도널드 트럼프

Donald Trump도널드 트럼프 | |

|---|---|

공식초상화, 2017 | |

| 미국 제45대 대통령 | |

| 재직중 2017년 1월 20일 ~ 2021년 1월 20일 | |

| 부통령 | 마이크 펜스 |

| 선행후 | 버락 오바마 |

| 성공한 사람 | 조 바이든 |

| 개인내역 | |

| 태어난 | 도널드 존 트럼프 1946년 6월 14일 퀸즈, 뉴욕, 미국 |

| 정당 | 공화당 (1987-1999, 2009-2011, 2012-현재) |

| 기타정치 계열사 | |

| 배우자 | |

| 아이들. | |

| 친척들. | 도널드 트럼프의 가족 |

| 거주지 | 플로리다주 팜비치 마라라고 |

| 모교 | 펜실베이니아 대학교 (BS) |

| 직종. | |

| 시상식 | 풀리스트 |

| 서명 |  |

| 웹사이트 | |

| ||

|---|---|---|

| 업무 및 개인 재직기간 검찰 러시아와 관련된 상호작용  | ||

도널드 존 트럼프(Donald John Trump, 1946년 6월 14일 ~ )는 2017년부터 2021년까지 미국의 45대 대통령을 역임한 미국의 정치인, 언론인, 사업가입니다.

트럼프는 1968년에 펜실베니아 대학교에서 경제학 학사 학위를 받았고, 그의 아버지는 1971년에 그를 그의 부동산 사업 회장으로 임명했습니다. 트럼프는 회사 이름을 트럼프 조직으로 바꾸고 초고층 빌딩, 호텔, 카지노, 골프장 등을 짓고 개조하는 쪽으로 방향을 바꿨습니다. 20세기 후반 일련의 사업 실패 후, 그는 주로 트럼프 이름을 라이선스하는 것으로 적은 자본이 필요한 사이드 벤처를 성공적으로 시작했습니다. 2004년부터 2015년까지, 그는 리얼리티 텔레비전 시리즈 '어프렌티스(The Apprentice)'를 공동 제작하고 진행했습니다. 그와 그의 기업은 6건의 기업 파산을 포함하여 4,000건 이상의 주 및 연방 법률 소송에서 원고 또는 피고로 활동했습니다.

트럼프는 2016년 대선에서 민주당 힐러리 클린턴 후보를 상대로 공화당 후보로 나섰지만 국민투표에서 패배했습니다.[a] 선거 운동 기간 동안 그의 정치적 입장은 포퓰리즘, 보호주의, 고립주의, 민족주의자로 묘사되었습니다. 그의 당선과 정책은 수많은 시위를 촉발시켰습니다. 그는 군이나 정부의 경험이 전혀 없는 첫 미국 대통령이었습니다. 특검 조사 결과 러시아가 2016년 대선에서 트럼프의 선거운동에 유리하도록 개입한 것으로 드러났습니다. 트럼프는 선거운동과 대통령 재임 기간 동안 음모론을 조장하고 미국 정치에서 전례가 없을 정도로 많은 거짓과 오해의 소지가 있는 발언을 했습니다. 그의 많은 발언과 행동들은 인종적으로 비난받거나 인종차별적이고 많은 사람들이 여성 혐오적인 것으로 특징지어졌습니다.

트럼프는 대통령으로서 무슬림이 다수인 몇몇 국가의 시민들에 대한 여행 금지를 명령했고, 군사 자금을 미국에 장벽을 건설하는 쪽으로 전용했습니다.–멕시코 국경, 미국 국경에 억류된 이주민들에 대한 가족 분리 정책 시행 그는 환경 보호를 약화시켜 100개 이상의 환경 정책과 규제를 철회했습니다. 그는 개인과 기업에 대한 세금을 인하하고 건강보험 수가법의 개인 의료보험 수가 패널티를 폐지하는 2017년 감세 및 일자리 법에 서명했습니다. 그는 닐 고서치, 브렛 캐버노, 에이미 코니 배럿을 미국 대법원에 임명했습니다. 그는 코로나19 팬데믹에 천천히 대응하고, 보건 당국의 많은 권고를 무시하거나 반박하고, 검사 노력을 방해하기 위해 정치적 압력을 사용하고, 입증되지 않은 치료법에 대한 잘못된 정보를 퍼뜨렸습니다. 트럼프는 중국과 무역전쟁을 일으켜 환태평양경제동반자협정, 기후변화 파리협정, 이란 핵협상에서 미국을 탈퇴시켰습니다. 김정은을 세 번이나 만났지만 비핵화에는 진전이 없었습니다.

트럼프는 2020년 대선에서 조 바이든에게 패배한 후 양보를 거부하고 광범위한 선거 사기를 거짓으로 주장했으며, 정부 관리를 압박하고 실패한 법적 문제를 제기하고 대통령직 인수를 방해하여 결과를 뒤집으려고 시도했습니다. 2021년 1월 6일, 그는 지지자들에게 미국 의사당으로 행진할 것을 촉구했고, 그 후 많은 지지자들이 공격하여 다수의 사망자가 발생하고 선거인단 투표 집계를 중단했습니다.

트럼프는 두 번 탄핵당한 유일한 미국 대통령입니다. 2019년 우크라이나에 바이든을 조사하라고 압력을 넣으려 한 뒤, 그는 권력 남용과 의회 방해 혐의로 하원에서 탄핵당했습니다. 그는 2020년 2월 상원에서 무죄 판결을 받았습니다. 하원은 2021년 1월 반란 선동 혐의로 그를 다시 탄핵했습니다. 상원은 지난 2월 그에게 무죄를 선고했습니다. 학자들과 역사학자들은 트럼프를 미국 역사상 최악의 대통령 중 한 명으로 꼽습니다.[1][2]

트럼프는 퇴임 이후 공화당을 계속 장악하고 있으며 2024년 공화당 대선 예비선거 후보입니다. 2023년 민사 재판 배심원단은 트럼프가 E. 진 캐롤을 성적으로 학대했다는 사실을 밝혀냈습니다. 2024년, 뉴욕 주 법원은 트럼프가 금융 사기에 책임이 있다고 판결했습니다. 트럼프는 두 가지 판단에 모두 항소하고 있습니다. 그는 또한 뉴욕에서 34건의 업무 기록 위조 혐의로, 플로리다에서 40건의 기밀 문서를 잘못 처리한 것과 관련된 40건의 중범죄 혐의로, 2020년 대통령 선거를 뒤집으려는 노력에 대한 음모와 방해 혐의로 4건의 중범죄 혐의로 기소되었습니다. 그리고 조지아 주에서는 2020년 선거 결과를 뒤집기 위해 저지른 협박 및 기타 중범죄 혐의로 10명이 기소되었습니다. 트럼프는 모든 혐의에 대해 무죄를 주장했습니다.

사생활

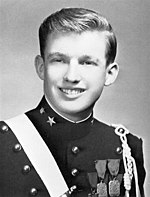

요절기

도널드 존 트럼프는 1946년 6월 14일 뉴욕 퀸즈의 자메이카 병원에서 프레드 트럼프와 메리 앤 맥리드 트럼프의 넷째 [3]아이로 태어났습니다. 트럼프는 퀸스의 자메이카 에스테이트 근처에서 형 메리앤, 프레드 주니어, 엘리자베스와 남동생 로버트와 함께 자랐고 유치원부터 7학년까지 사립 큐포레스트 스쿨을 다녔습니다.[4][5][6] 그는 13살에 사립 기숙학교인 뉴욕 육군사관학교에 입학했습니다.[7] 1964년, 그는 포덤 대학교에 입학했습니다. 2년 후, 그는 펜실베니아 대학교 와튼 스쿨로 편입하여 1968년 5월 경제학 학사로 졸업했습니다.[8][9] 2015년, 트럼프의 변호사 마이클 코언은 트럼프의 대학, 고등학교, 대학위원회가 트럼프의 학업 성적을 공개하면 법적 조치를 취하겠다고 위협했습니다.[10]

트럼프는 대학에 다니는 동안 베트남 전쟁 동안 네 번의 학생 징집 연기를 받았습니다.[11] 1966년 건강검진을 근거로 병역에 적합하다는 판정을 받았고, 1968년 7월 지방 징병위원회는 그를 병역 대상자로 분류했습니다.[12] 1968년 10월 조건부 의학적 유예인 1-Y로 분류됐고,[13] 1972년 뼈의 혹으로 4-F로 재분류돼 영구 결격 판정을 받았습니다.[14]

가족

1977년, 트럼프는 체코 모델 이바나 젤니치코바와 결혼했습니다.[15] 그들은 세 자녀를 두었습니다: 도널드 주니어 (1977년생), 이반카 (1981년생), 에릭 (1984년생). 이바나는 1988년에 귀화한 미국 시민이 되었습니다.[16] 이 부부는 1990년 트럼프가 여배우 말라 메이플스와 바람을 피운 후 이혼했습니다.[17] 트럼프와 메이플스는 1993년에 결혼했고 1999년에 이혼했습니다. 그들은 캘리포니아에서 말라에 의해 길러진 딸 티파니(1993년생)가 있습니다.[18] 2005년 트럼프는 슬로베니아 모델 멜라니아 크나우스와 결혼했습니다.[19] 그들에게는 아들 배런(2006년생)이 한 명 있습니다.[20] 멜라니아는 2006년에 미국 시민권을 얻었습니다.[21]

종교

트럼프는 주일학교에 다녔고 1959년 퀸즈 자메이카의 퍼스트 장로교회에서 확진 판정을 받았습니다.[22][23] 1970년대에 그의 부모님은 미국 개혁 교회에 속한 맨해튼의 마블 대학 교회에 들어갔습니다.[22][24] 마블의 Norman Vincent Peele 목사는 1993년 사망할 때까지 가족을 위해 목회를 했습니다.[22][24] 트럼프는 그를 멘토로 묘사했습니다.[25] 2015년, 교회는 트럼프가 현역 의원이 아니라고 밝혔습니다.[23] 2019년, 그는 자신의 개인 목사인 텔레비전 천사 폴라 화이트를 백악관 공공 연락 사무소에 임명했습니다.[26] 2020년, 그는 자신이 비종교적인 기독교인이라고 밝혔습니다.[27]

건강습관

트럼프는 골프를 자신의 "주요 운동 형태"라고 불렀지만 보통 코스를 걷지는 않습니다.[28] 그는 운동이 "배터리처럼, 한정된 양의 에너지로" 신체의 에너지를 고갈시킨다고 믿습니다.[29] 2015년, 트럼프의 선거 운동은 트럼프가 "대통령에 선출된 사람 중 가장 건강한 사람이 될 것"이라는 그의 오랜 개인 의사 해럴드 본스타인의 편지를 공개했습니다.[30] 2018년 본스타인은 트럼프가 편지의 내용을 지시했으며 2017년 2월 의사실에 대한 급습에서 트럼프 요원 3명이 그의 의료 기록을 압수했다고 말했습니다.[30][31]

재산

1982년 트럼프는 가족의 순자산 2억 달러(2023년 6억 3,100만 달러 상당)의 지분을 보유한 것으로 포브스의 초기 자산가 명단에 올랐습니다.[32] 1980년대에 그의 패배로 1990년과 1995년 사이에 그는 명단에서 빠졌습니다.[33] 2015년 7월 FEC에 의무적인 재무 공시 보고서를 제출한 후 약 100억 달러의 순자산을 발표했습니다. FEC가 발표한 기록에 따르면 최소 14억 달러의 자산과 2억 6천 5백만 달러의 부채가 있는 것으로 나타났습니다.[34] 포브스는 2015년과 2018년 사이에 그의 순자산이 14억 달러 감소했다고 추정했습니다.[35] 2023년 억만장자 순위에서 트럼프의 순자산은 25억 달러(세계 1,217위)로 추정됐습니다.[36]

저널리스트 조나단 그린버그는 트럼프가 1984년 '존 배런'이라는 가상의 트럼프 조직 관계자인 척 자신에게 전화를 걸었다고 보도했습니다. 그린버그는 트럼프가 '배런'이라고 말하면서 포브스 400대 미국인 부자 순위에서 더 높은 순위를 얻기 위해 아버지 사업의 90% 이상을 소유했다고 거짓 주장했다고 말했습니다. 그린버그는 또한 포브스가 트럼프의 재산을 엄청나게 과대평가했고 1982년, 1983년, 1984년 순위에 그를 잘못 포함시켰다고 썼습니다.[37]

트럼프는 아버지로부터 받은 "100만 달러의 소액 대출"로 선수 생활을 시작했으며, 이자로 갚아야 한다고 종종 말해왔습니다.[38] 그는 8살 때 백만장자였고, 그의 아버지로부터 적어도 6천만 달러를 빌렸고, 대부분 그 대출들을 갚지 못했고, 그의 아버지의 회사로부터 4억 1천 3백만 달러(2018년 인플레이션 조정)를 더 받았습니다.[39][40] 2018년에 그와 그의 가족이 세금 사기를 저질렀다는 보고를 받았고, 뉴욕 주 조세 재정부가 조사에 착수했습니다.[40] 그의 투자는 주식과 뉴욕 부동산 시장을 과소평가했습니다.[41][42] 포브스는 2018년 10월 순자산이 2015년 45억 달러에서 2017년 31억 달러로, 제품 라이선스 수입이 2,300만 달러에서 300만 달러로 감소했다고 추정했습니다.[43]

재정 건전성과 사업 수완에 대한 그의 주장과는 달리, 1985년부터 1994년까지 트럼프의 세금 신고는 총 11억 7천만 달러의 순손실을 보여줍니다. 손실은 거의 모든 미국 납세자의 손실보다 높았습니다. 1990년과 1991년의 손실은 매년 2억 5천만 달러 이상으로 가장 가까운 납세자의 두 배 이상이었습니다. 1995년, 그의 보고된 손실은 9억 1,570만 달러 (2023년 18억 3,[44][45][32]000만 달러에 해당)였습니다.

2020년, 뉴욕 타임즈는 20년에 걸쳐 연장되는 트럼프의 세금 정보를 입수했습니다. 기자들은 트럼프가 수억 달러의 손실을 보고했고, 2010년 이후 2억 8,700만 달러의 용서된 부채를 과세 소득으로 신고하는 것을 연기했다고 밝혔습니다. 그의 수입은 주로 그가 소수 파트너였던 견습생과 사업에 대한 그의 몫에서 비롯되었고, 그의 손실은 주로 다수 소유의 사업에서 비롯되었습니다. 많은 수입이 그의 손실에 대한 세금 공제로 이루어졌고, 이로 인해 그는 연간 소득세 납부를 피하거나 750달러로 낮출 수 있었습니다. 트럼프는 2010년대에 1억 달러의 트럼프 타워 모기지(2022년 만기)와 2억 달러가 넘는 주식 및 채권 청산을 포함하여 자산 대비 매도 및 차입을 통해 기업의 손실을 균형 있게 처리했습니다. 그는 개인적으로 4억 2,100만 달러의 부채를 보장했는데, 대부분의 부채는 2024년까지 만기입니다.[46]

2021년[update] 10월 현재 트럼프는 13억 달러가 넘는 부채를 가지고 있으며, 이 중 상당 부분을 자산으로 확보하고 있습니다.[47] 그는 2020년 중국은행, 도이치뱅크, UBS 등 은행과 신탁기관에 6억 4천만 달러, 알려지지 않은 채권자들에게 약 4억 5천만 달러의 빚을 졌습니다. 그의 자산 가치는 그의 부채를 초과합니다.[48]

사업경력

부동산

1968년부터 트럼프는 뉴욕시 외곽 자치구에 인종적으로 분리된 중산층 임대 주택을 소유하고 있는 아버지의 부동산 회사인 트럼프 매니지먼트에 고용되었습니다.[49][50] 1971년, 그는 회사의 사장이 되었고 트럼프 조직을 우산 브랜드로 사용하기 시작했습니다.[51] 1991년부터 2009년 사이에 그는 맨해튼의 플라자 호텔, 뉴저지주 애틀랜틱 시티의 카지노, 트럼프 호텔 & 카지노 리조트 회사 등 6개 사업에 대해 파산 보호를 신청했습니다.[52]

맨해튼 개발.

트럼프는 1978년 가족의 첫 맨해튼 벤처인 그랜드 센트럴 터미널과 인접한 버려진 코모도어 호텔의 개조를 시작하면서 대중의 관심을 끌었습니다.[53] 이 자금 조달은 하얏트와 공동으로 7천만 달러의 은행 건설 대출을 보증한 그의 아버지가 트럼프를 위해 마련한 4억 달러의 도시 재산세 감면에 의해 촉진되었습니다.[50][54] 이 호텔은 1980년 그랜드 하얏트 호텔로 다시 문을 열었고,[55] 같은 해 트럼프는 맨해튼 미드타운에 있는 주상복합 마천루인 트럼프 타워 개발권을 획득했습니다.[56] 이 건물에는 트럼프 코퍼레이션과 트럼프 PAC의 본사가 있으며 2019년까지 트럼프의 주요 거주지였습니다.[57][58]

1988년 트럼프는 16개 은행 컨소시엄으로부터 대출을 받아 플라자 호텔을 인수했습니다.[59] 호텔은 1992년 파산보호신청을 했고, 한 달 뒤 은행들이 부동산을 장악하는 내용의 조직재편계획이 승인됐습니다.[60] 1995년, 트럼프는 30억 달러가 넘는 은행 대출을 불이행했고, 대출 기관들은 굴욕적인 구조조정으로 플라자 호텔과 그의 다른 부동산 대부분을 압류했습니다.[61][62] 이 은행의 변호사는 은행들의 결정에 대해 "그가 죽는 것보다 살아있는 것이 낫다는 데 모두 동의했다"고 말했습니다.[62]

1996년, 트럼프는 대부분 비어있는 월스트리트 40번지의 71층짜리 고층 건물을 인수하고 개조했으며, 나중에 트럼프 빌딩으로 브랜드를 바꿨습니다.[63] 1990년대 초, 트럼프는 허드슨 강 근처 링컨 광장 인근에 70에이커(28ha) 규모의 트랙 개발권을 따냈습니다. 1994년 다른 벤처 기업들의 부채로 어려움을 겪던 트럼프는 프로젝트에 대한 대부분의 관심을 아시아 투자자들에게 팔았고, 아시아 투자자들은 프로젝트의 완공을 위해 자금을 조달했습니다.[64]

애틀랜틱 시티 카지노

1984년 트럼프는 홀리데이 코퍼레이션의 자금 조달 및 관리 도움을 받아 호텔 및 카지노인 트럼프 플라자에 Harah's를 열었습니다.[65] 그것은 수익성이 없었고, 트럼프는 1986년 5월 홀리데이에 7천만 달러를 지불하여 독점권을 장악했습니다.[66] 1985년, 트럼프는 개장하지 않은 애틀랜틱 시티 힐튼 호텔을 사들여 트럼프 캐슬로 이름을 바꿨습니다.[67] 그의 아내 이바나가 1988년까지 그것을 관리했습니다.[68] 두 카지노 모두 1992년 파산보호 신청을 했습니다.[69]

트럼프는 1988년에 세 번째 대서양 도시 장소인 트럼프 타지마할을 구입했습니다. 6억 7천 5백만 달러의 정크본드로 자금을 조달하였고, 1990년 4월에 개장하여 11억 달러에 완공하였습니다.[70][71] 트럼프는 1991년 파산보호를 신청했습니다. 구조조정 합의 조항에 따라 트럼프는 초기 지분의 절반을 포기하고 개인적으로 미래 성과를 보장했습니다.[72] 9억 달러의 개인 빚을 줄이기 위해 그는 트럼프 셔틀 항공사; 카지노에 임대되어 계속 정박해 있던 그의 메가요트, 트럼프 프린세스; 그리고 다른 사업들을 팔았습니다.[73]

1995년 트럼프는 트럼프 플라자의 소유권을 인수한 트럼프 호텔 & 카지노 리조트(THCR)를 설립했습니다.[74] THCR은 1996년 타지마할과 트럼프 성을 매입했고 2004년과 2009년 파산해 트럼프가 10%의 소유권을 갖게 됐습니다.[65] 그는 2009년까지 회장직을 유지했습니다.[75]

