카페인

Caffeine | |

| |

| 임상자료 | |

|---|---|

| 발음 | /k æˈ파이 ːn, ˈk æ파이 ːn/ |

| 기타이름 | 과라닌 메틸테오브로민 1,3,7-트리메틸크산틴 7-메틸테오필린[1] 테인 |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | 모노그래프 |

| 임신 카테고리 |

|

| 의존성 법적 책임 | 물리적: 저중도[2][3][4][5] 심리적: 낮음[6] |

| 중독 법적 책임 | 없음-낮음[2][3][4][5] |

| 경로 행정부. | 입으로, 염증, 관장, 직장, 정맥주사 |

| 드럭 클래스 | 흥분제 아데노신저릭 우제로학 파라심패토믹 콜린에스테라아제억제제 포스포다이에스테라아제억제제 이뇨제 |

| ATC코드 | |

| 법적지위 | |

| 법적지위 |

|

| 약동학적 자료 | |

| 생체이용률 | 99%[7] |

| 단백질결합 | 25–36%[8] |

| 신진대사 | 기본: CYP1A2[8] 부전공: CYP2E1,[8] CYP3A4,[8] CYP2C8,[8]CYP2C9[8] |

| 대사산물 | 파라잔틴 (84%) 테오브로민 (12%) 테오필린(4%) |

| 동작개시 | 45분-1시간[7][9] |

| 제거 반감기 | 성인: 3-7시간[8] 유아(만기): 8시간[8] 유아(미숙기) : 100시간[8] |

| 조치기간 | 3~4시간[7] |

| 배설 | 소변(100%) |

| 식별자 | |

| |

| CAS 번호 | |

| 펍켐 CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| 드럭뱅크 | |

| 켐스파이더 | |

| 유니아이 | |

| 케그 | |

| ChEBI | |

| 쳄블 | |

| PDB 리간드 | |

| CompTox 대시보드 (EPA) | |

| ECHA 인포카드 | 100.000.329 |

| 화학 및 물리 데이터 | |

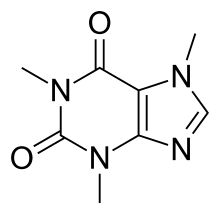

| 공식 | C8H10N4O2 |

| 어금니 질량 | 194.194g·mol |

| 3D 모델(JSMO) | |

| 밀도 | 1.23g/cm3 |

| 융점 | 235~238°C(455~460°F)([10][11]무수) |

| |

| |

| 자료페이지 | |

| 카페인 (자료 페이지) | |

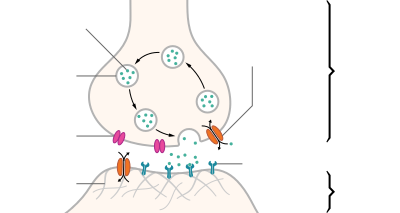

카페인은 메틸잔틴 부류의 중추신경계 자극제입니다.[12]주로 오락적으로 사용되며, 각성 촉진제(wakefulness promoter)로 사용되거나 경계심과 주의력을 높이기 위한 가벼운 인지력 향상제로 사용됩니다.[13][14]카페인은 아데노신이 아데노신 A1 수용체에 결합하는 것을 막음으로써 작용하는데, 이것은 신경 전달 물질인 아세틸콜린의 방출을 강화시킵니다.[15]카페인은 아데노신과 비슷한 3차원 구조를 가지고 있어 수용체를 결합시키고 차단할 수 있습니다.[16]카페인은 또한 포스포다이에스테라제의 비선택적 억제를 통해 순환 AMP 수치를 증가시킵니다.[17]

카페인은 쓴 흰색의 결정성 퓨린, 메틸잔틴 알칼로이드이며, 디옥시리보핵산(DNA)과 리보핵산(RNA)의 아데닌과 구아닌 염기와 화학적으로 관련이 있습니다.그것은 아프리카, 동아시아, 남아메리카가 원산지인 다수의 식물의 씨앗, 과일, 견과류 또는 잎에서 발견되며,[18] 꿀벌과 같은 선별된 동물의 섭취를 장려할 [19]뿐만 아니라 근처 씨앗의 발아를 방지하여 초식동물과 경쟁으로부터 그들을 보호하는 데 도움을 줍니다.[20]카페인의 가장 잘 알려진 공급원은 커피 식물의 씨앗인 원두입니다.사람들은 졸음을 완화하거나 예방하고 인지 능력을 향상시키기 위해 카페인이 함유된 음료를 마실지도 모릅니다.이 음료들을 만들기 위해, 카페인은 식물 제품을 물에 담그는 것으로 추출되는데, 이 과정을 인퓨전이라고 합니다.커피, 차, 콜라와 같은 카페인 함유 음료는 전세계적으로 많은 양이 소비되고 있습니다.2020년에는 전 세계적으로 거의 1천만 톤의 커피 원두가 소비되었습니다.[21]카페인은 세계에서 가장 널리 섭취되는 정신 작용 약물입니다.[22][23]대부분의 다른 정신 작용 물질들과는 달리, 카페인은 세계의 거의 모든 지역에서 대체로 규제되지 않고 합법적으로 남아있습니다.카페인은 또한 대부분의 문화권에서 사회적으로 허용되는 것으로 보여지며 심지어 다른 문화권에서도 권장되기 때문에 이상치입니다.

카페인은 건강에 긍정적인 영향과 부정적인 영향을 모두 가지고 있습니다.미숙아 호흡장애와 미숙아 무호흡증을 치료하고 예방할 수 있습니다.카페인 시트르산염은 WHO 필수 의약품 모델 리스트에 올라 있습니다.[24]파킨슨병을 [25]포함한 몇몇 질병들에 대한 적당한 보호 효과를 줄 수도 있습니다.[26]카페인을 섭취하면 수면장애나 불안감을 느끼는 사람도 있지만,[27] 거의 방해받지 않는 사람도 있습니다.임신 중 위험이 있다는 증거는 모호합니다. 일부 당국은 임신한 여성에게 카페인을 하루에 커피 두 잔 또는 그 이하의 양으로 제한할 것을 권고합니다.[28][29]카페인은 매일 반복적으로 섭취한 후 개인이 카페인 사용을 중단할 때 졸음, 두통, 과민성과 같은 금단 증상과 관련된 가벼운 형태의 약물 의존을 일으킬 수 있습니다.[2][4][6]혈압 및 심박수 증가, 소변 배출 증가 등의 자율적인 효과에 대한 내성은 만성적인 사용에 따라 발생합니다(즉, 이러한 증상은 지속적인 사용에 따라 덜 두드러지거나 발생하지 않습니다).[30]

카페인은 미국 식품의약국에 의해 일반적으로 안전하다고 인정되는 것으로 분류됩니다.성인의 경우 하루에 10그램 이상의 독성 용량이 일반적인 하루 500밀리그램 미만의 용량보다 훨씬 높습니다.[31]유럽 식품 안전청은 하루 최대 400mg의 카페인(하루 약 5.7mg/kg의 체질량)이 비임신 성인의 안전에 대한 우려를 제기하지 않는 반면, 임신 및 수유부의 하루 최대 200mg의 카페인 섭취는 태아 또는 모유 수유를 받은 유아의 안전에 대한 우려를 제기하지 않는다고 보고했습니다.[32]커피 한 잔에는 어떤 "콩" (씨앗)을 사용하는지, 어떻게 볶는지, 그리고 어떻게 준비되는지에 따라 80–175 mg의 카페인이 들어 있습니다 (예:[33] 드립, 퍼콜레이션, 또는 에스프레소).따라서 독성 용량에 도달하기 위해서는 보통 커피 50-100잔 정도가 필요합니다.하지만, 식이 보충제로 이용할 수 있는 순수 분말 카페인은 테이블스푼 크기만큼 치명적일 수 있습니다.

사용하다

의료의

카페인은 미숙아의 기관지폐이형성 예방과[34] 치료에[35] 모두 사용됩니다.그것은 치료하는[36] 동안 체중 증가를 개선하고 언어와 인지 지연을 줄일 뿐만 아니라 뇌성마비의 발생을 줄일 수 있습니다.[37][38]반면, 미묘한 장기 부작용도 발생할 수 있습니다.[39]

카페인은 미숙아 무호흡증의 1차 치료제로 사용되지만 예방은 아닙니다.[40][41][42]또한 기립성 저혈압 치료에도 사용됩니다.[43][42][44]

어떤 사람들은 천식을 치료하기 위해 커피나 차와 같은 카페인이 함유된 음료를 사용합니다.[45]이 관행을 뒷받침하는 증거는 빈약합니다.[45]저용량의 카페인은 천식 환자의 기도 기능을 향상시켜 최대 4시간 동안 강제 호기량(FEV1)을 5%에서 18%까지 증가시키는 것으로 보입니다.[46]

파라세타몰이나 이부프로펜과 같은 일반적으로 처방되는 진통제에 카페인(100-130 mg)을 첨가하면 통증 완화를 달성하는 사람들의 비율이 약간 향상됩니다.[47]

복부 수술 후 카페인 섭취는 정상적인 장 기능 회복 시간을 단축시키고 입원 기간을 단축시킵니다.[48]

카페인은 과거에 ADHD의 2차 치료제로 사용되었습니다.그것은 메틸페니데이트나 암페타민보다는 덜 효과적이지만 ADHD 어린이들에게는 위약보다는 더 효과적인 것으로 여겨집니다.[49][50]ADHD를 앓고 있는 어린이, 청소년, 성인들은 카페인을 섭취할 가능성이 더 높으며, 아마도 자가 치료의 한 형태일 것입니다.[50][51]

성능향상

인지능력

카페인은 피로와 졸음을 줄일 수 있는 중추신경계 자극제입니다.[12]정상 용량에서 카페인은 학습과 기억력에 다양한 영향을 미치지만, 일반적으로 반응 시간, 각성, 집중력, 운동 조정력을 향상시킵니다.[52][53]이러한 효과를 내기 위해 필요한 카페인의 양은 신체 크기와 내성의 정도에 따라 사람마다 다릅니다.[52]원하는 효과는 소비 후 약 1시간 후에 발생하며, 보통 용량의 원하는 효과는 일반적으로 약 서너 시간 후에 가라앉습니다.[7]

카페인은 수면을 지연시키거나 예방할 수 있으며 수면부족 기간 동안 업무수행능력을 향상시킵니다.[54]카페인을 사용하는 교대 근무자들은 졸음으로 인해 발생할 수 있는 실수를 덜 합니다.[55]

카페인은 용량에 따라 피로한 사람과 정상인 모두의 경계심을 증가시킵니다.[56]

2014년의 체계적인 검토와 메타 분석에 따르면 카페인과 L-테아닌의 동시 사용은 경계심, 주의력 및 작업 전환을 촉진하는 상승적인 정신 활동적 효과를 가지고 있습니다.[57] 이러한 효과는 투여 후 첫 한 시간 동안 가장 두드러집니다.[57]

물리적 성능

카페인은 인간에게 입증된 에르고겐 보조제입니다.[58]카페인은 유산소성(특히 지구력 스포츠)과 무산소성 상태에서 운동 능력을 향상시킵니다.[58]적당한 양의 카페인(약 5mg/kg[58])은 스프린트 성능,[59] 사이클링 및 러닝 타임 트라이얼 성능,[58] 내구성(즉, 근육 피로 및 중심 피로의 시작을 지연),[58][60][61] 사이클링 동력 출력을 향상시킬 수 있습니다.[58]카페인은 성인의 기초 대사율을 증가시킵니다.[62][63][64]유산소 운동 전 카페인 섭취는 특히 체력이 낮은 사람들에게 지방 산화를 증가시킵니다.[65]

카페인은 근력과 힘을 향상시키고 [66]근지구력을 향상시킬 수 있습니다.[67]카페인은 혐기성 테스트에서도 성능을 향상시킵니다.[68]지속적인 부하 운동을 하기 전 카페인 섭취는 지각된 힘을 줄이는 것과 관련이 있습니다.운동과 탈진 운동 중에는 이러한 효과가 나타나지 않지만 성능은 크게 향상됩니다.이것은 카페인이 지각된 운동을 줄이는 것과 일치하는데, 왜냐하면 운동과 탈진은 같은 피로 지점에서 끝나야 하기 때문입니다.[69]카페인은 또한 출력을 향상시키고 유산소 시간 시험에서 완료까지 시간을 단축시키는데,[70] 이는 더 긴 지속 시간 운동과 관련된 긍정적인 효과입니다.[71]

특정집단

어른들

건강한 성인들의 일반인들에게, 캐나다 보건국은 하루 섭취량이 400 mg 이하여야 한다고 권고하고 있습니다.[72]이 한계는 카페인 독성학에 대한 2017년 체계적인 검토에 의해 안전한 것으로 밝혀졌습니다.[73]

아이들.

건강한 어린이의 경우, 400 mg 이하의 적당한 카페인 섭취는 "적당하고 전형적으로 무해한" 효과를 가져옵니다.[74][75]생후 6개월부터 유아는 성인과 같은 속도로 카페인을 대사할 수 있습니다.[76]카페인 함량이 400mg 이상일 경우 생리적, 심리적, 행동적 해를 입힐 수 있으며, 특히 정신과나 심장 질환이 있는 어린이의 경우 더욱 그렇습니다.[74]커피가 아이의 성장을 방해한다는 증거는 없습니다.[77]미국 소아과 학회는 카페인 섭취가 어린이와 청소년에게 적절하지 않으므로 피해야 한다고 권고하고 있습니다.[78]본 권고안은 1994년부터 2011년까지 45개의 출판물에 대한 검토와 함께 2011년에 발표된 미국 소아과 학회의 임상 보고서를 기반으로 하며, 다양한 이해 관계자(소아과 의사, 영양 관련 위원회, 캐나다 소아과 학회, 질병통제예방센터, 식품의약청, 스포츠 의학)의 의견을 포함합니다.전미 고등학교 협회(National Federations of High School Associations)의 아이신 & 피트니스(icine & Fitness Committee).[78]캐나다 보건부는 12세 이하 어린이의 경우 체중 1kg당 카페인 최대 섭취량을 2.5mg 이하로 권장하고 있습니다.어린이의 평균 체중을 기준으로 할 때, 이는 다음과 같은 연령 기준 섭취 제한을 의미합니다.[72]

| 연령대 | 하루 최대 카페인 권장 섭취량 |

|---|---|

| 4–6 | 45 mg (일반적인 카페인이 함유된 청량 음료 355 ml (12 fl. oz) 보다 slightly) |

| 7–9 | 62.5 mg |

| 10–12 | 85mg (약)커피 1⁄2컵) |

청소년

캐나다 보건은 불충분한 데이터 때문에 청소년을 위한 조언을 개발하지 못했습니다.그러나, 그들은 이 연령대의 하루 카페인 섭취량이 체중당 2.5 mg/kg 이하일 것을 제안합니다.성인 카페인 최대 용량이 가벼운 청소년이나 아직 성장기인 어린 청소년에게는 적절하지 않을 수 있기 때문입니다.매일 2.5 mg/kg의 체중은 대다수의 청소년 카페인 소비자들에게 건강에 악영향을 끼치지 않을 것입니다.이것은 나이가 많고 몸무게가 많이 나가는 청소년들이 부작용을 겪지 않고 성인 카페인을 섭취할 수 있기 때문에 보수적인 제안입니다.[72]

임신 및 모유수유

임신, 특히 임신 3기에는 카페인의 대사가 감소하고, 임신 중 카페인의 반감기는 최대 15시간까지 증가할 수 있습니다(비임신 성인의 경우 2.5~4.5시간에 비해).[79]임신과 모유 수유에 대한 카페인의 영향에 관한 현재의 증거는 확정적이지 않습니다.[28]임신 중 카페인 사용과 태아 또는 신생아에 미치는 영향에 대한 1차 및 2차 조언은 제한적입니다.[28]

영국 식품 표준청은 임신한 여성들이 조심스럽게 카페인 섭취를 하루에 200mg 이하로 제한할 것을 권고했습니다. 이는 인스턴트 커피 두 잔 또는 신선한 커피 한 잔 반에서 두 잔과 맞먹는 양입니다.[80]미국 산부인과 학회는 2010년에 임신한 여성들이 카페인을 하루에 200 mg까지 섭취해도 안전하다는 결론을 내렸습니다.[29]모유 수유를 하거나, 임신을 했거나, 임신을 했을 수도 있는 여성의 경우, 캐나다 보건부는 하루 최대 카페인 섭취량이 300mg 이하이거나, 커피를 8온즈(237mL) 두 잔을 조금 넘는 것을 권장합니다.[72]2017년 카페인 독성학에 대한 체계적인 검토는 임산부의 카페인 섭취량이 일반적으로 생식 또는 발달에 악영향을 미치지 않는다는 증거를 발견했습니다.[73]

과학 문헌에는 임신 중 카페인 사용에 대해 상반된 보고가 있습니다.[81]2011년 리뷰에 따르면 임신 중 카페인은 적당량에서 많은 양을 섭취하더라도 선천적 기형, 유산 또는 성장 지체의 위험을 증가시키지 않는 것으로 나타났습니다.[82]그러나 다른 리뷰들은 임신한 여성들의 카페인 섭취가 더 높은 저체중아 출산 위험과 관련이 있을 수 있고 임신 [83]손실 위험이 더 높을 수 있다는 증거가 있다고 결론 내렸습니다.[84]관찰 연구의 결과를 분석한 체계적인 검토는 임신하기 전에 많은 양의 카페인(하루에 300mg 이상)을 섭취하는 여성이 임신 손실을 경험할 위험이 더 높을 수 있음을 시사합니다.[85]

역효과

물리적.

