주의력결핍 과잉행동장애

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder| 주의력결핍 과잉행동장애 | |

|---|---|

| |

| ADHD를 앓고 있는 사람들은 다른 사람들보다 일부 과제(예: 학교 공부)에 관심을 유지하기 위해 고군분투하지만, 즉시 보람을 느끼거나 흥미롭다고 생각되는 과제에 대해 비정상적으로 강렬한 수준의 관심을 유지할 수 있습니다. | |

| 전문 | |

| 증상 | |

| 통상발병 | 외상성 뇌 손상(TBI) 후 ADHD가 발생하지 않는 한 증상은 발달기에 발생해야 합니다. |

| 원인들 | 유전적(유전적, de novo) 및 덜한 정도의 환경적 요인(임신 중 생물학적 위험에 노출, 외상성 뇌손상) |

| 진단법 | 다른 가능한 원인이 배제된 후의 증상을 기준으로 합니다. |

| 감별진단 | |

| 치료 |

|

| 약 | |

| 빈도수. | 0.8–1.5% (2019, using DSM-IV-TR and ICD-10)[2] |

주의력결핍 과잉행동장애(ADHD)는 주의력결핍, 과잉행동, 충동성, 정서조절장애 등의 증상을 유발하는 집행기능장애를 특징으로 하는 신경발달장애로, 과도하고 만연하며, 다양한 맥락에서 장애를 일으키며, 그렇지 않으면 나이에 맞지 않습니다.[8]

ADHD 증상은 실행 기능 장애에서 발생하며,[17] 정서 조절 장애가 핵심 증상으로 간주되는 경우가 많습니다.[21] 시간 관리, 억제 및 지속적인 주의 집중과 같은 자기 조절의 어려움은 학업 성적 저하, 실업 및 수많은 건강 위험을 초래하여 [22]삶의[23] 질 저하와 13년의 직접적인 평균 수명 감소를 초래할 수 있습니다.[24][25] ADHD는 특히 현대 사회에서 추가적인 장애를 유발할 수 있는 일부 비정신 질환뿐만 아니라 다른 신경 발달 및 정신 질환과 관련이 있습니다.[26]

ADHD를 앓고 있는 사람들은 일시적으로 지연되는 결과가 있는 작업을 계속하기 위해 고군분투하지만 본질적으로 흥미롭거나 즉각적인 보상이 있다고 생각하는 작업에 대해 비정상적으로 오랫동안 주의를 기울일 수 있습니다.[27][16] 이것은 초집중(구어로 더 많이)[28] 또는 인내심 있는 응답으로 알려져 있습니다.[29] 이것은 사람이 분명히 다른 모든 것을 무시하거나 "조정"할 정도로 완전히 업무에 몰두하는 정신 상태이며, 종종 동의하지[27][30] 않으며 인터넷 중독[31] 및 가해 행동 유형과 같은 위험과 관련이 있을 수 있습니다.[32]

ADHD는 쌍둥이, 뇌 영상 및 분자 유전학 연구에 의해 뒷받침되는 실행 기능 및 자기 조절의 연속적인 차원 특성(벨 곡선)의 극단적인 하단을 나타냅니다.[33][12][34][16][35][36][37]

ADHD의 정확한 원인은 대부분 알려져 있지 않습니다.[38][39] ADHD를 앓고 있는 대부분의 사람들은 많은 유전적 및 환경적 위험 요소가 축적되어 장애를 유발합니다.[40] ADHD의 환경적 위험은 산전기에 가장 자주 영향을 미칩니다.[7] 그러나 드물게 단일 사건은 외상성 뇌 손상,[41][42][43] 임신 중 생물학적 위험 노출,[7] 주요 유전적 돌연변이[44] 또는 초기의 극심한 환경 결핍과 같은 ADHD를 유발할 수 있습니다.[45] 외상성 뇌손상 후 ADHD가 발생한 경우를 제외하고는 생물학적으로 뚜렷한 성인 발병 ADHD가 없습니다.[46][42][47]

징후 및 증상

주의력 과잉행동(성인의 불안), 파괴적 행동, 충동성은 ADHD에서 흔히 발생합니다.[48][49][50] 관계의 문제와 마찬가지로 학업적인 어려움도 빈번합니다.[49][50][51] 정상적인 수준의 부주의, 과잉행동, 충동성이 끝나고 개입이 필요한 상당한 수준이 시작되는 선을 긋기 어렵기 때문에 징후와 증상을 정의하기 어려울 수 있습니다.[52]

정신질환 진단 및 통계 매뉴얼(DSM-5) 제5판과 본문 개정(DSM-5-TR)에 따르면 같은 연령대의 다른 사람들보다 훨씬 더 많은 정도로 6개월 이상 증상이 있어야 합니다.[3][4] 이를 위해서는 17세 미만의 경우 주의력 결핍 또는 과잉 활동/충동 중 적어도 6가지 증상이 필요하고, 17세 이상의 경우 최소 5가지 증상이 필요합니다.[3][4] 증상은 적어도 두 가지 환경(예: 사회, 학교, 직장 또는 가정)에서 나타나야 하며, 기능의 질을 직접적으로 방해하거나 저하시켜야 합니다.[3] 또한 12세 이전에 여러 증상이 나타났음에 틀림없습니다.[4] 정신질환 진단 및 통계 매뉴얼(DSM-5) 제5판과 본문 개정(DSM-5-TR)에 따르면, 현재 필요한 증상 발현 연령은 12세입니다.[3][4][53]

프레젠테이션

ADHD는 크게 세 가지 프레젠테이션으로 나뉩니다.[4][52]

- 주로 부주의한 (ADHD-PI 또는 ADHD-I)

- 주로 과활성-임펄스(ADHD-PH 또는 ADHD-HI)

- 결합 프레젠테이션(ADHD-C).

표 "증상"은 두 가지 주요 분류 체계에서 ADHD-I 및 ADHD-HI의 증상을 나열합니다. 개인이 가지고 있는 다른 정신과 또는 의학적 상태로 더 잘 설명될 수 있는 증상은 그 사람에게 ADHD의 증상으로 간주되지 않습니다. DSM-5에서는 하위 유형이 폐기되고 시간에 따라 변화하는 장애의 표현으로 재분류되었습니다.

| 프레젠테이션 | DSM-5 그리고[3][4] 증상들 | ICD-11 증상[5] |

|---|---|---|

| 주의중 | 다른 정신과 또는 의학적 상태에 의해 이러한 증상이 더 잘 설명되는 상황을 제외한 어린이의 경우 다음 중 6개 이상, 성인의 경우 5개 이상

| 직업적, 학업적 또는 사회적 기능에 직접적으로 부정적인 영향을 미치는 부주의의 여러 증상. 보상이 잦은 고도의 자극적인 업무에 종사할 때는 증상이 나타나지 않을 수 있습니다. 증상은 일반적으로 다음과 같은 클러스터에서 발생합니다.

개인도 과잉행동-충동성의 기준을 충족할 수 있지만 부주의한 증상이 우세합니다. |

| 과활성-임펄스성 | 다른 정신과 또는 의학적 상태에 의해 이러한 증상이 더 잘 설명되는 상황을 제외한 어린이의 경우 다음 중 6개 이상, 성인의 경우 5개 이상

| 직업적, 학업적 또는 사회적 기능에 직접적으로 부정적인 영향을 미치는 과잉 행동/충동의 여러 증상. 일반적으로 이러한 현상은 구조가 있거나 자가 제어가 필요한 환경에서 가장 뚜렷하게 나타나는 경향이 있습니다. 증상은 일반적으로 다음과 같은 클러스터에서 발생합니다.

개인도 부주의의 기준을 충족할 수 있지만, 과활성-충동 증상이 우세합니다. |

| 합쳐진 | 부주의 및 과잉행동 충동 ADHD 모두의 기준을 충족합니다. | 부주의 및 과잉 행동 충동 ADHD 모두에 대한 기준이 충족되며, 둘 다 명확하게 우세하지 않습니다. |

ADHD를 앓고 있는 소녀와 여성은 과잉행동과 충동성 증상은 적지만 부주의와 주의 산만의 증상은 더 많이 보이는 경향이 있습니다.[54]

증상은 개인의 나이가 들수록 다르게, 미묘하게 표현됩니다.[55]: 6 과잉행동은 나이가 들수록 덜 명백해지는 경향이 있고 ADHD를 앓고 있는 청소년과 성인에서 내적 불안, 긴장을 풀거나 가만히 있는 것의 어려움, 수다스러움 또는 지속적인 정신 활동으로 바뀝니다.[55]: 6–7 성인기의 충동성은 생각 없는 행동, 조급함, 무책임한 지출 및 감각 추구 행동으로 나타날 수 있는 반면,[55]: 6 부주의는 쉽게 지루해지는 것, 조직에 대한 어려움, 과제에 남아 결정하는 것, 스트레스에 대한 민감성으로 나타날 수 있습니다.[55]: 6

이 상태에 대한 공식 증상으로 나열되지는 않았지만, 정서적 조절 장애나 기분 안정성은 일반적으로 ADHD의 일반적인 증상으로 이해됩니다.[18][55]: 6 모든 연령대의 ADHD가 있는 사람들은 사회적 상호작용과 우정 형성 및 유지와 같은 사회적 기술에 문제가 있을 가능성이 더 높습니다.[56] 이것은 모든 프레젠테이션에 해당됩니다. 비 ADHD 아동 청소년의 10~15%에 비해 ADHD 아동 청소년의 약 절반이 또래에 의한 사회적 거부반응을 경험합니다. 주의력 결핍이 있는 사람들은 사회적 상호 작용에 부정적인 영향을 미칠 수 있는 언어 및 비언어적 언어 처리에 어려움을 겪기 쉽습니다. 그들은 또한 대화 중에 표류하고, 사회적 신호를 놓치며, 사회적 기술을 배우는 데 어려움을 겪을 수 있습니다.[57]

화를 관리하는 데 어려움은 언어, 언어 및 운동 발달 지연과 마찬가지로 ADHD[58] 어린이에게 더 흔합니다.[59][60] 손글씨가 좋지 않은 것은 ADHD를 앓고 있는 어린이들에게 더 흔합니다.[61] 많은 상황에서 글씨를 잘 쓰지 못하는 것은 주의력 저하로 인해 그 자체로 ADHD의 증상이 될 수 있습니다. 이것이 널리 퍼진 문제인 경우 난독증[62][63] 또는 난독증에 기인할 수도 있습니다. ADHD, 난독증, 난독증의 증상이 상당히 중복되어 있으며,[64] 난독증 진단을 받은 10명 중 3명은 ADHD를 동시에 경험합니다.[65] 상당한 어려움을 겪지만 ADHD를 앓고 있는 많은 어린이들은 자신이 흥미롭다고 생각하는 과제와 과목에 대해 다른 어린이들과 같거나 더 큰 주의력을 가지고 있습니다.[66]

동반성

정신질환

어린이의 경우 ADHD가 다른 장애와 함께 발생하는 경우가 약 3분의 2 정도입니다.[66]

다른 신경 발달 조건은 일반적인 동반 질환입니다. ADHD 환자에서 21%의 비율로 동시에 발생하는 자폐 스펙트럼 장애(ASD)는 사회적 기술, 의사소통 능력, 행동 및 관심에 영향을 미칩니다.[67][68] ADHD와 ASD 모두 동일한 사람에게서 진단이 가능합니다.[4][page needed] 학습장애는 ADHD 아동의 약 20~30%에서 발생하는 것으로 밝혀졌습니다. 학습 장애에는 발달 언어 및 언어 장애, 학업 능력 장애가 포함될 수 있습니다.[69] 그러나 ADHD는 학습 장애로 간주되지 않지만 매우 자주 학업에 어려움을 초래합니다.[69] 지적장애와[4][page needed] 투렛증후군도[68] 흔합니다.

ADHD는 종종 방해, 충동 조절 및 행동 장애와 함께 발생합니다. 반대적 반항 장애(ODD)는 부주의한 표현을 가진 어린이의 약 25%와 결합된 표현을 가진 어린이의 50%에서 발생합니다.[4][page needed] 분노하거나 짜증나는 기분, 논쟁적이거나 반항적인 행동, 나이에 맞지 않는 복수심이 특징입니다. 행동장애(CD)는 ADHD 청소년의 약 25%에서 발생합니다.[4][page needed] 공격성, 재산 파괴, 속임수, 절도 및 규칙 위반이 특징입니다.[70] CD를 가지고 있는 ADHD 청소년은 성인기에 반사회적 성격장애가 발생할 가능성이 더 높습니다.[71] 뇌영상은 CD와 ADHD가 별개의 조건이라는 것을 뒷받침하는데, 전도장애는 측두엽과 변연계의 크기를 줄이고 안와전두엽 피질의 크기를 증가시키는 것으로 나타난 반면 ADHD는 소뇌와 전전두엽 피질의 연결을 더 광범위하게 감소시키는 것으로 나타났습니다. 행동장애는 ADHD보다 동기조절에 더 많은 장애를 수반합니다.[72] 간헐적 폭발 장애는 갑작스럽고 불균형한 분노의 폭발로 특징지어지며 ADHD를 가진 사람들에게서 일반 인구보다 더 자주 동시에 발생합니다.

불안과 기분 장애는 빈번한 동반 질환입니다. 불안장애는 기분장애(특히 조울증과 주요 우울증)와 마찬가지로 ADHD 인구에서 더 흔하게 발생하는 것으로 밝혀졌습니다. ADHD 아형 복합 진단을 받은 남학생은 기분장애가 있을 가능성이 높습니다.[73] ADHD를 앓고 있는 성인과 어린이도 조울증이 있는 경우가 있는데, 두 가지 상태를 정확하게 진단하고 치료하기 위해서는 세심한 평가가 필요합니다.[74][75]

수면장애와 ADHD는 공통적으로 공존합니다. ADHD 치료에 사용되는 약물의 부작용으로도 발생할 수 있습니다. ADHD 어린이의 경우 불면증이 가장 흔한 수면 장애이며 행동 치료가 선호됩니다.[76][77] 수면 시작과 관련된 문제는 ADHD를 앓고 있는 사람들 사이에서 흔히 발생하지만, 종종 그들은 깊은 잠을 자는 사람이고 아침에 일어나는 데 상당한 어려움을 겪습니다.[13] 멜라토닌은 수면 불면증이 있는 어린이들에게 가끔 사용됩니다.[78] 특히 수면장애 안절부절못 증후군은 ADHD 환자에서 더 많이 발생하는 것으로 밝혀졌으며 철분결핍성 빈혈이 원인인 경우가 많습니다.[79][80] 그러나 안절부절못하는 다리는 단순히 ADHD의 일부가 될 수 있으며 두 가지 장애를 구별하기 위해 신중한 평가가 필요합니다.[81] 지연 수면 단계 장애는 ADHD 환자의 일반적인 동반 질환이기도 합니다.[82]

약물 사용 장애와 같이 ADHD와 종종 동반되는 다른 정신 질환이 있습니다.[83] ADHD를 앓고 있는 사람은 약물 남용의 위험이 증가합니다.: 9 이것은 알코올이나 대마초에서 가장 흔하게 볼 수 있습니다.[55]: 9 그 이유는 ADHD 개인의 뇌에서 보상 경로의 변화, 자가 치료 및 심리 사회적 위험 요소의 증가 때문일 수 있습니다.: 9 이것은 ADHD의 평가와 치료를 더 어렵게 만드는데, 보통 심각한 물질 오용 문제는 더 큰 위험으로 인해 먼저 치료됩니다.[84] 다른 정신과적 질환으로는 사회적으로 적절하게 관계를 맺지 못하는 것을 특징으로 하는 [85]반응성 애착 장애와 ADHD 사례의 30~50%에서 동반 질환으로 발생하는 뚜렷한 주의력 장애인 인지 이탈 증후군, 발표와 상관없이 ADHD-PIP로 진단된 사례의 일부가 CDS를 가지고 있는 것으로 밝혀졌습니다.[86][87] ADHD가 있는 사람은 ADHD가 없는 사람에 비해 섭식장애가 발생하여 진단을 받을 확률이 3배나 높고, 반대로 섭식장애가 있는 사람은 섭식장애가 없는 사람에 비해 ADHD가 발생할 확률이 2배나 높습니다.[88]