클럽

1985년 트럼프는 플로리다 팜비치에 있는 마라라고 사유지를 인수했습니다.[76] 1995년, 그는 그 사유지를 개인 클럽으로 전환했고, 가입비와 연회비를 지불했습니다. 그는 집의 날개를 사저로 계속 사용했습니다.[77] 트럼프는 2019년에 클럽을 주요 거주지로 선언했고,[58] 2021년에 마을은 그가 클럽의 직원으로 합법적으로 거주할 자격이 있다고 결정했습니다.[58][78][importance?] 트럼프 기구는 1999년부터 골프장을 짓고 구입하기 시작했습니다.[79] 14개를 소유하고 있으며 전 세계적으로 트럼프 브랜드 코스 3개를 관리하고 있습니다.[79][80]

트럼프 브랜드 라이선스

트럼프 이름은 식품, 의류, 학습 과정 및 홈퍼니싱을 포함한 소비자 제품 및 서비스에 대한 라이선스를 받았습니다.[81][82] 워싱턴포스트에 따르면 트럼프의 이름과 관련된 인허가나 관리 거래는 50건이 넘으며, 이로 인해 트럼프의 기업들은 최소 5,900만 달러의 수익을 올렸다고 합니다.[83] 2018년까지 단 두 개의 소비재 회사만이 그의 이름을 계속 라이선스했습니다.[81]

사이드 벤처스

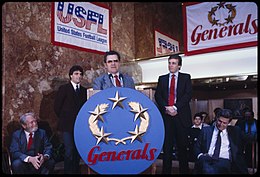

1983년 9월, 트럼프는 미국 풋볼 리그의 한 팀인 뉴저지 제너럴스를 인수했습니다. 1985년 시즌 이후 리그가 접힌 것은 주로 (NFL과 관중 경쟁을 벌였을 때) 가을 일정으로 경기를 옮기고, NFL을 상대로 반독점 소송을 제기하여 NFL과 합병을 강요하려는 트럼프의 전략 때문입니다.[84][85]

트럼프와 그의 플라자 호텔은 애틀랜틱 시티 컨벤션 홀에서 여러 차례 복싱 경기를 개최했습니다.[65][86] 1989년과 1990년에 트럼프는 투르 드 프랑스나 지로 이탈리아와 같은 유럽 경주와 동등한 미국 경주를 만들기 위해 투르 드 트럼프 사이클 무대 경주에 자신의 이름을 빌려주었습니다.[87]

1986년부터 1988년까지 트럼프는 회사를 인수할 의도가 있다고 제안하면서 다양한 공개 회사의 상당한 주식 블록을 매입한 다음 이익을 위해 주식을 매각하여 [44]일부 관측통들은 그가 그린메일에 종사하고 있다고 생각했습니다.[88] 뉴욕타임스는 트럼프가 처음에는 이런 주식 거래로 수백만 달러를 벌었지만 "투자자들이 그의 인수를 심각하게 받아들이지 않은 후 전부는 아니더라도 대부분의 이익을 잃었다"고 전했습니다.[44]

1988년 트럼프는 이스턴 에어라인 셔틀을 구입하여 22개 은행으로 구성된 신디케이트로부터 3억 8천만 달러([32]2023년 9억 7천 9백만 달러에 해당)의 대출을 받아 구매 자금을 조달했습니다. 그는 항공사 이름을 트럼프 셔틀(Trump Shuttle)로 바꾸고 1992년까지 운영했습니다.[89] 트럼프는 1991년 대출을 불이행했고, 소유권은 은행으로 넘어갔습니다.[90]

1992년 트럼프와 그의 형제자매 메리앤, 엘리자베스, 로버트, 그리고 사촌 존 W. 월터가 각각 20%의 지분을 가지고 올 카운티 빌딩 공급 및 유지보수 공사를 설립했습니다. 이 회사는 사무실이 없었고 트럼프의 임대 유닛에 대한 서비스와 공급품을 제공하는 공급업체에 지불한 후 20~50% 이상의 인상률로 트럼프 경영진에 해당 서비스와 공급품을 청구한 쉘 회사였다고 주장됩니다. 소유자는 마크업으로 발생한 수익을 공유했습니다.[40][91] 늘어난 비용은 트럼프의 임대료 안정화 사업부의 임대료 인상에 대한 주 정부의 승인을 받는 데 사용되었습니다.[40]

1996년부터 2015년까지 트럼프는 미스 USA와 미스 틴 USA를 포함한 미스 유니버스 페이지의 전부 또는 일부를 소유했습니다.[92][93] 그는 CBS와의 스케줄에 대한 의견 차이로 2002년에 두 페이지언트를 모두 NBC로 데려갔습니다.[94][95] 2007년, 트럼프는 미스 유니버스의 제작자로서의 일로 할리우드 명예의 거리에서 별을 받았습니다.[96] NBC와 Univision은 2015년 6월에 페이지언트를 중단했습니다.[97]

트럼프 대학교

2004년, 트럼프는 부동산 세미나를 최대 3만 5천[excessive detail?] 달러에 판매한 회사인 트럼프 대학을 공동 설립했습니다.[98] 뉴욕주 당국이 "대학" 사용이 주법을 위반했다고 통보한 후(학문 기관이 아니기 때문에), 2010년에 트럼프 기업가 이니셔티브(Trump Enterpreneur Initiative)로 이름이 변경되었습니다.[99]

2013년, 뉴욕주는 트럼프 대학이 거짓 진술을 하고 소비자들을 편취했다며 트럼프 대학을 상대로 4천만 달러의 민사 소송을 제기했습니다.[100] 또 트럼프와 그의 회사들을 상대로 연방법원에 두 건의 집단소송이 제기됐습니다. 내부 문건에는 직원들에게 강매 방식을 쓰라는 지시가 내려졌고, 전직 직원들은 트럼프 대학이 학생들에게 편취하거나 거짓말을 했다고 증언했습니다.[101][102][103] 2016년 대선에서 승리한 직후, 트럼프는 세 사건을 해결하기 위해 총 2,500만 달러를 지불하기로 합의했습니다.[104]

토대

도널드 J. 트럼프 재단은 1988년에 설립된 민간 재단입니다.[105][106] 1987년부터 2006년까지 트럼프는 2006년 말까지 사용된 540만 달러를 자신의 재단에 기부했습니다. 2007-2008년 총 65,000달러를 기부한 후, 그는 빈스 맥마흔으로부터 500만 달러를 포함하여 다른 기부자들로부터 수백만 달러를 받은 자선 단체에 개인적인 자금을 기부하는 것을 중단했습니다.[107][108] 이 재단은 건강 및 스포츠 관련 자선 단체, 보수 단체 [109]및 트럼프 재산에서 행사를 개최한 자선 단체에 기부했습니다.[107]

2016년 워싱턴 포스트는 자선단체가 자기 거래 혐의와 탈세 가능성을 포함하여 몇 가지 잠재적인 법적, 윤리적 위반을 저질렀다고 보도했습니다.[110] 또한 2016년 뉴욕 검찰총장은 매년 외부감사에 제출하지 않고 기부를 권유한 재단을 주법 위반으로 판단하고 뉴욕에서의 모금 활동을 즉시 중단하도록 명령했습니다.[111] 트럼프 팀은 2016년 12월 재단이 해산될 것이라고 발표했습니다.[112]

2018년 6월, 뉴욕 법무장관실은 재단과 트럼프, 그리고 그의 성인 자녀들을 상대로 280만 달러의 배상금과 추가 벌금을 요구하는 민사 소송을 제기했습니다.[113] 2018년 12월, 재단은 운영을 중단하고 자산을 다른 자선단체에 지출했습니다.[114] 2019년 11월, 뉴욕 주 판사는 트럼프에게 자신의 대선 캠페인 자금을 마련하기 위해 재단의 자금을 유용한 자선 단체에 200만 달러를 지불하라고 명령했습니다.[115][116]

법무 및 파산

로이 콘은 1970년대와 1980년대에 13년 동안 트럼프의 해결사, 변호사, 멘토였습니다.[117] 트럼프에 따르면 콘은 때때로 그들의 우정 때문에 수수료를 면제했습니다.[117] 1973년 콘은 트럼프의 재산이 인종 차별적 관행을 가지고 있다는 혐의로 미국 정부에 1억 달러([32]2023년 6억8600만 달러 상당)를 청구하는 데 도움을 주었습니다. 트럼프 측의 반론은 기각됐고, 정부의 소송이 진행돼 결국 타결로 이어졌습니다.[118] 1975년, 트럼프의 부동산이 뉴욕 도시 연맹에 2년 동안 매주 모든 아파트 공실 목록을 제공하도록 의무화하는 합의가 이루어졌습니다.[119] 콘은 연방 정부를 상대하기 위해 스톤의 서비스를 요청한 트럼프에게 정치 컨설턴트 로저 스톤을 소개했습니다.[120]

USA 투데이가 2018년에 실시한 주 및 연방 법원 파일 검토에 따르면 트럼프와 그의 기업은 4,000건 이상의 주 및 연방 법률 소송에 관여했습니다.[121] 트럼프는 개인 파산을 신청하지 않았지만 애틀랜틱시티와 뉴욕에서 과도하게 레버리지를 가진 호텔과 카지노 사업체는 1991년부터 2009년까지 6차례에 걸쳐 파산보호를 신청했습니다.[122] 그들은 은행들이 부채를 재조정하고 부동산에 대한 트럼프의 지분을 줄이는 동안 계속 운영되었습니다.[122]

1980년대 동안 70개 이상의 은행이 트럼프에게 40억 달러를 대출했습니다.[123] 1990년대 초 그의 기업 파산 이후, 도이체방크를 제외한 대부분의 주요 은행들은 그에게 대출을 거절했습니다.[124] 1월 6일 국회의사당 공격 이후, 은행은 앞으로 트럼프나 그의 회사와 거래하지 않기로 결정했습니다.[125]

미디어 커리어

책들

대필가를 사용하여 트럼프는 자신의 이름으로 비즈니스, 금융 또는 정치적 주제에 대한 최대 19권의 책을 제작했습니다.[126] 그의 첫 번째 책, The Art of the Deal (1987)은 뉴욕 타임즈 베스트 셀러였습니다. 트럼프가 공저자로 인정받았지만, 전체 책은 토니 슈워츠가 썼습니다.[127] The New Yorker에 따르면, "이 책은 트럼프의 명성을 뉴욕시를 훨씬 넘어 확장시켰고, 그를 성공한 거물의 상징으로 만들었습니다."[127] 트럼프는 이 책을 성경 다음으로 두 번째로 좋아하는 책이라고 불렀습니다.[128]

영화와 텔레비전

트럼프는 1985년부터 2001년까지 많은 영화와 텔레비전 쇼에 카메오로 출연했습니다.[129]

트럼프는 1980년대 후반부터 프로레슬링 프로모션 WWE와 산발적으로 관계를 맺었습니다.[130] 그는 2007년 레슬매니아 23에 출연했고, 2013년 WWE 명예의 전당의 연예인 윙에 헌액되었습니다.[131]

1990년대를 시작으로 트럼프는 전국적으로 연합된 하워드 스턴 쇼에 약 24번 게스트로 출연했습니다.[132] 그는 또한 2004년부터 2008년까지 Trumped! (평일 1~2분)라는 짧은 형식의 토크 라디오 프로그램을 운영했습니다.[133][134] 2011년부터 2015년까지 폭스 & 프렌즈에서 매주 무급 객원 해설자로 활동했습니다.[135][136]

2004년부터 2015년까지 트럼프는 리얼리티 쇼 '어프렌티스'와 '연예인 어프렌티스'의 공동 제작자이자 진행자였습니다. 트럼프는 "당신은 해고입니다"라는 캐치프레이즈로 참가자들을 탈락시킨 초부자이자 성공한 최고경영자로서 자신을 칭찬하고 매우 허구화한 버전을 연기했습니다. 그 쇼는 전국의 수백만 명의 시청자들에게 그의 이미지를 다시 만들었습니다.[137][138] 관련 라이선스 계약으로 그는 수익성이 낮은 사업에 투자한 4억 달러 이상을 벌었습니다.[139]

2021년 2월, 트럼프는 2021년 1월 6일 선동, 미국 국회의사당에 대한 폭도 공격, "신임을 떨어뜨리고 궁극적으로 언론인의 안전을 위협하기 위한 무모한 잘못된 정보 캠페인"으로 인해 징계위원회 청문회에 직면하지 않고 1989년부터 회원으로 있던 스크린 배우 조합에서 사임했습니다.[140] 이틀 후, 노조는 그의 재입학을 영구적으로 금지했습니다.[141]

정치경력

트럼프의 정당 소속은 여러 번 바뀌었습니다. 1987년 공화당,[142] 1999년 개혁당의 뉴욕 주 계열 독립당 의원,[143] 2001년 민주당, 2009년 공화당, 2011년 무소속, 2012년 공화당 의원으로 등록했습니다.[142]

1987년 트럼프는 3대 신문에 전면광고를 [144]내면서 외교정책과 연방정부 재정적자 해소 방안에 대한 자신의 견해를 밝혔습니다.[145] 그는 지방선거 출마는 배제했지만 대통령 출마는 배제했습니다.[144] 1988년, 그는 공화당 후보 조지 H. W. 부시의 러닝메이트가 될 것을 고려해달라고 리 애트워터에게 접근했습니다. 부시 대통령은 이 요청을 "이상하고 믿을 수 없다"고 생각했습니다.[146]

대통령 선거운동 (2000년~2016년)

2000년, 트럼프는 캘리포니아와 미시간의 예비선거에서 2000년 대선의 개혁당 후보로 지명되기 위해 출마했지만, 2000년 2월에 경선에서 물러났습니다.[147][148][149] 1999년 7월 공화당 후보 조지 W. 부시와 민주당 후보 앨 고어를 상대로 한 여론조사에서 트럼프는 7%의 지지를 받았습니다.[150]

2011년, 트럼프는 2012년 대선에서 버락 오바마 대통령을 상대로 출마할 것을 추측했고, 2011년 2월 보수 정치 행동 회의 (CPAC)에 처음으로 연설을 하고 초기 예비 주에서 연설을 했습니다.[151][152] 2011년 5월, 그는 불출마를 선언했습니다.[151] 당시 트럼프의 대선 야망은 일반적으로 심각하게 받아들여지지 않았습니다.[153]

2016년 대선

트럼프의 명성과 자극적인 발언은 전례 없이 많은 양의 무료 언론 보도를 이끌어내며 공화당 예비선거에서 그의 입지를 높였습니다.[154] 그는 자신의 대중 연설 스타일을 묘사하기 위해 대필가 토니 슈워츠에 의해 만들어진 "진실한 하이퍼볼"이라는 문구를 채택했습니다.[127][155] 그의 선거운동 성명은 종종 불투명하고 암시적이었고,[156] 그 중 기록적인 숫자는 거짓이었습니다.[157][158][159] 로스앤젤레스타임스는 "현대 대선 정치에서 주요 후보가 트럼프처럼 일상적으로 거짓 발언을 한 적이 없다"고 썼습니다.[160][161] 트럼프는 정치적 올바름을 경멸하고 언론 편향 주장을 자주 했다고 말했습니다.[162][163]

트럼프는 2015년 6월 출마를 선언했습니다.[164][165] 그의 선거운동은 정치 분석가들에 의해 처음에는 심각하게 받아들여지지 않았지만, 그는 빠르게 여론조사에서 1위로 올라섰습니다.[166] 그는 2016년[167] 3월 선두주자가 됐고, 5월 공화당 추정 후보로 선언됐습니다.[168]

힐러리 클린턴은 선거운동 기간 내내 전국 평균 여론조사에서 트럼프를 앞섰지만, 7월 초에는 선두가 좁혀졌습니다.[169][170] 지난 7월 중순 트럼프는 마이크 펜스 인디애나 주지사를 부통령 러닝메이트로 선정했고,[171] 이 둘은 2016년 공화당 전당대회에서 공식 지명됐습니다.[172] 트럼프와 클린턴은 2016년 9월과 10월 세 차례 대선 토론에서 맞붙었습니다. 트럼프는 선거 결과에 승복할지에 대해 두 차례나 말을 아꼈습니다.[173]

선거운동 수사학과 정치적 입장

트럼프의 정치적 입장과 수사학은 우파 포퓰리즘이었습니다.[174][175][176] 폴리티코는 미국 기업 연구소의 의료 정책 전문가의 말을 인용해 자신의 정치적 입장이 "공개적으로 연주하는 모든 것의 완전한 무작위 모음"이라고 말했습니다.[177] NBC 뉴스는 그의 선거운동 기간 동안 "23개의 주요 이슈에 대한 141개의 뚜렷한 변화"를 집계했습니다.[178]

트럼프는 나토의 필요성에 의문을 제기하며 비개입주의자와 보호주의자로 묘사되는 견해를 지지했습니다.[179] 그의 선거 공약은 미국의 재협상을 강조했습니다.– NAFTA, 환태평양경제동반자협정 등 중국관계와 자유무역협정(FTA), 이민법의 강력한 집행, 미국을 따라 새로운 장벽 건설.–멕시코 국경. 그 밖에 청정전력계획, 파리협정 등 기후변화 규제에 반대하면서 에너지 자립을 추구하는 것, 참전용사를 위한 서비스 현대화 및 신속화, 부담가능돌봄법 폐지 및 대체, 공통핵심교육기준 폐지, 인프라 투자, 모든 경제 계층의 세금을 줄이는 동시에 세법을 간소화하고, 일자리를 제외한 회사의 수입품에 관세를 부과합니다. 그는 군사비 지출을 늘리고, 국내 이슬람 테러를 사전에 차단하기 위해 무슬림이 다수인 국가에서[180] 온 이민자들을 극단적으로 조사하거나 금지하는 한편, 이라크와 레반트 이슬람 국가에 대한 공격적인 군사 행동을 하는 한편, 외교 정책에 대한 대부분의 비개입주의적 접근을 주장했습니다. 그는 나토를 "낡은 것"이라고 묘사했습니다.[181][182]

트럼프는 극우 변방 사상, 신념, 조직을 주류로 끌어들이는 데 도움을 주었습니다.[183] 트럼프는 2016년 2월 28일 CNN 인터뷰에서 데이비드 듀크의 지지에 대한 질문을 받은 후 천천히 거절했습니다.[184] 듀크는 트럼프를 열렬히 지지하며 자신과 마음이 맞는 사람들이 "우리나라를 되찾겠다"는 트럼프의 약속 때문에 트럼프에게 표를 던졌다고 말했습니다.[185][186] 2016년 8월, 트럼프는 "알트우파를 위한 플랫폼"으로 묘사한 브라이트바트 뉴스의 스티브 배넌 집행위원장을 선거운동 CEO로 고용했습니다.[187] 중도 우파 운동은 다문화주의와 이민에 대한 부분적인 반대 때문에 연합하여 트럼프의 출마를 지지했습니다.[188][189][190]

재무공시

트럼프의 FEC 요구 보고서에는 14억 달러 이상의 자산과 최소 3억 1,500만 달러의 미결제 부채가 기재되어 있습니다.[34][191] 트럼프는 1976년 이후 모든 주요 후보자들의 관행과 2014년과 2015년 대선에 출마할 경우 세금 신고서를 공개하지 않았습니다.[192][193] 그는 세금 신고서가 감사를 받고 있으며 변호사들이 세금 신고서를 공개하지 말라고 조언했다고 말했습니다.[194] 트럼프가 미국 대법원에 두 차례 항소한 것을 포함해 범죄 수사를 위해 맨해튼 지방 검사에게 제출한 세금 신고서 및 기타 기록의 공개를 막기 위한 오랜 법정 투쟁 끝에 2021년 2월 고등법원은 대배심의 검토를 위해 기록을 검사에게 공개할 수 있도록 허용했습니다.[195][196]

2016년 10월, 1995년 트럼프의 국정 서류의 일부가 뉴욕 타임즈의 기자에게 유출되었습니다. 트럼프가 그해 9억1600만 달러의 손실을 선언해 최대 18년 동안 세금을 피할 수 있었다는 것을 보여줍니다.[197]

대통령 선거

2016년 11월 8일, 트럼프는 306명의 공약 선거인단 투표 대 232명의 클린턴을 얻었지만, 양측의 선거인단 이탈 이후 공식 집계는 결국 304명 대 227명이었습니다.[198] 국민투표에서 패배하면서 다섯 번째로 대통령에 당선된 트럼프는 클린턴보다 거의 290만 표를 덜 받았습니다.[199] 그는 또한 대통령이 되기 전에 군 복무를 하지도 않았고 정부 직책을 맡지도 않은 유일한 대통령이었습니다.[200] 트럼프의 승리는 정치적으로 큰 충격을 주었습니다.[201] 여론조사 결과 클린턴은 전국적으로 우세한 것은 물론 대부분의 경쟁주에서 우세한 것으로 나타났습니다. 트럼프의 지지도는 다소 과소평가된 반면 클린턴은 과대평가된 것으로 나타났습니다.[202]

트럼프는 1990년대부터 민주당 텃밭의 블루월로 여겨졌던 미시간, 펜실베이니아, 위스콘신 등 30개 주에서 승리했습니다. 클린턴은 20개 주와 컬럼비아 특별구에서 승리했습니다. 트럼프의 승리는 분열되지 않은 공화당 정부, 즉 공화당이 의회 양원을 장악한 백악관의 귀환을 의미했습니다.[203]

트럼프의 선거 승리는 선거 다음 날 미국 주요 도시에서 시위를 촉발시켰습니다.[204][205] 트럼프가 취임한 다음 날 워싱턴DC에서 50만 명으로 추정되는 사람들을 포함해 전 세계적으로 260만 명으로 추산되는 사람들이 여성 행진에서 트럼프에 반대하는 시위를 벌였습니다.[206]

사장 (2017년~2021년)

초기조치

트럼프는 2017년 1월 20일에 취임했습니다. 취임 첫 주 동안, 그는 여섯 개의 행정 명령에 서명했는데, 이 명령은 건강보험법("Obamacare")의 폐지를 기대하는 임시 절차, 환태평양경제동반자협정(TPP) 협상 탈퇴, 멕시코 시 정책의 복원, 키스톤 XL 및 다코타 액세스 파이프라인 건설 프로젝트의 발전, 국경 보안 강화, 멕시코와의 미국 국경을 따라 장벽을 건설하는 계획 및 설계 프로세스.[207]

트럼프의 딸 이방카와 사위 재러드 쿠슈너가 각각 보좌관과 선임고문이 됐습니다.[208][209]

이해상충

취임하기 전, 트럼프는 그의 사업을 그의 아들인 에릭과 도널드 주니어와 사업 동료가 운영하는 취소 가능한 신탁회사로 옮겼습니다.[210][211] 그는 "새로운 대외 거래"를 피하겠다고 말했지만, 트럼프 조직은 두바이, 스코틀랜드, 도미니카 공화국에서의 사업 확장을 추구했습니다. 트럼프는 자신의 사업에서 계속 이익을 얻었으며, 자신의 행정부의 정책이 자신의 사업에 어떤 영향을 미쳤는지 알고 있었습니다.[211][212]

그는 미국 헌법의 국내외 연금 조항을 위반한 혐의로 소송을 당했는데, 이 조항이 실질적으로 소송을 제기한 것은 처음입니다.[213] 1건은 원심에서 기각되었습니다.[214] 두 명은 트럼프 임기가 끝난 뒤 미 연방대법원에서 무뚝뚝하다고 기각됐습니다.[215]

트럼프는 대통령 재임 기간 1461일 중 428일(약 3분의 1) 트럼프 조직의 부동산을 방문해 5.6일에 한 번씩 261라운드의 골프를 친 것으로 추정됩니다.[216]

국내정책

경제.