커피와 다른 카페인 음료에 들어있는 카페인은 위장 운동과 위산 분비에 영향을 미칠 수 있습니다.[86][87][88]폐경기 여성의 경우 카페인을 많이 섭취하면 뼈 손실이 가속화될 수 있습니다.[89][90]

카페인을 다량(최소 250~300mg, 커피 2~3잔 또는 차 5~8잔에서 발견되는 양과 동일)으로 급성 섭취하면 며칠 또는 몇 주 동안 카페인을 섭취하지 못한 사람들의 소변 배출이 단기적으로 촉진됩니다.[91]이러한 증가는 이뇨증(물 배설의 증가)과 이뇨증(식염수 배설의 증가)으로 인한 것이며, 근위부 튜브 아데노신 수용체 차단을 통해 매개됩니다.[92]소변량의 급격한 증가는 탈수의 위험을 증가시킬 수 있습니다.그러나 만성적인 카페인 사용자는 이러한 효과에 대해 내성이 생기고 소변 배출이 증가하지 않습니다.[93][94][95]

심리학적

정신과적 진단을 보장할 만큼 충분히 심각하지 않은 카페인 섭취로 인한 사소한 원치 않는 증상은 흔하며 가벼운 불안, 초조함, 불면증, 수면 지연 증가 및 조정력 감소를 포함합니다.[52][96]카페인은 불안장애에 부정적인 영향을 미칠 수 있습니다.[97]2011년 문헌고찰에 따르면 카페인 사용은 파킨슨병을 앓고 있는 사람들에게 불안과 공황장애를 유발할 수 있다고 합니다.[98]일반적으로 300mg 이상의 고용량의 카페인은 불안감을 유발하거나 악화시킬 수 있습니다.[99]어떤 사람들에게는 카페인 사용을 중단하는 것이 상당히 불안감을 줄여줄 수 있습니다.[100]

적당한 용량의 카페인은 우울증 증상 감소와 자살 위험 감소와 관련이 있습니다.[101]두 개의 리뷰는 커피와 카페인 섭취의 증가가 우울증의 위험을 감소시킬지도 모른다는 것을 나타냅니다.[102][103]

어떤 교과서들은 카페인이 가벼운 행복감을 주는 물질이라고 언급하는 반면,[104][105][106] 다른 교과서들은 카페인이 행복감을 주는 물질이 아니라고 언급합니다.[107][108]

카페인 유도 불안 장애는 물질/약물 유도 불안 장애의 DSM-5 진단의 하위 분류입니다.[109]

보강장애

중독

카페인이 중독성 장애를 초래할 수 있는지의 여부는 중독을 어떻게 정의하느냐에 달려 있습니다.어떤 상황에서도 카페인을 강박적으로 섭취하는 것은 관찰되지 않았으며, 따라서 카페인은 일반적으로 중독성이 있다고 간주되지 않습니다.[110]그러나 ICDM-9 및 ICD-10과 같은 일부 진단 모델은 보다 광범위한 진단 모델 하에서 카페인 중독의 분류를 포함합니다.[111]어떤 사람들은 특정 사용자들이 중독될 수 있고 따라서 부정적인 건강 영향이 있다는 것을 알면서도 사용을 줄일 수 없다고 말합니다.[112][113]

카페인은 강화하는 자극제가 아닌 것으로 보이며, NIDA 연구 논문에 발표된 약물 남용 책임에 대한 연구에서 사람들이 카페인보다 위약을 선호하는 등 어느 정도의 혐오감이 실제로 발생할 수 있습니다.[114]어떤 사람들은 연구가 카페인 중독의 근본적인 생화학적 메커니즘에 대한 지지를 제공하지 않는다고 말합니다.[2][115][116][117]다른 연구에서는 그것이 보상체계에 영향을 줄 수 있다고 말합니다.[118]

"카페인 중독"이 ICDM-9와 ICD-10에 추가되었습니다.그러나 카페인 중독 진단 모델이 증거에 의해 뒷받침되지 않는다는 주장과 이의 추가가 경합되었습니다.[2][3][119]미국정신의학협회의 DSM-5는 카페인 중독 진단을 포함하지 않지만 더 많은 연구를 위해 카페인 중독에 대한 기준을 제안합니다.[109][120]

의존 및 인출

금단은 일상적인 기능에 경미한 또는 임상적으로 상당한 장애를 유발할 수 있습니다.이런 현상이 발생하는 빈도는 11%로 자체 보고되고 있지만, 실험실 테스트에서는 금단현상을 신고한 사람의 절반만이 실제로 경험하고 있어 많은 의존성 주장에 의문이 제기되고 있습니다.[121]가벼운 신체적 의존과 금단 증상은 금욕 시 나타날 수 있으며, 카페인은 하루 100mg 이상이지만 이러한 증상은 하루 이상 지속될 수 있습니다.[2]심리적 의존과 관련된 일부 증상들은 금단현상 동안에도 발생할 수 있습니다.[6]카페인 금단에 대한 진단 기준은 이전에 매일 카페인을 장기간 사용할 것을 요구합니다.[122]24시간의 현저한 소비 감소 후, 이러한 증상들 중 적어도 3가지는 금단 기준을 충족시키기 위해 필요합니다: 집중하기 어려움, 우울한 기분/불쾌함, 독감과 유사한 증상, 두통, 그리고 피로.[122]또한 징후와 증상은 중요한 기능 영역을 방해해야 하며 다른 상태의 영향과 관련이 없습니다.[122]

ICD-11은 별개의 진단 범주로서 카페인 의존성을 포함하고 있으며, 이는 DSM-5가 제안한 "카페인 사용 장애"에 대한 기준 세트를 면밀히 반영합니다.[120][123]카페인 사용 장애는 부정적인 생리학적 결과에도 불구하고 카페인 섭취를 조절하지 못하는 것을 특징으로 하는 카페인에 대한 의존을 말합니다.[120][123]DSM-5를 발표한 APA는 DSM-5의 카페인 의존 진단 모델을 만들기에 충분한 증거가 있다는 것을 인정했지만, 그들은 DSM-5의 임상적 의미가 불분명하다고 지적했습니다.[124]임상적 중요성에 대한 결정적이지 않은 증거 때문에 DSM-5는 카페인 사용 장애를 "추가 연구를 위한 조건"으로 분류합니다.[120]

카페인의 영향에 대한 내성은 카페인으로 인한 혈압 상승과 주관적인 신경과민에 대해 발생합니다.사용함에 따라 효과가 더욱 두드러지는 과정인 감작은 경계심과 안녕감과 같은 긍정적인 효과에 대해 발생합니다.[121]허용오차는 매일, 정기적인 카페인 사용자와 고카페인 사용자에 따라 다릅니다.고용량의 카페인(하루에 750에서 1200 mg/일)은 일부에 대해 완전한 내성을 생성하지만 카페인의 모든 영향은 아닙니다.커피 6온스(170g) 컵 또는 12온스(340g) 2~3인분의 카페인이 함유된 청량음료와 같이 하루에 100mg/day 정도의 낮은 용량은 다른 불내증 중에서도 수면 장애를 계속 유발할 수 있습니다.비정규 카페인 사용자는 수면 장애에 대한 카페인 내성이 가장 적습니다.[125]커피를 마시는 사람들 중 일부는 원치 않는 수면 방해 효과에 내성이 생기지만, 다른 사람들은 분명히 그렇지 않습니다.[126]

기타 질병의 위험성

알츠하이머병과 치매에 대한 카페인의 신경 보호 효과는 가능하지만 그 증거는 확정적이지 않습니다.[127][128]

규칙적인 카페인 섭취는 사람들을 간경화로부터 보호해 줄 지도 모릅니다.[129]또한 이미 간질환을 가지고 있는 사람들의 간질환의 진행을 늦추고, 간섬유화의 위험을 감소시키며, 적당한 커피를 마시는 사람들의 간암에 대한 보호효과를 제공하는 것으로 밝혀졌습니다.2017년에 수행된 한 연구는 커피 섭취로 인한 카페인이 간에 미치는 영향이 음료가 어떻게 제조되는지와 관계없이 관찰된다는 것을 발견했습니다.[130]

카페인은 높은 고도에 오르기 몇 시간 전에 섭취하면 급성 산병의 심각성을 줄일 수 있습니다.[131]한 메타 분석은 카페인 섭취가 제2형 당뇨병의 위험 감소와 관련이 있다는 것을 발견했습니다.[132]규칙적인 카페인 섭취는 파킨슨병 발병 위험을 감소시키고 파킨슨병의 진행을 늦출 수 있습니다.[133][134][26]

카페인은 녹내장 환자의 안압을 증가시키지만 정상인에게는 영향을 미치지 않는 것으로 보입니다.[135]

DSM-5는 카페인에 의한 불안장애, 카페인에 의한 수면장애, 특정되지 않은 카페인 관련 장애로 구성된 다른 카페인에 의한 장애도 포함합니다.처음 두 가지 장애는 유사한 특징을 가지고 있기 때문에 "불안장애"와 "수면-깨어있는 장애"로 분류됩니다.임상적 주의가 필요한 일상적 기능의 현저한 장애 및 장애가 있지만 특정 장애에서 진단해야 할 기준을 충족하지 못하는 기타 장애는 "지정되지 않은 카페인 관련 장애"에 열거되어 있습니다.[136]

과다 복용

하루에 1-1.5 그램 (1,000–1,500 mg)의 섭취는 알려진 질환과 관련이 있습니다.[138] 카페인 중독은 보통 카페인 의존성을 신경과민, 짜증, 불안, 불면증, 두통, 그리고 카페인 사용 후 두근거림을 포함한 광범위한 불쾌한 증상들과 결합시킵니다.[139]

카페인 과다 복용은 카페인 중독으로 알려진 중추신경계 과잉 자극 상태를 야기할 수 있습니다. 카페인 중독은 카페인 섭취 중에 또는 섭취 직후에 발생하는 임상적으로 중요한 일시적인 증상입니다.[140]이 증후군은 일반적으로 카페인이 함유된 음료와 카페인 정제에서 발견되는 양(예: 한번에 400-500 mg 이상)을 훨씬 넘는 많은 양의 카페인을 섭취한 후에만 발생합니다.DSM-5에 따르면, 카페인 중독은 불안정, 신경질, 흥분, 불면증, 홍조 있는 얼굴, 이뇨증, 위장 장애, 근육 경련, 생각과 말의 횡설수설, 빈맥 또는 심장 부정맥, 페무진장의 시대와 정신 운동의 동요.[141]

국제질병분류(ICD-11)에 따르면, 카페인 섭취량이 매우 높은 경우(예: 5g 이상), 조증, 우울증, 판단력 저하, 방향감각 상실, 저해, 망상, 환각 또는 정신병, 횡문근융해증을 포함한 증상으로 카페인 중독을 초래할 수 있습니다.[140]

에너지 드링크

에너지 드링크의 높은 카페인 섭취(최소 1리터 또는 320mg의 카페인)는 고혈압, 장기간의 QT 간격 및 심장 두근거림을 포함한 단기 심혈관 부작용과 관련이 있었습니다.이러한 심혈관 부작용은 에너지 드링크의 카페인 섭취량(200 mg 미만)에서는 나타나지 않았습니다.[79]

심한 도취

2007년[update] 현재 카페인 중독에 대한 알려진 해독제나 역전제는 없습니다.가벼운 카페인 중독의 치료는 증상 완화를 지향합니다. 심한 중독은 복막 투석, 혈액 투석 또는 혈액 여과가 필요할 수 있습니다.[137][142][143]무료 혈청 카페인을 제거하기 위해 심장 정지의 위험이 임박한 경우에는 수액 요법을 사용해야 합니다.[143]

치사량

카페인 섭취로 인한 사망은 드문 것으로 보이며, 가장 일반적으로 약물 과다 복용으로 인해 발생합니다.[144]2016년에 미국의 Poison Control Centers에 3702건의 카페인 관련 노출이 보고되었으며, 이 중 846건은 의료 시설에서 치료가 필요했고, 16건은 주요 결과를 나타냈고, 사례 연구에서 여러 카페인 관련 사망자가 보고되었습니다.[144]쥐의 카페인 LD는50 킬로그램당 192 밀리그램이며, 인간의 치명적인 용량은 킬로그램당 150-200 밀리그램으로 추정됩니다([145][146]성인 70 킬로그램당 75-100 컵의 커피).킬로그램당 57밀리그램 정도의 저용량이 치명적인 경우도 있습니다.[147]많은 사망자들은 쉽게 구할 수 있는 가루 카페인 보충제의 과다 복용으로 인해 발생하고 있는데, 이는 추정 치사량이 1테이블스푼도 되지 않습니다.[148]유전자나 만성 간 질환으로 카페인 대사 능력이 손상된 사람의 치사량은 더 낮습니다.[149]2013년 카페인이 함유된 민트를 과다 복용한 간경변증 남성의 사망 사례가 보고됐습니다.[150][151]

상호작용

카페인은 CYP1A2의 기질이며, 이것과 다른 메커니즘을 통해 많은 물질과 상호작용합니다.[152]

술

DSST에 따르면 알코올은 표준화된 테스트에서 성능 저하를 유발하고 카페인은 상당한 개선을 유발합니다.[153]알코올과 카페인을 함께 섭취하면 카페인의 효과는 달라지지만 알코올 효과는 그대로 유지됩니다.[154]예를 들어, 카페인을 추가로 섭취한다고 해서 알코올의 영향이 줄어들지는 않습니다.[154]그러나 알코올을 더 섭취하면 카페인이 주는 신경과민은 줄어듭니다.[154]알코올 섭취만으로도 행동 통제의 억제적인 측면과 활동적인 측면이 모두 줄어듭니다.카페인은 행동 조절의 활성화 측면을 적대시하지만, 억제 행동 조절에는 영향을 미치지 않습니다.[155]미국인 식생활 지침에서는 알코올과 카페인을 함께 섭취하면 알코올 섭취량이 증가하고 알코올로 인한 부상 위험이 높아질 수 있으므로 알코올과 카페인을 함께 섭취하지 말 것을 권고하고 있습니다.

