도파민 운반체

Dopamine transporter| SLC6A3 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 식별자 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 별칭 | SLC6A3, 솔루트 운반체 패밀리 6(뉴로트랜스포터), 멤버 3, DAT, DAT1, PKDYS, 솔루트 운반체 패밀리 6 멤버 3, 도파민 트랜스포터, PKDYS1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 외부 ID | OMIM: 126455 MGI: 94862 HomoloGene: 55547 GeneCard: SLC6A3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 직교체 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 종 | 인간 | 마우스 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| 엔트레스 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 앙상블 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 유니프로트 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| RefSeq(mRNA) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| RefSeq(단백질) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 위치(UCSC) | Cr 5: 1.39 – 1.45Mb | Cr 13: 73.54 – 73.58Mb | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| PubMed 검색 | [3] | [4] | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| 위키다타 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

도파민 트랜스포터(도파민 활성 트랜스포터, DAT, SLC6A3)는 시냅스 구획에서 신경전달물질 도파민을 다시 시토솔로 펌프하는 막경간 단백질이다. 시토솔에서는 다른 운반자들이 도파민을 염소에 격리시켜 보관하고 나중에 방출한다. DAT를 통한 도파민 재흡수는 도파민이 시냅스에서 제거되는 1차 메커니즘을 제공한다. 단, 증거가 노레피네프린 트랜스포터의 더 큰 역할을 가리킬 수 있는 전두엽 피질에는 예외가 있을 수 있다.[5]

DAT는 주의력결핍 과잉행동장애, 조울증, 임상우울증, 알코올중독, 섭식장애, 약물사용장애 등 도파민 관련 질환에 다수 연루돼 있다. DAT 단백질을 인코딩하는 유전자는 인간 5번 염색체에 위치하며, 15개의 코딩 엑손(coding exon)으로 구성되며, 길이는 약 64kbp이다. DAT와 도파민 관련 장애의 연관성에 대한 증거는 표현된 단백질의 양에 영향을 미치는 DAT 유전자(DAT1)에서 VNTR로 알려진 유전적 다형성 유형에서 나왔다.[6]

함수

DAT는 시냅스 구획에서 도파민을 제거해 주변 세포에 침전시켜 신경전달물질의 신호를 차단하는 일체형 막단 단백질이다. 도파민은 보상을 포함한 인식의 몇 가지 측면에 기초하며, DAT는 그 신호의 조절을 용이하게 한다.[7]

메커니즘

DAT는 나트륨 이온이 고농도에서 저농도로 이동하는 정력적으로 좋아하는 운동과 결합해 세포막을 가로질러 도파민을 움직이는 심포터다. DAT 기능에는 도파민 기질을 가진 두 Na+ 이온과 한 Cl− 이온의 순차 결합과 동시 전달이 필요하다. DAT 매개 도파민 재흡수 추진력은 플라즈마 막 Na+/K+ ATPase에 의해 발생하는 이온 농도 구배다.[8]

모노아민 전달 기능에 대해 가장 널리 받아들여지는 모델에서는 나트륨 이온이 도파민이 결합하기 전에 먼저 전달체의 세포외 영역에 결합해야 한다. 도파민이 결합되면 단백질은 순응적인 변화를 겪게 되는데, 이것은 나트륨과 도파민 둘 다 세포 내 피막에서 결합을 풀 수 있게 한다.[9]

전기생리학과 방사능 라벨 도파민을 이용한 연구에서는 신경전달물질 1개 분자를 1~2개의 나트륨 이온으로 막을 가로질러 운반할 수 있다는 점에서 도파민 전달체가 다른 모노아민 전달체와 유사하다는 사실을 확인했다. 염화 이온도 양전하의 축적을 막기 위해 필요하다. 이러한 연구들은 또한 운송 속도와 방향이 나트륨 경사로에 전적으로 의존한다는 것을 보여주었다.[10]

