에마뉘엘 마크롱

Emmanuel Macron이 기사는 너무 길어서 편하게 읽고 탐색할 수 없습니다. (2023년 8월) |

에마뉘엘 마크롱 | |

|---|---|

2023년 마크롱 | |

| 프랑스 제25대 대통령 | |

| 가임직 2017년 5월 14일 | |

| 수상 | 에두아르 필리프 장 카스텍스 엘리자베스 보른 가브리엘 아탈 |

| 앞에 | 프랑수아 올랑드 |

| 경제산업디지털부 장관 | |

| 재직중 2014년 8월 26일 ~ 2016년 8월 30일 | |

| 수상 | 마누엘 발스 |

| 앞에 | 아르노 몬테부르 |

| 성공자 | 미셸 사핀 |

| 대통령 사무차장 | |

| 재직중 2012년 5월 15일 ~ 2014년 7월 15일 | |

| 대통령 | 프랑수아 올랑드 |

| 앞에 | 장 카스텍스 |

| 성공자 | 로렌스 분 |

| 추가 포지션 | |

| 인적사항 | |

| 태어난 | 에마뉘엘 장 미셸 프레데릭 마크롱 1977년 12월 21일 아미앵, 솜, 프랑스 |

| 정당 | 르네상스 (2016~현재) |

| 기타정치 계열사들 | |

| 배우자. | |

| 부모 |

|

| 친척들. | 로랑스 외제르 주르단(계녀) |

| 사는곳 | 엘리제궁 |

| 모교 | |

| 상 | 훈장 목록 |

| 서명 |  |

| 안도라 공국[주1] | |

| 재위 | 2017년 5월 14일 ~ 현재 |

| 전임자 | 프랑수아 올랑드 |

| ||

|---|---|---|

사장(2017~현재)

미디어 갤러리 | ||

에마뉘엘 장 미셸 프레데릭 마크롱(Emmanuel Jean-Michel Frédéric Macron) ɥɛ 막 ʁɔ̃(, 1977년 12월 21일 ~ )는 프랑스의 정치인으로, 2017년부터 프랑스의 대통령을 맡고 있습니다. 마크롱은 직권으로 안도라의 두 공동 왕자 중 한 명입니다. 그는 이전에 2014년부터 2016년까지 프랑수아 올랑드 대통령 하에서 경제산업디지털부 장관을 지냈고, 2012년부터 2014년까지 대통령의 사무차장을 지냈습니다. 그는 중도 정당인 르네상스의 창립 멤버입니다.

아미앵에서 태어난 마크롱은 파리 낭테르 대학교에서 철학을 공부했고, 나중에 사이언스 포에서 행정학 석사를 마치고 2004년 에콜 국립 행정부를 졸업했습니다. 그는 재무 검사국에서 고위 공무원으로 일했고, 나중에 로스차일드 & Co에서 투자 은행가가 되었습니다.

2012년 5월 당선 직후 프랑수아 올랑드 대통령에 의해 엘리제 사무차장으로 임명된 마크롱은 올랑드의 수석 고문 중 한 명이었습니다. 발스 2기 정부에서 2014년 8월 경제산업디지털부 장관으로 임명된 그는 여러 가지 기업 친화적인 개혁을 주도했습니다. 그는 2017년 대선 캠페인을 시작하기 위해 2016년 8월 사임했습니다. 2006년부터 2009년까지 사회당 소속이었던 그는 2016년 4월 자신이 창당한 중도·친유럽 정치 운동인 엔마르슈(En Marche)를 기치로 내걸고 선거에 출마했습니다.

부분적으로 공화당 후보 프랑수아 피용의 기회를 침몰시킨 피용 사건의 결과로 마크롱은 1차 투표에서 1위를 차지했고, 2017년 5월 7일 2차 투표에서 66.1%의 득표율로 국민전선의 마린 르펜을 누르고 프랑스 대통령에 당선되었습니다. 39세의 나이로 그는 프랑스 역사상 최연소 대통령이 되었습니다. 2017년 6월 총선에서 라 레퓌블리크 앙마르슈(La République En Marche!)로 이름을 바꾼 그의 정당은 국회에서 과반수를 확보했습니다. 그는 에두아르 필리프를 총리로 임명했습니다. 2020년 필리프가 사임하자 마크롱은 장 카스텍스를 후임으로 임명했습니다.

마크롱은 2022년 대선에서 르펜을 다시 꺾고 재선에 성공한 첫 프랑스 대선 후보가 됐습니다. 그러나 2022년 총선에서 그의 중도파 연합은 절대 다수를 잃었고, 그 결과 헝 의회와 1993년 베레고보이 정부의 붕괴 이후 프랑스 최초의 소수 정부가 형성되었습니다. 마크롱의 현 총리는 프랑스 역사상 최연소 정부 수반이자 첫 번째 공개 동성애자로, 주요 정부 위기 후 2024년 1월 프랑스의 두 번째 여성 총리인 엘리자베스 보른의 후임으로 임명했습니다.

마크롱은 그의 대통령 재임 기간 동안 노동법, 세금, 연금에 대한 여러 개혁을 감독했고 재생 가능한 에너지 전환을 추구했습니다. 정적들에 의해 "부자의 대통령"이라고 불리는 그의 국내 개혁에 반대하는 시위를 증가시키고 그의 사임을 요구하는 그의 대통령 임기 첫 해를 기념했고, 노란 조끼 시위와 연금 개혁 파업으로 2018-2020년에 절정에 이르렀습니다. 2020년부터 프랑스의 코로나19 팬데믹 대응과 백신 출시를 이끌었습니다. 2023년, 그의 총리인 엘리자베스 보른의 정부는 은퇴 연령을 62세에서 64세로 올리는 법안을 통과시켰습니다. 연금 개혁은 논란의 여지가 있는 것으로 판명되었고 공공 부문 파업과 폭력 시위로 이어졌습니다. 외교정책에서 그는 유럽연합(EU)에 개혁을 요구했고 이탈리아, 독일과 양자 조약을 체결했습니다. 마크롱은 중·미 무역전쟁 당시 중국과 420억 유로의 무역 및 업무협약을 체결했으며, 호주 및 미국과 AUKUS 안보협정을 둘러싼 분쟁을 감독했습니다. 그는 이슬람 국가와의 전쟁에서 참말 작전을 계속했고 2022년 러시아의 우크라이나 침공에 대한 국제적 비난에 동참했습니다.

초기생

마크롱은 1977년 12월 21일 아미앵에서 태어났습니다. 그는 의사인 프랑수아즈 마크롱(성 노게스)과 피카르디 대학의 신경학 교수인 장 미셸 마크롱의 아들입니다.[1][2] 이 부부는 2010년에 이혼했습니다. 그에게는 1979년생 로랑과 1982년생 에스텔이라는 두 남매가 있습니다. 프랑수아즈와 장 미셸의 첫 아이는 사산했습니다.[3]

마크롱 가문의 유산은 피카디의 오티 마을까지 거슬러 올라갑니다.[4] 그의 친증조부 중 한 명인 조지 윌리엄 로버트슨은 영국인이었고 영국 브리스톨에서 태어났습니다.[5][6] 그의 외조부모 장과 제르맹 노귀스(성 아리베트)는 피레네아인 마을인 가스코니의 바그너레스-드-비고레 출신입니다.[7] 그는 흔히 그의 할머니 저메인을 방문하기 위해 바그너레스 드 비고레를 방문했고, 그는 그를 "마네트"라고 불렀습니다.[8] 마크롱은 그의[9] 독서의 즐거움과 좌파적인 정치적 성향을 역장 아버지와 가사 어머니의 소박한 성장 후 교사가 된 후 교장이 되었고 2013년에 사망한 저메인과 연관시킵니다.[10]

비록 종교가 없는 가정에서 자랐지만, 마크롱은 12살에 자신의 요청으로 가톨릭 신자에게 세례를 받았습니다; 그는 오늘날 불가지론자입니다.[11]

마크롱은 그의 부모가 그를 파리의 엘리트 리세 앙리-4세에서 마지막[14] 학년을 마치도록 보내기 전에 아미앵에[13] 있는 예수회 기관인[12] 리세 라 프로비던스에서 주로 교육을 받았습니다. 그는 고등학교 과정과 학부 과정을 "Bac S, Mention Trèsbien"으로 마쳤습니다. 동시에, 그는 프랑스 문학 콩쿠르(가장 선별적인 전국 수준의 고등학교 콩쿠르)에 지명되었고, 아미앵 음악원에서 피아노 공부로 졸업장을 받았습니다.[15] 그의 부모는 그가 나중에 그의 아내가 된 예수이테스 데 라 프로비던스의 세 자녀를 둔 결혼한 교사 브리지트 외지에르와 맺은 유대에 대한 경각심 때문에 그를 파리로 보냈습니다.[16]

파리에서 마크롱은 에콜 노르말 수페리외르에 입성하는 데 두 번이나 실패했습니다.[17][18][19] 그는 대신 파리 대학교에서 철학을 공부하여 DEA 학위(석사학위)를 취득했으며, 마키아벨리와 헤겔에 관한 논문을 작성했습니다.[12][20] 1999년경 마크롱은 프랑스 개신교 철학자 폴 리쾨르의 편집 조수로 일했는데, 폴 리쾨르는 그의 마지막 주요 작품인 '라 메무아르', '라 히스토아르', '루블리'를 집필하고 있었습니다. 마크롱은 주로 노트와 서지학을 연구했습니다.[21][22] 마크롱은 문학 잡지 에스프리트의 편집위원이 되었습니다.[23]

마크롱은 대학원 공부를 하기 때문에 국가 봉사를 하지 않았습니다. 1977년 12월에 태어난 그는 병역이 의무화된 마지막 코호트에 속했습니다.[24][25]

마크롱은 선택적 에콜 국가 행정부(ENA)에서 고위 공무원 경력을 위한 훈련, 주나이지리아[26] 프랑스 대사관 및 오이세 현에서 훈련을 받기 전에 사이언스 포에서 "공공 지도 및 경제"를 전공한 공무원 석사 학위를 취득했습니다.[27]

직업경력

금융감독관

2004년 ENA를 졸업한 후, 마크롱은 재무부의 한 부서인 Inspection Genérale des Financial (IGF)의 검사관이 되었습니다.[21] 마크롱은 당시 인터넷 연맹의 수장이었던 장 피에르 주예로부터 조언을 받았습니다.[28] 마크롱은 재정 조사관으로 있는 동안 여름 동안 "준비"에서 강연을 했습니다.IPESUP의 ENA"(ENA 입시를 위한 특별 입시 학원)는 HEC 또는 사이언스 포와 같은 그랑제콜 입시 준비를 전문으로 하는 엘리트 사립 학교입니다.[29][30][31]

2006년, Laurence Parisot는 그에게 프랑스에서 가장 큰 고용주 연맹인 Mouvement des Entrepresis de France의 상무이사직을 제안했지만, 그는 거절했습니다.[32]

2007년 8월, 마크롱은 자크 아탈리의 "프랑스 성장을 시작하기 위한 위원회"의 부보고관으로 임명되었습니다.[13] 2008년 마크롱은 5만 유로를 지불하고 정부 계약에서 자신을 구입했습니다.[33] 그 후 그는 로스차일드 & Cie Banque에서 고액의 보수를 받는 투자 은행가가 되었습니다.[34][35] 2010년 3월, 그는 아탈리 위원회의 위원으로 임명되었습니다.[36]

투자은행가

2008년 9월, 마크롱은 재무 검사관직을 그만두고 로스차일드 & 시에 방크에서 자리를 잡았습니다.[37] 마크롱은 니콜라 사르코지가 대통령이 되었을 때 정부를 떠났습니다. 그는 원래 프랑수아 헨로트로부터 그 일을 제안 받았습니다. 은행에서 그의 첫 번째 책임은 Cédit Mutuel Nord Europe가 Cofidis를 인수하는 것을 도왔습니다.[38]

마크롱은 르몽드 감독이사회의 사업가 알랭 민크와 인연을 맺었습니다.[39] 2010년, 마크롱은 Le Monde의 자본재편과 Siemens IT Solutions and Services의 Atos에 의한 인수 작업을 거쳐 은행의 파트너로 승진했습니다.[40] 같은 해 마크롱은 네슬레가 화이자의 유아 영양 사업부를 90억 유로에 인수한 것을 책임지게 되었고, 이로 인해 그는 백만장자가 되었습니다.[41][42]

2012년 2월, 그는 에이브릴 그룹의 CEO인 사업가 필립 틸러스 보르드에게 조언했습니다.[43]

마크롱은 2010년 12월부터 2012년 5월까지 2백만 유로를 벌었다고 발표했습니다.[44] 공식 문서에 따르면 마크롱은 2009년에서 2013년 사이에 거의 300만 유로를 벌었습니다.[45] 그는 2012년 로스차일드 & Cie를 떠났습니다.[46][47]

정치경력

마크롱은 젊은 시절 2년간 시민공화운동에서 일했지만, 한 번도 회원 신청을 하지 않았습니다.[48][44] 마크롱은 사이언스 포에 있는 동안 파리 11구의 조르주 사레 시장의 조수였습니다.[49] 마크롱은 24살 때부터 사회당의 일원이었지만,[50] 2006-2009년 기간 동안 마지막으로 그의 회원 자격을 갱신했습니다.[51]

마크롱은 2006년 장피에르 주예트를 통해 프랑수아 올랑드를 만났고, 2010년 그의 참모진에 합류했습니다.[50] 2007년, 마크롱은 2007년 총선에서 사회당 소속으로 피카르디 국회의원 출마를 시도했지만, 그의 신청은 거절당했습니다.[52] 마크롱은 2010년 프랑수아 피용 총리의 부비서실장직을 제안받았지만 거절했습니다.[53]

엘리제 사무차장

2012년 5월 15일, 마크롱은 프랑수아 올랑드 대통령의 비서실에서 수석 역할을 하는 엘리제 사무차장이 되었습니다.[54][27] 마크롱은 니콜라스 레벨과 함께 일했습니다. 그는 피에르 르네 레마스 사무총장 밑에서 일했습니다.