담배

담배를 피우면 카페인 제거율이 56%[156] 증가합니다.담배 흡연은 카페인을 분해하는 시토크롬 P4501A2 효소를 유도하는데, 이는 일반 흡연자들의 카페인 내성과 커피 섭취 증가로 이어질 수 있습니다.[157]

산아제한

피임약은 카페인의 반감기를 연장시켜 카페인 섭취에 더 많은 주의를 요구합니다.[158]

약물

카페인은 때때로 두통약과 같은 일부 약물의 효과를 증가시킵니다.[159]카페인은 일부 처방전 없이 살 수 있는 진통제의 효능을 40%[160]까지 높이기로 했습니다.

아데노신의 약리학적 효과는 카페인과 같은 다량의 메틸잔틴을 섭취하는 사람들에게서 무뎌질 수 있습니다.[161]메틸잔틴의 다른 예로는 천식이나 COPD의 증상을 완화하기 위해 처방되는 테오필린과 아미노필린이 있습니다.[162]

약리학

약력학

카페인이 없을 때 그리고 사람이 깨어있을 때 그리고 경계할 때, CNS 뉴런에는 아데노신이 거의 존재하지 않습니다.계속된 각성 상태에서, 시간이 지남에 따라 아데노신이 뉴런 시냅스에 축적되고, 차례로 특정 CNS 뉴런에서 발견되는 아데노신 수용체에 결합하고 활성화합니다; 활성화되면, 이러한 수용체는 궁극적으로 졸음을 증가시키는 세포 반응을 생성합니다.카페인을 섭취하면 아데노신 수용체에 대항하게 되는데, 다시 말해 카페인은 아데노신이 수용체와 결합하는 수용체의 위치를 막아 수용체의 활성화를 방해합니다.결과적으로 카페인은 일시적으로 졸음을 예방하거나 완화시켜 주기 때문에 경계심을 유지하거나 회복합니다.[8]

수용체 및 이온채널 표적

카페인은 아데노신 A2A 수용체의 길항제이며 녹아웃 마우스 연구는 특히 카페인의 각성 촉진 효과에 책임이 있는 A2A 수용체의 길항제를 포함하고 있습니다.[163]복측방전시영역(VLPO)에서2A A 수용체의 길항작용은 활성화 의존적으로 각성을 촉진하는 히스타민제 투사핵인 결핵모양핵으로의 억제적 GABA 신경전달을 감소시킵니다.[164]결핵균의 억제를 억제하지 못하는 것은 카페인이 각성을 촉진하는 효과를 만들어내는 하류 메커니즘입니다.[164]카페인은 다양한 효능을 가지고 있지만, 네 가지 아데노신 수용체 아형(A12A, A, A2B, A3) 모두의 길항제입니다.[8][163]인간 아데노신 수용체에 대한 카페인의 친화도(KD) 값은 A에서1 12 μM, A에서2A 2.4 μM, A에서2B 13 μM, A에서3 80 μM입니다.[163]

카페인에 의한 아데노신 수용체의 길항작용은 또한 미주신경, 혈관운동, 호흡 중추를 자극하여 호흡수를 증가시키고 심박수를 감소시키며 혈관을 수축시킵니다.[8]아데노신 수용체 길항제는 또한 자극제 효과로 카페인을 공급하는 신경전달물질 방출(예: 모노아민과 아세틸콜린)을 촉진합니다;[8][165] 아데노신은 중추신경계의 활동을 억제하는 억제적인 신경전달물질로 작용합니다.심장 두근거림은 A 수용체의1 차단으로 인해 발생합니다.[8]

카페인은 물과 지질 둘 다 용해성이기 때문에 뇌의 내부로부터 혈류를 분리하는 혈액 뇌 장벽을 쉽게 넘습니다.일단 뇌에 들어가면, 주요 작용 방식은 아데노신 수용체의 비선택적 길항제(즉, 아데노신의 효과를 감소시키는 작용제)입니다.카페인 분자는 구조적으로 아데노신과 유사하며, 활성화 없이 세포 표면의 아데노신 수용체와 결합할 수 있어 경쟁적 길항제로 작용합니다.[166]

아데노신 수용체에서의 활성 이외에도, 카페인은 이노시톨 삼인산 수용체 1 길항제이며, 라이언오딘 수용체(RYR1, RYR2, RYR3)의 전압-독립 활성화제입니다.[167]또한 이온성 글리신 수용체의 경쟁적 길항제이기도 합니다.[168]

선조체 도파민에 미치는 영향

카페인이 도파민 수용체에 직접적으로 결합하지는 않지만, 도파민 수용체와 GPCR 이성질체를 형성한 아데노신 수용체에 결합함으로써 선조체에 있는 수용체에서 도파민의 결합 활성에 영향을 미칩니다.구체적으로1, A-D1 수용체 헤테로다이머(이것은 1개의 아데노신 A1 수용체와 1개의 도파민 D 수용체를1 갖는 수용체 복합체)와 A-D2A2 수용체 헤테로다이머(이것은 2개의 아데노신 A2A 수용체와 2개의 도파민 D 수용체를2 갖는 수용체 복합체).[169][170][171][172]A-D2A2 수용체 헤테로트래머는 카페인의 주요 약리학적 표적으로 확인되었는데, 이는 주로 그것의 정신 자극 효과의 일부와 도파민성 정신 자극제와의 약리학적 상호작용을 매개하기 때문입니다.[170][171][172]

카페인은 또한 등의 선조체에서 도파민의 방출을 야기하고 핵은 (배의 선조체 내의 하부 구조)핵을 축척하지만, 핵은 축척 껍질을 축척하지 않습니다.도파민 뉴런의 축삭 말단의 A 수용체와1 글루타메이트 뉴런의 축삭 말단의 A-A12A 헤테로다이머(1개의 아데노신1 A 수용체와 1개의 아데노신2A A 수용체로 구성된 수용체 복합체)를 길항시킴으로써.[169][164]만성적인 카페인 사용 중에, 카페인에 의한 도파민 방출은 약물 내성으로 인해 핵 침강 내에서 현저하게 감소합니다.[169][164]

효소 표적

카페인은 다른 잔틴과 마찬가지로 포스포다이에스테라아제 억제제의 역할을 합니다.[173]카페인은 경쟁적인 비선택적 포스포다이에스테라아제 억제제로서 세포내 순환 AMP를 증가시키고, 단백질 키나아제 A를 활성화시키며, TNF-알파[175][176] 및 류코트리엔[177] 합성을 억제하고, 염증 및 선천 면역을 감소시킵니다.[174][177]카페인은 또한 아세틸콜린에스테라아제 효소의 중간 억제제인 콜린에르기 시스템에 영향을 줍니다.[178][179]

약동학

커피나 다른 음료에서 나오는 카페인은 섭취 후 45분 이내에 소장에 의해 흡수되고 모든 신체 조직에 분배됩니다.[181]최고 혈중 농도는 1-2시간 이내에 도달합니다.[182]이것은 1차 운동학에 의해 제거됩니다.[183]카페인은 또한 에르고타민 타르트레이트와 카페인의 좌제(편두통 완화를 위해)[184]와 클로로부탄올과 카페인의 좌제(과식증 치료를 위해)에 의해 입증되는, 직장에서 흡수될 수도 있습니다.[185]그러나, 직장 흡수는 구강 흡수보다 덜 효율적입니다: 최대 농도 (Cmax)와 흡수된 총 양 (AUC)은 둘 다 구강 양의 약 30% (즉, 1/3.5)입니다.[186]

카페인의 생물학적 반감기(몸이 1/2 용량을 제거하는 데 필요한 시간)는 임신, 다른 약물, 간 효소 기능 수준(카페인 대사에 필요한) 및 나이와 같은 요인에 따라 개인마다 매우 다양합니다.건강한 성인에서 카페인의 반감기는 3시간에서 7시간 사이입니다.[8]성인 남성 흡연자의 경우 반감기가 30~50% 감소하고, 경구피임제를 복용하는 여성의 경우 약 2배, 임신 말기에는 장기화됩니다.[126]신생아의 경우 반감기는 80시간 이상일 수 있으며, 나이와 함께 매우 빠르게 감소할 수 있으며, 6개월까지는 성인의 수치보다 작을 수 있습니다.[126]항우울제 플루복사민(Luvox)은 카페인의 제거를 90% 이상 감소시키고, 제거 반감기를 4.9시간에서 56시간으로 10배 이상 증가시킵니다.[187]

카페인은 사이토크롬 P450 산화효소 시스템에 의해 간에서 대사되는데, 특히 CYP1A2 아이소자임에 의해 3개의 디메틸잔틴으로 대사되며,[188] 각각의 카페인은 신체에 고유한 영향을 미칩니다.

- 파라잔틴(84%):지방 분해를 증가시켜 혈중 글리세롤과 유리지방산 수치를 높입니다.

- 테오브로민(12%):혈관을 확장시키고 소변량을 증가시킵니다.테오브로민은 또한 코코아 콩(초콜릿)의 주요 알칼로이드는 초콜릿입니다.

- 테오필린(4%): 기관지의 평활근을 이완시켜주며, 천식 치료에 사용됩니다.그러나 테오필린의 치료 용량은 카페인 대사로 얻은 수준보다 몇 배나 더 많습니다.[46]

1,3,7-트리메틸루르산은 카페인의 대사산물이고 [8]7-메틸잔틴은 카페인의 대사산물입니다.[189][190]상기 대사산물 각각은 추가로 대사된 후 소변으로 배설됩니다.카페인은 심각한 간 질환을 가진 사람들에게 축적되어 반감기를 증가시킬 수 있습니다.[191]

2011년 리뷰는 카페인 섭취 증가가 카페인 이화작용의 속도를 증가시키는 두 유전자의 변화와 관련이 있다는 것을 발견했습니다.두 염색체 모두에 이런 변이가 있었던 피실험자들은 다른 사람들보다 하루에 40mg의 카페인을 더 많이 섭취했습니다.[192]이것은 아마도 유전자가 습관화의 더 큰 동기에 대한 성향으로 이어진 것이 아니라, 비슷한 바람직한 효과를 얻기 위해 더 많은 섭취가 필요하기 때문인 것으로 추정됩니다.

화학

순수한 무수 카페인은 235-238°C의 녹는점을 가진 쓴 맛이 나는 흰색의 무취 분말입니다.[10][11]카페인은 상온(2g/100mL)에서는 물에 적당히 용해되지만 끓는 물(66g/100mL)에서는 매우 용해됩니다.[193]또한 에탄올(1.5g/100mL)에도 적당하게 용해됩니다.[193]양성자화를 위해서는 강한 산을 필요로 하는 약한 염기성(결합산 pK = ~0.6)입니다.카페인은 입체 중심을[195] 포함하지 않기 때문에 카이랄 분자로 분류됩니다.[196]

카페인의 잔틴 코어는 피리미딘디온과 이미다졸이라는 두 개의 융합된 고리를 포함합니다.피리미딘디온은 주로 양쪽성 이온 공명에 존재하는 두 개의 아미드 작용기를 포함하고 있으며, 질소 원자가 인접한 아미드 탄소 원자에 이중으로 결합되어 있습니다.따라서 피리미딘 이온 시스템 내에 있는 6개의 원자는 모두 sp2 혼성이고 평면입니다.이미다졸 고리에도 공명이 있습니다.따라서, 카페인의 융합된 5,6 고리핵은 총 10개의 파이 전자를 포함하고 있으며, 따라서 휴켈의 법칙에 따라 방향족입니다.[197]

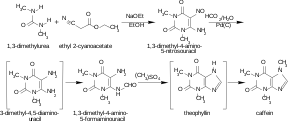

합성

카페인의 생합성은 다양한 종들 간의 융합적 진화의 한 예입니다.[202][203][204]

카페인은 실험실에서 디메틸우레아와 말론산을 시작으로 합성될 수 있습니다.[clarification needed][200][201][205]

카페인의 상업적 공급은 화학물질이 디카페인의 부산물로서 쉽게 구할 수 있기 때문에 일반적으로 합성적으로 제조되지 않습니다.[206]

디카페인

카페인과 디카페인 커피를 생산하기 위해 커피로부터 카페인을 추출하는 것은 많은 용매를 사용하여 수행될 수 있습니다.주요 방법은 다음과 같습니다.

- 물 추출: 커피콩은 물에 담급니다.카페인 이외에 많은 다른 화합물을 함유하고 있고 커피의 맛에 기여하는 그 물은 카페인을 제거하는 활성탄을 통과합니다.그리고 나서 물은 콩과 함께 다시 넣고 건조하게 증발시켜 원래의 맛을 가진 디카페인 커피를 남길 수 있습니다.커피 제조업자들은 카페인을 회수하여 청량음료나 일반 판매용 카페인 정제에 사용하기 위해 그것을 재판매합니다.[207]

- 초임계 이산화탄소 추출:초임계 이산화탄소는 카페인에 탁월한 비극성 용매이며, 다른 방법으로 사용되는 유기 용매보다 안전합니다.추출 과정은 간단합니다. CO는2 31.1°C 이상의 온도와 73 atm 이상의 압력에서 생두를 통해 강제로 배출됩니다.이러한 조건에서 CO는2 "초임계" 상태에 있습니다.그것은 콩 속 깊이 침투할 수 있는 가스와 같은 특성을 가지고 있지만 카페인의 97-99%를 용해시키는 액체와 같은 특성을 가지고 있습니다.카페인이 가득한 CO는2 그 후 카페인을 제거하기 위해 고압의 물로 뿌려집니다.카페인은 위와 같이 숯 흡착 또는 증류, 재결정 또는 역삼투압에 의해 분리될 수 있습니다.[207]

- 유기 용매에 의한 추출:에틸 아세테이트와 같은 특정 유기 용매는 이전에 사용된 염소화 및 방향족 유기 용매보다 훨씬 적은 건강 및 환경적 위험을 나타냅니다.또 다른 방법은 커피 찌꺼기로부터 얻은 트리글리세라이드 오일을 사용하는 것입니다.[207]

"디카페인" 커피는 사실 많은 경우 카페인을 함유하고 있습니다 – 일부 시판되는 디카페인 커피 제품은 상당한 수준을 함유하고 있습니다.한 연구는 디카페인 커피가 일반 커피의 경우 한 컵당 약 85mg의 카페인과 비교하여, 한 컵당 10mg의 카페인을 함유하고 있다는 것을 발견했습니다.[208]

체액에서 검출

카페인은 혈액, 혈장 또는 혈청에서 정량화되어 신생아의 치료를 감시하거나 중독 진단을 확인하거나 의학적 사망 조사를 용이하게 할 수 있습니다.혈장 카페인 수준은 보통 커피를 마시는 사람의 경우 2–10 mg/L, 무호흡 치료를 받는 신생아의 경우 12–36 mg/L, 급성 과다 복용 환자의 경우 40–400 mg/L 범위입니다.소변 카페인 농도는 경쟁 스포츠 프로그램에서 자주 측정되며, 이 프로그램에서 15mg/L를 초과하는 수치는 일반적으로 남용으로 간주됩니다.[209]

아날로그

기능이나 구조, 또는 둘 다를 가진 카페인의 특성을 모방한 몇몇 유사한 물질들이 만들어졌습니다.후자의 그룹 중에는 잔틴 DMPX와[210] 드라마민의 성분인 8-클로로테오필린이 있습니다.질소 치환 크산틴 종류의 구성원들은 종종 카페인의 잠재적인 대안으로 제안됩니다.[211][unreliable source?]아데노신 수용체 길항제 부류를 구성하는 많은 다른 잔틴 유사체들이 또한 해명되었습니다.[212]

다른 카페인 유사체들:

탄닌강수량

카페인은 시코닌, 퀴닌, 스트리크닌과 같은 다른 알칼로이드와 마찬가지로 폴리페놀과 탄닌을 침전시킵니다.이 속성은 정량화 방법으로 사용할 수 있습니다.[clarification needed][213]

자연발생

약 30종의 식물이 카페인을 함유하고 있는 것으로 알려져 있습니다.[214]일반적인 공급원은 두 재배 커피 식물인 커피 아라비카(Coffea arabica)와 커피 카네포라(Coffea canepphora)의 "콩"(씨앗), 코코아 식물인 테오브로마 카카오(Theobroma cakao), 차 식물의 잎, 그리고 콜라 견과류입니다.다른 원천으로는 야우폰 홀리, 남아메리카 홀리 예르바메이트, 아마존 홀리 구아유사의 잎과 아마존 메이플 구아라나 베리의 씨앗이 있습니다.전 세계적으로 온화한 기후는 관련 없는 카페인 함유 식물을 만들어 냈습니다.

