development Report 2021/2022 (PDF). United Nations Development Programme. 8 September 2022. ISBN 978-9211264517. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 8 September 2022.

- ^ "New Zealand Daylight Time Order 2007 (SR 2007/185)". New Zealand Parliamentary Counsel Office. 6 July 2007. Archived from the original on 7 March 2017. Retrieved 6 March 2017.

- ^ 뉴질랜드에 대한 공식적인 모든 숫자의 날짜 형식은 없지만 정부 권장 사항은 일반적으로 호주 날짜와 시간 표기법을 따릅니다. 봐요.

- ^ a b "22 USC § 2321k - Designation of major non-NATO allies". law.cornell.edu. Legal Information Institute. Archived from the original on 17 September 2012. Retrieved 14 September 2012.

- ^ a b Lynch, Brian (2009). "THE TRANS-TASMAN WORLD: towards a closer understanding". New Zealand International Review. 34 (2): 25–27. JSTOR 45235895.

- ^ a b Wilson, John (March 2009). "European discovery of New Zealand – Tasman's achievement". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Archived from the original on 6 January 2012. Retrieved 24 January 2011.

- ^ Bathgate, John. "The Pamphlet Collection of Sir Robert Stout: Volume 44. Chapter 1, Discovery and Settlement". NZETC. Archived from the original on 24 July 2020. Retrieved 17 August 2018.

He named the country Staaten Land, in honour of the States-General of Holland, in the belief that it was part of the great southern continent.

- ^ Mackay, Duncan (1986). "The Search for the Southern Land". In Fraser, B. (ed.). The New Zealand Book of Events. Auckland: Reed Methuen. pp. 52–54.

- ^ Wood, James (1900). The Nuttall Encyclopaedia: Being a Concise and Comprehensive Dictionary of General Knowledge. London and New York: Frederick Warne & Co. p. iii. Retrieved 10 October 2016.

- ^ a b McKinnon, Malcolm (November 2009). "Place names – Naming the country and the main islands". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Archived from the original on 13 June 2018. Retrieved 24 January 2011.

- ^ Grant (Lord Glenelg), Charles (1836). "Extract of a Despatch from Lord Glenelg to Major-General Sir Richard Bourke, New South Wales". Archived from the original on 8 December 2021. Retrieved 20 March 2021 – via Waitangi Associates.

- ^ Palmer 2008, p. 41.

- ^ King 2003, p. 41.

- ^ 헤이, 매클래건 & 고든 2008, p. 72.

- ^ a b Mein Smith 2005, p. 6.

- ^ Brunner, Thomas (1851). The Great Journey: An expedition to explore the interior of the Middle Island, New Zealand, 1846-8. Royal Geographical Society. Archived from the original on 31 October 2021. Retrieved 13 June 2010.

- ^ a b Williamson, Maurice (10 October 2013). "Names of NZ's two main islands formalised" (Press release). New Zealand Government. Archived from the original on 8 October 2014. Retrieved 1 May 2017.

- ^ Ministry of Health (24 June 2021). "COVID-19: Elimination strategy for Aotearoa New Zealand". Archived from the original on 2 December 2021. Retrieved 15 July 2021.

- ^ Larner, Wendy (31 May 2021). "COVID-19 in Aotearoa New Zealand". Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand. 51 (sup1): S1–S3. Bibcode:2021JRSNZ..51S...1L. doi:10.1080/03036758.2021.1908208.

- ^ "Using 'Aotearoa' and 'New Zealand' together 'as it should be' - Jacinda Ardern". Newshub. 17 December 2019. Archived from the original on 18 July 2021. Retrieved 18 July 2021.

- ^ New Zealand Government. "Moriori and the Trustees of the Moriori Imi Settlement Trust and the Crown Deed of Settlement of Historical Claims" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 March 2022. Retrieved 20 July 2023.

- ^ Te Papa (25 August 2020). "Repatriation and return of karāpuna to Rēkohu". Archived from the original on 7 June 2023. Retrieved 20 July 2023.

- ^ Anderson, Atholl; Spriggs, Matthew (1993). "Late colonization of East Polynesia". Antiquity. 67 (255): 200–217. doi:10.1017/S0003598X00045324. ISSN 1745-1744. S2CID 162638670.

- ^ Jacomb, Chris; Anderson, Atholl; Higham, Thomas (1999). "Dating the first New Zealanders: The chronology of Wairau Bar". Antiquity. 73 (280): 420–427. doi:10.1017/S0003598X00088360. ISSN 1745-1744. S2CID 161058755.

- ^ Wilmshurst, J. M.; Hunt, T. L.; Lipo, C. P.; Anderson, A. J. (2010). "High-precision radiocarbon dating shows recent and rapid initial human colonization of East Polynesia". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 108 (5): 1815–20. Bibcode:2011PNAS..108.1815W. doi:10.1073/pnas.1015876108. PMC 3033267. PMID 21187404.

- ^ "Kupe". Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa. Archived from the original on 18 July 2023. Retrieved 14 March 2023.

- ^ "Kupe". archive.hokulea.com. Archived from the original on 29 March 2023. Retrieved 24 February 2023.

- ^ "2: Tangata Whenua". RNZ. 8 October 2019. Archived from the original on 24 February 2023. Retrieved 24 February 2023.