멤브레인 전위와 나트륨 경사의 긴밀한 결합으로 인해 활동으로 인한 멤브레인 극성의 변화는 전송 속도에 극적으로 영향을 미칠 수 있다. 게다가, 트랜스포터는 뉴런이 탈분극화되었을 때 도파민 방출을 유발할 수 있다.[10]

DAT-Cav 커플링

도파민 전달체가 사실상 모든 도파민 뉴런에 표현되는 L형 전압 게이트 칼슘 통로(특히 Ca1v.2와 Ca1v.3)에 결합한다는 예비 증거가 제시된다.[11] DAT-Cav 커플링의 결과, 트랜스포터를 통해 탈극화 전류를 생성하는 DAT 기판은 트랜스포터에 결합되는 칼슘 채널을 열 수 있어 도파민 뉴런의 칼슘 유입이 가능하다.[11] 이러한 칼슘 유입은 도파민 트랜스포터의 다운스트림 효과로서 CAMKII 매개 인산화를 유도하는 것으로 생각된다.[11] CAMK에 의한 DAT 인산염 때문이다.II 결과 도파민 체내 유출, 전달체 결합 칼슘 채널의 활성화는 특정 약물(예: 암페타민)이 신경전달물질을 방출하는 잠재적 메커니즘이다.[11]

단백질 구조

DAT의 멤브레인 위상의 초기 결정은 소수성 시퀀스 분석과 GABA 트랜스포터와의 시퀀스 유사성에 기초하였다. 이러한 방법들은 이 단백질 작은 조각으로 단백질을 소화시키 proteases과 세포 밖의 루프에서만으며 대체로 세포막의 초기 예측이 진실임을 입증했다 발생하면 포도당화, 언어를 사용하여 3,4TMDs.[12] 느려특성화 사이에 큰 세포외 루프에 열두 가닥의 투과 성막 도메인(TMD)으로 전망했다.로pology.[13] 드로소필라 멜라노가스터 도파민 트랜스포터(dDAT)의 정확한 구조는 2013년 X선 결정학에 의해 규명되었다.[14]

위치 및 분포

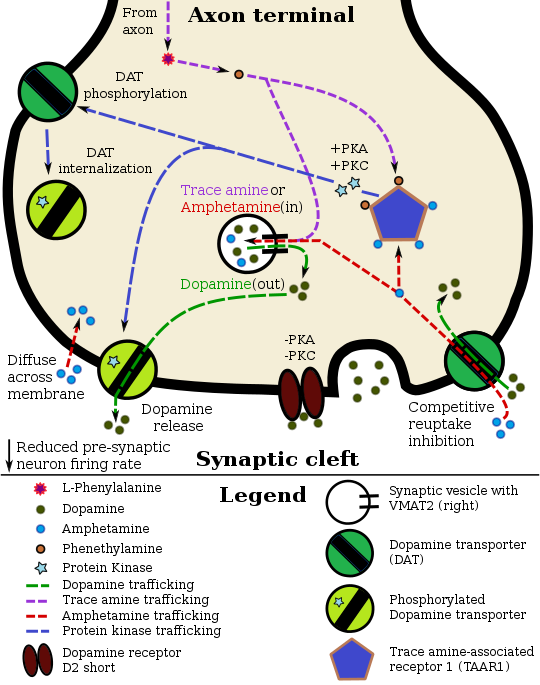

도파민 뉴런의 암페타민 약리역학 |

DAT의 국부 분포는 니그로스트라이탈, 중간임브릭 및 중간고사 경로를 포함한 도파민성 회로가 확립된 뇌의 영역에서 발견되었다.[22] 이러한 경로를 구성하는 핵은 뚜렷한 표현 패턴을 가지고 있다. 성체 생쥐의 유전자 발현 패턴은 실체형 니그라파스 콤팩타에서 높은 발현을 보여준다.[23]

방사성 항체로 라벨이 부착된 중간고사 경로의 DAT는 실체형 니그라파스 콤팩트 및 복측 테그먼트 영역의 뉴런의 덴드라이트 및 세포체에서 농축된 것으로 확인되었다. 이 패턴은 시냅스의 도파민 수치를 조절하는 단백질에 이치에 맞는다.