식물에 있는 카페인은 천연 살충제의 역할을 합니다: 그것은 식물을 먹고 사는 포식자 곤충들을 마비시키고 죽일 수 있습니다.[215]커피 모종이 잎이 나고 기계적 보호가 부족할 때 높은 카페인 수치가 발견됩니다.[216]또한, 커피 묘목의 주변 토양에서 높은 카페인 수치가 발견되어 주변 커피 묘목의 종자 발아를 억제하여 카페인 수치가 가장 높은 묘목은 기존 자원의 생존 경쟁자가 적습니다.[217]카페인은 찻잎에 두 군데 저장되어 있습니다.첫째, 폴리페놀과 복합화되어 있는 세포의 진공에서.이 카페인은 아마도 초식성을 억제하기 위해 곤충의 구강으로 방출될 것입니다.두번째로, 혈관 다발 주위에 병원성 곰팡이가 들어와서 혈관 다발을 식민지화하는 것을 억제할 수 있습니다.[218]꿀에 있는 카페인은 꿀벌과 같은 꽃가루 매개자의 보상 기억력을 향상시킴으로써 꽃가루를 생산하는 식물의 번식 성공을 향상시킬 수 있습니다.[20]

카페인을 함유한 다양한 식물로부터 만들어진 음료를 섭취하는 것의 효과에 있어서 다른 인식은 이러한 음료들이 심장 자극제 테오필린과 테오브로민을 포함한 다른 메틸잔틴 알칼로이드의 다양한 혼합물을 포함한다는 사실에 의해 설명될 수 있습니다.그리고 카페인과 불용성 복합체를 형성할 수 있는 폴리페놀.[219]

상품들

| 제품. | 서빙사이즈 | 1회 제공 당 카페인(mg) | 카페인(mg/L) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 카페인정(정규강도) | 1정 | 100 | — |

| 카페인 정제(추가 강도) | 1정 | 200 | — |

| 엑세드린정 | 1정 | 65 | — |

| 허쉬 스페셜 다크 (카카오 함량 45%) | 1 bar (43 g 또는 1.5 oz) | 31 | — |

| 허쉬 밀크 초콜릿 (카카오 함량 11%) | 1 bar (43 g 또는 1.5 oz) | 10 | — |

| 퍼콜레이티드 커피. | 207mL (7.0US floz) | 80–135 | 386–652 |

| 드립커피 | 207mL (7.0US floz) | 115–175 | 555–845 |

| 커피 디카페인 | 207mL (7.0US floz) | 5–15 | 24–72 |

| 커피,에스프레소 | 44–60mL (1.5–2.0US 플로즈) | 100 | 1,691–2,254 |

| 차(검정색, 녹색 및 기타 유형)를 3분 동안 담급니다. | 177mL (6.0US floz) | 22–74[223][224] | 124–418 |

| 과야키예르바메이트 (느슨한 잎) | 6g(0.21oz) | 85[225] | 약 358 |

| 코카콜라 | 355mL (12.0US 플로즈) | 34 | 96 |

| 마운틴듀 | 355mL (12.0US 플로즈) | 54 | 154 |

| 펩시 제로 슈가 | 355mL (12.0US 플로즈) | 69 | 194 |

| 과라나 남극 | 350mL (12US floz) | 30 | 100 |

| 졸트콜라 | 695mL (23.5US 플로즈) | 280 | 403 |

| 레드불 | 250 mL (8.5US floz) | 80 | 320 |

| 커피맛우유음료 | 300-600mL (10-20US 플로즈) | 33–197[226] | 66–354[226] |

카페인이 함유된 제품에는 커피, 차, 청량 음료(colas), 에너지 드링크, 기타 음료, 초콜릿,[227] 카페인 정제, 기타 경구 제품 및 흡입 제품이 포함됩니다.미국의 2020년 연구에 따르면, 커피는 중년 성인들의 카페인 섭취의 주요 원천인 반면, 청량음료와 차는 청소년들의 주요 원천입니다.[79]에너지 드링크는 성인에 비해 청소년에서 카페인 공급원으로 더 흔하게 소비됩니다.[79]

음료

커피.

세계 카페인의 주요 공급원은 커피가 만들어지는 커피 "콩" (커피 식물의 씨앗)입니다.커피에 함유된 카페인 함량은 커피콩의 종류와 사용되는 제조 방법에 따라 매우 다양합니다;[228] 심지어 주어진 덤불 안에 있는 콩도 농도의 차이를 보일 수 있습니다.일반적으로 커피 1회 제공량은 80~100mg, 아라비카 품종 에스프레소 1회 제공량은 30mg, 드립 커피 1잔 제공량은 약 100~125mg입니다.[229][230]아라비카 커피는 일반적으로 로부스타 품종의 카페인의 절반을 함유하고 있습니다.[228]일반적으로, 로스팅 과정이 콩의 카페인 함량을 소량 감소시키기 때문에 다크 로스팅 커피는 가벼운 로스팅보다 카페인 함량이 매우 약간 적습니다.[229][230]

차

차는 건조한 무게로 커피보다 카페인을 더 많이 함유하고 있습니다.그러나 일반적인 1인분은 동등한 커피 1인분에 비해 제품 사용량이 적기 때문에 훨씬 적은 양을 함유하고 있습니다.또한 카페인 함량에 기여하는 것은 성장 조건, 가공 기술, 그리고 다른 변수들입니다.따라서, 차에는 다양한 양의 카페인이 들어있습니다.[231]

차는 적은 양의 테오브로민을 함유하고 있고 커피보다 약간 높은 수준의 테오필린을 함유하고 있습니다.조제와 다른 많은 요소들은 차에 상당한 영향을 끼치는데, 색상은 카페인 함량을 나타내는 매우 빈약한 지표입니다.예를 들어 옅은 일본 녹차인 교쿠로와 같은 차들은 아주 적은 양의 라팡수청과 같은 훨씬 더 진한 차들보다 훨씬 더 많은 카페인을 함유하고 있습니다.[231]

청량음료 및 에너지 드링크

카페인은 원래 콜라 견과류로 제조된 콜라와 같은 청량 음료의 일반적인 성분이기도 합니다.탄산음료는 일반적으로 12온스(350mL) 당 0에서 55밀리그램의 카페인을 함유하고 있습니다.[232]대조적으로, 레드불과 같은 에너지 드링크는 1인분 당 카페인 80밀리그램부터 시작할 수 있습니다.이 음료들에 있는 카페인은 사용된 성분에서 유래하거나 디카페인 제품 또는 화학 합성에서 유래된 첨가물입니다.에너지 드링크의 주요 성분인 과라나는 자연적으로 발생하는 느리게 방출되는 부형제에 소량의 테오브로민과 테오필린과 함께 다량의 카페인을 함유하고 있습니다.[233]

기타음료

- 메이트는 남미의 많은 지역에서 인기있는 음료입니다.준비물은 남미산 홀리바메이트의 잎으로 박을 채우고, 잎 위에 뜨겁지만 끓지 않는 물을 붓고, 예바 잎이 아닌 액체만 뽑아내도록 거름 역할을 하는 봄빌라(bombilla)를 빨대로 마시는 것으로 구성됩니다.[234]

- 과라나(Guarana)는 브라질에서 유래한 과라나 열매의 씨앗으로 만든 청량 음료입니다.

- 에콰도르 홀리트리인 일렉스 구아유사의 잎을 끓는 물에 넣어 구아유사 차를 만듭니다.[235]

- 야우폰 홀리나무인 일렉스 토미토리아의 잎을 끓는 물에 넣어 야우폰차를 만듭니다.

- 상업적으로 준비된 커피 맛 우유 음료는 호주에서 인기가 많습니다.[236]오크사의 아이스 커피와 파머스 유니온 아이스 커피가 그 예입니다.이 음료들에 들어있는 카페인의 양은 매우 다양합니다.카페인 농도는 제조사의 주장과 크게 다를 수 있습니다.[226]

초콜렛

코코아 콩에서 파생된 초콜릿은 적은 양의 카페인을 함유하고 있습니다.초콜릿의 약한 자극 효과는 카페인뿐만 아니라 테오브로민과 테오필린의 조합 때문일지도 모릅니다.[237]일반적으로 28그램짜리 밀크 초콜릿 바에는 카페인이 디카페인 커피 한 잔만큼 들어있습니다.무게로 볼 때, 다크 초콜릿은 커피에 비해 카페인 함량이 1에서 2배입니다: 100g 당 80에서 160mg입니다.90%와 같은 더 높은 비율의 코코아는 대략 100g 당 200mg에 달하며 따라서 100g 85% 코코아 초콜릿 바에는 약 195mg의 카페인이 들어 있습니다.[221]

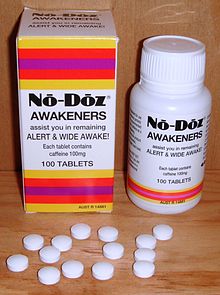

정제

정제는 커피, 차, 그리고 다른 카페인이 함유된 음료들에 비해 편리함, 알려진 복용량, 그리고 설탕, 산, 그리고 액체의 동반 섭취 방지를 포함한 여러 이점들을 제공합니다.이 형태로 카페인을 사용하는 것은 정신적인 경계심을 향상시킨다고 합니다.[238]이 태블릿들은 시험을 위해 공부하는 학생들과 장시간 일하거나 운전하는 사람들이 흔히 사용합니다.[239]

기타구강용품

한 미국 회사는 경구 용해 가능한 카페인 스트립을 판매하고 있습니다.[240]또 다른 섭취 경로는 카페인이 함유된 립밤인 스파즈스틱입니다.[241]Alert Energy Caffein Gum은 2013년 미국에서 도입되었으나 식품에 첨가된 카페인의 건강 영향에 대한 FDA의 조사 발표 이후 자발적으로 철회되었습니다.[242]

흡입제

전자담배와 유사하게 카페인 흡입기는 전자담배를 통해 카페인 또는 과라나와 같은 자극제를 전달하는 데 사용될 수 있습니다.[243]2012년, FDA는 흡입기를 판매하는 회사 중 한 곳에 경고 편지를 보내 흡입된 카페인에 대한 안전 정보가 부족하다는 우려를 표명했습니다.[244][245]

다른 약물과의 병용

- 어떤 음료들은 알코올과 카페인을 결합하여 카페인이 든 알코올 음료를 만듭니다.카페인의 흥분제 효과는 알코올의 우울증 효과를 감추고 잠재적으로 그들의 도취 수준에 대한 사용자의 인식을 감소시킬 수 있습니다.그러한 음료는 안전상의 문제로 금지의 대상이 되어 왔습니다.특히 미국 식품의약국은 맥아주 음료에 첨가되는 카페인을 '안전하지 않은 식품 첨가물'로 분류했습니다.[246]

- 야바에는 필로폰과 카페인이 혼합되어 있습니다.

- 프로피페나존/파라세타몰/카페인과 같은 진통제는 카페인과 진통제를 결합합니다.

역사

사용의 발견 및 확산

중국의 전설에 따르면, 기원전 3,000년경에 재위한 것으로 알려진 중국의 황제 선농은 어떤 나뭇잎들이 끓는 물에 빠졌을 때 향기롭고 회복력 있는 음료가 생긴다는 것을 알아차렸을 때 무심코 차를 발견했다고 합니다.[247]차를 주제로 한 유명한 초기 작품인 루위의 차징에도 선농이 언급되어 있습니다.[248]

커피를 마시거나 커피 식물에 대해 알고 있다는 믿을 만한 최초의 증거는 15세기 중반에 아라비아 남부에 있는 예멘의 수피 수도원에서 나타납니다.[249]모카에서 커피는 이집트와 북아프리카로 퍼져나갔고, 16세기에는 중동, 페르시아, 터키의 나머지 지역에까지 도달했습니다.중동에서 커피를 마시는 것은 이탈리아로, 그 다음에는 유럽의 나머지 지역으로 퍼져 나갔고, 커피 식물은 네덜란드인들에 의해 동인도 제도와 아메리카 대륙으로 옮겨졌습니다.[250]

콜라 견과류의 사용은 고대에서 유래된 것으로 보입니다.그것은 많은 서아프리카 문화권에서, 사적인 환경과 사회적인 환경에서, 활력을 되찾고 배고픔을 완화하기 위해 씹습니다.[citation needed]

코코아 콩의 사용에 대한 최초의 증거는 기원전 600년의 고대 마야의 항아리에서 발견된 잔여물에서 비롯됩니다.또한 초콜릿은 종종 바닐라, 칠레 후추, 아키오테로 맛을 낸, 조콜라틀이라고 불리는 쓰고 매운 음료에 소비되었습니다.조콜라틀은 피로와 싸우는 것으로 믿었는데, 아마도 테오브로민과 카페인 함량에 기인한 것으로 보입니다.초콜릿은 콜럼버스 이전의 메소아메리카 전역에서 중요한 사치품이었고, 코코아 콩은 종종 화폐로 사용되었습니다.[251]

소콜라틀은 스페인 사람들에 의해 유럽에 소개되었고, 1700년에 인기있는 음료가 되었습니다.스페인 사람들은 서인도[252] 제도와 필리핀에도 카카오 나무를 들여왔습니다.[253]

야우폰 홀리(일렉스 토미토리아)의 잎과 줄기는 아메리카 원주민들이 asi 또는 "블랙 드링크"라고 불리는 차를 끓이는 데 사용되었습니다.[254]고고학자들은 고대까지 이러한 용도를 사용했다는 증거를 발견했는데,[255] 아마도 후기 고대 시대의 것으로 추정됩니다.[254]

화학물질 동정, 격리, 합성

1819년 독일의 화학자 프리들립 페르디난트 룽게는 처음으로 비교적 순수한 카페인을 분리했습니다. 그는 그것을 "카페베이스"(커피에 존재하는 염기)라고 불렀습니다.[256]룽게에 따르면, 그는 요한 볼프강 폰 괴테의 명령에 따라 이 일을 저질렀다고 합니다.[a][258]1821년, 카페인은 프랑스 화학자 피에르 장 로비케(Pierre Jean Robiquet)와 또 다른 프랑스 화학자 피에르 요제프 펠레티에(Pierre-Joseph Pelletier)와 요제프 비에나이메 카벤투(Joseph Bienaimé Caventou)에 의해 분리되었다고 스웨덴 화학자 욘스 제이콥 베르젤리우스(Jöns Jacob Berzelius)가 그의 연례 저널에서 밝혔습니다.게다가, 베르젤리우스는 프랑스 화학자들이 룽지나 서로의 연구에 대한 어떠한 지식과도 독립적으로 그들의 발견을 했다고 말했습니다.[259]그러나 베르젤리우스는 나중에 카페인 추출에 있어서 룽지의 우선순위를 인정하면서 다음과 같이 진술했습니다:[260] "그러나 이 시점에서 룽지가 동일한 방법을 명시하고 발견이 o인 로비케보다 1년 앞서 카페베이스라는 이름으로 카페인을 설명했다는 것이 언급되지 않은 채로 남아 있어서는 안 됩니다.만약 이 물질이 파리에서 열린 약사회의 회의에서 처음으로 구두 발표를 한 것으로 추정됩니다."