- ^ McConnell, Joseph R.; Chellman, Nathan J.; Mulvaney, Robert; Eckhardt, Sabine; Stohl, Andreas; Plunkett, Gill; Kipfstuhl, Sepp; Freitag, Johannes; Isaksson, Elisabeth; Gleason, Kelly E.; Brugger, Sandra O.; McWethy, David B.; Abram, Nerilie J.; Liu, Pengfei; Aristarain, Alberto J. (6 October 2021). "Hemispheric black carbon increase after the 13th-century Māori arrival in New Zealand". Nature. 598 (7879): 82–85. Bibcode:2021Natur.598...82M. doi:10.1038/s41586-021-03858-9. PMID 34616056. S2CID 238421371. Archived from the original on 6 March 2023. Retrieved 24 May 2023.

- ^ McGlone, M.; Wilmshurst, J. M. (1999). "Dating initial Maori environmental impact in New Zealand". Quaternary International. 59 (1): 5–16. Bibcode:1999QuInt..59....5M. doi:10.1016/S1040-6182(98)00067-6.

- ^ Murray-McIntosh, Rosalind P.; Scrimshaw, Brian J.; Hatfield, Peter J.; Penny, David (1998). "Testing migration patterns and estimating founding population size in Polynesia by using human mtDNA sequences". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 95 (15): 9047–52. Bibcode:1998PNAS...95.9047M. doi:10.1073/pnas.95.15.9047. PMC 21200. PMID 9671802.

- ^ Wilmshurst, J. M.; Anderson, A. J.; Higham, T. F. G.; Worthy, T. H. (2008). "Dating the late prehistoric dispersal of Polynesians to New Zealand using the commensal Pacific rat". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 105 (22): 7676–80. Bibcode:2008PNAS..105.7676W. doi:10.1073/pnas.0801507105. PMC 2409139. PMID 18523023.

- ^ Jacomb, Chris; Holdaway, Richard N.; Allentoft, Morten E.; Bunce, Michael; Oskam, Charlotte L.; Walter, Richard; Brooks, Emma (2014). "High-precision dating and ancient DNA profiling of moa (Aves: Dinornithiformes) eggshell documents a complex feature at Wairau Bar and refines the chronology of New Zealand settlement by Polynesians". Journal of Archaeological Science. 50: 24–30. Bibcode:2014JArSc..50...24J. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2014.05.023. Archived from the original on 1 October 2022. Retrieved 22 March 2020.

- ^ Walters, Richard; Buckley, Hallie; Jacomb, Chris; Matisoo-Smith, Elizabeth (7 October 2017). "Mass Migration and the Polynesian Settlement of New Zealand". Journal of World Prehistory. 30 (4): 351–376. doi:10.1007/s10963-017-9110-y.

- ^ Roberton, J. B. W. (1956). "Genealogies as a basis for Maori chronology". Journal of the Polynesian Society. 65 (1): 45–54. Archived from the original on 10 March 2020. Retrieved 22 March 2020.

- ^ Te Hurinui, Pei (1958). "Maori genealogies". Journal of the Polynesian Society. 67 (2): 162–165. Archived from the original on 12 February 2018. Retrieved 22 March 2020.

- ^ Moodley, Y.; Linz, B.; Yamaoka, Y.; et al. (2009). "The Peopling of the Pacific from a Bacterial Perspective". Science. 323 (5913): 527–530. Bibcode:2009Sci...323..527M. doi:10.1126/science.1166083. PMC 2827536. PMID 19164753.

- ^ Walter, Richard; Buckley, Hallie; Jacomb, Chris; Matisoo-Smith, Elizabeth (1 December 2017). "Mass Migration and the Polynesian Settlement of New Zealand". Journal of World Prehistory. 30 (4): 351–376. doi:10.1007/s10963-017-9110-y. ISSN 1573-7802. S2CID 254743326.

- ^ Ballara, Angela (1998). Iwi: The Dynamics of Māori Tribal Organisation from c. 1769 to c. 1945 (1st ed.). Wellington: Victoria University Press. ISBN 9780864733283.

- ^ Clark, Ross (1994). "Moriori and Māori: The Linguistic Evidence". In Sutton, Douglas (ed.). The Origins of the First New Zealanders. Auckland: Auckland University Press. pp. 123–135.

- ^ Davis, Denise (September 2007). "The impact of new arrivals". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Archived from the original on 19 April 2023. Retrieved 30 April 2010.

- ^ Davis, Denise; Solomon, Māui (March 2009). "Moriori – The impact of new arrivals". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Archived from the original on 19 April 2023. Retrieved 23 March 2011.

- ^ Mitchell, Hillary (10 February 2015). "Te Tau Ihu". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Ministry for Culture and Heritage. Archived from the original on 28 August 2016. Retrieved 15 September 2016.

- ^ a b Mein Smith 2005, p. 23.

- ^ Salmond, Anne (1991). Two Worlds: First Meetings Between Maori and Europeans 1642–1772. Auckland: Penguin Books. p. 82. ISBN 0-670-83298-7.

- ^ King 2003, p. 122.

- ^ Fitzpatrick, John (2004). "Food, warfare and the impact of Atlantic capitalism in Aotearo/New Zealand" (PDF). Australasian Political Studies Association Conference: APSA 2004 Conference Papers. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 May 2011.