2012년 여름, 마크롱은 주 35시간 근무를 2014년까지 37시간으로 늘리는 제안을 내놓았습니다. 그는 또한 정부가 계획한 최고 소득자에 대한 많은 세금 인상을 억제하려고 노력했습니다. 올랑드 대통령은 마크롱 대통령의 제안을 거부했습니다.[55] 2013년에 그는 CEO의 급여를 규제하는 것에 반대하는 결정적인 투표 중 하나였습니다.[56] 엘리제의 다른 사무차장인 니콜라스 레블은 메데프가 선호하는 예산책임협약 제안에 대해 마크롱을 반대했습니다.[57]

2014년 6월 10일, 마크롱이 그의 역할에서 사임하고 로렌스 분으로 교체되었음을 발표했습니다.[58] 그가 떠난 이유로는 마누엘 발스 초대 정부에 포함되지 못한 것에 대한 실망감과 정부가 제안한 개혁에 대한 영향력 부족에 대한 좌절감이 있습니다.[57] 이것은 장 피에르 주예를 비서실장으로 임명한 이후의 일이었습니다.[59]

주예트는 마크롱이 "개인적인 열망을 지속하고"[60] 자신의 금융 컨설팅 회사를 만들기 위해 떠났다고 말했습니다.[61] 그는 교육 사업에 자금을 대는 투자 회사를 설립할 계획이었던 것으로 나중에 알려졌습니다.[48] 얼마 지나지 않아 그는 베를린 대학의 연구원으로 고용되어 사업가 알랭 민크의 도움을 받았습니다. 그는 또한 하버드 대학에서 자리를 구했습니다.[62]

마크롱은 2014년 고향 아미앵에서 지방선거에 후보로 나설 기회를 제공받았지만 거절했고,[63] 프랑수아 올랑드가 자신이 공직에 당선된 적이 없기 때문에 그를 예산 장관으로 임명하려는 마누엘 발스의 제안을 거부하도록 이끌었습니다.[59]

경제산업부 장관

2014년 8월 26일 제2차 발스 내각에서 아르노 몬테부르의 후임으로 경제산업부 장관에 임명되었습니다.[64] 그는 1962년 발레리 지스카르 데스탱 이후 최연소 경제부 장관이었습니다.[65] 마크롱은 친유럽연합(EU) 성향과 훨씬 온건한 성향 때문에 언론에 의해 '반(反)몽테부르'로 낙인찍힌 반면, 몬테부르는 유로 회의적이고 좌파적이었습니다.[66] 마크롱은 경제부 장관으로서 기업 친화적인 개혁을 추진하는 데 앞장섰습니다. 2015년 2월 17일, 마누엘 발스 총리는 49.3 특별 절차를 사용하여 마지못해 의회를 통과하여 마크롱의 서명법 패키지를 밀어붙였습니다.[67]

마크롱은 르노에 대한 프랑스인 지분을 15%에서 20%로 늘린 뒤 주주 3분의 2가 이를 뒤집기 위해 투표하지 않으면 2년 이상 등록된 주식에 대해 이중 의결권을 부여하는 플로랑주법을 시행했습니다.[68] 마크롱은 나중에 정부가 르노 내에서 권한을 제한할 것이라고 말했지만, 이것은 프랑스 주에 그 회사의 소수 지분을 주었습니다.[69]

마크롱은 이세레에 있는 에코플라 공장의 폐쇄를 막을 수 없다는 비난을 많이 받았습니다.[70]

2015년 8월, 마크롱은 더 이상 사회당의 일원이 아니며 무소속이라고 말했습니다.[51]

마크롱 로

원래 아르노 몬테부르가 정부를 떠나기 전에 후원을 받아 "권력 구매"에 중점을 두었던 법은 일요일과 밤에 일하는 것을 금지하는 법을 자유화하는 조치인으로 성장했습니다 변호사와 경매인; 그리고 민간 회사들로부터 군이 장비를 대여하는 것을 관리하는 규칙들. 이 법은 또한 운전면허를 취득하는 것과 같은 많은 정부 절차를 간소화하려고 했습니다.[71][72] 마누엘 발스([74]Manuel Valls)는 국회에서 통과되지 못할 것을 우려하여 법을 49.3 절차로[73][67] 추진하기로 결정하여 2015년 4월 10일 채택되었습니다.

이 법이 발생시킬 수 있는 GDP 증가에 대한 추정치는 0.3%에서 0.[75][76]5% 사이였습니다.

2017년 대통령 선거운동

앙마르슈의 결성과 정부 퇴진

마크롱은 2015년 3월 프랑스 TV 프로그램 Des Paroles et Des Actes에 출연한 후 프랑스 대중에게 처음 알려졌습니다.[77] 그의 정당인 앙마르슈를 창당하기 전, 그는 2015년 3월 발드마르네에서 처음으로 여러 차례 연설을 했습니다.[78] 그는 테러범들로부터 이중국적을 제거하자는 제안에 대해 마누엘 발스의 두 번째 정부를 떠나겠다고 위협했습니다.[79][80] 그는 또한 디지털 기술의 발전에 대해 연설한 이스라엘을 포함하여 다양한 해외 여행을 했습니다.[81]

마크롱이 자신의 원래 법보다 범위가 넓었던 '마크롱 2'라는 법안을 거부하면서 발스 정부와 올랑드 대통령에 대한 충성심 문제를 둘러싼 긴장감이 높아졌습니다.[82][83] 마크롱은 다른 장관들의 도움으로 그것들을 뒤집을 수 있었지만, 엘 콤리 법의 초안을 작성하고 "마크롱 2"의 특정 부분을 법에 넣는 것을 도울 기회가 주어졌습니다.[citation needed][clarification needed]

현 정부와의 긴장과 관계 악화 속에서 마크롱은 2016년 4월 6일 아미앵에서 독립 정당인 엔마르슈를 창당했습니다.[84] 창당 당시 엄청난 언론 보도를 모았던 진보적[86][87] [85]정치 운동,[88] 당과 마크롱 모두 올랑드 대통령의 질책을 받고 마크롱의 정부에 대한 충성도 문제가 제기됐습니다.[89][90] 마누엘 발스,[92] 미셸 사핀,[93] 악셀 르메르, 크리스티안 에커트 등 사회당의 대다수가 앙마르슈에 반대하는 발언을 했음에도 불구하고 몇몇 의원들은 앙마르슈[91] 운동을 지지하는 목소리를 냈습니다.[94]

2016년 6월, 마크롱과 그의 운동인 앙마르슈(En Marche)에 대한 지지가 언론에서 증가하기 시작했고, 르익스프레스(L'Express), 르에초스(Les Echos), 르1(Le 1 로피니언(L'Opinion)이 그를 지지하기 시작했다고 보도했습니다.[95] 노동조합원들과 그들의 시위를 둘러싼 여러 논란들 이후, 주요 신문들이 마크롱과 엔마르슈에 관한 기사들을 1면에 게재하기 시작했다고 Acrimed[는 보도했습니다.[96] 극좌파와 극우파 모두에게 비판을 받은 이들 언론의 친 마크롱 인플루언서들은 '마크롱족'이라고 불렸습니다.[97][98]

2016년 5월 올리비에 카레(Olivier Carré) 올리비에(Olivier) 오를레앙 공방전 당시 잔 다르크(Joan of Arc)의 노력 587주년을 기념하는 축제에 마크롱을 초대했습니다.[99][100] LCI는 마크롱이 극우파로부터 잔 다르크 상징을 되찾으려 한다고 보도했습니다.[101] 마크롱은 이후 푸이 뒤 푸이 뒤 푸이를 찾아가 현 정부를 떠날 것이라는 소문 속에 연설을 통해 "사회주의자가 아니다"라고 선언했습니다.[102] 2016년 8월 30일, 마크롱은 2017년 대통령 선거를 앞두고 자신의 앙마르슈 운동에 [103][104]전념하기 위해 정부에서 사임했습니다.[105][106] 2015년 초부터 그가 발스 정부를 떠나고 싶어했다는 여러 보도와 긴장이 고조되고 있었습니다.[107] 당초 '마크롱2' 법이[clarification needed][83] 취소된 뒤 떠날 계획이었지만 프랑수아 올랑드 대통령과 회동한 뒤 일시적으로 머물기로 했습니다.[108] 올랑드 대통령은 마크롱의 [109]후임으로 미셸 사핀이 발표됐고, 올랑드 대통령은 마크롱이 자신을 "조직적으로 배신했다"고 느꼈다고 말했습니다.[110] IFOP 여론조사에 따르면 조사 대상자의 84%가 그의 사임 결정에 동의했습니다.[111]

대통령 선거 제1차 투표

마크롱은 처음엔 앙마르슈를 결성해 출마 의사를 밝혔지만, 정부 퇴진에 따라 자신의 운동에 더 많은 시간을 바칠 수 있게 됐습니다. 그는 2016년 4월 대선 출마를 고려하고 있다고 처음 밝혔고,[112] 경제부 장관직에서 물러난 뒤 언론 매체들은 그가 출마할 것을 암시하는 모금의 패턴을 파악하기 시작했습니다.[113] 2016년 10월 마크롱은 올랑드의 '정상적인' 대통령 목표를 비판하면서 프랑스는 더 많은 '유피테르 대통령직'이 필요하다고 말했습니다.[114]

2016년 11월 16일, 마크롱은 수개월 간의 추측 끝에 프랑스 대통령 출마를 공식 선언했습니다. 그는 발표 연설에서 "민주주의 혁명"을 촉구하고 "프랑스의 봉쇄를 해제하겠다"고 약속했습니다.[115] 그는 올랑드가 현직 대통령으로서 정당한 사회당 후보라고 말하면서 몇 달 전에 출마할 것이라는 희망을 나타냈습니다.[116][117] 마크롱의 책 레볼루션은 2016년 11월 24일에 출판되었고 2016년 12월에 프랑스 베스트셀러 5위에 올랐습니다.[118]

출마를 선언한 직후, 장 크리스토프 캄바델리스와 마누엘 발스는 마크롱에게 사회당 대선 예비선거에 출마할 것을 요청했지만, 그는 결국 출마를 거부했습니다.[119][120] 장 크리스토프 캄바델리스는 제라르 콜롱 리옹 시장이 마크롱을 지지하자 마크롱을 지지하거나 지지하는 의원들을 배제하겠다고 위협하기 시작했습니다.[121]

프랑스 경제학자 소피 페라치가 대표로 있는 [122]마크롱의 선거운동은 2016년 12월 당시 선두 주자였던 알랭 주페의 [123]3배에 달하는 370만 유로의 기부금을 모금했다고 발표했습니다.[124] 마크롱은 베노 î트 하몬을 포함한 몇몇 사람들로부터 비난을 받았는데, 그는 기부자들의 명단을 공개해달라고 요청했고, 그가 로스차일드에서 보낸 시간 때문에 이해충돌이 있다고 비난했고, 마크롱은 이를 "낙하산"이라고 일축했습니다. 언론인 마리옹 라워와 프레데릭 세이즈는 이후 베르시에 있는 동안 언론과 프랑스 대중문화에서 다양한 인물들과 만찬과 모임을 마련하는 데 12만 유로를 썼다고 보도했습니다.[127] 크리스티앙 야곱과 필리프 비기에는 그가 선거운동을 하지 않고 이 돈을 선거운동에 사용했다고 비난했습니다.[128] 그의 후임자인 미셸 사핀은 그가 자금을 쓸 권리가 있다고 말하면서 그의 행동에 대해 불법적인 것은 아무것도 없다고 봤습니다.[129] 마크롱은 이 같은 의혹을 "명예훼손적"이라고 규정하고 장관 예산이 자신의 당에 지출된 적이 없다고 말했습니다.[127]

마크롱의 선거 운동은 언론의 상당한 보도를 누렸습니다.[130] 미디어파트는 50개가 넘는 잡지 표지가 전적으로 그에게 바쳐졌다고 보도했습니다.[131] 르몽드와[132] 누벨 전망대의 전 소유주 클로드 페르디엘의 친구였던 [133]그는 극좌파와 극우파에 의해 "언론 후보"로 분류되었고 여론조사에서 그렇게 여겨졌습니다.[134][135][136] 많은 관측통들은 그의 캠페인을 전 퍼블리시티 CEO인 모리스 레비가 그의 대통령 야망을 진전시키기 위해 마케팅 전술을 사용했기 때문에 판매되고[137] 있는 제품에 비교했습니다.[138][139] 잡지 마리안은 패트릭 드레이가 소유한 BFM TV가 다른 주요 후보를 모두 합친 것보다 마크롱에 대한 보도를 더 많이 내보냈다고 보도했습니다.[140] 마리안느는 이것이 베르나르 모라드를 통한 드라히와의 캠페인 연계 때문일 것이라고 추측했습니다.[141][142]

마크롱과 비교당했던 프랑수아 바이루는 대선에 나서지 않겠다고 선언하고 대신 여론조사 지지율이 상승하기 시작한 [143][144]마크롱과 선거 동맹을 맺었습니다. 프랑수아 피용을 둘러싼 몇 가지 법적 문제가 공론화된 후, 마크롱은 투표에서 그를 제치고 선두가 되었습니다.[145][146]

마크롱은 선거 운동 기간 동안 공식적인 프로그램을 설명하는 데 걸린 시간에 대해 비판을 받았습니다. 11월에 그가 여전히 2월까지 완전한 제안을 발표하지 않았다고 선언했음에도 불구하고 비판자들의 공격과 동맹국과 지지자들 사이의 우려를 모두 끌어들였습니다.[147] 그는 결국 3월 2일 150페이지 분량의 공식 프로그램을 발표하고, 온라인에 공개하고 그날 마라톤 기자회견에서 토론했습니다.[148]

마크롱은 민주운동(MoDem)의 프랑수아 바이루(François Bayrou), 다니엘 콘-벤디트(Daniel Cohn-Bendit), 좌파 경선의 생태학자 후보 프랑수아 드 뤼기(François de Lugy), 사회당의 리처드 페랑(Richard Ferrand) 의원 등으로부터 지지를 확보하며 광범위한 지지층을 축적했습니다. 사회당 출신의 많은 사람들 뿐만 아니라 중도와 중도 우파 정치인들도 다수 포함되어 있습니다.[149] 파리의 그랜드 모스크는 프랑스 이슬람교도들에게 마크롱에게 집단 투표할 것을 촉구했습니다.[150]

2017년 4월 23일, 마크롱은 대선 1차 투표에서 800만 표(24%) 이상을 얻어 가장 많은 표를 얻었고, 2차 투표에서 프랑수아 피용, 베노 î트 하몽 전 후보와 프랑수아 올랑드 현 대통령의 지지를 받으며 마린 르펜과 맞붙었습니다.

제2차 대통령 선거

장 클로드 융커 유럽연합 집행위원장, 앙겔라 메르켈 독일 총리,[153] 버락 오바마 전 미국 대통령 등 많은 외국 정치인들이 우파 표퓰리즘 후보 마린 르펜을 상대로 마크롱을 지지했습니다.[154]

2017년 5월 3일 마크롱과 르펜 사이에 토론이 마련되었습니다. 토론은 2시간 동안 계속됐고 여론조사 결과 그가 승리한 것으로 나타났습니다.[155]

2017년 3월, 마크롱의 디지털 선거 운동 관리자인 무니르 마주비는 영국 스카이 뉴스에 러시아가 마크롱에 대한 "높은 수준의 공격"의 배후에 있다고 말했고, 국영 언론은 "허위 정보의 첫 번째 출처"라고 말했습니다. 그는 "우리는 RT(옛 러시아투데이)와 스푸트니크 뉴스(스푸트니크 뉴스)가 우리 후보에 대해 공유한 첫 번째 허위 정보 출처라고 비난하고 있다"[156]고 말했습니다.

5월 7일 프랑스 대선을 이틀 앞두고 마크롱의 선거운동 이메일 9기가바이트가 문서 공유 사이트인 페이스트빈에 익명으로 게시된 것으로 알려졌습니다. 그리고 나서 이 문서들은 이미지보드 4chan에 퍼졌고, 이것은 해시태그 "#macron leaks"가 트위터에서 유행하게 만들었습니다.[157][158] 같은 날 저녁 마크롱의 정치 운동인 엔마르슈는 성명을 통해 "엔마르슈 운동은 오늘 저녁 다양한 내부 정보의 소셜 미디어 확산을 야기한 대규모 조정 해킹의 희생물이 되었습니다."[159]라고 말했습니다. 마크롱의 캠페인은 앞서 2017년 3월 일본 사이버 보안 회사 트렌드 마이크로(Trend Micro)가 엔마르슈가 피싱 공격의 표적이 된 방법을 자세히 설명하는 보고서를 발표했습니다.[160] 트렌드 마이크로(Trend Micro)는 이러한 공격을 수행한 그룹이 2016년 7월 22일 민주당 전국위원회를 해킹한 혐의를 받고 있는 러시아 해킹 그룹 팬시 베어(Fancy Bear)라고 말했습니다.[160] 위키리크스는 2017년 7월 21,075개의 확인된 이메일과 확인할 수 없는 또 다른 50,773개의 이메일을 공개했습니다.[161] 이는 르펜이 마크롱의 조세 회피 행위를 고발한 데 이은 것입니다.[162]

2017년 5월 7일, 마크롱은 66.1%의 득표율로 마린 르펜의 33.9%를 얻어 프랑스의 대통령으로 선출되었습니다. 이번 선거는 기권율이 25.4%로 기록적이었고, 8%의 투표용지가 공란이거나 변질됐습니다.[163] 마크롱은 앙마르슈[164] 대통령직에서 물러났고 캐서린 바르바루가 임시 지도자가 되었습니다.[165]

프랑스의 대통령

초선

마크롱은 2017년 4월 23일 1차 투표를 거쳐 결선투표에 진출했습니다. 그는 2017년 5월 7일 대선 2차 투표에서 예비 결과에 따라 압도적인 승리를 [166]거두면서 마린 르펜 국민전선 후보가 한 수 양보했습니다.[167] 39세에 그는 프랑스 역사상 최연소 대통령이 되었고 나폴레옹 이후 최연소 프랑스 국가 원수가 되었습니다.[168][169] 그는 또한 1958년 제5공화국이 수립된 후 태어난 프랑스의 첫 번째 대통령입니다.