트라우마

ADHD, 외상 및 부정적인 아동기 경험도 동반되며,[89][90] 이는 부분적으로 다른 진단 간의 표현 유사성에 의해 설명될 수 있습니다. ADHD와 PTSD의 증상은 상당한 행동 중복을 가질 수 있습니다. 특히 운동 불안정, 집중하기 어려움, 산만함, 짜증/분노, 정서적 위축 또는 조절 장애, 충동 조절 불량, 건망증이 둘 다 일반적입니다.[91][92] 이로 인해 외상 관련 장애나 ADHD가 다른 하나로 잘못 식별될 수 있습니다.[93] 게다가, 어린 시절의 충격적인 사건들은 ADHD의[94][95] 위험 요소입니다 - 그것은 구조적인 뇌의 변화와 ADHD 행동의 발달로 이어질 수 있습니다.[93] 마지막으로, ADHD 증상의 행동 결과는 개인이 외상을 경험할 가능성을 높입니다(따라서 ADHD는 외상 관련 장애의 구체적인 진단으로 이어집니다).[96][non-primary source needed]

비정신과적

일부 비정신성 질환은 ADHD의 동반 질환이기도 합니다. 여기에는 재발성 발작을 특징으로 하는 신경학적 상태인 뇌전증이 포함됩니다. ADHD와 비만, 천식과 수면장애,[99] 셀리악병과의 연관성은 잘 확립되어 있습니다.[100] ADHD 어린이는 편두통 위험은 [101]더 높지만 긴장형 두통 위험은 증가하지 않습니다. 또한 ADHD를 앓고 있는 어린이도 약물치료로 인해 두통을 경험할 수 있습니다.[102][103]

2021년 리뷰에 따르면 대사의 선천적 오류로 인한 여러 신경 대사 장애는 ADHD 병태 생리학 및 치료의 중심으로 간주되는 생물학적 메커니즘을 방해하는 공통 신경화학적 메커니즘에 수렴한다고 보고했습니다. 이는 임상적으로 가려지지 않도록 의료 서비스 간의 긴밀한 협업의 중요성을 강조합니다.[104]

2021년 6월, Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews는 ADHD 환자의 사고 발생 빈도 증가를 확인하거나 암시하는 82개 연구에 대한 체계적인 리뷰를 발표했으며, 그의 데이터는 수명 동안 ADHD 환자의 사고 또는 부상 유형과 전반적인 위험이 변화한다는 것을 시사했습니다.[105] 2014년 1월, 사고 분석 및 예방(Accident Analysis & Prevention)은 ADHD 운전자를 대상으로 교통 충돌의 상대적 위험을 조사한 16개 연구에 대한 메타 분석을 발표했는데, 노출에 대한 통제 없이 전체 상대적 위험 추정치 1.36, 출판 편향에 대한 통제 시 상대적 위험 추정치 1.29, 상대적 위험 추정치 1.29를 발견했습니다.노출에 대한 통제 시 23, 반대적 도전 장애 및/또는 행동 장애 동반 질환을 가진 ADHD 운전자에 대한 상대적 위험 추정치 1.[106][107]86.

문제가 있는 디지털 미디어 사용

2018년 4월, 국제 환경 연구 및 공중 보건 저널(International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health)은 인터넷 게임 장애(IGD)와 다양한 정신 병리학 사이의 연관성을 연구하는 24개의 연구에 대한 체계적인 검토를 발표했습니다. IGD와 ADHD 사이의 85%의 상관 관계를 발견했습니다.[108] 2018년 10월, PNAS USA는 아동 및 청소년의 스크린 미디어 사용과 ADHD 관련 행동 간의 관계에 대한 40년간의 연구를 체계적으로 검토한 결과, 아동의 미디어 사용과 ADHD 관련 행동 간에 통계적으로 작은 관계가 존재한다는 결론을 내렸습니다.[109] 2018년 11월 사이버심리학(Cyberpsychology)은 문제가 있는 스마트폰 사용과 충동성 특성 사이의 관계에 대한 증거를 발견한 5개 연구에 대한 체계적인 검토 및 메타 분석을 발표했습니다.[110] 2020년 10월, Journal of Behavior Addictions는 휴대전화 중독과 충동성 사이에 약-중등도의 긍정적인 연관성을 발견한 33,650명의 고등학생 피험자를 대상으로 한 40개의 연구에 대한 체계적인 검토와 메타 분석을 발표했습니다.[111] 2021년 1월, Journal of Psychiric Research는 ADHD 증상이 게임 장애와 일관되게 연관되어 있다는 것을 발견한 56,650명의 피험자를 포함한 29개 연구에 대한 체계적인 검토를 발표했습니다. ADHD 증상은 다른 ADHD 척도보다 부주의와 게임 장애 사이의 연관성이 더 높다는 것을 발견했습니다.[112]

2021년 7월, 정신 의학 분야의 프론티어들은 40개의 복셀 기반 형태 측정 연구와 59개의 기능적 자기 공명 영상 연구를 대조군과 비교한 메타 분석을 발표했는데, IGD와 ADHD 피험자는 부전두엽 피질(OFC)에서 장애를 구별하는 구조적 신경 영상 변화가 있다는 것을 발견했습니다. 그리고 IGD 피험자에 대한 전핵 및 보상 회로(OFC, 전방 싱귤레이트 피질 및 선조체 포함)에서 IGD 및 ADHD 피험자 모두에 대한 기능적 변화.[113] 2022년 3월, JAMA Psychiatry는 12세 이하 159,425명의 피험자를 대상으로 87건의 연구를 체계적으로 검토하고 메타 분석한 결과, 아동의 스크린 시간과 ADHD 증상 사이에 작지만 통계적으로 유의한 상관관계가 있음을 발견했습니다.[114] 2022년 4월, 발달신경심리학(Developmental Neuropsychology)은 11개 연구에 대한 체계적인 리뷰를 발표했는데, 한 연구를 제외한 모든 연구의 데이터는 어린이의 스크린 시간 증가가 주의력 문제와 관련이 있다고 제안했습니다.[115] 2022년 7월, Journal of Behavior Addictions는 6세에서 18세 사이의 2,488명의 피험자로 구성된 14개의 연구에 대한 메타 분석을 발표했습니다. ADHD 진단을 받은 피험자들이 대조군에 비해 훨씬 더 심각한 문제가 있는 인터넷 사용을 발견했습니다.[116]

2022년 12월, 유럽 아동 청소년 정신 의학은 2011년부터 2021년까지 발표된 28개 종단 연구에 대한 체계적 문헌 고찰을 발표하여 아동 및 청소년의 디지털 미디어 사용과 이후 ADHD 증상 간의 연관성을 발견했습니다(즉, 디지털 미디어 사용과 ADHD 증상 간의 상호 연관성). ADHD 증상이 있는 피험자들은 문제가 있는 디지털 미디어 사용에 더 많이 걸릴 가능성이 있었고, 디지털 미디어 사용 증가는 ADHD 증상의 이후 심각도 증가와 관련이 있었습니다.[117] 2023년 5월, Reviews on Environmental Health는 어린이 대상 81,234명을 대상으로 한 9개의 연구에 대한 메타분석을 발표했는데, 이 연구에서 어린이의 스크린 시간과 ADHD 위험 사이에 긍정적인 상관관계가 발견되었으며, 어린이의 스크린 시간이 많을수록 ADHD 발병에 크게 기여할 수 있다고 밝혔습니다.[118] 2023년 12월, Journal of Psychiric Research는 평균 연령 18.4세의 18,859명의 피험자를 대상으로 ADHD와 문제가 있는 인터넷 사용 사이에 유의미한 연관성을 발견한 24개의 연구에 대한 메타 분석을 발표했습니다.[119] Clinical Psychology Review는 ADHD와 게임 장애 사이의 연관성을 조사한 48개의 연구에 대한 체계적인 검토와 메타 분석을 발표했는데, 이 연구는 ADHD와 게임 장애 사이에 통계적으로 유의미한 연관성을 발견했습니다.[120]자살위험

2017년과 2020년에 실시된 체계적인 검토에 따르면 ADHD가 모든 연령대에서 자살 위험 증가와 관련이 있다는 강력한 증거가 발견되었으며, 아동기나 청소년기의 ADHD 진단이 중요한 미래 자살 위험 요소를 나타낸다는 증거도 증가하고 있습니다.[121][122] 잠재적인 원인으로는 ADHD와 기능 장애의 연관성, 부정적인 사회적, 교육적, 직업적 결과, 재정적 고통 등이 있습니다.[123][124] 2019년 메타 분석에 따르면 ADHD와 자살 스펙트럼 행동(자살 시도, 아이디어, 계획 및 완료된 자살) 사이에 유의한 연관성이 있는 것으로 나타났습니다. 조사된 연구 전체에서 ADHD가 있는 사람의 자살 시도 유병률은 18.9%인 반면 ADHD가 없는 사람의 경우 9.3%였습니다. 그리고 연구 결과는 다른 변수를 조정한 연구들 사이에서 상당히 복제되었습니다. 그러나 ADHD와 자살 스펙트럼 행동 사이의 관계는 개별 연구 전반에 걸쳐 혼합된 결과와 동반 정신 질환의 복잡한 영향으로 인해 불분명합니다.[123] ADHD와 자살 사이에 직접적인 관계가 있는지, ADHD가 동반질환을 통해 자살위험을 높이는지에 대한 명확한 자료가 없습니다.[122]

IQ 테스트 성능

특정 연구에 따르면 ADHD를 앓고 있는 사람들은 지능지수(IQ) 테스트에서 낮은 점수를 받는 경향이 있습니다.[125] ADHD를 앓고 있는 사람들 간의 차이와 주의 산만함과 같은 증상이 지적 능력보다는 낮은 점수에 미치는 영향력을 판단하기 어려워 그 중요성이 논란이 되고 있습니다. ADHD에 대한 연구에서는 표준화된 지능 측정에서 ADHD 점수가 평균 9점 낮음에도 불구하고 IQ가 낮은 사람을 제외한 많은 연구에서 IQ가 더 높을 수 있습니다.[126] 그러나 다른 연구에서는 지능이 높은 개인의 경우 ADHD 진단을 놓칠 위험이 증가하며, 이는 해당 개인의 보상 전략 때문일 수 있다고 반박합니다.[127]

성인을 대상으로 한 연구에 따르면 지능의 부정적인 차이는 의미가 없으며 관련 건강 문제로 설명될 수 있습니다.[128]

원인들

ADHD는 특히 유전적 요인(이러한 네트워크를 구축하고 조절하기 위한 다양한 유전자 변이 및 돌연변이) 또는 이러한 네트워크 및 영역의 개발에 대한 후천적 장애로 인해 발생할 수 있는 전전두엽 실행 네트워크에서 뇌의 오작동으로 인해 발생합니다. 실행 기능 및 자가 조절에 관여합니다.[129][16] 이들의 감소된 크기, 기능적 연결성 및 활성화는 ADHD의 병태생리뿐만 아니라 이러한 뇌 영역을 매개하는 노르아드레날린성 및 도파민성 시스템의 불균형에 기여합니다.[129][130]

유전적 요인이 중요한 역할을 합니다. ADHD는 유전율이 70-80%입니다. 나머지 20-30%의 분산은 뇌 손상을 제공하거나 생성하는 디노보 돌연변이 및 비공유 환경 요인에 의해 매개되며, 양육 가족 및 사회 환경의 중요한 기여는 없습니다.[137] 매우 드물게, ADHD는 염색체의 이상의 결과일 수도 있습니다.[138]

유전학

1999년 11월, 생물학적 정신 의학은 정신과 의사 조셉 비더만과 토마스 스펜서의 ADHD의 병태생리에 대한 문헌 고찰을 발표했는데, 쌍둥이 연구에서 ADHD의 평균 유전성 추정치는 0.8인 반면,[139] 그 이후의 가족인 쌍둥이, 심리학자 Stephen Faraone과 Henrik Larsson이 2019년 4월 Molecular Psychology에 발표한 입양 연구 문헌 리뷰에 따르면 평균 유전성 추정치는 0.74입니다.[140] 또한 진화 정신과 의사 랜돌프 M. 네세는 ADHD 역학에서 남녀 성비가 5:1이라는 것은 ADHD가 남성이 꼬리에 과도하게 표현되는 연속체의 끝일 수 있다는 것을 암시한다고 주장하면서 임상 심리학자 사이먼 배런-코헨이 자폐증 역학에서 성비를 유사체로 제시한 것을 예로 들었습니다.[141][142][143]

자연 선택은 적어도 45,000년 동안 ADHD에 대한 유전적 변이에 대항하여 작용해 왔으며, 이는 고대에는 ADHD가 적응 특성이 아니었음을 나타냅니다.[144] 유전자 돌연변이와 세대 간 제거율(자연 선택)의 균형에 의해 장애는 안정적인 속도로 유지될 수 있습니다. 수천 년에 걸쳐 이러한 유전자 변이는 더 안정적이 되어 장애 유병률이 감소합니다.[145] 인간 진화 전반에 걸쳐 ADHD와 관련된 EF는 시간에 걸쳐 우연성을 결합하여 인간의 미래 사회적 결과를 극대화하기 위해 즉각적인 사건에 대한 행동을 미래로 유도할 수 있는 능력을 제공할 가능성이 높습니다.[146]

ADHD는 74%의 높은 유전성을 가지고 있는데, 이는 인구 내 ADHD 존재의 74%가 유전적 요인에 기인한다는 것을 의미합니다. ADHD를 앓을 가능성을 약간 높이는 유전자 변형이 여러 개 있습니다. 다유전자적이며 각각 작은 영향을 미치는 많은 유전자 변형의 조합을 통해 발생합니다.[147][7] ADHD 어린이의 형제자매는 ADHD가 없는 어린이의 형제자매보다 장애가 발생할 가능성이 3~4배 높습니다.[148]

대규모 인구 연구에서 관찰된 모성 흡연의 연관성은 ADHD의 가족력을 조정한 후 사라지는데, 이는 임신 중 모성 흡연과 ADHD의 연관성이 흡연과 ADHD의 융합 위험을 높이는 가족적 또는 유전적 요인에 기인함을 나타냅니다.[149][150]

ADHD는 감소된 크기, 기능적 연결성 및 활성화뿐만[129] 아니라 임원 기능 및 자가 조절에 중요한 뇌 영역 및 네트워크에서 낮은 노르아드레날린성 및 도파민성 기능을[151][152] 나타냅니다.[129][37][16] 일반적으로 많은 유전자가 관련되어 있으며, 그 중 많은 유전자가 뇌 기능과 신경 전달에 직접적인 영향을 미칩니다.[129] 도파민과 관련된 사람들은 DAT, DRD4, DRD5, TAAR1, MAOA, COMT 및 DBH를 포함합니다.[153][154][155] ADHD와 관련된 다른 유전자로는 SERT, HTR1B, SNAP25, GRIN2A, ADRA2A, TPH2, BDNF 등이 있습니다.[156] 라트로필린 3이라는 유전자의 일반적인 변이는 약 9%의 사례를 담당하는 것으로 추정되며, 이 변이가 존재하면 사람들은 특히 자극제 약물에 반응합니다.[157] 도파민 수용체 D4 (DRD4–7R)의 7회 반복 변이는 도파민에 의해 유도된 증가된 억제 효과를 유발하며 ADHD와 관련이 있습니다. DRD4 수용체는 아데닐릴 사이클라제를 억제하는 G 단백질 결합 수용체입니다. DRD4-7R 돌연변이는 분할 주의를 반영하는 ADHD 증상을 포함한 광범위한 행동 표현형을 초래합니다.[158] DRD4 유전자는 새로움 추구 및 ADHD와 모두 관련이 있습니다. 유전자 GFOD1과 CDH13은 ADHD와 강한 유전적 연관성을 보입니다. CHD13은 ASD, 조현병, 조울증, 우울증과 연관되어 있어 흥미로운 후보 원인 유전자입니다.[135] 확인된 또 다른 후보 원인 유전자는 ADGRL3입니다. 제브라피쉬에서 이 유전자의 녹아웃은 복부 간뇌에서 도파민 기능의 손실을 일으키고 물고기는 과활성/충동 표현형을 나타냅니다.[135]

