모니터

mTORrapamycin(mTOR)[5]의 포유류의 목표도 정도의 기계적 목표이고, 때때로FK506-binding 단백질12-rapamycin-associated 단백질 1(FRAP1), 효소가 인간의 MTOR 유전자에 의해 박혀 있기로 언급했다.단백질 kinases의 phosphatidylinositol3-kinase-related 인산화 효소 가족의[6][7][8]mTOR 일원이다.[9]

mTOR은 다른 단백질과 연결되고 서로 다른 세포 [10]과정을 조절하는 두 개의 다른 단백질 복합체, mTOR 복합체 1과 mTOR 복합체 2의 핵심 성분으로 작용한다.특히 mTOR은 두 복합체의 핵심성분으로서 세포성장, 세포증식, 세포운동성, 세포생존성, 단백질합성, 자가파지 및 [10][11]전사를 조절하는 세린/트레오닌 단백질인산화효소로서 기능한다.mTORC2의 핵심 성분으로서 mTOR는 인슐린 수용체와 인슐린 유사 성장인자 1 [12]수용체의 활성화를 촉진하는 티로신 단백질 키나제로서도 기능하며, mTORC2는 액틴 세포골격의 [10][13]제어 및 유지에도 관여하고 있다.

검출

라파누이(이스터 섬 - 칠레)

TOR의 연구는 1960년대 이스터 섬(섬 주민들에 의해 라파 누이로 알려져 있음)으로의 탐험에서 시작되었으며, 치료 가능성이 있는 식물과 토양에서 천연물을 식별하는 것을 목표로 한다.1972년 수렌 세갈은 토양 박테리아 Streptomyces hygroscopicus에서 추출한 작은 분자를 확인했는데, 이 분자는 처음에 강력한 항진균 활성을 가지고 있는 것으로 보고되었습니다.그는 원래 소스와 활성에 주목하여 적절한 이름을 라파마이신이라고 지었다(Sehgal et al., 1975).그러나 초기 테스트 결과 라파마이신은 면역억제 및 세포항암 활성도 있는 것으로 밝혀졌다.Rapamycin은 Wyeth-Ayerst가 면역 체계에 대한 Rapamycin의 영향을 더 자세히 조사하려는 Sehgal의 노력을 지지했던 1980년대까지 처음에는 제약 업계로부터 큰 관심을 받지 못했다.이것은 결국 신장 이식에 따른 면역 억제제로 FDA의 승인을 이끌어냈다.하지만, FDA의 승인 이전에, 라파마이신이 어떻게 작용했는지는 완전히 알려지지 않았다.라파마이신의 발견과 초기 연구의 이야기는 팟캐스트 라디오랩의 "더러운 약물과 아이스크림 통" 에피소드에서 전해졌습니다.

후속 이력

TOR과 mTOR의 발견은 조셉 하이트만, 라오 모브바, 마이클 N.[14] 홀의 자연산물 라파마이신, 데이비드 M. 사바티니, 헤디예 Erdjument-Bromage, Mary Lui, Paul Tempst, Solomon Handy의 독립적인 [7]연구에서 비롯되었다.윌리엄스, 프랜시스 듀몬트, 그레고리 위더레흐트, 그리고 로버트 T.[8] 에이브러햄.1993년, 로버트 카퍼키, 조지 리비, 그리고 동료들과 Jeannette Kunz, Michael N. Hall, 그리고 동료들은 TOR/DRR 유전자로 [15][16]알려진 곰팡이에서 라파마이신의 독성을 중재하는 유전자를 독립적으로 복제했다.그러나 포유류에서 FKBP12-라파마이신 복합체의 분자 표적은 알려지지 않았다.1994년, 스튜어트 L. 슈라이버, 솔로몬 H. 스나이더, 그리고 로버트 T. 에이브러햄의 연구실에서 일하는 연구원들은 독립적으로 효모 TOR/[6][7][8]DR 유전자에 대한 호몰로지 때문에 mTOR로 알려지게 된 FKBP12-라파마이신과 직접적으로 상호작용하는 단백질을 발견했다.

라파마이신은 세포 주기의 G1 단계에서 곰팡이 활동을 억제한다.포유동물에서는 [17]T림프구의 G1에서 S로의 상전이를 차단함으로써 면역체계를 억제한다.장기이식 [18]후 면역억제제로 사용된다.라파마이신에 대한 관심은 1987년 구조적으로 관련된 면역억제 천연물 FK506의 발견 이후 다시 나타났다.1989-90년에 FK506과 라파마이신은 각각 [19][20]T세포 수용체(TCR)와 IL-2 수용체 신호 전달 경로를 억제하는 것으로 확인되었다.두 천연물은 FKBP12를 포함한 FK506-및 라파마이신 결합 단백질을 발견하기 위해 사용되었으며, FKBP12–FK506과 FKBP12–라파마이신이 별개의 세포 기능을 대상으로 하는 기능 게인 메커니즘을 통해 작용할 수 있다는 증거를 제공하기 위해 사용되었다.이러한 조사에는 FK506과 라파마이신이 상호 [21][22]길항제 역할을 한다는 것을 보여주는 데 기여하는 Merck의 Francis Dumont와 Nolan Sigal의 주요 연구가 포함되었다.이러한 연구는 FKBP12를 라파마이신의 가능한 표적으로 포함시켰지만 복합체가 기계적 [23][24]캐스케이드의 다른 원소와 상호작용할 수 있음을 시사했다.

1991년 칼시뉴린은 FKBP12-FK506의 [25]표적으로 확인되었다.때까지에서 분자 유전학은 정도의 대상으로 FKBP12 설립된 그 FKBP12-rapamycin의, 그리고 FKBP12-rapamycin의 대상으로 1991년과 1993,[14][26]에서 1994년에 몇몇 단체 독립적으로 공부하는 데에 직접적인 대상으로서mTOR 인산화 효소 발견 연구에 의해 뒤 TOR1과 TOR2 연루된 신비한 남아 있었다. 포유 동물이안 [6][7][18]조직mTOR의 배열 분석 결과 1991년 8월과 1993년 5월 조셉 하이트만, 라오 무바, 마이클 N. 홀이 식별한 라파마이신 1과 2(TOR1과 TOR2) 유전자의 효모 표적에 의해 코드된 단백질의 직접 직교인 것으로 밝혀졌다.독립적으로, George Livi와 동료들은 1993년 10월에 발표된 연구에서 그들이 지배적인 라파마이신 내성 1과 2(DRR1과 DRR2)라고 부르는 같은 유전자를 나중에 보고했다.

현재 mTOR로 불리는 이 단백질은 원래 Stuart L. Schreiber에 의해 FRAP로 명명되었고 David M. [6][7]Sabatini에 의해 RAFT1로 명명되었다. FRAP1은 인간의 공식 유전자 기호로 사용되었다.이러한 다른 이름 때문에 처음으로 로버트 T. Abraham,[6]에 의해 사용되어 졌다 mTOR, 점점 더 과학자들은mTOR 경로에 단백질을 언급할 때 일하는 것의 커뮤니티와 TOR단백질의 열적 과부하 계전기, 대상 Rapamycin 대신에, 조는 Heitman, Rao Movva에 의해서 이름이 지어졌다 이스트에서 원본 발견이란 것에 경의를 표하는에 의해, 마이크 H. 입양되었다알l. TOR은 1991년 스위스 바젤에 있는 Biozentrum and Sandoz Pharmacuticals에서 처음 발견되었으며, TOR은 독일어로 출입구 또는 출입문을 의미하며, 바젤 시는 한때 상징적인 Spalentor를 [27]포함한 시내로 통하는 문으로 둘러싸여 있었기 때문에 TOR이라는 이름이 더욱 존경의 의미를 담고 있습니다."mTOR"는 처음에는 "라파마이신"의 맘마리아 표적을 의미했지만, "m"의 의미는 나중에 "기계적"[28]으로 바뀌었다.마찬가지로, 이후 발견으로 얼룩말 물고기 TOR는 zTOR, 아라비도시스 탈리아나 TOR는 AtTOR, 드로소필라 TOR는 dTOR로 명명되었다.2009년 FRAP1 유전자명은 HUGO Gen Nomenclature Committee(HGNC)에 의해 mTOR로 공식 변경되었으며, 이는 라파마이신의 [29]기계적 표적을 의미한다.

TOR의 발견과 그에 따른 mTOR의 확인은 현재 mTOR 경로라고 불리는 것의 분자 및 생리학적 연구의 문을 열었고, 작은 분자가 생물학의 탐사로 사용되는 화학 생물학 분야의 성장에 촉매적인 영향을 미쳤다.

기능.

mTOR은 인슐린, 성장인자(IGF-1, IGF-2 등) 및 아미노산을 [11]포함한 상류 경로로부터의 입력을 통합합니다.mTOR는 세포의 영양소,[30] 산소 및 에너지 수준도 감지합니다.mTOR 경로는 간, 근육, 백색 및 갈색 지방 조직 [31]및 뇌를 포함한 조직의 기능에서 중요한 역할을 하는 포유류의 신진대사와 생리의 중심 조절 장치이며 당뇨병, 비만, 우울증 및 특정 [32][33]암과 같은 인간 질병에서 조절이 잘 되지 않습니다.라파마이신은 세포내 수용체 FKBP12와 [34][35]관련지어 mTOR를 억제한다.FKBP12-라파마이신 복합체는 mTOR의 FKBP12-라파마이신 결합(FRB) 도메인에 직접 결합하여 [35]활성을 억제한다.

콤플렉스

mTOR은 구조적으로 구별되는 두 가지 복합체, 즉 mTORC1과 mTORC2의 [36]촉매 서브 유닛이다.두 복합체는 서로 다른 세포 하위 구획에 위치하여 활성화와 [37]기능에 영향을 미친다.Rheb에 의해 활성화되면 mTORC1은 리소좀 표면에서 래귤레이터-라그 복합체에 국소화되며, 충분한 아미노산이 [38][39]존재할 때 활성화된다.

mTORC1

mTOR 복합체 1(mTORC1)은 mTOR의 조절 관련 단백질인 mTOR(랩터), SEC13 단백질 8(mLST8)과 비핵심 성분인 PRAS40 및 [40][41]DEPTOR로 구성되어 있다.이 복합체는 영양소/에너지/레독스 센서의 기능을 하며 단백질 [11][40]합성을 제어합니다.mTORC1의 활성은 라파마이신, 인슐린, 성장인자, 포스파티드산, 특정 아미노산 및 이들의 유도체(예: L-류신 및 β-히드록시β-메틸낙산), 기계적 자극 및 산화 [40][42][43]스트레스에 의해 조절된다.

mTORC2

MTOR 제2단지(mTORC2)MTOR, MTOR(RICTOR), MLST8의rapamycin-insensitive도 상대, 포유류의 스트레스 활성화 단백질 인산화 효소 단백질 1(mSIN1)상호 작용으로 구성되어 있다.[44][45]mTORC2는 액틴 cytoskeleton의 F-actin 스트레스 섬유, paxillin, RhoA, Rac1, Cdc42의 자극을 통해 중요한 규제 당국인과 p.을 보여 주고 있다또한 mTORC2는 세린 잔류물 Ser473에서 세린/트레오닌 단백질 키나제 Akt/[45]PKB를 인산화하여 신진대사와 [46]생존에 영향을 미친다.mTORC2에 의한 Akt의 세린잔기 Ser473의 인산화 작용은 PDK1에 의한 트레오닌잔기 Thr308에 대한 Akt 인산화 작용을 자극하여 완전한 Akt [47][48]활성화로 이어진다.또한 mTORC2는 티로신 단백질인산화효소 활성을 나타내며, 티로신 잔류물 Tyr1131/1136 및 Tyr1146/1151에 인슐린 유사성장인자1 수용체(IGF-1R)와 인슐린 수용체(InsR)를 각각 인산화하여 IGF-IR [12]및 InsR의 완전활성화를 도모한다.

라파마이신에 의한 억제

라파마이신은 mTORC1을 억제하며, 이것은 약물의 대부분의 유익한 효과를 제공하는 것으로 보인다(동물 연구에서 수명 연장을 포함한다).라파마이신은 mTORC2에 보다 복잡한 영향을 미치며, 장기 노출 시 특정 세포 유형에서만 억제된다.mTORC2의 교란은 포도당 내성 저하와 [49]인슐린에 대한 무감각이라는 당뇨병과 같은 증상을 일으킨다.

유전자 결실 실험

mTORC2 시그널링 패스는 mTORC1 시그널링 패스에 비해 정의되어 있지 않습니다.mTORC 복합체 구성요소의 기능은 녹다운과 녹아웃을 사용하여 연구되었으며 다음과 같은 표현형을 생성하는 것으로 확인되었다.

- NIP7: mTORC2 [50]기질의 인산화 감소로 나타나는 mTORC2 활성을 감소시켰다.