- ^ Brailsford, Barry (1972). Arrows of Plague. Wellington: Hick Smith and Sons. p. 35. ISBN 0-456-01060-2.

- ^ Wagstrom, Thor (2005). "Broken Tongues and Foreign Hearts". In Brock, Peggy (ed.). Indigenous Peoples and Religious Change. Boston: Brill Academic Publishers. pp. 71 and 73. ISBN 978-90-04-13899-5.

- ^ Lange, Raeburn (1999). May the people live: a history of Māori health development 1900–1920. Auckland University Press. p. 18. ISBN 978-1-86940-214-3.

- ^ a b c Orange, Claudia (1990). "Busby, James – Biography". In Oliver, W. H.; Orange, Claudia; Phillips, Jock (eds.). Dictionary of New Zealand Biography, Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Archived from the original on 27 June 2013. Retrieved 7 January 2011.

- ^ "First British Resident comes ashore". NZHistory. New Zealand Ministry for Culture and Heritage. 24 December 2020. Archived from the original on 18 October 2021. Retrieved 19 October 2021.

- ^ Foster, Bernard John (April 2009) [1966]. "Sir George Gipps". In McLintock, Alexander Hare (ed.). An Encyclopaedia of New Zealand. Archived from the original on 17 January 2013. Retrieved 20 March 2021 – via TeAra.govt.nz.

- ^ a b Wilson, John (16 September 2016) [2005]. "Nation and government – The origins of nationhood". In Phillips, Jock (ed.). Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Archived from the original on 24 May 2018. Retrieved 20 March 2021.

- ^ McLintock, Alexander Hare, ed. (April 2009) [1966]. "Settlement from 1840 to 1852". An Encyclopaedia of New Zealand. Archived from the original on 20 January 2013. Retrieved 7 January 2011 – via TeAra.govt.nz.

- ^ Foster, Bernard John (April 2009) [1966]. "Akaroa, French Settlement At". In McLintock, Alexander Hare (ed.). An Encyclopaedia of New Zealand. Archived from the original on 20 January 2013. Retrieved 7 January 2011 – via TeAra.govt.nz.

- ^ Simpson, K. A. (1990). "Hobson, William – Biography". In Oliver, W. H.; Orange, Claudia; Phillips, Jock (eds.). Dictionary of New Zealand Biography, Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Archived from the original on 20 August 2017. Retrieved 20 March 2021.

- ^ Phillips, Jock (1 August 2015) [2005]. "History of immigration – British immigration and the New Zealand Company". In Phillips, Jock (ed.). Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Archived from the original on 10 March 2021. Retrieved 20 March 2021.

- ^ "Crown colony era – the Governor-General". NZHistory. New Zealand Ministry for Culture and Heritage. March 2009. Archived from the original on 2 March 2011. Retrieved 7 January 2011.

- ^ Moon, Paul (2010). New Zealand Birth Certificates – 50 of New Zealand's Founding Documents. AUT Media. p. 66. ISBN 978-0-95829971-8.

- ^ "New Zealand's 19th-century wars – overview". NZHistory. New Zealand Ministry for Culture and Heritage. April 2009. Archived from the original on 14 November 2016. Retrieved 7 January 2011.

- ^ a b c Wilson, John (16 September 2016) [2005]. "Government and nation – From colony to nation". In Phillips, Jock (ed.). Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Archived from the original on 26 December 2018. Retrieved 2 February 2011.

- ^ Temple, Philip (1980). Wellington Yesterday. John McIndoe. ISBN 0-86868-012-5.

- ^ Levine, Stephen (13 July 2012). "Capital city – A new capital". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Archived from the original on 5 May 2015. Retrieved 4 May 2015.

- ^ "Parliament moves to Wellington". NZHistory. New Zealand Ministry for Culture and Heritage. January 2017. Archived from the original on 25 April 2019. Retrieved 27 April 2017.

- ^ Jobberns, George (1966). "Kermadec Islands". In McLintock, A. H. (ed.). An Encyclopaedia of New Zealand, Te Ara. Archived from the original on 19 March 2022. Retrieved 18 March 2022.

- ^ "Pacific Island Exclusive Economic Zones". TEARA. Archived from the original on 24 October 2022. Retrieved 24 October 2022.

- ^ a b Wilson, John (March 2009). "History – Liberal to Labour". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Archived from the original on 27 April 2017. Retrieved 27 April 2017.

- ^ Hamer, David. "Seddon, Richard John". Dictionary of New Zealand Biography. Ministry for Culture and Heritage. Retrieved 27 April 2017.

- ^ Boxall, Peter; Haynes, Peter (1997). "Strategy and Trade Union Effectiveness in a Neo-liberal Environment". British Journal of Industrial Relations. 35 (4): 567–591. doi:10.1111/1467-8543.00069. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 May 2011.

- ^ "A brief history of the minimum wage in New Zealand". Newshub. Archived from the original on 19 July 2022. Retrieved 19 July 2022.

- ^ "Proclamation". The London Gazette. No. 28058. 10 September 1907. p. 6149.

- ^ "Dominion status – Becoming a dominion". NZHistory. New Zealand Ministry for Culture and Heritage. September 2014. Archived from the original on 14 June 2020. Retrieved 26 April 2017.