유전자 변이가 진단의 도구로 사용되기 위해서는 더 많은 검증 연구가 수행될 필요가 있습니다. 그러나 소규모 연구에 따르면 카테콜아민성 신경 전달 또는 시냅스의 SNARE 복합체와 관련된 유전자의 유전적 다형성은 자극제 약물에 대한 사람의 반응을 안정적으로 예측할 수 있습니다.[135] 희귀 유전자 변이는 침투율(장애 발생 가능성)이 훨씬 높은 경향이 있기 때문에 더 관련성이 높은 임상적 중요성을 보여줍니다.[159] 그러나 ADHD를 예측하는 단일 유전자가 없기 때문에 진단 도구로서의 유용성은 제한적입니다. ASD는 유전적 변이의 공통 및 드문 수준 모두에서 ADHD와 유전적 중복을 보여줍니다.[159]

환경

유전적 요인 외에도 일부 환경적 요인이 ADHD를 유발하는 역할을 할 수 있습니다.[160][161] 임신 중 알코올 섭취는 ADHD 또는 이와 같은 증상을 포함할 수 있는 태아 알코올 스펙트럼 장애를 유발할 수 있습니다.[162] 납 또는 폴리염화 비페닐과 같은 특정 독성 물질에 노출된 어린이는 ADHD와 유사한 문제가 발생할 수 있습니다.[38][163] 유기인산염 살충제인 클로르피리포스와 디알킬 인산염에 노출되면 위험이 증가하지만, 증거는 결정적이지 않습니다.[164] 임신 중 담배 연기에 노출되면 중추신경계 발달에 문제를 일으킬 수 있고 ADHD 위험을 높일 수 있습니다.[38][165] 임신 중 니코틴 노출은 환경적 위험이 될 수 있습니다.[166]

극도의 조산, 매우 낮은 출생 체중, 그리고 극도의 방임, 학대 또는 사회적 박탈은 또한 임신 중, 출생 시, 그리고 유아기에 특정 감염과 마찬가지로 위험을[167][38][168] 증가시킵니다. 이러한 감염에는 다양한 바이러스(홍역, 수두 대상포진 뇌염, 풍진, 엔테로바이러스 71)가 포함됩니다.[169] 외상성 뇌손상을 입은 어린이의 최소 30%는 나중에 ADHD가[170] 발생하고 약 5%의 경우 뇌손상으로 인한 것입니다.[171]

일부 연구에 따르면 소수의 어린이의 경우 인공 식품 염료 또는 방부제가 ADHD 또는 ADHD 유사 증상의 유병률 증가와 관련이 있을 수 [38][172]있지만 증거는 약하고 식품 민감성이 있는 어린이에게만 적용될 수 있습니다.[160][172][173] 유럽 연합은 이러한 우려를 바탕으로 규제 조치를 취했습니다.[174] 소수의 아이들은 특정 음식에 대한 과민증이나 알레르기가 ADHD 증상을 악화시킬 수 있습니다.[175]

저칼륨 감각 과잉 자극을 가진 사람은 주의력결핍 과잉행동장애(ADHD)로 진단되는 경우가 있어 ADHD의 하위 유형이 기계적으로 이해되고 새로운 방식으로 치료될 수 있는 원인을 가지고 있을 가능성이 제기됩니다. 감각 과부하는 경구 글루콘산칼륨으로 치료할 수 있습니다.

연구는 ADHD가 정제 설탕을 너무 많이 섭취하거나 텔레비전을 너무 많이 시청하거나, 양육 상태가 좋지 않거나, 가난하거나, 가족의 혼란으로 인해 발생한다는 일반적인 믿음을 지지하지 않습니다. 하지만, ADHD는 특정한 사람들에게 ADHD 증상을 악화시킬 수 있습니다.[48]

한 학급에서 가장 어린 아이들은 ADHD 진단을 받을 가능성이 더 높은 것으로 밝혀졌는데, 이는 아마도 그들이 나이가 많은 학급 친구들보다 발달적으로 뒤처져 있기 때문일 수 있습니다.[176][177] 한 연구는 5학년과 8학년의 가장 어린 아이들이 나이가 많은 또래들보다 자극제 약물을 사용할 가능성이 거의 두 배나 높다는 것을 보여주었습니다.[178]

어떤 경우에는, ADHD의 부적절한 진단은 개인에게 ADHD의 진정한 존재가 아닌, 기능하지 않는 가족이나 빈약한 교육 시스템을 반영할 수도 있습니다.[179][better source needed] 일부 국가의 부모들이 자녀에 대한 추가적인 재정적, 교육적 지원을 받을 수 있는 방법이라는 진단과 함께, 다른 경우에는 학업 기대를 높이는 것으로 설명될 수 있습니다.[171] ADHD의 전형적인 행동은 폭력과 정서적 학대를 경험한 아이들에게서 더 흔하게 발생합니다.[180]

병태생리학

ADHD의 현재 모델은 ADHD가 뇌의 신경전달물질 시스템 중 일부, 특히 도파민과 노르에피네프린을 포함하는 시스템의 기능 장애와 관련이 있음을 시사합니다.[181] 복부 분절 부위와 코에룰루스 유전자좌에서 시작되는 도파민과 노르에피네프린 경로는 뇌의 다양한 부위에 투사되어 다양한 인지 과정을 관장합니다.[182][14] 전전두엽 피질과 선조체에 투사되는 도파민 경로와 노르에피네프린 경로는 실행 기능(행동의 인지적 조절), 동기, 보상 인식 및 운동 기능을 조절하는 데 직접적인 책임이 있습니다.[181][14] 이러한 경로는 ADHD의 병리 생리학에서 중심적인 역할을 하는 것으로 알려져 있습니다.[182][14][183][184] 추가 경로가 있는 ADHD의 더 큰 모델이 제안되었습니다.[183][184]

뇌구조

ADHD를 앓고 있는 어린이의 경우 특정 뇌 구조에서 일반적으로 볼륨이 감소하며, 왼쪽 전전두엽 피질에서 볼륨이 비례적으로 더 많이 감소합니다.[181][185] 후두정 피질은 대조군에 비해 ADHD를 가진 사람들의 두께가 얇아지는 것을 보여줍니다. 전전두엽-전두엽-소뇌 및 전전두엽-후두엽 회로의 다른 뇌 구조도 ADHD가 있는 사람과 없는 사람 사이에 다른 것으로 밝혀졌습니다.[181][183][184]

부종, 편도체, 꼬리, 해마 및 푸타멘의 피질하 부피는 대조군에 비해 ADHD 환자에서 더 작게 나타납니다.[186] 구조 MRI 연구에서도 백색 물질의 차이가 밝혀졌는데, ADHD와 일반적으로 발달하는 청소년 사이의 반구 간 비대칭이 현저한 차이를 보였습니다.[187]

기능 MRI(fMRI) 연구를 통해 ADHD와 대조군 뇌 사이에 많은 차이가 있음이 밝혀졌습니다. 구조적 발견으로부터 알려진 것을 반영하여, fMRI 연구는 꼬리와 전전두피질 사이와 같은 피질하 영역과 피질하 영역 사이의 더 높은 연결성에 대한 증거를 보여주었습니다. 이러한 영역 간의 초연결성 정도는 부주의 또는 과잉 활동의 심각성과 상관관계가 있습니다. 반구면 측면화 과정도 ADHD와 관련이 있는 것으로 가정되었지만 경험적 결과는 주제에 대한 대조적인 증거를 보여주었습니다.[189][190]

신경전달물질 경로

이전에 ADHD 환자의 도파민 수송체 수가 증가한 것은 병태생리학의 일부라고 제안되었지만, 그 수가 증가한 것은 자극제 약물에 노출된 후의 적응 때문일 수도 있는 것으로 보입니다.[191] 현재 모델은 중피질 림프 도파민 경로와 유전자좌 코룰레우스-노라드레네르기 시스템을 포함합니다.[182][181][14] ADHD 정신자극제는 이러한 시스템에서 신경전달물질 활동을 증가시키기 때문에 치료 효능을 가지고 있습니다.[181][14][192] 세로토닌성, 글루타메이트성 또는 콜린성 경로에 추가로 이상이 있을 수 있습니다.[192][193][194]

임원 기능 및 동기 부여

ADHD의 증상은 특정 실행 기능(예: 주의력 제어, 억제 제어 및 작업 기억)의 결핍에서 발생합니다.[181] 실행 기능은 선택한 목표 달성을 촉진하는 행동을 성공적으로 선택하고 모니터링하는 데 필요한 일련의 인지 프로세스입니다.[14][15] ADHD 개인에게 발생하는 실행 기능 장애는 조직적 유지, 시간 지키기, 과도한 미루기, 집중력 유지, 주의 집중, 주의 산만 무시, 감정 조절, 세부 사항 기억 등의 문제를 초래합니다.[13][181][14] ADHD를 앓고 있는 사람들은 장기 기억력이 손상되지 않은 것으로 보이며, 장기 기억력의 결함은 작업 기억력의 손상에 기인하는 것으로 보입니다.[195] 사람이 나이가 들면서 뇌의 성숙 속도와 행정 통제에 대한 증가하는 요구로 인해 ADHD 장애는 청소년기 또는 심지어 성인 초기까지 완전히 나타나지 않을 수 있습니다.[13] 반대로, 잠재적으로 ADHD에서 다양한 종적 경향을 보이는 뇌 성숙 궤적은 성인이 된 후 나중에 임원 기능의 개선을 지원할 수 있습니다.[189]

ADHD는 또한 어린이의 동기 부여 결핍과 관련이 있습니다. ADHD를 앓고 있는 아이들은 종종 단기적인 보상보다 장기적인 보상에 집중하기 어렵고, 단기적인 보상을 위해 충동적인 행동을 보입니다.[196]

신경활성물질에 대한 역설적 반응

이 그룹의 중추신경계에서 구조적으로 변경된 신호 처리의 또 다른 징후는 눈에 띄게 흔한 역설적 반응(Paradoxical reaction,c. 환자의 10-20%)입니다. 이것들은 정상적인 효과와 반대 방향의 예상치 못한 반응이거나 그렇지 않으면 현저한 다른 반응입니다. 치과의 국소마취제, 진정제, 카페인, 항히스타민제, 약한 신경경련제, 중추 및 말초 진통제 등 신경활성물질에 대한 반응입니다. 역설적인 반응의 원인은 적어도 부분적으로 유전적이기 때문에, 예를 들어 수술 전과 같은 중요한 상황에서 가족 구성원에게도 그러한 이상이 존재할 수 있는지 묻는 것이 유용할 수 있습니다.[197][198]

진단.

ADHD는 증상에 대한 설명으로 약물, 약물 및 기타 의학적 또는 정신 의학적 문제의 영향을 배제하는 것을 포함하여 사람의 행동 및 정신 발달에 대한 평가에 의해 진단됩니다.[84] ADHD 진단은 대부분의 진단이 교사가 우려를 제기한 후에 시작되는 부모와 교사의[199] 피드백을 고려하는 경우가 많습니다.[171] 그것은 모든 사람들에게 발견되는 하나 이상의 연속적인 인간의 특성의 극단적인 끝이라고 볼 수 있습니다.[200] 뇌에 대한 영상 연구는 개인 간에 일관된 결과를 제공하지 않기 때문에 진단이 아닌 연구 목적으로만 사용됩니다.[201]

북미와 호주에서는 DSM-5 기준을 진단에 사용하고, 유럽 국가들은 ICD-10을 주로 사용합니다. ADHD 진단을 위한 DSM-IV 기준은 ICD-10 기준보다 ADHD 진단 가능성이 3~4배 높습니다.[202] ADHD는 ODD, CD, 반사회적 성격장애와 함께 신경발달장애[203] 또는 파괴적 행동장애로 번갈아 분류됩니다.[204] 진단이 신경학적 장애를 의미하는 것은 아닙니다.[180]

선별해야 하는 관련 질환으로는 불안, 우울증, ODD, CD, 학습 및 언어 장애 등이 있습니다. 고려해야 할 다른 조건으로는 기타 신경발달 장애, 틱 및 수면 무호흡증이 있습니다.[205]

ADHD의 선별 및 평가에는 ADHD 등급 척도, Vanderbilt ADHD 진단 등급 척도와 같은 자가 등급 척도가 사용됩니다.[206] 뇌파검사는 ADHD 진단을 내릴 정도로 정확하지 않습니다.[207][208][209]

분류

진단 및 통계 매뉴얼

다른 많은 정신 질환들과 마찬가지로, 공식적인 진단은 정해진 수의 기준에 따라 자격을 갖춘 전문가에 의해 이루어져야 합니다. 미국에서는 DSM에서 이러한 기준을 미국정신의학회에서 정의하고 있습니다. 2013년에 발표된 DSM-5 기준과 2022년에 발표된 DSM-5-TR 기준을 바탕으로 ADHD의 제시는 세 가지입니다.

- 주로 부주의한 표현인 ADHD는 쉽게 산만해지고, 건망증이 심해지고, 공상에 잠기고, 산만해지고, 주의력이 부족하고, 과제를 완수하는 데 어려움을 겪는 등의 증상을 나타냅니다.

- 주로 과잉행동-충동적 표현인 ADHD는 과도한 안절부절못함, 과잉행동, 그리고 기다리고 앉아있는 것에 대한 어려움을 나타냅니다.

- ADHD, 결합 프레젠테이션은 처음 두 개의 프레젠테이션을 결합한 것입니다.

이 세분화는 부주의, 과잉행동-충동 또는 둘 다의 장기(최소 6개월 지속) 증상 9개 중 최소 6개(어린이) 또는 5개([210]노인 청소년 및 성인)의 존재를 기준으로 합니다.[3][4] 고려하려면 6세에서 12세까지 여러 증상이 나타나야 하며 한 가지 이상의 환경(예: 가정 및 학교 또는 직장)에서 발생해야 합니다. 증상은 해당 연령대의[211] 자녀에게 부적절해야 하며, 이로 인해 사회, 학교 또는 직장과 관련된 문제가 발생한다는 명확한 증거가 있어야 합니다.[212]

DSM-5와 DSM-5-TR은 또한 ADHD 증상이 있지만 완전히 요구 사항을 충족하지 못하는 개인을 위해 두 가지 진단을 제공합니다. Other Specified ADHD는 임상의가 개인이 기준을 충족하지 못하는 이유를 설명할 수 있도록 하는 반면 Unspecified ADHD는 임상의가 이유를 설명하지 않기로 선택하는 경우에 사용됩니다.[3][4]

국제 질병 분류

세계보건기구(WHO)의 국제질병통계분류(ICD-11) 11차 개정에서 이 장애는 주의력결핍 과잉행동장애(코드 6A05)로 분류됩니다. 정의된 하위 유형은 DSM-5의 하위 유형과 유사합니다: 주로 부주의한 프레젠테이션(6A05.0); 주로 과활성-충동 프레젠테이션(6A05.1); 결합 프레젠테이션(6A05.2). 그러나 ICD-11에는 정의된 하위 유형 중 어느 것과도 완전히 일치하지 않는 개인을 위한 두 개의 잔여 범주(기타 지정된 표현(6A05)가 포함되어 있습니다.Y) 임상의가 개인의 프레젠테이션에 대한 세부 정보를 포함하는 경우(6A05).Z) 임상의가 상세한 정보를 제공하지 않는 경우.[5]

제10차 개정(ICD-10)에서, 과운동 장애의 증상은 ICD-11에서 ADHD와 유사했습니다. (ICD-10에 의해 정의된 바와 같이)[59] 전도 장애가 있는 경우, 그 상태를 운동 장애(hyperkinetic conduct disorder)라고 불렀습니다. 그렇지 않으면 활동 및 주의력 장애, 기타 운동 장애 또는 운동 장애로 분류되어 불특정. 후자는 때때로 과잉 운동 증후군으로 언급되었습니다.[59]