중간중간 경로의 선조체 및 핵에 점착하는 것은 밀도가 높고 이질적이었다. 선조체에서 DAT는 액손 단자의 플라즈마 막에 국부화되어 있다. 이중 면역세포화학은 니그로스트라이탈 단자의 다른 두 표식인 티로신 수산화효소와 D2 도파민 수용체를 통해 DAT 콜로칼화 현상을 입증했다. 따라서 후자는 도파민을 방출하는 세포의 자동수용체임이 입증되었다. TAAR1은 DAT와 함께 콜로컬레이션되어 활성화되었을 때 D2 자동수용기와 반대되는 효과가 있는 사전 시냅스 세포내 수용체로서 PKA와 PKC신호를 통해 도파민 전달체를 내장하고 역전달 기능을 통해 배출을 유도한다.[15][24]

놀랍게도, 어떤 시냅스 활동 영역에서도 DAT가 식별되지 않았다. 이러한 결과는 일단 도파민이 시냅스 구획으로부터 확산되면 선조체 도파민 재흡수가 시냅스 전문화 밖에서 발생할 수 있음을 시사한다.

실체형 니그라에서 DAT는 축 및 덴드리트(즉, 사전 및 사후 시냅틱) 플라즈마 막으로 국부화된다.[25]

파스 콤팩트카 뉴런의 perikarya 내에서 DAT는 주로 거칠고 매끄러운 내소성 망막, 골지 콤플렉스, 다발성 몸체에 국부화되어 합성, 수정, 이송 및 분해의 가능한 부위를 식별하였다.[26]

유전학 및 규제

DAT1로 알려진 DAT의 유전자는 5p15 염색체에 위치한다.[6] 유전자의 단백질 부호화 부위는 64kb 이상이며 15개의 부호화 세그먼트 또는 엑손으로 구성된다.[27] 이 유전자는 3의 끝(rs28363170)에 가변 수 탠덤 반복(VNTR)을 가지고 있으며, 인트론 8 영역에 다른 유전자가 있다.[28] VNTR의 차이는 전달체의 기저 발현 수준에 영향을 미치는 것으로 밝혀져 연구자들은 도파민 관련 질환과의 연관성을 찾아냈다.[29]

많은 도파민 관련 유전자를 조절하는 핵수용체 누르르1은 이 유전자의 촉진부위를 묶고 발현을 유도할 수 있다.[30] 또한 이 프로모터는 전사 인자 Sp-1의 대상이 될 수 있다.

전사 인자는 어떤 세포가 DAT를 표현하는지 조절하지만, 이 단백질의 기능적 조절은 키나제에 의해 주로 이루어진다. MAPK,[31] CAMKII,[20][21] PKA,[15] PKC는[21][32] 트랜스포터가 도파민을 이동시키거나 DAT의 내장을 일으키는 속도를 조절할 수 있다. 공동 국소화된 TAAR1은 활성화되었을 때 단백질 키나아제 A(PKA) 신호와 단백질 키나아제 C(PKC) 신호를 통해 DAT를 인지하는 도파민 전달체의 중요한 조절기다.[15][33] 단백질 키나아제 중 하나에 의한 인산염은 DAT 내화(비경쟁적 재흡수 억제)를 초래할 수 있지만 PKC 매개 인산염만으로도 역전달 기능(도파민 유출)을 유도한다.[15][34] 도파민 자동수용기도 TAAR1 활성화 효과를 직접 반대해 DAT를 조절한다.[15]

인간 도파민 트랜스포터(hDAT)는 아연 결합 시 도파민 재흡수를 억제하고 암페타민 유도 도파민 배출량을 체외에서 증폭시키는 고친화성 세포외 아연 결합 부지를 함유하고 있다.[35][36][37] 반면 인간 세로토닌 트랜스포터(hSERT)와 인간 노레피네프린 트랜스포터(hNET)는 아연 결합 부위가 들어 있지 않다.[37] 아연 보충제는 주의력 결핍 과잉행동장애 치료에 사용될 때 암페타민의 최소 유효량을 감소시킬 수 있다.[38]