- ^ "War and Society". New Zealand Ministry for Culture and Heritage. Archived from the original on 9 November 2016. Retrieved 7 January 2011.

- ^ Easton, Brian (April 2010). "Economic history – Interwar years and the great depression". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Archived from the original on 16 May 2011. Retrieved 7 January 2011.

- ^ Derby, Mark (May 2010). "Strikes and labour disputes – Wars, depression and first Labour government". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Archived from the original on 23 January 2011. Retrieved 1 February 2011.

- ^ Easton, Brian (November 2010). "Economic history – Great boom, 1935–1966". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Archived from the original on 16 May 2011. Retrieved 1 February 2011.

- ^ Keane, Basil (November 2010). "Te Māori i te ohanga – Māori in the economy – Urbanisation". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Archived from the original on 16 May 2011. Retrieved 7 January 2011.

- ^ Royal, Te Ahukaramū (March 2009). "Māori – Urbanisation and renaissance". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Archived from the original on 20 January 2013. Retrieved 1 February 2011.

- ^ Healing the Past, Building a Future: A Guide to Treaty of Waitangi Claims and Negotiations with the Crown (PDF). Office of Treaty Settlements. March 2015. ISBN 978-0-478-32436-5. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 January 2018. Retrieved 26 April 2017.

- ^ Report on the Crown's Foreshore and Seabed Policy (Report). Ministry of Justice. Archived from the original on 1 February 2019. Retrieved 26 April 2017.

- ^ Barker, Fiona (June 2012). "Debate about the foreshore and seabed". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Archived from the original on 18 July 2023. Retrieved 26 April 2017.

- ^ a b "New Zealand's Constitution". Office of the Governor-General of New Zealand. Archived from the original on 6 April 2003. Retrieved 13 January 2010.

- ^ a b c "Factsheet – New Zealand – Political Forces". The Economist. 15 February 2005. Archived from the original on 14 May 2006. Retrieved 4 August 2009.

- ^ "Royal Titles Act 1974". New Zealand Parliamentary Counsel Office. February 1974. Section 1. Archived from the original on 20 October 2008. Retrieved 8 January 2011.

- ^ Constitution Act 1986. New Zealand Parliamentary Counsel Office. 1 January 1987. Section 2.1. Archived from the original on 23 December 2016. Retrieved 15 July 2018.

The Sovereign in right of New Zealand is the head of State of New Zealand, and shall be known by the royal style and titles proclaimed from time to time.

- ^ "The Role of the Governor-General". Office of the Governor-General of New Zealand. 27 February 2017. Archived from the original on 29 June 2017. Retrieved 6 July 2017.

- ^ Harris, Bruce (2009). "Replacement of the Royal Prerogative in New Zealand". New Zealand Universities Law Review. 23: 285–314. Archived from the original on 18 July 2011. Retrieved 28 August 2016.

- ^ a b "The Reserve Powers". Office of the Governor-General of New Zealand. Archived from the original on 7 July 2017. Retrieved 8 January 2011.

- ^ a b c d "Parliament Brief: What is Parliament?". New Zealand Parliament. Archived from the original on 29 October 2020. Retrieved 30 November 2016.

- ^ McLean, Gavin (February 2015). "Premiers and prime ministers". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Archived from the original on 17 May 2017. Retrieved 30 November 2016.

- ^ Wilson, John (November 2010). "Government and nation – System of government". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Archived from the original on 16 May 2011. Retrieved 9 January 2011.

- ^ "Principles of Cabinet decision making". Cabinet Manual. Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet. 2008. Archived from the original on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 1 December 2016.

- ^ "Christopher Luxon sworn in as New Zealand's new prime minister". TVNZ. 1News. 27 November 2023. Archived from the original on 27 November 2023. Retrieved 27 November 2023.

- ^ "The electoral cycle". Cabinet Manual. Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet. 2008. Archived from the original on 27 January 2018. Retrieved 30 April 2017.

- ^ "First past the post – the road to MMP". New Zealand Ministry for Culture and Heritage. September 2009. Archived from the original on 1 July 2010. Retrieved 9 January 2011.

- ^ "Number of electorates and electoral populations: 2018 Census". Stats.Govt.nz. Statistics New Zealand. 23 September 2019. Archived from the original on 13 December 2019. Retrieved 9 March 2021.

- ^ "Sainte-Laguë allocation formula". Electoral Commission. 4 February 2013. Archived from the original on 14 September 2013. Retrieved 31 May 2014.

- ^ Curtin, Jennifer; Miller, Raymond (21 July 2015). "Political parties". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Archived from the original on 17 June 2023. Retrieved 24 July 2023.

- ^ "Role of the Chief Justice". Courts of New Zealand. Archived from the original on 25 March 2020. Retrieved 9 June 2018.

- ^ "Structure of the court system". Courts of New Zealand. Archived from the original on 12 June 2018. Retrieved 9 June 2018.

- ^ "The Judiciary". Ministry of Justice. Archived from the original on 24 November 2010. Retrieved 9 January 2011.

- ^ "Fragile States Index Heat Map". Fragile States Index. Archived from the original on 14 August 2020. Retrieved 18 August 2020.

- ^ "Democracy Index 2017" (PDF). Economist Intelligence Unit. 2018. p. 5. Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 February 2018. Retrieved 9 December 2018.