사회구성론

ADHD의 사회적 구성 이론은 정상적인 행동과 비정상적인 행동 사이의 경계가 사회적으로 구성되기 때문에(즉, 모든 사회 구성원들, 특히 의사, 부모, 교사 및 다른 사람들에 의해 공동으로 만들어지고 검증되기 때문에), 그런 다음 주관적인 평가와 판단에 따라 어떤 진단 기준이 사용되고 따라서 영향을 받는 사람의 수가 결정됩니다.[213] 이 이론을 지지하는 토마스 스자즈(Thomas Szasz)는 ADHD가 "발명되고 나서 이름이 붙여졌다"고 주장했습니다.[214]

어른들

ADHD를 앓고 있는 성인들은 6세에서 12세 사이에 증상이 나타났을 것이라는 점을 포함하여 같은 기준으로 진단을 받습니다. 개인은 진단에 있어 가장 좋은 정보원이지만, 다른 사람들은 현재와 어린 시절의 증상에 대해 유용한 정보를 제공할 수 있습니다. ADHD의 가족력도 진단에 무게를 더합니다.[55]: 7, 9 ADHD의 핵심 증상은 어린이와 성인에서 비슷하지만, 성인에서는 어린이와 다르게 나타나는 경우가 많습니다. 예를 들어, 어린이에서 볼 수 있는 과도한 신체 활동은 성인에서 불안감과 지속적인 정신 활동으로 나타날 수 있습니다.[55]: 6

전 세계적으로 성인의 2.58%가 지속적인 ADHD(현재 기준을 충족하고 아동기 발병의 증거가 있는 경우)를, 성인의 6.76%가 증상이 있는 ADHD(현재 아동기 발병에 관계없이 ADHD 기준을 충족한다는 의미)를 가지고 있는 것으로 추정됩니다.[215] 2020년에 이는 성인에게 영향을 받은 사람이 각각 1억 3,984만 명, 3억 6,633만 명이었습니다.[215] ADHD 어린이의 약 15%는 25세에 DSM-IV-TR 기준을 계속 충족하고 있으며, 50%는 여전히 일부 증상을 경험하고 있습니다.[55]: 2 2010년[update] 현재 대부분의 성인들은 치료를 받지 않고 있습니다.[216] 진단과 치료가 없는 ADHD를 앓고 있는 많은 성인들은 삶이 흐트러져 있고, 일부는 처방되지 않은 약물이나 알코올을 대처 메커니즘으로 사용합니다.[217] 다른 문제로는 관계와 직업의 어려움, 범죄 활동의 위험 증가 등이 있을 수 있습니다.[218][55]: 6 관련 정신 건강 문제에는 우울증, 불안 장애 및 학습 장애가 포함됩니다.[217]

성인의 일부 ADHD 증상은 어린이에게 나타나는 증상과 다릅니다. ADHD를 앓고 있는 아이들이 과도하게 기어오르고 뛰어놀 수 있는 반면, 성인들은 긴장을 풀 수 없는 상태를 경험하거나 사회적 상황에서 과도하게 이야기할 수 있습니다.[55]: 6 ADHD를 앓고 있는 성인은 충동적으로 관계를 시작하고 감각을 추구하는 행동을 보이며 성질이 급할 수 있습니다.[55]: 6 약물 남용, 도박과 같은 중독적인 행동이 일반적입니다.[55]: 6 이것은 나이가 들면서 DSM-IV 기준이 성장하지 못했다는 것을 보여주는 사람들로 이어졌습니다.[55]: 5–6 DSM-5 기준은 아동기와 비교하여 성인기에 보이는 장애의 차이를 충분히 고려하지 않은 DSM-IV와 달리 성인기를 특별히 다루고 있습니다.[55]: 5

성인의 진단을 위해서는 어릴 때부터 증상이 있어야 합니다. 그럼에도 불구하고 성인기에 ADHD 기준을 충족하는 성인의 비율은 어린 시절 ADHD 진단을 받지 못했을 것입니다. 후기 발병 ADHD의 대부분의 사례는 12-16세 사이에 장애가 발생하므로 초기 성인 또는 청소년 발병 ADHD로 간주될 수 있습니다.[219]

감별진단

| 우울증 | 불안장애 | 조울증 |

|---|---|---|

| 조마조마한 상태로 우울한 상태로

|

DSM은 잠재적인 감별 진단(특정 증상에 대한 잠재적인 대체 설명)을 제공합니다. 어떤 것이 가장 적절한 진단인지는 임상 이력의 평가와 조사에 의해 결정됩니다. DSM-5는 특정 학습 장애, 지적 발달 장애, ASD, 반응성 애착 장애, 불안 장애, 우울증 장애, 양극성 장애 외에도 ODD, 간헐적 폭발 장애, 기타 신경 발달 장애(고정 관념적 운동 장애, 투렛 장애 등)를 제안합니다. 파괴적인 기분 조절 장애, 물질 사용 장애, 성격 장애, 정신병 장애, 약물에 의한 증상, 신경 인지 장애. 이 모든 것이 ADHD의 일반적인 동반 질환은 아니지만 많은 것들이 있습니다.[3] DSM-5-TR은 또한 외상 후 스트레스 장애를 시사합니다.[4]

ADHD는 낮은 기분과 나쁜 자아상, 기분변동, 짜증 등의 증상이 경계성 인격장애뿐만 아니라 디스티미아, 사이클로티미아, 조울증 등과 혼동될 수 있습니다.[55]: 10 불안장애, 인격장애, 발달장애 또는 지적장애로 인한 일부 증상이나 중독, 금단 등 약물남용의 영향이 ADHD와 겹칠 수 있습니다. 이러한 장애는 ADHD와 함께 발생할 수도 있습니다. ADHD형 증상을 유발할 수 있는 질환으로는 갑상샘기능항진증, 발작장애, 납독성, 청력결손, 간질환, 수면무호흡증, 약물 상호작용, 치료되지 않은 셀리악병, 두부손상 등이 있습니다.[221][217][better source needed]

일차적인 수면장애는 주의력과 행동에 영향을 미칠 수 있고 ADHD 증상은 수면에 영향을 미칠 수 있습니다.[222] 따라서 ADHD 어린이는 수면 문제에 대해 정기적으로 평가받는 것이 좋습니다.[223] 아이들의 졸음은 하품과 눈을 비비는 전형적인 증상부터 과잉행동과 부주의에 이르기까지 다양한 증상을 일으킬 수 있습니다. 폐쇄성 수면 무호흡증도 ADHD형 증상을 유발할 수 있습니다.[224]

관리

ADHD 관리에는 일반적으로 상담이나 약물이 단독으로 또는 복합적으로 포함됩니다. 치료는 장기적인 결과를 개선할 수 있지만 부정적인 결과를 완전히 제거하는 것은 아닙니다.[225] 사용되는 약물에는 자극제, 아토목세틴, 알파-2 아드레날린 수용체 작용제, 때로는 항우울제가 포함됩니다.[73][192] 장기적인 보상에 집중하기 어려운 사람들은 많은 양의 긍정적인 강화가 업무 성과를 향상시킵니다.[196] 약물은 [226]가장 효과적인 약물 치료법이지만 부작용이[229] 있을 수 있고 약물 치료를 중단하면 호전이 되돌릴 수 있습니다.[230] ADHD 자극제는 ADHD 어린이의 끈기와 과제 수행 능력도 향상시킵니다.[181][196] 체계적인 리뷰를 인용하자면, "관찰 및 등록부 연구의 최근 증거는 ADHD의 약리학적 치료가 성취도 증가 및 학교 결석 감소, 외상 관련 응급 병원 방문 위험 감소, 자살 및 자살 시도 위험 감소와 관련이 있음을 나타냅니다." 그리고 약물 남용과 범죄율 감소."[231]

행동 치료법

ADHD에서 행동 치료법을 사용하는 것에 대한 좋은 증거가 있습니다. 가벼운 증상이 있거나 미취학 아동에게 권장되는 1차 치료법입니다.[232][233] 사용되는 심리치료법에는 정신교육 투입, 행동치료, 인지행동치료,[234] 대인심리치료, 가족치료, 학교기반 중재, 사회적 기술훈련, 행동 동료 중재, 조직훈련,[235] 부모관리 훈련 등이 있습니다.[180] 뉴로피드백은 치료 후 최대 6개월 및 1년 동안 비활성 대조군보다 더 큰 치료 효과를 가지며, 해당 기간 동안 활성 대조군(임상 효과가 있는 것으로 입증된 대조군)에 필적하는 치료 효과를 가질 수 있습니다.[236] 연구의 효능에도 불구하고 뉴로피드백 관행에 대한 규제가 충분하지 않아 혁신에 대한 비효율적인 적용과 잘못된 주장으로 이어집니다.[237] 부모 교육은 반대 및 비순응 행동을 포함한 여러 행동 문제를 개선할 수 있습니다.[238]

ADHD에 대한 가족 요법의 효과에 대한 양질의 연구는 거의 없지만, 기존의 증거는 그것이 커뮤니티 케어와 비슷하고, 위약보다 낫다는 것을 보여줍니다.[239] ADHD에 특화된 지원 그룹은 정보를 제공하고 가족이 ADHD에 대처하는 데 도움을 줄 수 있습니다.[240]

사회적 기술 훈련, 행동 수정 및 약물 치료는 동료 관계에서 유익한 효과가 제한적일 수 있습니다. 일탈적이지 않은 동료들과의 안정적이고 고품질의 우정은 나중의 심리적 문제로부터 보호합니다.[241]

약

ADHD 약물은 뇌의 전두엽 전 간부, 선조체 및 관련 부위와 네트워크에 영향을 미치며 일반적으로 노르에피네프린과 도파민의 신경 전달을 증가시킴으로써 증상을 완화시키는 것으로 보입니다.[242][243][244]

자극제

메틸페니데이트 및 암페타민 또는 그 유도체는 종종 ADHD의 1차 치료제입니다.[245][246] 처음 시도한 자극제에 약 70%가 반응했고 암페타민과 메틸페니데이트 모두 반응하지 않은 경우는 10%에 불과했습니다.[226] 각성제는 ADHD 어린이가 의도하지 않은 부상을 입을 위험도 줄일 수 있습니다.[247] 자기공명영상 연구에 따르면 암페타민이나 메틸페니데이트를 장기간 사용하면 ADHD 환자에게서 발견되는 뇌 구조와 기능의 이상이 감소합니다.[248][249][250] 2018년 리뷰에 따르면 어린이의 경우 메틸페니데이트, 성인의 경우 암페타민에서 단기적으로 가장 큰 이점이 있는 것으로 나타났습니다.[251] 연구 및 메타 분석에 따르면 암페타민은 증상 감소에 메틸페니데이트보다 약간에서 약간 더 효과적이며,[252][253] α2-아젠다보다[254] ADHD에 더 효과적이지만 메틸페니데이트는 아토목세틴과 같은 비자극제와 비슷한 효능을 가지고 있습니다.

각성제를 복용하는 ADHD 환자의 불면증 발병 가능성은 약에 따라 11~45%로 측정되었으며 중단의 주요 원인이 될 수 있습니다.[255] 틱, 식욕 감소 및 체중 감소 또는 정서적 안정성과 같은 다른 부작용도 중단으로 이어질 수 있습니다.[226] 자극제 정신병과 조증은 치료 용량에서 드물며 암페타민 치료를 시작한 후 처음 몇 주 이내에 약 0.1%의 사람들에게서 발생하는 것으로 보입니다.[256][257][258] 임신 중 이러한 약물의 안전성은 불분명합니다.[259] 약물치료를 중단하면 증상 호전이 지속되지 않습니다.[228][230][260]

ADHD 약물의 장기적인 효과는 아직 완전히 밝혀지지 않았지만 자극제는 일반적으로 어린이와 청소년에게 최대 2년 동안 유익하고 안전합니다.[261][262][263] 2022년 메타 분석에 따르면 ADHD 약물과 심혈관 질환(CVD) 위험 사이에 통계적으로 유의한 연관성이 없는 것으로 나타났지만, 이 연구는 기존 CVD 및 장기 약물 사용 환자에 대한 추가 조사가 필요하다고 제안합니다.[264] 장기간 치료 중인 사람들에게는 정기적인 모니터링이 권장됩니다.[265] 약물치료의 지속적인 필요성을 평가하고, 가능한 성장 지연을 줄이고, 내성을 줄이기 위해 어린이와 청소년을 위한 각성제 치료를 주기적으로 중단해야 한다는 징후가 있습니다.[266][267] ADHD 치료에 사용되는 자극제는 높은 용량에서 잠재적으로 중독성이 [268][269]있지만 남용 가능성이 낮습니다.[245] 자극제를 사용한 치료는 약물 남용을 방지하거나 효과가 없습니다.[55]: 12 [261][268]

ADHD 치료제로서 니코틴을 비롯한 니코틴 작용제에 대한 연구는 대부분 긍정적인 결과를 나타냈지만, 아직까지 ADHD 치료제로 승인된 니코틴 의약품은 없습니다.[270] 카페인은 이전에 ADHD의 2차 치료제로 사용되었지만 연구에 따르면 ADHD 증상을 줄이는 데 큰 효과가 없습니다. 카페인은 주의력, 각성 및 반응 시간에 도움이 되는 것으로 보이지만 ADHD(지속적인 주의력/지속성)와 관련된 부주의 유형은 아닙니다.[271] 유사 에페드린과 에페드린은 ADHD 증상에 영향을 주지 않습니다.[245]

모다피닐은 어린이와 청소년의 ADHD 중증도를 줄이는 데 어느 정도 효과를 보였습니다.[272] ADHD를 치료하기 위해 허가 외로 처방될 수 있습니다.

비자극제

두 가지 비자극제인 아토목세틴과 빌록사진은 ADHD 치료를 위해 FDA와 다른 국가에서 승인을 받았습니다.

아토목세틴은 중독성이 없기 때문에 레크리에이션 또는 강제 자극제 사용의 위험이 있는 사람들에게 선호될 수 있지만, 이러한 이유로 자극제보다 아토목세틴의 사용을 뒷받침할 증거가 부족합니다.[55]: 13 아토목세틴은 노르에피네프린 재흡수를 통해 ADHD 증상을 완화하고, 전전두엽 피질에서[244] 간접적으로 도파민을 증가시켜 뇌 영역의 70-80%를 자극제와 공유하여 생성된 효과를 나타냅니다.[243] 아토목세틴은 학업 성적을 크게 향상시키는 것으로 나타났습니다.[273][274] 메타 분석 및 체계적인 검토 결과 아톰옥세틴은 소아 및 청소년에서 메틸페니데이트와 유사한 효능, 동등한 내약성 및 반응률(75%)을 갖는 것으로 나타났습니다. 성인의 경우 효능과 중단률이 동등합니다.[275][276][277][278]

임상 시험 데이터 분석에 따르면 빌록사진은 아토목세틴과 메틸페니데이트만큼 효과적이지만 부작용은 적습니다.[279]

아만타딘은 메틸페니데이트로 치료받은 어린이에서 유사한 개선을 유도하는 것으로 나타났으며, 부작용은 덜 빈번했습니다.[280] 2021년 후향적 연구에 따르면 아만타딘은 ADHD 관련 증상에 대한 자극제에 효과적인 보조제 역할을 할 수 있으며 2세대 또는 3세대 항정신병 약물에 대한 더 안전한 대안으로 보입니다.[281]

부프로피온은 또한 연구 결과로 인해 일부 임상의들에 의해 라벨 외로 사용됩니다. 효과적이지만 아토목세틴과 메틸페니데이트보다는 약간 적습니다.[282]

약물이 사회적 행동에 미치는 영향에 대한 증거는 거의 없습니다.[283] 항정신병약은 ADHD의 공격성 치료에도 사용될 수 있습니다.[284]

알파-2a 작용제

두 가지 알파-2a 작용제, 구아파신과 클로니딘의 확장 방출 제형은 ADHD 치료를 위해 FDA 및 다른 국가에서 승인되었습니다(어린이 및 청소년에게 효과적이지만 성인에게는 여전히 효과가 나타나지 않았습니다).[285][286] 그들은 증상을 줄이는 데 자극제(암페타민 및 메틸페니데이트) 및 비자극제(아토목세틴 및 빌록사진)보다 약간 덜 효과적인 것으로 보이지만 [287][288]유용한 대안이 되거나 자극제와 함께 사용될 수 있습니다. 이들 약물은 전방 간부망에서 노르아드레날린 신경세포 바깥쪽의 알파-2a 포트를 조절하는 방식으로 작용하기 때문에 정보(전기신호)가 노이즈에 덜 교란됩니다.[289]