생물학적 역할 및 장애

DAT가 시냅스에서 도파민을 제거하는 속도는 세포 내 도파민 양에 지대한 영향을 미칠 수 있다. 이는 도파민 전달체가 없는 생쥐의 심각한 인지결손, 운동 이상, 과잉행동 등이 이를 가장 잘 입증한다.[39] 이러한 특징들은 ADHD의 증상과 현저하게 유사하다.

기능 VNTR의 차이는 양극성 장애와[40] ADHD의 위험 요인으로 확인되었다.[41] 논란이 일지만 알코올 중독에서 탈퇴 증상이 더 강한 연관성도 있음을 시사하는 자료가 등장했다.[42][43] 정상 단백질 수치를 가진 DAT 유전자의 대립은 금연 행동과 금연의 용이성과 관련이 있다.[44] 또한 남성 청소년 특히 10알레 VNTR 반복을 수행하는 고위험군 가족(탈모 및 모성애 없는 가족으로 표시됨)의 경우 반사회적 또래에 대해 통계적으로 유의미한 친화력을 보인다.[45][46]

DAT의 활동 증가는 임상 우울증을 포함한 몇 가지 다른 장애와 관련이 있다.[47]

DAT의 돌연변이로 인해 도파민 트랜스포터 결핍 증후군이 발생하는 것으로 나타났는데, 도파민 열성 운동 장애는 디스토니아와 파킨슨병을 지속적으로 악화시키는 것이 특징이다.[48]

약리학

도파민 트랜스포터는 기질, 도파민 유착제, 운반억제제, 알로스테릭 변조기 등이 대상이다.[49][50]

코카인은 트랜스포터에 직접 결합하고 전송 속도를 줄여 DAT를 차단한다.[12] 이와는 대조적으로 암페타민은 뉴런막이나 DAT를 통해 직접 시냅스 전 뉴런에 들어가 도파민과 재흡수 경쟁을 벌인다. 일단 안으로 들어가면 를 통해 시냅스 vesicle에 결합하거나 들어간다. 암페타민이 TAAR1에 결합하면 시냅스 후 뉴런의 발화율을 낮추고 단백질 키나제 A와 단백질 키나제 C 신호를 유발해 DAT 인산화 효과가 발생한다. 인산염 DAT는 역방향으로 작동하거나 사전 시냅스 뉴런으로 철수하여 이송을 중단한다. 암페타민이 VMAT2를 통해 시냅스 vesicle에 들어가면 도파민이 시토솔로 방출된다.[15][16] 암페타민은 또한 수송기의 CAMKIIα 매개 인산화 작용과 관련된 두 번째 TAAR1 독립 메커니즘을 통해 도파민 방출을 생성하는데, 이것은 암페타민에 의한 DAT 결합 L형 칼슘 채널의 활성화에서 주로 발생한다.[11]

각 약물의 도파민성 메커니즘은 이러한 물질에 의해 도출된 즐거운 감정의 바탕이 된다고 여겨진다.[7]

상호작용

도파민 운반체는 다음 사항과 상호 작용하는 것으로 나타났다.

이러한 선천적인 단백질-단백질 상호작용과는 별개로, 최근의 연구는 HIV-1 Tat 단백질과 같은 바이러스성 단백질이 DAT와[55][56] 상호작용을 하며, 이러한 결합은 HIV 양성자의 도파민 동족수증을 변화시킬 수 있다는 것을 증명했는데, 이것은 HIV 관련 신경인지 장애의 원인이 되는 요인이다.[57]

참고 항목

참조

- ^ a b c ENSG00000276996 GRCh38: 앙상블 릴리스 89: ENSG00000142319, ENSG00000276996 - 앙상블, 2017년 5월

- ^ a b c GRCm38: 앙상블 릴리스 89: ENSMUSG000021609 - 앙상블, 2017년 5월

- ^ "Human PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ "Mouse PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ Carboni E, Tanda GL, Frau R, Di Chiara G (September 1990). "Blockade of the noradrenaline carrier increases extracellular dopamine concentrations in the prefrontal cortex: evidence that dopamine is taken up in vivo by noradrenergic terminals". Journal of Neurochemistry. 55 (3): 1067–70. doi:10.1111/j.1471-4159.1990.tb04599.x. PMID 2117046. S2CID 23682303.