- ^ "Corruption Perceptions Index 2017". Transparency International. 21 February 2018. Archived from the original on 21 February 2018. Retrieved 9 December 2018.

- ^ Carroll, Aengus (May 2016). "State Sponsored Homophobia 2016: A world survey of sexual orientation laws: criminalisation, protection and recognition" (PDF). International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex Association. p. 183. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 September 2017. Retrieved 4 December 2016.

In Australia and New Zealand, lesbian, gay, and bisexual people continue to enjoy many legal rights denied to their comrades across the vast majority of the Pacific.

- ^ "New Zealand". OECD Better Life Index. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Archived from the original on 21 January 2023. Retrieved 31 January 2023.

- ^ "Council election turnout: Low participation revives call for online voting". RNZ. 10 October 2022. Archived from the original on 29 May 2023. Retrieved 29 May 2023.

- ^ "Auckland councillor says record low local election turnout 'extremely concerning'". NZ Herald. 30 May 2023. Archived from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 29 May 2023.

- ^ "The media and low local election turnout". RNZ. 13 October 2022. Archived from the original on 29 May 2023. Retrieved 29 May 2023.

- ^ "New Zealand". Country Reports on Human Rights Practices for 2017. United States Department of State. Archived from the original on 1 January 2020. Retrieved 9 December 2018.

- ^ "A fair go for all? Rite tahi tätou katoa? Addressing Structural Discrimination in Public Services". Human Rights Commission. 2012. p. 50. Archived from the original on 30 March 2014. Retrieved 22 July 2023.

- ^ Cornish, Sophie (1 May 2022). "Māori even more overrepresented in prisons, despite $98m strategy". Stuff. Archived from the original on 29 May 2023. Retrieved 29 May 2023.

- ^ "Hāpaitia te Oranga Tangata New Zealand Ministry of Justice". www.justice.govt.nz. Archived from the original on 1 June 2023. Retrieved 29 May 2023.

- ^ McLintock, Alexander, ed. (April 2009) [1966]. "External Relations". An Encyclopaedia of New Zealand. Archived from the original on 20 January 2013. Retrieved 7 January 2011.

- ^ "Michael Joseph Savage". New Zealand Ministry for Culture and Heritage. July 2010. Archived from the original on 27 September 2016. Retrieved 29 January 2011.

- ^ Patman, Robert (2005). "Globalisation, Sovereignty, and the Transformation of New Zealand Foreign Policy" (PDF). Working Paper 21/05. Centre for Strategic Studies, Victoria University of Wellington. p. 8. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 September 2007. Retrieved 12 March 2007.

- ^ "Department of External Affairs: Security Treaty between Australia, New Zealand and the United States of America". Australian Government. September 1951. Archived from the original on 29 June 2011. Retrieved 11 January 2011.

- ^ "The Vietnam War". New Zealand History. New Zealand Ministry for Culture and Heritage. June 2008. Archived from the original on 8 November 2016. Retrieved 11 January 2011.

- ^ "Sinking the Rainbow Warrior – nuclear-free New Zealand". New Zealand History. New Zealand Ministry for Culture and Heritage. August 2008. Archived from the original on 19 October 2016. Retrieved 11 January 2011.

- ^ "Nuclear-free legislation – nuclear-free New Zealand". New Zealand History. New Zealand Ministry for Culture and Heritage. August 2008. Archived from the original on 3 November 2016. Retrieved 11 January 2011.

- ^ Lange, David (1990). Nuclear Free: The New Zealand Way. Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-014519-2.

- ^ "Australia in brief". Australian Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade. Archived from the original on 22 December 2010. Retrieved 11 January 2011.

- ^ a b "New Zealand country brief". Australian Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade. Archived from the original on 12 October 2013. Retrieved 11 January 2011.

- ^ Collett, John (4 September 2013). "Kiwis face hurdles in pursuit of lost funds". Archived from the original on 6 September 2013. Retrieved 4 October 2013.

- ^ Mark, Simon (11 January 2021). "New Zealand's public diplomacy in the Pacific: a reset, or more of the same?". Place Branding and Public Diplomacy. 18 (2): 105–112. doi:10.1057/s41254-020-00196-x. ISSN 1751-8059. PMC 7798375. Archived from the original on 21 February 2024. Retrieved 7 March 2022.

- ^ Bertram, Geoff (April 2010). "South Pacific economic relations – Aid, remittances and tourism". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Archived from the original on 20 January 2013. Retrieved 11 January 2011.

- ^ Howes, Stephen (November 2010). "Making migration work: Lessons from New Zealand". Development Policy Centre. Archived from the original on 11 May 2011. Retrieved 23 March 2011.

- ^ Institute, Lowy. "New Zealand – Lowy Institute Asia Power Index". Lowy Institute Asia Power Index 2021. Archived from the original on 1 April 2022. Retrieved 7 March 2022.

- ^ "Caught between China and the US: The Kiwi place in a newly confrontational world". Stuff.co.nz. 7 June 2019. Archived from the original on 5 July 2019. Retrieved 1 May 2020.

- ^ Steff, Reuben (5 June 2018). "New Zealand's Pacific reset: strategic anxieties about rising China". University of Waikato. Archived from the original on 1 February 2019. Retrieved 1 May 2020.