가이드라인

의약품 사용 시기에 대한 지침은 국가별로 다릅니다. 영국 국립보건의료우수연구소는 중증의 경우에만 어린이에게 사용할 것을 권고하고 있지만, 성인에게는 약물치료가 일차적인 치료법입니다.[290] 반대로, 대부분의 미국 지침은 대부분의 연령대에서 약물을 권장합니다.[291] 특히 미취학 아동에게는 약물을 권장하지 않습니다.[290][180] 자극제의 과소 투여는 발생할 수 있으며, 반응이 부족하거나 나중에 효과가 상실될 수 있습니다.[292] 이는 특히 청소년과 성인에서 흔히 발생하는데, 승인된 투여량이 학령기 어린이를 기반으로 하기 때문에 일부 시술자가 체중 기반 또는 급여 기반의 허가 외 투여를 대신 사용하게 됩니다.[293][294][295]

운동

규칙적인 신체 운동, 특히 유산소 운동은 어린이와 성인의 ADHD에 대한 효과적인 추가 치료법이며, 특히 자극제 약물과 결합할 때 더욱 그렇습니다(현재 증상 개선을 위한 최상의 강도와 유산소 운동 유형은 알려져 있지 않습니다).[296] ADHD 개인의 규칙적인 유산소 운동의 장기적인 효과에는 더 나은 행동과 운동 능력, 향상된 실행 기능(다른 인지 영역 중 주의 집중, 억제 제어 및 계획 포함), 더 빠른 정보 처리 속도 및 더 나은 기억력이 포함됩니다.[297] 규칙적인 유산소 운동에 대한 반응으로 행동 및 사회 정서적 결과에 대한 부모-교사 평가는 다음과 같습니다: 전반적인 기능 향상, ADHD 증상 감소, 자존감 향상, 불안 및 우울증 감소, 신체 불만 감소, 학업 및 교실 행동 개선, 사회적 행동 개선. 자극제 약물을 복용한 상태에서 운동을 하면 자극제 약물이 실행 기능에 미치는 영향이 증가합니다.[298] 이러한 운동의 단기적인 효과는 뇌에서 시냅스 도파민과 노르에피네프린의 증가에 의해 매개된다고 믿어집니다.[298]

다이어트

2019년[update] 현재 미국소아과학회, 국립보건의료우수연구원, 보건의료연구품질원에서는 근거가 부족하여 식이수정을 권장하지 않습니다.[299][290] 2013년 메타 분석에 따르면 ADHD 어린이의 3분의 1 미만이 지방산을 무료로 보충하거나 인공 식품 착색제 섭취를 줄이면 증상이 다소 개선되는 것으로 나타났습니다.[160] 이러한 혜택은 음식에 민감한 어린이나 ADHD 약물 치료를 동시에 받고 있는 어린이에게 제한될 수 있습니다.[160] 이 리뷰는 또한 ADHD를 치료하기 위해 식단에서 다른 음식을 제거하는 것을 지지하는 증거가 없다는 것을 발견했습니다.[160] 2014년 리뷰에 따르면 식단을 제거하면 알레르기가 있는 아이들과 같은 소수의 아이들에게 전체적으로 작은 이점이 생긴다고 합니다.[175] 2016년 리뷰에 따르면 글루텐이 없는 식단을 표준 ADHD 치료제로 사용하는 것은 권장되지 않습니다.[221] 2017년 리뷰에 따르면 몇 가지 음식을 제거하는 식단은 너무 어려서 약을 먹지 못하거나 약에 반응하지 않는 어린이에게 도움이 될 수 있는 반면, 표준 ADHD 치료법으로 무료 지방산 보충이나 인공 식품 착색 섭취 감소는 권장되지 않습니다.[300] 철분, 마그네슘, 요오드의 만성 결핍은 ADHD 증상에 부정적인 영향을 미칠 수 있습니다.[301] 낮은 조직 아연 수치가 ADHD와 관련이 있을 수 있다는 적은 양의 증거가 있습니다.[302] 입증된 아연 결핍이 없는 경우(개발도상국 이외에서는 드문 경우), 아연 보충은 ADHD 치료제로 권장되지 않습니다.[303] 그러나 아연 보충제는 ADHD 치료를 위해 암페타민과 함께 사용할 경우 암페타민의 최소 유효 용량을 줄일 수 있습니다.[304]

예후

ADHD는 성인이 될 때까지 지속되는 경우가 약 30-50%입니다.[305] 영향을 받은 사람들은 성숙하면서 대처 메커니즘이 발달하여 이전 증상을 어느 정도 보상할 가능성이 높습니다.[217] ADHD를 앓고 있는 어린이는 의도하지 않은 부상의 위험이 더 높습니다.[247] 약물이 기능 장애와 삶의 질에 미치는 영향(예: 사고 위험 감소)은 여러 영역에서 발견되었습니다.[306] ADHD를 앓고 있는 사람들의 흡연율은 약 40%[307]로 일반 인구보다 높습니다.

DSM-IV 기준을 통해 진단할 경우 약 5-7%의 어린이에게 영향을 미치고,[308] ICD-10 기준을 통해 진단할 경우 1-2%의 어린이에게 영향을 미칩니다.[309] 요금은 국가 간에 비슷하고 요금 차이는 대부분 진단 방법에 따라 다릅니다.[310] ADHD는 증상이 진단 기준과 다르기 때문에 소녀에게서 간과되거나 나중에 진단되지만, ADHD는 남자에서 여자보다 약 2배,[4][308] 남자에서 1.6배 더 자주 진단됩니다.[4][314] 소아기 진단을 받은 사람의 약 30-50%가 성인기에 ADHD를 계속 앓고 있으며, 성인의 2.58%가 소아기에 시작된 ADHD를 앓고 있는 것으로 추정됩니다.[215][315][text–source integrity?] 성인의 경우 과잉행동은 대개 내면의 불안함으로 대체되며, 성인은 자신의 장애를 보완하기 위한 대처 능력을 키우는 경우가 많습니다. 이 상태는 정상적인 행동 범위 내에서 높은 수준의 활동뿐만 아니라 다른 상태와 구별하기 어려울 수 있습니다. ADHD는 환자의 건강과 관련된 삶의 질에 부정적인 영향을 미치며, 이는 불안과 우울증과 같은 다른 정신 질환에 의해 더욱 악화되거나 위험을 증가시킬 수 있습니다.[231]

ADHD를 앓고 있는 사람은 교도소 인구에서 현저하게 과대 표현됩니다. 수감자들 사이에서 ADHD 유병률에 대한 일반적으로 받아들여지는 추정치는 없지만, 2015년 메타 분석에서는 25.5%의 유병률을 추정했으며, 더 큰 2018년 메타 분석에서는 26.2%[316]의 빈도를 추정했습니다. ADHD는 장기 수감자들 사이에서 더 흔합니다. 스웨덴의 보안이 철저한 교도소인 Norrtälje 교도소의 2010년 연구에 따르면 ADHD 유병률은 40%[317]로 추정됩니다.

역학

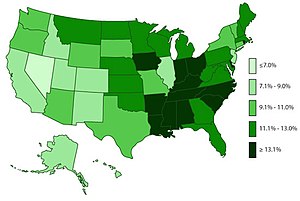

ADHD는 DSM-IV 기준을 통해 진단했을 때 18세 이하의 사람들 중 약 6-7%에게 영향을 미치는 것으로 추정됩니다.[308] ICD-10 기준을 통해 진단하면 이 연령대의 비율은 약 1-2%[309]로 추정됩니다. ADHD는 북미 어린이가 아프리카와 중동 어린이보다 더 높은 것으로 나타나는데, 이는 기본적인 빈도의 차이라기보다는 진단 방법이 다르기 때문인 것으로 판단됩니다.[319][verification needed] 2019년 [update]기준으로 전 세계적으로 8,470만 명에게 영향을 미치는 것으로 추정됩니다.[2] 동일한 진단 방법을 사용하는 경우 국가 간에 비율이 비슷합니다.[310] ADHD는 남아가 여아보다 약 3배 더 자주 진단됩니다.[313][202] 이것은 기저율의 진정한 차이 또는 ADHD를 앓고 있는 여성과 소녀가 진단을 받을 가능성이 적다는 것을 반영할 수 있습니다.[320] 여러 나라의 연구에 따르면 학년 초에 가까운 곳에서 태어난 아이들은 나이가 많은 학급 친구들보다 ADHD 진단을 받고 약물 치료를 받는 경우가 더 많다고 합니다.[321]

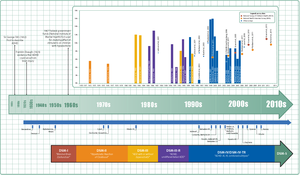

1970년대 이후 영국과 미국에서 진단 및 치료 비율이 증가했습니다. 1970년 이전에는 어린이가 ADHD 진단을 받는 경우가 드물었지만 1970년대에는 약 1%[322]의 비율을 보였습니다. 이는 질병의 일반적인 상태에 대한 진정한 변화라기보다는 질병을[323] 진단하는 방법과 사람들이 약물로 쉽게 치료할 수 있는 방법의 변화에 주로 기인하는 것으로 생각됩니다.[309] 2013년 DSM-5의 출시와 함께 진단 기준을 변경하면 특히 성인들 사이에서 ADHD 진단을 받은 사람들의 비율이 증가할 것으로 믿어졌습니다.[324]

백인과 비백인 인구 사이의 ADHD에 대한 치료와 이해의 차이로 인해 많은 비백인 어린이들이 진단되지 않고 약을 복용하지 않습니다.[325] 미국 내에서 ADHD에 대한 백인과 비백인의 이해 사이에 종종 차이가 있는 것으로 나타났습니다. 이로 인해 ADHD의 증상 분류에 차이가 발생하여 오진을 하게 되었습니다. 또한 비백인 가정과 교사들은 ADHD의 증상을 정신질환이 아닌 행동 문제로 이해하는 것이 일반적인 것으로 나타났습니다.

ADHD 진단의 문화 간 차이는 유해하고 인종적으로 표적화된 의료 행위의 오래 지속되는 영향에도 기인할 수 있습니다. 의료 유사 과학, 특히 미국 노예 제도 기간 동안 아프리카계 미국인을 대상으로 한 과학은 특정 지역 사회 내에서 의료 행위에 대한 불신으로 이어집니다. ADHD 증상이 정신과적인 상태가 아닌 잘못된 행동으로 간주되는 경우가 많고, ADHD를 조절하기 위해 약물을 사용하는 경우 ADHD 진단을 신뢰하는 데 주저하게 됩니다. 비백인 개인에 대한 고정관념으로 인해 ADHD에서 오진이 발생할 수도 있습니다. ADHD는 주관적으로 결정되는 증상으로 인해 의료 전문가는 백인과 비백인 간의 증상 발현 차이로 인해 정형화된 행동을 기반으로 개인을 진단하거나 오진할 수 있습니다.[326]

역사

과잉행동은 오랫동안 인간 상태의 일부였습니다. 알렉산더 크라이튼 경은 1798년에 쓰여진 그의 책 정신착란의 본질과 기원에 대한 탐구에서 "정신적 불안정"을 묘사합니다.[327][328] 그는 아이들이 주의를 기울이지 않고 "피젯"을 가지고 있는 징후를 보이는 것에 대해 관찰했습니다. ADHD에 대한 최초의 명확한 설명은 1902년 조지 스틸이 런던 왕립 의사 대학에서 연 일련의 강의에서 공을 세웠습니다.[329][323] 그는 자연과 양육 모두가 이 장애에 영향을 미칠 수 있다고 지적했습니다.

ADHD는 1980년부터 1987년까지 공식적으로 주의력결핍장애(ADD)로 알려졌습니다. 1980년대 이전에는 아동기의 운동신경 과잉반응으로 알려졌습니다. ADHD와 유사한 증상은 18세기로 거슬러 올라가는 의학 문헌에서 설명되었습니다.

Alfred Tredgold는 1917년부터 1928년까지 뇌염 무기력증 유행에 의해 검증될 수 있었던 뇌 손상과 행동 또는 학습 문제 사이의 연관성을 제안했습니다.[330][331][332]

이 질환을 설명하는 데 사용되는 용어는 시간이 지남에 따라 바뀌었으며 DSM-I(1952)의 최소 뇌 기능 장애, DSM-II(1968)의 어린 시절의 과운동 반응, DSM-III(1980)의 과활성 유무에 관계없이 주의력 결핍 장애를 포함했습니다.[323] 이는 1987년 DSM-III-R에서 ADHD로 변경되었고, 1994년 DSM-IV에서 ADHD 무주의형, ADHD 과활성-충동형, ADHD 결합형의 세 가지 하위 유형으로 진단을 나누었습니다.[333] 이 용어는 2013년 DSM-5, 2022년 DSM-5-TR에 유지되었습니다.[3][4] DSM 이전에는 1930년대에 최소한의 뇌 손상을 포함하는 용어가 있었습니다.[334]

1934년 벤제드린은 미국에서 사용이 승인된 최초의 암페타민 의약품이 되었습니다.[335] 메틸페니데이트는 1950년대에, 에난티오퓨어 덱스트로암페타민은 1970년대에 도입되었습니다.[323] ADHD를 치료하기 위해 자극제를 사용하는 것은 1937년에 처음 기술되었습니다.[336] 찰스 브래들리(Charles Bradley)는 행동 장애를 가진 아이들에게 벤제드린(Benzedrine)을 주었고, 그것이 학업 수행 능력과 행동을 향상시킨다는 것을 발견했습니다.[337][338]

일단 신경 영상 연구가 가능해지자, 1990년대에 수행된 연구들은 신경학적 차이들, 특히 전두엽에서의 신경학적 차이들이 ADHD에 관련되어 있다는 기존의 이론을 뒷받침했습니다. 같은 기간 동안, 유전적인 요소가 확인되었고 ADHD는 어린 시절부터 성인기까지 지속되는 지속적이고 장기적인 장애로 인정되었습니다.[339][340]

ADHD는 Lahey와 동료들에 의해 완성된 현장 시험 때문에 현재 세 가지 하위 유형으로 나뉘었습니다.[341]

논란

ADHD, 그 진단 및 치료법은 1970년대부터 논란이 되어 왔습니다.[230][6] 논란에는 임상의, 교사, 정책 입안자, 부모 및 언론이 포함됩니다. ADHD가 정상적인 행동[84][342] 범위 안에 있다는 견해부터 ADHD가 유전적인 상태라는 가설까지 입장이 다양합니다.[343] 이 밖에 어린이들의 각성제 사용,[230] 진단 방법, 과잉 진단 가능성 등이 논란의 대상이 되고 있습니다.[344] 2009년 국립보건의료우수연구원은 논란을 인정하면서도 현재의 치료법과 진단 방법은 학계의 지배적인 견해에 따른 것이라고 밝히고 있습니다.[200] 2014년, 장애를 인식하는 초기 옹호자 중 한 명인 키스 코너스(Keith Conners)는 뉴욕 타임즈(New York Times) 기사에서 과잉 진단에 반대하는 목소리를 냈습니다.[345] 대조적으로, 2014년 동료 평가 의학 문헌 검토에 따르면 ADHD는 성인에서 과소 진단되었습니다.[315]

ADHD 진단은 생물학적 검사에 근거하지 않아 주관적이라는 비판을 받아왔습니다. ADHD에 관한 국제 합의 성명서는 ADHD가 Robins와 Guze에 의해 확립된 정신 질환의 유효성에 대한 표준 기준을 충족한다는 근거에 기초하여 이러한 비판이 근거가 없다고 결론 내렸습니다. 그들은 다음과 같은 이유로 이 장애가 유효하다고 간주된다는 것을 증명합니다. 1) 다양한 환경과 문화에서 잘 훈련된 전문가들이 잘 정의된 기준을 사용하여 장애의 유무에 대해 동의하고 2) 진단이 환자가 가질 수 있는 추가적인 문제(예: a)를 예측하는 데 유용하기 때문입니다. 학교에서 학습하는 어려움), b) 미래의 환자 결과(예: 미래의 약물 남용 위험), c) 치료에 대한 반응(예: 약물 및 심리 치료), d) 장애에 대한 일관된 원인 세트를 나타내는 특징(예: 유전학 또는 뇌 영상에서 얻은 결과). 전문 협회는 ADHD 진단을 위한 가이드라인을 승인하고 발표했습니다.[346]

국가, 국가 내 주, 인종 및 민족에 따라 진단 비율이 크게 다르기 때문에 ADHD 증상의 존재 이외의 일부 의심 요소가 문화 규범과 같이 진단에 역할을 하고 있습니다.[347][348] 일부 사회학자들은 ADHD를 일탈 행동의 의학화, 즉 이전에 비의학적이었던 학교 수행 문제가 의학화되는 사례로 간주합니다.[349] 대부분의 의료 제공자들은 ADHD를 최소한 심각한 증상을 보이는 소수의 사람들에게서 진정한 장애로 받아들입니다. 의료 제공자들 사이에서 논쟁은 주로 가벼운 증상을 가진 훨씬 더 많은 사람들의 진단과 치료에 초점을 맞추고 있습니다.[171][350][351]

ADHD 치료의 바람직한 평가변수의 성격과 범위는 ADHD의 진단 기준마다 다릅니다.[352] 대부분의 연구에서 치료의 효능은 ADHD 증상의 감소에 의해 결정됩니다.[353] 그러나 일부 연구는 ADHD 치료 효과에 대한 평가의 일부로 교사와 학부모의 주관적인 평가를 포함했습니다.[354] 이에 비해 ADHD 치료를 받고 있는 아동의 주관적 등급은 ADHD 치료의 효과를 평가하는 연구에 거의 포함되지 않습니다.