- RICTOR: 과잉발현은 전이를 초래하고 녹다운은 성장인자에 의해 유도되는 PKC-인산화를 [51]억제한다.생쥐에서 Rictor의 구성 결실은 배아 치사성을 [52]초래하는 반면, 조직 특이 결실은 다양한 표현형을 초래한다. 간, 백색 지방 조직 및 췌장 베타 세포에서 Rictor 결실의 일반적인 표현형은 하나 이상의 [49][53][54][55]조직에서의 전신 포도당 불내증과 인슐린 저항성이다.생쥐에서 Rictor 발현이 감소하면 수컷의 [56]수명은 감소하지만 암컷은 감소하지 않습니다.

- mTOR : PP242에 의한 mTORC1 및 mTORC2의 저해 [2-(4-아미노-1-이소프로필-1H-피라졸로[3,4-d]피리미딘-3-yl)-1H-인돌-5-ol]는 mTOR 단독 억제 또는 아포토시스(apoptosisision)로 이어진다.생쥐의 mTOR 발현 유전자 감소는 [58]수명을 크게 증가시킨다.

- PDK1: 녹아웃은 치명적입니다.하이포메트릭 대립 유전자는 장기 부피와 유기체의 크기가 작아지지만 정상적인 AKT [59]활성화가 됩니다.

- AKT: 녹아웃 마우스는 자연사망증(AKT1), 심각한 당뇨병(AKT2), 작은 뇌(AKT3), 그리고 성장 결핍증(AKT1/AKT2)을 [60]경험합니다.AKT1에 대해 헤테로 접합된 생쥐는 수명을 [61]증가시켰다.

- mTORC1의 S. cerevisiae 정형어인 TOR1은 탄소 대사와 질소 대사의 조절제이며, TOR1 KO 균주는 질소 반응과 탄소 가용성을 조절하여 [62][63]효모의 핵심 영양 변환제임을 나타냅니다.

임상적 의의

에이징

TOR 활성 감소는 S. cerevisiae, C. elegans,[64][65][66][67] D. melanogaster에서 수명을 늘리는 것으로 밝혀졌다.mTOR 억제제 라파마이신은 생쥐의 [68][69][70][71][72]수명을 늘리는 것으로 확인되었다.

칼로리 제한과 메티오닌 제한과 같은 일부 식사 방식은 mTOR [64][65]활성을 감소시킴으로써 수명 연장을 유발한다는 가설이 있다.일부 연구는 적어도 지방 조직과 같은 특정 조직에서 노화 동안 mTOR 시그널링이 증가할 수 있으며, 라파마이신은 부분적으로 이러한 [73]증가를 차단함으로써 작용할 수 있다고 제안했다.대안 이론은 mTOR 시그널링이 길항다원성의 한 예이며, 높은 mTOR 시그널링은 초기 생애에는 좋지만 노년기에는 부적절하게 높은 수준으로 유지된다는 것이다.칼로리 제한과 메티오닌 제한은 부분적으로 [74]mTOR의 강력한 활성제인 류신 및 메티오닌을 포함한 필수 아미노산의 수준을 제한함으로써 작용할 수 있다.쥐의 뇌에 류신을 투여하면 [75]시상하부에 있는 mTOR 경로의 활성화를 통해 음식 섭취와 체중을 감소시키는 것으로 나타났다.

노화의 [76]유리기가론에 따르면 활성산소종은 미토콘드리아 단백질에 손상을 입히고 ATP 생산을 감소시킨다.이어서 mTORC1이 리보솜을 [17]활성화하는 인산화 캐스케이드를 개시하기 때문에 ATP 감수성 AMPK를 통해 mTOR 경로가 억제되고 ATP 소비성 단백질 합성이 하향 조절된다.따라서 손상된 단백질의 비율이 향상된다.또한 mTORC1의 교란은 미토콘드리아 [77]호흡을 직접적으로 억제한다.에이징 프로세스에 대한 다음과 같은 긍정적인 피드백은 보호 메커니즘에 의해 상쇄됩니다.감소된 mTOR 활성은 (다른 요인 중에서도) 자동 [76]파지를 통한 기능 장애가 있는 세포 구성요소의 제거를 상향 조절한다.

mTOR은 노화 관련 분비 표현형(SASP)[78]의 주요 개시제이다.Interleukin 1 alpha(IL1A)[79][80]는 NF-δB와의 양성 피드백 루프에 의해 SASP 인자의 생성에 기여하는 노화전지의 표면에서 발견된다.IL1A에 대한 mRNA의 번역은 mTOR [81]활성에 크게 의존합니다.[79] mTOR 활성은 MAPKAPK2에 의해 매개되는 IL1A의 수준을 증가시킵니다. ZFP36L1의 mTOR 억제는 이 단백질이 SASP [82]인자의 수많은 성분의 전사물을 분해하는 것을 방지합니다.

암

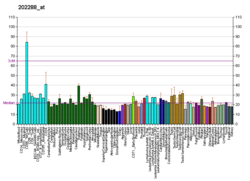

mTOR 시그널링의 과잉 활성화는 종양의 시작과 발달에 유의하게 기여하고 mTOR 활성은 유방, 전립선, 폐, 흑색종, 방광, 뇌 [83]및 신장암을 포함한 많은 유형의 암에서 규제 해제되는 것으로 확인되었다.체질이 활성화되는 이유는 여러 가지가 있다.가장 흔한 것은 종양 억제제 PTEN 유전자의 돌연변이이다.PTEN 포스파타아제는 mTOR의 업스트림 이펙터인 PI3K의 영향을 방해하여 mTOR 시그널링에 부정적인 영향을 미친다.또한, 많은 암에서 PI3K [84]또는 Akt의 활성 증가로 mTOR 활성은 규제 해제된다.마찬가지로 다운스트림 mTOR 효과인자 4E-BP1, S6K 및 eIF4E의 과잉 발현은 암 [85]예후 불량으로 이어진다.또한 mTOR의 활성을 저해하는 TSC 단백질의 돌연변이는 양성 병변으로 나타나 신장세포암 [86]위험을 높이는 결핵성 경화 복합체라는 상태를 초래할 수 있다.

mTOR 활성 증가는 주로 단백질 합성에 미치는 영향 때문에 세포 주기 진행을 촉진하고 세포 증식을 증가시키는 것으로 나타났다.또한 활성 mTOR은 자가파지를 [87]억제함으로써 종양 성장을 간접적으로 지원한다.체질활성 mTOR은 HIF1A의 번역을 증가시키고 혈관신생을 [88]지원함으로써 암세포에 산소와 영양분을 공급하는 기능을 하며, 또한 암세포의 성장률 증가를 지원하는 또 다른 대사적응을 돕는다.mTOR, 특히 mTORC2의 기질인 Akt2는 당분해효소 PKM2의 발현을 상향 조절하여 바르부르크 [89]효과에 기여한다.

중추신경계 장애/뇌기능

이 섹션은 다음과 같이 확장이 필요합니다. 추가가 가능합니다. (2016년 10월) |

자폐증

mTOR은 자폐 스펙트럼 [90]장애에서 흥분성 시냅스의 '프루닝' 메커니즘의 실패와 관련이 있다.

알츠하이머병

mTOR 시그널링은 알츠하이머병(AD) 병리와 여러 측면에서 교차하여 질병 진행에 기여하는 잠재적 역할을 시사한다.일반적으로 연구결과는 AD 뇌에서 mTOR 시그널링 과잉활성을 보여준다.예를 들어, 인간 AD 뇌에 대한 사후 연구는 PTEN, Akt, S6K 및 [91][92][93]mTOR의 조절 장애를 드러낸다. mTOR 시그널링은 각각 [94]질병의 두 가지 특징인 Aβ 플라크와 신경섬유 엉킴을 형성하고 있는 가용성 아밀로이드 베타(Aβ)와 타우 단백질의 존재와 밀접한 관련이 있는 것으로 보인다.시험관내 연구에서 Aβ는 PI3K/AKT 경로의 활성제이며, 이는 다시 mTOR를 [95]활성화하는 것으로 나타났다.또한 Aβ를 N2K 세포에 적용하면 결국 신경섬유 [96][97]엉킴이 발달하는 뉴런에서 높은 발현을 보이는 것으로 알려진 mTOR의 하류 표적인 p70S6K의 발현을 증가시킨다.7PA2 가족 AD 돌연변이에 감염된 중국산 햄스터 난소 세포도 대조군에 비해 mTOR 활성이 증가하며 감마시크리테아제 [98][99]억제제를 사용하여 과잉활성을 차단한다.이러한 체외 연구는 Aβ 농도가 증가하면 mTOR 시그널링이 증가하지만, 세포독성 Aβ 농도가 유의미하게 증가하면 mTOR [100]시그널링이 감소하는 것으로 생각된다.

체외에서 관찰된 데이터와 일관되게 mTOR 활성과 활성화된 p70S6K는 [99][101]대조군에 비해 AD 동물 모델의 피질 및 해마에서 유의미하게 증가하는 것으로 나타났다.AD의 동물 모델에서 Aβ의 약리학적 또는 유전적 제거는 [101]mTOR 시그널링에서 Aβ의 직접적인 관여를 지적하면서 정상적인 mTOR 활성의 중단을 제거한다.또한 정상적인 생쥐의 해마에 Aβ 올리고머를 주입함으로써 mTOR 과잉활성을 [101]관찰할 수 있다.AD의 특징적인 인지 장애는 PRAS-40의 인산화로 매개되는 것으로 보이며, PRAS-40 인산화 억제는 Aβ 유도 mTOR [101][102][103]과활성을 방지한다.이러한 발견을 고려할 때 mTOR 신호 경로는 AD에서 Aβ 유도 독성의 한 메커니즘으로 보인다.

p70S6K 활성화는 인산화 증가와 탈인산화 [96][104][105][106]감소를 통해 엉킴 형성과 mTOR 과잉 활성을 촉진하는 것으로 나타났다.또한 mTOR이 타우와 다른 [107]단백질의 변환을 증가시킴으로써 타우 병리학에 기여한다는 것이 제안되었다.

시냅스 가소성은 학습과 기억력에 중요한 역할을 합니다. 이 두 가지 과정은 AD 환자에게서 심각하게 손상됩니다.번역 제어 또는 단백질 항상성 유지는 신경 가소성에 필수적이며 [99][108][109][110][111]mTOR에 의해 조절되는 것으로 나타났습니다.mTOR 활동을 통한 단백질 과잉과 저생산 모두 학습과 기억력 저하에 기여하는 것으로 보인다.또한 mTOR 과잉활동으로 인한 결손이 라파마이신에 의한 치료를 통해 완화될 수 있다는 점에서 mTOR은 시냅스 [95][112]가소성을 통해 인지기능에 영향을 미치는 데 중요한 역할을 할 수 있다.신경변성에서의 mTOR 활성에 대한 추가 증거는 mTOR 경로의 상류 표적인 eIF2α-P가 지속적인 번역 [113]억제를 통해 프리온 질환의 세포사를 매개한다는 것을 보여주는 최근의 연구 결과로부터 나온다.

일부 증거는 또한 감소된 Aβ 클리어런스에서 mTOR의 역할을 지적한다. mTOR는 자동 [114]파지의 음성 조절기이다. 따라서 mTOR 시그널링의 과잉 활동은 AD 뇌에서 Aβ 클리어런스를 감소시켜야 한다.자동 파지의 교란은 [115][116][117][118][119][120]AD를 포함한 단백질 오접힘 질환의 잠재적 병원성 원인일 수 있다.헌팅턴병의 마우스 모델을 사용한 연구는 라파마이신을 통한 치료가 헌팅틴 [121][122]골재 제거를 용이하게 한다는 것을 보여준다.아마도 같은 처리는 Aβ 퇴적물을 제거하는 데도 유용할 수 있다.

림프 증식성 질환

과활성 mTOR 경로는 자가면역 림프증식증후군(ALPS),[123] 다실성 캐슬맨병 [124]및 이식 후 림프증식장애(PTLD)[125]와 같은 특정 림프증식성 질환에서 확인되었다.

단백질 합성 및 세포 성장

mTORC1 활성화는 신체적인 운동과 특정 아미노산 또는 아미노산 [126][127]유도체의 섭취에 대한 반응으로 인간의 근섬유근 단백질 합성과 골격근 비대증에 필요하다.골격근의 mTORC1 시그널링의 지속적인 불활성화는 노년기의 근육 소모, 암의 캐시샤, 물리적 [126][127][128]비활성화에 의한 근육 위축을 촉진한다.mTORC2 활성화는 분화된 마우스 신경2a [129]세포의 신경계 발육을 매개하는 것으로 보인다.β-히드록시β-메틸부틸레이트에 의한 전전두신경세포의 간헐적 mTOR 활성화는 동물에서 수지상 가지치기(dendrite pruning)와 관련된 노화 관련 인지 저하를 억제하며,[130] 이는 인간에서도 관찰되는 현상이다.

• PA: 포스파티드산

• mTOR: 라파마이신의 기계적 표적

• AMP: 아데노신 일인산

• ATP: 아데노신3인산

• AMPK: AMP활성화단백질인산화효소

• PGC11α: 페르옥시좀 증식제 활성화 수용체 감마 공동활성화제-1α

• S6K1: p70S6인산화효소

• 4EBP1: 진핵생물 번역 개시인자 4E결합단백질 1

• eIF4E: 진핵생물 번역 개시인자 4E

• RPS6: 리보솜 단백질 S6

• eEF2: 진핵생물 신장인자 2

• RE: 저항 운동, EE: 지구력 운동

• 미오: 근섬유; 미토: 미토콘드리아

• AA: 아미노산

• HMB : β-히드록시β-메틸낙산

• ↑는 활성화를 나타냅니다.