트럼프는 2009년 6월부터 시작해 코로나19 경기침체가 시작된 2020년 2월까지 이어진 [217]미국 역사상 가장 긴 경제 확장의 정점에 취임했습니다.[218]

2017년 12월, 트럼프는 2017년 감세 및 일자리 법안에 서명했습니다. 이 법안은 공화당이 장악한 의회 양원에서 민주당 표 없이 통과되었습니다. 사업자와 개인에 대한 세율을 인하하고 영구적이고 개인별 감세는 2025년 이후 만료될 예정이며, 부담 가능한 돌봄법의 개인별 의무와 관련된 벌칙을 없앴습니다.[219][220] 트럼프 행정부는 이 같은 조치가 세수를 늘리거나 경제 성장을 촉진해 스스로 비용을 지불할 것이라고 주장했습니다. 대신 2018년 매출은 예상보다 7.6% 감소했습니다.[221]

8년 안에 국가 부채를 없애겠다는 선거 공약에도 불구하고, 트럼프는 정부 지출의 큰 폭의 증가와 2017년 감세를 승인했습니다. 그 결과, 연방 재정 적자는 거의 50% 증가하여 2019년에는 거의 1조 달러에 달했습니다.[222] 트럼프 대통령 시절 미국의 국가채무는 39% 증가해 임기 말까지 27조7천500억 달러에 달했고, GDP 대비 미국의 부채비율은 2차 세계대전 이후 최고치를 기록했습니다.[223] 트럼프는 선거운동을 했던 1조 달러의 인프라 지출 계획도 전달하지 못했습니다.[224]

트럼프는 취임 당시보다 300만 명 정도 적은 인력으로 퇴임한 유일한 현대 미국 대통령입니다.[217]

기후변화, 환경, 에너지

트럼프,[225][226] 기후변화에 대한 과학적 합의 거부 그는 재생에너지 연구 예산을 40% 줄였고 기후 변화를 억제하기 위한 오바마 시대의 정책을 뒤집었습니다.[227] 2017년 6월, 트럼프는 미국의 파리 협정 탈퇴를 발표했고, 미국은 협정을 비준하지 않은 유일한 국가가 되었습니다.[228]

트럼프는 화석 연료의 생산과 수출을 늘리는 것을 목표로 삼았습니다.[229][230] 트럼프 정권에서 천연가스는 팽창했지만 석탄은 계속 감소했습니다.[231][232] 트럼프는 온실가스 배출, 대기 및 수질 오염, 독성 물질 사용을 억제하는 것을 포함한 100개 이상의 연방 환경 규제를 철회했습니다. 그는 동물에 대한 보호와 연방 인프라 프로젝트에 대한 환경 기준을 약화시켰고, 북극 피난처에서 시추를 허용하는 등 시추 및 자원 추출을 위한 허용 지역을 확대했습니다. 트럼프 대통령의 대통령 시절 행보는 "우리 법을 다시 쓰고 환경 보호의 의미를 재해석하려는 매우 적극적인 시도"라고 불립니다.[233]

규제완화

2017년 1월 트럼프는 행정명령 13771에 서명했는데, 이는 모든 새로운 규정에 대해 연방 기관이 제거를 요구하지는 않지만 제거를 위한 두 가지 기존 규정을 "식별"하도록 지시했습니다.[234] 그는 다른 주제들 [238][236]중에서도 건강,[235][236] 노동,[237][236] 그리고 환경에 대한 많은 연방 규정들을 해체했습니다. 트럼프는 중증 정신질환자의 총기 구입을 쉽게 하는 법안을 포함해 연방 규제를 철폐하는 14개의 의회 검토법 결의안에 서명했습니다.[239] 취임 첫 6주 동안 그는 종종 "규제 산업의 요청에 따라"[240] 90개의 연방 규정을 연기, 중단 또는 번복했습니다.[241] 정책청렴연구소는 트럼프의 제안 중 78%가 법원에 의해 막혔거나 소송에서 우위를 점하지 못한 것으로 파악했습니다.[242]

건강관리

선거 운동 기간 동안, 트럼프는 건강보험법(ACA)을 폐지하고 대체하겠다고 약속했습니다.[243] 재임 중 행정명령 13765호와[244] 13813호를 통해 법 시행을 축소했습니다.[245] 트럼프는 "오바마케어를 실패하게 내버려두고 싶다"는 바람을 나타냈습니다. 그의 행정부는 ACA 가입 기간을 절반으로 줄이고 가입 촉진을 위한 자금을 대폭 줄였습니다.[246][247] 트럼프는 ACA가 제공하는 기존 조건의 적용 범위를 저장했다고 거짓으로 주장했습니다.[248] 2018년 6월, 트럼프 행정부는 연방대법원에서 개인 위임과 관련된 재정적 처벌의 철폐가 ACA를 위헌으로 만들었다고 주장하면서 공화당이 주도하는 18개 주에 합류했습니다.[249][250] 그들이 성공했다면 최대 2,300만 명의 미국인에 대한 건강보험 적용이 사라졌을 것입니다.[249] 2016년 캠페인 기간 동안 트럼프는 메디케어 및 기타 사회 안전망 프로그램에 대한 자금을 보호하겠다고 약속했지만 2020년 1월에는 이러한 프로그램에 대한 삭감을 고려할 의향이 있다고 제안했습니다.[251]

트럼프는 오피오이드 유행에 대응하기 위해 2018년 약물 치료에 대한 자금을 늘리는 법안에 서명했지만 구체적인 전략을 세우지 못해 광범위한 비판을 받았습니다. 미국의 오피오이드 과다 복용 사망자는 2018년에 약간 감소했지만 2019년에는 사상 최대인 50,052명의 사망자로 급증했습니다.[252]

사회문제

트럼프는 낙태나 낙태 의뢰를 제공하는 기관들이 연방 기금을 받는 것을 금지했습니다.[253] 그는 "전통적인 결혼"을 지지한다고 말했지만, 동성 결혼의 전국적인 합법성은 "정착된" 문제라고 생각했습니다.[254] 2017년 3월, 그의 행정부는 성소수자 차별에 대한 오바마 행정부의 직장 보호의 주요 구성 요소를 철회했습니다.[255] 2020년 8월 트럼프가 시도한 트랜스젠더 환자에 대한 차별 방지 보호 롤백은 7월 대법원의 판결로 직원들의 민권 보호가 성 정체성과 성적 지향으로 확대된 후 연방 판사에 의해 중단되었습니다.[256]

트럼프는 시간이 지남에 따라 견해가 바뀌었지만 일반적으로 총기 규제에 반대한다고 말했습니다.[257] 임기 중 여러 차례 총기 난사 사건이 발생하자 총기 관련 법안을 발의하겠다고 밝혔지만 2019년 11월 그 노력을 포기했습니다.[258] 그의 행정부는 마리화나를 합법화한 주들에 대한 보호를 제공했던 오바마 시대의 정책들을 철회하면서 마리화나 반대 입장을 취했습니다.[259]

트럼프는 오랫동안 사형제를 옹호해 왔습니다.[260][261] 그의 정부 하에서 연방 정부는 이전 56년을 합친 것보다 더 많은 13명의 죄수를 처형했고 17년 동안의 유예 기간을 거친 후였습니다.[262] 2016년 트럼프는 워터보딩[263][264] 등 심문 고문 방식 사용을 지지한다고 밝혔으나 이후 제임스 매티스 국방장관의 반대로 이를 철회하는 모습을 보였습니다.[265]

사면 및 감형

트럼프는 조지 H. W. 부시와 조지 W. 부시를 제외한 1900년 이후 모든 대통령보다 적은 237건의 사면 요청을 했습니다.[266] 그들 중 25명만이 법무부의 사면 변호사 사무소에 의해 조사를 받았고, 나머지는 그와 그의 가족, 그리고 그의 동맹자들과 개인적 또는 정치적 관계가 있는 사람들에게 허락되거나 유명인들에 의해 추천되었습니다.[267][268]

2017년부터 2019년까지 그는 잠수함 내부의 기밀 지역 사진을 찍은 혐의로 유죄 판결을 받은 전 해군 선원 크리스티안 소시에와 우익 해설가 디네시 수자를 사면했습니다.[269][270] 유명 인사 킴 카다시안의 요청에 따라 트럼프는 마약 밀매 혐의로 유죄 판결을 받은 앨리스 마리 존슨의 종신형을 감형했습니다.[271] 트럼프는 아프가니스탄이나 이라크에서 전쟁 범죄를 저지른 혐의로 유죄 판결을 받았거나 기소된 미군 3명의 형을 사면하거나 번복하기도 했습니다.[272]

2020년 11월과 12월에, 트럼프 대통령은 2007년 니수르 광장 학살 사건에서 이라크 민간인을 살해한 혐의로 유죄 판결을 받은 블랙워터 민간 보안 계약자 4명,[273] 화이트칼라 범죄자 마이클 밀켄과 버나드 케릭,[274] 딸 이방카의 장인 찰스 쿠슈너,[268] 2016년 러시아 대선 개입 수사 결과 유죄 판결을 받은 5명을 사면했습니다. 선거 그들 중에는 마이클 플린, 로저 스톤, 그가 이미 7월에 저지른 거짓말, 증인 조작, 방해 혐의로 40개월 형을 선고받은 폴 매너포트가 있었습니다.[275]

트럼프는 취임 마지막 하루 동안 스티브 배넌과 트럼프 기금 모금자 엘리엇 브로디를 포함해 73건의 사면을 내리고 70건의 형을 감형했습니다.[276]

라파예트 광장 시위자 제거 및 사진 작업

2020년 6월 1일, 조지 플로이드 시위 동안, 연방 법 집행 관리들은 백악관 밖 라파예트 광장에서 평화로운 시위대 무리를 제거하기 위해 경찰봉, 고무탄, 후추 스프레이 발사체, 기절 수류탄 및 연기를 사용했습니다.[277][278] 그리고 나서 트럼프는 성으로 걸어갔습니다. 전날 밤 시위대가 작은 불을 지른 요한 성공회; 그는 성경을 들고 사진을 찍기 위해 포즈를 취했고, 이후 행정부 고위 관리들이 그와 함께 사진을 찍었습니다.[277][279] 트럼프는 6월 3일 시위자들이 "[5월 31일] 교회를 불태우려 했고 거의 성공했기 때문에 (시위자들이) 무혐의 처분을 받았다"며 교회를 "심각하게 다쳤다"고 설명했습니다.[280]

종교 지도자들은 시위자들에 대한 대우와 사진 촬영 기회 자체를 비난했습니다.[281] 많은 은퇴한 군 지도자들과 국방부 관리들은 반 경찰-잔학한 시위자들에 맞서 미군을 사용하자는 트럼프의 제안을 비난했습니다.[282]

이민

트럼프가 제안한 이민 정책은 선거운동 기간 동안 격렬하고 논쟁적인 논쟁거리였습니다. 그는 불법 이동을 제한하기 위해 멕시코와 미국 국경에 장벽을 세울 것을 약속하고 멕시코가 그 비용을 지불할 것이라고 맹세했습니다.[283] 그는 미국에 거주하는 수백만 명의 불법 이민자들을 추방하겠다고 약속했고,[284] 출생 시민권이 "앵커 베이비"를 장려한다고 비판했습니다.[285] 대통령으로서, 그는 자주 불법 이민을 "침략"으로 묘사했고, 불법 이민자들을 범죄 조직인 MS-13과 혼동했습니다.[286] 하지만, 이용 가능한 연구에 따르면 불법 이민자들은 토착 미국인들보다 범죄율이 낮습니다.[287][288]

트럼프는 중앙 아메리카 출신 망명 신청자들에 대해 그 어떤 현대 미국 대통령보다도 더 가혹한 이민 집행 정책을 시행하는 등 이민 집행을 대폭 강화하려고 시도했습니다.[289][290]

2018년부터 트럼프는 거의 6,000명의 병력을 미국에 배치했습니다.– 멕시코 국경[291], 대부분의 중미 이주민들이 미국 망명 신청하는 것을 막습니다. 2020년, 그의 행정부는 정부 혜택을 사용할 수 있는 이민자들이 영주권을 얻는 것을 더 제한하기 위해 공공 요금 규정을 넓혔습니다.[292] 트럼프는 미국에 들어오는 난민 수를 사상 최저치로 줄였습니다. 트럼프가 취임했을 때 연간 한도는 11만 명이었고, 트럼프는 2020 회계연도에 18,000명, 2021 회계연도에 15,000명으로 한도를 설정했습니다.[293][294] 트럼프 행정부가 시행한 추가적인 제한 조치로 난민 신청 처리에 상당한 병목 현상이 발생하여 허용 한도에 비해 수용된 난민 수가 적었습니다.[295]

여행금지

2015년 샌버나디노 공격 이후 트럼프는 더 강력한 검사 시스템이 시행될 때까지 무슬림 외국인의 미국 입국을 금지할 것을 제안했습니다.[296] 그는 이후 "테러 역사가 입증된" 국가에 적용하기 위해 제안된 금지를 재구성했습니다.[297]

2017년 1월 27일, 트럼프는 안보 문제를 이유로 120일 동안 난민의 입국을 중단하고 이라크, 이란, 리비아, 소말리아, 수단, 시리아, 예멘 시민의 입국을 90일 동안 거부하는 행정명령 13769에 서명했습니다. 명령은 즉시 그리고 예고 없이 발효되어 공항에 혼란과 혼란을 야기했습니다.[298][299] 이 금지에 반대하는 시위는 다음날 공항에서 시작되었습니다.[298][299] 이 명령에 대한 법적 문제는 전국적인 예비 금지를 초래했습니다.[300] 이라크를 제외하고 다른 면제를 주었던 3월 6일의 수정 명령이 다시 3개 주의 연방 판사들에 의해 막혔습니다.[301][302] 2017년 6월 결정에서 대법원은 "미국에 있는 개인 또는 기업과의 신뢰할 수 있는 관계에 대한 신뢰할 수 있는 주장"이 부족한 방문객에게 금지를 시행할 수 있다고 판결했습니다.[303]

이 임시 명령은 2017년 9월 24일 대통령령 9645로 대체되었으며, 이는 이라크와 수단을 제외한 원래 대상국으로부터의 여행을 제한하고, 또한 특정 베네수엘라 관리들과 함께 북한과 차드로부터의 여행을 금지했습니다.[304] 하급 법원이 새로운 제한을 부분적으로 차단한 후 대법원은 2017년 12월 4일 9월 버전이 완전히 발효되도록 [305]허용했으며 2019년 6월 판결에서 최종적으로 여행 금지를 유지했습니다.[306]

국경에서의 가족 분리

트럼프 행정부는 이주 가정의 자녀 5,400여 명을 미국 부모와 분리했습니다.–멕시코 국경,[307][308] 2017년 여름부터 국경에서 이산가족 수 급증 2018년 4월, 트럼프 행정부는 불법 입국으로 의심되는 모든 성인을 형사 기소하는 "무관용" 정책을 발표했습니다.[309] 이로 인해 이주한 성인들은 기소를 위해 형사 구금된 반면, 자녀는 동반되지 않은 외국인 미성년자로 분리되어 가족 분리가 이루어졌습니다.[310] 행정부 관리들은 이 정책이 불법 이민을 저지하는 방법이라고 설명했습니다.[311]

이산가족 정책은 역대 정권에서 전례가 없던 것으로 국민적 공분을 불러일으켰습니다.[311][312] 트럼프는 분리가 행정부의 정책임에도 불구하고 민주당을 비난하며 자신의 행정부가 법을 따른 것일 뿐이라고 거짓 주장했습니다.[313][314][315]

트럼프는 당초 행정명령으로 별거를 중단할 수 없다고 주장했지만, 2018년 6월 20일 강력한 대중의 반대에 동의하고 이주 가족을 함께 구금하는 것이 아이에게 위험을 초래하지 않는 한 함께 구금할 것을 의무화하는 행정명령에 서명했습니다.[316][317] 2018년 6월 26일, 다나 사브로 판사는 트럼프 행정부가 분리된 아이들을 추적할 수 있는 시스템이 없으며 가족 소통과 통일을 위한 효과적인 조치가 없다고 결론을 내렸습니다.[318] 사브로 판사는 제한된 상황을 제외하고는 가족들을 다시 만나고 가족 분리를 중단하라고 명령했습니다.[319] 연방 법원의 명령 이후, 트럼프 행정부는 천 명이 넘는 이주 아동들을 가족과 분리했습니다. ACLU는 트럼프 행정부가 재량권을 남용했다고 주장하며 사브로우에게 분리가 필요한 상황을 좀 더 좁게 규정해달라고 요청했습니다.[308]

트럼프 장벽과 정부 폐쇄

트럼프의 중앙 선거 공약 중 하나는 멕시코에 1000마일(1600km)의 국경 장벽을 건설하고 멕시코가 비용을 지불하도록 하는 것이었습니다.[320] 그의 임기가 끝날 때까지, 미국은 장벽이 없었던 장소에 "40마일[64km]의 새로운 1차 장벽과 33마일[53km]의 2차 장벽"을 세웠고, 365마일(587km)의 1차 또는 2차 국경 울타리가 낡거나 낡은 장벽을 대체했습니다.[321]

2018년 트럼프는 국경장벽을 위한 56억 달러의 자금을 배정하지 않으면 의회의 세출법안에 서명하기를 거부했고,[322] 이로 인해 연방정부는 2018년 12월부터 2019년 1월까지 35일 동안 부분적으로 폐쇄되었는데, 이는 역사상 가장 긴 미국 정부 폐쇄였습니다.[323][324] 약 80만 명의 공무원들이 휴직하거나 무급으로 일했습니다.[325] 트럼프와 의회는 공무원들에게 지연된 지불금을 제공했지만 장벽을 위한 자금은 제공하지 않은 임시 자금을 승인함으로써 셧다운을 종료했습니다.[323] 의회 예산국에 따르면, 셧다운으로 인해 경제에 30억 달러의 영구적인 손실이 발생했습니다.[326] 조사 대상자의 절반가량이 셧다운의 책임을 트럼프에게 돌렸고, 트럼프의 지지율은 하락했습니다.[327]

2019년 2월에 임박한 또 다른 셧다운을 막기 위해 의회가 통과되었고 트럼프는 55마일(89km)의 볼라드 국경 펜싱에 13억 7500만 달러가 포함된 자금 법안에 서명했습니다.[328] 트럼프는 또 의회가 배정한 61억 달러의 자금을 다른 용도로 전용하려는 의도로 남부 국경에 국가비상사태를 선포했습니다.[328] 트럼프는 선언문을 뒤집기 위한 공동 결의안에 거부권을 행사했고, 상원은 거부권 행사에 반대표를 던졌습니다.[329] 국방부의 마약 단속 활동을[330][331] 위한 25억 달러와 군사 건설을[332][333] 위한 36억 달러의 전용에 대한 법적 도전은 실패했습니다.