카페인에 관한 펠레티에의 기사는 (프랑스어로 커피를 뜻하는 단어에서 카페인(Caféine)이라는 프랑스어 형태로) 인쇄된 용어를 처음으로 사용했습니다.[261]베르젤리우스의 설명을 증명해주는 자료입니다.

카페인, 명사(여성).1821년 로비케 씨가 커피에서 발견한 결정성 물질.같은 기간 동안 – 그들이 커피에서 퀴닌을 찾는 동안 – 여러 의사들은 커피가 열을 줄이는 약이라고 생각하고, 커피가 신코나 나무와 같은 과에 속하기 때문에 – Messrs.Pelletier와 Caventou는 카페인을 얻었지만, 그들의 연구가 다른 목표를 가지고 있었고, 그들의 연구가 끝나지 않았기 때문에, 그들은 이 주제에 대한 우선순위를 Robiquet씨에게 맡겼습니다.우리는 로비케씨가 왜 약학회에 그가 읽은 커피에 대한 분석을 발표하지 않았는지 알지 못합니다.그것의 출판은 우리가 카페인을 더 많이 알리고 커피의 구성 성분에 대한 정확한 생각을 할 수 있게 해주었을 것입니다.

로비케는 순수 카페인의 특성을 처음으로 분리하고 설명한 반면, [262]펠레티어는 원소 분석을 처음으로 수행했습니다.[263]

1827년, M. Oudry는 차에서 테인을 분리했지만, [264]1838년 Mulder와[265] Carl Jobst에 의해[266] 테인이 실제로 카페인과 동일하다는 것이 증명되었습니다.

1895년, 독일의 화학자 헤르만 에밀 피셔(Hermann Emil Fischer, 1852–1919)가 처음으로 카페인을 화학 성분으로부터 합성했고, 2년 후, 그는 또한 화합물의 구조식을 유도했습니다.[267]이것은 1902년 피셔가 노벨상을 수상한 업적의 일부였습니다.[268]

역사규정

커피에 자극제 역할을 하는 화합물이 포함되어 있다는 것이 인식되었기 때문에, 처음 커피와 나중에 카페인도 때때로 규제의 대상이 되어 왔습니다.예를 들어, 16세기에 메카와 오스만 제국의 이슬람교도들은 일부 계층에게 커피를 불법으로 만들었습니다.[269][270][271]영국의 찰스 2세는 1676년에,[272][273] 프로이센의 프리드리히 2세는 1777년에,[274][275] 스웨덴에서는 1756년에서 1823년 사이에 커피가 여러 차례 금지되었습니다.

1911년, 카페인은 미국 정부가 테네시주 채터누가에서 코카콜라 시럽 40통과 20통을 압수했을 때, 가장 초기에 기록된 건강 공포 중 하나의 초점이 되었고, 그 때 음료에 든 카페인이 "건강에 해롭다"고 주장했습니다.[276]비록 대법원이 후에 미국의 코카콜라 대 코카콜라 대 코카콜라의 40배럴과 20케그의 손을 들어주었지만, "습관 형성"과 "유독한" 물질 목록에 카페인을 추가하는 두 개의 법안이 1912년에 미국 하원에 제출되었습니다.제품의 라벨에 기재되어야 합니다.[277]

사회와 문화

규정

이 섹션의 예와 관점은 주로 미국을 다루며 주제에 대한 전 세계적인 관점을 나타내지 않습니다.에 따라 이 섹션을 하거나 에서 만들 수 있습니다. (2020년 10월)( 메시지를 제거하는 및 알아보기 |

미국

미국 식품의약국(FDA)은 현재 카페인 함량이 0.02% 미만인 음료만 허용하고 있지만,[278] 건강보조식품으로 판매되는 카페인 분말은 규제되지 않고 있습니다.[279]대부분의 미리 포장된 식품의 라벨은 카페인과 같은 식품 첨가물을 포함한 성분의 목록을 비율의 내림차순으로 신고해야 하는 것이 규제 요건입니다.그러나 카페인의 의무적인 정량적 표시(예: 명시된 1회 섭취 크기당 밀리그램 카페인)에 대한 규제 조항은 없습니다.자연적으로 카페인이 함유된 여러 가지 음식 재료가 있습니다.이 재료들은 반드시 식재료 목록에 표시되어야 합니다.그러나 "식품첨가물 카페인"의 경우와 마찬가지로 카페인의 자연적 공급원인 성분을 포함하는 복합식품에서 카페인의 정량적인 양을 확인할 필요는 없습니다.커피나 초콜릿은 카페인 공급원으로 널리 인식되지만, 일부 성분(예: 과라나, 예르바마테)은 카페인 공급원으로 인식되지 않을 가능성이 높습니다.이러한 카페인의 자연적인 공급원에 대하여, 식품 라벨이 카페인의 존재를 식별하거나 식품에 존재하는 카페인의 양을 명시하도록 요구하는 규제 조항은 없습니다.[280]

소비.

카페인의 전 세계 소비량은 연간 120,[22]000톤으로 추산되어 세계에서 가장 인기 있는 정신 활성 물질입니다.이것은 매일 한 사람당 평균 1인분의 카페인이 든 음료에 해당합니다.[22]카페인의 섭취는 1997년에서 2015년 사이에 안정적으로 유지되고 있습니다.[281]커피, 차 그리고 청량음료는 가장 중요한 카페인 공급원이며 에너지 드링크는 모든 연령대에 걸쳐 전체 카페인 섭취에 거의 기여하지 않습니다.[281]

종교

최근까지 제7일재림교회는 교인들에게 "카페인 음료를 삼가달라"고 요청했지만, 세례서약에서 이를 삭제했습니다(여전히 기권을 정책으로 권고하고 있습니다).[282]이 종교들 중 일부는 사람이 의학적이지 않은, 정신 활동적인 물질을 섭취해서는 안 된다고 믿거나 중독성이 있는 물질을 섭취해서는 안 된다고 믿습니다.후기성도 예수 그리스도 교회는 카페인 음료와 관련하여 다음과 같이 말했습니다: "... 건강 관행을 설명하는 교회 계시록(Docrine and Covenants 89)에는 카페인의 사용에 대한 언급이 없습니다.교회의 건강 지침은 알코올 음료, 담배를 피거나 씹는 것, 그리고 교회 지도자들이 특별히 차와 커피를 언급하도록 가르치는 '뜨거운 음료'를 금지하고 있습니다.[283]

가우디야 바이슈나바는 카페인이 정신을 흐리게 하고 감각을 과도하게 자극한다고 믿기 때문에 카페인을 자제하기도 합니다.[284]구루 밑에서 시작하려면 적어도 1년 동안 카페인, 알코올, 니코틴 또는 다른 약물을 섭취하지 않았어야 합니다.[285]

카페인이 든 음료는 오늘날 이슬람교도들에 의해 널리 소비되고 있습니다.16세기에 몇몇 이슬람 당국들은 이슬람식단법에 따라 금지된 "음주"로 그것들을 금지하려는 시도를 했으나 실패했습니다.[286][287]

기타생물

최근에 발견된 박테리아 Pseudomonas putida CBB5는 순수한 카페인을 먹고 살 수 있고 카페인을 이산화탄소와 암모니아로 분해할 수 있습니다.[288]

카페인은 새[289], 개, 고양이에게 독성이 있고 [290]연체동물, 다양한 곤충, 거미에게 뚜렷한 악영향을 미칩니다.[291]이것은 적어도 부분적으로 화합물을 대사하는 능력이 좋지 않기 때문에 단위 중량당 주어진 용량에 대해 더 높은 수준을 야기합니다.[180]카페인은 꿀벌의 보상 기억력을 향상시키는 것으로 밝혀지기도 했습니다.[20]

조사.

카페인은 반수체 밀의 염색체를 두 배로 증가시키는데 사용되어 왔습니다.[292]

참고 항목

참고문헌

- 메모들

- ^ 1819년, 룬지는 괴테에게 벨라도나가 어떻게 동공을 팽창시켰는지 보여주기 위해 초대받았고, 룬지는 고양이를 실험대상으로 삼아 그렇게 했습니다.괴테는 이 시위에 매우 감명을 받아 다음과 같이 말했습니다.

("괴테는 내가 나폴레옹의 군대에서 구출한 남자에 대해 "흑인 스타" (즉, 흑색변, 실명)와 다른 한 명에 대한 설명에 대해 가장 만족감을 표시한 후, 그리스인이 진미로 보내준 커피 원두 한 보루를 나에게 건넸습니다.괴테는 "조사에 사용할 수도 있습니다."라고 말했습니다.그의 말이 옳았습니다. 그 직후 저는 카페인을 발견했습니다. 카페인은 질소 함량이 높기 때문에 매우 유명해졌습니다."[257]라고 말했습니다.나흐뎀 괴테 미르센 그뢰 ß테 주프리덴하이트 소 위베르 디 에르제룽 데 두르흐 쉰 바렌 슈바르첸 슈바르첸 스타르 게레테텐, 위 오흐 위베르 다스 산데레 아우게스프로첸, 위베르가베르 미르노하인 샤흐텔미트 카페보넨, 디에인 그리체임도 보르쥐글리체 게산트였습니다."Auch diese könen Siezu Ihren Untersuchungen brauchen"이라고 새그테 괴테가 말했습니다.에르하테레흐트; denn bald daraufent deckteich darindas, wegenines gro ßen Stickstofgehaltes so berühmt gewordene Coffein.

- 인용문

- ^ "Caffeine". ChemSpider. Archived from the original on 14 May 2019. Retrieved 16 November 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f Malenka RC, Nestler EJ, Hyman SE (2009). "Chapter 15: Reinforcement and Addictive Disorders". In Sydor A, Brown RY (eds.). Molecular Neuropharmacology: A Foundation for Clinical Neuroscience (2nd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. p. 375. ISBN 978-0-07-148127-4.

Long-term caffeine use can lead to mild physical dependence. A withdrawal syndrome characterized by drowsiness, irritability, and headache typically lasts no longer than a day. True compulsive use of caffeine has not been documented.

- ^ a b c Karch SB (2009). Karch's pathology of drug abuse (4th ed.). Boca Raton: CRC Press. pp. 229–230. ISBN 978-0-8493-7881-2.

The suggestion has also been made that a caffeine dependence syndrome exists ... In one controlled study, dependence was diagnosed in 16 of 99 individuals who were evaluated. The median daily caffeine consumption of this group was only 357 mg per day (Strain et al., 1994).

Since this observation was first published, caffeine addiction has been added as an official diagnosis in ICDM 9. This decision is disputed by many and is not supported by any convincing body of experimental evidence. ... All of these observations strongly suggest that caffeine does not act on the dopaminergic structures related to addiction, nor does it improve performance by alleviating any symptoms of withdrawal - ^ a b c American Psychiatric Association (2013). "Substance-Related and Addictive Disorders" (PDF). American Psychiatric Publishing. pp. 1–2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 August 2015. Retrieved 10 July 2015.

Substance use disorder in DSM-5 combines the DSM-IV categories of substance abuse and substance dependence into a single disorder measured on a continuum from mild to severe. ... Additionally, the diagnosis of dependence caused much confusion. Most people link dependence with "addiction" when in fact dependence can be a normal body response to a substance. ... DSM-5 will not include caffeine use disorder, although research shows that as little as two to three cups of coffee can trigger a withdrawal effect marked by tiredness or sleepiness. There is sufficient evidence to support this as a condition, however it is not yet clear to what extent it is a clinically significant disorder.

- ^ a b Introduction to Pharmacology (third ed.). Abingdon: CRC Press. 2007. pp. 222–223. ISBN 978-1-4200-4742-4. Archived from the original on 14 January 2023. Retrieved 25 August 2017.

- ^ a b c Juliano LM, Griffiths RR (October 2004). "A critical review of caffeine withdrawal: empirical validation of symptoms and signs, incidence, severity, and associated features". Psychopharmacology. 176 (1): 1–29. doi:10.1007/s00213-004-2000-x. PMID 15448977. S2CID 5572188.

Results: Of 49 symptom categories identified, the following 10 fulfilled validity criteria: headache, fatigue, decreased energy/ activeness, decreased alertness, drowsiness, decreased contentedness, depressed mood, difficulty concentrating, irritability, and foggy/not clearheaded. In addition, flu-like symptoms, nausea/vomiting, and muscle pain/stiffness were judged likely to represent valid symptom categories. In experimental studies, the incidence of headache was 50% and the incidence of clinically significant distress or functional impairment was 13%. Typically, onset of symptoms occurred 12–24 h after abstinence, with peak intensity at 20–51 h, and for a duration of 2–9 days.

- ^ a b c d Poleszak E, Szopa A, Wyska E, Kukuła-Koch W, Serefko A, Wośko S, Bogatko K, Wróbel A, Wlaź P (February 2016). "Caffeine augments the antidepressant-like activity of mianserin and agomelatine in forced swim and tail suspension tests in mice". Pharmacological Reports. 68 (1): 56–61. doi:10.1016/j.pharep.2015.06.138. PMID 26721352. S2CID 19471083.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p "Caffeine". DrugBank. University of Alberta. 16 September 2013. Archived from the original on 4 May 2015. Retrieved 8 August 2014.

- ^ Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Military Nutrition Research (2001). "2, Pharmacology of Caffeine". Pharmacology of Caffeine. National Academies Press (US). Archived from the original on 28 September 2021. Retrieved 15 December 2022.

- ^ a b "Caffeine". Pubchem Compound. NCBI. Retrieved 16 October 2014.

Boiling Point

178 °C (sublimes)

Melting Point

238 DEG C (ANHYD) - ^ a b "Caffeine". ChemSpider. Royal Society of Chemistry. Archived from the original on 14 May 2019. Retrieved 16 October 2014.