학령기 아동의 생일 진단 패턴에 눈에 띄는 차이가 있었습니다. 교실 환경에서 다른 사람들보다 학교 시작 연령보다 상대적으로 더 젊게 태어난 사람들은 ADHD 진단을 받을 가능성이 더 높은 것으로 나타났습니다. 학령기가 31년 12월에 태어난 남자아이들은 1월에 태어난 남자아이들보다 진단을 받을 확률이 30%, 치료를 받을 확률이 41% 높은 것으로 나타났습니다. 12월에 태어난 여아는 다음 달에 태어난 여아보다 진단율이 70%, 치료율이 77% 더 높았습니다. 역년의 마지막 3일에 태어난 아이들이 역년의 첫 3일에 태어난 아이들에 비해 ADHD 진단과 치료 수준이 현저히 높은 것으로 보고되었습니다. 이 연구들은 ADHD 진단이 주관적으로 분석되기 쉽다는 것을 시사합니다.[348]

연구방향

긍정적인 특성 가능성

ADHD의 가능한 긍정적인 특성은 새로운 연구 방법이므로 제한적입니다.

2020년 리뷰에 따르면 창의성은 ADHD 증상, 특히 다양한 사고와 창의적 성취의 양과 관련이 있을 수 있지만 ADHD 자체의 장애와는 관련이 없는 것으로 나타났습니다. 즉, ADHD 진단을 받은 사람에게서는 창의성이 증가하지 않는 것으로 나타났습니다. 무증상 증상이 있거나 장애와 관련된 특성이 있는 사람에게만 해당됩니다. 발산적 사고는 서로 크게 다른 창의적인 해결책을 만들어내고 다양한 관점에서 문제를 고려하는 능력입니다. ADHD 증상을 가진 사람들은 주의를 분산시키고, 고려 중인 과제의 측면 간에 빠른 전환을 가능하게 하는 경향이 있기 때문에 이러한 형태의 창의성에 유리할 수 있습니다. 유연한 연상 기억, 창의성과 관련된 더 멀리 관련된 아이디어를 기억하고 사용할 수 있는 유연한 연상 기억, 그리고 충동성. ADHD 증상을 가진 사람들이 다른 사람들이 가지고 있지 않을 수도 있는 아이디어를 고려하게 만듭니다. 그러나 ADHD를 앓고 있는 사람들은 수렴적 사고로 어려움을 겪을 수 있습니다. 이는 분명히 관련된 지식의 집합이 문제에 대해 인식된 최상의 단일 해결책에 도달하기 위한 집중된 노력으로 사용되는 인지 과정입니다.[355]

2020년 기사에 따르면 역사적 문서는 레오나르도 다빈치가 ADHD의 특징으로 미루기와 시간 관리의 어려움을 뒷받침했으며, 그는 계속해서 일을 하고 있지만 종종 이 일에서 저 일로 뛰어다닌다고 합니다.[356]

진단을 위한 가능한 바이오마커

ADHD 바이오마커에 대한 리뷰에 따르면 혈소판 모노아민 산화효소 발현, 소변 노르에피네프린, 소변 MHPG 및 소변 페닐아민 수치는 ADHD 개인과 비ADHD 대조군 간에 일관되게 다릅니다. 이러한 측정은 잠재적으로 ADHD의 진단 바이오마커 역할을 할 수 있지만 진단적 유용성을 확립하기 위해서는 더 많은 연구가 필요합니다. 소변 및 혈장 페닐아민 농도는 ADHD 개인에서 대조군에 비해 낮고 ADHD에 대해 가장 일반적으로 처방되는 두 가지 약물인 암페타민 및 메틸페니데이트는 ADHD 치료 반응이 있는 개인에서 페닐아민 생합성을 증가시킵니다.[154] 낮은 소변 페닐아민 농도는 ADHD 개인의 부주의 증상과도 관련이 있습니다.[357]

참고 항목

- 사고성 § 저공포증

- 자가투여

- 주의력 피로(directed attention featory) – ADHD의 많은 증상을 공유하는 일시적인 상태

참고문헌

- ^ Young K (9 February 2017). "Anxiety or ADHD? Why They Sometimes Look the Same and How to Tell the Difference". Hey Sigmund. Archived from the original on 26 January 2023. Retrieved 27 January 2023.

- ^ a b Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (17 October 2020). "Global Burden of Disease Study 2019: Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder—Level 3 cause" (PDF). The Lancet. 396 (10258). Table 1. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 January 2021. Retrieved 7 January 2021.DSM-IV-TR 및 ICD-10 기준이 Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (17 October 2020). "Global Burden of Disease Study 2019: Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder—Level 3 cause" (PDF). The Lancet. 396 (10258). Table 1. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 January 2021. Retrieved 7 January 2021.모두 사용되었습니다.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed.). Arlington: American Psychiatric Publishing. 2013. pp. 59–65. ISBN 978-0-89042-555-8.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, Text Revision (DSM-5-TR). Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Publishing. February 2022. ISBN 978-0-89042-575-6. OCLC 1288423302.

- ^ a b c "6A05 Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder". International Classification of Diseases 11th Revision. February 2022 [2019]. Archived from the original on 1 August 2018. Retrieved 8 May 2022.

- ^ a b Foreman DM (February 2006). "Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: legal and ethical aspects". Archives of Disease in Childhood. 91 (2): 192–194. doi:10.1136/adc.2004.064576. PMC 2082674. PMID 16428370.

- ^ a b c d Faraone SV, Banaschewski T, Coghill D, Zheng Y, Biederman J, Bellgrove MA, et al. (September 2021). "The World Federation of ADHD International Consensus Statement: 208 Evidence-based conclusions about the disorder". Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 128. Elsevier BV: 789–818. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2021.01.022. PMC 8328933. PMID 33549739.

- ^ [3][4][5][6][7]

- ^ Pievsky MA, McGrath RE (March 2018). "The Neurocognitive Profile of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder: A Review of Meta-Analyses". Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology. 33 (2): 143–157. doi:10.1093/arclin/acx055. PMID 29106438.

- ^ Schoechlin C, Engel RR (August 2005). "Neuropsychological performance in adult attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: meta-analysis of empirical data". Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology. 20 (6): 727–744. doi:10.1016/j.acn.2005.04.005. PMID 15953706.

- ^ Hart H, Radua J, Nakao T, Mataix-Cols D, Rubia K (February 2013). "Meta-analysis of functional magnetic resonance imaging studies of inhibition and attention in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: exploring task-specific, stimulant medication, and age effects". JAMA Psychiatry. 70 (2): 185–198. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.277. PMID 23247506.

- ^ a b Hoogman M, Muetzel R, Guimaraes JP, Shumskaya E, Mennes M, Zwiers MP, et al. (July 2019). "Brain Imaging of the Cortex in ADHD: A Coordinated Analysis of Large-Scale Clinical and Population-Based Samples". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 176 (7): 531–542. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2019.18091033. PMC 6879185. PMID 31014101.

- ^ a b c d Brown TE (October 2008). "ADD/ADHD and Impaired Executive Function in Clinical Practice". Current Psychiatry Reports. 10 (5): 407–411. doi:10.1007/s11920-008-0065-7. PMID 18803914. S2CID 146463279.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Malenka RC, Nestler EJ, Hyman SE (2009). "Chapter 6: Widely Projecting Systems: Monoamines, Acetylcholine, and Orexin". In Sydor A, Brown RY (eds.). Molecular Neuropharmacology: A Foundation for Clinical Neuroscience (2nd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. pp. 148, 154–157. ISBN 978-0-07-148127-4.

DA has multiple actions in the prefrontal cortex. It promotes the 'cognitive control' of behavior: the selection and successful monitoring of behavior to facilitate attainment of chosen goals. Aspects of cognitive control in which DA plays a role include working memory, the ability to hold information 'on line' in order to guide actions, suppression of prepotent behaviors that compete with goal-directed actions, and control of attention and thus the ability to overcome distractions. Cognitive control is impaired in several disorders, including attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. ... Noradrenergic projections from the LC thus interact with dopaminergic projections from the VTA to regulate cognitive control. ... it has not been shown that 5HT makes a therapeutic contribution to treatment of ADHD.

- ^ a b Diamond A (2013). "Executive functions". Annual Review of Psychology. 64: 135–168. doi:10.1146/annurev-psych-113011-143750. PMC 4084861. PMID 23020641.

EFs and prefrontal cortex are the first to suffer, and suffer disproportionately, if something is not right in your life. They suffer first, and most, if you are stressed (Arnsten 1998, Liston et al. 2009, Oaten & Cheng 2005), sad (Hirt et al. 2008, von Hecker & Meiser 2005), lonely (Baumeister et al. 2002, Cacioppo & Patrick 2008, Campbell et al. 2006, Tun et al. 2012), sleep deprived (Barnes et al. 2012, Huang et al. 2007), or not physically fit (Best 2010, Chaddock et al. 2011, Hillman et al. 2008). Any of these can cause you to appear to have a disorder of EFs, such as ADHD, when you do not.

- ^ a b c d e Antshel KM, Hier BO, Barkley RA (2014). "Executive Functioning Theory and ADHD". In Goldstein S, Naglieri JA (eds.). Handbook of Executive Functioning. New York, NY: Springer. pp. 107–120. doi:10.1007/978-1-4614-8106-5_7. ISBN 978-1-4614-8106-5.

- ^ [9][10][11][12][13][14][15][16]

- ^ a b Retz W, Stieglitz RD, Corbisiero S, Retz-Junginger P, Rösler M (October 2012). "Emotional dysregulation in adult ADHD: What is the empirical evidence?". Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics. 12 (10): 1241–1251. doi:10.1586/ern.12.109. PMID 23082740. S2CID 207221320.

- ^ a b Faraone SV, Rostain AL, Blader J, Busch B, Childress AC, Connor DF, et al. (February 2019). "Practitioner Review: Emotional dysregulation in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder - implications for clinical recognition and intervention". Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines. 60 (2): 133–150. doi:10.1111/jcpp.12899. PMID 29624671.

- ^ Shaw P, Stringaris A, Nigg J, Leibenluft E (March 2014). "Emotion dysregulation in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 171 (3): 276–293. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.13070966. PMC 4282137. PMID 24480998.

- ^ [18][19][20][19]

- ^ Fleming M, Fitton CA, Steiner MF, McLay JS, Clark D, King A, et al. (July 2017). "Educational and Health Outcomes of Children Treated for Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder". JAMA Pediatrics. 171 (7): e170691. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.0691. PMC 6583483. PMID 28459927.

- ^ Lee YC, Yang HJ, Chen VC, Lee WT, Teng MJ, Lin CH, et al. (1 April 2016). "Meta-analysis of quality of life in children and adolescents with ADHD: By both parent proxy-report and child self-report using PedsQL™". Research in Developmental Disabilities. 51–52: 160–172. doi:10.1016/j.ridd.2015.11.009. PMID 26829402.

- ^ Barkley RA, Fischer M (July 2019). "Hyperactive Child Syndrome and Estimated Life Expectancy at Young Adult Follow-Up: The Role of ADHD Persistence and Other Potential Predictors". Journal of Attention Disorders. 23 (9): 907–923. doi:10.1177/1087054718816164. PMID 30526189. S2CID 54472439.

- ^ Cattoi B, Alpern I, Katz JS, Keepnews D, Solanto MV (April 2022). "The Adverse Health Outcomes, Economic Burden, and Public Health Implications of Unmanaged Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD): A Call to Action Resulting from CHADD Summit, Washington, DC, October 17, 2019". Journal of Attention Disorders. 26 (6): 807–808. doi:10.1177/10870547211036754. PMID 34585995. S2CID 238218526.

- ^ "'A horrible, perfect storm': Frustrations rise as shortage of Adderall, other ADHD medication continues". Chicago Tribune. 12 February 2024. Retrieved 16 February 2024.

- ^ a b Barkley RA, Murphy KR (1 June 2011). "The Nature of Executive Function (EF) Deficits in Daily Life Activities in Adults with ADHD and Their Relationship to Performance on EF Tests". Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 33 (2): 137–158. doi:10.1007/s10862-011-9217-x. ISSN 1573-3505.

- ^ Groen Y, Priegnitz U, Fuermaier AB, Tucha L, Tucha O, Aschenbrenner S, et al. (December 2020). "Testing the relation between ADHD and hyperfocus experiences". Research in Developmental Disabilities. 107: 103789. doi:10.1016/j.ridd.2020.103789. PMID 33126147.

- ^ "APA PsycNet". psycnet.apa.org. Retrieved 3 March 2024.

- ^ Ashinoff BK, Abu-Akel A (February 2021). "Hyperfocus: the forgotten frontier of attention". Psychological Research. 85 (1): 1–19. doi:10.1007/s00426-019-01245-8. PMC 7851038. PMID 31541305.

- ^ Ishii S, Takagi S, Kobayashi N, Jitoku D, Sugihara G, Takahashi H (16 March 2023). "Hyperfocus symptom and internet addiction in individuals with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder trait". Frontiers in Psychiatry. 14: 1127777. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1127777. PMC 10061009. PMID 37009127.

- ^ Worthington R, Wheeler S (January 2023). "Hyperfocus and offending behaviour: a systematic review" (PDF). The Journal of Forensic Practice. 25 (3): 185–200. doi:10.1108/JFP-01-2022-0005. ISSN 2050-8794. S2CID 258330884.

- ^ Larsson H, Anckarsater H, Råstam M, Chang Z, Lichtenstein P (January 2012). "Childhood attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder as an extreme of a continuous trait: a quantitative genetic study of 8,500 twin pairs". Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines. 53 (1): 73–80. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2011.02467.x. PMID 21923806.

- ^ Lee SH, Ripke S, Neale BM, Faraone SV, Purcell SM, Perlis RH, et al. (September 2013). "Genetic relationship between five psychiatric disorders estimated from genome-wide SNPs". Nature Genetics. 45 (9): 984–994. doi:10.1038/ng.2711. PMC 3800159. PMID 23933821.

- ^ Cecil CA, Nigg JT (November 2022). "Epigenetics and ADHD: Reflections on Current Knowledge, Research Priorities and Translational Potential". Molecular Diagnosis & Therapy. 26 (6): 581–606. doi:10.1007/s40291-022-00609-y. PMC 7613776. PMID 35933504.