외교정책

트럼프는 자신을 "민족주의자"[334]로, 자신의 외교 정책을 "미국 우선주의자"로 표현했습니다.[335] 그의 외교 정책은 포퓰리즘, 신민족주의, 권위주의 정부에 대한 찬사와 지지로 특징지어졌습니다.[336] 트럼프 재임 기간 동안 대외 관계의 특징은 예측 불가능과 불확실성,[335] 일관된 정책의 부재,[337] 유럽 동맹국과의 긴장되고 때로는 적대적인 관계를 포함했습니다.[338] 그는 NATO 동맹국들을 비난하고 미국이 NATO에서 탈퇴해야 한다고 여러 차례 비공개로 제안했습니다.[339][340]

거래

트럼프는 환태평양경제동반자협정(TPP) 협상에서 미국을 [341]탈퇴하고 철강과 알루미늄 수입품에 관세를 부과했으며,[342] 미국으로 수입되는 중국산 물품 818개 품목(500억 달러 상당)에 대한 관세를 대폭 인상하는 등 중국과 무역전쟁에 나섰습니다.[343] 트럼프는 수입 관세는 중국이 미 재무부에 납부한다고 밝힌 반면, 그것들은 중국에서 상품을 수입하는 미국 회사들에 의해 지불됩니다.[344] 그는 캠페인 기간 동안 미국의 대규모 무역 적자를 크게 줄이겠다고 약속했지만, COVID-19 팬데믹 기간인 2020년 7월 무역 적자는 "2008년 7월 이후 월간 최대 적자"였습니다.[345] 미국-멕시코-캐나다 협정(USMCA)은 2017~2018년 재협상을 거쳐 2020년 7월 NAFTA의 후속 협정으로 발효되었습니다.[346]

러시아

로이터통신에 따르면 트럼프 행정부는 2014년 크림반도를 합병한 뒤 "미국이 러시아 기업에 부과한 가장 강력한 처벌을 물타기 했다"고 밝혔습니다.[347][348] 트럼프는 러시아의 불이행을 이유로 미국을 중거리핵전력조약에서 탈퇴시키고,[349] 러시아의 G7 복귀 가능성을 지지했습니다.[350]

트럼프는 블라디미르 푸틴[351][352] 러시아 대통령을 칭찬하고 거의 비판하지 않았지만 러시아 정부의 일부 행동에 반대했습니다.[353][354] 트럼프는 2018년 헬싱키 정상회의에서 푸틴 대통령을 만난 뒤 미국 정보기관의 조사 결과를 수용하기보다 2016년 대선에서 푸틴 대통령이 러시아의 개입을 부인한 것을 수용해 초당적인 비판을 받았습니다.[355][356][357] 트럼프는 푸틴 대통령과 함께 아프가니스탄에서 미군을 공격한 탈레반 전사들에게 제공된 러시아의 현상금 의혹에 대해서는 언급하지 않았으며, 정보를 의심하고 보고받지 못했다고 말했습니다.[358]

중국

트럼프 대통령은 대통령직을 전후해 중국이 미국을 부당하게 이용하고 있다고 거듭 비난했습니다.[359] 트럼프 대통령은 실패로 널리 특징지어지는 중국을 상대로 무역전쟁을 일으켰고,[360][361][362] 이란과의 유대관계 의혹에 대해 화웨이를 제재했으며,[363] 중국 학생과 학자들에 대한 비자 제한을 크게 늘렸습니다.[364] 그리고 중국을 환율조작국으로 분류했습니다.[365] 트럼프는 중국에 대한 막말 공격과 시진핑 중국 공산당 지도자에 대한 칭찬을 병치하기도 했는데,[366] 무역전쟁 협상의 결과로 분석됐습니다.[367] 당초 중국의 코로나19 대처를 높이 평가한 [368]뒤 2020년 3월부터 비판 캠페인을 시작했습니다.[369]

트럼프 대통령은 무역협상을 위태롭게 할 것을 우려해 중국이 신장 지역 소수민족을 상대로 인권을 유린한 것에 대해 처벌하는 것에 반대한다고 밝혔습니다.[370] 2020년 7월, 트럼프 행정부는 중국의 위구르 소수민족 중 100만 명 이상을 수용하는 대규모 수용소를 확대한 것에 대응하여 중국 고위 관리들에 대한 제재와 비자 제한을 가했습니다.[371]

북한

북한의 핵무기가 점점 더 심각한 위협으로 인식되던 2017년,[372] 트럼프는 북한의 공격이 "세계가 본 적이 없는 불과 분노"에 직면하게 될 것이라고 경고하며 수사력을 높였습니다.[373][374] 2017년, 트럼프는 북한의 "완전한 비핵화"를 원한다고 선언했고, 김정은 지도자와 이름을 날리는 일을 했습니다.[373][375]

이 긴장의 시기가 지나고 트럼프와 김 위원장은 최소한 27통의 편지를 주고 받았는데, 두 사람은 따뜻한 개인적 우정을 묘사했습니다.[376][377] 트럼프는 2018년 싱가포르, 2019년 하노이, 2019년 한국 비무장지대에서 김 위원장을 세 번 만났습니다.[378] 트럼프는 북한 지도자를 만나거나 북한 땅에 발을 디딘 첫 현직 미국 대통령이 됐습니다.[378] 트럼프는 미국의 대북 제재도 일부 해제했습니다.[379]

하지만 비핵화 합의는 이뤄지지 않았고,[380] 2019년 10월 회담은 하루 만에 결렬됐습니다.[381] 2017년 이후 핵실험을 하지 않는 동안 북한은 핵무기와 탄도미사일의 무기고를 계속해서 쌓아왔습니다.[382][383]

아프가니스탄

아프가니스탄 주둔 미군은 2017년 1월 8,500명에서 1년 후 1만 4,000명으로 [384]늘어 아프가니스탄 추가 개입에 비판적인 트럼프의 선거 전 입장을 뒤집었습니다.[385] 2020년 2월, 트럼프 행정부는 "미국이나 동맹국을 공격할 목적으로 테러리스트들에 의해 아프간 땅이 사용되지 않을 것이라는 탈레반의 보장에 대한 합의"와 미국이 5명의 석방을 요구하는 조건부 평화 협정을 탈레반과 체결했습니다.아프가니스탄 정부에 의해 투옥된 탈레반 000명.[386][387][388] 트럼프의 임기가 끝날 때까지 5,000명의 탈레반이 석방되었고, 탈레반이 아프간군에 대한 공격을 계속하고 알카에다 조직원들을 지도부에 통합했음에도 불구하고, 미군은 2,500명으로 줄었습니다.[388]

이스라엘

트럼프는 베냐민 네타냐후 이스라엘 총리의 많은 정책을 지지했습니다.[389] 트럼프 대통령 시절 미국은 예루살렘을 이스라엘의[390] 수도로 인정하고 골란고원에 대한 이스라엘의 주권을 인정하면서 [391]유엔총회, 유럽연합, 아랍연맹 등 국제사회의 비난을 받았습니다.[392][393] 2020년, 백악관은 아랍 에미리트 연합국 및 바레인과 이스라엘의 대외 관계를 정상화하면서 아브라함 협정의 서명을 주최했습니다.[394]

사우디아라비아

트럼프는 후티에 대항하는 사우디아라비아 주도의 예멘 개입을 적극 지지했고, 2017년 사우디아라비아에 무기를 판매하는 1,100억 달러 규모의 협정을 체결했습니다.[395] 2018년 미국은 개입을 위해 제한된 정보와 병참 지원을 제공했습니다.[396][397] 2019년 미국과 사우디아라비아가 이란 탓으로 돌린 사우디 석유시설 공격에 이어 트럼프 대통령은 전투기 편대와 패트리엇 포대 2개, 고고도미사일방어체계(THAAD·사드) 등 미군 3천 명을 사우디와 아랍에미리트에 추가 배치하는 것을 승인했습니다.[398]

시리아

트럼프는 2017년 4월과 2018년 4월 시리아 아사드 정권에 대해 각각 칸 샤이쿤과 두마 화학 공격에 대한 보복으로 미사일 타격을 명령했습니다.[399][400] 2018년 12월, 트럼프는 국방부의 평가와 배치되는 "우리는 IS에 승리했다"고 선언하고 시리아에서 모든 군대를 철수하라고 명령했습니다.[401][402] 다음날 매티스 장관은 자신의 결정이 IS와 싸우는 데 핵심적인 역할을 한 미국 쿠르드 동맹국들의 포기라며 항의하며 사임했습니다.[403] 2019년 10월, 트럼프 대통령이 레제프 타이이프 에르도 ğ 터키 대통령과 통화한 후 시리아 북부의 미군이 이 지역에서 철수하고 튀르키예가 시리아 북부를 침공하여 미국 동맹 쿠르드족을 공격하고 대체했습니다. 그 달 말, 미국 하원은 354 대 60의 보기 드문 초당적 투표에서 트럼프의 시리아 주둔 미군 철수를 "미국 동맹국을 버리고, IS와의 투쟁을 약화시키고, 인도주의적 재앙을 촉발시켰다"고 비난했습니다.[405][406]

이란

2018년 5월, 트럼프는 이란이 핵 프로그램 제한에 동의하는 대가로 이란에 대한 대부분의 경제 제재를 해제한 2015년 합의인 포괄적 공동 행동 계획에서 미국을 탈퇴했습니다.[407][408] 분석가들은 미국의 철수 이후 이란이 핵무기 개발에 더욱 근접했다고 판단했습니다.[409]

2020년 1월 1일, 트럼프는 지난 20년 동안 이란군의 거의 모든 중요한 작전을 계획했던 카셈 솔레이마니 이란 장군을 사살한 미군 공습을 명령했습니다.[410][411] 트럼프는 이란이 보복할 경우 이란 사이트 52곳을 타격하겠다고 위협했습니다.[412] 1월 8일, 이란은 이라크에 있는 두 개의 미국 공군기지에 대해 탄도 미사일 공격으로 보복했습니다. 수십 명의 군인들이 외상성 뇌손상을 입었습니다. 그들의 부상은 트럼프에 의해 경시되었고, 그들은 처음에 Purple Hearts와 그것의 수령자에 따른 특별 혜택을 거부당했습니다.[413][409] 같은 날 미국과 이란의 긴장이 고조되는 가운데 이란은 테헤란 공항에서 이륙한 우크라이나 국제항공 752편 여객기를 실수로 격추했습니다.[414][relevant?]

2020년 8월, 트럼프 행정부는 이란에 대한 유엔 제재의 복귀로 이어질 수 있는 합의의 일부인 메커니즘을 촉발하려고 시도했지만 실패했습니다.[415]

인사

트럼프 행정부는 특히 백악관 직원들의 인사 회전율이 높았습니다. 트럼프의 취임 첫 해 말까지, 그의 원래 직원의 34%가 사임하거나 해고되거나 다시 임명되었습니다.[416] 2018년[update] 7월 초 기준으로 트럼프의 고위 보좌관 중 61%가 떠났고[417] 141명의 직원이 전년도에 떠났습니다.[418] 두 수치 모두 최근 대통령 기록을 세웠습니다. 즉, 그의 전임자 4명이 처음 2년 동안 본 것보다 첫 13개월 동안 더 많은 변화가 있었습니다.[419] 주목할 만한 조기 출발에는 플린 백악관 국가안보보좌관(재임 25일 만)과 숀 스파이서 공보비서관이 포함됐습니다.[419] 배넌, 호프 힉스, 존 맥엔티, 키스 실러 등 트럼프 대통령의 측근들이 그만두거나 쫓겨났습니다.[420] 힉스와 맥엔티를 포함한 일부는 이후 다른 직책을 맡아 백악관으로 돌아갔습니다.[421] 트럼프는 자신의 전직 고위 관료들을 공개적으로 폄하하면서, 그들을 무능하고, 멍청하거나, 미친 사람들이라고 불렀습니다.[422]

트럼프는 백악관 비서실장 4명을 두고 여러 명을 소외시키거나 밀어냈습니다.[423] 라인스 프리버스는 은퇴한 해병대 장군 존 F에 의해 7개월 만에 대체되었습니다. 켈리.[424] 켈리는 2018년 12월 그의 영향력이 약화된 격동의 재임 기간 후 사임했고, 트럼프는 그를 폄하했습니다.[425] 켈리의 뒤를 이어 믹 멀베이니가 비서실장 대행을 맡았고, 2020년 3월 마크 메도스가 후임으로 임명되었습니다.[423]

2017년 5월 9일, 트럼프는 FBI 국장 제임스 코미를 해임했습니다. 트럼프는 처음에는 이런 행동을 힐러리 클린턴의 이메일에 대한 조사에서 코미의 행동 때문으로 돌리면서도 며칠 뒤 진행 중인 트럼프-러시아 조사에서 코미의 역할이 우려된다며 코미를 더 일찍 해고할 의도라고 말했습니다.[426] 트럼프는 지난 2월 비공개 대화에서 코미 국장이 플린에 대한 수사를 취하하기를 바란다고 말했습니다.[427] 트럼프는 지난 3월과 4월 코미 전 국장에게 FBI가 자신을 조사하지 않고 있다고 공개적으로 말하면서 "행동 능력을 손상시키는 클라우드를 해제해달라"고 요청했습니다.[427][428]

트럼프 내각 내에서는 상대적으로 이직률이 높았습니다.[420] 트럼프는 첫 해에 15명의 원래 내각 구성원 중 3명을 잃었습니다.[429] 톰 프라이스 보건복지부 장관은 지난 2017년 9월 민간 전세기와 군용기의 과도한 사용으로 인해 사임할 수밖에 없었습니다.[429][420] 스콧 프루이트 환경보호청 행정관은 2018년에 사임했고 라이언 징크 내무장관은 2019년 1월에 여러 차례 조사를 받으면서 사임했습니다.[430][431]

트럼프는 행정부 내 2군 간부들을 임명하는 데는 상당 부분 불필요한 자리라며 지지부진했습니다. 2017년 10월에도 지명자 없이 수백 명의 부내각 자리가 남아 있었습니다.[432] 2019년 1월 8일까지 706개 주요 직책 중 433명(61%)이 채워졌고 트럼프는 264명(37%)의 지명자가 없었습니다.[433]

사법부

트럼프는 항소법원에 54명, 대법원에 닐 고서치, 브렛 캐버노, 에이미 코니 배럿 등 3명을 포함해 226명의 3조 판사를 임명했습니다.[434] 그의 대법원 지명자들은 정치적으로 법원을 우경화시킨 것으로 주목받았습니다.[435][436][437][438] 2016년 선거운동에서 그는 로 대 웨이드가 당선되면 "자동적으로" 뒤집힐 것이며 2~3명의 친생명 대법관을 임명할 수 있는 기회를 제공할 것이라고 약속했습니다. 그는 나중에 밥스 대 잭슨 여성 건강 기구에서 로가 역전되었을 때 공로를 인정받았습니다. 그의 대법원 지명자 3명 모두가 과반수로 투표했습니다.[439][440][441]

트럼프는 종종 개인적인 측면에서 동의하지 않는 법원과 판사들을 폄하하고 사법부의 헌법적 권한에 의문을 제기했습니다. 법원에 대한 그의 공격은 현직 연방 판사들을 포함한 관찰자들로부터 그의 진술이 사법 독립과 사법부에 대한 대중의 신뢰에 미치는 영향에 대해 비난을 받았습니다.[442][443][444]

코로나19 범유행

초동응답

2019년 12월 중국 우한에서 코로나19가 발생해 수주 만에 전 세계로 확산됐습니다.[445][446] 2020년 1월 20일 미국에서 첫 확진자가 보고되었습니다.[447] 이번 발병은 2020년 1월 31일 보건복지부(HHS) 장관 알렉스 아자르(Alex Azar)에 의해 공식적으로 공중보건 비상사태로 선언되었습니다.[448] 트럼프는 처음에는 지속적인 공중 보건 경고와 행정부 내 보건 당국자와 아자르 장관의 조치를 요구하는 것을 무시했습니다.[449][450] 1월과 2월 내내 그는 발병에 대한 경제적, 정치적 고려에 집중했습니다.[451] 2020년 2월 트럼프는 미국에서의 발병이 인플루엔자보다 덜 치명적이고 "매우 통제되고 있다"며 곧 끝날 것이라고 공개적으로 주장했습니다.[452] 2020년 3월 19일, 트럼프는 밥 우드워드에게 "패닉을 일으키고 싶지 않기 때문에 의도적으로 그것을 경시하고 있다"고 사적으로 말했습니다.[453][454]

3월 중순까지 대부분의 글로벌 금융 시장은 신흥 팬데믹에 대응하여 심각하게 위축되었습니다.[455] 3월 6일, 트럼프는 연방 기관에 83억 달러의 긴급 자금을 지원하는 코로나바이러스 준비 및 대응 보완 세출법에 서명했습니다.[456] 3월 11일, 세계보건기구(WHO)는 COVID-19를 팬데믹으로 인정했고,[445] 트럼프는 3월 13일부터 유럽 대부분 지역에 대한 부분적인 여행 제한을 발표했습니다.[457] 같은 날 그는 전국적인 백악관 연설에서 바이러스에 대한 첫 번째 심각한 평가를 내렸으며, 이번 발병은 "끔찍하지만 일시적인 순간"이라며 금융 위기는 없었다고 말했습니다.[458] 3월 13일, 그는 국가 비상사태를 선포하여 연방 자원을 해방시켰습니다.[459] 트럼프는 시험 가능성이 심각하게 제한되어 있음에도 불구하고 "시험을 원하는 사람은 누구나 시험을 받을 수 있다"고 거짓 주장했습니다.[460]

4월 22일, 트럼프는 일부 형태의 이민을 제한하는 행정 명령에 서명했습니다.[461] 감염자와 사망자가 계속 증가하는 늦봄과 초여름, 그는 팬데믹에 대한 초기 평가가 지나치게 낙관적이거나 대통령 리더십을 제공하지 못한 것을 받아들이기보다는 주들을 탓하는 전략을 채택했습니다.[462]

트럼프는 2020년 1월 29일 백악관 코로나바이러스 태스크포스를 설립했습니다.[463] 3월 중순부터 트럼프는 매일 의료 전문가와 다른 행정부 관리들이 참석한 태스크포스 기자 회견을 열었고,[464] 때때로 입증되지 않은 치료법을 홍보함으로써 그들에게 동의하지 않았습니다.[465] 트럼프는 브리핑에서 주요 연사로 나서 팬데믹에 대한 자신의 대응을 칭찬하고, 경쟁자인 조 바이든 대선 후보를 자주 비판하며 언론을 비난했습니다.[464][466] 3월 16일, 그는 처음으로 팬데믹이 통제되고 있지 않으며 일상 생활에 수개월 동안의 혼란과 경기 침체가 발생할 수 있음을 인정했습니다.[467] 그가 코로나19를 설명하기 위해 '중국 바이러스'와 '중국 바이러스'를 반복적으로 사용한 것은 보건 전문가들의 비판을 받았습니다.[468][469][470]

4월 초, 팬데믹이 악화되고 행정부의 대응에 대한 비판 속에서 트럼프는 발병 대처에 대한 실수를 인정하지 않고 언론, 민주당 주지사, 이전 행정부, 중국 및 WHO를 비난했습니다.[471] 코로나바이러스 태스크포스 일일 브리핑은 트럼프 대통령이 코로나19 치료를 위해 소독제를 주입하는 위험한 아이디어를 제안한 브리핑 이후인 4월 말에 끝났습니다.[472] 이 발언은 의료 전문가들에게 광범위한 비난을 받았습니다.[473][474]