• δ는 억제를 나타낸다.

리소좀 손상은 mTOR을 억제하고 자가파지를 유도한다.

능동 mTORC1 lysosomes에. mTOR은 inhibited[132] 때 리소 좀 막 침입하는 박테리아 등 다양한 또는 내인 외인성 요원membrane-permeant 화학 물질 삼투하여 적극적인 제품(부상의 이 형식은 lysosomes에 polymerize membrane-permeant dipeptide들을 사용하여 모델링 할 수 있), 상냥한 사람의 국부 항복에 의해 손상된 배치한다.얇은 셀룰로이드 조각단백질 응집체(위 알츠하이머병 섹션 참조) 및 요산염 결정 및 결정 [132]실리카를 포함한 세포질 유기 또는 무기 함유물.리소좀/엔도엠브레인 이후의 mTOR 불활성화 과정은 [132]GALTOR라는 단백질 복합체에 의해 매개된다.GALTOR의[132] 중심에는 세포질 렉틴의 β-갈락토시드 결합 슈퍼패밀리의 일원인 갈렉틴-8이 있으며, 갈렉틴은 구분하는 내막브란의 내막측 노출 글리칸에 결합함으로써 리소좀막 손상을 인식한다.막 손상 후, 항상성 조건에서 일반적으로 mTOR과 관련된 갈렉틴-8은 더 이상 mTOR과 상호작용하지 않고 대신 SLC38A9, RRAGA/RAGB 및 LAMTOR1에 결합하여 라그레이터(LAMTOR1-5 복합체) 구아닌 뉴클레오티드 교환 기능을[132] 억제한다.

TOR은 일반적으로 자동 파지의 음성 조절기이며,[133][134][135][136][137] 대사 반응인 기아에 대한 반응 중에 가장 잘 연구된다.그러나 리소좀 손상 동안 mTOR 억제는 품질 관리 기능에서 자가포지 반응을 활성화하여 손상된 리소좀을 제거하는 리소파지라고[138] 불리는 과정을 이끈다.이 단계에서 또 다른 갈렉틴인 갈렉틴-3은 TRIM16과 상호작용하여 손상된 리소좀의 [139][140]선택적 자가파지를 유도한다.TRIM16에는 다른 단지의 ULK1과 주추 요소(Beclin 1과 ATG16L1)(Beclin 1-VPS34-ATG14과 ATG16L1-ATG5-ATG12)시작 그들의 많은 직접 ULK1-ATG13 complex,[135][136][137] 같은 혹은 간접적으로 3급 PI3K(Beclin 1, ATG14과 VPS34)의 구성 요소는 mTOR의 음성 제어 중 autophagy,[140]. 이후 그들은 o 의존한다n mTOR에 의해 억제되지 않을 때 ULK1에 의한 인산화 활성화.이러한 자동 파지 구동 컴포넌트는 물리적으로 기능적으로 서로 연결되어 자동 파고좀 형성에 필요한 모든 프로세스를 통합합니다. (i) ULK1-ATG13-FIP200/RB1FIP200/[141][142][143]RB1CC1과 ATG16L1, (ii) ULK1-ATG13-FIP200/RB1 사이의 직접 상호작용을 통해 LC3B/GABARAP 결합기계와 관련된 CC1 복합체CC1 복합체는 ATG13의 HORMA 도메인과 ATG14 [144]사이의 직접적인 상호작용을 통해 Beclin 1-VPS34-ATG14와 관련되며, (iii) ATG16L1은 등급 III PI3K-Beclin 1의 효소 생성물인 PI3P에 결합하는 WIPI2와 상호작용한다.AMPK[132]의 직접 및 활성화는 autophagy 시스템의 주요 부속품들(ULK1,[146]Beclin 1[147])위에 열거하고 추가 inactivates mTORC1,[148][149phosphorylatesgalectin-9(또한 리소 좀 막 위반 인정)를 통해 그러므로mTOR 불활성화, GALTOR[132]을 통해 리소 좀 손상에 시작되고, 게다가 동시 활성화.해결을 강한 autophagy를 허용손상된 리소좀의 유도 및 자가마법 제거.

또한 다음과 같은 여러 유형의 유비쿼티네이션 이벤트가 병렬로 발생하며 갈렉틴 주도 프로세스를 보완합니다.TRIM16-ULK1-Beclin-1의 유비퀴티네이션은 [140]위와 같이 복합체를 안정화시켜 오토파지 활성화를 촉진한다.ATG16L1.ubiquitin[143]에 필요한 내적 결합 관련성을 가지고 있LAMP1, LAMP2, GNS/N-acetylglucosamine-6-sulfatase, TSPAN6/tetraspanin-6, PSAP/prosaposin, TMEM192/transmembrane 단백질 192경우 1 같은 몇가지damage-exposed glycosylated 리소 좀 막 단백질glycoprotein-specificFBXO27-endowed 유비퀴틴 리가 아제에 의해 반면 ubiquitination.50해결 수 있cp62/SQ와 같은 자가파지 수용체를 통한 리소파지 실행에 기여하는리소파지 [143]중에 모집되는 STM1 또는 기타 정해진 기능.

강피증

Scleroderma, 또한 전신성 경화증이라고 알려져 있는 만성적 전신의 자기 면역 질환이 더 많은 심각한 형태의 내부 장기에 영향을 미치는 피부(더마)의(sclero)경화에 의해 특성화된.[151][152]mTOR고,mTORC 경로의 봉쇄 조사를 받고 피부 경화증에 대한 치료제로는 섬유증 의. 질병과 자기 면역에서 역할을 한다.[9]

치료제로서의 mTOR 억제제

이식

mTOR 억제제(예: 라파마이신)는 이식 거부반응을 막기 위해 이미 사용되고 있다.

글리코겐 저장병

일부 기사들은 라파마이신이 골격근에서 GS(글리코겐 합성효소)의 인산화를 증가시킬 수 있도록 mTORC1을 억제할 수 있다고 보고했다.이 발견은 근육에 글리코겐 축적을 수반하는 글리코겐 저장 질환에 대한 잠재적인 새로운 치료적 접근을 나타낸다.

항암제

인간 암 치료에 사용되는 두 가지 주요 mTOR 억제제인 템시롤리무스와 에버리무스가 있다. mTOR 억제제는 신세포암(템시롤리무스)과 췌장암, 유방암, 신세포암(에버올리무스)[153]을 포함한 다양한 악성종양 치료에 사용된다.이들 약물의 전체 메커니즘은 명확하지 않지만 종양 혈관신생을 저해하고 G1/S [154]전이 장애를 야기함으로써 기능하는 것으로 생각된다.

안티에이징

mTOR 억제제는 알츠하이머병 및 파킨슨병과 [156]같은 신경변성질환을 포함한 몇 가지 노화관련 [155]질환의 치료/예방에 유용할 수 있다.노인(65세 이상)에서 mTOR 억제제인 닥톨리시브와 에버리머스를 사용한 단기 치료 후 치료 대상자는 1년 [157]동안 감염 횟수가 감소했다.

에피갈로카테킨 갈레이트(EGCG), 카페인, 커큐민, 베르베린, 케르세틴, 레스베라트롤 및 프테로틸벤을 포함한 다양한 천연 화합물은 [158][159][160]배양 중인 분리 세포에 적용되었을 때 mTOR을 억제하는 것으로 보고되었다.초파리나 생쥐와 같은 동물에게 좋은 결과를 가져왔음에도 불구하고 이러한 물질들이 mTOR 신호를 억제하거나 식이요법 보충제로 복용했을 때 수명을 연장한다는 고품질 증거는 아직 없다.다양한 시험들이 [161][162]진행 중이다.

상호 작용

라파마이신의 기계적 표적은 [163]다음과 상호작용하는 것으로 나타났다.

- ABL1,[164]

- AKT1,[47][165][166]

- IGF-IR,[12]

- InsR,[12]

- CLIP1,[167]

- EIF3F[168]

- EIF4EBP1,[40][169][170][171][172][173][174][175]

- FKBP1A,[13][45][176][177][178][179]

- GPHN,[180]

- KIAA1303,[13][40][44][45][77][169][170][171][181][182][183][184][185][186][187][188][189][190][191][192]

- PRKCD,[193]

- RHEB,[172][194][195][196]

- RICTOR,[13][44][45][183][189][191][192]

- RPS6KB1,[40][170][172][173][174][188][191][197][198][199][200][201][202][203][204]

- STAT1,[205]

- STAT3,[206][207]

- 2포트 채널: TPCN1, TPCN2,[208] 및

- UBQLN1.[209]

레퍼런스

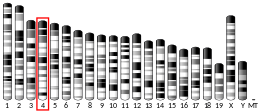

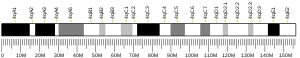

- ^ a b c GRCh38: 앙상블 릴리즈 89: ENSG00000198793 - 앙상블, 2017년 5월

- ^ a b c GRCm38: 앙상블 릴리즈 89: ENSMUSG000028991 - 앙상블, 2017년 5월

- ^ "Human PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ "Mouse PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ Sabers CJ, Martin MM, Brunn GJ, Williams JM, Dumont FJ, Wiederrecht G, Abraham RT (Jan 1995). "Isolation of a Protein Target of the FKBP12-Rapamycin Complex in Mammalian Cells". J. Biol. Chem. 270 (2): 815–22. doi:10.1074/jbc.270.2.815. PMID 7822316.

- ^ a b c d e Brown EJ, Albers MW, Shin TB, Ichikawa K, Keith CT, Lane WS, Schreiber SL (June 1994). "A mammalian protein targeted by G1-arresting rapamycin-receptor complex". Nature. 369 (6483): 756–8. Bibcode:1994Natur.369..756B. doi:10.1038/369756a0. PMID 8008069. S2CID 4359651.

- ^ a b c d e Sabatini DM, Erdjument-Bromage H, Lui M, Tempst P, Snyder SH (July 1994). "RAFT1: a mammalian protein that binds to FKBP12 in a rapamycin-dependent fashion and is homologous to yeast TORs". Cell. 78 (1): 35–43. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(94)90570-3. PMID 7518356. S2CID 33647539.

- ^ a b c Sabers CJ, Martin MM, Brunn GJ, Williams JM, Dumont FJ, Wiederrecht G, Abraham RT (January 1995). "Isolation of a protein target of the FKBP12-rapamycin complex in mammalian cells". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 270 (2): 815–22. doi:10.1074/jbc.270.2.815. PMID 7822316.

- ^ a b Mitra A, Luna JI, Marusina AI, Merleev A, Kundu-Raychaudhuri S, Fiorentino D, Raychaudhuri SP, Maverakis E (November 2015). "Dual mTOR Inhibition Is Required to Prevent TGF-β-Mediated Fibrosis: Implications for Scleroderma". The Journal of Investigative Dermatology. 135 (11): 2873–6. doi:10.1038/jid.2015.252. PMC 4640976. PMID 26134944.

- ^ a b c d e f Lipton JO, Sahin M (October 2014). "The neurology of mTOR". Neuron. 84 (2): 275–291. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2014.09.034. PMC 4223653. PMID 25374355.

The mTOR signaling pathway acts as a molecular systems integrator to support organismal and cellular interactions with the environment. The mTOR pathway regulates homeostasis by directly influencing protein synthesis, transcription, autophagy, metabolism, and organelle biogenesis and maintenance. It is not surprising then that mTOR signaling is implicated in the entire hierarchy of brain function including the proliferation of neural stem cells, the assembly and maintenance of circuits, experience-dependent plasticity and regulation of complex behaviors like feeding, sleep and circadian rhythms. ...

mTOR function is mediated through two large biochemical complexes defined by their respective protein composition and have been extensively reviewed elsewhere(Dibble and Manning, 2013; Laplante and Sabatini, 2012)(Figure 1B). In brief, common to both mTOR complex 1 (mTORC1) and mTOR complex 2 (mTORC2) are: mTOR itself, mammalian lethal with sec13 protein 8 (mLST8; also known as GβL), and the inhibitory DEP domain containing mTOR-interacting protein (DEPTOR). Specific to mTORC1 is the regulator-associated protein of the mammalian target of rapamycin (Raptor) and proline-rich Akt substrate of 40 kDa (PRAS40)(Kim et al., 2002; Laplante and Sabatini, 2012). Raptor is essential to mTORC1 activity. The mTORC2 complex includes the rapamycin insensitive companion of mTOR (Rictor), mammalian stress activated MAP kinase-interacting protein 1 (mSIN1), and proteins observed with rictor 1 and 2 (PROTOR 1 and 2)(Jacinto et al., 2006; Jacinto et al., 2004; Pearce et al., 2007; Sarbassov et al., 2004)(Figure 1B). Rictor and mSIN1 are both critical to mTORC2 function.