마크롱은 5월 14일에 공식적으로 대통령이 되었습니다.[170] 그는 패트릭 스트르조다를 비서실장으로, 이스마 ë 에멜리엔을 전략, 커뮤니케이션 및 연설을 위한 특별 고문으로 임명했습니다. 5월 15일, 그는 공화당의 에두아르 필리프를 총리로 임명했습니다.[173][174] 같은 날, 그는 베를린에서 앙겔라 메르켈 독일 총리를 만나 첫 공식 외국 방문을 했습니다. 두 지도자는 유럽연합에 대한 프랑스-독일 관계의 중요성을 강조했습니다.[175] 그들은 유럽 연합 조약의 변경에 반대하지 않는다고 주장하면서 유럽을 위한 "공통 로드맵"을 작성하기로 합의했습니다.[176]

2017년 총선에서 마크롱의 정당인 라 레퓌블리크 앙마르슈와 민주운동 동맹들은 577석 중 350석을 차지하며 안정적인 과반을 확보했습니다.[177] 공화당이 상원 선거의 승자로 부상한 후, 크리스토프 카스타너 정부 대변인은 이번 선거가 자신의 당을 위한 "실패"라고 말했습니다.[178]

2020년 7월 3일, 마크롱은 중도우파 장 카스텍스를 프랑스 총리로 임명했습니다. 사회 보수주의자로 묘사되는 카스텍스는 공화당 소속이었습니다.[179] 그 임명은 "경제적인 측면에서 중도우파로 널리 알려진 코스를 두 배로 줄이는 것"이라고 묘사되었습니다.[180]

국내정책

마크롱은 대통령으로서 첫 몇 달 동안 공공 윤리, 노동법, 세금, 그리고 법 집행 기관의 권한에 대한 일련의 개혁안을 제정할 것을 압박했습니다.[citation needed]

반부패

페넬로페게이트에 대응하여 국회는 마크롱이 제안한 2017년 7월까지 프랑스 정치의 대량 부패를 중단하고 선출된 대표의 가족 고용을 금지하는 법안의 일부를 통과시켰습니다.[181] 한편, 지역구 기금을 폐지하는 법안의 제2부는 상원의 반대를 거쳐 표결이 예정되어 있었습니다.[182]

마크롱의 정부 내 공식적인 역할을 아내에게 주려는 계획은 비민주적인 것부터 비평가들이 그가 족벌주의에 맞서 싸우는 것에 대한 모순이라고 생각하는 것까지 다양한 비판들로 비난을 받았습니다.[183] change.org 에 거의 29만 명의 서명이 있는 온라인 청원 이후 마크롱은 그 계획을 포기했습니다. 지난 8월 9일, 국회는 마크롱 선거운동의 핵심 주제인 공직자윤리법을 지역구 기금 폐기와 관련한 토론을 거쳐 채택했습니다.[185]

노동정책과 노조

마크롱은 현재 프랑스 체제의 적대적 노선에서 벗어나 독일과 스칸디나비아를 모델로 한 보다 유연하고 합의 주도적인 체제로 노조-경영 관계를 전환하는 것을 목표로 하고 있습니다.[186][187] 그는 또한 동유럽에서 온 값싼 노동력을 고용하는 회사들과 그 대가로 프랑스 노동자들의 일자리에 영향을 미치는 것에 대해 행동하기로 약속했는데, 이것은 그가 "사회적 덤핑"이라고 말했습니다. 1996년 게시된 근로자 지침에 따라 동유럽 노동자들은 동유럽 국가에서 급여 수준으로 제한된 기간 동안 고용될 수 있으며, 이로 인해 EU 국가들 간의 분쟁이 발생했습니다.[188]

프랑스 정부는 마크롱과 그의 정부가 프랑스 경제에 활력을 불어넣기 위해 취한 첫 조치 중 하나인 프랑스의 노동 규칙("Code du Travail")에 대한 제안된 변경 사항을 발표했습니다.[189] 마크롱의 개혁 노력은 일부 프랑스 노동조합의 저항에 부딪혔습니다.[190] 최대 노동조합인 CFDT는 마크롱의 밀어붙이기에 유화적인 접근을 하며 대통령과 협상에 나섰고, 더 호전적인 CGT는 개혁에 더 적대적입니다.[186][187] 마크롱의 노동부 장관인 무리엘 페니코가 이 작업을 감독하고 있습니다.[191]

상원을 포함한 국회는 이 제안을 승인했고, 정부는 노조 및 사용자 단체와의 협상을 거쳐 노동법을 완화할 수 있게 되었습니다.[192] 노조와 논의한 이 개혁안은 부당하다고 판단되는 해고자에 대한 급여 지급을 제한하고, 회사들이 직원을 고용하고 해고할 수 있는 더 큰 자유와 허용 가능한 근로 조건을 규정할 수 있도록 했습니다. 대통령은 9월 22일 노동 규칙을 개혁하는 5개의 법령에 서명했습니다.[193] 2017년 10월에 발표된 정부 수치에 따르면 노동법 개혁 입법 추진 기간 동안 실업률은 2001년 이후 가장 큰 1.8% 감소했습니다.[194]

이주위기

2018년 1월 16일, 마크롱은 난민, 특히 칼레 정글에 대해 말하면서 이민과 망명에 대한 정부 정책을 설명하기 전에 파리에 또 다른 난민 캠프가 형성되는 것을 허용하지 않을 것이라고 말했습니다.[195] 그는 또한 망명 신청과 추방을 가속화하되 난민들에게 더 나은 주거를 제공할 계획을 발표했습니다.[196]

2018년 6월 23일 마크롱 대통령은 "유럽이 2015년에 경험한 것과 같은 규모의 이주 위기를 겪고 있지 않은 것이 현실"이라며 "이탈리아와 같은 나라는 지난해와 같은 이주 압력을 전혀 받고 있지 않습니다. 오늘날 유럽에서 우리가 겪고 있는 위기는 정치적 위기입니다."[197] 2019년 11월 마크롱은 새로운 이민 규칙을 도입하여 프랑스에 도착하는 난민의 수를 제한하는 동시에 이민 정책을 "통제권을 되찾겠다"고 밝혔습니다.[198]

경제정책

2017년 7월 19일, 당시 육군 총참모장이었던 피에르 드 빌리어즈는 마크롱과의 대립 끝에 사임했습니다.[199] 드 빌리어즈는 그가 물러나는 주된 이유로 8억 5천만 유로의 군 예산 삭감을 꼽았습니다. 르몽드는 나중에 드 빌리어즈가 국회의원 모임에서 "나는 내 자신이 이렇게 엉망이 되는 것을 내버려두지 않을 것이다"라고 말했다고 보도했습니다.[200] 마크롱은 드 빌리어즈의 후임으로 프랑수아 르콩트르를 지명했습니다.[201]

마크롱 정부는 9월 27일에 첫 번째 예산을 발표했는데, 그 조건은 EU의 재정 규칙에 따라 공공 적자를 가져오기 위해 세금과 지출을 줄였습니다.[202] 이 예산은 부동산을 대상으로 한 부유세를 대체해 부유세를 폐지하겠다는 마크롱의 대선 공약을 이행한 것입니다.[203] 교체되기 전에 세금은 세계 가치가 130만 유로를 초과하는 프랑스 거주자들의 재산의 1.5%까지 징수했습니다.[204]

2018년 2월, 마크롱은 프랑스 공무원에서 더 많은 일자리를 줄이기 위한 시도로 자발적인 중복을 제공하는 계획을 발표했습니다.[205]

2019년 12월, 마크롱은 20세기 연금 제도를 폐지하고 국가가 관리하는 단일 국민 연금 제도를 도입하겠다고 발표했습니다.[206] 2020년 1월, 마크롱은 새로운 연금 계획에 반대하는 몇 주간의 대중 교통 폐쇄와 파리 전역의 공공 기물 파손 사건 이후, 정년을 개정함으로써 그 계획에 타협했습니다.[207] 지난 2월 프랑스 헌법 제49조를 활용한 연금 개편이 법령으로 채택됐습니다.[208] 그러나 2020년 3월 16일 마크롱은 프랑스가 코로나19 확산을 늦추기 위해 봉쇄에 들어가면서 법안 초안이 철회될 것이라고 발표했습니다.[209]

테러

2017년 7월, 상원은 마크롱의 선거 공약인 더 엄격한 테러 방지법이 있는 논란이 많은 법안에 대한 첫 번째 읽기를 승인했습니다. 국회는 10월 3일 19명의 기권으로 법안 415 대 127을 통과시키기로 투표했습니다. 제라르 콜롱 내무장관은 투표를 앞두고 프랑스를 "아직 전쟁 상태"라고 표현했는데, 마르세유 10월 1일의 칼부림 사건은 이틀 전에 벌어졌습니다. 그 후 상원은 10월 18일 244 대 22의 차이로 두 번째 법안을 통과시켰습니다. 그날 오후 마크롱은 2017년 초부터 13건의 테러 계획이 실패했다고 말했습니다. 이 법은 프랑스의 비상사태를 대체하고 일부 조항을 영구적으로 만들었습니다.[210]

그 법안은 인권 옹호자들에 의해 비판을 받았습니다. 르 피가로의 여론조사에 따르면 62%의 응답자가 개인의 자유를 침해할 것이라고 생각했음에도 불구하고 57%가 찬성했습니다.[211]

이 법은 당국에게 집 수색, 이동 제한, 예배 장소 폐쇄,[212] 기차역과 국제 항구와 공항 주변 지역 수색 등의 권한을 확대해 줍니다. 시민의 자유에 대한 우려를 해소하기 위해 수정을 거쳐 통과되었습니다. 가장 징벌적인 조치는 매년 검토될 것이며 2020년 말까지 만료될 예정이었습니다.[213] 이 법안은 2017년 10월 30일 마크롱에 의해 법으로 서명되었습니다. 그는 11월 1일부터 비상사태를 종식시킬 것이라고 발표했습니다.[214]

민권

2018년 2월에 코르시카를 방문한 마크롱은 코르시카를 공용어로[215] 사용하는 코르시카 민족주의적 바람을 거부하면서도 프랑스 헌법에 코르시카를 인정하겠다고 제안하여 논란을 일으켰습니다.[216]

마크롱은 또한 프랑스에서 이슬람 종교를 "재편"하는 계획을 제안했습니다. "우리는 프랑스에서 이슬람의 구조화와 그것을 설명하는 방법에 대해 연구하고 있습니다. 매우 중요합니다. 제 목표는 라 ï시테의 중심에 있는 것, 믿지 않는 것으로 믿을 수 있는 가능성을 재발견하는 것입니다. 국민 통합과 자유로운 의식을 가질 수 있는 가능성을 보존하기 위해서입니다." 그는 그 계획에 대한 더 이상의 정보를 밝히기를 거부했습니다.[217]

외교정책과 국방

마크롱은 2017년 5월 25일에 열린 브뤼셀 정상회담에 참석했는데, 이는 프랑스 대통령으로서 첫 나토 정상회담이었습니다. 정상회담에서 도널드 트럼프 미국 대통령을 처음 만났습니다. 이번 만남은 '권력 다툼'으로 특징지어지는 두 사람의 악수로 널리 알려졌습니다.[218][219]

2017년 5월 29일, 마크롱은 베르사유 궁전에서 블라디미르 푸틴을 만났습니다. 이 회의는 마크롱이 러시아 투데이와 스푸트니크를 비난하면서 논란을 일으켰고, 이 통신사들은 "영향력과 선전, 거짓말 선전의 기관"이라고 비난했습니다.[220][221] 마크롱 대통령은 또 IS 격퇴전에 협력할 것을 촉구하고 화학무기를 사용할 경우 시리아에서 프랑스가 무력으로 대응할 것이라고 경고했습니다.[222] 마크롱은 2018년 시리아 두마에서 발생한 화학물질 공격에 대응해 미국, 영국과 공조해 프랑스가 시리아 정부 유적지 공습에 참여하도록 지시했습니다.[223][224]

마크롱 대통령은 29일 첫 주요 외교 정책 연설에서 국내외 이슬람 테러와 싸우는 것이 프랑스의 최우선 과제라고 말했습니다. 마크롱 대통령은 북한이 일본 상공에서 미사일을 발사한 당일, 북한을 압박해 협상에 나서도록 국제사회의 강경한 입장을 촉구했습니다. 또 이란 핵협상에 대한 지지를 확인하고 베네수엘라 정부를 "독재"라고 비판했습니다. 그는 오는 9월 독일 선거 이후 유럽연합의 미래에 대한 새로운 구상을 발표할 것이라고 덧붙였습니다.[225] 지난 2월 제56차 뮌헨안보회의에서 마크롱은 유럽연합 강화를 위한 10년 비전 정책을 발표했습니다. 마크롱은 더 큰 예산, 통합된 자본시장, 효과적인 국방정책, 신속한 의사결정이 유럽의 열쇠를 쥐고 있다고 말했습니다. 그는 나토, 특히 미국과 영국에 대한 의존도는 유럽에 좋지 않으며, 러시아와 대화를 구축해야 한다고 덧붙였습니다.[226]

프랑스 비아리츠에서 열린 제45차 G7 정상회의에 앞서 마크롱은 "러시아는 완전히 가치 있는 유럽 안에 속해 있다"며 블라디미르 푸틴 대통령을 브레간송 요새에서 주최했습니다.[227] 마크롱 대통령은 정상회담 자체에서 자바드 자리프 이란 외무장관의 초청을 받아 여백에 앉았습니다.[clarification needed] "고위험 외교적 도박을 시도했다"는 마크롱은 최근 이슬람 공화국과 미국과 영국 사이의 긴장이 고조되고 있음에도 불구하고 이란 외무장관이 이란 핵 프로그램을 둘러싼 긴장된 상황을 완화할 수 있을 것이라고 생각했습니다.[228]

2019년 3월, 중국과 미국의 경제 관계가 무역 전쟁이 진행 중인 상황에서, 마크롱과 중국 지도자 시진핑은 수년에 걸쳐 많은 부문을 포괄하는 총 400억 유로(450억 달러)에 달하는 15개의 대규모 무역 및 비즈니스 협정에 서명했습니다.[229] 여기에는 에어버스로부터 300억 유로의 비행기 구매가 포함되었습니다. 새로운 무역 협정은 항공을 넘어 프랑스가 중국에 건설한 해상 풍력 발전소, 프랑스-중국 협력 기금, BNP 파리바와 중국 은행 간 수십억 유로의 공동 자금 조달뿐만 아니라 프랑스 수출도 포함했습니다. 다른 계획에는 새로운 선박 건조뿐만 아니라 중국 공장의 현대화에 수십억 유로가 투입될 예정입니다.[230]

마크롱은 2020년 7월 "(EU) 회원국의 해양 공간이 침해되고 위협받는 것은 용납할 수 없다"며 그리스와 키프로스의 주권을 침해한 튀르키예에 대한 제재를 촉구했습니다. 리비아에 대한 터키의 군사 개입도 비판했습니다.[232][233] 마크롱은 "우리는 나토 회원국이라는 점에서 러시아보다 튀르키예에 더 많은 것을 기대할 권리가 있다"고 말했습니다.