5월 초 트럼프는 코로나바이러스 태스크포스의 단계적 탈퇴와 경제 재개를 중심으로 한 다른 그룹으로의 교체를 제안했습니다. 반발이 일고 있는 가운데 트럼프 대통령은 태스크포스가 "무한히" 계속될 것이라고 말했습니다.[475] 5월 말까지 코로나바이러스 태스크포스 회의를 대폭 축소했습니다.[476]

세계보건기구

팬데믹 이전에 트럼프는 WHO와 다른 국제 기구들을 비난했는데, 그는 이 기구들이 미국의 원조를 이용하고 있다고 주장했습니다.[477] 지난 2월 공개된 그의 행정부가 제안한 2021년 연방 예산은 WHO의 자금 지원을 절반 이상 줄일 것을 제안했습니다.[477] 지난 5월과 4월 트럼프 대통령은 WHO가 코로나19를 "심각하게 잘못 관리하고 있다"고 비난했고, 이 조직이 중국의 통제 하에 있으며 중국 정부가 팬데믹의 기원을 은폐할 수 있도록 했다고 증거 없이 주장했으며,[477][478][479] 이 조직에 대한 자금 지원을 철회한다고 발표했습니다.[477] 이것들은 그가 팬데믹을 잘못 처리하는 것을 방해하기 위한 시도로 여겨졌습니다.[477][480][481] 2020년 7월, 트럼프는 2021년 7월부터 미국의 WHO 공식 탈퇴를 발표했습니다.[478][479] 이 결정은 보건 및 정부 관계자들에 의해 "근시안적", "센스 없는", "위험한" 결정으로 널리 비난 받았습니다.[478][479]

팬데믹 완화 조치 포기 압력

2020년 4월, 공화당 관련 단체들은 주 정부가 팬데믹과 싸우기 위해 취하고 있는 조치에 반대하는 봉쇄 반대 시위를 조직했습니다.[482][483][484] 트럼프는 대상 주들이 트럼프 행정부의 재개 지침을 충족하지 않았음에도 불구하고 트위터에서 시위를 장려했습니다.[485] 2020년 4월, 그는 처음에 브라이언 켐프 조지아 주지사의 일부 필수적이지 않은 사업을 재개하려는 계획을 지지했다가 나중에 비판했습니다.[486] 봄 내내 그는 점점 더 국가 경제에 대한 피해를 되돌리기 위해 규제를 중단할 것을 촉구했습니다.[487] 트럼프는 공공장소에서[488] 마스크를 착용하라는 행정부의 2020년 4월 지침과 달리 공개 행사에서 마스크 착용을 거부하는 경우가 많았고, 마스크가 바이러스 확산 방지에 중요하다는 의학적 합의가 거의 일치했음에도 불구하고 마스크 착용을 거부했습니다.[489] 6월까지 트럼프는 마스크가 "양날의 검"이라고 말했고, 마스크 착용에 대해 바이든을 조롱했으며, 마스크 착용은 선택 사항이라고 지속적으로 강조했으며, 마스크 착용은 개인적으로 그에 대한 정치적 발언이라고 제안했습니다.[489] 트럼프의 의료권고 모순은 팬데믹 완화를 위한 국가적 노력을 약화시켰습니다.[488][489]

지난 6월과 7월 트럼프 대통령은 미국이 검사를 덜 하면 코로나바이러스 감염 사례가 줄어들 것이라며 보고된 사례가 많으면 "우리가 나빠 보인다"고 여러 차례 말했습니다.[490][491] 무증상자는 여전히 바이러스를 전파할 수 있기 때문에, 당시 CDC 지침은 바이러스에 노출된 사람은 증상을 보이지 않더라도 '신속하게 확인하고 검사'해야 한다는 것이었습니다.[492][493] 2020년 8월 CDC는 바이러스에 노출되었지만 증상을 보이지 않는 사람들에게 "검사가 반드시 필요한 것은 아니다"라고 조언하면서 조용히 검사 권고를 낮췄습니다. 지침 변경은 CDC 과학자들의 뜻을 거스르고 트럼프 행정부의 압력 아래 HHS 정치 지명자들에 의해 이루어졌습니다.[494][495] 이런 정치적 간섭이 보도된 다음 날, 검사 지침이 다시 원래 권고로 바뀌었습니다.[495]

6월 중순부터 미국에서 기록적인 코로나19 확진자 수와 양성 반응 비율이 증가하고 있음에도 불구하고 트럼프는 2020년 7월 초 코로나19 확진자의 99%가 "완전히 무해하다"고 허위 주장하는 등 팬데믹을 계속 경시했습니다.[496][497] 그는 7월에 보고된 사례가 급증했음에도 불구하고 모든 주가 가을에 대면 교육을 재개해야 한다고 주장하기 시작했습니다.[498]

보건 기관에 대한 정치적 압력

트럼프는 입증되지 않은 치료제를[499][500] 승인하거나 백신 승인 속도를 높이는 [494]등 자신이 선호하는 조치를 취하도록 연방 보건 기관에 거듭 압박했습니다.[500] HHS에 임명된 트럼프 행정부 정치인들은 팬데믹이 통제되고 있다는 트럼프의 주장을 훼손하는 대중에 대한 CDC 통신을 통제하려고 했습니다. CDC는 많은 변경 사항에 저항했지만 점점 더 HHS 직원이 기사를 검토하고 게시 전에 변경 사항을 제안할 수 있도록 허용했습니다.[501][502] 트럼프는 FDA 과학자들이 자신을 반대하는 "깊은 국가"의 일부이며 자신에게 정치적 타격을 주기 위해 백신과 치료제의 승인을 지연시키고 있다고 증거 없이 주장했습니다.[503]

백악관에서의 발병

2020년 10월 2일 트럼프는 트위터를 통해 백악관 발병의 일부인 [504][505]코로나19 양성 반응을 보였다고 밝혔습니다.[506][507] 트럼프 대통령은 이날 오후 발열과 호흡곤란으로 월터 리드 국립군사의료원에 입원한 것으로 알려졌습니다. 그는 항바이러스제와 실험용 항체 약물과 스테로이드로 치료를 받았습니다. 그는 10월 5일 백악관으로 돌아왔는데, 여전히 전염성이 있고 몸이 좋지 않았습니다.[506][508] 치료 중과 치료 후에도 그는 계속해서 바이러스를 경시했습니다.[506] 2021년, 그의 상태가 훨씬 심각했던 것으로 밝혀졌는데, 그는 위험할 정도로 낮은 혈중 산소 농도와 고열, 그리고 폐 침윤이 있어 심각한 경우를 나타냈습니다.[507]

2020년 대선 캠페인에 미치는 영향

2020년 7월까지 트럼프의 코로나19 팬데믹 대처는 대선의 주요 이슈가 되었습니다.[509] 바이든은 팬데믹을 중심 이슈로 삼고자 했습니다.[510] 여론조사에 따르면 유권자들은 트럼프의 팬데믹 대응을[509] 비난하고 바이러스와 관련된 그의 수사를 믿지 않았으며, Ipsos/ABC News 여론조사에 따르면 응답자의 65%가 트럼프의 팬데믹 대응에 찬성하지 않는 것으로 나타났습니다.[511] 캠페인의 마지막 몇 달 동안 트럼프는 사례와 사망자가 증가하고 있음에도 불구하고 미국이 팬데믹을 관리하는 데 "순회전"하고 있다고 반복적으로 주장했습니다.[512] 11월 3일 선거를 며칠 앞두고 미국에서는 처음으로 하루 만에 10만 건이 넘는 사례가 보고됐습니다.[513]

조사

취임 후, 트럼프는 그의 선거 운동, 정권 이양 및 취임, 대통령 재임 기간 동안 취해진 조치, 개인 사업, 개인 세금 및 자선 재단을 포함하여 법무부와 의회의 조사를 증가시키는 대상이었습니다.[514] 트럼프에 대한 수사는 연방 범죄 수사 10건, 주·지방 수사 8건, 의회 수사 12건 등 모두 30건이었습니다.[515]

2019년 4월, 하원 감독 위원회는 트럼프의 은행인 도이치 뱅크와 캐피털 원, 그리고 그의 회계 회사인 마자르 USA로부터 재무 정보를 요구하는 소환장을 발부했습니다. 그리고 나서 트럼프는 공개를 막기 위해 은행인 마자르와 위원장인 엘리야 커밍스를 고소했습니다.[516] 지난 5월 DC 지방법원의 아미트 메타 판사는 마자르가 소환장에 응해야 한다고 판결했고,[517] 뉴욕 남부 지방법원의 에드가르도 라모스 판사는 은행들도 응해야 한다고 판결했습니다.[518][519] 트럼프의 변호사들은 판결에 대해 항소했습니다.[520] 2022년 9월 위원회와 트럼프는 마자르에 대한 합의에 동의했고 회계법인은 문서를 넘겨주기 시작했습니다.[521]

쉬쉬머니 결제

2016년 대선 캠페인 기간 동안 내셔널 인콰이어러의 모회사인 아메리칸 미디어(AMI)와 [522]코언이 설립한 회사는 2006년에서 2007년 사이에 플레이보이 모델인 캐런 맥두걸과 성인 영화 배우 스토미 대니얼스가 트럼프와의 염문 의혹에 대해 침묵을 지킨 것에 대해 돈을 지불했습니다.[523] 코언은 2018년 대선에 영향을 미치기 위해 트럼프의 지시로 두 가지 지불을 모두 주선했다며 선거자금법을 위반했다고 유죄를 인정했습니다.[524] 트럼프는 사건을 부인하며 코언이 다니엘스에게 돈을 지불한 사실을 몰랐다고 주장했지만, 2017년에 그에게 배상했습니다.[525][526] 연방 검찰은 트럼프가 2014년부터 비공개 지급과 관련한 논의에 관여했다고 주장했습니다.[527] 법원 문서에 따르면 FBI는 2016년 10월 코언과 통화한 내용을 토대로 트럼프가 대니얼스에게 지불하는 데 직접적으로 관여했다고 믿었습니다.[528][529] 연방 검찰은 2019년에 수사를 [530]종결했지만 맨해튼 지방 검사는 트럼프[531] 조직과 AMI에 지불과 관련된 기록을, 트럼프와 트럼프 조직에 8년간의 세금 신고를 소환했습니다.[532] 2022년 11월, 뉴욕 타임즈는 맨해튼 검찰이 트럼프에 대해 "사건을 만드는 것에 대해 새롭게 낙관적"이라고 보도했습니다.[533]

러시아 선거 개입

2017년 1월, 국가정보국장으로 대표되는 CIA, FBI, NSA 등 미국 정보기관들은 공동으로 러시아 정부가 2016년 대선에 개입해 트럼프 당선을 유리하게 했다고 "높은 신뢰감"을 가지고 발언했습니다.[534][535] 2017년 3월 제임스 코미 FBI 국장은 의회에서 "[T]FBI는 방첩 임무의 일환으로 2016년 대선에 개입하려는 러시아 정부의 노력을 조사하고 있습니다. 여기에는 트럼프 캠페인과 관련된 개인과 러시아 정부 간의 연결의 본질과 캠페인과 러시아의 노력 사이에 조정이 있었는지 여부를 조사하는 것이 포함됩니다."[536] 트럼프 관계자들과 러시아 관리들과 스파이들 사이의 많은 의심스러운[537] 연관성이 발견되었고 러시아인들과 "트럼프 팀" 사이의 관계가 언론에 의해 널리 보도되었습니다.[538][539]

트럼프의 선거운동 관리자 중 한 명인 매너포트는 2004년 12월부터 2010년 2월까지 친러시아 정치인 빅토르 야누코비치가 우크라이나 대통령직을 얻는 것을 돕기 위해 일했습니다.[540] 플린과 스톤을 포함한 다른 트럼프 측근들은 러시아 관리들과 연결되어 있었습니다.[541][542] 유세 도중 러시아 요원들이 매너포트와 플린을 이용해 트럼프에게 영향력을 행사할 수 있다는 말을 엿들었습니다.[543] 트럼프의 선거 운동원들과 이후 그의 백악관 직원들, 특히 플린은 11월 선거 전후에 러시아 관리들과 접촉했습니다.[544][545] 2016년 12월 29일 플린은 세르게이 키슬랴크 러시아 대사와 같은 날 부과된 제재에 대해 이야기를 나눴고, 이후 플린은 펜스 부통령을 오도했는지에 대한 논란 속에 사임했습니다.[546] 트럼프는 2017년 5월 키슬랴크와 세르게이 라브로프에게 러시아의 미국 선거 개입에 대해 우려하지 않는다고 말했습니다.[547]

트럼프와 그의 동맹국들은 러시아가 아닌 우크라이나가 2016년 선거에 개입했다는 음모론을 추진했는데, 이 역시 러시아가 우크라이나를 모함하기 위해 추진한 것입니다.[548] 민주당 전국위원회가 해킹을 당한 후 트럼프는 먼저 FBI로부터 "서버"를 보류했다고 주장했습니다(실제로 140개 이상의 서버가 있었고, 그 중 디지털 사본은 FBI에 주어졌습니다). 둘째, 서버를 조사한 회사인 크라우드스트라이크가 우크라이나에 기반을 두고 우크라이나인 소유였다(실제로 크라우드스트라이크는 미국입니다).-based, 가장 큰 소유주는 미국 회사); 그리고 세 번째로 "서버"가 우크라이나에 숨겨져 있었습니다. 트럼프 행정부의 구성원들은 음모론에 반대하는 목소리를 냈습니다.[549]

FBI 크로스파이어 허리케인과 2017년 방첩 수사

2016년 7월, FBI는 러시아와 트럼프 캠페인 사이의 가능한 연관성에 대한 코드명인 크로스파이어 허리케인 조사를 시작했습니다.[550] 2017년 5월 트럼프가 제임스 코미 FBI 국장을 해임한 후, FBI는 트럼프의 러시아와의 개인 및 사업 거래에 대한 방첩 수사를 시작했습니다.[551] 크로스파이어 허리케인은 [552]뮬러 특검 수사로 넘어갔지만 로드 로젠스타인 법무차관은 뮬러 특검이 이 문제를 추진할 것이라는 잘못된 인상을 주면서 트럼프 대통령과 러시아의 직접적인 관련성에 대한 수사를 종결했습니다.[553][554]

뮬러 수사

2017년 5월 로드 로젠스타인 법무차관은 법무부(DOJ) 특별검사였던 로버트 뮬러 전 FBI 국장을 임명하여 "러시아 정부와 트럼프 캠페인 사이의 모든 연결고리 및/또는 조정"을 검토할 것을 지시했습니다. 그는 뮬러 특검에게 "러시아의 2016년 선거 개입과 관련하여" 형사 문제로 수사를 제한하라고 비공개로 말했습니다.[553] 특검은 또 트럼프가 제임스 코미를 FBI 국장으로 해임한 것이 사법방해에 해당하는지, 트럼프 선거운동이 사우디아라비아와 아랍에미리트, 터키 튀르키예아르, 이스라엘, 중국 등과 연관됐을 가능성도 조사했습니다. 트럼프는 뮬러 특검을 해임하려다 여러 차례 수사를 중단했지만 참모들이 반대하거나 마음을 바꾼 뒤 물러났습니다.[557]

2019년 3월, 뮬러 특검은 수사를 마무리하고 윌리엄 바 법무장관에게 보고서를 제출했습니다.[558] 이틀 후, Barr는 보고서의 주요 결론을 요약하기 위해 의회에 서한을 보냈습니다. 뮬러 특검은 물론 연방 법원도 바가 수사의 결론을 잘못 해석해 대중을 혼란에 빠뜨렸다고 말했습니다.[559][560][561] 트럼프는 반복적으로 거짓으로 수사가 자신의 무죄를 주장했고, 뮬러 보고서는 자신의 무죄를 입증하지 못했다고 명시적으로 밝혔습니다.[562]

2019년 4월에 보고서를 수정한 버전이 공개되었습니다. 러시아가 2016년 트럼프의 출마를 선호하고 클린턴의 출마를 방해하기 위해 개입한 것으로 나타났습니다.[563] 보고서는 "러시아 정부와 트럼프 선거운동 사이의 수많은 연결고리"에도 불구하고 트럼프 선거운동원들이 러시아의 간섭을 공모하거나 조정했다는 지배적인 증거가 "확립되지 않았다"고 밝혔습니다.[564][565] 이 보고서는 러시아의 광범위한 간섭을[565] 드러냈고 트럼프와 그의 선거 운동이 러시아의 노력을 통해 도난당하고 공개된 정보로부터 선거적으로 이익을 얻을 것이라고 믿으면서 어떻게 환영하고 장려했는지 자세히 설명했습니다.[566][567][568][569]

보고서는 또 트럼프의 잠재적 사법방해 행위에 대해서도 상세히 설명했지만 트럼프의 법 위반 여부에 대해서는 '전통적인 검찰 판단'을 하지 않아 의회가 이런 결단을 내려야 한다고 시사했습니다.[570][571] 현직 대통령은 기소할 수 없고,[572] 수사관들은 법정에서 자신의 이름을 밝힐 수 없을 때는 범죄 혐의를 적용하지 않겠다고 법무부 의견으로 밝힌 만큼 수사관들은 "대통령이 범죄를 저질렀다고 판단할 가능성이 있는 접근법을 적용할 수 없다"고 판단했습니다.[573] 보고서는 대통령의 잘못에 대해 조치를 취할 권한을 가진 의회가 "방해법을 적용할 수 있다"고 결론 내렸습니다.[572] 하원은 이후 트럼프-우크라이나 스캔들 이후 탄핵 조사에 착수했지만, 뮬러 특검 수사와 관련한 탄핵 기사는 추진하지 않았습니다.[574][575]

8건의 중범죄 혐의로 유죄를 선고받은 매너포트,[576] 선거운동 부책임자 릭 게이츠,[577] 외교정책 고문 파파도풀로스,[578] 플린 등 뮬러 특검 수사와 관련해 몇몇 트럼프 측근들이 유죄를 인정하거나 유죄를 선고받았습니다.[579][580] 코언은 트럼프가 2016년 러시아와 모스크바에 트럼프 타워를 건설하기 위한 협상을 시도한 것에 대해 의회에 거짓말을 한 것에 대해 유죄를 인정했습니다. 코언은 법정 문서에서 '개인-1'로 확인된 트럼프를 대신해 허위 진술을 했다고 밝혔습니다.[581] 2020년 2월, 스톤은 2016년 선거에서 해킹된 민주당 이메일에 대해 더 자세히 알아보려는 시도와 관련하여 의회에 거짓말을 하고 증인을 조작한 혐의로 40개월의 징역형을 선고받았습니다. 선고 판사는 스톤이 "대통령을 은폐한 혐의로 기소됐다"고 말했습니다.[582]

1차 탄핵

2019년 8월, 내부고발자는 트럼프와 볼로디미르 젤렌스키 우크라이나 대통령 간의 7월 25일 전화 통화에 대해 정보 커뮤니티 감사관에게 불만을 제기했으며, 이 기간 동안 트럼프는 젤렌스키에게 크라우드스트라이크와 민주당 대선 후보 바이든과 그의 아들 헌터를 조사하도록 압력을 가했습니다.[583] 내부고발자는 백악관이 사건을 은폐하려고 시도했으며, 이 통화는 2019년 7월 우크라이나로부터의 재정 지원을 보류하고 펜스의 2019년 5월 우크라이나 여행을 취소하는 것을 포함했을 수 있는 트럼프 행정부와 트럼프 변호사 루디 줄리아니의 광범위한 캠페인의 일부라고 말했습니다.[584]