Experimental Melting Point:

234–236 °C Alfa Aesar

237 °C Oxford University Chemical Safety Data

238 °C LKT Labs [C0221]

237 °C Jean-Claude Bradley Open Melting Point Dataset 14937

238 °C Jean-Claude Bradley Open Melting Point Dataset 17008, 17229, 22105, 27892, 27893, 27894, 27895

235.25 °C Jean-Claude Bradley Open Melting Point Dataset 27892, 27893, 27894, 27895

236 °C Jean-Claude Bradley Open Melting Point Dataset 27892, 27893, 27894, 27895

235 °C Jean-Claude Bradley Open Melting Point Dataset 6603

234–236 °C Alfa Aesar A10431, 39214

Experimental Boiling Point:

178 °C (Sublimes) Alfa Aesar

178 °C (Sublimes) Alfa Aesar 39214 - ^ a b Nehlig A, Daval JL, Debry G (1992). "Caffeine and the central nervous system: mechanisms of action, biochemical, metabolic and psychostimulant effects". Brain Research. Brain Research Reviews. 17 (2): 139–170. doi:10.1016/0165-0173(92)90012-B. PMID 1356551. S2CID 14277779.

- ^ Camfield DA, Stough C, Farrimond J, Scholey AB (August 2014). "Acute effects of tea constituents L-theanine, caffeine, and epigallocatechin gallate on cognitive function and mood: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Nutrition Reviews. 72 (8): 507–522. doi:10.1111/nure.12120. PMID 24946991.

- ^ Wood S, Sage JR, Shuman T, Anagnostaras SG (January 2014). "Psychostimulants and cognition: a continuum of behavioral and cognitive activation". Pharmacological Reviews. 66 (1): 193–221. doi:10.1124/pr.112.007054. PMC 3880463. PMID 24344115.

- ^ Ribeiro JA, Sebastião AM (2010). "Caffeine and adenosine". Journal of Alzheimer's Disease. 20 (Suppl 1): S3-15. doi:10.3233/JAD-2010-1379. PMID 20164566.

- ^ Hillis DM, Sadava D, Hill RW, Price MV (2015). Principles of Life (2 ed.). Macmillan Learning. pp. 102–103. ISBN 978-1-4641-8652-3.

- ^ Faudone G, Arifi S, Merk D (June 2021). "The Medicinal Chemistry of Caffeine". Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 64 (11): 7156–7178. doi:10.1021/acs.jmedchem.1c00261. PMID 34019396. S2CID 235094871.

- ^ Caballero B, Finglas P, Toldra F (2015). Encyclopedia of Food and Health. Elsevier Science. p. 561. ISBN 978-0-12-384953-3. Retrieved 17 June 2018.

- ^ Myers RL (2007). The 100 Most Important Chemical Compounds: A Reference Guide. Greenwood Press. p. 55. ISBN 978-0-313-33758-1. Retrieved 17 June 2018.

- ^ a b c Wright GA, Baker DD, Palmer MJ, Stabler D, Mustard JA, Power EF, Borland AM, Stevenson PC (March 2013). "Caffeine in floral nectar enhances a pollinator's memory of reward". Science. 339 (6124): 1202–4. Bibcode:2013Sci...339.1202W. doi:10.1126/science.1228806. PMC 4521368. PMID 23471406.

- ^ "Global coffee consumption, 2020/21". Statista. Archived from the original on 3 March 2021. Retrieved 10 March 2021.

- ^ a b c Burchfield G (1997). Meredith H (ed.). "What's your poison: caffeine". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Archived from the original on 26 July 2009. Retrieved 15 January 2014.

- ^ Jamieson RW (2001). "The essence of commodification: caffeine dependencies in the early modern world". Journal of Social History. 35 (2): 269–294. doi:10.1353/jsh.2001.0125. JSTOR 3790189. PMID 18546583. S2CID 22532559.

- ^ WHO Model List of Essential Medicines (PDF) (18th ed.). World Health Organization. October 2013 [April 2013]. p. 34 [p. 38 of pdf]. Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 April 2014. Retrieved 23 December 2014.

- ^ Cano-Marquina A, Tarín JJ, Cano A (May 2013). "The impact of coffee on health". Maturitas. 75 (1): 7–21. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2013.02.002. PMID 23465359.

- ^ a b Qi H, Li S (April 2014). "Dose-response meta-analysis on coffee, tea and caffeine consumption with risk of Parkinson's disease". Geriatrics & Gerontology International. 14 (2): 430–9. doi:10.1111/ggi.12123. PMID 23879665. S2CID 42527557.

- ^ O'Callaghan F, Muurlink O, Reid N (7 December 2018). "Effects of caffeine on sleep quality and daytime functioning". Risk Management and Healthcare Policy. 11: 263–271. doi:10.2147/RMHP.S156404. PMC 6292246. PMID 30573997.

- ^ a b c Jahanfar S, Jaafar SH, et al. (Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group) (June 2015). "Effects of restricted caffeine intake by mother on fetal, neonatal and pregnancy outcomes". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (6): CD006965. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006965.pub4. PMID 26058966.

- ^ a b American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (August 2010). "ACOG CommitteeOpinion No. 462: Moderate caffeine consumption during pregnancy". Obstetrics and Gynecology. 116 (2 Pt 1): 467–8. doi:10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181eeb2a1. PMID 20664420.

- ^ Robertson D, Wade D, Workman R, Woosley RL, Oates JA (April 1981). "Tolerance to the humoral and hemodynamic effects of caffeine in man". The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 67 (4): 1111–7. doi:10.1172/JCI110124. PMC 370671. PMID 7009653.

- ^ Heckman MA, Weil J, Gonzalez de Mejia E (April 2010). "Caffeine (1, 3, 7-trimethylxanthine) in foods: a comprehensive review on consumption, functionality, safety, and regulatory matters". Journal of Food Science. 75 (3): R77–R87. doi:10.1111/j.1750-3841.2010.01561.x. PMID 20492310.

- ^ EFSA Panel on Dietetic Products, Nutrition and Allergies (2015). "Scientific Opinion on the safety of caffeine". EFSA Journal. 13 (5): 4102. doi:10.2903/j.efsa.2015.4102.

- ^ Awwad S, Issa R, Alnsour L, Albals D, Al-Momani I (December 2021). "Quantification of Caffeine and Chlorogenic Acid in Green and Roasted Coffee Samples Using HPLC-DAD and Evaluation of the Effect of Degree of Roasting on Their Levels". Molecules. 26 (24): 7502. doi:10.3390/molecules26247502. PMC 8705492. PMID 34946584.

- ^ Kugelman A, Durand M (December 2011). "A comprehensive approach to the prevention of bronchopulmonary dysplasia". Pediatric Pulmonology. 46 (12): 1153–65. doi:10.1002/ppul.21508. PMID 21815280. S2CID 28339831.

- ^ Schmidt B (2005). "Methylxanthine therapy for apnea of prematurity: evaluation of treatment benefits and risks at age 5 years in the international Caffeine for Apnea of Prematurity (CAP) trial". Biology of the Neonate. 88 (3): 208–13. doi:10.1159/000087584. PMID 16210843. S2CID 30123372.

- ^ Schmidt B, Roberts RS, Davis P, Doyle LW, Barrington KJ, Ohlsson A, Solimano A, Tin W (May 2006). "Caffeine therapy for apnea of prematurity". The New England Journal of Medicine. 354 (20): 2112–21. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa054065. PMID 16707748. S2CID 22587234. Archived from the original on 22 April 2020. Retrieved 19 September 2018.

- ^ Schmidt B, Roberts RS, Davis P, Doyle LW, Barrington KJ, Ohlsson A, Solimano A, Tin W (November 2007). "Long-term effects of caffeine therapy for apnea of prematurity". The New England Journal of Medicine. 357 (19): 1893–902. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa073679. PMID 17989382. S2CID 22983543.

- ^ Schmidt B, Anderson PJ, Doyle LW, Dewey D, Grunau RE, Asztalos EV, Davis PG, Tin W, Moddemann D, Solimano A, Ohlsson A, Barrington KJ, Roberts RS (January 2012). "Survival without disability to age 5 years after neonatal caffeine therapy for apnea of prematurity". JAMA. 307 (3): 275–82. doi:10.1001/jama.2011.2024. PMID 22253394.

- ^ Funk GD (November 2009). "Losing sleep over the caffeination of prematurity". The Journal of Physiology. 587 (Pt 22): 5299–300. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.2009.182303. PMC 2793860. PMID 19915211.

- ^ Mathew OP (May 2011). "Apnea of prematurity: pathogenesis and management strategies". Journal of Perinatology. 31 (5): 302–10. doi:10.1038/jp.2010.126. PMID 21127467.

- ^ Henderson-Smart DJ, De Paoli AG (December 2010). "Prophylactic methylxanthine for prevention of apnoea in preterm infants". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2010 (12): CD000432. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000432.pub2. PMC 7032541. PMID 21154344.

- ^ a b "Caffeine: Summary of Clinical Use". IUPHAR Guide to Pharmacology. The International Union of Basic and Clinical Pharmacology. Archived from the original on 14 February 2015. Retrieved 13 February 2015.

- ^ Gibbons CH, Schmidt P, Biaggioni I, Frazier-Mills C, Freeman R, Isaacson S, Karabin B, Kuritzky L, Lew M, Low P, Mehdirad A, Raj SR, Vernino S, Kaufmann H (August 2017). "The recommendations of a consensus panel for the screening, diagnosis, and treatment of neurogenic orthostatic hypotension and associated supine hypertension". J. Neurol. 264 (8): 1567–1582. doi:10.1007/s00415-016-8375-x. PMC 5533816. PMID 28050656.

- ^ Gupta V, Lipsitz LA (October 2007). "Orthostatic hypotension in the elderly: diagnosis and treatment". The American Journal of Medicine. 120 (10): 841–7. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2007.02.023. PMID 17904451.

- ^ a b Alfaro TM, Monteiro RA, Cunha RA, Cordeiro CR (March 2018). "Chronic coffee consumption and respiratory disease: A systematic review". The Clinical Respiratory Journal. 12 (3): 1283–1294. doi:10.1111/crj.12662. PMID 28671769. S2CID 4334842.

- ^ a b Welsh EJ, Bara A, Barley E, Cates CJ (January 2010). Welsh EJ (ed.). "Caffeine for asthma". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2010 (1): CD001112. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001112.pub2. PMC 7053252. PMID 20091514.

- ^ Derry CJ, Derry S, Moore RA (December 2014). "Caffeine as an analgesic adjuvant for acute pain in adults". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2019 (12): CD009281. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd009281.pub3. PMC 6485702. PMID 25502052.

- ^ Yang TW, Wang CC, Sung WW, Ting WC, Lin CC, Tsai MC (March 2022). "The effect of coffee/caffeine on postoperative ileus following elective colorectal surgery: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials". International Journal of Colorectal Disease. 37 (3): 623–630. doi:10.1007/s00384-021-04086-3. PMC 8885519. PMID 34993568. S2CID 245773922.

- ^ Grimes LM, Kennedy AE, Labaton RS, Hine JF, Warzak WJ (2015). "Caffeine as an Independent Variable in Behavioral Research: Trends from the Literature Specific to ADHD". Journal of Caffeine Research. 5 (3): 95–104. doi:10.1089/jcr.2014.0032.

- ^ a b Downs J, Giust J, Dunn DW (September 2017). "Considerations for ADHD in the child with epilepsy and the child with migraine". Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics. 17 (9): 861–869. doi:10.1080/14737175.2017.1360136. PMID 28749241. S2CID 29659192.

- ^ Temple JL (January 2019). "Review: Trends, Safety, and Recommendations for Caffeine Use in Children and Adolescents". Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 58 (1): 36–45. doi:10.1016/j.jaac.2018.06.030. PMID 30577937. S2CID 58539710.

- ^ a b c Bolton S, Null G (1981). "Caffeine: Psychological Effects, Use and Abuse" (PDF). Orthomolecular Psychiatry. 10 (3): 202–211. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 October 2008.

- ^ Nehlig A (2010). "Is caffeine a cognitive enhancer?" (PDF). Journal of Alzheimer's Disease. 20 (Suppl 1): S85–94. doi:10.3233/JAD-2010-091315. PMID 20182035. S2CID 17392483. Archived from the original (PDF) on 31 January 2021.

Caffeine does not usually affect performance in learning and memory tasks, although caffeine may occasionally have facilitatory or inhibitory effects on memory and learning. Caffeine facilitates learning in tasks in which information is presented passively; in tasks in which material is learned intentionally, caffeine has no effect. Caffeine facilitates performance in tasks involving working memory to a limited extent, but hinders performance in tasks that heavily depend on this, and caffeine appears to improve memory performance under suboptimal alertness. Most studies, however, found improvements in reaction time. The ingestion of caffeine does not seem to affect long-term memory. ... Its indirect action on arousal, mood and concentration contributes in large part to its cognitive enhancing properties.

- ^ Snel J, Lorist MM (2011). "Effects of caffeine on sleep and cognition". Human Sleep and Cognition Part II - Clinical and Applied Research. Progress in Brain Research. Vol. 190. pp. 105–17. doi:10.1016/B978-0-444-53817-8.00006-2. ISBN 978-0-444-53817-8. PMID 21531247.

- ^ Ker K, Edwards PJ, Felix LM, Blackhall K, Roberts I (May 2010). Ker K (ed.). "Caffeine for the prevention of injuries and errors in shift workers". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2010 (5): CD008508. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008508. PMC 4160007. PMID 20464765.

- ^ McLellan TM, Caldwell JA, Lieberman HR (December 2016). "A review of caffeine's effects on cognitive, physical and occupational performance". Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 71: 294–312. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.09.001. PMID 27612937.

- ^ a b Camfield DA, Stough C, Farrimond J, Scholey AB (August 2014). "Acute effects of tea constituents L-theanine, caffeine, and epigallocatechin gallate on cognitive function and mood: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Nutrition Reviews. 72 (8): 507–22. doi:10.1111/nure.12120. PMID 24946991. S2CID 42039737.

- ^ a b c d e f Pesta DH, Angadi SS, Burtscher M, Roberts CK (December 2013). "The effects of caffeine, nicotine, ethanol, and tetrahydrocannabinol on exercise performance". Nutrition & Metabolism. 10 (1): 71. doi:10.1186/1743-7075-10-71. PMC 3878772. PMID 24330705. 견적:

카페인에 의한 성능 증가는 혐기성 스포츠뿐만 아니라 호기성 스포츠에서도 관찰되었습니다(검토를 위해 [26,30,31] 참조).

- ^ Bishop D (December 2010). "Dietary supplements and team-sport performance". Sports Medicine. 40 (12): 995–1017. doi:10.2165/11536870-000000000-00000. PMID 21058748. S2CID 1884713.

- ^ Conger SA, Warren GL, Hardy MA, Millard-Stafford ML (February 2011). "Does caffeine added to carbohydrate provide additional ergogenic benefit for endurance?" (PDF). International Journal of Sport Nutrition and Exercise Metabolism. 21 (1): 71–84. doi:10.1123/ijsnem.21.1.71. PMID 21411838. S2CID 7109086. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 November 2020.

- ^ Liddle DG, Connor DJ (June 2013). "Nutritional supplements and ergogenic AIDS". Primary Care. 40 (2): 487–505. doi:10.1016/j.pop.2013.02.009. PMID 23668655.

Amphetamines and caffeine are stimulants that increase alertness, improve focus, decrease reaction time, and delay fatigue, allowing for an increased intensity and duration of training ...