2021년 마크롱은 북아일랜드 의정서 이행에 대한 보리스 존슨 영국 총리와의 분쟁 이후 북아일랜드가 진정한 영국의 일부가 아니라고 말한 것으로 보도되었습니다.[235] 그는 이후 영국이 아일랜드해 국경을 참조해 해상으로 북아일랜드와 분리돼 있다는 사실을 언급한 것이라며 이를 부인했습니다.[236][237]

2021년 9월, 미국, 영국, 호주 간의 AUKUS 안보 협정의 여파로 인해 프랑스-미국 관계가 긴장되었습니다. 이 안보 협정은 인도-태평양 지역에서 중국의 힘에 대항하기 위한 것입니다. 그 합의의 일환으로, 미국은 호주에 핵 추진 잠수함을 제공하기로 합의했습니다. 호주 정부는 AUKUS 가입 후 프랑스와 맺은 재래식 동력 잠수함 제공 협정을 취소해 프랑스 정부를 분노케 했습니다.[238] 9월 17일, 프랑스는 호주와 미국의 자국 대사들을 소환하여 협의를 하였습니다.[239] 프랑스는 과거의 긴장에도 불구하고 미국 주재 대사를 철수시킨 적이 없었습니다.[240] 마크롱 대통령과 조 바이든 미국 대통령이 후자의 요청으로 통화한 뒤, 두 정상은 양국 긴장을 완화하기로 합의했고, 백악관은 동맹국 간 열린 협의가 있었다면 위기를 피할 수 있었을 것이라고 인정했습니다.[241][242][unreliable source?]

2021년 11월 26일, 마크롱과 이탈리아 총리 마리오 드라기는 로마 퀴리날 궁전에서 퀴리날 조약에 서명했습니다.[243] 이 조약은 유럽 및 외교 정책, 안보 및 국방, 이주 정책, 경제, 교육, 연구, 문화 및 국경 간 협력 문제에 있어 프랑스와 이탈리아의 입장을 수렴하고 조정하는 것을 목표로 했습니다.[244]

2022년 러시아의 우크라이나 침공의 서막에서 마크롱은 블라디미르 푸틴 러시아 대통령과 직접 얼굴을 맞대고 전화 통화를 했습니다.[245] 러시아 침공이 시작된 지 거의 두 달이 지난 마크롱 대통령의 재선 캠페인 기간 동안 마크롱 대통령은 유럽 지도자들에게 푸틴 대통령과의 대화를 유지할 것을 요구했습니다.[246]

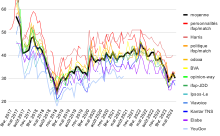

지지율

르 저널 뒤 디망슈(Le Journal du Dimanche)의 IFOP 여론조사에 따르면 마크롱은 6월 24일까지 64%로 [247][248]상승한 62%의 지지율로 5년 임기를 시작했습니다.[249] 한 달 뒤 마크롱은 1995년 자크 시라크 이후 역대 대통령 중 임기 초반 최대인 10%포인트의 지지율 하락을 겪었고, 8월까지 6월 이후 24%포인트의 지지율 하락을 보였습니다.[250] 이는 최근 피에르 드 빌리에르 전 국방장관과의 대립,[251] 파산한 STX 오프쇼어앤조선이 소유한 샹티에 드 아틀란티크 조선소의 국유화,[252] 주거급여 감소 등이 원인으로 꼽혔습니다.[253]

2017년 9월 말까지 응답자 10명 중 7명은 에마뉘엘 마크롱이 그의 선거 공약을 존중한다고 믿었다고 답했지만,[254][255] 대다수는 정부가 내세운 정책이 "부당하다"고 생각했습니다.[256] 마크롱의 인기는 2018년 다시 급격히 떨어져 노란 조끼 운동 당시인 11월 말까지 약 25%에 달했습니다.[257][unreliable source?] 프랑스의 코로나19 팬데믹 기간 동안 그의 인기는 증가하여 2020년 7월에 최고치인 50%에 달했습니다.[258][259]

베날라 사건

2018년 7월 18일, 르몽드는 기사에서 마크롱의 직원 알렉상드르 베날라가 올해 초 파리에서 5월 1일 시위 도중 경찰 행세를 하고 시위자를 구타했으며 15일 동안 정직 처분을 받은 후 내부적으로 강등되었다고 밝혔습니다. 엘리제는 사건을 검찰에 회부하지 못하였고, 기사가 게재된 다음 날까지도 사건에 대한 예비조사를 개시하지 못하였는바, 그리고 베날라가 제공한 관대한 처벌은 야당 내에서 행정부가 형사소송법에 따라 요구된 대로 검사에게 알리지 않기로 의도적으로 선택한 것이 아닌지에 대한 의문을 제기했습니다.[260]

2022년 대통령 선거운동

2022년 선거에서 마크롱은 2002년 선거에서 자크 시라크가 장마리 르펜을 꺾은 이후 현직자로는 처음으로 재선에 성공했습니다.[261] 마크롱 후보는 결선투표에서 마린 르펜 후보를 이번에도 58.55%의 득표율로 41.45%[262]를 기록하며 근소한 차이로 이겼습니다. 거의 기록적인 기권으로 인해 이는 등록 유권자의 38.52%를 차지했으며, 1969년 조르주 퐁피두의 37.5% 이후 가장 낮은 수치입니다.[263] 프랑스 극우파는 국민당 후보(르펜, 제무르, 뒤퐁-아이그낭)가 1차 투표에서 32.3%, 르펜이 2차 투표에서 41.5%의 기록적인 득표율을 달성하며 프랑스 공화국 출범 이후 가장 높은 득표율을 기록했습니다.[citation needed]

연임

마크롱의 두 번째 취임식은 2022년 5월 7일에 열렸지만, 그의 두 번째 대통령 임기는 2022년 5월 14일에 공식적으로 시작되었습니다.

부담정부

2022년 5월 16일, 장 카스텍스 총리는 22개월 만에 정부 수반직을 사임했습니다. 같은 날 마크롱 대통령은 호텔 마티뇽에서 엘리자베스 보른을 임명하여 1991년부터 1992년 사이에 에디스 크레송에 이어 프랑스 역사상 두 번째 여성 총리가 되었습니다. 그리고 2022년 5월 20일 새 정부를 수립했습니다.

2022년 6월 국회의원 선거

그의 두 번째 임기 한 달이 지난 2022년 6월, EU 이사회의 프랑스 대통령직이 끝나기 2주도 채 남지 않았고, 그가 논란이 된 '타맥 연설'에서 유권자들에게 '탄탄한 다수'를 넘겨달라고 요구한 지 며칠 지나지 않아,[264] 마크롱은 2022년 국회의원 선거에서 다수당을 잃고 헝 의회로 복귀했습니다.[265] 115석의 과반이 선거에 들어간 마크롱의 대통령 연합은 국회에서 전체 과반을 차지하는 데 필요한 289석의 문턱에 도달하지 못해, 지난 의회에서 열린 346석 중 251석만 유지했고, 절대 다수에는 38석이 미치지 못했습니다.[266] 결정적으로, 마크롱 대통령의 가까운 세 명의 정치적인 동맹들은 선거에서 패배했습니다: 현직 국회의원 리처드 페랜드, 마크롱의 LREM 의회 당 대표 Christophe Castaner, 그리고 MoDem 의회 그룹 대표 Patrick Mignola. 따라서 마크롱의 의회 블록 지도력을 사실상 '참수'시키고, 굶주린 의회 영토에서 대통령의 정치적 입지를 더욱 약화시킵니다.[267]

저스틴 베냉(해양부 차관), 브리짓 부르기뇽(보건예방부 장관), 아멜리 드 몽찰린(생태전환부 장관) 등 3명의 정부 장관이 자리를 잃고 사임했습니다.[268]

여전히 엘리자베스 보른 총리가 이끄는 마크롱 정부는 안정적인 다수 정부 구성을 위한 야당 지도자들과의 대화가 실패한 후 2022년 7월 초에 개편되어 소수 정부로 계속되었습니다.[269]

가사

마크롱의 두 번째 대통령 임기는 두 가지 중요한 정치적 논란으로 시작됐습니다. 보른 새 내각이 발표된 지 몇 시간 만에 새로 부임한 데미안 아바드 연대부 장관에 대한 강간 혐의가 공개됐고,[270] 지난 5월 28일 생드니의 스타드 드 프랑스에서 열린 2022 UEFA 챔피언스리그 결승전 대란의 처리는 국내외의 비난을 받았습니다.[271]

2022년 입법 선거 이후 입법부 내 소수 지위에도 불구하고 마크롱 정부는 생계비 위기를 [272]완화하고 코로나 시대의 "건강 비상사태"를 폐지하며 프랑스 원자력 [273]부문을 부활시키는 법안을 통과시켰습니다.[274] 그러나 정부안은[275] 국회에서 여러 차례 부결되었고 2022년 말까지 부담 내각은 2023년 정부예산안과 사회보장예산안을 통과시키기 위해 헌법 49.3조의 규정을 10회 연속으로 사용해야 했습니다.[276]

연금개혁

2023년 3월, 마크롱 정부는 은퇴 연령을 62세에서 64세로 올리는 법안을 통과시켰는데, 의회 교착 상태를 타개하기 위해 49.3조에 다시 의존함으로써 부분적으로 의회를 우회했습니다.[277] 지난 1월 법안이 발의되면서 시작된 전국적인 시위는 엄숙한 표결 없이 통과된 이후 더욱 거세졌습니다.[citation needed][clarification needed]

본 정부 불신임 투표

2023년 3월 20일, 보른 총리가 이끄는 마크롱 내각은 당을 초월한 불신임안에서 겨우 9표 차이로 살아남았는데, 이는 1992년 이래로 가장 적은 표 차이입니다.[278]

2023년 6월 12일, 그의 정부는 제16대 의회가 시작된 이래 17번째 불신임안에서 살아남았고, 좌파 NUPES 연합이 제기한 이 동의안은 필요한 289표에 50표가 모자랐습니다.[279]

나헬 메르주크 폭동

2023년 초여름, 프랑스 당국은 17세의 나헬 M을 교통 정차 중 경찰관에 의해 살해한 후 폭동에 직면했습니다.[280][281] 2005년 프랑스 폭동에[citation needed] 버금가는 강도로 광범위한 불안을 진정시키기 위해, 마크롱 행정부는 정부의 대응을 강화했고, 총 45,000명의 경찰관들이 현장에 배치되었고, 법원에 더 가혹한 선고와 신속한 절차를 적용하도록 권고하는 장관 명령이 있었습니다:[282] 이 단속은 1건 이상의 결과를 낳았습니다.소요사태가 발생한 지 4일째 되는 날 밤에만 300명이 체포되어 폭동이 시작된 이래 총 체포자 수는 7월 1일 현재 2,000명을 넘어섰습니다.[283]

2023년 정부 개각

2023년 7월 20일 마크롱은 연금 제도 개혁 통과를 둘러싼 격렬한 시위에 이어 2023년 4월 자신이 요구한 "100일간의 유화와 행동"이 끝날 때 정부 개편을 단행했습니다. 파프 은디아예와 말렌 시아파는 개각의 일환으로 해임되었습니다.[284]

국방정책

마크롱은 2023년 7월 13일 프랑스 의회에서 통과된 후, 2024년에서 2030년 사이에 총 4,130억 유로로 군사비 지출이 40% 증가할 수 있는 발판을 마련하는 다년간의 군사 계획 법안에 서명했습니다.[285][286]

이민정책

2023년 2월, 마크롱 정부는 추방 안전 장치를 제거하고 망명 신청 절차와 이민 소송을 빠르게 추적하는 동시에 미등록 노동자의 합법화를 촉진하는 것을 목표로 하는 이민 및 망명 법안을 도입했습니다.[287] 그의 정부는 이후 의회에서 패배할 것이라는 우려 속에 법안 초안을 철회하고 대신 중도우파인 LR당과 회담을 가진 뒤 가을에 법안을 재도입할 계획입니다.[288]

마크롱은 2023년 8월 주간지 르 포인트와의 장문의 인터뷰에서 프랑스가 "현재 상황이 지속 가능하지 않기 때문에 불법 이민을 시작으로 이민을 대폭 줄여야 한다"고 말했습니다.[289]

2023년 12월 11일, 마크롱 정부가 발의한 '플래그십' 이민법안이 국회에서 예비해임동의안이 간발의 차로 통과되면서 뜻밖에도 무산됐습니다.[290] 정치 평론가들과 뉴스 매체들은 이번 투표가 "경이로운 대실패"라고 표현했고, 결국 마크롱 소수 정부에 큰 정치적 위기를 불러 일으켰습니다.[291]

그 법안을 살리기 위한 노력으로, 마크롱의 정부는 그 법안 초안을 공동 의회 위원회에 보냈습니다: 그것은 급격하게 강화된 법안에 대해 보수적으로 통제되는 상원과 거래하는 결과를 낳았습니다. 2023년 12월 19일, 프랑스 의회는 보수적인 LR 및 극우 RN 의회 그룹의 지지와 마크롱 자신의 연합 및 장관들의 큰 반란에도 불구하고 법안을 통과시켰습니다.[292] 마크롱이 불과 6개월 전에 정부에 임명했던 오렐리앙 루소 보건부 장관은 투표 직후 사임했습니다.[293]

헌법개혁

2023년 10월 4일 프랑스 헌법 65주년 기념일에 마크롱은 헌법 개혁을 위한 길을 공개했습니다: 국민투표의 범위를 넓히고 규칙을 완화하는 것; 낙태와 기후 보호에 대한 권리를 헌법에 명시하는 것; 영토 발전의 수준을 높이는 것; 코르시카와 뉴칼레도니아에 어떤 형태로든 정치적 자치권을 부여하는 것.[294]

구체화를 위해서라면 마크롱 대통령이 지난 2017년 취임한 이후 의회에서 실패한 이후 첫 개헌이 될 것으로 보입니다.