그림 1: mTOR 키나제의 도메인 구조와 mTORC1 및 mTORC2 성분

그림 2: mTOR 시그널링 패스 - ^ a b c Hay N, Sonenberg N (August 2004). "Upstream and downstream of mTOR". Genes & Development. 18 (16): 1926–45. doi:10.1101/gad.1212704. PMID 15314020.

- ^ a b c d Yin Y, Hua H, Li M, Liu S, Kong Q, Shao T, Wang J, Luo Y, Wang Q, Luo T, Jiang Y (January 2016). "mTORC2 promotes type I insulin-like growth factor receptor and insulin receptor activation through the tyrosine kinase activity of mTOR". Cell Research. 26 (1): 46–65. doi:10.1038/cr.2015.133. PMC 4816127. PMID 26584640.

- ^ a b c d Jacinto E, Loewith R, Schmidt A, Lin S, Rüegg MA, Hall A, Hall MN (November 2004). "Mammalian TOR complex 2 controls the actin cytoskeleton and is rapamycin insensitive". Nature Cell Biology. 6 (11): 1122–8. doi:10.1038/ncb1183. PMID 15467718. S2CID 13831153.

- ^ a b Heitman J, Movva NR, Hall MN (August 1991). "Targets for cell cycle arrest by the immunosuppressant rapamycin in yeast". Science. 253 (5022): 905–9. Bibcode:1991Sci...253..905H. doi:10.1126/science.1715094. PMID 1715094. S2CID 9937225.

- ^ Kunz J, Henriquez R, Schneider U, Deuter-Reinhard M, Movva NR, and Hall MN (May 1993). "Target of rapamycin in yeast, TOR2, is an essential phosphatidylinositol kinase homolog required for G1 progression". Cell. 73 (3): 585–596. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(93)90144-F. PMID 8387896. S2CID 42926249.

- ^ Cafferkey R, Young PR, McLaughlin MM, Bergsma DJ, Koltin Y, Sathe GM, Faucette L, Eng WK, Johnson RK, Livi GP (October 1993). "Dominant missense mutations in a novel yeast protein related to mammalian phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and VPS34 abrogate rapamycin cytotoxicity". Mol Cell Biol. 13 (10): 6012–23. doi:10.1128/MCB.13.10.6012. PMC 364661. PMID 8413204.

- ^ a b Magnuson B, Ekim B, Fingar DC (January 2012). "Regulation and function of ribosomal protein S6 kinase (S6K) within mTOR signaling networks". The Biochemical Journal. 441 (1): 1–21. doi:10.1042/BJ20110892. PMID 22168436. S2CID 12932678.

- ^ a b Abraham RT, Wiederrecht GJ (1996). "Immunopharmacology of rapamycin". Annual Review of Immunology. 14: 483–510. doi:10.1146/annurev.immunol.14.1.483. PMID 8717522.

- ^ Bierer BE, Mattila PS, Standaert RF, Herzenberg LA, Burakoff SJ, Crabtree G, Schreiber SL (December 1990). "Two distinct signal transmission pathways in T lymphocytes are inhibited by complexes formed between an immunophilin and either FK506 or rapamycin". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 87 (23): 9231–5. Bibcode:1990PNAS...87.9231B. doi:10.1073/pnas.87.23.9231. PMC 55138. PMID 2123553.

- ^ Bierer BE, Somers PK, Wandless TJ, Burakoff SJ, Schreiber SL (October 1990). "Probing immunosuppressant action with a nonnatural immunophilin ligand". Science. 250 (4980): 556–9. Bibcode:1990Sci...250..556B. doi:10.1126/science.1700475. PMID 1700475. S2CID 11123023.

- ^ Dumont FJ, Melino MR, Staruch MJ, Koprak SL, Fischer PA, Sigal NH (February 1990). "The immunosuppressive macrolides FK-506 and rapamycin act as reciprocal antagonists in murine T cells". J Immunol. 144 (4): 1418–24. PMID 1689353.

- ^ Dumont FJ, Staruch MJ, Koprak SL, Melino MR, Sigal NH (January 1990). "Distinct mechanisms of suppression of murine T cell activation by the related macrolides FK-506 and rapamycin". J Immunol. 144 (1): 251–8. PMID 1688572.

- ^ Harding MW, Galat A, Uehling DE, Schreiber SL (October 1989). "A receptor for the immunosuppressant FK506 is a cis-trans peptidyl-prolyl isomerase". Nature. 341 (6244): 758–60. Bibcode:1989Natur.341..758H. doi:10.1038/341758a0. PMID 2477715. S2CID 4349152.

- ^ Fretz H, Albers MW, Galat A, Standaert RF, Lane WS, Burakoff SJ, Bierer BE, Schreiber SL (February 1991). "Rapamycin and FK506 binding proteins (immunophilins)". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 113 (4): 1409–1411. doi:10.1021/ja00004a051.

- ^ Liu J, Farmer JD, Lane WS, Friedman J, Weissman I, Schreiber SL (August 1991). "Calcineurin is a common target of cyclophilin-cyclosporin A and FKBP-FK506 complexes". Cell. 66 (4): 807–15. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(91)90124-H. PMID 1715244. S2CID 22094672.

- ^ Kunz J, Henriquez R, Schneider U, Deuter-Reinhard M, Movva NR, and Hall MN (May 1993). "Target of rapamycin in yeast, TOR2, is an essential phosphatidylinositol kinase homolog required for G1 progression". Cell. 73 (3): 585–596. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(93)90144-F. PMID 8387896. S2CID 42926249.

- ^ Heitman J (November 2015). "On the discovery of TOR as the target of rapamycin". PLOS Pathogens. 11 (11): e1005245. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1005245. PMC 4634758. PMID 26540102.

- ^ Kennedy BK, Lamming DW (2016). "The Mechanistic Target of Rapamycin: The Grand ConducTOR of Metabolism and Aging". Cell Metabolism. 23 (6): 990–1003. doi:10.1016/j.cmet.2016.05.009. PMC 4910876. PMID 27304501.

- ^ "Symbol report for MTOR". HGNC data for MTOR. HUGO Gene Nomenclature Committee. September 1, 2020. Retrieved 2020-12-17.

- ^ Tokunaga C, Yoshino K, Yonezawa K (January 2004). "mTOR integrates amino acid- and energy-sensing pathways". Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 313 (2): 443–6. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2003.07.019. PMID 14684182.

- ^ Wipperman MF, Montrose DC, Gotto AM, Hajjar DP (2019). "Mammalian Target of Rapamycin: A Metabolic Rheostat for Regulating Adipose Tissue Function and Cardiovascular Health". The American Journal of Pathology. 189 (3): 492–501. doi:10.1016/j.ajpath.2018.11.013. PMC 6412382. PMID 30803496.

- ^ Beevers CS, Li F, Liu L, Huang S (August 2006). "Curcumin inhibits the mammalian target of rapamycin-mediated signaling pathways in cancer cells". International Journal of Cancer. 119 (4): 757–64. doi:10.1002/ijc.21932. PMID 16550606. S2CID 25454463.

- ^ Kennedy BK, Lamming DW (June 2016). "The Mechanistic Target of Rapamycin: The Grand ConducTOR of Metabolism and Aging". Cell Metabolism. 23 (6): 990–1003. doi:10.1016/j.cmet.2016.05.009. PMC 4910876. PMID 27304501.

- ^ Huang S, Houghton PJ (December 2001). "Mechanisms of resistance to rapamycins". Drug Resistance Updates. 4 (6): 378–91. doi:10.1054/drup.2002.0227. PMID 12030785.

- ^ a b Huang S, Bjornsti MA, Houghton PJ (2003). "Rapamycins: mechanism of action and cellular resistance". Cancer Biology & Therapy. 2 (3): 222–32. doi:10.4161/cbt.2.3.360. PMID 12878853.

- ^ Wullschleger S, Loewith R, Hall MN (February 2006). "TOR signaling in growth and metabolism". Cell. 124 (3): 471–84. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2006.01.016. PMID 16469695.

- ^ Betz C, Hall MN (November 2013). "Where is mTOR and what is it doing there?". The Journal of Cell Biology. 203 (4): 563–74. doi:10.1083/jcb.201306041. PMC 3840941. PMID 24385483.

- ^ Groenewoud MJ, Zwartkruis FJ (August 2013). "Rheb and Rags come together at the lysosome to activate mTORC1". Biochemical Society Transactions. 41 (4): 951–5. doi:10.1042/bst20130037. PMID 23863162. S2CID 8237502.

- ^ Efeyan A, Zoncu R, Sabatini DM (September 2012). "Amino acids and mTORC1: from lysosomes to disease". Trends in Molecular Medicine. 18 (9): 524–33. doi:10.1016/j.molmed.2012.05.007. PMC 3432651. PMID 22749019.

- ^ a b c d e f Kim DH, Sarbassov DD, Ali SM, King JE, Latek RR, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Sabatini DM (July 2002). "mTOR interacts with raptor to form a nutrient-sensitive complex that signals to the cell growth machinery". Cell. 110 (2): 163–75. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(02)00808-5. PMID 12150925.

- ^ Kim DH, Sarbassov DD, Ali SM, Latek RR, Guntur KV, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Sabatini DM (April 2003). "GbetaL, a positive regulator of the rapamycin-sensitive pathway required for the nutrient-sensitive interaction between raptor and mTOR". Molecular Cell. 11 (4): 895–904. doi:10.1016/S1097-2765(03)00114-X. PMID 12718876.

- ^ Fang Y, Vilella-Bach M, Bachmann R, Flanigan A, Chen J (November 2001). "Phosphatidic acid-mediated mitogenic activation of mTOR signaling". Science. 294 (5548): 1942–5. Bibcode:2001Sci...294.1942F. doi:10.1126/science.1066015. PMID 11729323. S2CID 44444716.

- ^ Bond P (March 2016). "Regulation of mTORC1 by growth factors, energy status, amino acids and mechanical stimuli at a glance". J. Int. Soc. Sports Nutr. 13: 8. doi:10.1186/s12970-016-0118-y. PMC 4774173. PMID 26937223.

- ^ a b c Frias MA, Thoreen CC, Jaffe JD, Schroder W, Sculley T, Carr SA, Sabatini DM (September 2006). "mSin1 is necessary for Akt/PKB phosphorylation, and its isoforms define three distinct mTORC2s". Current Biology. 16 (18): 1865–70. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2006.08.001. PMID 16919458.

- ^ a b c d e Sarbassov DD, Ali SM, Kim DH, Guertin DA, Latek RR, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Sabatini DM (July 2004). "Rictor, a novel binding partner of mTOR, defines a rapamycin-insensitive and raptor-independent pathway that regulates the cytoskeleton". Current Biology. 14 (14): 1296–302. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2004.06.054. PMID 15268862.

- ^ Betz C, Stracka D, Prescianotto-Baschong C, Frieden M, Demaurex N, Hall MN (July 2013). "Feature Article: mTOR complex 2-Akt signaling at mitochondria-associated endoplasmic reticulum membranes (MAM) regulates mitochondrial physiology". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 110 (31): 12526–34. doi:10.1073/pnas.1302455110. PMC 3732980. PMID 23852728.

- ^ a b Sarbassov DD, Guertin DA, Ali SM, Sabatini DM (February 2005). "Phosphorylation and regulation of Akt/PKB by the rictor-mTOR complex". Science. 307 (5712): 1098–101. Bibcode:2005Sci...307.1098S. doi:10.1126/science.1106148. PMID 15718470. S2CID 45837814.

- ^ Stephens L, Anderson K, Stokoe D, Erdjument-Bromage H, Painter GF, Holmes AB, Gaffney PR, Reese CB, McCormick F, Tempst P, Coadwell J, Hawkins PT (January 1998). "Protein kinase B kinases that mediate phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate-dependent activation of protein kinase B". Science. 279 (5351): 710–4. Bibcode:1998Sci...279..710S. doi:10.1126/science.279.5351.710. PMID 9445477.

- ^ a b Lamming DW, Ye L, Katajisto P, Goncalves MD, Saitoh M, Stevens DM, Davis JG, Salmon AB, Richardson A, Ahima RS, Guertin DA, Sabatini DM, Baur JA (March 2012). "Rapamycin-induced insulin resistance is mediated by mTORC2 loss and uncoupled from longevity". Science. 335 (6076): 1638–43. Bibcode:2012Sci...335.1638L. doi:10.1126/science.1215135. PMC 3324089. PMID 22461615.

- ^ Zinzalla V, Stracka D, Oppliger W, Hall MN (March 2011). "Activation of mTORC2 by association with the ribosome". Cell. 144 (5): 757–68. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.014. PMID 21376236.

- ^ Zhang F, Zhang X, Li M, Chen P, Zhang B, Guo H, Cao W, Wei X, Cao X, Hao X, Zhang N (November 2010). "mTOR complex component Rictor interacts with PKCzeta and regulates cancer cell metastasis". Cancer Research. 70 (22): 9360–70. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-0207. PMID 20978191.