Physiologic and performance effects

• Amphetamines increase dopamine/norepinephrine release and inhibit their reuptake, leading to central nervous system (CNS) stimulation

• Amphetamines seem to enhance athletic performance in anaerobic conditions 39 40

• Improved reaction time

• Increased muscle strength and delayed muscle fatigue

• Increased acceleration

• Increased alertness and attention to task - ^ Acheson KJ, Zahorska-Markiewicz B, Pittet P, Anantharaman K, Jéquier E (May 1980). "Caffeine and coffee: their influence on metabolic rate and substrate utilization in normal weight and obese individuals" (PDF). The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 33 (5): 989–97. doi:10.1093/ajcn/33.5.989. PMID 7369170. S2CID 4515711. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 February 2020.

- ^ Dulloo AG, Geissler CA, Horton T, Collins A, Miller DS (January 1989). "Normal caffeine consumption: influence on thermogenesis and daily energy expenditure in lean and postobese human volunteers". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 49 (1): 44–50. doi:10.1093/ajcn/49.1.44. PMID 2912010.

- ^ Koot P, Deurenberg P (1995). "Comparison of changes in energy expenditure and body temperatures after caffeine consumption". Annals of Nutrition & Metabolism. 39 (3): 135–42. doi:10.1159/000177854. PMID 7486839.

- ^ Collado-Mateo D, Lavín-Pérez AM, Merellano-Navarro E, Coso JD (November 2020). "Effect of Acute Caffeine Intake on the Fat Oxidation Rate during Exercise: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis". Nutrients. 12 (12): 3603. doi:10.3390/nu12123603. PMC 7760526. PMID 33255240.

- ^ Grgic J, Trexler ET, Lazinica B, Pedisic Z (2018). "Effects of caffeine intake on muscle strength and power: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition. 15: 11. doi:10.1186/s12970-018-0216-0. PMC 5839013. PMID 29527137.

- ^ Warren GL, Park ND, Maresca RD, McKibans KI, Millard-Stafford ML (July 2010). "Effect of caffeine ingestion on muscular strength and endurance: a meta-analysis". Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 42 (7): 1375–87. doi:10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181cabbd8. PMID 20019636.

- ^ Grgic J (March 2018). "Caffeine ingestion enhances Wingate performance: a meta-analysis" (PDF). European Journal of Sport Science. 18 (2): 219–225. doi:10.1080/17461391.2017.1394371. PMID 29087785. S2CID 3548657. Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 March 2020. Retrieved 2 December 2019.

- ^ Doherty M, Smith PM (April 2005). "Effects of caffeine ingestion on rating of perceived exertion during and after exercise: a meta-analysis". Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports. 15 (2): 69–78. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0838.2005.00445.x. PMID 15773860. S2CID 19331370.

- ^ Southward K, Rutherfurd-Markwick KJ, Ali A (August 2018). "The Effect of Acute Caffeine Ingestion on Endurance Performance: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis". Sports Medicine. 48 (8): 1913–1928. doi:10.1007/s40279-018-0939-8. PMID 29876876. S2CID 46959658.

- ^ Shen JG, Brooks MB, Cincotta J, Manjourides JD (February 2019). "Establishing a relationship between the effect of caffeine and duration of endurance athletic time trial events: A systematic review and meta-analysis". Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport. 22 (2): 232–238. doi:10.1016/j.jsams.2018.07.022. PMID 30170953.

- ^ a b c d "Caffeine in Food". Health Canada. 6 February 2012. Archived from the original on 10 August 2020. Retrieved 24 August 2020.

- ^ a b Wikoff D, Welsh BT, Henderson R, Brorby GP, Britt J, Myers E, et al. (November 2017). "Systematic review of the potential adverse effects of caffeine consumption in healthy adults, pregnant women, adolescents, and children". Food and Chemical Toxicology (Systematic review). 109 (Pt 1): 585–648. doi:10.1016/j.fct.2017.04.002. PMID 28438661.

- ^ a b Temple JL (January 2019). "Review: Trends, Safety, and Recommendations for Caffeine Use in Children and Adolescents". Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (Review). 58 (1): 36–45. doi:10.1016/j.jaac.2018.06.030. PMID 30577937.

- ^ Castellanos FX, Rapoport JL (September 2002). "Effects of caffeine on development and behavior in infancy and childhood: a review of the published literature". Food and Chemical Toxicology. 40 (9): 1235–1242. doi:10.1016/S0278-6915(02)00097-2. PMID 12204387. Archived from the original on 27 July 2020. Retrieved 2 December 2019.

- ^ Temple JL, Bernard C, Lipshultz SE, Czachor JD, Westphal JA, Mestre MA (26 May 2017). "The Safety of Ingested Caffeine: A Comprehensive Review". Frontiers in Psychiatry. 8 (80): 80. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2017.00080. PMC 5445139. PMID 28603504.

- ^ Levounis P, Herron AJ (2014). The Addiction Casebook. American Psychiatric Pub. p. 49. ISBN 978-1-58562-458-4.

- ^ a b Schneider MB, Benjamin HJ, et al. (Committee on Nutrition and the Council on Sports Medicine and Fitness) (June 2011). "Sports drinks and energy drinks for children and adolescents: are they appropriate?". Pediatrics. 127 (6): 1182–1189. doi:10.1542/peds.2011-0965. PMID 21624882.

- ^ a b c d van Dam RM, Hu FB, Willett WC (July 2020). "Coffee, Caffeine, and Health". The New England Journal of Medicine. 383 (4): 369–378. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1816604. PMID 32706535. S2CID 220731550.

- ^ "Food Standards Agency publishes new caffeine advice for pregnant women". Archived from the original on 17 October 2010. Retrieved 3 August 2009.

- ^ Kuczkowski KM (November 2009). "Caffeine in pregnancy". Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 280 (5): 695–8. doi:10.1007/s00404-009-0991-6. PMID 19238414. S2CID 6475015.

- ^ Brent RL, Christian MS, Diener RM (April 2011). "Evaluation of the reproductive and developmental risks of caffeine". Birth Defects Research Part B: Developmental and Reproductive Toxicology. 92 (2): 152–87. doi:10.1002/bdrb.20288. PMC 3121964. PMID 21370398.

- ^ Chen LW, Wu Y, Neelakantan N, Chong MF, Pan A, van Dam RM (September 2014). "Maternal caffeine intake during pregnancy is associated with risk of low birth weight: a systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis". BMC Medicine. 12 (1): 174. doi:10.1186/s12916-014-0174-6. PMC 4198801. PMID 25238871.

- ^ Chen LW, Wu Y, Neelakantan N, Chong MF, Pan A, van Dam RM (May 2016). "Maternal caffeine intake during pregnancy and risk of pregnancy loss: a categorical and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective studies". Public Health Nutrition. 19 (7): 1233–44. doi:10.1017/S1368980015002463. PMC 10271029. PMID 26329421.

- ^ Lassi ZS, Imam AM, Dean SV, Bhutta ZA (September 2014). "Preconception care: caffeine, smoking, alcohol, drugs and other environmental chemical/radiation exposure". Reproductive Health. 11 (Suppl 3): S6. doi:10.1186/1742-4755-11-S3-S6. PMC 4196566. PMID 25415846.

- ^ Boekema PJ, Samsom M, van Berge Henegouwen GP, Smout AJ (1999). "Coffee and gastrointestinal function: facts and fiction. A review". Scandinavian Journal of Gastroenterology. Supplement. 34 (230): 35–9. doi:10.1080/003655299750025525. PMID 10499460.

- ^ Cohen S, Booth GH (October 1975). "Gastric acid secretion and lower-esophageal-sphincter pressure in response to coffee and caffeine". The New England Journal of Medicine. 293 (18): 897–9. doi:10.1056/NEJM197510302931803. PMID 1177987.

- ^ Sherwood L, Kell R (2009). Human Physiology: From Cells to Systems (1st Canadian ed.). Nelsen. pp. 613–9. ISBN 978-0-17-644107-4.

- ^ "Caffeine in the diet". MedlinePlus, US National Library of Medicine. 30 April 2013. Archived from the original on 5 January 2015. Retrieved 2 January 2015.

- ^ Rapuri PB, Gallagher JC, Kinyamu HK, Ryschon KL (November 2001). "Caffeine intake increases the rate of bone loss in elderly women and interacts with vitamin D receptor genotypes". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 74 (5): 694–700. doi:10.1093/ajcn/74.5.694. PMID 11684540.

- ^ Maughan RJ, Griffin J (December 2003). "Caffeine ingestion and fluid balance: a review" (PDF). Journal of Human Nutrition and Dietetics. 16 (6): 411–20. doi:10.1046/j.1365-277X.2003.00477.x. PMID 19774754. S2CID 41617469. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 March 2019.

- ^ 근위세관에서의 아데노신 수용체 발현 조절: 신장염 및 물 대사를 조절하기 위한 신규 적응기전 Am.J. 피지올.신장 물리학. 2008년 7월 1일 295:F35-F36

- ^ O'Connor A (4 March 2008). "Really? The claim: caffeine causes dehydration". New York Times. Archived from the original on 3 September 2011. Retrieved 3 August 2009.

- ^ Armstrong LE, Casa DJ, Maresh CM, Ganio MS (July 2007). "Caffeine, fluid-electrolyte balance, temperature regulation, and exercise-heat tolerance". Exercise and Sport Sciences Reviews. 35 (3): 135–40. doi:10.1097/jes.0b013e3180a02cc1. PMID 17620932. S2CID 46352603.

- ^ Maughan RJ, Watson P, Cordery PA, Walsh NP, Oliver SJ, Dolci A, et al. (March 2016). "A randomized trial to assess the potential of different beverages to affect hydration status: development of a beverage hydration index". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 103 (3): 717–23. doi:10.3945/ajcn.115.114769. PMID 26702122. S2CID 378245.

- ^ Tarnopolsky MA (2010). "Caffeine and creatine use in sport". Annals of Nutrition & Metabolism. 57 (Suppl 2): 1–8. doi:10.1159/000322696. PMID 21346331.

- ^ Winston AP (2005). "Neuropsychiatric effects of caffeine". Advances in Psychiatric Treatment. 11 (6): 432–439. doi:10.1192/apt.11.6.432.

- ^ Vilarim MM, Rocha Araujo DM, Nardi AE (August 2011). "Caffeine challenge test and panic disorder: a systematic literature review". Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics. 11 (8): 1185–95. doi:10.1586/ern.11.83. PMID 21797659. S2CID 5364016.

- ^ Smith A (September 2002). "Effects of caffeine on human behavior". Food and Chemical Toxicology. 40 (9): 1243–55. doi:10.1016/S0278-6915(02)00096-0. PMID 12204388.

- ^ Bruce MS, Lader M (February 1989). "Caffeine abstention in the management of anxiety disorders". Psychological Medicine. 19 (1): 211–4. doi:10.1017/S003329170001117X. PMID 2727208. S2CID 45368729.

- ^ Lara DR (2010). "Caffeine, mental health, and psychiatric disorders". Journal of Alzheimer's Disease. 20 (Suppl 1): S239–48. doi:10.3233/JAD-2010-1378. PMID 20164571.

- ^ Wang L, Shen X, Wu Y, Zhang D (March 2016). "Coffee and caffeine consumption and depression: A meta-analysis of observational studies". The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 50 (3): 228–42. doi:10.1177/0004867415603131. PMID 26339067. S2CID 23377304.

- ^ Grosso G, Micek A, Castellano S, Pajak A, Galvano F (January 2016). "Coffee, tea, caffeine and risk of depression: A systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of observational studies". Molecular Nutrition & Food Research. 60 (1): 223–34. doi:10.1002/mnfr.201500620. PMID 26518745.

- ^ Kohn R, Keller M (2015). "Chapter 34 Emotions". In Tasman A, Kay J, Lieberman JA, First MB, Riba M (eds.). Psychiatry. Vol. 1. New York: John Wiley & Sons. pp. 557–558. ISBN 978-1-118-84547-9.

Table 34-12... Caffeine Intoxication – Euphoria

- ^ Hrnčiarove J, Barteček R (2017). "8. Substance Dependence". In Hosák L, Hrdlička M, et al. (eds.). Psychiatry and Pedopsychiatry. Prague: Karolinum Press. pp. 153–154. ISBN 9788024633787.

At a high dose, caffeine shows a euphoric effect.

- ^ Schulteis G (2010). "Brain stimulation and addiction". In Koob GF, Le Moal M, Thompson RF (eds.). Encyclopedia of Behavioral Neuroscience. Elsevier. p. 214. ISBN 978-0-08-091455-8.

Therefore, caffeine and other adenosine antagonists, while weakly euphoria-like on their own, may potentiate the positive hedonic efficacy of acute drug intoxication and reduce the negative hedonic consequences of drug withdrawal.

- ^ Salerno BB, Knights EK (2010). Pharmacology for health professionals (3rd ed.). Chatswood, N.S.W.: Elsevier Australia. p. 433. ISBN 978-0-7295-3929-6.

In contrast to the amphetamines, caffeine does not cause euphoria, stereotyped behaviors or psychoses.

- ^ Ebenezer I (2015). Neuropsychopharmacology and Therapeutics. John Wiley & Sons. p. 18. ISBN 978-1-118-38578-4.

However, in contrast to other psychoactive stimulants, such as amphetamine and cocaine, caffeine and the other methylxanthines do not produce euphoria, stereotyped behaviors or psychotic like symptoms in large doses.

- ^ a b Addicott MA (September 2014). "Caffeine Use Disorder: A Review of the Evidence and Future Implications". Current Addiction Reports. 1 (3): 186–192. doi:10.1007/s40429-014-0024-9. PMC 4115451. PMID 25089257.

- ^ Nestler EJ, Hymen SE, Holtzmann DM, Malenka RC. "16". Molecular Neuropharmacology: A Foundation for Clinical Neuroscience (3rd ed.). McGraw-Hill Education.

True compulsive use of caffeine has not been documented, and, consequently, these drugs are not considered addictive.

- ^ Budney AJ, Emond JA (November 2014). "Caffeine addiction? Caffeine for youth? Time to act!". Addiction. 109 (11): 1771–2. doi:10.1111/add.12594. PMID 24984891.

Academics and clinicians, however, have not yet reached consensus about the potential clinical importance of caffeine addiction (or 'use disorder')

- ^ Meredith SE, Juliano LM, Hughes JR, Griffiths RR (September 2013). "Caffeine Use Disorder: A Comprehensive Review and Research Agenda". Journal of Caffeine Research. 3 (3): 114–130. doi:10.1089/jcr.2013.0016. PMC 3777290. PMID 24761279.

- ^ Riba A, Tasman J, Kay JS, Lieberman MB, First MB (2014). Psychiatry (Fourth ed.). John Wiley & Sons. p. 1446. ISBN 978-1-118-75336-1.

- ^ Fishchman N, Mello N. Testing for Abuse Liability of Drugs in Humans (PDF). Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Public Health Service Alcohol, Drug Abuse, and Mental Health Administration National Institute on Drug Abuse. p. 179. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 December 2016.

- ^ Nestler EJ (December 2013). "Cellular basis of memory for addiction". Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience. 15 (4): 431–43. doi:10.31887/DCNS.2013.15.4/enestler. PMC 3898681. PMID 24459410.