- ^ a b Vandenbergh DJ, Persico AM, Hawkins AL, Griffin CA, Li X, Jabs EW, Uhl GR (December 1992). "Human dopamine transporter gene (DAT1) maps to chromosome 5p15.3 and displays a VNTR". Genomics. 14 (4): 1104–6. doi:10.1016/S0888-7543(05)80138-7. PMID 1478653.

- ^ a b Schultz W (July 1998). "Predictive reward signal of dopamine neurons". Journal of Neurophysiology. 80 (1): 1–27. doi:10.1152/jn.1998.80.1.1. PMID 9658025.

- ^ Torres GE, Gainetdinov RR, Caron MG (January 2003). "Plasma membrane monoamine transporters: structure, regulation and function". Nature Reviews. Neuroscience. 4 (1): 13–25. doi:10.1038/nrn1008. PMID 12511858. S2CID 21545649.

- ^ Sonders MS, Zhu SJ, Zahniser NR, Kavanaugh MP, Amara SG (February 1997). "Multiple ionic conductances of the human dopamine transporter: the actions of dopamine and psychostimulants". The Journal of Neuroscience. 17 (3): 960–74. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-03-00960.1997. PMC 6573182. PMID 8994051.

- ^ a b Wheeler DD, Edwards AM, Chapman BM, Ondo JG (August 1993). "A model of the sodium dependence of dopamine uptake in rat striatal synaptosomes". Neurochemical Research. 18 (8): 927–36. doi:10.1007/BF00998279. PMID 8371835. S2CID 42196576.

- ^ a b c d e Cameron KN, Solis E, Ruchala I, De Felice LJ, Eltit JM (November 2015). "Amphetamine activates calcium channels through dopamine transporter-mediated depolarization". Cell Calcium. 58 (5): 457–66. doi:10.1016/j.ceca.2015.06.013. PMC 4631700. PMID 26162812.

One example of interest is CaMKII, which has been well characterized as an effector of Ca2+ currents downstream of L-type Ca2+ channels [21,22]. Interestingly, DAT is a CaMKII substrate and phosphorylated DAT favors the reverse transport of dopamine [48,49], constituting a possible mechanism by which electrical activity and L-type Ca2+ channels may modulate DAT states and dopamine release. ... In summary, our results suggest that pharmacologically, S(+)AMPH is more potent than DA at activating hDAT-mediated depolarizing currents, leading to L-type Ca2+ channel activation, and the S(+)AMPH-induced current is more tightly coupled than DA to open L-type Ca2+ channels.

- ^ a b Kilty JE, Lorang D, Amara SG (October 1991). "Cloning and expression of a cocaine-sensitive rat dopamine transporter". Science. 254 (5031): 578–9. Bibcode:1991Sci...254..578K. doi:10.1126/science.1948035. PMID 1948035.

- ^ Vaughan RA, Kuhar MJ (August 1996). "Dopamine transporter ligand binding domains. Structural and functional properties revealed by limited proteolysis". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 271 (35): 21672–80. doi:10.1074/jbc.271.35.21672. PMID 8702957.

- ^ Penmatsa A, Wang KH, Gouaux E (November 2013). "X-ray structure of dopamine transporter elucidates antidepressant mechanism". Nature. 503 (7474): 85–90. Bibcode:2013Natur.503...85P. doi:10.1038/nature12533. PMC 3904663. PMID 24037379.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Miller GM (January 2011). "The emerging role of trace amine-associated receptor 1 in the functional regulation of monoamine transporters and dopaminergic activity". Journal of Neurochemistry. 116 (2): 164–76. doi:10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.07109.x. PMC 3005101. PMID 21073468.