낸시 펠로시 하원의장은 9월 24일 공식 탄핵조사를 시작했습니다.[585] 이어 트럼프 대통령은 우크라이나에 대한 군사 지원을 보류했다고 확인하면서 상반된 이유를 제시했습니다.[586][587] 9월 25일, 트럼프 행정부는 젤렌스키가 미국산 대전차 미사일 구매를 언급한 후 트럼프가 줄리아니, 바와 함께 바이든과 그의 아들을 조사하는 것에 대해 논의할 것을 요청한 전화 통화 각서를 공개했습니다.[583][588] 복수의 행정부 관리들과 전직 관리들의 증언은 이것이 다가오는 대선에서 트럼프에게 유리한 고지를 제공함으로써 트럼프의 개인적 이익을 증진시키기 위한 광범위한 노력의 일환임을 확인시켜 주었습니다.[589] 10월에 윌리엄 B. 테일러 주니어 우크라이나 담당관은 의회 위원회에서 2019년 6월 우크라이나에 도착한 직후 젤렌스키가 트럼프의 지시와 줄리아니의 주도로 압박을 받고 있다는 사실을 발견했다고 증언했습니다. 테일러 등에 따르면 목표는 2016년 미국 대선에 우크라이나가 개입했다는 소문뿐만 아니라 헌터 바이든을 고용한 회사를 조사하는 공개 약속을 젤렌스키에게 강요하는 것이었습니다.[590] 그는 젤렌스키가 그런 발표를 할 때까지 행정부가 우크라이나에 대한 예정된 군사 지원을 공개하지 않을 것이며 젤렌스키를 백악관으로 초대하지 않을 것임을 분명히 했다고 말했습니다.[591]

12월 13일, 하원 법사위원회는 당론을 따라 투표를 통해 두 개의 탄핵 조항을 통과시켰는데, 하나는 권력 남용과 하나는 의회 방해입니다.[592] 토론 끝에 하원은 12월 18일 두 기사 모두에 대해 트럼프를 탄핵했습니다.[593]

상원 탄핵심판

2020년 1월 재판에서 하원 탄핵소추관들은 사흘 동안 자신들의 사건을 발표했습니다. 이들은 권력 남용과 의회 방해 혐의를 뒷받침할 증거를 들며 트럼프의 행동이 헌법의 탄핵 절차를 만들 때 건국 아버지들이 염두에 둔 것과 똑같다고 주장했습니다.[594]

이후 3일 동안 트럼프의 변호인단은 혐의에 제시된 사실을 부인하지 않았지만 트럼프가 어떤 법도 어기거나 의회를 방해하지 않았다고 말했습니다.[595] 트럼프에게 범죄 혐의가 적용되지 않았기 때문에 탄핵은 "헌법적, 법적으로 무효"라며 권력 남용은 탄핵 가능한 범죄가 아니라고 주장했습니다.[595]

지난 1월 31일 상원은 증인이나 서류에 대한 소환을 허용하는 것에 반대표를 던졌는데, 공화당 의원 51명이 다수를 차지했습니다.[596] 미국 역사상 증인 증언이 없는 탄핵심판은 처음이었습니다.[597]

트럼프는 공화당 다수당에 의해 권력 남용 혐의로 52 대 48, 의회 방해 혐의로 53 대 47로 두 혐의 모두 무죄 판결을 받았습니다. 밋 롬니 상원의원은 공화당에서 유일하게 트럼프에게 한 가지 혐의인 권력 남용에 대해 유죄 판결을 내린 사람입니다.[598] 무죄 판결 이후, 트럼프는 탄핵 증인들과 그가 충분히 충성스럽지 않다고 생각하는 다른 정치적 임명자들과 경력 관리들을 해고했습니다.[599]

2020년 대선

전례를 깨고 트럼프는 대통령직을 맡은 지 몇 시간 만에 FEC에 연임을 신청했습니다.[600] 취임한[601] 지 한 달도 안 돼 첫 재선 집회를 열었고, 2020년 8월 공식적으로 공화당 후보가 됐습니다.[602]

취임 첫 2년 동안 트럼프 재선 위원회는 6,750만 달러를 모았다고 보고했고 현금 1,930만 달러로 2019년을 시작했습니다.[603] 2020년 7월까지 트럼프 캠페인과 공화당은 11억 달러를 모금하고 8억 달러를 지출하여 바이든에 대한 현금 우위를 상실했습니다.[604] 현금 부족으로 인해 캠페인은 광고 지출을 축소해야 했습니다.[605]

트럼프 선거 광고는 바이든이 대통령에 당선되면 도시들이 무법천지로 전락할 것이라고 주장하며 범죄에 초점을 맞췄습니다.[606] 트럼프는 바이든의 입장을[607][608] 반복적으로 잘못 전달하고 인종차별에 대한 호소로 전환했습니다.[609]

2020년 대통령 선거

2020년 봄부터 트럼프는 선거가 조작될 것이며 예상되는 광범위한 우편 투표 사용이 대규모 선거 사기를 일으킬 것이라고 주장하면서 선거에 대한 의구심을 낳기 시작했습니다.[610][611] 지난 7월 트럼프는 선거 연기론을 제기했습니다.[612] 지난 8월 하원이 우편투표 급증을 예상해 미국 우정에 250억 달러의 보조금을 지급하기로 의결하자 트럼프는 우편투표 증가를 막고 싶다며 자금 지원을 차단했습니다.[613] 선거 결과에 승복하고 패배할 경우 평화적 정권교체를 약속할 것인지에 대해서는 거듭 말을 아꼈습니다.[614][615]

바이든은 11월 3일 선거에서 트럼프의 7420만 표([616][617]46.8%)에 8130만 표(51.3%), 트럼프의 232표에 306표(306표)를 얻어 승리했습니다.[618]

투표 부정 허위 주장, 대통령직인수 저지 시도

선거 다음 날 새벽 2시, 결과가 여전히 불투명한 가운데 트럼프는 승리를 선언했습니다.[619] 바이든이 며칠 후 당선자로 예측된 후, 트럼프는 "이번 선거는 끝나지 않았다"고 말했고, 근거 없는 선거 사기 혐의를 받았습니다.[620] 트럼프와 그의 동맹국들은 결과에 대해 많은 법적 이의를 제기했지만, 트럼프가 직접 임명한 연방 판사를 포함하여 주 및 연방 법원 모두에서 최소 86명의 판사가 사실이나 법적 근거를 찾지 못해 기각했습니다.[621][622] 트럼프의 근거 없는 광범위한 투표 사기 혐의에 대해서도 주 선거 관리들은 반박했습니다.[623] 크리스 크렙스 사이버보안 및 인프라 보안국(CISA) 국장이 트럼프의 사기 혐의를 반박하자 트럼프는 11월 17일 그를 해임했습니다.[624] 12월 11일, 미국 대법원은 텍사스 법무장관으로부터 바이든이 승리한 4개 주의 선거 결과를 뒤집으라고 요청한 사건을 심리하기를 거부했습니다.[625]

트럼프는 선거 몇 주 만에 공개 활동에서 손을 뗐습니다.[626] 그는 처음에 정부 관리들이 바이든의 대통령직 인수에 협조하는 것을 막았습니다.[627][628] 3주 후, 총무국의 관리자는 바이든을 선거의 "분명한 승자"로 선언하여 그의 팀에 전환 자원을 지출할 수 있도록 했습니다.[629] 트럼프는 GSA에 전환 프로토콜을 시작할 것을 권고했다고 주장하면서도 여전히 공식적으로 인정하지 않았습니다.[630][631]

선거인단은 12월 14일 바이든의 승리를 공식화했습니다.[618] 트럼프는 지난 11월부터 1월까지 선거 결과를 뒤집기 위해 여러 공화당 지방·주 공직자,[632] 공화당 주·연방 의원,[633] 법무부,[634][635] 펜스 부통령 등을 개인적으로 압박하며 대선인 교체 등 다양한 행동을 촉구했습니다. 또는 조지아주 공무원들이 투표를 "찾고" "재계산된" 결과를 발표해 줄 것을 요청할 수도 있습니다.[633] 2021년 2월 10일, 조지아 검찰은 조지아에서 선거를 전복시키려는 트럼프의 노력에 대한 범죄 수사를 시작했습니다.[636]

트럼프는 몇 시간 전 워싱턴을 떠나 플로리다로 향하는 바이든 당선인의 취임식에 참석하지 않았습니다.[637]

쿠데타 시도 또는 군사적 조치 가능성에 대한 우려

2020년 12월, 뉴스위크는 국방부가 적색경보를 발령했고, 고위 관리들은 트럼프가 계엄령을 선포하기로 결정하면 어떻게 할 것인지 논의했다고 보도했습니다. 국방부는 국방부 지도자들의 말을 인용해 군이 선거 결과에서 할 역할이 없다고 답했습니다.[638]

2020년 11월 선거 이후 트럼프가 지지자들을 국방부의 권력 위치로 이동시켰을 때, 마크 밀리 합참의장과 지나 해스펠 CIA 국장은 중국이나 이란에 대한 쿠데타 시도나 군사 행동의 위협에 대해 우려하게 되었습니다.[639][640] 밀리는 핵무기 사용을 포함한 트럼프의 군사 명령에 대해 자문을 받아야 한다고 주장했고, 해스펠과 폴 나카소네 NSA 국장에게 상황을 면밀히 관찰하라고 지시했습니다.[641][642]

1월 6일 국회의사당 공격

2021년 1월 6일, 미국 국회의사당에서 대통령 선거 결과에 대한 의회 인증이 진행되는 동안, 트럼프는 워싱턴 D.C.의 타원에서 정오 집회를 열었습니다. 그는 선거 결과를 뒤집을 것을 촉구하고 지지자들에게 "힘을 보여달라", "지옥처럼 싸우라"며 의사당까지 행진해 "우리나라를 되찾으라"고 촉구했습니다.[643][644] 많은 지지자들이 이미 거기에 있는 군중에 합류했습니다. 오후 2시 15분경 폭도들이 건물에 침입해 인증을 방해하고 의회가 대피하는 소동이 벌어졌습니다.[645] 폭력 사태가 벌어지는 동안 트럼프는 폭도들에게 해산을 요구하지 않고 TV를 시청하고 트위터에 글을 올렸습니다. 트럼프는 오후 6시 트위터를 통해 폭도들을 "위대한 애국자", "매우 특별하다"고 부르며 선거가 자신에게서 빼앗긴 것이라고 거듭 강조했습니다.[646] 의회는 폭도들이 의사당에서 철거된 뒤 다음날 새벽 바이든 당선인의 당선을 재소집해 확정했습니다.[647] 법무부에 따르면 경찰관 140여 명이 다쳤고, 5명이 숨졌습니다.[648][649]

2023년 3월, 트럼프는 수감된 폭도들과 함께 수감자들에게 혜택을 주기 위한 노래를 공동 작업했고, 6월에는 당선되면 많은 수의 수감자들을 사면하겠다고 말했습니다.[650]

2차 탄핵

2021년 1월 11일, 트럼프에게 미국 정부에 대한 반란 선동을 고발하는 탄핵 기사가 하원에 제출되었습니다.[651] 하원은 1월 13일 트럼프를 232 대 197로 탄핵했고, 트럼프는 두 번 탄핵당한 최초의 미국 대통령이 되었습니다.[652] 10명의 공화당원들이 탄핵에 투표했는데, 이는 당의 대통령을 탄핵하기 위해 투표한 사상 가장 많은 당원들입니다.[653]

2월 13일, 5일간의 상원 재판 이후, 트럼프는 상원이 유죄 판결을 위해 필요한 3분의 2의 과반수에 10표 모자라는 57대 43으로 투표했을 때 무죄 판결을 받았습니다. 7명의 공화당 의원들이 모든 민주당 의원들과 함께 유죄 판결을 위한 투표에 참여했는데, 이는 대통령이나 전직 대통령에 대한 상원 탄핵 재판 중 가장 초당적인 지지를 받은 것입니다.[654][655] 일부는 트럼프에게 책임을 묻지만 상원이 전직 대통령에 대한 관할권을 가지고 있지 않다고 느꼈지만, 대부분의 공화당원들은 트럼프에게 무죄를 선고하기로 투표했습니다(트럼프는 1월 20일에 퇴임했습니다; 상원은 56대 44로 재판이 합헌이라고 투표했습니다).[656] 후자의 그룹에는 미치 매코널이 포함되었습니다.[657]

사장직(2021~현재)

임기가 끝나갈 무렵 트럼프는 자신의 마라라고 클럽에서 살게 됐습니다.[658] 전직 대통령법에 규정된 [659]대로 그 곳에 사무실을 설치해 대통령 이후의 활동을 처리했습니다.[659][660]

2020년 선거와 관련된 트럼프의 거짓 주장은 언론과 그를 비판하는 사람들에 의해 일반적으로 "큰 거짓말"로 언급되었습니다. 2021년 5월, 트럼프와 그의 지지자들은 이 용어를 선거 자체를 지칭하는 데 사용하여 공동 채택을 시도했습니다.[661][662] 공화당은 트럼프의 거짓 선거 서술을 이용해 자신에게 유리한 새로운 투표 제한을 부과하는 것을 정당화했습니다.[662][663] 2022년 7월까지 트럼프는 여전히 바이든에 대한 주 선거인단 투표를 철회함으로써 2020년 선거를 뒤집으라고 주 의원들에게 압력을 가하고 있었습니다.[664]

트럼프는 2021년 6월 6일 연례 노스캐롤라이나 공화당 전당대회에서 85분 연설로 선거운동 방식의 집회를 재개했습니다.[665][666] 6월 26일, 그는 국회의사당에서 폭동에 앞서 열린 1월 6일 집회 이후 첫 공개 집회를 열었습니다.[667]

다른 전직 대통령들과 달리 트럼프는 그의 당을 계속 지배했습니다; 그는 현대의 당 보스로 묘사되었습니다. 그는 공화당보다 두 배 이상 많은 모금을 계속했고, 세 번째 출마를 시사했으며, 마라라고에서 열린 많은 공화당 후보들의 모금 행사로 이익을 얻었습니다. 그의 초점은 선거가 어떻게 운영되는지와 2020년 선거 결과를 뒤집으려는 그의 시도에 저항한 선거 관리자들을 축출하는 것이었습니다. 2022년 중간 선거에서 그는 200명이 넘는 다양한 직책의 후보자들을 지지했는데, 그들 대부분은 2020년 대선이 그에게서 도난당했다는 그의 거짓 주장을 지지했습니다.[668][669][670]

2021년 2월, 트럼프는 미국 고객에게 "소셜 네트워킹 서비스"를 제공하는 새로운 회사인 트럼프 미디어 & 테크놀로지 그룹(TMTG)을 등록했습니다.[671][672] TMTG는 2024년 3월 특수목적 인수회사 디지털월드어퀴지션과 합병해 공기업이 됐습니다.[673]

2022년 2월, TMTG는 소셜 미디어 플랫폼인 Truth Social을 출시했습니다.[674] 2023년[update] 3월 현재 러시아 관련 기업으로부터 800만 달러를 빼앗은 트럼프 미디어는 자금 세탁 가능성으로 연방 검찰의 수사를 받고 있습니다.[675][676]

수사, 형사고발, 민사소송

트럼프는 그의 대통령직 전후에 그의 행동과 사업 거래에 대한 수많은 조사의 대상입니다.[677] 2021년 2월 조지아주 풀턴 카운티의 지방 검사인 패니 윌리스는 트럼프가 조지아주 국무장관 브래드 래펜스퍼거에게 전화를 건 것에 대한 범죄 수사를 발표했습니다.[678] 뉴욕주 검찰총장실은 맨해튼 지방검찰청과 연계해 트럼프 대통령의 기업 활동에 대한 범죄 수사를 벌이고 있습니다.[679] 2021년 5월까지 특별 대배심은 기소를 고려하고 있었습니다.[680][681] 2021년 7월, 뉴욕 검찰은 트럼프 조직에 "정부를 사취하는 15년 계획"을 적용했습니다.[682] 2023년 1월, 이 기관의 최고 재무 책임자인 알렌 바이셀버그(Allen Weisselberg)는 유죄 판결 후 세금 사기 혐의로 징역 5개월에 집행유예 5년을 선고받았습니다.[683]

FBI 수사

트럼프는 2021년 1월 백악관을 떠날 때 마라라고에 정부 문서와 자료를 가져갔습니다. 2021년 5월까지, 정부 기록물을 보존하는 연방 기관인 국가기록물관리국(NARA)은 중요한 문서가 트럼프 대통령 임기 말에 반환되지 않았음을 깨닫고, 그의 사무실에 문서의 위치를 요청했습니다. 2022년 1월, 그들은 마라라고에서 백악관 기록 15박스를 회수했습니다. NARA는 이후 회수된 문서 중 일부가 기밀 자료라고 법무부에 알렸습니다.[684] 법무부는 2022년 4월부터 조사를 시작해 대배심을 소집했습니다.[685] 법무부는 지난 5월 11일 트럼프 대통령에게 추가 자료에 대한 소환장을 보냈습니다.[684] 6월 3일, 법무부 관리들은 마라라고를 방문했고 트럼프의 변호사들로부터 몇 가지 기밀 문서들을 받았습니다.[684] 변호인 중 한 명은 기밀로 표시된 모든 자료가 정부에 반환되었음을 확인하는 성명서에 서명했습니다.[686] 그 달 말에 Mar-a-Lago로부터 감시 영상을 요청하는 추가 소환장이 발송되었고, 그것은 제공되었습니다.[684][687][688]

2022년 8월 8일, FBI 요원들은 트럼프가 대통령기록법을 위반하고 퇴임할 때 가지고 간 정부 문서와 자료를 복구하기 위해 마러라고에 있는 트럼프의 주거지와 사무실, 저장고 등을 수색했는데,[689][690] 여기에는 핵무기와 관련된 것들도 포함된 것으로 알려졌습니다.[688] 미국 법무장관 메릭 갈랜드가 승인하고 연방 치안 판사가 승인한 수색 영장과 압수품 목록이 8월 12일 공개되었습니다. 압수수색 영장의 문안에는 간첩법 위반과 사법방해 가능성에 대한 수사가 적시돼 있습니다.[691] 검색에 찍힌 항목에는 11개의 기밀 문서 세트가 포함되어 있는데, 이 중 4개는 "일급 기밀", 1개는 "일급 기밀/SCI"로 분류되어 가장 높은 수준의 분류입니다.[689][690]

2022년 11월 18일 갈랜드는 특별 검사인 잭 스미스를 임명하여 트럼프가 마라라고에 정부 재산을 보유하고 2021년 1월 6일 국회의사당 공격으로 이어지는 사건에서 트럼프의 역할을 조사하는 연방 범죄 수사를 감독했습니다.[692][693]

하원 1월 6일 위원회의 형사 회부

2022년 12월 19일, 미국 하원 1·6 공격 선정 위원회는 트럼프 대통령에게 공식 절차 방해, 미국 편취 음모, 반란을 선동하거나 방조한 혐의로 형사 고발을 권고했습니다.[694]

트럼프에 대한 연방 및 주 형사 사건

사업 기록을 위조한 혐의로 뉴욕 검찰

2023년 3월 30일, 뉴욕 대배심은 업무 기록을 위조한 34건의 중범죄 혐의로 트럼프를 기소했습니다.[695][696] 4월 4일, 그는 항복하고 체포되어 체포되어 체포되었고, 모든 혐의에 대해 무죄를 주장하고 풀려났습니다.[697] 재판은 2024년 3월 25일에 시작될 예정입니다.[698]

정부 및 기밀문서 사례

6월 8일, 법무부는 마이애미 연방 법원에서 트럼프를 31건의 "간첩법에 따라 국방 정보를 고의로 보관"한 혐의, 허위 진술을 한 혐의, 그리고 개인 보좌관과 공동으로 사법 방해 음모, 정부 문서 보류, 부패한 기록 은폐 혐의로 기소했습니다. 연방 수사에서 문서를 숨기고 그들의 노력을 숨기려고 계획하는 것입니다.[699] 트럼프는 모든 혐의에 대해 무죄를 주장했습니다.[700] 지난 7월 기소유예로 인해 3건의 범죄 혐의가 추가되어 사건의 혐의 수는 40건이 되었습니다.[701] 재판은 2024년 5월 20일에 시작될 예정입니다.[698]

선거방해사건

8월 1일, 워싱턴 D.C. 연방 대배심은 2020년 선거 결과를 뒤집으려는 트럼프의 노력에 대해 네 가지 혐의로 기소했습니다. 그는 이름이 알려지지 않은 공모자들과 공모하여 미국을 사취하고, 선거인단 투표의 인증을 방해하고, 사람들이 개표할 수 있는 시민의 권리를 박탈하고, 공식 절차를 방해한 혐의로 기소되었습니다.[702] 트럼프는 무죄를 주장했습니다.[703]