- ^ "Member States of the United Nations". United Nations. Archived from the original on 30 December 2013. Retrieved 11 January 2011.

- ^ "New Zealand". The Commonwealth. 15 August 2013. Archived from the original on 1 December 2016. Retrieved 1 December 2016.

- ^ "Members and partners". Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Archived from the original on 8 April 2011. Retrieved 11 January 2011.

- ^ "The Future of the Five Power Defence Arrangements". The Strategist. Australian Strategic Policy Institute. 8 November 2012. Archived from the original on 2 December 2016. Retrieved 1 December 2016.

- ^ "About Us: Role and Responsibilities". New Zealand Defence Force. Archived from the original on 8 February 2013. Retrieved 11 January 2011.

- ^ Ayson, Robert (2007). "New Zealand Defence and Security Policy, 1990–2005". In Alley, Roderic (ed.). New Zealand in World Affairs. Vol. IV: 1990–2005. Wellington: Victoria University Press. p. 132. ISBN 978-0-86473-548-5.

- ^ "The Battle for Crete". New Zealand History. New Zealand Ministry for Culture and Heritage. May 2010. Archived from the original on 21 April 2009. Retrieved 9 January 2011.

- ^ "El Alamein – The North African Campaign". New Zealand History. New Zealand Ministry for Culture and Heritage. May 2009. Archived from the original on 4 January 2011. Retrieved 9 January 2011.

- ^ Holmes, Richard (September 2010). "World War Two: The Battle of Monte Cassino". Archived from the original on 28 January 2011. Retrieved 9 January 2011.

- ^ "Gallipoli stirred new sense of national identity says Clark". The New Zealand Herald. April 2005. Archived from the original on 29 April 2020. Retrieved 9 January 2011.

- ^ Prideaux, Bruce (2007). Ryan, Chris (ed.). Battlefield Tourism: History, Place and Interpretation. Elsevier Science. p. 18. ISBN 978-0-08-045362-0.

- ^ Burke, Arthur. "The Spirit of ANZAC". ANZAC Day Commemoration Committee. Archived from the original on 26 December 2010. Retrieved 11 January 2011.

- ^ "South African War 1899–1902". New Zealand Ministry for Culture and Heritage. February 2009. Archived from the original on 3 January 2011. Retrieved 11 January 2011.

- ^ "New Zealand in the Korean War". New Zealand History. New Zealand Ministry for Culture and Heritage. Archived from the original on 9 May 2020. Retrieved 1 December 2016.

- ^ "NZ and the Malayan Emergency". New Zealand Ministry for Culture and Heritage. August 2010. Archived from the original on 3 January 2011. Retrieved 11 January 2011.

- ^ "New Zealand Defence Force Overseas Operations". New Zealand Defence Force. January 2008. Archived from the original on 25 January 2008. Retrieved 17 February 2008.

- ^ "Five Eyes Intelligence Oversight and Review Council (FIORC)". www.dni.gov. Archived from the original on 21 January 2021. Retrieved 12 September 2022.

- ^ "Relations with New Zealand". NATO. Archived from the original on 3 April 2023. Retrieved 3 April 2023.

- ^ "Partnership arrangement signed with NATO". Beehive.co.nz. NZ Govt. Archived from the original on 3 April 2023. Retrieved 3 April 2023.

- ^ Scotcher, Katie (3 April 2023). "New Zealand's relationship to Nato is getting stronger, expert says". New Zealand Herald. Archived from the original on 3 April 2023. Retrieved 3 April 2023.

- ^ a b "New Zealand's Nine Provinces (1853–76)" (PDF). Friends of the Hocken Collections. University of Otago. March 2000. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 February 2011. Retrieved 13 January 2011.

- ^ McLintock, Alexander, ed. (April 2009) [1966]. "Provincial Divergencies". An Encyclopaedia of New Zealand. Archived from the original on 20 January 2013. Retrieved 7 January 2011.

- ^ Swarbrick, Nancy (September 2016). "Public holidays". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Archived from the original on 6 June 2017. Retrieved 25 June 2017.

- ^ "Overview – regional rugby". New Zealand Ministry for Culture and Heritage. September 2010. Archived from the original on 22 August 2016. Retrieved 13 January 2011.

- ^ Dollery, Brian; Keogh, Ciaran; Crase, Lin (2007). "Alternatives to Amalgamation in Australian Local Government: Lessons from the New Zealand Experience" (PDF). Sustaining Regions. 6 (1): 50–69. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 August 2007.

- ^ a b c Sancton, Andrew (2000). Merger mania: the assault on local government. McGill-Queen's University Press. p. 84. ISBN 0-7735-2163-1.

- ^ "Subnational population estimates at 30 June 2010 (boundaries at 1 November 2010)". Statistics New Zealand. 26 October 2010. Archived from the original on 10 June 2011. Retrieved 2 April 2011.

- ^ Smelt & Jui Lin 2009, p. 33.

- ^ a b "Glossary". Department of Internal Affairs. Archived from the original on 9 July 2023. Retrieved 28 August 2016.

- ^ "Chatham Islands Council Act 1995 No 41". New Zealand Parliamentary Counsel Office. 29 July 1995. Archived from the original on 8 August 2017. Retrieved 8 August 2017.