- ^ Guertin DA, Stevens DM, Thoreen CC, Burds AA, Kalaany NY, Moffat J, Brown M, Fitzgerald KJ, Sabatini DM (December 2006). "Ablation in mice of the mTORC components raptor, rictor, or mLST8 reveals that mTORC2 is required for signaling to Akt-FOXO and PKCalpha, but not S6K1". Developmental Cell. 11 (6): 859–71. doi:10.1016/j.devcel.2006.10.007. PMID 17141160.

- ^ Gu Y, Lindner J, Kumar A, Yuan W, Magnuson MA (March 2011). "Rictor/mTORC2 is essential for maintaining a balance between beta-cell proliferation and cell size". Diabetes. 60 (3): 827–37. doi:10.2337/db10-1194. PMC 3046843. PMID 21266327.

- ^ Lamming DW, Demirkan G, Boylan JM, Mihaylova MM, Peng T, Ferreira J, Neretti N, Salomon A, Sabatini DM, Gruppuso PA (January 2014). "Hepatic signaling by the mechanistic target of rapamycin complex 2 (mTORC2)". FASEB Journal. 28 (1): 300–15. doi:10.1096/fj.13-237743. PMC 3868844. PMID 24072782.

- ^ Kumar A, Lawrence JC, Jung DY, Ko HJ, Keller SR, Kim JK, Magnuson MA, Harris TE (June 2010). "Fat cell-specific ablation of rictor in mice impairs insulin-regulated fat cell and whole-body glucose and lipid metabolism". Diabetes. 59 (6): 1397–406. doi:10.2337/db09-1061. PMC 2874700. PMID 20332342.

- ^ Lamming DW, Mihaylova MM, Katajisto P, Baar EL, Yilmaz OH, Hutchins A, Gultekin Y, Gaither R, Sabatini DM (October 2014). "Depletion of Rictor, an essential protein component of mTORC2, decreases male lifespan". Aging Cell. 13 (5): 911–7. doi:10.1111/acel.12256. PMC 4172536. PMID 25059582.

- ^ Feldman ME, Apsel B, Uotila A, Loewith R, Knight ZA, Ruggero D, Shokat KM (February 2009). "Active-site inhibitors of mTOR target rapamycin-resistant outputs of mTORC1 and mTORC2". PLOS Biology. 7 (2): e38. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1000038. PMC 2637922. PMID 19209957.

- ^ Wu JJ, Liu J, Chen EB, Wang JJ, Cao L, Narayan N, Fergusson MM, Rovira II, Allen M, Springer DA, Lago CU, Zhang S, DuBois W, Ward T, deCabo R, Gavrilova O, Mock B, Finkel T (September 2013). "Increased mammalian lifespan and a segmental and tissue-specific slowing of aging after genetic reduction of mTOR expression". Cell Reports. 4 (5): 913–20. doi:10.1016/j.celrep.2013.07.030. PMC 3784301. PMID 23994476.

- ^ Lawlor MA, Mora A, Ashby PR, Williams MR, Murray-Tait V, Malone L, Prescott AR, Lucocq JM, Alessi DR (July 2002). "Essential role of PDK1 in regulating cell size and development in mice". The EMBO Journal. 21 (14): 3728–38. doi:10.1093/emboj/cdf387. PMC 126129. PMID 12110585.

- ^ Yang ZZ, Tschopp O, Baudry A, Dümmler B, Hynx D, Hemmings BA (April 2004). "Physiological functions of protein kinase B/Akt". Biochemical Society Transactions. 32 (Pt 2): 350–4. doi:10.1042/BST0320350. PMID 15046607.

- ^ Nojima A, Yamashita M, Yoshida Y, Shimizu I, Ichimiya H, Kamimura N, Kobayashi Y, Ohta S, Ishii N, Minamino T (2013-01-01). "Haploinsufficiency of akt1 prolongs the lifespan of mice". PLOS ONE. 8 (7): e69178. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...869178N. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0069178. PMC 3728301. PMID 23935948.

- ^ Crespo JL, Hall MN (December 2002). "Elucidating TOR signaling and rapamycin action: lessons from Saccharomyces cerevisiae". Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews. 66 (4): 579–91, table of contents. doi:10.1128/mmbr.66.4.579-591.2002. PMC 134654. PMID 12456783.

- ^ Peter GJ, Düring L, Ahmed A (March 2006). "Carbon catabolite repression regulates amino acid permeases in Saccharomyces cerevisiae via the TOR signaling pathway". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 281 (9): 5546–52. doi:10.1074/jbc.M513842200. PMID 16407266.

- ^ a b Powers RW, Kaeberlein M, Caldwell SD, Kennedy BK, Fields S (January 2006). "Extension of chronological life span in yeast by decreased TOR pathway signaling". Genes & Development. 20 (2): 174–84. doi:10.1101/gad.1381406. PMC 1356109. PMID 16418483.

- ^ a b Kaeberlein M, Powers RW, Steffen KK, Westman EA, Hu D, Dang N, Kerr EO, Kirkland KT, Fields S, Kennedy BK (November 2005). "Regulation of yeast replicative life span by TOR and Sch9 in response to nutrients". Science. 310 (5751): 1193–6. Bibcode:2005Sci...310.1193K. doi:10.1126/science.1115535. PMID 16293764. S2CID 42188272.

- ^ Jia K, Chen D, Riddle DL (August 2004). "The TOR pathway interacts with the insulin signaling pathway to regulate C. elegans larval development, metabolism and life span". Development. 131 (16): 3897–906. doi:10.1242/dev.01255. PMID 15253933.

- ^ Kapahi P, Zid BM, Harper T, Koslover D, Sapin V, Benzer S (May 2004). "Regulation of lifespan in Drosophila by modulation of genes in the TOR signaling pathway". Current Biology. 14 (10): 885–90. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2004.03.059. PMC 2754830. PMID 15186745.

- ^ Harrison DE, Strong R, Sharp ZD, Nelson JF, Astle CM, Flurkey K, Nadon NL, Wilkinson JE, Frenkel K, Carter CS, Pahor M, Javors MA, Fernandez E, Miller RA (July 2009). "Rapamycin fed late in life extends lifespan in genetically heterogeneous mice". Nature. 460 (7253): 392–5. Bibcode:2009Natur.460..392H. doi:10.1038/nature08221. PMC 2786175. PMID 19587680.

- ^ Miller RA, Harrison DE, Astle CM, Fernandez E, Flurkey K, Han M, Javors MA, Li X, Nadon NL, Nelson JF, Pletcher S, Salmon AB, Sharp ZD, Van Roekel S, Winkleman L, Strong R (June 2014). "Rapamycin-mediated lifespan increase in mice is dose and sex dependent and metabolically distinct from dietary restriction". Aging Cell. 13 (3): 468–77. doi:10.1111/acel.12194. PMC 4032600. PMID 24341993.

- ^ Fok WC, Chen Y, Bokov A, Zhang Y, Salmon AB, Diaz V, Javors M, Wood WH, Zhang Y, Becker KG, Pérez VI, Richardson A (2014-01-01). "Mice fed rapamycin have an increase in lifespan associated with major changes in the liver transcriptome". PLOS ONE. 9 (1): e83988. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...983988F. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0083988. PMC 3883653. PMID 24409289.

- ^ Arriola Apelo SI, Pumper CP, Baar EL, Cummings NE, Lamming DW (July 2016). "Intermittent Administration of Rapamycin Extends the Life Span of Female C57BL/6J Mice". The Journals of Gerontology. Series A, Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences. 71 (7): 876–81. doi:10.1093/gerona/glw064. PMC 4906329. PMID 27091134.

- ^ Popovich IG, Anisimov VN, Zabezhinski MA, Semenchenko AV, Tyndyk ML, Yurova MN, Blagosklonny MV (May 2014). "Lifespan extension and cancer prevention in HER-2/neu transgenic mice treated with low intermittent doses of rapamycin". Cancer Biology & Therapy. 15 (5): 586–92. doi:10.4161/cbt.28164. PMC 4026081. PMID 24556924.

- ^ Baar EL, Carbajal KA, Ong IM, Lamming DW (February 2016). "Sex- and tissue-specific changes in mTOR signaling with age in C57BL/6J mice". Aging Cell. 15 (1): 155–66. doi:10.1111/acel.12425. PMC 4717274. PMID 26695882.

- ^ Caron A, Richard D, Laplante M (Jul 2015). "The Roles of mTOR Complexes in Lipid Metabolism". Annual Review of Nutrition. 35: 321–48. doi:10.1146/annurev-nutr-071714-034355. PMID 26185979.

- ^ Cota D, Proulx K, Smith KA, Kozma SC, Thomas G, Woods SC, Seeley RJ (May 2006). "Hypothalamic mTOR signaling regulates food intake". Science. 312 (5775): 927–30. Bibcode:2006Sci...312..927C. doi:10.1126/science.1124147. PMID 16690869. S2CID 6526786.

- ^ a b Kriete A, Bosl WJ, Booker G (June 2010). "Rule-based cell systems model of aging using feedback loop motifs mediated by stress responses". PLOS Computational Biology. 6 (6): e1000820. Bibcode:2010PLSCB...6E0820K. doi:10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000820. PMC 2887462. PMID 20585546.

- ^ a b Schieke SM, Phillips D, McCoy JP, Aponte AM, Shen RF, Balaban RS, Finkel T (September 2006). "The mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathway regulates mitochondrial oxygen consumption and oxidative capacity". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 281 (37): 27643–52. doi:10.1074/jbc.M603536200. PMID 16847060.

- ^ Yessenkyzy A, Saliev T, Zhanaliyeva M, Nurgozhin T (2020). "Polyphenols as Caloric-Restriction Mimetics and Autophagy Inducers in Aging Research". Nutrients. 12 (5): 1344. doi:10.3390/nu12051344. PMC 7285205. PMID 32397145.

- ^ a b Laberge R, Sun Y, Orjalo AV, Patil CK, Campisi J (2015). "MTOR regulates the pro-tumorigenic senescence-associated secretory phenotype by promoting IL1A translation". Nature Cell Biology. 17 (8): 1049–1061. doi:10.1038/ncb3195. PMC 4691706. PMID 26147250.

- ^ Wang R, Yu Z, Sunchu B, Perez VI (2017). "Rapamycin inhibits the secretory phenotype of senescent cells by a Nrf2-independent mechanism". Aging Cell. 16 (3): 564–574. doi:10.1111/acel.12587. PMC 5418203. PMID 28371119.

- ^ Wang R, Sunchu B, Perez VI (2017). "Rapamycin and the inhibition of the secretory phenotype". Experimental Gerontology. 94: 89–92. doi:10.1016/j.exger.2017.01.026. PMID 28167236. S2CID 4960885.

- ^ Weichhart T (2018). "mTOR as Regulator of Lifespan, Aging, and Cellular Senescence: A Mini-Review". Gerontology. 84 (2): 127–134. doi:10.1159/000484629. PMC 6089343. PMID 29190625.

- ^ Xu K, Liu P, Wei W (December 2014). "mTOR signaling in tumorigenesis". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Reviews on Cancer. 1846 (2): 638–54. doi:10.1016/j.bbcan.2014.10.007. PMC 4261029. PMID 25450580.

- ^ Guertin DA, Sabatini DM (August 2005). "An expanding role for mTOR in cancer". Trends in Molecular Medicine. 11 (8): 353–61. doi:10.1016/j.molmed.2005.06.007. PMID 16002336.

- ^ Pópulo H, Lopes JM, Soares P (2012). "The mTOR signalling pathway in human cancer". International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 13 (2): 1886–918. doi:10.3390/ijms13021886. PMC 3291999. PMID 22408430.

- ^ Easton JB, Houghton PJ (October 2006). "mTOR and cancer therapy". Oncogene. 25 (48): 6436–46. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1209886. PMID 17041628.

- ^ Zoncu R, Efeyan A, Sabatini DM (January 2011). "mTOR: from growth signal integration to cancer, diabetes and ageing". Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 12 (1): 21–35. doi:10.1038/nrm3025. PMC 3390257. PMID 21157483.

- ^ Thomas GV, Tran C, Mellinghoff IK, Welsbie DS, Chan E, Fueger B, Czernin J, Sawyers CL (January 2006). "Hypoxia-inducible factor determines sensitivity to inhibitors of mTOR in kidney cancer". Nature Medicine. 12 (1): 122–7. doi:10.1038/nm1337. PMID 16341243. S2CID 1853822.

- ^ Nemazanyy I, Espeillac C, Pende M, Panasyuk G (August 2013). "Role of PI3K, mTOR and Akt2 signalling in hepatic tumorigenesis via the control of PKM2 expression". Biochemical Society Transactions. 41 (4): 917–22. doi:10.1042/BST20130034. PMID 23863156.

- ^ Tang G, Gudsnuk K, Kuo SH, Cotrina ML, Rosoklija G, Sosunov A, Sonders MS, Kanter E, Castagna C, Yamamoto A, Yue Z, Arancio O, Peterson BS, Champagne F, Dwork AJ, Goldman J, Sulzer D (September 2014). "Loss of mTOR-dependent macroautophagy causes autistic-like synaptic pruning deficits". Neuron. 83 (5): 1131–43. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2014.07.040. PMC 4159743. PMID 25155956.