아탈 정부

2024년 1월, '논란의 여지가 있는' 이민 법안 통과로 빚어진 정부 위기를 계기로 마크롱은 엘리자베스 보른 총리의 사임을 요청했고, 이후 그녀를 가브리엘 아탈 교육부 장관으로 교체했습니다. 그를 프랑스 역사상 최연소 정부 수반이자 공개적으로 동성애자로 만든 최초의 인물로 만들었습니다.[295]

새로운 아탈 내각은 마크롱 대통령 취임 이후 가장 우경화된 정부로 널리 묘사되었습니다. 마크롱과 아탈이 2024년 1월 11일 임명한 14명의 각료 중 57%가 보수 성향의 UMP/LR 당 출신이며, 퇴임하는 보른 정부의 저명한 좌파 장관들은 해임되었습니다. 오른쪽으로 눈에 띄는 기울기를 나타내는 것으로 설명된 움직임.[296][297]

대외업무

2022년 6월 16일, 마크롱은 독일 총리 올라프 숄츠, 이탈리아 총리 마리오 드라기와 함께 우크라이나를 방문했습니다. 그는 볼로디미르 젤렌스키 우크라이나 대통령을 만나 우크라이나에 대해 "유럽의 통합"을 표명했습니다.[298][299] 그는 러시아-우크라이나 전쟁에서 중립을 지키던 국가들이 역사적인 실수를 저질렀고, 새로운 제국주의에 연루되었다고 말했습니다.[300]

2022년 9월 마크롱은 미국, 노르웨이 및 기타 "친선" 천연가스 공급국이 극도로 높은 공급 가격에 대해 비판하면서 2022년 10월 유럽인들이 "당신이 산업에 판매하는 가격보다 4배 더 많은 비용을 지불하고 있다"[301]고 말했습니다. 그것이 바로 우정의 의미는 아닙니다."[302]

마크롱과 그의 부인은 2022년 9월 19일 런던 웨스트민스터 사원에서 열린 엘리자베스 2세 여왕의 국장과 찰스 3세의 대관식에 참석했습니다.[303][304]

2022년 10월 23일, 마크롱은 그녀와 그녀의 장관들이 취임 선서를 한 지 하루 만에 새로운 이탈리아 총리 조르지아 멜로니를 만난 첫 외국 지도자가 되었습니다.[305]

중국 공산당 총서기이자 중국 국가주석인 시진핑을 공식 면담한 우르술라 폰데어라이엔 유럽연합 집행위원장과의 중국 정상회담에서 마크롱 대통령은 유럽이 전반적으로 미국에 대한 의존도를 줄이고 중립을 지키며 대만을 둘러싼 미국과 중국의 대립 가능성에 말려들지 말 것을 주문했습니다. 마크롱 대통령은 3일간의 중국 국빈 방문 후 연설에서 유럽이 '제3의 초강대국'이 될 수 있음을 시사하며 전략적 자치론을 강조했습니다. 그는 헤이그에서 열린 후속 연설에서 유럽의 전략적 자율성에 대한 자신의 비전을 더욱 구체화하기 위해 유럽이 자국의 방위산업을 활성화하는 데 주력하고, 추가적으로 미국 달러(USD)에 대한 의존도를 줄여야 한다고 주장했습니다.[306][307] 2023년 6월 7일 범유럽 싱크탱크인 유럽 외교위원회(ECFR)의 보고서에 따르면 대부분의 유럽인들은 중국과 미국에 대한 마크롱의 견해에 동의하는 것으로 나타났습니다.[308]

2023년 2월, 그는 파리에서 에티오피아 정부와 티그레이 반군 간의 티그레이 전쟁으로 경색된 프랑스와 에티오피아의 관계 정상화를 위해 아비 아머드 에티오피아 총리를 환영했습니다.[309]

2023년 5월 31일 마크롱은 브라티슬라바에서 열린 GLOBSEC 포럼을 방문하여 유럽 주권에 대한 연설을 다시 했습니다.[310] 브라티슬라바 연설에 이어진 질의응답 [311]시간에 그는 푸틴 대통령과의 협상이 젤렌스키를 포함한 다른 사람들이 보고 싶어하는 어떤 전범 재판소보다 우선해야 할 수도 있다고 말했습니다.[312]

2023년 6월 12일, 마크롱은 러시아가 점령한 우크라이나 남동부를 해방시키기 위해 진행 중인 반격에 우크라이나군을 돕기 위해 더 많은 탄약, 무기, 무장 차량을 전달하겠다고 약속했습니다.[313] 빌뉴스에서 열린 북대서양조약기구(NATO·나토) 정상회의에서 그는 전선 깊숙이 있는 러시아 목표물을 타격하기 위해 우크라이나에 스칼프 장거리 순항미사일을 공급하겠다고 약속했습니다.[314] 2023년 11월 10일, 그는 러시아가 우크라이나에서 하고 있는 일은 "제국주의와 식민주의"이며, 우크라이나가 스스로를 방어할 수 있도록 돕는 것이 프랑스와 다른 나라들의 "의무"라고 말했지만, 아마도 러시아와 공정한 평화 협상을 하고 해결책을 찾아야 할 때가 올 것이라고 덧붙였습니다.[315]

2023년 6월 마크롱은 많은 사람들이 새로운 브레튼 우즈 회의라고 묘사하는 세계 기후 금융 회의를 주최했습니다. 그 목적은 세계 경제를 기후 변화와 기아라는 동시대적인 위협에 맞춰 조정하는 것입니다. 그 제안 중 하나는 저소득 국가들이 부채 상환 대신 기후 변화와 빈곤을 막는 데 그들의 자원을 사용할 수 있도록 크레딧 대신 도움을 제공하는 것입니다. 마크롱은 이 아이디어를 지지했지만 우간다의 한 기후 활동가는 마크롱이 기후와 4천만 명의 식수에 큰 위협이 되는 동아프리카 원유 수송관과 같은 프로젝트를 동시에 지지한다면 그 약속들은 무의미하다고 말했습니다.[316] 마크롱 대통령은 정상회담에서 국제적인 세제와 채무 재조정을 제안하면서도 국제적인 협력이 있어야만 효과를 볼 수 있다고 강조했습니다.[317]

2023년 7월, 마크롱은 계속되는 나헬 M. 폭동 때문에 계획된 독일 국빈 방문을 연기했습니다.[318]

2023년 10월 마크롱은 이스라엘-하마스 전쟁 중 하마스의 행동을 비난하고 이스라엘과 이스라엘의 자위권에 대한 지지를 표명했습니다.[319][320] 그는 하마스를 지지하는 이란을 비난했습니다.[321] 10월 24일, 마크롱은 이스라엘과의 연대를 표현하기 위해 이스라엘을 방문했습니다. 그는 반 ISIL 연합군도 하마스와 맞서 싸워야 한다고 말했습니다.[322] 2023년 11월 10일, 그는 휴전을 요구하며 이스라엘에게 가자 폭격과 민간인 살해를 중단할 것을 촉구했습니다.[323]

논란

우버 파일

2022년 7월 10일, 가디언지는 마크롱이 경제산업부 장관으로 재임하는 동안 우버의 로비를 도왔다고 폭로하면서 [324]야당 의원들의 의회 조사 요구가 이어졌습니다.[325][326] 마크롱은 자신의 변호에서 "할 일을 했다"며 "내일과 모레 다시 할 것"이라고 밝혔습니다.[326] 그는 "나는 그것이 자랑스럽다"[326]고 말했습니다.

정치적 입장

안도라 공국

프랑스의 대통령으로서 마크롱은 안도라의 두 공동 왕자들 중 한 명으로 직권상정하기도 합니다. 그의 비서실장인 Patrick Strzoda가 이 자격으로 그의 대표 역할을 합니다. 2003년 5월 12일, 현 우르젤 주교로 임명된 호안 엔릭 비베시스 시칠리아(Joan Enric Vivesis Sicilia)는 마크롱의 공동 왕자로 활동하고 있습니다. 마크롱은 2017년 6월 15일 카사 데 라 발에서 열린 법안에서 스트르조다를 통해 안도라 헌법을 맹세했습니다.[327]

코로나19 대유행 당시 안도라 정부는 프랑스에 경제 지원을 요청했지만 마크롱은 프랑스 은행이 유럽중앙은행의 승인 없이는 다른 나라에 대출을 제공할 수 없다며 거부했습니다.[328]

개인생활

마크롱은 24살 연하의 [329]브리짓 트로뉴와 [330]아미앵에 있는 전 라프로비던스 고등학교 교사와 결혼했습니다.[331][332] 그들은 그가 15세 학생이었을 때 그녀가 하고 있던 연극 워크숍에서 만났고 그녀는 39세의 선생님이었습니다. 그의 부모님은 그의 어린 시절이 이 관계를 부적절하게 만들었다고 생각했기 때문에, 그를 학교의 마지막 해를 마치기 위해 파리로 보내면서 그 부부를 떼어놓으려고 했습니다.[14][334] 이 커플은 마크롱이 졸업한 후 재회했고, 2007년에 결혼했습니다.[334] 그녀에게는 이전 결혼에서 얻은 세 자녀가 있습니다. 그에게는 자신의 자녀가 없습니다.[335][unreliable source?] 마크롱의 2017년 대선 캠페인에서 트로뉴의 역할은 마크롱의 가까운 동맹국들이 트로뉴가 대중 연설과 같은 기술을 개발하는 데 도움을 주었다고 언급하면서 중추적인 것으로 여겨졌습니다.[336]

그의 절친한 친구는 앙리 에르망(Henry Hermand, 1924–2016)으로, 마크롱이 재무 감사관으로 있을 때 파리에 있는 그의 첫 번째 아파트를 구입하기 위해 55만 유로를 빌려준 사업가입니다. 에르망은 또한 마크롱이 앙마르슈 운동을 위해 파리의 샹젤리제 거리에 있는 자신의 사무실 일부를 사용하도록 허락했습니다.[337][338]

2002년 프랑스 대선에서 마크롱은 진정한 보수주의자 장 피에르 셰브너먼트에게 표를 던졌습니다.[339] 2007년 마크롱은 대선 2라운드에서 세골렌 루아얄 후보에게 투표했습니다.[340] 2011년 사회당 예비선거에서 마크롱은 프랑수아 올랑드에 대한 지지의 목소리를 높였습니다.[341]

마크롱은 피아노를 연주하고,[342] 젊은 시절에 10년 동안 피아노를 공부했습니다.[15] 그는 특히 로베르트 슈만과 프란츠 리스트의 작품을 즐깁니다.[343][344] 마크롱은 또한 스키를 [345]타고 테니스를[346] 치고 복싱을 즐깁니다.[347] 마크롱은 모국어인 프랑스어 외에도 유창한 영어를 구사합니다.[348][349]

2017년 8월에는 한 사진기자가 마크롱이 마르세유에서 휴가를 보내고 있던 사저에 들어갔다가 경찰에 체포돼 6시간 동안 구금되기도 했습니다.[350] 마크롱은 그 후에 "괴롭힘"을 고발했습니다.[350] 2017년 9월, 그는 "회유의 표시로" 고소를 취하했습니다.[351]

2017년 8월 27일 마크롱과 그의 아내 브리지트는 엘리제 궁전에서 함께 살고 있는 검은 래브라도 리트리버-그리폰 개 니모를 입양했습니다.[352] 학창시절 마크롱은 가톨릭 신자로서 세례를 받기로 결심했습니다. 프란치스코 교황을 만나기 전인 2018년 6월, 그는 자신을 불가지론자 가톨릭 신자라고 밝혔습니다.[353][354] 같은 해 그는 로마의 대성당인 성 요한 라테란의 명예 교회가 되는 것에 동의했습니다.[354]

축구 팬인 마크롱은 프랑스 클럽 올랭피크 드 마르세유의 후원자입니다.[355] 2018년 월드컵 당시 필리프 벨기에 국왕, 마틸드 여왕과 함께 프랑스와 벨기에의 준결승전에 참석했고,[356] 크로아티아와의 월드컵 결승전에서는 콜린다 그라바르 키타로비치 크로아티아 대통령과 나란히 앉아 축하했습니다. 마크롱은 그의 축하 행사와 크로아티아 대통령과의 교류로 대중의 관심을 받았습니다.[357][358][359][360][361]

2020년 12월 17일 마크롱은 코로나19 양성[362] 반응을 보여 레바논 방문을 포함한 다음 달 예정된 여행을 취소했습니다.[363]

훈장과 훈장

국민훈장

| 리본바 | 명예. | 날짜 및 코멘트 |

|---|---|---|

| 국민훈장 그랜드 마스터 & 그랜드 크로스 | 2017년 5월 14일 – 대통령 취임 시 자동으로 실행 | |

| 국민훈장 그랜드 마스터 & 그랜드 크로스 | 2017년 5월 14일 – 대통령 취임 시 자동으로 실행 |

외국의 명예

프랑스 공화국의 대통령으로서

| 리본바 | 나라 | 명예. | 날짜. |

|---|---|---|---|

| 세라핌 기사단 | 2024년[364] 1월 30일 | ||

| 명예 기사 대십자가 | 2023년[365] 9월 20일 | ||

| 네덜란드 사자 기사단 대십자장 | 2023년4월11일[366][367] | ||

| 자이드 기사단의 칼라 | 2022년[368] 7월 18일 | ||

| 이탈리아 공화국 훈장 칼라를 단 기사 대십자장 | 2021년[369] 7월 1일 | ||

| 무공훈장 최고사령관 | 2020년[370][failed verification] 12월 8일 | ||

| 나일강 기사단의 칼라 | 2020년[371] 12월 7일 | ||

| 코트디부아르 국민훈장 그랜드 크로스 | 2019년[370] 12월 20일 | ||

| 레오폴트 훈장 그랜드 코돈 | 2018년11월19일[370] | ||

| 무궁화 대훈장 | 2018년[372] 10월 8일 | ||

| 칼라가 달린 백장미 기사단 대십자장 | 2018년[373] 8월 29일 | ||

| 코끼리 기사단 | 2018년[374] 8월 28일 | ||

| 나소 왕가 금사자 기사 | 2018년[370] 3월 19일 | ||

| 사자국훈장 대십자장 | 2018년[370] 2월 2일 | ||

| 튀니지 공화국 훈장 그랜드 코돈 | 2018년[375] 1월 31일 | ||

| 무공훈장 대십자장 | 2017년[370] 9월 22일 | ||

| 구국훈장 대십자장 | 2017년[376] 9월 7일 |

그의 대통령직 이전에

| 리본바 | 나라 | 명예. | 날짜. |

|---|---|---|---|

| 아즈텍 독수리 기사단의 띠 | 2016년[377] 9월 22일 | ||

| 대영 제국 훈장 명예 사령관 | 2014년[378] 6월 5일 | ||

| 남십자훈장 대감 | 2012년[379] 12월 9일 |

상

- 르 트롬비노스코프 (2014,2016)

- 샤를마뉴상 (2018)

- 지구 챔피언 (2018)

- Westfälischer Friedenspreis (2024)[380]

출판물

- Macron, Emmanuel; Goldberg, Jonathan; Scott, Juliette (2017). Revolution. Brunswick, Victoria, Australia: Scribe Publications. ISBN 978-1-925322-71-2. OCLC 992124322.

- ——; Fottorino, Éric (2017). Macron par Macron (in French). La Tour d'Aigues, France: Editions de l'Aube. ISBN 978-2-8159-2484-9. OCLC 1003593124.

메모들

- ^ 전관예우

참고문헌

- ^ "Dans un livre, Anne Fulda raconte Macron côté intime" (in French). JDD à la Une. 21 April 2017. Archived from the original on 19 May 2017. Retrieved 25 April 2017.

- ^ Badeau, Kevin (7 April 2017). "Le livre qui raconte l'intimité d'Emmanuel Macron". Les Echos. Archived from the original on 19 March 2018. Retrieved 20 May 2017.

- ^ "Qui sont le frère et la sœur d'Emmanuel Macron? – Gala". Gala.fr (in French). Archived from the original on 16 May 2017. Retrieved 6 August 2017.

- ^ Boucher, Laurent (26 April 2017). "Sur les traces de l'arrière-grand-père d'Emmanuel Macron entre Amiens et Arras". La Voix. Archived from the original on 2 July 2018. Retrieved 6 August 2017.

- ^ "Le Big Mac: Emmanuel Macron's Rise and Rise" 2020년 10월 27일 웨이백 머신(Wayback Machine)에 보관.

- ^ Flandrin, Antoine (16 September 2017). "L'histoire de France selon Macron". Le Monde. Archived from the original on 5 August 2020. Retrieved 21 December 2017.

- ^ "Sacrées mémés de Bagnères-de-Bigorre !". ladepeche.fr (in French). Archived from the original on 6 August 2017. Retrieved 6 August 2017.

- ^ "Emmanuel Macron en meeting à Pau devant 5 500 personnes". SudOuest.fr. Archived from the original on 6 August 2017. Retrieved 6 August 2017.

- ^ "Emmanuel Macron, l'Elysée pied au plancher". Libération (in French). Archived from the original on 14 July 2017. Retrieved 6 August 2017.

- ^ "D'où vient Emmanuel Macron ?". Les Échos. France. 24 April 2017. Archived from the original on 6 August 2017. Retrieved 6 August 2017.

- ^ Gorce, Bernard (10 April 2017). "La jeunesse très catholique des candidats à la présidentielle". La Croix. Archived from the original on 12 May 2017. Retrieved 7 May 2017.

- ^ a b 2017년 5월 9일 갈라 프랑스 웨이백 머신에 보관된 "엠마뉴엘 마크롱". 2017년 3월 3일 회수.

- ^ a b "Emmanuel Macron, un ex-banquier touche-à-tout à Bercy" (in French). France 24. 27 August 2014. Archived from the original on 15 March 2017. Retrieved 24 April 2017.