DESPITE THE IMPORTANCE OF NUMEROUS PSYCHOSOCIAL FACTORS, AT ITS CORE, DRUG ADDICTION INVOLVES A BIOLOGICAL PROCESS: the ability of repeated exposure to a drug of abuse to induce changes in a vulnerable brain that drive the compulsive seeking and taking of drugs, and loss of control over drug use, that define a state of addiction. ... A large body of literature has demonstrated that such ΔFosB induction in D1-type NAc neurons increases an animal's sensitivity to drug as well as natural rewards and promotes drug self-administration, presumably through a process of positive reinforcement

- ^ Miller PM (2013). "Chapter III: Types of Addiction". Principles of addiction comprehensive addictive behaviors and disorders (1st ed.). Elsevier Academic Press. p. 784. ISBN 978-0-12-398361-9. Retrieved 11 July 2015.

Astrid Nehlig and colleagues present evidence that in animals caffeine does not trigger metabolic increases or dopamine release in brain areas involved in reinforcement and reward. A single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) assessment of brain activation in humans showed that caffeine activates regions involved in the control of vigilance, anxiety, and cardiovascular regulation but did not affect areas involved in reinforcement and reward.

- ^ Nehlig A, Armspach JP, Namer IJ (2010). "SPECT assessment of brain activation induced by caffeine: no effect on areas involved in dependence". Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience. 12 (2): 255–63. doi:10.31887/DCNS.2010.12.2/anehlig. PMC 3181952. PMID 20623930.

Caffeine is not considered addictive, and in animals it does not trigger metabolic increases or dopamine release in brain areas involved in reinforcement and reward. ... these earlier data plus the present data reflect that caffeine at doses representing about two cups of coffee in one sitting does not activate the circuit of dependence and reward and especially not the main target area, the nucleus accumbens. ... Therefore, caffeine appears to be different from drugs of dependence like cocaine, amphetamine, morphine, and nicotine, and does not fulfil the common criteria or the scientific definitions to be considered an addictive substance.42

- ^ Temple JL (June 2009). "Caffeine use in children: what we know, what we have left to learn, and why we should worry". Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 33 (6): 793–806. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2009.01.001. PMC 2699625. PMID 19428492.

Through these interactions, caffeine is able to directly potentiate dopamine neurotransmission, thereby modulating the rewarding and addicting properties of nervous system stimuli.

- ^ "ICD-10 Version:2015". World Health Organization. 2015. Archived from the original on 2 November 2015. Retrieved 10 July 2015.

F15 Mental and behavioural disorders due to use of other stimulants, including caffeine ...

.2 Dependence syndrome

A cluster of behavioural, cognitive, and physiological phenomena that develop after repeated substance use and that typically include a strong desire to take the drug, difficulties in controlling its use, persisting in its use despite harmful consequences, a higher priority given to drug use than to other activities and obligations, increased tolerance, and sometimes a physical withdrawal state.

The dependence syndrome may be present for a specific psychoactive substance (e.g., tobacco, alcohol, or diazepam), for a class of substances (e.g., opioid drugs), or for a wider range of pharmacologically different psychoactive substances. [Includes:]

Chronic alcoholism

Dipsomania

Drug addiction - ^ a b c d Association American Psychiatry (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders : DSM-5 (5th ed.). Washington [etc.]: American Psychiatric Publishing. pp. 792–795. ISBN 978-0-89042-555-8.

- ^ a b Temple JL (June 2009). "Caffeine use in children: what we know, what we have left to learn, and why we should worry". Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 33 (6): 793–806. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2009.01.001. PMC 2699625. PMID 19428492.

- ^ a b c Desk reference to the diagnostic criteria from DSM-5. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association. 2013. pp. 238–239. ISBN 978-0-89042-556-5.

- ^ a b "ICD-11 – Mortality and Morbidity Statistics". icd.who.int. Archived from the original on 1 August 2018. Retrieved 18 November 2019.

- ^ 미국정신의학협회(2013)."물질과 관련된 그리고 중독성 장애"American Psychiological Publishing. pp. 1-2.2019년 11월 18일 회수.

- ^ "Information about caffeine dependence". Caffeinedependence.org. Johns Hopkins Medicine. 9 July 2003. Archived from the original on 23 May 2012. Retrieved 25 May 2012.

- ^ a b c Fredholm BB, Bättig K, Holmén J, Nehlig A, Zvartau EE (March 1999). "Actions of caffeine in the brain with special reference to factors that contribute to its widespread use". Pharmacological Reviews. 51 (1): 83–133. PMID 10049999.

- ^ Santos C, Costa J, Santos J, Vaz-Carneiro A, Lunet N (2010). "Caffeine intake and dementia: systematic review and meta-analysis". Journal of Alzheimer's Disease. 20 (Suppl 1): S187-204. doi:10.3233/JAD-2010-091387. PMID 20182026.

- ^ Panza F, Solfrizzi V, Barulli MR, Bonfiglio C, Guerra V, Osella A, et al. (March 2015). "Coffee, tea, and caffeine consumption and prevention of late-life cognitive decline and dementia: a systematic review". The Journal of Nutrition, Health & Aging. 19 (3): 313–28. doi:10.1007/s12603-014-0563-8. hdl:11586/145493. PMID 25732217. S2CID 8376733.

- ^ Muriel P, Arauz J (July 2010). "Coffee and liver diseases". Fitoterapia. 81 (5): 297–305. doi:10.1016/j.fitote.2009.10.003. PMID 19825397.

- ^ "Coffee and the Liver". British Liver Trust. Archived from the original on 12 May 2023. Retrieved 12 May 2023.

- ^ Hackett PH (2010). "Caffeine at high altitude: java at base cAMP". High Altitude Medicine & Biology. 11 (1): 13–7. doi:10.1089/ham.2009.1077. PMID 20367483.

- ^ Jiang X, Zhang D, Jiang W (February 2014). "Coffee and caffeine intake and incidence of type 2 diabetes mellitus: a meta-analysis of prospective studies". European Journal of Nutrition. 53 (1): 25–38. doi:10.1007/s00394-013-0603-x. PMID 24150256. S2CID 5566177.

Dose-response analysis suggested that incidence of T2DM decreased ...14% [0.86 (0.82-0.91)] for every 200 mg/day increment in caffeine intake.

- ^ Hong CT, Chan L, Bai CH (June 2020). "The Effect of Caffeine on the Risk and Progression of Parkinson's Disease: A Meta-Analysis". Nutrients. 12 (6): 1860. doi:10.3390/nu12061860. PMC 7353179. PMID 32580456.

- ^ Liu R, Guo X, Park Y, Huang X, Sinha R, Freedman ND, et al. (June 2012). "Caffeine intake, smoking, and risk of Parkinson disease in men and women". American Journal of Epidemiology. 175 (11): 1200–7. doi:10.1093/aje/kwr451. PMC 3370885. PMID 22505763.

- ^ Li M, Wang M, Guo W, Wang J, Sun X (March 2011). "The effect of caffeine on intraocular pressure: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Graefe's Archive for Clinical and Experimental Ophthalmology. 249 (3): 435–42. doi:10.1007/s00417-010-1455-1. PMID 20706731. S2CID 668498.

- ^ Desk reference to the diagnostic criteria from DSM-5. 2013. ISBN 978-0-89042-556-5. OCLC 825047464.

{{cite book}}:work=무시됨(도움말) - ^ a b "Caffeine (Systemic)". MedlinePlus. 25 May 2000. Archived from the original on 23 February 2007. Retrieved 3 August 2009.

- ^ Winston AP, Hardwick E, Jaberi N (2005). "Neuropsychiatric effects of caffeine". Advances in Psychiatric Treatment. 11 (6): 432–439. doi:10.1192/apt.11.6.432.

- ^ Iancu I, Olmer A, Strous RD (2007). "Caffeinism: History, clinical features, diagnosis, and treatment". In Smith BD, Gupta U, Gupta BS (eds.). Caffeine and Activation Theory: Effects on Health and Behavior. CRC Press. pp. 331–344. ISBN 978-0-8493-7102-8. Retrieved 15 January 2014.

- ^ a b "ICD-11 – Mortality and Morbidity Statistics". icd.who.int. Archived from the original on 1 August 2018. Retrieved 25 November 2019.

- ^ American Psychiatric Association (22 May 2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (Fifth ed.). American Psychiatric Association. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.988.5627. doi:10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596. hdl:2027.42/138395. ISBN 978-0-89042-555-8.

- ^ Carreon CC, Parsh B (April 2019). "How to recognize caffeine overdose". Nursing (Clinical tutorial). 49 (4): 52–55. doi:10.1097/01.NURSE.0000553278.11096.86. PMID 30893206. S2CID 84842436.

- ^ a b Fintel M, Langer GA, Duenas C (November 1984). "Effects of low sodium perfusion on cardiac caffeine sensitivity and calcium uptake". Journal of Molecular and Cellular Cardiology. 16 (11): 1037–1045. doi:10.1016/s0022-2828(84)80016-4. PMID 6520875.

- ^ a b Murray A, Traylor J (January 2019). "Caffeine Toxicity". StatPearls [Internet] (Mini-review). PMID 30422505.

- ^ "Caffeine C8H10N4O2". pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. National Center for Biotechnology Information. Archived from the original on 2 March 2022. Retrieved 1 March 2022.

- ^ Peters JM (1967). "Factors Affecting Caffeine Toxicity: A Review of the Literature". The Journal of Clinical Pharmacology and the Journal of New Drugs. 7 (3): 131–141. doi:10.1002/j.1552-4604.1967.tb00034.x. Archived from the original on 12 January 2012.

- ^ Evans J, Richards JR, Battisti AS (January 2019). "Caffeine". StatPearls [Internet] (Mini-review). PMID 30137774.

- ^ Carpenter M (18 May 2015). "Caffeine powder poses deadly risks". New York Times. Archived from the original on 25 January 2022. Retrieved 18 May 2015.

- ^ Rodopoulos N, Wisén O, Norman A (May 1995). "Caffeine metabolism in patients with chronic liver disease". Scandinavian Journal of Clinical and Laboratory Investigation. 55 (3): 229–42. doi:10.3109/00365519509089618. PMID 7638557.

- ^ Cheston P, Smith L (11 October 2013). "Man died after overdosing on caffeine mints". The Independent. Archived from the original on 12 October 2013. Retrieved 13 October 2013.

- ^ Prynne M (11 October 2013). "Warning over caffeine sweets after father dies from overdose". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 11 October 2013. Retrieved 13 October 2013.

- ^ "Caffeine Drug Monographs". UpToDate. Archived from the original on 25 April 2013. Retrieved 28 November 2018.

- ^ Mackay M, Tiplady B, Scholey AB (April 2002). "Interactions between alcohol and caffeine in relation to psychomotor speed and accuracy". Human Psychopharmacology. 17 (3): 151–6. doi:10.1002/hup.371. PMID 12404692. S2CID 21764730.

- ^ a b c Liguori A, Robinson JH (July 2001). "Caffeine antagonism of alcohol-induced driving impairment". Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 63 (2): 123–9. doi:10.1016/s0376-8716(00)00196-4. PMID 11376916.

- ^ Marczinski CA, Fillmore MT (August 2003). "Dissociative antagonistic effects of caffeine on alcohol-induced impairment of behavioral control". Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 11 (3): 228–36. doi:10.1037/1064-1297.11.3.228. PMID 12940502.

- ^ Zevin S, Benowitz NL (June 1999). "Drug interactions with tobacco smoking. An update". Clinical Pharmacokinetics. 36 (6): 425–438. doi:10.2165/00003088-199936060-00004. PMID 10427467. S2CID 19827114.

- ^ Bjørngaard JH, Nordestgaard AT, Taylor AE, Treur JL, Gabrielsen ME, Munafò MR, et al. (December 2017). "Heavier smoking increases coffee consumption: findings from a Mendelian randomization analysis". International Journal of Epidemiology. 46 (6): 1958–1967. doi:10.1093/ije/dyx147. PMC 5837196. PMID 29025033.

- ^ Benowitz NL (1990). "Clinical pharmacology of caffeine". Annual Review of Medicine. 41: 277–88. doi:10.1146/annurev.me.41.020190.001425. PMID 2184730.

- ^ Gilmore B, Michael M (February 2011). "Treatment of acute migraine headache". American Family Physician. 83 (3): 271–80. PMID 21302868.

- ^ Benzon H (12 September 2013). Practical management of pain (Fifth ed.). Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 508–529. ISBN 978-0-323-08340-9.

- ^ "Vitamin B4". R&S Pharmchem. April 2011. Archived from the original on 15 July 2011.

- ^ Gottwalt B, Prasanna T (29 September 2021). "Methylxanthines". StatPearls. PMID 32644591. Archived from the original on 20 March 2022. Retrieved 15 November 2021.

- ^ a b c Froestl W, Muhs A, Pfeifer A (2012). "Cognitive enhancers (nootropics). Part 1: drugs interacting with receptors" (PDF). Journal of Alzheimer's Disease. 32 (4): 793–887. doi:10.3233/JAD-2012-121186. PMID 22886028. S2CID 10511507. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 November 2020.

- ^ a b c d Ferré S (2008). "An update on the mechanisms of the psychostimulant effects of caffeine". J. Neurochem. 105 (4): 1067–1079. doi:10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.05196.x. PMID 18088379. S2CID 33159096.

On the other hand, our 'ventral shell of the nucleus accumbens' very much overlaps with the striatal compartment...

- ^ "World of Caffeine". World of Caffeine. 15 June 2013. Archived from the original on 10 December 2013. Retrieved 19 December 2013.

- ^ Fisone G, Borgkvist A, Usiello A (April 2004). "Caffeine as a psychomotor stimulant: mechanism of action". Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences. 61 (7–8): 857–72. doi:10.1007/s00018-003-3269-3. PMID 15095008. S2CID 7578473.

- ^ "Caffeine". IUPHAR. International Union of Basic and Clinical Pharmacology. Archived from the original on 2 November 2014. Retrieved 2 November 2014.

- ^ Duan L, Yang J, Slaughter MM (August 2009). "Caffeine inhibition of ionotropic glycine receptors". The Journal of Physiology. 587 (Pt 16): 4063–75. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.2009.174797. PMC 2756438. PMID 19564396.

- ^ a b c Ferré S (2010). "Role of the central ascending neurotransmitter systems in the psychostimulant effects of caffeine". Journal of Alzheimer's Disease. 20 (Suppl 1): S35–49. doi:10.3233/JAD-2010-1400. PMC 9361505. PMID 20182056.

By targeting A1-A2A receptor heteromers in striatal glutamatergic terminals and A1 receptors in striatal dopaminergic terminals (presynaptic brake), caffeine induces glutamate-dependent and glutamate-independent release of dopamine. These presynaptic effects of caffeine are potentiated by the release of the postsynaptic brake imposed by antagonistic interactions in the striatal A2A-D2 and A1-D1 receptor heteromers.

- ^ a b Ferré S, Bonaventura J, Tomasi D, Navarro G, Moreno E, Cortés A, Lluís C, Casadó V, Volkow ND (May 2016). "Allosteric mechanisms within the adenosine A2A-dopamine D2 receptor heterotetramer". Neuropharmacology. 104: 154–60. doi:10.1016/j.neuropharm.2015.05.028. PMC 5754196. PMID 26051403.

- ^ a b Bonaventura J, Navarro G, Casadó-Anguera V, Azdad K, Rea W, Moreno E, Brugarolas M, Mallol J, Canela EI, Lluís C, Cortés A, Volkow ND, Schiffmann SN, Ferré S, Casadó V (July 2015). "Allosteric interactions between agonists and antagonists within the adenosine A2A receptor-dopamine D2 receptor heterotetramer". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 112 (27): E3609–18. Bibcode:2015PNAS..112E3609B. doi:10.1073/pnas.1507704112. PMC 4500251. PMID 26100888.