- ^ Rosner M, Hanneder M, Siegel N, Valli A, Fuchs C, Hengstschläger M (June 2008). "The mTOR pathway and its role in human genetic diseases". Mutation Research. 659 (3): 284–92. doi:10.1016/j.mrrev.2008.06.001. PMID 18598780.

- ^ Li X, Alafuzoff I, Soininen H, Winblad B, Pei JJ (August 2005). "Levels of mTOR and its downstream targets 4E-BP1, eEF2, and eEF2 kinase in relationships with tau in Alzheimer's disease brain". The FEBS Journal. 272 (16): 4211–20. doi:10.1111/j.1742-4658.2005.04833.x. PMID 16098202. S2CID 43085490.

- ^ Chano T, Okabe H, Hulette CM (September 2007). "RB1CC1 insufficiency causes neuronal atrophy through mTOR signaling alteration and involved in the pathology of Alzheimer's diseases". Brain Research. 1168 (1168): 97–105. doi:10.1016/j.brainres.2007.06.075. PMID 17706618. S2CID 54255848.

- ^ Selkoe DJ (September 2008). "Soluble oligomers of the amyloid beta-protein impair synaptic plasticity and behavior". Behavioural Brain Research. 192 (1): 106–13. doi:10.1016/j.bbr.2008.02.016. PMC 2601528. PMID 18359102.

- ^ a b Oddo S (January 2012). "The role of mTOR signaling in Alzheimer disease". Frontiers in Bioscience. 4 (1): 941–52. doi:10.2741/s310. PMC 4111148. PMID 22202101.

- ^ a b An WL, Cowburn RF, Li L, Braak H, Alafuzoff I, Iqbal K, Iqbal IG, Winblad B, Pei JJ (August 2003). "Up-regulation of phosphorylated/activated p70 S6 kinase and its relationship to neurofibrillary pathology in Alzheimer's disease". The American Journal of Pathology. 163 (2): 591–607. doi:10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63687-5. PMC 1868198. PMID 12875979.

- ^ Zhang F, Beharry ZM, Harris TE, Lilly MB, Smith CD, Mahajan S, Kraft AS (May 2009). "PIM1 protein kinase regulates PRAS40 phosphorylation and mTOR activity in FDCP1 cells". Cancer Biology & Therapy. 8 (9): 846–53. doi:10.4161/cbt.8.9.8210. PMID 19276681.

- ^ Koo EH, Squazzo SL (July 1994). "Evidence that production and release of amyloid beta-protein involves the endocytic pathway". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 269 (26): 17386–9. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(17)32449-3. PMID 8021238.

- ^ a b c Caccamo A, Majumder S, Richardson A, Strong R, Oddo S (April 2010). "Molecular interplay between mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), amyloid-beta, and Tau: effects on cognitive impairments". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 285 (17): 13107–20. doi:10.1074/jbc.M110.100420. PMC 2857107. PMID 20178983.

- ^ Lafay-Chebassier C, Paccalin M, Page G, Barc-Pain S, Perault-Pochat MC, Gil R, Pradier L, Hugon J (July 2005). "mTOR/p70S6k signalling alteration by Abeta exposure as well as in APP-PS1 transgenic models and in patients with Alzheimer's disease". Journal of Neurochemistry. 94 (1): 215–25. doi:10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03187.x. PMID 15953364. S2CID 8464608.

- ^ a b c d Caccamo A, Maldonado MA, Majumder S, Medina DX, Holbein W, Magrí A, Oddo S (March 2011). "Naturally secreted amyloid-beta increases mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) activity via a PRAS40-mediated mechanism". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 286 (11): 8924–32. doi:10.1074/jbc.M110.180638. PMC 3058958. PMID 21266573.

- ^ Sancak Y, Thoreen CC, Peterson TR, Lindquist RA, Kang SA, Spooner E, Carr SA, Sabatini DM (March 2007). "PRAS40 is an insulin-regulated inhibitor of the mTORC1 protein kinase". Molecular Cell. 25 (6): 903–15. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2007.03.003. PMID 17386266.

- ^ Wang L, Harris TE, Roth RA, Lawrence JC (July 2007). "PRAS40 regulates mTORC1 kinase activity by functioning as a direct inhibitor of substrate binding". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 282 (27): 20036–44. doi:10.1074/jbc.M702376200. PMID 17510057.

- ^ Pei JJ, Hugon J (December 2008). "mTOR-dependent signalling in Alzheimer's disease". Journal of Cellular and Molecular Medicine. 12 (6B): 2525–32. doi:10.1111/j.1582-4934.2008.00509.x. PMC 3828871. PMID 19210753.

- ^ Meske V, Albert F, Ohm TG (January 2008). "Coupling of mammalian target of rapamycin with phosphoinositide 3-kinase signaling pathway regulates protein phosphatase 2A- and glycogen synthase kinase-3 -dependent phosphorylation of Tau". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 283 (1): 100–9. doi:10.1074/jbc.M704292200. PMID 17971449.

- ^ Janssens V, Goris J (February 2001). "Protein phosphatase 2A: a highly regulated family of serine/threonine phosphatases implicated in cell growth and signalling". The Biochemical Journal. 353 (Pt 3): 417–39. doi:10.1042/0264-6021:3530417. PMC 1221586. PMID 11171037.

- ^ Morita T, Sobue K (October 2009). "Specification of neuronal polarity regulated by local translation of CRMP2 and Tau via the mTOR-p70S6K pathway". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 284 (40): 27734–45. doi:10.1074/jbc.M109.008177. PMC 2785701. PMID 19648118.

- ^ Puighermanal E, Marsicano G, Busquets-Garcia A, Lutz B, Maldonado R, Ozaita A (September 2009). "Cannabinoid modulation of hippocampal long-term memory is mediated by mTOR signaling". Nature Neuroscience. 12 (9): 1152–8. doi:10.1038/nn.2369. PMID 19648913. S2CID 9584832.

- ^ Tischmeyer W, Schicknick H, Kraus M, Seidenbecher CI, Staak S, Scheich H, Gundelfinger ED (August 2003). "Rapamycin-sensitive signalling in long-term consolidation of auditory cortex-dependent memory". The European Journal of Neuroscience. 18 (4): 942–50. doi:10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02820.x. PMID 12925020. S2CID 2780242.

- ^ Hoeffer CA, Klann E (February 2010). "mTOR signaling: at the crossroads of plasticity, memory and disease". Trends in Neurosciences. 33 (2): 67–75. doi:10.1016/j.tins.2009.11.003. PMC 2821969. PMID 19963289.

- ^ Kelleher RJ, Govindarajan A, Jung HY, Kang H, Tonegawa S (February 2004). "Translational control by MAPK signaling in long-term synaptic plasticity and memory". Cell. 116 (3): 467–79. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(04)00115-1. PMID 15016380.

- ^ Ehninger D, Han S, Shilyansky C, Zhou Y, Li W, Kwiatkowski DJ, Ramesh V, Silva AJ (August 2008). "Reversal of learning deficits in a Tsc2+/- mouse model of tuberous sclerosis". Nature Medicine. 14 (8): 843–8. doi:10.1038/nm1788. PMC 2664098. PMID 18568033.

- ^ Moreno JA, Radford H, Peretti D, Steinert JR, Verity N, Martin MG, Halliday M, Morgan J, Dinsdale D, Ortori CA, Barrett DA, Tsaytler P, Bertolotti A, Willis AE, Bushell M, Mallucci GR (May 2012). "Sustained translational repression by eIF2α-P mediates prion neurodegeneration". Nature. 485 (7399): 507–11. Bibcode:2012Natur.485..507M. doi:10.1038/nature11058. PMC 3378208. PMID 22622579.

- ^ Díaz-Troya S, Pérez-Pérez ME, Florencio FJ, Crespo JL (October 2008). "The role of TOR in autophagy regulation from yeast to plants and mammals". Autophagy. 4 (7): 851–65. doi:10.4161/auto.6555. PMID 18670193.

- ^ McCray BA, Taylor JP (December 2008). "The role of autophagy in age-related neurodegeneration". Neuro-Signals. 16 (1): 75–84. doi:10.1159/000109761. PMID 18097162.

- ^ Nedelsky NB, Todd PK, Taylor JP (December 2008). "Autophagy and the ubiquitin-proteasome system: collaborators in neuroprotection". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Basis of Disease. 1782 (12): 691–9. doi:10.1016/j.bbadis.2008.10.002. PMC 2621359. PMID 18930136.

- ^ Rubinsztein DC (October 2006). "The roles of intracellular protein-degradation pathways in neurodegeneration". Nature. 443 (7113): 780–6. Bibcode:2006Natur.443..780R. doi:10.1038/nature05291. PMID 17051204. S2CID 4411895.

- ^ Oddo S (April 2008). "The ubiquitin-proteasome system in Alzheimer's disease". Journal of Cellular and Molecular Medicine. 12 (2): 363–73. doi:10.1111/j.1582-4934.2008.00276.x. PMC 3822529. PMID 18266959.

- ^ Li X, Li H, Li XJ (November 2008). "Intracellular degradation of misfolded proteins in polyglutamine neurodegenerative diseases". Brain Research Reviews. 59 (1): 245–52. doi:10.1016/j.brainresrev.2008.08.003. PMC 2577582. PMID 18773920.

- ^ Caccamo A, Majumder S, Deng JJ, Bai Y, Thornton FB, Oddo S (October 2009). "Rapamycin rescues TDP-43 mislocalization and the associated low molecular mass neurofilament instability". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 284 (40): 27416–24. doi:10.1074/jbc.M109.031278. PMC 2785671. PMID 19651785.

- ^ Ravikumar B, Vacher C, Berger Z, Davies JE, Luo S, Oroz LG, Scaravilli F, Easton DF, Duden R, O'Kane CJ, Rubinsztein DC (June 2004). "Inhibition of mTOR induces autophagy and reduces toxicity of polyglutamine expansions in fly and mouse models of Huntington disease". Nature Genetics. 36 (6): 585–95. doi:10.1038/ng1362. PMID 15146184.

- ^ Rami A (October 2009). "Review: autophagy in neurodegeneration: firefighter and/or incendiarist?". Neuropathology and Applied Neurobiology. 35 (5): 449–61. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2990.2009.01034.x. PMID 19555462.

- ^ Völkl, Simon 등"과잉 활성 mTOR 경로는 자가면역 림프증식증후군의 림프증식 및 비정상적인 분화를 촉진합니다."블러드, 미국 혈액학회지 128.2 (2016) : 227-238.https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2015-11-685024

- ^ 아레나스, 다니엘 J. 등"특발성 다심성 캐슬맨 질환에서 mTOR 활성화 증가"혈액 135.19 (2020): 1673-1684.https://doi.org/10.1182/blood.2019002792

- ^ 엘살렘, 무나 등"이식 후 림프 증식 장애에서 mTOR 신호 경로의 구성 활성화." 실험실 조사 87.1(2007): 29-39.https://doi.org/10.1038/labinvest.3700494

- ^ a b c d Brook MS, Wilkinson DJ, Phillips BE, Perez-Schindler J, Philp A, Smith K, Atherton PJ (January 2016). "Skeletal muscle homeostasis and plasticity in youth and ageing: impact of nutrition and exercise". Acta Physiologica. 216 (1): 15–41. doi:10.1111/apha.12532. PMC 4843955. PMID 26010896.

- ^ a b Brioche T, Pagano AF, Py G, Chopard A (April 2016). "Muscle wasting and aging: Experimental models, fatty infiltrations, and prevention" (PDF). Molecular Aspects of Medicine. 50: 56–87. doi:10.1016/j.mam.2016.04.006. PMID 27106402.

- ^ Drummond MJ, Dreyer HC, Fry CS, Glynn EL, Rasmussen BB (April 2009). "Nutritional and contractile regulation of human skeletal muscle protein synthesis and mTORC1 signaling". Journal of Applied Physiology. 106 (4): 1374–84. doi:10.1152/japplphysiol.91397.2008. PMC 2698645. PMID 19150856.

- ^ Salto R, Vílchez JD, Girón MD, Cabrera E, Campos N, Manzano M, Rueda R, López-Pedrosa JM (2015). "β-Hydroxy-β-Methylbutyrate (HMB) Promotes Neurite Outgrowth in Neuro2a Cells". PLOS ONE. 10 (8): e0135614. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1035614S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0135614. PMC 4534402. PMID 26267903.

- ^ Kougias DG, Nolan SO, Koss WA, Kim T, Hankosky ER, Gulley JM, Juraska JM (April 2016). "Beta-hydroxy-beta-methylbutyrate ameliorates aging effects in the dendritic tree of pyramidal neurons in the medial prefrontal cortex of both male and female rats". Neurobiology of Aging. 40: 78–85. doi:10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2016.01.004. PMID 26973106. S2CID 3953100.

- ^ a b Phillips SM (May 2014). "A brief review of critical processes in exercise-induced muscular hypertrophy". Sports Med. 44 Suppl 1: S71–S77. doi:10.1007/s40279-014-0152-3. PMC 4008813. PMID 24791918.