- ^ Nigg JT, Sibley MH, Thapar A, Karalunas SL (December 2020). "Development of ADHD: Etiology, Heterogeneity, and Early Life Course". Annual Review of Developmental Psychology. 2 (1): 559–583. doi:10.1146/annurev-devpsych-060320-093413. PMC 8336725. PMID 34368774.

- ^ a b "APA PsycNet". psycnet.apa.org. Retrieved 28 March 2024.

- ^ a b c d e "Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (Easy-to-Read)". National Institute of Mental Health. 2013. Archived from the original on 14 April 2016. Retrieved 17 April 2016.

- ^ Franke B, Michelini G, Asherson P, Banaschewski T, Bilbow A, Buitelaar JK, et al. (October 2018). "Live fast, die young? A review on the developmental trajectories of ADHD across the lifespan". European Neuropsychopharmacology. 28 (10): 1059–1088. doi:10.1016/j.euroneuro.2018.08.001. PMC 6379245. PMID 30195575.

- ^ Faraone SV, Asherson P, Banaschewski T, Biederman J, Buitelaar JK, Ramos-Quiroga JA, et al. (August 2015). "Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder" (PDF). Nature Reviews. Disease Primers. 1: 15020. doi:10.1038/nrdp.2015.20. PMID 27189265. S2CID 7171541.

- ^ "Traumatic Brain Injury - an overview ScienceDirect Topics". www.sciencedirect.com. Retrieved 4 March 2024.

- ^ a b "The Connection between Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI) and Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder, Therapeutic Approaches". Retrieved 29 March 2024.

- ^ Eme R (April 2012). "ADHD: an integration with pediatric traumatic brain injury". Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics. 12 (4): 475–483. doi:10.1586/ern.12.15. PMID 22449218. S2CID 35718630.

- ^ Faraone SV, Larsson H (April 2019). "Genetics of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder". Molecular Psychiatry. 24 (4): 562–575. doi:10.1038/s41380-018-0070-0. PMC 6477889. PMID 29892054.

- ^ Kennedy M, Kreppner J, Knights N, Kumsta R, Maughan B, Golm D, et al. (October 2016). "Early severe institutional deprivation is associated with a persistent variant of adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: clinical presentation, developmental continuities and life circumstances in the English and Romanian Adoptees study". Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines. 57 (10): 1113–1125. doi:10.1111/jcpp.12576. PMC 5042050. PMID 27264475.

- ^ Faraone SV, Biederman J (July 2016). "Can Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder Onset Occur in Adulthood?". JAMA Psychiatry. 73 (7): 655–656. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2016.0400. PMID 27191055.

- ^ Faraone SV, Banaschewski T, Coghill D, Zheng Y, Biederman J, Bellgrove MA, et al. (September 2021). "The World Federation of ADHD International Consensus Statement: 208 Evidence-based conclusions about the disorder". Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 128: 789–818. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2021.01.022. PMC 8328933. PMID 33549739.

- ^ a b CDC (6 January 2016). "Facts About ADHD". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Archived from the original on 22 March 2016. Retrieved 20 March 2016.

- ^ a b "Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder - National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH)". www.nimh.nih.gov. Retrieved 2 January 2024.

- ^ a b "Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder in Adults: What You Need to Know - National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH)". www.nimh.nih.gov. Retrieved 2 January 2024.

- ^ Dobie C (2012). "Diagnosis and management of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in primary care for school-age children and adolescents". p. 79. Archived from the original on 1 March 2013. Retrieved 10 October 2012.

- ^ a b Ramsay JR (2007). Cognitive behavioral therapy for adult ADHD. Routledge. pp. 4, 25–26. ISBN 978-0-415-95501-0.

- ^ Epstein JN, Loren RE (October 2013). "Changes in the Definition of ADHD in DSM-5: Subtle but Important". Neuropsychiatry. 3 (5): 455–458. doi:10.2217/npy.13.59. PMC 3955126. PMID 24644516.

- ^ Gershon J (January 2002). "A meta-analytic review of gender differences in ADHD". Journal of Attention Disorders. 5 (3): 143–154. doi:10.1177/108705470200500302. PMID 11911007. S2CID 8076914.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Kooij SJ, Bejerot S, Blackwell A, Caci H, Casas-Brugué M, Carpentier PJ, et al. (September 2010). "European consensus statement on diagnosis and treatment of adult ADHD: The European Network Adult ADHD". BMC Psychiatry. 10 (67): 67. doi:10.1186/1471-244X-10-67. PMC 2942810. PMID 20815868.

- ^ Carpenter Rich E, Loo SK, Yang M, Dang J, Smalley SL (July 2009). "Social functioning difficulties in ADHD: association with PDD risk". Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 14 (3): 329–344. doi:10.1177/1359104508100890. PMC 2827258. PMID 19515751.

- ^ Coleman WL (August 2008). "Social competence and friendship formation in adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder". Adolescent Medicine. 19 (2): 278–99, x. PMID 18822833.

- ^ "ADHD Anger Management Directory". Webmd.com. Archived from the original on 5 November 2013. Retrieved 17 January 2014.

- ^ a b c "F90 Hyperkinetic disorders". International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems 10th Revision. World Health Organisation. 2010. Archived from the original on 2 November 2014. Retrieved 2 November 2014.

- ^ Bellani M, Moretti A, Perlini C, Brambilla P (December 2011). "Language disturbances in ADHD". Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences. 20 (4): 311–315. doi:10.1017/S2045796011000527. PMID 22201208.

- ^ Racine MB, Majnemer A, Shevell M, Snider L (April 2008). "Handwriting performance in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)". Journal of Child Neurology. 23 (4): 399–406. doi:10.1177/0883073807309244. PMID 18401033. S2CID 206546871.

- ^ Peterson RL, Pennington BF (May 2012). "Developmental dyslexia". Lancet. 379 (9830): 1997–2007. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60198-6. PMC 3465717. PMID 22513218.

- ^ Sexton CC, Gelhorn HL, Bell JA, Classi PM (November 2012). "The co-occurrence of reading disorder and ADHD: epidemiology, treatment, psychosocial impact, and economic burden". Journal of Learning Disabilities. 45 (6): 538–564. doi:10.1177/0022219411407772. PMID 21757683. S2CID 385238.

- ^ Nicolson RI, Fawcett AJ (January 2011). "Dyslexia, dysgraphia, procedural learning and the cerebellum". Cortex; A Journal Devoted to the Study of the Nervous System and Behavior. 47 (1): 117–127. doi:10.1016/j.cortex.2009.08.016. PMID 19818437. S2CID 32228208.

- ^ "Dyslexia and ADHD". Archived from the original on 21 February 2023. Retrieved 19 May 2022.

- ^ a b Walitza S, Drechsler R, Ball J (August 2012). "[The school child with ADHD]" [The school child with ADHD]. Therapeutische Umschau. Revue Therapeutique (in German). 69 (8): 467–473. doi:10.1024/0040-5930/a000316. PMID 22851461.

- ^ Young S, Hollingdale J, Absoud M, Bolton P, Branney P, Colley W, et al. (May 2020). "Guidance for identification and treatment of individuals with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder and autism spectrum disorder based upon expert consensus". BMC Medicine. 18 (1). Springer Science and Business Media LLC: 146. doi:10.1186/s12916-020-01585-y. PMC 7247165. PMID 32448170.

- ^ a b c "ADHD Symptoms". nhs.uk. 20 October 2017. Archived from the original on 1 February 2021. Retrieved 15 May 2018.

- ^ a b Bailey E (5 September 2007). "ADHD and Learning Disabilities: How can you help your child cope with ADHD and subsequent Learning Difficulties? There is a way". Remedy Health Media, LLC. Archived from the original on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 15 November 2013.

- ^ Krull KR (5 December 2007). "Evaluation and diagnosis of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in children". Uptodate. Wolters Kluwer Health. Archived from the original on 5 June 2009. Retrieved 12 September 2008.

- ^ Hofvander B, Ossowski D, Lundström S, Anckarsäter H (2009). "Continuity of aggressive antisocial behavior from childhood to adulthood: The question of phenotype definition". International Journal of Law and Psychiatry. 32 (4): 224–234. doi:10.1016/j.ijlp.2009.04.004. PMID 19428109. Archived from the original on 17 May 2022. Retrieved 22 November 2021.

- ^ Rubia K (June 2011). ""Cool" inferior frontostriatal dysfunction in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder versus "hot" ventromedial orbitofrontal-limbic dysfunction in conduct disorder: a review". Biological Psychiatry. 69 (12). Elsevier BV/The Society of Biological Psychiatry: e69–e87. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.09.023. PMID 21094938. S2CID 14987165.

- ^ a b Wilens TE, Spencer TJ (September 2010). "Understanding attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder from childhood to adulthood". Postgraduate Medicine. 122 (5): 97–109. doi:10.3810/pgm.2010.09.2206. PMC 3724232. PMID 20861593.

- ^ Baud P, Perroud N, Aubry JM (June 2011). "[Bipolar disorder and attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder in adults: differential diagnosis or comorbidity]". Revue Medicale Suisse (in French). 7 (297): 1219–1222. doi:10.53738/REVMED.2011.7.297.1219. PMID 21717696.

- ^ Wilens TE, Morrison NR (July 2011). "The intersection of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and substance abuse". Current Opinion in Psychiatry. 24 (4): 280–285. doi:10.1097/YCO.0b013e328345c956. PMC 3435098. PMID 21483267.

- ^ Corkum P, Davidson F, Macpherson M (June 2011). "A framework for the assessment and treatment of sleep problems in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder". Pediatric Clinics of North America. 58 (3): 667–683. doi:10.1016/j.pcl.2011.03.004. PMID 21600348.

- ^ Tsai MH, Huang YS (May 2010). "Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and sleep disorders in children". The Medical Clinics of North America. 94 (3): 615–632. doi:10.1016/j.mcna.2010.03.008. PMID 20451036.

- ^ Bendz LM, Scates AC (January 2010). "Melatonin treatment for insomnia in pediatric patients with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder". The Annals of Pharmacotherapy. 44 (1): 185–191. doi:10.1345/aph.1M365. PMID 20028959. S2CID 207263711.

- ^ Merino-Andreu M (March 2011). "[Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and restless legs syndrome in children]" [Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and restless legs syndrome in children]. Revista de Neurologia (in Spanish). 52 (Suppl 1): S85–S95. doi:10.33588/rn.52S01.2011037. PMID 21365608.

- ^ Picchietti MA, Picchietti DL (August 2010). "Advances in pediatric restless legs syndrome: Iron, genetics, diagnosis and treatment". Sleep Medicine. 11 (7): 643–651. doi:10.1016/j.sleep.2009.11.014. PMID 20620105.

- ^ Karroum E, Konofal E, Arnulf I (2008). "[Restless-legs syndrome]". Revue Neurologique (in French). 164 (8–9): 701–721. doi:10.1016/j.neurol.2008.06.006. PMID 18656214.

- ^ Wajszilber D, Santiseban JA, Gruber R (December 2018). "Sleep disorders in patients with ADHD: impact and management challenges". Nature and Science of Sleep. 10: 453–480. doi:10.2147/NSS.S163074. PMC 6299464. PMID 30588139.

- ^ Long Y, Pan N, Ji S, Qin K, Chen Y, Zhang X, et al. (September 2022). "Distinct brain structural abnormalities in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and substance use disorders: A comparative meta-analysis". Translational Psychiatry. 12 (1): 368. doi:10.1038/s41398-022-02130-6. PMC 9448791. PMID 36068207.

- ^ a b c National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health (2009). "Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder". Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder: Diagnosis and Management of ADHD in Children, Young People and Adults. NICE Clinical Guidelines. Vol. 72. Leicester: British Psychological Society. pp. 18–26, 38. ISBN 978-1-85433-471-8. Archived from the original on 13 January 2016 – via NCBI Bookshelf.

- ^ Storebø OJ, Rasmussen PD, Simonsen E (February 2016). "Association Between Insecure Attachment and ADHD: Environmental Mediating Factors" (PDF). Journal of Attention Disorders. 20 (2): 187–196. doi:10.1177/1087054713501079. PMID 24062279. S2CID 23564305. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 December 2021. Retrieved 22 November 2021.

- ^ Becker SP, Willcutt EG, Leopold DR, Fredrick JW, Smith ZR, Jacobson LA, et al. (June 2023). "Report of a Work Group on Sluggish Cognitive Tempo: Key Research Directions and a Consensus Change in Terminology to Cognitive Disengagement Syndrome". Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 62 (6): 629–645. doi:10.1016/j.jaac.2022.07.821. PMC 9943858. PMID 36007816.

- ^ Barkley RA (January 2014). "Sluggish cognitive tempo (concentration deficit disorder?): current status, future directions, and a plea to change the name" (PDF). Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 42 (1): 117–125. doi:10.1007/s10802-013-9824-y. PMID 24234590. S2CID 8287560. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 August 2017.

- ^ Nazar BP, Bernardes C, Peachey G, Sergeant J, Mattos P, Treasure J (December 2016). "The risk of eating disorders comorbid with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis". The International Journal of Eating Disorders. 49 (12): 1045–1057. doi:10.1002/eat.22643. PMID 27859581. S2CID 38002526. Archived from the original on 8 December 2022. Retrieved 26 October 2022.

- ^ Schneider M, VanOrmer J, Zlomke K (2019). "Adverse Childhood Experiences and Family Resilience Among Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder and Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder". Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics. 40 (8): 573–580. doi:10.1097/DBP.0000000000000703. PMID 31335581. S2CID 198193637.

- ^ Moon DS, Bong SJ, Kim BN, Kang NR (January 2021). "Association between Maternal Adverse Childhood Experiences and Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder in the Offspring: The Mediating Role of Antepartum Health Risks". Soa--Ch'ongsonyon Chongsin Uihak = Journal of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 32 (1): 28–34. doi:10.5765/jkacap.200041. PMC 7788667. PMID 33424239.

- ^ Ford JD, Connor DF (1 June 2009). "ADHD and post-traumatic stress disorder". Current Attention Disorders Reports. 1 (2): 60–66. doi:10.1007/s12618-009-0009-0. ISSN 1943-457X. S2CID 145508751.

- ^ Harrington KM, Miller MW, Wolf EJ, Reardon AF, Ryabchenko KA, Ofrat S (August 2012). "Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder comorbidity in a sample of veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder". Comprehensive Psychiatry. 53 (6): 679–690. doi:10.1016/j.comppsych.2011.12.001. PMC 6519447. PMID 22305866.

- ^ a b Szymanski K, Sapanski L, Conway F (1 January 2011). "Trauma and ADHD – Association or Diagnostic Confusion? A Clinical Perspective". Journal of Infant, Child, and Adolescent Psychotherapy. 10 (1). Philadelphia PA: Taylor & Francis Group: 51–59. doi:10.1080/15289168.2011.575704. eISSN 1940-9214. ISSN 1528-9168. S2CID 144348893.

- ^ Zhang N, Gao M, Yu J, Zhang Q, Wang W, Zhou C, et al. (October 2022). "Understanding the association between adverse childhood experiences and subsequent attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies". Brain and Behavior. 12 (10): e32748. doi:10.1002/brb3.2748. PMC 9575611. PMID 36068993.

- ^ Nguyen MN, Watanabe-Galloway S, Hill JL, Siahpush M, Tibbits MK, Wichman C (June 2019). "Ecological model of school engagement and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in school-aged children". European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 28 (6): 795–805. doi:10.1007/s00787-018-1248-3. PMID 30390147. S2CID 53263217.

- ^ Miodus S, Allwood MA, Amoh N (5 January 2021). "Childhood ADHD Symptoms in Relation to Trauma Exposure and PTSD Symptoms Among College Students: Attending to and Accommodating Trauma". Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders. 29 (3): 187–196. doi:10.1177/1063426620982624. ISSN 1063-4266. S2CID 234159064.

- ^ Williams AE, Giust JM, Kronenberger WG, Dunn DW (2016). "Epilepsy and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: links, risks, and challenges". Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment. 12: 287–296. doi:10.2147/NDT.S81549. PMC 4755462. PMID 26929624.

- ^ Silva RR, Munoz DM, Alpert M (March 1996). "Carbamazepine use in children and adolescents with features of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: a meta-analysis". Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 35 (3): 352–358. doi:10.1097/00004583-199603000-00017. PMID 8714324.