- ^ Gimpel, Diane (2011). Monarchies. ABDO Publishing Company. p. 22. ISBN 978-1-617-14792-0. Retrieved 18 November 2016.

- ^ "System of Government". Government of Niue. Archived from the original on 13 November 2010. Retrieved 13 January 2010.

- ^ "Government – Structure, Personnel". Government of the Cook Islands. Archived from the original on 20 January 2022. Retrieved 13 January 2010.

- ^ "Tokelau Government". Government of Tokelau. Archived from the original on 13 November 2016. Retrieved 16 November 2016.

- ^ "Scott Base". Antarctica New Zealand. Archived from the original on 29 March 2023. Retrieved 13 January 2010.

- ^ "Citizenship Act 1977 No 61". Zealand Parliamentary Counsel Office. 1 December 1977. Archived from the original on 25 February 2017. Retrieved 26 May 2017.

- ^ "Check if you're a New Zealand citizen". Department of Internal Affairs. Archived from the original on 23 September 2014. Retrieved 20 January 2015.

- ^ a b Walrond, Carl (8 February 2005). "Natural environment – Geography and geology". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Archived from the original on 21 February 2022. Retrieved 26 December 2020.

- ^ McLintock, Alexander, ed. (April 2009) [1966]. "The Sea Floor". An Encyclopaedia of New Zealand. Archived from the original on 20 January 2013. Retrieved 13 January 2011.

- ^ "Hauraki Gulf islands". Auckland City Council. Archived from the original on 25 December 2010. Retrieved 13 January 2011.

- ^ Hindmarsh (2006). "Discovering D'Urville". Heritage New Zealand. Archived from the original on 11 May 2011. Retrieved 13 January 2011.

- ^ "Distance tables". Auckland Coastguard. Archived from the original on 23 January 2011. Retrieved 2 March 2011.

- ^ McKenzie, D. W. (1987). Heinemann New Zealand atlas. Heinemann Publishers. ISBN 0-7900-0187-X.

- ^ a b c d e "New Zealand". The World Factbook. US Central Intelligence Agency. 25 February 2021. Archived from the original on 9 January 2021. Retrieved 20 March 2021.

- ^ "Geography". Statistics New Zealand. 1999. Archived from the original on 22 May 2010. Retrieved 21 December 2009.

- ^ Offshore Options: Managing Environmental Effects in New Zealand's Exclusive Economic Zone (PDF). Wellington: Ministry for the Environment. 2005. ISBN 0-478-25916-6. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 April 2019. Retrieved 23 June 2017.

- ^ Coates, Glen (2002). The rise and fall of the Southern Alps. Canterbury University Press. p. 15. ISBN 0-908812-93-0.

- ^ Garden 2005, p. 52.

- ^ Grant, David (March 2009). "Southland places – Fiordland's coast". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Archived from the original on 28 June 2012. Retrieved 14 January 2011.

- ^ "Central North Island volcanoes". New Zealand Department of Conservation. Archived from the original on 29 December 2010. Retrieved 14 January 2011.

- ^ "Taupō". GNS Science. Archived from the original on 24 March 2011. Retrieved 2 April 2011.

- ^ a b Lewis, Keith; Nodder, Scott; Carter, Lionel (March 2009). "Sea floor geology – Active plate boundaries". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Archived from the original on 20 January 2013. Retrieved 4 February 2011.

- ^ Wallis, G. P.; Trewick, S. A. (2009). "New Zealand phylogeography: Evolution on a small continent". Molecular Ecology. 18 (17): 3548–3580. Bibcode:2009MolEc..18.3548W. doi:10.1111/j.1365-294X.2009.04294.x. PMID 19674312. S2CID 22049973.

- ^ Mortimer, Nick; Campbell, Hamish (2014). Zealandia: Our Continent Revealed. Auckland: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-357156-8. OCLC 887230882.

- ^ Wright, Dawn; Bloomer, Sherman; MacLeod, Christopher; Taylor, Brian; Goodliffe, Andrew (2000). "Bathymetry of the Tonga Trench and Forearc: A Map Series". Marine Geophysical Researches. 21 (5): 489–512. Bibcode:2000MarGR..21..489W. doi:10.1023/A:1026514914220. S2CID 6072675.

- ^ Deverson, Tony; Kennedy, Graeme, eds. (2005). "Australasia". New Zealand Oxford Dictionary. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acref/9780195584516.001.0001. ISBN 9780195584516.

- ^ Hobbs, Joseph J. (2016). Fundamentals of World Regional Geography. Cengage Learning. p. 367. ISBN 9781305854956.

- ^ Hillstrom, Kevin; Collier Hillstrom, Laurie (2003). Australia, Oceania, and Antarctica: A Continental Overview of Environmental Issues. Vol. 3. ABC-Clio. p. 25. ISBN 9781576076941.

... defined here as the continent nation of Australia, New Zealand, and twenty-two other island countries and territories sprinkled over more than 40 million square kilometres of the South Pacific.

- ^ a b Mullan, Brett; Tait, Andrew; Thompson, Craig (March 2009). "Climate – New Zealand's climate". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Archived from the original on 20 January 2013. Retrieved 15 January 2011.