- ^ a b c d e f g Jia J, Abudu YP, Claude-Taupin A, Gu Y, Kumar S, Choi SW, Peters R, Mudd MH, Allers L, Salemi M, Phinney B, Johansen T, Deretic V (April 2018). "Galectins Control mTOR in Response to Endomembrane Damage". Molecular Cell. 70 (1): 120–135.e8. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2018.03.009. PMC 5911935. PMID 29625033.

- ^ Noda T, Ohsumi Y (February 1998). "Tor, a phosphatidylinositol kinase homologue, controls autophagy in yeast". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 273 (7): 3963–6. doi:10.1074/jbc.273.7.3963. PMID 9461583.

- ^ Dubouloz F, Deloche O, Wanke V, Cameroni E, De Virgilio C (July 2005). "The TOR and EGO protein complexes orchestrate microautophagy in yeast". Molecular Cell. 19 (1): 15–26. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2005.05.020. PMID 15989961.

- ^ a b Ganley IG, Lam du H, Wang J, Ding X, Chen S, Jiang X (May 2009). "ULK1.ATG13.FIP200 complex mediates mTOR signaling and is essential for autophagy". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 284 (18): 12297–305. doi:10.1074/jbc.M900573200. PMC 2673298. PMID 19258318.

- ^ a b Jung CH, Jun CB, Ro SH, Kim YM, Otto NM, Cao J, Kundu M, Kim DH (April 2009). "ULK-Atg13-FIP200 complexes mediate mTOR signaling to the autophagy machinery". Molecular Biology of the Cell. 20 (7): 1992–2003. doi:10.1091/mbc.e08-12-1249. PMC 2663920. PMID 19225151.

- ^ a b Hosokawa N, Hara T, Kaizuka T, Kishi C, Takamura A, Miura Y, Iemura S, Natsume T, Takehana K, Yamada N, Guan JL, Oshiro N, Mizushima N (April 2009). "Nutrient-dependent mTORC1 association with the ULK1-Atg13-FIP200 complex required for autophagy". Molecular Biology of the Cell. 20 (7): 1981–91. doi:10.1091/mbc.e08-12-1248. PMC 2663915. PMID 19211835.

- ^ Hasegawa J, Maejima I, Iwamoto R, Yoshimori T (March 2015). "Selective autophagy: lysophagy". Methods. 75: 128–32. doi:10.1016/j.ymeth.2014.12.014. PMID 25542097.

- ^ Fraiberg M, Elazar Z (October 2016). "A TRIM16-Galactin3 Complex Mediates Autophagy of Damaged Endomembranes". Developmental Cell. 39 (1): 1–2. doi:10.1016/j.devcel.2016.09.025. PMID 27728777.

- ^ a b c Chauhan S, Kumar S, Jain A, Ponpuak M, Mudd MH, Kimura T, Choi SW, Peters R, Mandell M, Bruun JA, Johansen T, Deretic V (October 2016). "TRIMs and Galectins Globally Cooperate and TRIM16 and Galectin-3 Co-direct Autophagy in Endomembrane Damage Homeostasis". Developmental Cell. 39 (1): 13–27. doi:10.1016/j.devcel.2016.08.003. PMC 5104201. PMID 27693506.

- ^ Nishimura T, Kaizuka T, Cadwell K, Sahani MH, Saitoh T, Akira S, Virgin HW, Mizushima N (March 2013). "FIP200 regulates targeting of Atg16L1 to the isolation membrane". EMBO Reports. 14 (3): 284–91. doi:10.1038/embor.2013.6. PMC 3589088. PMID 23392225.

- ^ Gammoh N, Florey O, Overholtzer M, Jiang X (February 2013). "Interaction between FIP200 and ATG16L1 distinguishes ULK1 complex-dependent and -independent autophagy". Nature Structural & Molecular Biology. 20 (2): 144–9. doi:10.1038/nsmb.2475. PMC 3565010. PMID 23262492.

- ^ a b c Fujita N, Morita E, Itoh T, Tanaka A, Nakaoka M, Osada Y, Umemoto T, Saitoh T, Nakatogawa H, Kobayashi S, Haraguchi T, Guan JL, Iwai K, Tokunaga F, Saito K, Ishibashi K, Akira S, Fukuda M, Noda T, Yoshimori T (October 2013). "Recruitment of the autophagic machinery to endosomes during infection is mediated by ubiquitin". The Journal of Cell Biology. 203 (1): 115–28. doi:10.1083/jcb.201304188. PMC 3798248. PMID 24100292.

- ^ Park JM, Jung CH, Seo M, Otto NM, Grunwald D, Kim KH, Moriarity B, Kim YM, Starker C, Nho RS, Voytas D, Kim DH (2016-03-03). "The ULK1 complex mediates MTORC1 signaling to the autophagy initiation machinery via binding and phosphorylating ATG14". Autophagy. 12 (3): 547–64. doi:10.1080/15548627.2016.1140293. PMC 4835982. PMID 27046250.

- ^ Dooley HC, Razi M, Polson HE, Girardin SE, Wilson MI, Tooze SA (July 2014). "WIPI2 links LC3 conjugation with PI3P, autophagosome formation, and pathogen clearance by recruiting Atg12-5-16L1". Molecular Cell. 55 (2): 238–52. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2014.05.021. PMC 4104028. PMID 24954904.

- ^ Kim J, Kundu M, Viollet B, Guan KL (February 2011). "AMPK and mTOR regulate autophagy through direct phosphorylation of Ulk1". Nature Cell Biology. 13 (2): 132–41. doi:10.1038/ncb2152. PMC 3987946. PMID 21258367.

- ^ Kim J, Kim YC, Fang C, Russell RC, Kim JH, Fan W, Liu R, Zhong Q, Guan KL (January 2013). "Differential regulation of distinct Vps34 complexes by AMPK in nutrient stress and autophagy". Cell. 152 (1–2): 290–303. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2012.12.016. PMC 3587159. PMID 23332761.

- ^ Gwinn DM, Shackelford DB, Egan DF, Mihaylova MM, Mery A, Vasquez DS, Turk BE, Shaw RJ (April 2008). "AMPK phosphorylation of raptor mediates a metabolic checkpoint". Molecular Cell. 30 (2): 214–26. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2008.03.003. PMC 2674027. PMID 18439900.

- ^ Inoki K, Zhu T, Guan KL (November 2003). "TSC2 mediates cellular energy response to control cell growth and survival". Cell. 115 (5): 577–90. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00929-2. PMID 14651849.

- ^ Yoshida Y, Yasuda S, Fujita T, Hamasaki M, Murakami A, Kawawaki J, Iwai K, Saeki Y, Yoshimori T, Matsuda N, Tanaka K (August 2017). "FBXO27 directs damaged lysosomes for autophagy". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 114 (32): 8574–8579. doi:10.1073/pnas.1702615114. PMC 5559013. PMID 28743755.

- ^ Jimenez SA, Cronin PM, Koenig AS, O'Brien MS, Castro SV (15 February 2012). Varga J, Talavera F, Goldberg E, Mechaber AJ, Diamond HS (eds.). "Scleroderma". Medscape Reference. WebMD. Retrieved 5 March 2014.

- ^ Hajj-ali RA (June 2013). "Systemic Sclerosis". Merck Manual Professional. Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp. Retrieved 5 March 2014.

- ^ "Mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitors in solid tumours". Pharmaceutical Journal. Retrieved 2018-10-18.

- ^ Faivre S, Kroemer G, Raymond E (August 2006). "Current development of mTOR inhibitors as anticancer agents". Nature Reviews. Drug Discovery. 5 (8): 671–88. doi:10.1038/nrd2062. PMID 16883305. S2CID 27952376.

- ^ Hasty P (February 2010). "Rapamycin: the cure for all that ails". Journal of Molecular Cell Biology. 2 (1): 17–9. doi:10.1093/jmcb/mjp033. PMID 19805415.

- ^ Bové J, Martínez-Vicente M, Vila M (August 2011). "Fighting neurodegeneration with rapamycin: mechanistic insights". Nature Reviews. Neuroscience. 12 (8): 437–52. doi:10.1038/nrn3068. PMID 21772323. S2CID 205506774.

- ^ Mannick JB, Morris M, Hockey HP, Roma G, Beibel M, Kulmatycki K, Watkins M, Shavlakadze T, Zhou W, Quinn D, Glass DJ, Klickstein LB (July 2018). "TORC1 inhibition enhances immune function and reduces infections in the elderly". Science Translational Medicine. 10 (449): eaaq1564. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.aaq1564. PMID 29997249.

- ^ Estrela JM, Ortega A, Mena S, Rodriguez ML, Asensi M (2013). "Pterostilbene: Biomedical applications". Critical Reviews in Clinical Laboratory Sciences. 50 (3): 65–78. doi:10.3109/10408363.2013.805182. PMID 23808710. S2CID 45618964.

- ^ McCubrey JA, Lertpiriyapong K, Steelman LS, Abrams SL, Yang LV, Murata RM, et al. (June 2017). "Effects of resveratrol, curcumin, berberine and other nutraceuticals on aging, cancer development, cancer stem cells and microRNAs". Aging. 9 (6): 1477–1536. doi:10.18632/aging.101250. PMC 5509453. PMID 28611316.

- ^ Malavolta M, Bracci M, Santarelli L, Sayeed MA, Pierpaoli E, Giacconi R, et al. (2018). "Inducers of Senescence, Toxic Compounds, and Senolytics: The Multiple Faces of Nrf2-Activating Phytochemicals in Cancer Adjuvant Therapy". Mediators of Inflammation. 2018: 4159013. doi:10.1155/2018/4159013. PMC 5829354. PMID 29618945.

- ^ Gómez-Linton DR, Alavez S, Alarcón-Aguilar A, López-Diazguerrero NE, Konigsberg M, Pérez-Flores LJ (October 2019). "Some naturally occurring compounds that increase longevity and stress resistance in model organisms of aging". Biogerontology. 20 (5): 583–603. doi:10.1007/s10522-019-09817-2. PMID 31187283. S2CID 184483900.

- ^ Li W, Qin L, Feng R, Hu G, Sun H, He Y, Zhang R (July 2019). "Emerging senolytic agents derived from natural products". Mechanisms of Ageing and Development. 181: 1–6. doi:10.1016/j.mad.2019.05.001. PMID 31077707. S2CID 147704626.

- ^ "mTOR protein interactors". Human Protein Reference Database. Johns Hopkins University and the Institute of Bioinformatics. Retrieved 2010-12-06.

- ^ Kumar V, Sabatini D, Pandey P, Gingras AC, Majumder PK, Kumar M, Yuan ZM, Carmichael G, Weichselbaum R, Sonenberg N, Kufe D, Kharbanda S (April 2000). "Regulation of the rapamycin and FKBP-target 1/mammalian target of rapamycin and cap-dependent initiation of translation by the c-Abl protein-tyrosine kinase". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 275 (15): 10779–87. doi:10.1074/jbc.275.15.10779. PMID 10753870.

- ^ Sekulić A, Hudson CC, Homme JL, Yin P, Otterness DM, Karnitz LM, Abraham RT (July 2000). "A direct linkage between the phosphoinositide 3-kinase-AKT signaling pathway and the mammalian target of rapamycin in mitogen-stimulated and transformed cells". Cancer Research. 60 (13): 3504–13. PMID 10910062.

- ^ Cheng SW, Fryer LG, Carling D, Shepherd PR (April 2004). "Thr2446 is a novel mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) phosphorylation site regulated by nutrient status". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 279 (16): 15719–22. doi:10.1074/jbc.C300534200. PMID 14970221.

- ^ Choi JH, Bertram PG, Drenan R, Carvalho J, Zhou HH, Zheng XF (October 2002). "The FKBP12-rapamycin-associated protein (FRAP) is a CLIP-170 kinase". EMBO Reports. 3 (10): 988–94. doi:10.1093/embo-reports/kvf197. PMC 1307618. PMID 12231510.

- ^ Harris TE, Chi A, Shabanowitz J, Hunt DF, Rhoads RE, Lawrence JC (April 2006). "mTOR-dependent stimulation of the association of eIF4G and eIF3 by insulin". The EMBO Journal. 25 (8): 1659–68. doi:10.1038/sj.emboj.7601047. PMC 1440840. PMID 16541103.

- ^ a b Schalm SS, Fingar DC, Sabatini DM, Blenis J (May 2003). "TOS motif-mediated raptor binding regulates 4E-BP1 multisite phosphorylation and function". Current Biology. 13 (10): 797–806. doi:10.1016/S0960-9822(03)00329-4. PMID 12747827.

- ^ a b c Hara K, Maruki Y, Long X, Yoshino K, Oshiro N, Hidayat S, Tokunaga C, Avruch J, Yonezawa K (July 2002). "Raptor, a binding partner of target of rapamycin (TOR), mediates TOR action". Cell. 110 (2): 177–89. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(02)00833-4. PMID 12150926.