조지아 선거 개입 사건

8월 14일, 조지아주 풀턴 카운티의 대배심은 트럼프 선거 운동 관계자들이 선거 관계자들과 함께 투표 기계에 접속한 후 다른 중범죄들 중에서도 13개의 혐의로 트럼프를 기소했습니다.[704][705] 8월 24일, 트럼프는 항복했고, 체포되어 풀턴 카운티 교도소에서 처리되었다가 보석으로 풀려났습니다. 그는 트위터와 캠페인 웹사이트에 모금 글과 함께 머그 샷을 올렸습니다.[706] 8월 31일, 그는 무죄를 주장했습니다.[707] 2024년 3월 13일, 판사는 트럼프에 대한 13건의 혐의 중 3건을 "혐의와 관련된 과잉 행위"를 기각하지 않고 기각했습니다.[708]

트럼프에 대한 민사소송

뉴욕주의 민사 사기 사건

2022년 9월, 뉴욕 주 법무장관은 트럼프와 그의 세 자녀, 그리고 트럼프 조직을 상대로 민사 사기 사건을 제기했습니다.[709] 2021년 12월, 법무장관실은 트럼프를 소환하여 그의 사업과 관련된 문서를 작성했습니다.[710] 2022년 4월, 뉴욕 주 판사는 트럼프가 소환장에 불응한 것에 대해 법정 모독죄로 잡고, 그가 불응할 때까지 하루에 1만 달러의 벌금을 부과했습니다.[711] 트럼프는 지난 8월 자신의 수정헌법 5조를 400번 넘게 발동하며 폐위됐습니다.[712] 민사 소송을 재판하는 판사는 2023년 9월 트럼프와 그의 성인 아들, 트럼프 조직이 반복적으로 사기를 저질러 뉴욕 사업자 증명서를 취소하고 사업 주체를 해산을 위해 경영진에 보내도록 명령했다고 판결했습니다.[713]

2024년 2월, 법원은 트럼프의 책임을 인정하고, 총 4억 5천만 달러를 초과하는 3억 5천만 달러 이상의 벌금과 이자를 지불하도록 명령했으며, 3년 동안 뉴욕 법인 또는 법인의 임원이나 이사로 재직할 수 없도록 금지했습니다. 트럼프는 판결에 항소하겠다고 밝혔습니다. 판사는 또한 2023년 법원이 임명한 모니터와 독립적인 준법 이사가 회사를 감독하고 "구조조정 및 잠재적 해산"은 모니터의 결정에 따를 것을 명령했습니다.[714]

E. 진 캐롤의 소송

2023년 5월, 뉴욕 배심원단은 기자 E. 진 캐롤이 제기한 연방 소송에서 트럼프가 성적 학대와 명예훼손에 책임이 있다고 판단하고 그녀에게 500만 달러를 지불하라고 명령했습니다.[715] 트럼프는 배심원단이 자신에게 강간죄의 책임을 인정하지 않았다고 주장하며 지방법원에 새로운 재판이나 피해액 감경을 요청했고, 별도의 소송에서 캐롤을 명예훼손으로 맞섰습니다. 두 소송의 판사는 7월과 8월에 트럼프에게 불리한 판결을 내렸습니다.[716][717] 트럼프는 두 결정 모두 항소 법원에 항소했습니다.[716][718] 2024년 1월 26일, 명예훼손 사건의 배심원단은 트럼프에게 캐롤에게 8330만 달러의 손해배상금을 지급하라고 명령했습니다. 트럼프는 판결에 항소하겠다고 밝혔습니다.[719]

2024년 대통령 선거

2022년 11월 15일, 트럼프는 2024년 미국 대통령 선거 출마를 선언하고 모금 계좌를 만들었습니다.[720][721] 2023년 3월, 캠페인은 기부금의 10%를 2023년 6월까지 그의 법적 청구서를 위해 1,600만 달러를 지불한 트럼프의 지도부 PAC에 돌리기 시작했습니다.[722]

2023년 12월 콜로라도 대법원은 2024년 3월 미국 대법원이 트럼프 대 앤더슨 판결을 파기할 때까지 트럼프의 재임 자격이 박탈되었다고 판결했습니다.[723]

공공이미지

학술평가 및 국민승인조사

C-SPAN은 2021년 대통령 역사 조사에서 트럼프를 전체 4번째로 낮은 순위에 올렸고, 트럼프는 도덕적 권위와 행정 기술에서 리더십 특성 항목에서 가장 낮은 순위를 받았습니다.[1][724][725] 시에나 대학 연구소의 2022년 조사는 트럼프를 45명의 대통령 중 43위로 평가했습니다. 배경, 청렴도, 정보력, 외교정책 성과, 임원 인사 등에서 꼴찌를 기록했고, 타협 능력, 임원 능력, 전체적인 견해 제시 등에서 두 번째로 꼴찌를 기록했습니다. 운, 위험 감수 의지, 당 지도부를 제외한 모든 항목에서 최하위권에 가까웠습니다.[2]

1938년까지의 갤럽 여론조사에서 트럼프는 50%의 지지율에 도달하지 못한 유일한 대통령이었습니다. 그의 지지율은 공화당에서 88퍼센트, 민주당에서 7퍼센트로 사상 최고의 당파적 격차를 보였습니다.[726] 2020년 9월까지 시청률은 최고 49%, 최저 35%를 기록하며 이례적으로 안정적이었습니다.[727] 트럼프는 29%에서 34% 사이의 지지율로 임기를 마쳤습니다. 이는 현대 여론조사가 시작된 이래 가장 낮은 수치입니다. 그리고 대통령 재임 기간 내내 41%라는 사상 최저의 평균을 기록했습니다.[726][728]

미국인들에게 가장 존경하는 남자의 이름을 지어달라고 요청하는 갤럽의 연례 여론조사에서 트럼프는 2017년과 2018년에 오바마에 이어 2위를 차지했고, 2019년에는 오바마와 동률을 이뤘고, 2020년에는 1위를 차지했습니다.[729][730] 1948년 갤럽이 여론조사를 실시하기 시작한 이래, 트럼프는 취임 첫 해에 가장 존경받는 대통령으로 선정되지 않은 첫 번째 선출된 대통령입니다.[731]

갤럽이 지난 2016~2017년 미국 지도부 지지율을 비교한 134개국 여론조사에서 트럼프가 오바마를 앞섰고, 대부분 비민주국가인 29개국에서만 취업 승인이 줄었고,[732] 동맹국과 G7 국가에서는 미국 지도부 지지율이 급락했습니다. 전반적인 평가는 조지 W. 부시 대통령의 지난 2년 동안의 평가와 비슷했습니다.[733] 2020년 중반까지 13개국으로 구성된 퓨 리서치 여론조사에 대한 국제 응답자의 16%만이 트럼프에 대한 신뢰를 표명했으며, 이는 러시아의 블라디미르 푸틴과 중국의 시진핑보다 낮았습니다.[734]

거짓 또는 오해의 소지가 있는 진술

후보로서 그리고 대통령으로서 트럼프는 미국 정치에서 전례가 없을 정도로 공개 발언에서[161][157] 거짓 발언을 자주 했습니다.[738][739] 그의 거짓은 그의 정치적 정체성의 독특한 부분이 되었습니다.[738]

워싱턴 포스트를 포함한 팩트 체커들은 트럼프가 4년 임기 동안 한 30,573건의 거짓 또는 오해의 소지가 있는 진술을 기록했습니다.[735] 트럼프의 거짓은 시간이 지남에 따라 빈도가 증가하여 대통령 취임 첫 해에는 하루에 약 6건의 거짓 또는 오해의 소지가 있는 주장에서 두 번째 해에는 하루에 16건, 세 번째 해에는 하루에 22건, 마지막 해에는 39건으로 증가했습니다.[740]

트럼프의 거짓 중 일부는 중요하지 않았습니다. 예를 들어, "사상 최대의 취임식 군중"이라고 주장했습니다.[741][742] 다른 것들은 그가 COVID-19 치료제로 입증되지 않은 말라리아 치료제를 홍보하는 등 더 광범위한 영향을 미쳤고,[743][744] 미국에서 이러한 약의 부족을 초래하고 아프리카와 남아시아에서 공황 구매를 하는 등의 효과를 거두었습니다.[745][746] 잉글랜드와 웨일스의 범죄 증가를 "급진적인 이슬람 테러의 확산"으로 잘못 돌리는 것과 같은 다른 잘못된 정보는 트럼프의 국내 정치적 목적에 도움이 되었습니다.[747] 원칙적으로 트럼프는 자신의 거짓에 대해 사과하지 않습니다.[748]

트럼프의 거짓말이 빈발하고 있음에도 불구하고 언론은 거짓말이라고 거의 언급하지 않았습니다.[749][750] 워싱턴 포스트가 그렇게 한 것은 2018년 8월로, 스토미 대니얼스와 플레이보이 모델 캐런 맥두걸에게 지급된 쉬쉬머니에 대한 트럼프의 잘못된 진술 중 일부가 거짓말이라고 선언했을 때였습니다.[751][750]

2020년 트럼프는 우편 투표와 COVID-19 팬데믹에 대한 중요한 허위 정보원이었습니다.[752][753] 우편 투표용지와 기타 선거 관행에 대한 공격은 2020년 대선의 진실성에 대한 대중의 신뢰를 약화시키는 반면,[754][755] 팬데믹에 대한 잘못된 정보는 팬데믹에 대한 국가적 대응을 지연시키고 약화시켰습니다.[450][752]

조지 메이슨 대학의 정책 및 정부 교수인 제임스 피프너는 2019년에 트럼프가 "잘 알려진 사실에 명백하게 반하는 터무니없는 거짓 진술"을 제공하기 때문에 이전 대통령들과 다르게 거짓말을 한다고 썼습니다. 이러한 거짓말은 트럼프의 모든 거짓말 중 "가장 중요한" 것입니다. 사실에 의문을 제기함으로써 사람들은 "정치 권력"에 의해 비합리적으로 해결된 신념이나 정책으로 자신의 정부를 제대로 평가할 수 없게 될 것입니다. 이것은 자유 민주주의를 약화시킨다고 피프너는 썼습니다.[756]

음모론 추진

트럼프는 대통령직을 전후해 오바마 친생자주의, 클린턴 몸개그 음모론, 음모론 운동 QAnon, 지구온난화 거짓말론, 트럼프 타워 도청 의혹, 존 F 등 수많은 음모론을 추진했습니다. 라파엘 크루즈가 관련된 케네디 암살 음모론은 토크쇼 진행자 조 스카버러를 스태프 사망과 연관시켰으며,[757] 안토닌 스캘리아 대법관의 사망에 대한 반칙 혐의, 우크라이나의 미국 선거 개입 의혹, 오사마 빈 라덴이 살아 있었고 오바마와 바이든은 네이비실 6팀 멤버들이 사망했다고 주장했습니다.[758][759][760][761][762] 트럼프는 적어도 두 번은 문제의 음모론을 믿는다고 언론에 분명히 했습니다.[760]

트럼프는 2020년 대선 기간과 이후 사망자 투표,[763] 기표기 변경 또는 삭제, 부정 우편 투표, 트럼프 표 던지기, 바이든 표로 가득한 여행 가방 찾기 등 자신의 패배에 대한 다양한 음모론을 추진해 왔습니다.[764][765]

폭력의 선동

연구에 따르면 트럼프의 수사는 증오 범죄의 발생률을 높였습니다.[766][767] 그는 2016년 선거운동 기간 동안 시위대나 기자들에 대한 물리적 공격을 촉구하거나 칭찬했습니다.[768][769] 2021년 1월 6일 미국 국회의사당을 습격한 참가자들을 포함하여 수많은 피고인들이 폭력 행위와 증오 범죄로 수사하거나 기소되었으며, 트럼프의 수사를 인용하여 그들에게 책임이 없거나 선처를 받아야 한다고 주장했습니다.[770][771] 2020년 5월 ABC 뉴스의 전국적인 리뷰에 따르면 2015년 8월부터 2020년 4월까지 트럼프가 주로 백인 남성과 주로 소수자에 대한 폭력 또는 폭력 위협과 직접적으로 관련되어 발동된 최소 54건의 형사 사건이 확인되었습니다.[772]

소셜 미디어

트럼프의 소셜 미디어 존재는 2009년 트위터에 합류한 후 전 세계적인 관심을 끌었습니다. 그는 2016년 선거 운동 기간 동안 그리고 임기 마지막 날 트위터가 그를 금지할 때까지 대통령으로서 자주 트위터에 글을 올렸습니다.[773] 트럼프는 대중과 직접 소통하고 언론을 따돌리기 위해 종종 트위터를 사용했습니다.[774] 2017년 6월, 백악관 대변인은 트럼프의 트윗이 공식적인 대통령 성명이라고 말했습니다.[775] 트럼프는 종종 트위터를 통해 행정부 관리들의 종료를 발표했습니다.[776]

트럼프가 잘못된 정보와 거짓을 게시하도록 허용한 것에 대해 수년간 비판을 받은 후, 트위터는 2020년 5월에 그의 트윗 중 일부에 팩트체크 경고를 태그하기 시작했습니다.[777] 이에 트럼프는 트위터를 통해 "소셜 미디어 플랫폼은 보수적인 목소리를 완전히 침묵시킨다"며 "강력하게 규제하거나 폐쇄하겠다"고 밝혔습니다.[778] 의사당 습격 사건 이후 며칠 동안 트럼프는 페이스북, 인스타그램, 트위터 및 기타 플랫폼에서 금지되었습니다.[779] 그의 소셜 미디어 존재감의 상실은 사건을[780][781] 형성하는 능력을 감소시켰고 트위터에서 공유되는 잘못된 정보의 양을 극적으로 감소시켰습니다.[782] 트럼프가 초기에 시도한 소셜 미디어의 존재감 회복은 성공적이지 못했습니다.[783] 2022년 2월, 그는 자신의 트위터 팔로워의 일부만을 끌어모았던 소셜 미디어 플랫폼 트루스 소셜을 출시했습니다.[784] 2022년 11월 트위터의 새로운 소유자인 엘론 머스크는 트럼프의 트위터 계정을 복원했습니다.[785]

언론과의 관계

트럼프는 언론과의 "애증" 관계를 유지하면서 자신의 경력 내내 언론의 관심을 구했습니다.[786] 2016년 선거운동에서 트럼프는 기록적인 양의 무료 언론 보도로 인해 공화당 예비선거에서 자신의 입지를 높였습니다.[154] 뉴욕타임스 작가 에이미 초직은 2018년 트럼프의 미디어 지배력이 대중을 매료시키고 "꼭 봐야 할 TV"를 만들었다고 썼습니다.[787]

후보로서 그리고 대통령으로서 트럼프는 언론을 "가짜 뉴스 미디어", "국민의 적"이라고 부르며 자주 편견을 비난했습니다.[788] 2018년 저널리스트 레슬리 스탈은 트럼프가 의도적으로 언론을 불신했다고 말한 것에 대해 "그래서 당신이 나에 대해 부정적인 이야기를 쓸 때 아무도 당신을 믿지 않을 것"이라고 말했습니다.[789]

트럼프는 대통령으로서 자신이 비판적이라고 생각하는 언론인들의 언론 자격을 취소하는 것에 대해 고민했습니다.[790] 그의 행정부는 법원에 의해 복구된 두 명의 백악관 기자들의 언론 통과를 취소하려고 했습니다.[791] 트럼프 백악관은 2017년에 약 100건의 공식 언론 브리핑을 개최했으며, 2018년에는 절반으로 감소했으며 2019년에는 2건으로 감소했습니다.[791]

트럼프는 언론을 겁박하기 위해 법적 시스템도 배치했습니다.[792] 2020년 초, 트럼프 캠페인은 뉴욕 타임즈, 워싱턴 포스트, CNN을 러시아 선거 개입에 대한 의견으로 명예훼손으로 고소했습니다.[793][794] 법률 전문가들은 이 소송들이 메리트가 부족하고 성공할 가능성이 낮다고 말했습니다.[792][795] 2021년 3월까지 뉴욕 타임즈와 CNN을 상대로 한 소송은 기각되었습니다.[796][797]

인종관

트럼프의 많은 발언과 행동은 인종차별로 여겨져 왔습니다.[798][799] 전국 여론조사에서 응답자의 약 절반이 트럼프가 인종차별주의자라고 답했습니다. 그가 인종차별주의자들을 대담하게 만들었다고 믿는 비율이 더 높았습니다.[800][801] 여러 연구와 설문조사에서 인종차별적 태도가 트럼프의 정치적 부상을 부추겼고, 트럼프 유권자의 충성도를 결정하는 데 경제적 요인보다 더 중요한 것으로 나타났습니다.[802][803] 인종차별적이고 이슬람 혐오적인 태도는 트럼프를 지지하는 강력한 지표입니다.[804]

1975년, 그는 흑인 임차인에 대한 주거 차별을 주장하는 1973년 법무부 소송을 해결했습니다.[49] 그는 또한 흑인과 라틴계 10대들이 2002년 DNA 증거에 의해 무죄가 선고된 후에도 1989년 센트럴 파크 조깅 사건에서 백인 여성을 강간한 혐의로 인종 차별 혐의를 받고 있습니다. 2019년 현재 이 자리를 유지하고 있습니다.[805]

2011년, 그가 대선 출마를 고려하고 있다는 보도가 나왔을 때, 그는 인종차별적인 "출산" 음모론의 주요 지지자가 되었고, 미국 최초의 흑인 대통령인 버락 오바마가 미국에서 태어나지 않았다고 주장했습니다.[806][807] 4월에, 그는 백악관이 "긴 형태의" 출생 증명서를 출판하도록 압력을 가한 것에 대한 공을 주장했습니다. 그가 사기꾼이라고 여겼으며, 나중에 이 일이 그를 "매우 인기 있게" 만들었다고 말했습니다.[808][809] 2016년 9월, 압박 속에, 그는 오바마가 미국에서 태어났다는 것을 인정했습니다.[810] 2017년에, 그는 사적으로 형제의 견해를 표현했다고 합니다.[811]

정치학 계간지의 분석에 따르면 트럼프는 2016년 대선 캠페인 기간 동안 "명백인들에게 노골적으로 인종차별적인 호소를 했다"고 합니다.[812] 특히 그의 선거출범 연설은 멕시코 이민자들이 "약물을 가져오고, 범죄를 가져오고, 강간자들"이라고 주장해 광범위한 비판을 받았습니다.[813][814] 멕시코계 미국인 판사가 트럼프 대학과 관련한 민사소송을 주재했다는 그의 이후 발언도 인종차별적이라는 비판을 받았습니다.[815]

트럼프가 2017년 우파 연합 집회에서 "여러 측면에서 증오, 편협함, 폭력의 이 말도 안 되는 과시"를 비난하고 "양쪽에 매우 훌륭한 사람들이 있다"고 말한 것은 백인 우월주의 시위대와 반대 시위대 사이의 도덕적 동등성을 암시하는 것으로 널리 비판받았습니다.[816][817][818][819]

트럼프 대통령은 2018년 1월 이민법 논의에서 엘살바도르, 아이티, 온두라스, 아프리카 국가들을 "시톨 국가"라고 지칭한 것으로 알려졌습니다.[820] 그의 발언은 인종차별주의자로 비난 받았습니다.[821][822]

2019년 7월, 트럼프는 트위터를 통해 4명의 민주당 하원의원(모두 소수민족 출신, 그 중 3명은 미국 태생)이 "출신" 국가로 "돌아가야 한다"고 말했습니다.[823] 이틀 후 하원은 그의 "인종차별적 발언"을 비난하기 위해 240 대 187로 투표했습니다.[824] 백인 민족주의 출판물과 소셜 미디어는 그의 발언에 찬사를 보냈으며, 이 발언은 이후 며칠 동안 계속되었습니다.[825] 트럼프는 2020년 선거운동 기간에도 비슷한 발언을 계속했습니다.[826]

여성혐오 및 성비위 혐의

트럼프는 언론과 소셜미디어에서 연설할 때 여성을 모욕하고 경시한 전력이 있습니다.[827][828] 음담패설을 하고, 여성의 신체적 외모를 비하하고, 경멸적인 표현을 사용하여 언급했습니다.[828][829][830] 최소 26명의 여성들이 트럼프를 강간하고, 키스하고, 동의 없이 더듬고, 여성들의 치마 밑을 들여다보고, 벌거벗은 10대 미인대회 참가자들에게 걸어 들어갔다고 공개적으로 비난했습니다.[831][832][833] 트럼프는 모든 혐의를 부인했습니다.[833]

두 번째 대선 토론회를 이틀 앞둔 2016년 10월, 트럼프가 동의 없이 여성들에게 키스하고 더듬는 모습을 자랑하는 2005년 '핫 마이크' 녹화가 수면 위로 떠올랐습니다. "당신이 스타일 때, 그들은 당신이 그것을 하도록 내버려 둡니다. 당신은 무엇이든 할 수 있습니다... 그들의 여자를 잡아라."[834] 이 사건의 광범위한 언론 노출은 선거 운동[835] 기간 동안 트럼프의 첫 공개 사과로 이어졌고 정치권 전반에 걸쳐 분노를 불러일으켰습니다.[836]

대중문화

트럼프는 텔레비전, 영화, 만화에서 코미디와 캐리커처의 주제가 되어 왔습니다. 그는 1989년부터 2015년까지 수백 곡의 힙합 곡에 이름을 올렸습니다. 이 곡들 중 대부분은 긍정적인 관점에서 트럼프를 캐스팅했지만, 그가 출마하기 시작한 후 대부분 부정적으로 바뀌었습니다.[837]

메모들

참고문헌

- ^ a b Sheehey, Maeve (June 30, 2021). "Trump debuts at 41st in C-SPAN presidential rankings". Politico. Retrieved March 31, 2023.