- ^ "Summary of New Zealand climate extremes". National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research. 2004. Archived from the original on 25 September 2023. Retrieved 30 April 2010.

- ^ Walrond, Carl (March 2009). "Natural environment – Climate". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Archived from the original on 20 January 2013. Retrieved 15 January 2011.

- ^ Orange, Claudia (1 May 2015). "Northland region". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Archived from the original on 11 August 2020. Retrieved 4 May 2020.

- ^ "Mean monthly rainfall". National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research. Archived from the original (XLS) on 3 May 2011. Retrieved 4 February 2011.

- ^ "Mean monthly sunshine hours". National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research. Archived from the original (XLS) on 15 October 2008. Retrieved 4 February 2011.

- ^ "New Zealand climate and weather". Tourism New Zealand. Archived from the original on 20 October 2016. Retrieved 13 November 2016.

- ^ "Climate data and activities". National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research. 28 February 2007. Archived from the original on 7 January 2019. Retrieved 11 February 2016.

- ^ Cooper, R.; Millener, P. (1993). "The New Zealand biota: Historical background and new research". Trends in Ecology & Evolution. 8 (12): 429–33. doi:10.1016/0169-5347(93)90004-9. PMID 21236222.

- ^ Trewick, S. A.; Morgan-Richards, M. (2014). New Zealand Wild Life. Penguin Books. ISBN 9780143568896.

- ^ Lindsey, Terence; Morris, Rod (2000). Collins Field Guide to New Zealand Wildlife. HarperCollins. p. 14. ISBN 978-1-86950-300-0.

- ^ McDowall, R. M. (2008). "Process and pattern in the biogeography of New Zealand – a global microcosm?". Journal of Biogeography. 35 (2): 197–212. Bibcode:2008JBiog..35..197M. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2699.2007.01830.x. ISSN 1365-2699. S2CID 83921062. Archived from the original on 18 August 2021. Retrieved 6 April 2021.

- ^ a b "Frequently asked questions about New Zealand plants". New Zealand Plant Conservation Network. May 2010. Archived from the original on 8 September 2012. Retrieved 15 January 2011.

- ^ De Lange, Peter James; Sawyer, John William David; Rolfe, Jeremy (2006). New Zealand Indigenous Vascular Plant Checklist. New Zealand Plant Conservation Network. ISBN 0-473-11306-6.

- ^ Wassilieff, Maggy (March 2009). "Lichens – Lichens in New Zealand". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Archived from the original on 17 January 2013. Retrieved 16 January 2011.

- ^ McLintock, Alexander, ed. (April 2010) [1966]. "Mixed Broadleaf Podocarp and Kauri Forest". An Encyclopaedia of New Zealand. Archived from the original on 17 January 2013. Retrieved 15 January 2011.

- ^ Mark, Alan (March 2009). "Grasslands – Tussock grasslands". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Archived from the original on 17 January 2013. Retrieved 17 January 2010.

- ^ "Commentary on Forest Policy in the Asia-Pacific Region (A Review for Indonesia, Malaysia, New Zealand, Papua New Guinea, Philippines, Thailand and Western Samoa)". Forestry Department. 1997. Archived from the original on 7 February 2019. Retrieved 4 February 2011.

- ^ McGlone, M. S. (1989). "The Polynesian settlement of New Zealand in relation to environmental and biotic changes" (PDF). New Zealand Journal of Ecology. 12(S): 115–129. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 July 2014.

- ^ Taylor, R.; Smith, I. (1997). The state of New Zealand's environment 1997 (Report). Wellington: New Zealand Ministry for the Environment. Archived from the original on 22 January 2015. Retrieved 6 March 2011.

- ^ "New Zealand ecology: Flightless birds". TerraNature. Archived from the original on 8 April 2020. Retrieved 17 January 2011.

- ^ a b Holdaway, Richard (March 2009). "Extinctions – New Zealand extinctions since human arrival". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Archived from the original on 20 January 2013. Retrieved 4 February 2011.

- ^ Kirby, Alex (January 2005). "Huge eagles 'dominated NZ skies'". BBC News. Archived from the original on 4 April 2023. Retrieved 4 February 2011.

- ^ "Reptiles and frogs". New Zealand Department of Conservation. Archived from the original on 29 January 2015. Retrieved 25 June 2017.

- ^ Pollard, Simon (September 2007). "Spiders and other arachnids". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Archived from the original on 6 June 2017. Retrieved 25 June 2017.

- ^ "Wētā". New Zealand Department of Conservation. Archived from the original on 12 June 2017. Retrieved 25 June 2017.

- ^ Ryan, Paddy (March 2009). "Snails and slugs – Flax snails, giant snails and veined slugs". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Archived from the original on 17 January 2013. Retrieved 4 February 2011.

- ^ Herrera-Flores, Jorge A.; Stubbs, Thomas L.; Benton, Michael J.; Ruta, Marcello (May 2017). "Macroevolutionary patterns in Rhynchocephalia: Is the tuatara (Sphenodon punctatus) a living fossil?". Palaeontology. 60 (3): 319–328. Bibcode:2017Palgy..60..319H. doi:10.1111/pala.12284.

- ^ "Tiny Bones Rewrite Textbooks, first New Zealand land mammal fossil". University of New South Wales. 31 May 2007. Archived from the original on 31 May 2007.