- ^ a b c Eiden LE, Weihe E (January 2011). "VMAT2: a dynamic regulator of brain monoaminergic neuronal function interacting with drugs of abuse". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1216 (1): 86–98. Bibcode:2011NYASA1216...86E. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05906.x. PMC 4183197. PMID 21272013.

- ^ Sulzer D, Cragg SJ, Rice ME (August 2016). "Striatal dopamine neurotransmission: regulation of release and uptake". Basal Ganglia. 6 (3): 123–148. doi:10.1016/j.baga.2016.02.001. PMC 4850498. PMID 27141430.

Despite the challenges in determining synaptic vesicle pH, the proton gradient across the vesicle membrane is of fundamental importance for its function. Exposure of isolated catecholamine vesicles to protonophores collapses the pH gradient and rapidly redistributes transmitter from inside to outside the vesicle. ... Amphetamine and its derivatives like methamphetamine are weak base compounds that are the only widely used class of drugs known to elicit transmitter release by a non-exocytic mechanism. As substrates for both DAT and VMAT, amphetamines can be taken up to the cytosol and then sequestered in vesicles, where they act to collapse the vesicular pH gradient.

- ^ Ledonne A, Berretta N, Davoli A, Rizzo GR, Bernardi G, Mercuri NB (July 2011). "Electrophysiological effects of trace amines on mesencephalic dopaminergic neurons". Front. Syst. Neurosci. 5: 56. doi:10.3389/fnsys.2011.00056. PMC 3131148. PMID 21772817.

Three important new aspects of TAs action have recently emerged: (a) inhibition of firing due to increased release of dopamine; (b) reduction of D2 and GABAB receptor-mediated inhibitory responses (excitatory effects due to disinhibition); and (c) a direct TA1 receptor-mediated activation of GIRK channels which produce cell membrane hyperpolarization.

- ^ "TAAR1". GenAtlas. University of Paris. 28 January 2012. Retrieved 29 May 2014.

• tonically activates inwardly rectifying K(+) channels, which reduces the basal firing frequency of dopamine (DA) neurons of the ventral tegmental area (VTA)

- ^ a b Underhill SM, Wheeler DS, Li M, Watts SD, Ingram SL, Amara SG (July 2014). "Amphetamine modulates excitatory neurotransmission through endocytosis of the glutamate transporter EAAT3 in dopamine neurons". Neuron. 83 (2): 404–416. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2014.05.043. PMC 4159050. PMID 25033183.

AMPH also increases intracellular calcium (Gnegy et al., 2004) that is associated with calmodulin/CamKII activation (Wei et al., 2007) and modulation and trafficking of the DAT (Fog et al., 2006; Sakrikar et al., 2012).

- ^ a b c Vaughan RA, Foster JD (September 2013). "Mechanisms of dopamine transporter regulation in normal and disease states". Trends in Pharmacological Sciences. 34 (9): 489–96. doi:10.1016/j.tips.2013.07.005. PMC 3831354. PMID 23968642.

AMPH and METH also stimulate DA efflux, which is thought to be a crucial element in their addictive properties [80], although the mechanisms do not appear to be identical for each drug [81]. These processes are PKCβ– and CaMK–dependent [72, 82], and PKCβ knock-out mice display decreased AMPH-induced efflux that correlates with reduced AMPH-induced locomotion [72].

- ^ Ciliax BJ, Drash GW, Staley JK, Haber S, Mobley CJ, Miller GW, Mufson EJ, Mash DC, Levey AI (June 1999). "Immunocytochemical localization of the dopamine transporter in human brain". The Journal of Comparative Neurology. 409 (1): 38–56. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19990621)409:1<38::AID-CNE4>3.0.CO;2-1. PMID 10363710.