- ^ a b "American Presidents: Greatest and Worst". Siena College Research Institute. June 22, 2022. Retrieved July 11, 2022.

- ^ "Certificate of Birth". Department of Health – City of New York – Bureau of Records and Statistics. Archived from the original on May 12, 2016. Retrieved October 23, 2018 – via ABC News.

- ^ "Trump's parents and siblings: What do we know of them?". BBC News. October 3, 2018. Retrieved February 15, 2021.

- ^ Kranish & Fisher 2017, p. 33.

- ^ Horowitz, Jason (September 22, 2015). "Donald Trump's Old Queens Neighborhood Contrasts With the Diverse Area Around It". The New York Times. Retrieved November 7, 2018.

- ^ Kranish & Fisher 2017, 페이지 38.

- ^ "Two Hundred and Twelfth Commencement for the Conferring of Degrees" (PDF). University of Pennsylvania. May 20, 1968. pp. 19–21. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 19, 2016. Retrieved March 31, 2023.

- ^ Viser, Matt (August 28, 2015). "Even in college, Donald Trump was brash". The Boston Globe. Retrieved May 28, 2018.

- ^ Ashford, Grace (February 27, 2019). "Michael Cohen Says Trump Told Him to Threaten Schools Not to Release Grades". The New York Times. Retrieved June 9, 2019.

- ^ Montopoli, Brian (April 29, 2011). "Donald Trump avoided Vietnam with deferments, records show". CBS News. Retrieved July 17, 2015.

- ^ – "Donald John Trump's Selective Service Draft Card and Selective Service Classification Ledger". National Archives. March 14, 2019. Retrieved September 23, 2019. 정보자유법(FOIA)을 통해

- ^ Whitlock, Craig (July 21, 2015). "Questions linger about Trump's draft deferments during Vietnam War". The Washington Post. Retrieved April 2, 2017.

- ^ Eder, Steve; Philipps, Dave (August 1, 2016). "Donald Trump's Draft Deferments: Four for College, One for Bad Feet". The New York Times. Retrieved August 2, 2016.

- ^ 블레어 2015, 300쪽.

- ^ "Ivana Trump becomes U.S. citizen". The Lewiston Journal. Associated Press. May 27, 1988. p. 10D. Retrieved August 21, 2015 – via Google web.

- ^ Baron, James (December 12, 1990). "Trumps Get Divorce; Next, Who Gets What?". The New York Times. Retrieved March 5, 2023.

- ^ Hafner, Josh (July 19, 2016). "Get to know Donald's other daughter: Tiffany Trump". USA Today. Retrieved July 10, 2022.

- ^ Brown, Tina (January 27, 2005). "Donald Trump, Settling Down". The Washington Post. Retrieved May 7, 2017.

- ^ "Donald Trump Fast Facts". CNN. July 2, 2021. Retrieved September 29, 2021.

- ^ Gunter, Joel (March 2, 2018). "What is the Einstein visa? And how did Melania Trump get one?". BBC News. Retrieved August 2, 2019.

- ^ a b c Barron, James (September 5, 2016). "Overlooked Influences on Donald Trump: A Famous Minister and His Church". The New York Times. Retrieved October 13, 2016.

- ^ a b Scott, Eugene (August 28, 2015). "Church says Donald Trump is not an 'active member'". CNN. Retrieved September 14, 2022.

- ^ a b Schwartzman, Paul (January 21, 2016). "How Trump got religion – and why his legendary minister's son now rejects him". The Washington Post. Retrieved March 18, 2017.

- ^ Kranish & Fisher 2017, p. 81.

- ^ Peters, Jeremy W.; Haberman, Maggie (October 31, 2019). "Paula White, Trump's Personal Pastor, Joins the White House". The New York Times. Retrieved September 29, 2021.

- ^ Jenkins, Jack; Mwaura, Maina (October 23, 2020). "Exclusive: Trump, confirmed a Presbyterian, now identifies as 'non-denominational Christian'". Religion News Service. Archived from the original on October 24, 2020. Retrieved September 29, 2021.

- ^ "Donald Trump says he gets most of his exercise from golf, then uses cart at Turnberry". Golf News Net. July 14, 2018. Retrieved July 4, 2019.

- ^ Rettner, Rachael (May 14, 2017). "Trump thinks that exercising too much uses up the body's 'finite' energy". The Washington Post. Retrieved September 29, 2021.

- ^ a b Marquardt, Alex; Crook, Lawrence III (May 1, 2018). "Exclusive: Bornstein claims Trump dictated the glowing health letter". CNN. Retrieved May 20, 2018.

- ^ Schecter, Anna (May 1, 2018). "Trump doctor Harold Bornstein says bodyguard, lawyer 'raided' his office, took medical files". NBC News. Retrieved June 6, 2019.

- ^ a b c d 1634–1699: 1700–1799: 1800–현재:

- ^ O'Brien, Timothy L. (October 23, 2005). "What's He Really Worth?". The New York Times. Retrieved February 25, 2016.

- ^ a b Diamond, Jeremy; Frates, Chris (July 22, 2015). "Donald Trump's 92-page financial disclosure released". CNN. Retrieved September 14, 2022.

- ^ Walsh, John (October 3, 2018). "Trump has fallen 138 spots on Forbes' wealthiest-Americans list, his net worth down over $1 billion, since he announced his presidential bid in 2015". Business Insider. Retrieved October 12, 2021.

- ^ "Profile Donald Trump". Forbes. 2023. Retrieved March 28, 2024.

- ^ Greenberg, Jonathan (April 20, 2018). "Trump lied to me about his wealth to get onto the Forbes 400. Here are the tapes". The Washington Post. Retrieved September 29, 2021.

- ^ Stump, Scott (October 26, 2015). "Donald Trump: My dad gave me 'a small loan' of $1 million to get started". CNBC. Retrieved November 13, 2016.

- ^ Barstow, David; Craig, Susanne; Buettner, Russ (October 2, 2018). "11 Takeaways From The Times's Investigation into Trump's Wealth". The New York Times. Retrieved October 3, 2018.

- ^ a b c d Barstow, David; Craig, Susanne; Buettner, Russ (October 2, 2018). "Trump Engaged in Suspect Tax Schemes as He Reaped Riches From His Father". The New York Times. Retrieved October 2, 2018.

- ^ "From the Tower to the White House". The Economist. February 20, 2016. Retrieved February 29, 2016.

Mr Trump's performance has been mediocre compared with the stockmarket and property in New York.

- ^ Swanson, Ana (February 29, 2016). "The myth and the reality of Donald Trump's business empire". The Washington Post. Retrieved September 29, 2021.

- ^ Alexander, Dan; Peterson-Whithorn, Chase (October 2, 2018). "How Trump Is Trying—And Failing—To Get Rich Off His Presidency". Forbes. Retrieved September 29, 2021.

- ^ a b c Buettner, Russ; Craig, Susanne (May 7, 2019). "Decade in the Red: Trump Tax Figures Show Over $1 Billion in Business Losses". The New York Times. Retrieved May 8, 2019.

- ^ Friedersdorf, Conor (May 8, 2019). "The Secret That Was Hiding in Trump's Taxes". The Atlantic. Retrieved May 8, 2019.

- ^ Buettner, Russ; Craig, Susanne; McIntire, Mike (September 27, 2020). "Long-concealed Records Show Trump's Chronic Losses And Years Of Tax Avoidance". The New York Times. Retrieved September 28, 2020.

- ^ Alexander, Dan (October 7, 2021). "Trump's Debt Now Totals An Estimated $1.3 Billion". Forbes. Retrieved December 21, 2023.

- ^ Alexander, Dan (October 16, 2020). "Donald Trump Has at Least $1 Billion in Debt, More Than Twice The Amount He Suggested". Forbes. Retrieved October 17, 2020.

- ^ a b Mahler, Jonathan; Eder, Steve (August 27, 2016). "'No Vacancies' for Blacks: How Donald Trump Got His Start, and Was First Accused of Bias". The New York Times. Retrieved January 13, 2018.

- ^ a b Rich, Frank (April 30, 2018). "The Original Donald Trump". New York. Retrieved May 8, 2018.

- ^ 블레어 2015, p. 250.

- ^ Qiu, Linda (June 21, 2016). "Yep, Donald Trump's companies have declared bankruptcy...more than four times". PolitiFact. Retrieved May 25, 2023.

- ^ Nevius, James (April 3, 2019). "The winding history of Donald Trump's first major Manhattan real estate project". Curbed.

- ^ Kessler, Glenn (March 3, 2016). "Trump's false claim he built his empire with a 'small loan' from his father". The Washington Post. Retrieved September 29, 2021.

- ^ Kranish & Fisher 2017, p. 84.

- ^ Geist, William E. (April 8, 1984). "The Expanding Empire of Donald Trump". The New York Times. Retrieved September 29, 2021.

- ^ Jacobs, Shayna; Fahrenthold, David A.; O'Connell, Jonathan; Dawsey, Josh (September 3, 2021). "Trump Tower's key tenants have fallen behind on rent and moved out. But Trump has one reliable customer: His own PAC". The Washington Post. Retrieved February 15, 2022.

- ^ a b c Haberman, Maggie (October 31, 2019). "Trump, Lifelong New Yorker, Declares Himself a Resident of Florida". The New York Times. Retrieved January 24, 2020.

- ^ "Trump Revises Plaza Loan". New York Times. November 4, 1992. Retrieved May 23, 2023.

- ^ "Trump's Plaza Hotel Bankruptcy Plan Approved". The New York Times. Reuters. December 12, 1992. Retrieved May 24, 2023.

- ^ Stout, David; Gilpin, Kenneth N. (April 12, 1995). "Trump Is Selling Plaza Hotel To Saudi and Asian Investors". The New York Times. Retrieved July 18, 2019.

- ^ a b Segal, David (January 16, 2016). "What Donald Trump's Plaza Deal Reveals About His White House Bid". The New York Times. Retrieved May 3, 2022.

- ^ Kranish & Fisher 2017, 페이지 298.

- ^ Bagli, Charles V. (June 1, 2005). "Trump Group Selling West Side Parcel for $1.8 billion". The New York Times. Retrieved May 17, 2016.

- ^ a b c McQuade, Dan (August 16, 2015). "The Truth About the Rise and Fall of Donald Trump's Atlantic City Empire". Philadelphia. Retrieved March 21, 2016.

- ^ Kranish & Fisher 2017, p. 128.

- ^ Saxon, Wolfgang (April 28, 1986). "Trump Buys Hilton's Hotel in Atlantic City". The New York Times. Retrieved May 25, 2023.

- ^ Kranish & Fisher 2017, p. 137.

- ^ "Trump's Castle and Plaza file for bankruptcy". UPI. March 9, 1992. Retrieved May 25, 2023.

- ^ Glynn, Lenny (April 8, 1990). "Trump's Taj – Open at Last, With a Scary Appetite". The New York Times. Retrieved August 14, 2016.

- ^ Kranish & Fisher 2017, p. 135.

- ^ "Company News; Taj Mahal is out of Bankruptcy". The New York Times. October 5, 1991. Retrieved May 22, 2008.

- ^ O'Connor, Claire (May 29, 2011). "Fourth Time's A Charm: How Donald Trump Made Bankruptcy Work For Him". Forbes. Retrieved January 27, 2022.

- ^ Norris, Floyd (June 7, 1995). "Trump Plaza casino stock trades today on Big Board". The New York Times. Retrieved December 14, 2014.

- ^ Tully, Shawn (March 10, 2016). "How Donald Trump Made Millions Off His Biggest Business Failure". Fortune. Retrieved May 6, 2018.

- ^ Peterson-Withorn, Chase (April 23, 2018). "Donald Trump Has Gained More Than $100 Million On Mar-a-Lago". Forbes. Retrieved July 4, 2018.

- ^ Dangremond, Sam; Kim, Leena (December 22, 2017). "A History of Mar-a-Lago, Donald Trump's American Castle". Town & Country. Retrieved July 3, 2018.

- ^ Durkee, Allison (May 7, 2021). "Trump Can Legally Live At Mar-A-Lago, Palm Beach Says". Forbes. Retrieved March 7, 2024.

- ^ a b Garcia, Ahiza (December 29, 2016). "Trump's 17 golf courses teed up: Everything you need to know". CNN Money. Retrieved January 21, 2018.

- ^ "Take a look at the golf courses owned by Donald Trump". Golfweek. July 24, 2020. Retrieved July 7, 2021.

- ^ a b Anthony, Zane; Sanders, Kathryn; Fahrenthold, David A. (April 13, 2018). "Whatever happened to Trump neckties? They're over. So is most of Trump's merchandising empire". The Washington Post. Retrieved September 29, 2021.

- ^ Martin, Jonathan (June 29, 2016). "Trump Institute Offered Get-Rich Schemes With Plagiarized Lessons". The New York Times. Retrieved January 8, 2021.

- ^ Williams, Aaron; Narayanswamy, Anu (January 25, 2017). "How Trump has made millions by selling his name". The Washington Post. Retrieved December 12, 2017.

- ^ Markazi, Arash (July 14, 2015). "5 things to know about Donald Trump's foray into doomed USFL". ESPN. Retrieved September 30, 2021.

- ^ Morris, David Z. (September 24, 2017). "Donald Trump Fought the NFL Once Before. He Got Crushed". Fortune. Retrieved June 22, 2018.

- ^ O'Donnell & Rutherford 1991, p. 137–143.

- ^ Hogan, Kevin (April 10, 2016). "The Strange Tale of Donald Trump's 1989 Biking Extravaganza". Politico. Retrieved April 12, 2016.

- ^ Mattingly, Phil; Jorgensen, Sarah (August 23, 2016). "The Gordon Gekko era: Donald Trump's lucrative and controversial time as an activist investor". CNN. Retrieved September 14, 2022.

- ^ Peterson, Barbara (April 13, 2017). "The Crash of Trump Air". Daily Beast. Retrieved May 17, 2023.

- ^ "10 Donald Trump Business Failures". Time. October 11, 2016. Retrieved May 17, 2023.

- ^ Blair, Gwenda (October 7, 2018). "Did the Trump Family Historian Drop a Dime to the New York Times?". Politico. Retrieved August 14, 2020.

- ^ Koblin, John (September 14, 2015). "Trump Sells Miss Universe Organization to WME-IMG Talent Agency". The New York Times. Retrieved January 9, 2016.

- ^ Nededog, Jethro (September 14, 2015). "Donald Trump just sold off the entire Miss Universe Organization after buying it 3 days ago". Business Insider. Retrieved May 6, 2016.

- ^ Rutenberg, Jim (June 22, 2002). "Three Beauty Pageants Leaving CBS for NBC". The New York Times. Retrieved August 14, 2016.

- ^ de Moraes, Lisa (June 22, 2002). "There She Goes: Pageants Move to NBC". The Washington Post. Retrieved August 14, 2016.

- ^ Zara, Christopher (October 26, 2016). "Why the heck does Donald Trump have a Walk of Fame star, anyway? It's not the reason you think". Fast Company. Retrieved June 16, 2018.

- ^ Puente, Maria (June 29, 2015). "NBC to Donald Trump: You're fired". USA Today. Retrieved July 28, 2015.

- ^ Cohan, William D. (December 3, 2013). "Big Hair on Campus: Did Donald Trump Defraud Thousands of Real Estate Students?". Vanity Fair. Retrieved March 6, 2016.

- ^ Barbaro, Michael (May 19, 2011). "New York Attorney General Is Investigating Trump's For-Profit School". The New York Times. Retrieved September 30, 2021.

- ^ Lee, Michelle Ye Hee (February 27, 2016). "Donald Trump's misleading claim that he's 'won most of' lawsuits over Trump University". The Washington Post. Retrieved February 27, 2016.

- ^ McCoy, Kevin (August 26, 2013). "Trump faces two-front legal fight over 'university'". USA Today. Retrieved September 29, 2021.

- ^ Barbaro, Michael; Eder, Steve (May 31, 2016). "Former Trump University Workers Call the School a 'Lie' and a 'Scheme' in Testimony". The New York Times. Retrieved March 24, 2018.

- ^ Montanaro, Domenico (June 1, 2016). "Hard Sell: The Potential Political Consequences of the Trump University Documents". NPR. Retrieved June 2, 2016.

- ^ Eder, Steve (November 18, 2016). "Donald Trump Agrees to Pay $25 Million in Trump University Settlement". The New York Times. Retrieved November 18, 2016.

- ^ Tigas, Mike; Wei, Sisi (May 9, 2013). "Nonprofit Explorer". ProPublica. Retrieved September 9, 2016.

- ^ Fahrenthold, David A. (September 1, 2016). "Trump pays IRS a penalty for his foundation violating rules with gift to aid Florida attorney general". The Washington Post. Retrieved September 30, 2021.

- ^ a b Fahrenthold, David A. (September 10, 2016). "How Donald Trump retooled his charity to spend other people's money". The Washington Post. Retrieved March 19, 2024.

- ^ Pallotta, Frank (August 18, 2022). "Investigation into Vince McMahon's hush money payments reportedly turns up Trump charity donations". CNN. Retrieved March 19, 2024.

- ^ Solnik, Claude (September 15, 2016). "Taking a peek at Trump's (foundation) tax returns". Long Island Business News. Retrieved September 30, 2021.

- ^ Cillizza, Chris; Fahrenthold, David A. (September 15, 2016). "Meet the reporter who's giving Donald Trump fits". The Washington Post. Retrieved June 26, 2021.

- ^ Fahrenthold, David A. (October 3, 2016). "Trump Foundation ordered to stop fundraising by N.Y. attorney general's office". The Washington Post. Retrieved May 17, 2023.

- ^ Jacobs, Ben (December 24, 2016). "Donald Trump to dissolve his charitable foundation after mounting complaints". The Guardian. Retrieved December 25, 2016.

- ^ Thomsen, Jacqueline (June 14, 2018). "Five things to know about the lawsuit against the Trump Foundation". The Hill. Retrieved June 15, 2018.

- ^ Goldmacher, Shane (December 18, 2018). "Trump Foundation Will Dissolve, Accused of 'Shocking Pattern of Illegality'". The New York Times. Retrieved May 9, 2019.

- ^ Katersky, Aaron (November 7, 2019). "President Donald Trump ordered to pay $2M to collection of nonprofits as part of civil lawsuit". ABC News. Retrieved November 7, 2019.

- ^ "Judge orders Trump to pay $2m for misusing Trump Foundation funds". BBC News. November 8, 2019. Retrieved March 5, 2020.

- ^ a b Mahler, Jonathan; Flegenheimer, Matt (June 20, 2016). "What Donald Trump Learned From Joseph McCarthy's Right-Hand Man". The New York Times. Retrieved May 26, 2020.

- ^ Kranish, Michael; O'Harrow, Robert Jr. (January 23, 2016). "Inside the government's racial bias case against Donald Trump's company, and how he fought it". The Washington Post. Retrieved January 7, 2021.

- ^ Dunlap, David W. (July 30, 2015). "1973: Meet Donald Trump". The New York Times. Retrieved May 26, 2020.

- ^ Brenner, Marie (June 28, 2017). "How Donald Trump and Roy Cohn's Ruthless Symbiosis Changed America". Vanity Fair. Retrieved May 26, 2020.

- ^ "Donald Trump: Three decades, 4,095 lawsuits". USA Today. Archived from the original on April 17, 2018. Retrieved April 17, 2018.

- ^ a b Winter, Tom (June 24, 2016). "Trump Bankruptcy Math Doesn't Add Up". NBC News. Retrieved February 26, 2020.

- ^ Flitter, Emily (July 17, 2016). "Art of the spin: Trump bankers question his portrayal of financial comeback". Reuters. Retrieved October 14, 2018.