- ^ a b Chrisafis, Angelique (11 July 2016). "Will France's young economy minister – with a volunteer army – launch presidential bid?". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 26 July 2018. Retrieved 27 January 2017.

- ^ a b 88음표 pour piano solo, Jean-Pierre Thiollet, Neva Editions, 2015, p.193. ISBN 978-2-3505-5192-0

- ^ "What Emmanuel Macron's home town says about him". The Economist. 4 May 2017. Archived from the original on 4 May 2017. Retrieved 5 May 2017.

- ^ Vincent de Feligond, Emmanuel Macron, ancien consensiller du prince aux manetes de Bercy, 2017년 8월 3일 La Croix, Wayback Machine에서 아카이브됨, 2014년 8월 26일

- ^ 크리스틴 모닌, 레트로: 에마뉘엘 마크롱, 몽코팡 2017년 7월 12일 르 파리지앵 (프랑스어) 웨이백 머신에서 보관됨.

- ^ Jordan Grevet "엠마누엘 마크롱, 장관님은 훌륭하지 않습니다.."2017년 3월 27일, 클로저(프랑스어)의 웨이백 머신(Wayback Machine)에서 보관, 2014년 10월 13일.

- ^ De Jaeger, Jean-Marc (15 May 2017). "L'université de Nanterre félicite Emmanuel Macron, son ancien étudiant en philosophie". Le Figaro. Archived from the original on 19 May 2017. Retrieved 17 May 2017.

- ^ a b Guélaud, Claire (16 May 2012). "Emmanuel Macron, un banquier d'affaires nommé secrétaire général adjoint de l'Elysée". Le Monde (in French). Archived from the original on 3 August 2017. Retrieved 29 April 2017.

- ^ Wüpper, Gesche (27 August 2014). "Junger Wirtschaftsminister darf Frankreich verführen". Die Welt (in German). Archived from the original on 3 January 2017. Retrieved 29 April 2017.

- ^ "Emmanuel Macron, de la philosophie au ministère de l'Économie • Brèves, Emmanuel Macron, Paul Ricoeur, Politique, Socialisme, Libéralisme, François Hollande • Philosophie magazine". philomag.com (in French). 27 August 2014. Archived from the original on 6 August 2017. Retrieved 6 August 2017.

- ^ "Emmanuel Macron, premier Président qui n'a pas fait son service militaire". L'Opinion (in French). 9 May 2017. Archived from the original on 6 August 2017. Retrieved 6 August 2017.

- ^ Chrisafis, Angelique (19 July 2017). "Head of French military quits after row with Emmanuel Macron". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 21 July 2017. Retrieved 22 July 2017.

- ^ "Emmanuel Macron, le coup droit de Hollande – JeuneAfrique.com". JeuneAfrique.com (in French). 3 March 2015. Archived from the original on 27 March 2016. Retrieved 6 August 2017.

- ^ a b Kaplan, Renée (2 September 2014). "Who is the hot new French Economy Minister". Frenchly. Archived from the original on 9 September 2016. Retrieved 14 April 2017.

- ^ Coignard, Sophie (22 April 2016). "Coignard – Derrière Macron, l'ombre de Jouyet". Le Point (in French). Archived from the original on 7 August 2017. Retrieved 6 August 2017.

- ^ "Ipesup, la prépa chérie des CSP+, est à vendre". Challenges (in French). Archived from the original on 9 January 2017. Retrieved 9 September 2017.

- ^ "Ipesup change de main pour grandir". Challenges (in French). Archived from the original on 20 July 2018. Retrieved 9 September 2017.

- ^ "Prépa ENA". Groupe Ipesup (in French). Archived from the original on 31 August 2017. Retrieved 9 September 2017.

- ^ "Laurence Parisot dément se tenir "prête" pour Matignon en cas de victoire d'Emmanuel Macron". Le Figaro (in French). 27 April 2017. ISSN 0182-5852. Archived from the original on 22 August 2017. Retrieved 7 August 2017.

- ^ Marnham, Patrick (4 February 2017). "Who's behind the mysterious rise of Emmanuel Macron?". The Spectator. Archived from the original on 6 May 2017. Retrieved 1 February 2017.

- ^ "Biography of Emmanuel Jean-Michel Frédéric Macron of France". Biography.com. A&E Television Networks. 17 May 2017. Archived from the original on 13 May 2017. Retrieved 17 May 2017.

- ^ "Emmanuel Macron s'explique sur ses anciens revenus de banquier". Le Point (in French). 19 February 2017. Archived from the original on 26 March 2017. Retrieved 1 February 2017.

- ^ "Décret n° 2010-223 du 4 mars 2010 relatif à la commission pour la libération de la croissance française". 4 March 2010. Archived from the original on 7 August 2017. Retrieved 7 August 2017.

- ^ "Au fait, il faisait quoi chez Rothschild, Emmanuel Macron ?". L'Obs (in French). Archived from the original on 27 July 2017. Retrieved 7 August 2017.

- ^ Chaperon, Isabelle (10 May 2017). "Les années Rothschild d'Emmanuel Macron". Le Monde (in French). ISSN 1950-6244. Archived from the original on 7 August 2017. Retrieved 7 August 2017.

- ^ Tricornot, Adrien de; Weisz, Johan (10 February 2017). "Comment Macron m'a séduit puis trahi" [How Macron seduced then betrayed me]. StreetPress (in French). Archived from the original on 2 June 2017. Retrieved 7 August 2017.

- ^ "Rothschild & Cie coopte trois nouveaux associés". Les Échos. France. 16 December 2010. Archived from the original on 8 October 2017. Retrieved 7 August 2017.

- ^ "Macron, ce chouchou des patrons qui succède à Montebourg". Challenges (in French). Archived from the original on 19 March 2017. Retrieved 7 August 2017.

- ^ Brigaudeau, Anne (5 May 2017). "Quand Emmanuel Macron était banquier d'affaires : "Un élément prometteur, mais sans plus"". France Info (in French). Archived from the original on 12 September 2023. Retrieved 15 August 2023.

- ^ "Macron, la première marche". Les Échos. France. 27 January 2017. Archived from the original on 7 August 2017. Retrieved 7 August 2017.

- ^ a b "La bombe Macron". L'Express (in French). 2 September 2014. Archived from the original on 2 August 2017. Retrieved 2 August 2017.

- ^ "Macron dit ce qu'il a fait de ses trois millions d'euros de revenus". Lejdd.fr. Archived from the original on 7 January 2019. Retrieved 6 January 2019.

- ^ "Emmanuel Macron's Rothschild years make him an easy election target". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 17 November 2019. Retrieved 10 December 2018.

- ^ Tyler Durden (25 April 2017). "Meet The Real Emmanuel Macron: Consummate Banker Puppet, Bizarre Elitist Creation". CECE – POLITICAL INSTITUTIONS. Archived from the original on 1 June 2021. Retrieved 28 May 2021.

- ^ a b "Macron, ce jeune chevènementiste". Marianne (in French). 12 November 2015. Archived from the original on 18 May 2017. Retrieved 2 August 2017.

- ^ Prissette, Nicholas (2016). Emmanuel Macron en marche vers l'Élysée. Plon. p. 79.

- ^ a b "Avec Macron, l'Elysée décroche le poupon". Libération (in French). Archived from the original on 19 July 2017. Retrieved 2 August 2017.

- ^ a b "Emmanuel Macron n'est plus encarté au Parti socialiste". Le Figaro (in French). 18 February 2015. ISSN 0182-5852. Archived from the original on 28 February 2017. Retrieved 2 August 2017.

- ^ "Emmanuel Macron: l'homme du Président". Visions Mag (in French). 24 February 2014. Archived from the original on 2 August 2017. Retrieved 2 August 2017.

- ^ Bourmaud, François-Xavier (2016). Emmanuel Macron: le banquier qui voulait être roi. l'Archipel. p. 224. ISBN 978-2-8098-1873-4.

- ^ "Arrêté du 15 mai 2012 portant nomination à la présidence de la République". Archived from the original on 2 August 2017. Retrieved 2 August 2017.

- ^ Prissette, Nicolas (2016). Emmanuel Macron en marche vers l'Élysée. Plon. p. 144.

- ^ "Pourquoi le gouvernement a cédé sur le salaire des patrons: les dessous d'un deal". L'Opinion (in French). 26 May 2013. Archived from the original on 2 August 2017. Retrieved 2 August 2017.

- ^ a b Berretta, Emmanuel (10 June 2014). "Hollande remanie l'Élysée et recrute Laurence Boone". Le Point (in French). Archived from the original on 14 June 2014. Retrieved 2 August 2017.

- ^ Visot, Marie (10 June 2014). "Laurence Boone, une forte tête à l'Élysée". Le Figaro (in French). ISSN 0182-5852. Archived from the original on 7 April 2019. Retrieved 2 August 2017.

- ^ a b "INFO OBS. Emmanuel Macron prépare son départ de l'Elysée". L'Obs (in French). Archived from the original on 2 August 2017. Retrieved 2 August 2017.

- ^ "Elysée: Hollande chamboule son cabinet". Les Échos. France. 10 June 2014. Archived from the original on 2 August 2017. Retrieved 2 August 2017.

- ^ "VIDEO. Le roman d'une ambition". Franceinfo (in French). 27 February 2015. Archived from the original on 2 July 2017. Retrieved 2 August 2017.

- ^ "Les redoutables réseaux de Macron". Challenges (in French). Archived from the original on 14 January 2017. Retrieved 2 August 2017.

- ^ Chabas, Charlotte (27 August 2014). "Emmanuel Macron, de " Mozart de l'Elysée " à ministre de l'économie". Le Monde (in French). ISSN 1950-6244. Archived from the original on 16 April 2017. Retrieved 2 August 2017.

- ^ Corbet, Sylvie; Ganley, Elaine (26 August 2014). "French gov't reshuffle expels dissident ministers". Associated Press. Archived from the original on 31 August 2014.

- ^ "Emmanuel Macron: son adversaire, c'est la défiance" (in French). Radio France Internationale. 29 August 2014. Archived from the original on 2 August 2017. Retrieved 2 August 2017.

- ^ V.V. (26 August 2014). "Macron, l'anti-Montebourg". Le Journal de Dimanche (in French). Archived from the original on 6 April 2017. Retrieved 2 August 2017.

- ^ a b Revault d'Allonnes, David (17 February 2015). "Loi Macron: comment le 49-3 a été dégainé comme un dernier recours". Le Monde.fr (in French). Archived from the original on 2 July 2017. Retrieved 16 April 2017.

- ^ Stothard, Michael (16 April 2015). "French companies fight back against Florange double-vote law". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 6 August 2017. Retrieved 5 August 2017.

- ^ "Renault: la bataille entre Ghosn et Macron prend fin". L'Obs (in French). Archived from the original on 18 July 2017. Retrieved 5 August 2017.

- ^ Magnaudeix, Mathieu. "Macron rattrapé par son bilan à Bercy". Mediapart (in French). Archived from the original on 6 August 2017. Retrieved 5 August 2017.

- ^ Laurent, Samuel (8 December 2014). "Ce que prévoit (ou pas) la future loi Macron". Le Monde (in French). ISSN 1950-6244. Archived from the original on 6 August 2017. Retrieved 5 August 2017.

- ^ Horobin, William; Meichtry, Stacy (9 March 2015). "5 Things About the Macron Law". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 21 July 2017. Retrieved 5 August 2017.

- ^ "Pourquoi le marteau du 49-3 est un outil indispensable". Les Échos. France. 24 February 2015. Archived from the original on 6 August 2017. Retrieved 5 August 2017.

- ^ "LOI n° 2015-990 du 6 août 2015 pour la croissance, l'activité et l'égalité des chances économiques Legifrance". legifrance.gouv.fr (in French). Archived from the original on 7 July 2017. Retrieved 5 August 2017.

- ^ Visot, Marie (18 September 2015). "La Loi Macron ne devrait créer que peu de croissance". Le Figaro (in French). ISSN 0182-5852. Archived from the original on 8 July 2017. Retrieved 5 August 2017.

- ^ Pouchard, Anne-Aël Durand et Alexandre (30 August 2016). "Quel est le bilan d'Emmanuel Macron au gouvernement ?". Le Monde (in French). ISSN 1950-6244. Archived from the original on 6 August 2017. Retrieved 5 August 2017.

- ^ "Des paroles et des actes. Invité : Emmanuel Macron". Franceinfo (in French). 5 March 2015. Archived from the original on 9 April 2023. Retrieved 26 July 2023.

- ^ Magnaudeix, Mathieu. "A l'Assemblée, le pouvoir installe ses têtes". Mediapart (in French). Archived from the original on 9 April 2023. Retrieved 26 July 2023.

- ^ "Lelab Europe1 – le meilleur de l'actualité politique sur le web". lelab.europe1.fr. Archived from the original on 7 January 2019. Retrieved 26 July 2023.

- ^ "Emmanuel Macron prend ses distances avec la déchéance de nationalité". Le Figaro. 9 February 2016. Archived from the original on 22 September 2023. Retrieved 26 July 2023.

- ^ "Macron, VRP de la French Tech en Israël". Les Échos. France. 8 September 2015. Archived from the original on 9 March 2019. Retrieved 26 July 2023.

- ^ Orange, Martine (12 June 2016). "Comment l'Europe a pesé sur la loi El Khomri". Mediapart (in French). Archived from the original on 10 June 2023. Retrieved 26 July 2023.

- ^ a b "Emmanuel Macron, le dernier maillon fort qui pourrait lâcher". L'Opinion (in French). 16 February 2016. Archived from the original on 8 March 2021. Retrieved 26 July 2023.

- ^ "Emmanuel Macron lance un " mouvement politique nouveau " baptisé " En marche ! "". Le Monde (in French). 6 April 2016. ISSN 1950-6244. Archived from the original on 6 August 2019. Retrieved 26 July 2023.

- ^ "Emmanuel Macron, un banquier social-libéral à Bercy". Le Parisien (in French). 26 August 2014. Archived from the original on 9 March 2019. Retrieved 26 July 2023.

- ^ "Macron veut voir son 'projet progressiste' défendu en 2017". Europe1. 27 June 2016. Archived from the original on 13 January 2017. Retrieved 26 July 2023.

- ^ Roger, Patrick (20 August 2016). "Macron précise son projet " progressiste " pour 2017". Le Monde (in French). Archived from the original on 5 August 2020. Retrieved 26 July 2023.

- ^ "La folle séquence médiatique d'Emmanuel Macron – Le Lab Europe 1" (in French). Archived from the original on 6 August 2017. Retrieved 26 July 2023.

- ^ "Finalement, le parti d'Emmanuel Macron est "et de droite, et de gauche" (mais surtout progressiste) – Le Lab Europe 1" (in French). Archived from the original on 24 April 2016. Retrieved 26 July 2023.

- ^ "France elections: Hollande slaps down ambitious minister Macron". BBC. 14 July 2016. Archived from the original on 8 April 2023. Retrieved 26 July 2023.

- ^ "Macron et l'héritage de Jeanne d'Arc". Le Journal du Dimanche (in French). 8 May 2016. Archived from the original on 2 August 2023. Retrieved 26 July 2023.

- ^ Gaël Brustier. "Macron ou la "révolution passive" des élites françaises". Slate (in French). Archived from the original on 23 June 2018. Retrieved 26 July 2023.

- ^ Visot, Marie (16 June 2016). "Michel Sapin-Emmanuel Macron : les meilleurs ennemis de Bercy". Le Figaro (in French). ISSN 0182-5852. Archived from the original on 9 July 2023. Retrieved 26 July 2023.

- ^ Prissette, Nicolas (2016). Emmanuel Macron en marche vers l'Élysée. Plon. p. 255.

- ^ "Ces journaux qui en pincent pour Macron". Libération (in French). Archived from the original on 11 September 2016. Retrieved 26 July 2023.