- ^ a b Wang L, Rhodes CJ, Lawrence JC (August 2006). "Activation of mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) by insulin is associated with stimulation of 4EBP1 binding to dimeric mTOR complex 1". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 281 (34): 24293–303. doi:10.1074/jbc.M603566200. PMID 16798736.

- ^ a b c Long X, Lin Y, Ortiz-Vega S, Yonezawa K, Avruch J (April 2005). "Rheb binds and regulates the mTOR kinase". Current Biology. 15 (8): 702–13. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2005.02.053. PMID 15854902.

- ^ a b Takahashi T, Hara K, Inoue H, Kawa Y, Tokunaga C, Hidayat S, Yoshino K, Kuroda Y, Yonezawa K (September 2000). "Carboxyl-terminal region conserved among phosphoinositide-kinase-related kinases is indispensable for mTOR function in vivo and in vitro". Genes to Cells. 5 (9): 765–75. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2443.2000.00365.x. PMID 10971657.

- ^ a b Burnett PE, Barrow RK, Cohen NA, Snyder SH, Sabatini DM (February 1998). "RAFT1 phosphorylation of the translational regulators p70 S6 kinase and 4E-BP1". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 95 (4): 1432–7. Bibcode:1998PNAS...95.1432B. doi:10.1073/pnas.95.4.1432. PMC 19032. PMID 9465032.

- ^ Wang X, Beugnet A, Murakami M, Yamanaka S, Proud CG (April 2005). "Distinct signaling events downstream of mTOR cooperate to mediate the effects of amino acids and insulin on initiation factor 4E-binding proteins". Molecular and Cellular Biology. 25 (7): 2558–72. doi:10.1128/MCB.25.7.2558-2572.2005. PMC 1061630. PMID 15767663.

- ^ Choi J, Chen J, Schreiber SL, Clardy J (July 1996). "Structure of the FKBP12-rapamycin complex interacting with the binding domain of human FRAP". Science. 273 (5272): 239–42. Bibcode:1996Sci...273..239C. doi:10.1126/science.273.5272.239. PMID 8662507. S2CID 27706675.

- ^ Luker KE, Smith MC, Luker GD, Gammon ST, Piwnica-Worms H, Piwnica-Worms D (August 2004). "Kinetics of regulated protein-protein interactions revealed with firefly luciferase complementation imaging in cells and living animals". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 101 (33): 12288–93. Bibcode:2004PNAS..10112288L. doi:10.1073/pnas.0404041101. PMC 514471. PMID 15284440.

- ^ Banaszynski LA, Liu CW, Wandless TJ (April 2005). "Characterization of the FKBP.rapamycin.FRB ternary complex". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 127 (13): 4715–21. doi:10.1021/ja043277y. PMID 15796538.

- ^ Sabers CJ, Martin MM, Brunn GJ, Williams JM, Dumont FJ, Wiederrecht G, Abraham RT (January 1995). "Isolation of a protein target of the FKBP12-rapamycin complex in mammalian cells". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 270 (2): 815–22. doi:10.1074/jbc.270.2.815. PMID 7822316.

- ^ Sabatini DM, Barrow RK, Blackshaw S, Burnett PE, Lai MM, Field ME, Bahr BA, Kirsch J, Betz H, Snyder SH (May 1999). "Interaction of RAFT1 with gephyrin required for rapamycin-sensitive signaling". Science. 284 (5417): 1161–4. Bibcode:1999Sci...284.1161S. doi:10.1126/science.284.5417.1161. PMID 10325225.

- ^ Ha SH, Kim DH, Kim IS, Kim JH, Lee MN, Lee HJ, Kim JH, Jang SK, Suh PG, Ryu SH (December 2006). "PLD2 forms a functional complex with mTOR/raptor to transduce mitogenic signals". Cellular Signalling. 18 (12): 2283–91. doi:10.1016/j.cellsig.2006.05.021. PMID 16837165.

- ^ Buerger C, DeVries B, Stambolic V (June 2006). "Localization of Rheb to the endomembrane is critical for its signaling function". Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 344 (3): 869–80. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.03.220. PMID 16631613.

- ^ a b Jacinto E, Facchinetti V, Liu D, Soto N, Wei S, Jung SY, Huang Q, Qin J, Su B (October 2006). "SIN1/MIP1 maintains rictor-mTOR complex integrity and regulates Akt phosphorylation and substrate specificity". Cell. 127 (1): 125–37. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2006.08.033. PMID 16962653.

- ^ McMahon LP, Yue W, Santen RJ, Lawrence JC (January 2005). "Farnesylthiosalicylic acid inhibits mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) activity both in cells and in vitro by promoting dissociation of the mTOR-raptor complex". Molecular Endocrinology. 19 (1): 175–83. doi:10.1210/me.2004-0305. PMID 15459249.

- ^ Oshiro N, Yoshino K, Hidayat S, Tokunaga C, Hara K, Eguchi S, Avruch J, Yonezawa K (April 2004). "Dissociation of raptor from mTOR is a mechanism of rapamycin-induced inhibition of mTOR function". Genes to Cells. 9 (4): 359–66. doi:10.1111/j.1356-9597.2004.00727.x. PMID 15066126.

- ^ Kawai S, Enzan H, Hayashi Y, Jin YL, Guo LM, Miyazaki E, Toi M, Kuroda N, Hiroi M, Saibara T, Nakayama H (July 2003). "Vinculin: a novel marker for quiescent and activated hepatic stellate cells in human and rat livers". Virchows Archiv. 443 (1): 78–86. doi:10.1007/s00428-003-0804-4. PMID 12719976. S2CID 21552704.

- ^ Choi KM, McMahon LP, Lawrence JC (May 2003). "Two motifs in the translational repressor PHAS-I required for efficient phosphorylation by mammalian target of rapamycin and for recognition by raptor". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 278 (22): 19667–73. doi:10.1074/jbc.M301142200. PMID 12665511.

- ^ a b Nojima H, Tokunaga C, Eguchi S, Oshiro N, Hidayat S, Yoshino K, Hara K, Tanaka N, Avruch J, Yonezawa K (May 2003). "The mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) partner, raptor, binds the mTOR substrates p70 S6 kinase and 4E-BP1 through their TOR signaling (TOS) motif". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 278 (18): 15461–4. doi:10.1074/jbc.C200665200. PMID 12604610.

- ^ a b Sarbassov DD, Ali SM, Sengupta S, Sheen JH, Hsu PP, Bagley AF, Markhard AL, Sabatini DM (April 2006). "Prolonged rapamycin treatment inhibits mTORC2 assembly and Akt/PKB". Molecular Cell. 22 (2): 159–68. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2006.03.029. PMID 16603397.

- ^ Tzatsos A, Kandror KV (January 2006). "Nutrients suppress phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt signaling via raptor-dependent mTOR-mediated insulin receptor substrate 1 phosphorylation". Molecular and Cellular Biology. 26 (1): 63–76. doi:10.1128/MCB.26.1.63-76.2006. PMC 1317643. PMID 16354680.

- ^ a b c Sarbassov DD, Sabatini DM (November 2005). "Redox regulation of the nutrient-sensitive raptor-mTOR pathway and complex". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 280 (47): 39505–9. doi:10.1074/jbc.M506096200. PMID 16183647.

- ^ a b Yang Q, Inoki K, Ikenoue T, Guan KL (October 2006). "Identification of Sin1 as an essential TORC2 component required for complex formation and kinase activity". Genes & Development. 20 (20): 2820–32. doi:10.1101/gad.1461206. PMC 1619946. PMID 17043309.

- ^ Kumar V, Pandey P, Sabatini D, Kumar M, Majumder PK, Bharti A, Carmichael G, Kufe D, Kharbanda S (March 2000). "Functional interaction between RAFT1/FRAP/mTOR and protein kinase cdelta in the regulation of cap-dependent initiation of translation". The EMBO Journal. 19 (5): 1087–97. doi:10.1093/emboj/19.5.1087. PMC 305647. PMID 10698949.

- ^ Long X, Ortiz-Vega S, Lin Y, Avruch J (June 2005). "Rheb binding to mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) is regulated by amino acid sufficiency". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 280 (25): 23433–6. doi:10.1074/jbc.C500169200. PMID 15878852.

- ^ Smith EM, Finn SG, Tee AR, Browne GJ, Proud CG (May 2005). "The tuberous sclerosis protein TSC2 is not required for the regulation of the mammalian target of rapamycin by amino acids and certain cellular stresses". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 280 (19): 18717–27. doi:10.1074/jbc.M414499200. PMID 15772076.

- ^ Bernardi R, Guernah I, Jin D, Grisendi S, Alimonti A, Teruya-Feldstein J, Cordon-Cardo C, Simon MC, Rafii S, Pandolfi PP (August 2006). "PML inhibits HIF-1alpha translation and neoangiogenesis through repression of mTOR". Nature. 442 (7104): 779–85. Bibcode:2006Natur.442..779B. doi:10.1038/nature05029. PMID 16915281. S2CID 4427427.

- ^ Saitoh M, Pullen N, Brennan P, Cantrell D, Dennis PB, Thomas G (May 2002). "Regulation of an activated S6 kinase 1 variant reveals a novel mammalian target of rapamycin phosphorylation site". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 277 (22): 20104–12. doi:10.1074/jbc.M201745200. PMID 11914378.

- ^ Chiang GG, Abraham RT (July 2005). "Phosphorylation of mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) at Ser-2448 is mediated by p70S6 kinase". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 280 (27): 25485–90. doi:10.1074/jbc.M501707200. PMID 15899889.

- ^ Holz MK, Blenis J (July 2005). "Identification of S6 kinase 1 as a novel mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR)-phosphorylating kinase". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 280 (28): 26089–93. doi:10.1074/jbc.M504045200. PMID 15905173.

- ^ Isotani S, Hara K, Tokunaga C, Inoue H, Avruch J, Yonezawa K (November 1999). "Immunopurified mammalian target of rapamycin phosphorylates and activates p70 S6 kinase alpha in vitro". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 274 (48): 34493–8. doi:10.1074/jbc.274.48.34493. PMID 10567431.

- ^ Toral-Barza L, Zhang WG, Lamison C, Larocque J, Gibbons J, Yu K (June 2005). "Characterization of the cloned full-length and a truncated human target of rapamycin: activity, specificity, and enzyme inhibition as studied by a high capacity assay". Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 332 (1): 304–10. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.04.117. PMID 15896331.

- ^ Ali SM, Sabatini DM (May 2005). "Structure of S6 kinase 1 determines whether raptor-mTOR or rictor-mTOR phosphorylates its hydrophobic motif site". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 280 (20): 19445–8. doi:10.1074/jbc.C500125200. PMID 15809305.

- ^ Edinger AL, Linardic CM, Chiang GG, Thompson CB, Abraham RT (December 2003). "Differential effects of rapamycin on mammalian target of rapamycin signaling functions in mammalian cells". Cancer Research. 63 (23): 8451–60. PMID 14679009.

- ^ Leone M, Crowell KJ, Chen J, Jung D, Chiang GG, Sareth S, Abraham RT, Pellecchia M (August 2006). "The FRB domain of mTOR: NMR solution structure and inhibitor design". Biochemistry. 45 (34): 10294–302. doi:10.1021/bi060976+. PMID 16922504.

- ^ Kristof AS, Marks-Konczalik J, Billings E, Moss J (September 2003). "Stimulation of signal transducer and activator of transcription-1 (STAT1)-dependent gene transcription by lipopolysaccharide and interferon-gamma is regulated by mammalian target of rapamycin". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 278 (36): 33637–44. doi:10.1074/jbc.M301053200. PMID 12807916.

- ^ Yokogami K, Wakisaka S, Avruch J, Reeves SA (January 2000). "Serine phosphorylation and maximal activation of STAT3 during CNTF signaling is mediated by the rapamycin target mTOR". Current Biology. 10 (1): 47–50. doi:10.1016/S0960-9822(99)00268-7. PMID 10660304.

- ^ Kusaba H, Ghosh P, Derin R, Buchholz M, Sasaki C, Madara K, Longo DL (January 2005). "Interleukin-12-induced interferon-gamma production by human peripheral blood T cells is regulated by mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR)". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 280 (2): 1037–43. doi:10.1074/jbc.M405204200. PMID 15522880.

- ^ Cang C, Zhou Y, Navarro B, Seo YJ, Aranda K, Shi L, Battaglia-Hsu S, Nissim I, Clapham DE, Ren D (February 2013). "mTOR regulates lysosomal ATP-sensitive two-pore Na(+) channels to adapt to metabolic state". Cell. 152 (4): 778–90. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2013.01.023. PMC 3908667. PMID 23394946.

- ^ Wu S, Mikhailov A, Kallo-Hosein H, Hara K, Yonezawa K, Avruch J (January 2002). "Characterization of ubiquilin 1, an mTOR-interacting protein". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Cell Research. 1542 (1–3): 41–56. doi:10.1016/S0167-4889(01)00164-1. PMID 11853878.

추가 정보

- Saxton RA, Sabatini DM (March 2017). "mTOR Signaling in Growth, Metabolism, and Disease". Cell. 168 (6): 960–976. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2017.02.004. PMC 5394987. PMID 28283069.