- ^ Instanes JT, Klungsøyr K, Halmøy A, Fasmer OB, Haavik J (February 2018). "Adult ADHD and Comorbid Somatic Disease: A Systematic Literature Review". Journal of Attention Disorders (Systematic Review). 22 (3): 203–228. doi:10.1177/1087054716669589. PMC 5987989. PMID 27664125.

- ^ Gaur S (May 2022). "The Association between ADHD and Celiac Disease in Children". Children. 9 (6). MDPI: 781. doi:10.3390/children9060781. PMC 9221618. PMID 35740718.

- ^ Hsu TW, Chen MH, Chu CS, Tsai SJ, Bai YM, Su TP, et al. (May 2022). "Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and risk of migraine: A nationwide longitudinal study". Headache. 62 (5): 634–641. doi:10.1111/head.14306. PMID 35524451. S2CID 248553863.

- ^ Salem H, Vivas D, Cao F, Kazimi IF, Teixeira AL, Zeni CP (March 2018). "ADHD is associated with migraine: a systematic review and meta-analysis". European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 27 (3). Springer Science and Business Media LLC: 267–277. doi:10.1007/s00787-017-1045-4. PMID 28905127. S2CID 3949012.

- ^ Pan PY, Jonsson U, Şahpazoğlu Çakmak SS, Häge A, Hohmann S, Nobel Norrman H, et al. (January 2022). "Headache in ADHD as comorbidity and a side effect of medications: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Psychological Medicine. 52 (1). Cambridge University Press: 14–25. doi:10.1017/s0033291721004141. PMC 8711104. PMID 34635194.

- ^ Cannon Homaei S, Barone H, Kleppe R, Betari N, Reif A, Haavik J (January 2022). "ADHD symptoms in neurometabolic diseases: Underlying mechanisms and clinical implications". Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 132: 838–856. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2021.11.012. PMID 34774900. S2CID 243983688.

- ^ Brunkhorst-Kanaan N, Libutzki B, Reif A, Larsson H, McNeill RV, Kittel-Schneider S (June 2021). "ADHD and accidents over the life span - A systematic review". Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 125. Elsevier: 582–591. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2021.02.002. PMID 33582234. S2CID 231885131.

- ^ Vaa T (January 2014). "ADHD and relative risk of accidents in road traffic: a meta-analysis". Accident; Analysis and Prevention. 62. Elsevier: 415–425. doi:10.1016/j.aap.2013.10.003. hdl:11250/2603537. PMID 24238842.

- ^ "Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)". nhs.uk. 1 June 2018. Retrieved 16 February 2024.

- ^ González-Bueso V, Santamaría JJ, Fernández D, Merino L, Montero E, Ribas J (2018). "Association between Internet Gaming Disorder or Pathological Video-Game Use and Comorbid Psychopathology: A Comprehensive Review". International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 15 (4). MDPI: 668. doi:10.3390/ijerph15040668. PMC 5923710. PMID 29614059.

- ^ Beyens I, Valkenburg PM, Piotrowski JT (2 October 2018). "Screen media use and ADHD-related behaviors: Four decades of research". PNAS USA. 115 (40). National Academy of Sciences: 9875–9881. Bibcode:2018PNAS..115.9875B. doi:10.1073/pnas.1611611114. PMC 6176582. PMID 30275318.

- ^ de Francisco Carvalho L, Sette CP, Ferrari BL (2018). "Problematic smartphone use relationship with pathological personality traits: Systematic review and meta-analysis". Cyberpsychology: Journal of Psychosocial Research on Cyberspace. 12 (3). Masaryk University: 5. doi:10.5817/CP2018-3-5.

- ^ Li Y, Li G, Liu L, Wu H (2020). "Correlations between mobile phone addiction and anxiety, depression, impulsivity, and poor sleep quality among college students: A systematic review and meta-analysis". Journal of Behavioral Addictions. 9 (3). Akadémiai Kiadó: 551–571. doi:10.1556/2006.2020.00057. PMC 8943681. PMID 32903205.

- ^ Dullur P, Krishnan V, Diaz AM (2021). "A systematic review on the intersection of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder and gaming disorder". Journal of Psychiatric Research. 133. Elsevier: 212–222. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2020.12.026. PMID 33360866. S2CID 229687229.

- ^ Gao X, Zhang M, Yang Z, Wen M, Huang H, Zheng R, et al. (2021). "Structural and Functional Brain Abnormalities in Internet Gaming Disorder and Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder: A Comparative Meta-Analysis". Frontiers in Psychiatry. 12. Frontiers Media: 679437. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2021.679437. PMC 8281314. PMID 34276447.

- ^ Eirich R, McArthur BA, Anhorn C, McGuinness C, Christakis DA, Madigan S (2022). "Association of Screen Time With Internalizing and Externalizing Behavior Problems in Children 12 Years or Younger: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis". JAMA Psychiatry. 79 (5). American Medical Association: 393–405. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2022.0155. PMC 8928099. PMID 35293954.

- ^ Santos RM, Mendes CG, Miranda DM, Romano-Silva MA (2022). "The Association between Screen Time and Attention in Children: A Systematic Review". Developmental Neuropsychology. 47 (4). Routledge: 175–192. doi:10.1080/87565641.2022.2064863. PMID 35430923. S2CID 248228233.

- ^ Werling AM, Kuzhippallil S, Emery S, Walitza S, Drechsler R (2022). "Problematic use of digital media in children and adolescents with a diagnosis of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder compared to controls. A meta-analysis". Journal of Behavioral Addictions. 11 (2). Akadémiai Kiadó: 305–325. doi:10.1556/2006.2022.00007. PMC 9295226. PMID 35567763.

- ^ Thorell LB, Burén J, Wiman JS, Sandberg D, Nutley SB (2022). "Longitudinal associations between digital media use and ADHD symptoms in children and adolescents: a systematic literature review". European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. Springer Science+Business Media. doi:10.1007/s00787-022-02130-3. PMID 36562860.

- ^ Liu H, Chen X, Huang M, Yu X, Gan Y, Wang J, et al. (2023). "Screen time and childhood attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a meta-analysis". Reviews on Environmental Health. De Gruyter. doi:10.1515/reveh-2022-0262. PMID 37163581. S2CID 258591184.

- ^ Augner C, Vlasak T, Barth A (2023). "The relationship between problematic internet use and attention deficit, hyperactivity and impulsivity: A meta-analysis". Journal of Psychiatric Research. 168. Elsevier: 1–12. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2023.10.032. PMID 37866293. S2CID 264190691.

- ^ Koncz P, Demetrovics Z, Takacs ZK, Griffiths MD, Nagy T, Király O (2023). "The emerging evidence on the association between symptoms of ADHD and gaming disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis". Clinical Psychology Review. 106. Elsevier: 102343. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2023.102343. PMID 37883910.

- ^ Balazs J, Kereszteny A (March 2017). "Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and suicide: A systematic review". World Journal of Psychiatry. 7 (1): 44–59. doi:10.5498/wjp.v7.i1.44. PMC 5371172. PMID 28401048.

- ^ a b Garas P, Balazs J (21 December 2020). "Long-Term Suicide Risk of Children and Adolescents With Attention Deficit and Hyperactivity Disorder-A Systematic Review". Frontiers in Psychiatry. 11: 557909. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2020.557909. PMC 7779592. PMID 33408650. 557909.

- ^ a b Septier M, Stordeur C, Zhang J, Delorme R, Cortese S (August 2019). "Association between suicidal spectrum behaviors and Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis". Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 103: 109–118. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2019.05.022. PMID 31129238. S2CID 162184004. Archived from the original on 4 November 2021. Retrieved 7 December 2021.

- ^ Beauchaine TP, Ben-David I, Bos M (September 2020). "ADHD, financial distress, and suicide in adulthood: A population study". Science Advances. 6 (40): eaba1551. Bibcode:2020SciA....6.1551B. doi:10.1126/sciadv.aba1551. PMC 7527218. PMID 32998893. eaba1551.

- ^ Frazier TW, Demaree HA, Youngstrom EA (July 2004). "Meta-analysis of intellectual and neuropsychological test performance in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder". Neuropsychology. 18 (3): 543–555. doi:10.1037/0894-4105.18.3.543. PMID 15291732. S2CID 17628705.

- ^ Mackenzie GB, Wonders E (2016). "Rethinking Intelligence Quotient Exclusion Criteria Practices in the Study of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder". Frontiers in Psychology. 7: 794. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00794. PMC 4886698. PMID 27303350.

- ^ Rommelse N, van der Kruijs M, Damhuis J, Hoek I, Smeets S, Antshel KM, et al. (December 2016). "An evidenced-based perspective on the validity of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in the context of high intelligence". Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 71: 21–47. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.08.032. hdl:2066/163023. PMID 27590827. S2CID 6698847.

- ^ Bridgett DJ, Walker ME (March 2006). "Intellectual functioning in adults with ADHD: a meta-analytic examination of full scale IQ differences between adults with and without ADHD". Psychological Assessment. 18 (1): 1–14. doi:10.1037/1040-3590.18.1.1. PMID 16594807.

- ^ a b c d e Faraone SV, Banaschewski T, Coghill D, Zheng Y, Biederman J, Bellgrove MA, et al. (September 2021). "The World Federation of ADHD International Consensus Statement: 208 Evidence-based conclusions about the disorder". Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 128: 789–818. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2021.01.022. hdl:2318/1791803. PMC 8328933. PMID 33549739.

- ^ Biederman J (June 2005). "Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a selective overview". Biological Psychiatry. 57 (11): 1215–1220. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.10.020. PMID 15949990. S2CID 23671547.

- ^ Faraone SV, Larsson H (April 2019). "Genetics of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder". Molecular Psychiatry. 24 (4): 562–575. doi:10.1038/s41380-018-0070-0. PMC 6477889. PMID 29892054. S2CID 47016805.

- ^ "APA PsycNet". psycnet.apa.org. Retrieved 12 January 2024.

- ^ Demontis D, Walters RK, Martin J, Mattheisen M, Als TD, Agerbo E, et al. (January 2019). "Discovery of the first genome-wide significant risk loci for attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder". Nature Genetics. 51 (1): 63–75. doi:10.1038/s41588-018-0269-7. hdl:10023/20827. PMC 6481311. PMID 30478444.

- ^ "Intergenerational transmission of ADHD behaviors: More evidence for heritability than life history theor". europepmc.org. 2022. Retrieved 12 January 2024.

- ^ a b c d Grimm O, Kranz TM, Reif A (February 2020). "Genetics of ADHD: What Should the Clinician Know?". Current Psychiatry Reports. 22 (4): 18. doi:10.1007/s11920-020-1141-x. PMC 7046577. PMID 32108282.

- ^ Larsson H, Chang Z, D'Onofrio BM, Lichtenstein P (July 2014). "The heritability of clinically diagnosed attention deficit hyperactivity disorder across the lifespan". Psychological Medicine. 44 (10): 2223–2229. doi:10.1017/S0033291713002493. hdl:10616/41709. PMC 4071160. PMID 24107258.

- ^ [131][132][133][134][135][136]

- ^ Cederlöf M, Ohlsson Gotby A, Larsson H, Serlachius E, Boman M, Långström N, et al. (January 2014). "Klinefelter syndrome and risk of psychosis, autism and ADHD". Journal of Psychiatric Research. 48 (1): 128–130. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2013.10.001. PMID 24139812.

- ^ Biederman J, Spencer T (November 1999). "Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) as a noradrenergic disorder". Biological Psychiatry. 46 (9). Elsevier: 1234–1242. doi:10.1016/S0006-3223(99)00192-4. PMID 10560028. S2CID 45497168.

- ^ Faraone SV, Larsson H (April 2019). "Genetics of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder". Molecular Psychiatry. 24 (4). Nature Research: 562–575. doi:10.1038/s41380-018-0070-0. PMC 6477889. PMID 29892054.

- ^ Baron-Cohen S (June 2002). "The extreme male brain theory of autism". Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 6 (6). Elsevier: 248–254. doi:10.1016/S1364-6613(02)01904-6. PMID 12039606. S2CID 8098723. Archived from the original on 3 July 2013. Retrieved 9 July 2020.

- ^ Nesse RM (2005). "32. Evolutionary Psychology and Mental Health". In Buss DM (ed.). The Handbook of Evolutionary Psychology (1st ed.). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley. p. 918. ISBN 978-0-471-26403-3.

- ^ Nesse RM (2016) [2005]. "43. Evolutionary Psychology and Mental Health". In Buss DM (ed.). The Handbook of Evolutionary Psychology, Volume 2: Integrations (2nd ed.). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley. p. 1019. ISBN 978-1-118-75580-8.

- ^ Esteller-Cucala P, Maceda I, Børglum AD, Demontis D, Faraone SV, Cormand B, et al. (May 2020). "Genomic analysis of the natural history of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder using Neanderthal and ancient Homo sapiens samples". Scientific Reports. 10 (1): 8622. Bibcode:2020NatSR..10.8622E. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-65322-4. PMC 7248073. PMID 32451437.

- ^ "APA PsycNet". psycnet.apa.org. Retrieved 5 March 2024.

- ^ "APA PsycNet". psycnet.apa.org. Retrieved 28 March 2024.

- ^ Faraone SV, Larsson H (April 2019). "Genetics of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder". Molecular Psychiatry. 24 (4). Springer Science and Business Media LLC: 562–575. doi:10.1038/s41380-018-0070-0. PMC 6477889. PMID 29892054.

- ^ Nolen-Hoeksema S (2013). Abnormal Psychology (6th ed.). McGraw-Hill Education. p. 267. ISBN 978-0-07-803538-8.

- ^ Skoglund C, Chen Q, D'Onofrio BM, Lichtenstein P, Larsson H (January 2014). "Familial confounding of the association between maternal smoking during pregnancy and ADHD in offspring". Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines. 55 (1): 61–68. doi:10.1111/jcpp.12124. PMC 4217138. PMID 25359172.

- ^ Obel C, Zhu JL, Olsen J, Breining S, Li J, Grønborg TK, et al. (April 2016). "The risk of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in children exposed to maternal smoking during pregnancy - a re-examination using a sibling design". Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines. 57 (4): 532–537. doi:10.1111/jcpp.12478. PMID 26511313.

- ^ Biederman J (June 2005). "Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a selective overview". Biological Psychiatry. 57 (11): 1215–1220. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.10.020. PMID 15949990.

- ^ Hinshaw SP (May 2018). "Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD): Controversy, Developmental Mechanisms, and Multiple Levels of Analysis". Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 14 (1): 291–316. doi:10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-050817-084917. PMID 29220204.

- ^ Kebir O, Joober R (December 2011). "Neuropsychological endophenotypes in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a review of genetic association studies". European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience. 261 (8): 583–594. doi:10.1007/s00406-011-0207-5. PMID 21409419. S2CID 21383749.

- ^ a b Berry MD (January 2007). "The potential of trace amines and their receptors for treating neurological and psychiatric diseases". Reviews on Recent Clinical Trials. 2 (1): 3–19. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.329.563. doi:10.2174/157488707779318107. PMID 18473983.

Although there is little direct evidence, changes in trace amines, in particular PE, have been identified as a possible factor for the onset of attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). ... Further, amphetamines, which have clinical utility in ADHD, are good ligands at trace amine receptors. Of possible relevance in this aspect is modafanil, which has shown beneficial effects in ADHD patients and has been reported to enhance the activity of PE at TAAR1. Conversely, methylphenidate, ...showed poor efficacy at the TAAR1 receptor. In this respect it is worth noting that the enhancement of functioning at TAAR1 seen with modafanil was not a result of a direct interaction with TAAR1.

- ^ Sotnikova TD, Caron MG, Gainetdinov RR (August 2009). "Trace amine-associated receptors as emerging therapeutic targets". Molecular Pharmacology. 76 (2): 229–235. doi:10.1124/mol.109.055970. PMC 2713119. PMID 19389919.

- ^ Gizer IR, Ficks C, Waldman ID (July 2009). "Candidate gene studies of ADHD: a meta-analytic review". Human Genetics. 126 (1): 51–90. doi:10.1007/s00439-009-0694-x. PMID 19506906. S2CID 166017.