- ^ "La presse est unanime : Emmanuel Macron". Acrimed Action Critique Médias (in French). Archived from the original on 23 March 2023. Retrieved 26 July 2023.

- ^ "La macronite de l'Express". L'Humanité (in French). 27 October 2016. Archived from the original on 28 February 2017. Retrieved 26 July 2023.

- ^ "Le " cas Macron " : un feuilleton médiatique à suspense". Acrimed Action Critique Médias (in French). Archived from the original on 30 May 2023. Retrieved 26 July 2023.

- ^ "A Orléans, Emmanuel Macron a rendu hommage à Jeanne d'Arc qui " a su rassembler la France "". Le Monde (in French). 8 May 2016. ISSN 1950-6244. Archived from the original on 24 September 2023. Retrieved 26 July 2023.

- ^ "Avec Jeanne d'Arc, Macron attend des voix". Libération (in French). Archived from the original on 13 April 2023. Retrieved 26 July 2023.

- ^ "Macron à Orléans : c'est quoi les fêtes johanniques, si prisées des politiques?". LCI (in French). 26 July 2023. Archived from the original on 6 August 2017. Retrieved 6 August 2017.

- ^ "Macron: "L'honnêteté m'oblige à vous dire que je ne suis pas socialiste"". Libération (in French). Archived from the original on 12 April 2023. Retrieved 26 July 2023.

- ^ "Macron quits to clear way for French presidential bid". BBC News. 30 August 2016. Archived from the original on 17 July 2018. Retrieved 21 June 2018.

- ^ Julien Licourt; Yohan Blavignat (30 August 2016). "Macron évite soigneusement d'évoquer sa candidature". Le Figaro (in French). Archived from the original on 29 March 2017. Retrieved 30 August 2016.

- ^ "Emmanuel Macron démissionne pour se consacrer à son mouvement En Marche – France 24" (in French). France 24. 30 August 2016. Archived from the original on 6 August 2017. Retrieved 5 August 2017.

- ^ "Macron démissionne avec l'Elysée en ligne de mire". Les Échos (in French). France. 30 August 2016. Archived from the original on 30 August 2016. Retrieved 5 August 2017.

- ^ "Emmanuel Macron, la démission continue". Slate (in French). Archived from the original on 6 August 2017. Retrieved 5 August 2017.

- ^ "L'histoire secrète de la démission d'Emmanuel Macron". Franceinfo (in French). 31 August 2016. Archived from the original on 26 September 2017. Retrieved 5 August 2017.

- ^ "Emmanuel Macron: "J'ai démissionné pour être libre"". Archived from the original on 6 August 2017. Retrieved 5 August 2017.

- ^ d'Allonnes, David Revault (31 August 2016). "Hollande: " Emmanuel Macron m'a trahi avec méthode "". Le Monde (in French). ISSN 1950-6244. Archived from the original on 6 August 2017. Retrieved 5 August 2017.

- ^ "Ifop – Les Français et la démission d'Emmanuel Macron du gouvernement". ifop.com (in French). Archived from the original on 27 February 2017. Retrieved 5 August 2017.

- ^ Wieder, Thomas (7 April 2016). "Le pari libéral d'Emmanuel Macron". Le Monde (in French). ISSN 1950-6244. Archived from the original on 24 June 2019. Retrieved 5 August 2017.

- ^ Mourgue, Marion (18 May 2016). "Les levées de fonds au profit d'Emmanuel Macron se poursuivent". Le Figaro (in French). ISSN 0182-5852. Archived from the original on 9 December 2017. Retrieved 5 August 2017.

- ^ Combis, Hélène (19 June 2017). "'Président jupitérien': comment Macron compte régner sur l'Olympe". France Inter (in French). Archived from the original on 31 July 2020. Retrieved 24 April 2020.

- ^ "France's Macron Joins Presidential Race to 'Unblock France'". BBC, UK. 16 November 2016. Archived from the original on 23 April 2017. Retrieved 26 April 2017.

- ^ Boni, Marc de (16 March 2016). "2017 : Macron calme le jeu et se range derrière Hollande". Le Figaro (in French). ISSN 0182-5852. Archived from the original on 9 March 2019. Retrieved 26 July 2023.

- ^ "Macron a une drôle de définition des mots "traître" et "loyauté"". Le Huffington Post. 22 November 2016. Archived from the original on 19 April 2022. Retrieved 26 July 2023.

- ^ ""Révolution", le livre-programme de Macron se hisse dans le top des ventes". Challenges (in French). Archived from the original on 16 January 2017. Retrieved 26 July 2023.

- ^ "Macron refuse toute participation à la primaire, une "querelle de clan"" (in French). Archived from the original on 6 August 2017. Retrieved 6 August 2017.

- ^ "Primaire à gauche: Emmanuel Macron rejette les appels de Valls et Cambadélis" (in French). BFMTV. Archived from the original on 6 April 2017. Retrieved 6 August 2017.

- ^ "Cambadélis menace de sanction les soutiens de Macron". Le Point (in French). 2 September 2016. Archived from the original on 6 August 2017. Retrieved 6 August 2017.

- ^ "Qui sont les trente proches d'Emmanuel Macron qui comptent au sein d'En marche ! ?". Le Monde. Archived from the original on 18 January 2018. Retrieved 20 January 2018.

- ^ "Présidentielle: "On est vraiment entré dans la campagne", Macron montre les biceps à Paris". 20 Minutes (in French). 10 December 2016. Archived from the original on 6 August 2017. Retrieved 6 August 2017.

- ^ Vaudano, Maxime (22 December 2016). "Primaire de la droite: ce que les comptes racontent de la campagne". Le Monde (in French). ISSN 1950-6244. Archived from the original on 6 August 2017. Retrieved 6 August 2017.

- ^ Mathieu, Mathilde. "Macron et ses donateurs: et voilà le débat sur la transparence!". Mediapart (in French). Archived from the original on 6 August 2017. Retrieved 6 August 2017.

- ^ "Macron refuse de publier la liste de ses donateurs". Le Figaro (in French). Archived from the original on 6 August 2017. Retrieved 6 August 2017.

- ^ a b Roger, Patrick (26 January 2017). "Emmanuel Macron assure qu'" aucun centime " de Bercy n'a été utilisé pour En Marche !". Le Monde (in French). ISSN 1950-6244. Archived from the original on 6 August 2017. Retrieved 6 August 2017.

- ^ Vaudano, Maxime (3 February 2017). "Emmanuel Macron peut-il être inquiété dans l'affaire des " frais de bouche " ?". Le Monde (in French). ISSN 1950-6244. Archived from the original on 6 August 2017. Retrieved 6 August 2017.

- ^ "Emmanuel Macron et les 120.000 euros de Bercy". Le Journal du Dimanche (in French). 26 January 2017. Archived from the original on 3 August 2017. Retrieved 6 August 2017.

- ^ "Emmanuel Macron, bulle médiatique et fantasme d'une gauche en recomposition". Le Huffington Post. 12 March 2016. Archived from the original on 6 August 2017. Retrieved 6 August 2017.

- ^ Huertas, Hubert. "Croquis. De Mélenchon à Macron, les ressorts d'un déséquilibre". Mediapart (in French). Archived from the original on 6 August 2017. Retrieved 6 August 2017.

- ^ 미카엘라 비겔: 2017년 5월 9일, 프랑크푸르터 알제마이네 차이퉁, 9쪽.

- ^ "Pour Claude Perdriel, propriétaire de Challenges, "c'est Macron!"". L'Opinion (in French). 17 October 2016. Archived from the original on 6 August 2017. Retrieved 6 August 2017.

- ^ "Emmanuel Macron, "candidat des médias": autopsie d'un choix implicite". Libération (in French). Archived from the original on 6 August 2017. Retrieved 6 August 2017.

- ^ "Emmanuel Macron, le candidat des médias". Le Monde diplomatique (in French). 1 May 2017. Archived from the original on 6 August 2017. Retrieved 6 August 2017.

- ^ "Emmanuel Macron est-il le candidat des médias ?". Le Point (in French). 1 March 2017. Archived from the original on 6 August 2017. Retrieved 6 August 2017.

- ^ Sgherri, Marie-Sandrine (15 February 2017). "Emmanuel Macron, le produit de l'année ?". Le Point (in French). Archived from the original on 6 August 2017. Retrieved 6 August 2017.

- ^ "Comment Macron est devenu un phénomène médiatique". Challenges (in French). Archived from the original on 9 January 2017. Retrieved 6 August 2017.

- ^ "De DSK à Macron, l'étonnant parcours d'Ismaël Emelien". L'Express (in French). 25 October 2016. Archived from the original on 8 May 2017. Retrieved 6 August 2017.

- ^ "BFMTV diffuse autant de Macron que de Fillon, Hamon, Mélenchon et Le Pen réunis !". Marianne (in French). 21 February 2017. Archived from the original on 22 February 2017. Retrieved 6 August 2017.

- ^ "Bernard Mourad quitte Altice pour rejoindre l'équipe d'Emmanuel Macron". Challenges (in French). Archived from the original on 25 January 2024. Retrieved 6 August 2017.

- ^ "Présidentielle: polémique après une poignée de mains entre Emmanuel Macron et Ruth Elkrief". Franceinfo (in French). 27 April 2017. Archived from the original on 6 August 2017. Retrieved 6 August 2017.

- ^ "Bayrou propose "une offre d'alliance" à Macron qui "accepte"". Libération (in French). Archived from the original on 23 September 2017. Retrieved 6 August 2017.

- ^ "Emmanuel Macron et François Bayrou, l'alliance pour la présidentielle". L'Express (in French). 22 February 2017. Archived from the original on 25 January 2024. Retrieved 6 August 2017.

- ^ "Sondage: Fillon s'effondre et serait éliminé dès le 1er tour". Challenges (in French). Archived from the original on 13 August 2020. Retrieved 6 August 2017.

- ^ "Emmanuel Macron président selon un nouveau sondage". RTL.fr (in French). Archived from the original on 19 August 2017. Retrieved 6 August 2017.

- ^ Pauline De Saint-Rémy; Loïc Farge (16 February 2017). "Certains proches de Macron s'interrogent sur "l'absence de programme"". RTL. Archived from the original on 4 March 2017. Retrieved 3 March 2017.

- ^ David Ponchelet (2 March 2017). "Programme d'Emmanuel Macron: que promet-il pour les Outre-mer ?". franceinfo. Archived from the original on 2 March 2017. Retrieved 3 March 2017.

- ^ "Qui sont les soutiens d'Emmanuel Macron ?". Le Monde. 28 February 2017. Archived from the original on 2 March 2017. Retrieved 3 March 2017.

- ^ "La grande mosquée de Paris appelle à voter "massivement" Macron". Le Figaro (in French). 24 April 2017. Archived from the original on 28 April 2017. Retrieved 27 April 2017.

- ^ "Emmanuel Macron se voit en "président des patriotes face à la menace nationaliste"". Le Parisien. 23 April 2017. Archived from the original on 19 May 2017. Retrieved 6 August 2017.

- ^ Berdah, Arthur (24 April 2017). "François Hollande: "Pour ma part, je voterai Emmanuel Macron"". Le Figaro (in French). ISSN 0182-5852. Archived from the original on 6 August 2017. Retrieved 6 August 2017.

- ^ "융커는 2017년 4월 28일 웨이백 머신에 보관된 마크롱에 대한 지지로 전통을 깨뜨렸습니다." EU 관찰자 2017년 4월 24일

- ^ "오바마는 2017년 4월 21일 웨이백 머신(Wayback Machine)에서 주요 투표를 앞두고 프랑스 대선 후보 마크롱의 행운을 기원합니다." CNBC 2017년 4월 21일

- ^ "Débat Macron-Le Pen: la presse étrangère abasourdie par la violence des échanges". La Tribune (in French). Archived from the original on 6 August 2017. Retrieved 6 August 2017.

- ^ Mark Stone (5 March 2017). "Is Russia interfering in the French election? One of Emmanuel Macron's aides claims so". Sky News. Archived from the original on 16 May 2017. Retrieved 6 May 2017.

- ^ "En marche ! dénonce un piratage " massif et coordonné " de la campagne de Macron". Le Monde (in French). 6 May 2017. ISSN 1950-6244. Archived from the original on 18 August 2017. Retrieved 2 August 2017.

- ^ "Les 'Macron Leaks', itinéraire d'une opération de déstabilisation politique". rts.ch (in French). Archived from the original on 10 May 2017. Retrieved 2 August 2017.

- ^ Eric Auchard and Bate Felix (5 May 2017). "Macron's French presidential campaign emails leaked online". Reuters. Frankfurt/Paris. Archived from the original on 7 May 2017. Retrieved 6 May 2017.

- ^ a b "La campagne de Macron cible de tentatives de piratage de hackers russes". Le Point (in French). 25 April 2017. Archived from the original on 2 August 2017. Retrieved 2 August 2017.

- ^ "WikiLeaks releases thousands of hacked Macron campaign emails". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 10 January 2022. Retrieved 2 August 2017.

- ^ "French election: Macron takes action over offshore claims". BBC News. 4 May 2017. Archived from the original on 8 July 2017. Retrieved 2 August 2017.

- ^ "Résultats de l'élection présidentielle 2017". interieur.gouv.fr/Elections/Les-resultats/Presidentielles/elecresult__presidentielle-2017 (in French). Archived from the original on 10 July 2017. Retrieved 6 August 2017.

- ^ "Macron va démissionner de la présidence d'En marche!". Le Figaro (in French). Archived from the original on 6 August 2017. Retrieved 6 August 2017.

- ^ "Les 577 candidats de "La République en marche" seront connus jeudi 11 mai". La Tribune (in French). Archived from the original on 6 August 2017. Retrieved 6 August 2017.

- ^ Plowright, Adam (7 May 2017). "Emmanuel Macron: a 39-year-old political prodigy". MSN. Archived from the original on 25 September 2020. Retrieved 20 February 2020.

- ^ "En direct, Emmanuel Macron élu président: " Je défendrai la France, ses intérêts vitaux, son image "". Le Monde. 7 May 2017. Archived from the original on 7 May 2017. Retrieved 7 May 2017.

- ^ Leicester, John; Corbet, Sylvie. "Emmanuel Macron becomes France's youngest president". Toronto Sun. Associated Press. Archived from the original on 29 July 2017. Retrieved 14 May 2017.

- ^ "Macron the mould-breaker – France's youngest leader since Napoleon". Reuters. 7 May 2017. Archived from the original on 6 July 2017. Retrieved 2 July 2017.

- ^ C.Sa (8 May 2017). "Passation de pouvoir: François Hollande passera "le flambeau" à Macron dimanche 14 mai". Le Parisien (in French). Archived from the original on 8 May 2017. Retrieved 8 May 2017.

- ^ Grammont, Stéphane (14 May 2017). "Patrick Strzoda, ancien préfet de Bretagne, directeur de cabinet d'Emmanuel Macron". France 3 Bretagne. Archived from the original on 9 July 2023. Retrieved 15 May 2017.

- ^ Penicaud, Céline (14 May 2017). "Le parcours fulgurant d'Ismaël Emelien, le nouveau conseiller spécial d'Emmanuel Macron". BFM TV. Archived from the original on 16 May 2017. Retrieved 15 May 2017.

- ^ "France's Macron names Republican Philippe as PM". BBC News. 15 May 2017. Archived from the original on 15 May 2017. Retrieved 15 May 2017.

- ^ "Le premier ministre Philippe prépare " un gouvernement rassembleur de compétences "". Le Monde. 15 May 2017. Archived from the original on 15 May 2017. Retrieved 15 May 2017.

- ^ Narayan, Chandrika (15 May 2017). "French President Macron heads to Berlin for his first official foreign visit". CNN. Archived from the original on 16 May 2017. Retrieved 17 May 2017.

- ^ "Emmanuel Macron and Angela Merkel pledge to draw up 'common road map' for Europe". The Telegraph. 15 May 2017. Archived from the original on 10 January 2022. Retrieved 17 May 2017.

- ^ "Résultats des élections législatives 2017". interieur.gouv.fr/Elections/Les-resultats/Legislatives/elecresult__legislatives-2017. Archived from the original on 19 July 2017. Retrieved 26 August 2019.

- ^ "Macron's government admits French Senate elections a 'failure'". South China Morning Post. Associated Press. 25 September 2017. Archived from the original on 9 August 2022. Retrieved 8 August 2022.

- ^ "France's Macron picks Jean Castex as PM after Philippe resigns". BBC News. 3 July 2020. Archived from the original on 3 July 2020. Retrieved 17 May 2021.

- ^ Momtaz, Rym (3 July 2020). "Picking low-profile French PM, Macron bets big on himself". Politico. Archived from the original on 8 May 2021. Retrieved 17 May 2021.

- ^ "France bans hiring of spouses by politicians in wake of Fillon scandal". Reuters. 27 July 2017. Archived from the original on 9 August 2017. Retrieved 9 August 2017.

- ^ "French vote brings Macron's anti-sleaze law closer". Anadolu Agency. Archived from the original on 9 August 2017. Retrieved 9 August 2017.

- ^ Masters, James. "Emmanuel Macron under fire over wife's 'First Lady' role". CNN. Archived from the original on 8 August 2017. Retrieved 9 August 2017.

- ^ "France: Macron to abandon plans for official first lady". BBC News. 8 August 2017. Archived from the original on 8 August 2017. Retrieved 9 August 2017.

- ^ "France's parliament approves bill to clean up politics". Reuters. 9 August 2017. Archived from the original on 12 August 2017. Retrieved 12 August 2017.

- ^ a b Pierre Briacon, Emmanuel Macron은 노동 개혁에 정면으로 뛰어들었습니다. 프랑스의 새 대통령은 노동 운동과 패스트트랙 법안의 분열에 기대를 걸고 있습니다. 2017년 8월 2일 폴리티코 웨이백 머신(2017년 5월 17일)에 보관되어 있습니다.

- ^ a b 리즈 올더만, 프랑스 노동개혁에서 노조 지도자가 2017년 7월 31일 웨이백 머신, 뉴욕 타임즈(2017년 6월 20일)에 보관된 타협안을 제시하고 있습니다.

- ^ "France's Macron, on Eastern Europe trip, to raise issue of cheap labor". Reuters. 7 August 2017. Archived from the original on 29 December 2017. Retrieved 29 December 2017.

- ^ Rubin, Alissa J. (31 August 2017). "France Unveils Contentious Labor Overhaul in Big Test for Macron". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 21 October 2017. Retrieved 20 October 2017.

- ^ Jennifer Thompson & Madison Marriage, Macron의 개혁 의제는 2017년 8월 3일, Financial Times의 Wayback Machine에 보관된 저항에 직면해 있습니다.

- ^ 마크롱이 2017년 8월 3일 AP통신 웨이백 머신에 보관된 프랑스 노동시장 개혁 계획을 매각하려고 합니다(2017년 5월 23일).

- ^ "French parliament approves Macron's labour reforms – France 24". France 24. 3 August 2017. Archived from the original on 8 August 2017. Retrieved 9 August 2017.

- ^ "Macron signs French labor reform decrees". Reuters. Archived from the original on 21 October 2017. Retrieved 20 October 2017.

- ^ "France sees big drop in unemployment rate in boost for Macron". 25 October 2017. Archived from the original on 28 October 2017. Retrieved 27 October 2017.

- ^ Willsher, Kim (16 January 2018). "France will not allow another refugee camp in Calais, says Macron". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 12 February 2018. Retrieved 11 February 2018.

- ^ Chassany, Anne-Sylvaine (16 January 2018). "Macron tries to answer critics by striking a balance on migration". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 12 February 2018. Retrieved 11 February 2018.

- ^ "이탈리아는 '오만한' 프랑스가 이주의 주적이 될 수 있다고 말합니다." 2018년 6월 24일 웨이백 머신에 보관되었습니다. 로이터 통신.

- ^ "France to 'take back control' of immigration policy". Luxembourg Times. 6 November 2019. Archived from the original on 7 November 2019. Retrieved 6 November 2019.

- ^ Chrisafis, Angelique (19 July 2017). "Head of French military quits after row with Emmanuel Macron". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 21 July 2017. Retrieved 22 July 2017.

- ^ "French army chief resigns over Macron spat". Politico. 19 July 2017. Archived from the original on 19 July 2017. Retrieved 22 July 2017.

- ^ "Macron names François Lecointre new armed forces chief". France 24. 19 July 2017. Archived from the original on 22 July 2017. Retrieved 22 July 2017.

- ^ "French government sees EU credibility in reach with 2018 budget". Reuters. Archived from the original on 21 October 2017. Retrieved 20 October 2017.

- ^ "Macron fights 'president of the rich' tag after ending wealth tax". Reuters. Archived from the original on 21 October 2017. Retrieved 20 October 2017.

- ^ Dyson, Richard; Meadows, Sam (27 October 2017). "British expats among those benefiting as Macron slashes French wealth tax". The Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Archived from the original on 10 January 2022. Retrieved 27 October 2017.

- ^ Samuel, Henry (2 February 2018). "Emmanuel Macron takes France by surprise by unveiling 'voluntary redundancy' plan for bloated state sector". The Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Archived from the original on 10 January 2022. Retrieved 11 February 2018.

- ^ "France's Resistance to Change Grows as Macron Vows New Pension Plan". TrueNewsSource. Archived from the original on 9 December 2019. Retrieved 8 December 2019.

- ^ "Will Macron's Compromise on Pension Plan Mellow Protests in France?". True News Source. Archived from the original on 15 January 2020. Retrieved 14 January 2020.

- ^ Keohane, David (29 February 2020). "French government adopts pension reform by decree". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 19 April 2022. Retrieved 29 February 2020.

- ^ Elzas, Sarah (13 January 2021). "Macron to revive controversial pension overhaul once Covid is under control". RFI. Archived from the original on 25 August 2023. Retrieved 25 August 2023.

- ^ "Macron urges French police to make full use of draconian anti-terror powers". 19 October 2017. Archived from the original on 24 May 2018. Retrieved 23 May 2018.

- ^ "France to enshrine some state of emergency measures into law". Deutsche-Welle. Archived from the original on 21 October 2017. Retrieved 20 October 2017.

- ^ "French parliament passes controversial anti-terror law". Anadolu Agency. Archived from the original on 21 October 2017. Retrieved 20 October 2017.

- ^ "French parliament adopts controversial anti-terror bill". France 24. Archived from the original on 20 October 2017. Retrieved 20 October 2017.

- ^ "French parliament adopts controversial anti-terror bill". Deutsche-Welle. Archived from the original on 7 November 2017. Retrieved 5 November 2017.

- ^ "Macron rejects Corsican language demand". BBC News. 7 February 2018. Archived from the original on 10 February 2018. Retrieved 11 February 2018.

- ^ "Macron backs Corsica mention in French constitution, rejects other dem". Reuters U.K. Archived from the original on 12 February 2018. Retrieved 11 February 2018.

- ^ "Emmanuel Macron to propose reorganization of Islam in France". Politico. 11 February 2018. Archived from the original on 11 February 2018. Retrieved 11 February 2018.

- ^ "'Their knuckles turned white': Donald Trump and Emmanuel Macron's awkward handshake". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 10 January 2022. Retrieved 21 July 2017.

- ^ "Macron 'wins battle of the alphas' in handshake with Donald Trump". London Evening Standard. 25 May 2017. Archived from the original on 3 August 2017. Retrieved 21 July 2017.

- ^ "Macron slams Russian media 'lies' during muscular exchange with Putin at Versailles". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 10 January 2022. Retrieved 21 July 2017.

- ^ "Macron denounces Russian media on Putin visit". BBC News. Archived from the original on 9 July 2017. Retrieved 21 July 2017.

- ^ Chrisafis, Angelique (29 May 2017). "Macron warns over Syrian chemical weapons in frank meeting with Putin". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 21 July 2017. Retrieved 21 July 2017.

- ^ 테리사 메이와 에마뉘엘 마크롱의 시리아 공습에 대한 성명서는 2018년 4월 15일 뉴욕 타임즈의 웨이백 머신에 보관되었습니다(2018년 4월 13일).

- ^ 헬레네 쿠퍼, 토마스 기븐스-네프 & 벤 허바드, 미국, 영국, 프랑스가 화학무기 의심 공격으로 시리아를 공격했습니다. (2018년 4월 13일, 뉴욕 타임즈) 웨이백 머신에서 보관된 2018년 4월 14일.

- ^ "Emmanuel Macron: Fighting Islamist terror is France's top priority". Deutsche-Welle. Archived from the original on 21 October 2017. Retrieved 20 October 2017.

- ^ "France's Macron urges better long-term relations with Russia". BCNN1. 15 February 2020. Archived from the original on 20 May 2020. Retrieved 15 February 2020.

- ^ "The Macron method". Politico. 16 October 2019. Archived from the original on 19 November 2020. Retrieved 8 December 2020.

- ^ Oliphant, Roland; Chazan, David (25 August 2019). "Iranian foreign minister Javad Zarif arrives in Biarritz in surprise visit to G7 leaders summit". The Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Archived from the original on 10 January 2022. Retrieved 8 December 2020.

- ^ "France seals multi-billion dollar deals with China, but questions Belt and Road project". Reuters. 25 March 2019. Archived from the original on 29 May 2022. Retrieved 29 May 2022.

- ^ 림 맘타즈, "마크론이 중국 에어버스 주문으로 트럼프의 천둥을 훔치다: 프랑스가 베이징과 €30B 항공 계약 체결", 폴리티코 2019년 3월 25일 웨이백 머신에서 보관

- ^ "Macron seeks EU sanctions over Turkish 'violations' in Greek waters". Reuters. 23 July 2020. Archived from the original on 23 July 2020. Retrieved 14 August 2020.

- ^ "France's Macron slams Turkey's 'criminal' role in Libya". Al Jazeera. 30 June 2020. Archived from the original on 23 August 2020. Retrieved 14 August 2020.

- ^ "Turkey warns Egypt over Libya and lashes out at Macron's role". The Japan Times. 20 July 2020. Archived from the original on 4 February 2021. Retrieved 14 August 2020.

- ^ "France-Turkey spat over Libya arms exposes NATO's limits". Associated Press. 5 July 2020. Archived from the original on 3 March 2021. Retrieved 14 August 2020.

- ^ Riley-Smith, Ben (12 June 2021). "Boris Johnson infuriated after Emmanuel Macron suggested Northern Ireland was not part of UK". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 10 January 2022. Retrieved 24 June 2021.

- ^ "G7 summit: Northern Ireland part of one great indivisible UK, says PM". BBC News. 13 June 2021. Archived from the original on 24 June 2021. Retrieved 24 June 2021.

- ^ Woodcock, Andrew (15 June 2021). "Brexit row deepens as Elysee Palace rejects claims of Macron confusion over Northern Ireland". Independent. Archived from the original on 24 June 2021. Retrieved 24 June 2021.

- ^ "Explainer: Why is a submarine deal sparking a diplomatic crisis?". www.aljazeera.com. Archived from the original on 3 December 2021. Retrieved 25 September 2021.

- ^ Shields, Bevan (18 September 2021). "France recalls its ambassadors to Australia and United States amid submarine fury". The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 17 September 2021. Retrieved 18 September 2021.

- ^ Wadhams, Nick; Adghirni, Samy; Nussbaum, Ania (17 September 2021). "France Recalls Its Ambassador to U.S. for First Time Over Subs". Bloomberg L.P. Archived from the original on 21 September 2021. Retrieved 18 September 2021.

- ^ "Macron, Biden agree to soothe tensions after submarine row". France 24. 22 September 2021. Archived from the original on 23 September 2021. Retrieved 25 September 2021.

- ^ Fung, Katherine (21 September 2021). "Read Joe Biden and Emmanuel Macron's Rare Joint Statement on Recent Rift". newsweek.com. Archived from the original on 25 September 2021. Retrieved 25 September 2021.

- ^ "Trattato tra Italia e Francia: Draghi e Macron siglano l'intesa". rainews (in Italian). Archived from the original on 30 November 2021. Retrieved 30 November 2021.

- ^ 퀴리날레 조약: 프랑스와 이탈리아의 새로운 조약이 유럽의 힘의 균형을 바꿀 것인가요? 2022년 1월 25일 Wayback Machine, EuroNews에 보관

- ^ McGee, Luke (8 April 2022). "Emmanuel Macron has a grand vision for the West. Putin has exposed the limits of his influence". CNN. Archived from the original on 29 April 2022. Retrieved 29 April 2022.

- ^ Gijs, Camille (22 April 2022). "Macron: Keep talking to Putin to avoid 'new world war'". Politico Europe. Archived from the original on 26 April 2022. Retrieved 29 April 2022.

- ^ "Popularité: Macron fait un peu mieux que Hollande, un peu moins bien que Sarkozy, deux semaines après l'élection". LCI (in French). Archived from the original on 2 August 2017. Retrieved 2 August 2017.

- ^ "Cote de popularité: 62% des Français satisfaits d'Emmanuel Macron président (sondage)" (in French). Archived from the original on 2 August 2017. Retrieved 2 August 2017.

- ^ "French President Macron, PM Philippe approval ratings rise: poll". Reuters. 24 June 2017. Archived from the original on 2 August 2017. Retrieved 2 August 2017.

- ^ "Nouvelle forte baisse de la popularité d'Emmanuel Macron". Le Point (in French). 27 August 2017. Archived from the original on 31 October 2017. Retrieved 27 October 2017.

- ^ "French military chief quits after Macron clash". Sky News. Archived from the original on 2 August 2017. Retrieved 2 August 2017.

- ^ "Macron seizes French shipyards to block Italian take-over". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 10 January 2022. Retrieved 2 August 2017.

- ^ Chrisafis, Angelique (24 July 2017). "Housing benefit cuts spark row as Emmanuel Macron's poll ratings fall". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 2 August 2017. Retrieved 2 August 2017.

- ^ "Regain de popularité pour Emmanuel Macron et Édouard Philippe" (in French). Archived from the original on 30 September 2017. Retrieved 27 October 2017.

- ^ "L'action d'Emmanuel Macron". ELABE (in French). 27 September 2017. Archived from the original on 30 September 2017. Retrieved 27 October 2017.

- ^ "Réformes: 69% des Français jugent "injuste" la politique menée par Macron". L'Express (in French). 27 September 2017. Archived from the original on 31 October 2017. Retrieved 27 October 2017.

- ^ Sharkov, Damien (24 September 2018). "In France, Macron's Popularity Hits Record Low". Newsweek. Archived from the original on 3 December 2018. Retrieved 3 December 2018.

- ^ "Juillet 2020: la cote de confiance d'E. Macron atteint un niveau plus élevé qu'avant la crise". Elabe. 2 July 2020. Archived from the original on 24 February 2021. Retrieved 27 January 2021.

- ^ "Macron's popularity climbs after signing EU pandemic stimulus, reshuffling gov't". France24. 30 July 2020. Archived from the original on 26 January 2021. Retrieved 26 January 2021.

- ^ "Enquête, profil du suspect, réactions politiques... ce que l'on sait de l'affaire Benalla". Le Monde. 19 July 2018. Archived from the original on 19 July 2018. Retrieved 20 July 2018.

- ^ "Emmanuel Macron, premier président réélu depuis Jacques Chirac en 2002". L'Alsace (in French). 25 April 2022. Archived from the original on 18 August 2023. Retrieved 18 August 2023.

- ^ "Macron wins French presidential election". Le Monde. 24 April 2022. Archived from the original on 29 September 2023. Retrieved 24 April 2022.