- ^ Liu Z, Yan SF, Walker JR, Zwingman TA, Jiang T, Li J, Zhou Y (April 2007). "Study of gene function based on spatial co-expression in a high-resolution mouse brain atlas". BMC Systems Biology. 1: 19. doi:10.1186/1752-0509-1-19. PMC 1863433. PMID 17437647.

- ^ Maguire JJ, Davenport AP (19 July 2016). "Trace amine receptor: TA1 receptor". IUPHAR/BPS Guide to PHARMACOLOGY. International Union of Basic and Clinical Pharmacology. Retrieved 22 September 2016.

- ^ Nirenberg MJ, Vaughan RA, Uhl GR, Kuhar MJ, Pickel VM (January 1996). "The dopamine transporter is localized to dendritic and axonal plasma membranes of nigrostriatal dopaminergic neurons". The Journal of Neuroscience. 16 (2): 436–47. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-02-00436.1996. PMC 6578661. PMID 8551328.

- ^ Hersch SM, Yi H, Heilman CJ, Edwards RH, Levey AI (November 1997). "Subcellular localization and molecular topology of the dopamine transporter in the striatum and substantia nigra". The Journal of Comparative Neurology. 388 (2): 211–27. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19971117)388:2<211::AID-CNE3>3.0.CO;2-4. PMID 9368838.

- ^ Kawarai T, Kawakami H, Yamamura Y, Nakamura S (August 1997). "Structure and organization of the gene encoding human dopamine transporter". Gene. 195 (1): 11–8. doi:10.1016/S0378-1119(97)00131-5. PMID 9300814.

- ^ Sano A, Kondoh K, Kakimoto Y, Kondo I (May 1993). "A 40-nucleotide repeat polymorphism in the human dopamine transporter gene". Human Genetics. 91 (4): 405–6. doi:10.1007/BF00217369. PMID 8500798. S2CID 39416578.

- ^ Miller GM, Madras BK (2002). "Polymorphisms in the 3'-untranslated region of human and monkey dopamine transporter genes affect reporter gene expression". Molecular Psychiatry. 7 (1): 44–55. doi:10.1038/sj/mp/4000921. PMID 11803445.

- ^ Sacchetti P, Mitchell TR, Granneman JG, Bannon MJ (March 2001). "Nurr1 enhances transcription of the human dopamine transporter gene through a novel mechanism". Journal of Neurochemistry. 76 (5): 1565–72. doi:10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00181.x. PMID 11238740. S2CID 19410051.

- ^ Morón JA, Zakharova I, Ferrer JV, Merrill GA, Hope B, Lafer EM, Lin ZC, Wang JB, Javitch JA, Galli A, Shippenberg TS (September 2003). "Mitogen-activated protein kinase regulates dopamine transporter surface expression and dopamine transport capacity". The Journal of Neuroscience. 23 (24): 8480–8. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-24-08480.2003. PMC 6740378. PMID 13679416.

- ^ Pristupa ZB, McConkey F, Liu F, Man HY, Lee FJ, Wang YT, Niznik HB (September 1998). "Protein kinase-mediated bidirectional trafficking and functional regulation of the human dopamine transporter". Synapse. 30 (1): 79–87. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1098-2396(199809)30:1<79::AID-SYN10>3.0.CO;2-K. PMID 9704884.

- ^ Lindemann L, Ebeling M, Kratochwil NA, Bunzow JR, Grandy DK, Hoener MC (March 2005). "Trace amine-associated receptors form structurally and functionally distinct subfamilies of novel G protein-coupled receptors". Genomics. 85 (3): 372–85. doi:10.1016/j.ygeno.2004.11.010. PMID 15718104.

- ^ Maguire JJ, Parker WA, Foord SM, Bonner TI, Neubig RR, Davenport AP (March 2009). "International Union of Pharmacology. LXXII. Recommendations for trace amine receptor nomenclature". Pharmacological Reviews. 61 (1): 1–8. doi:10.1124/pr.109.001107. PMC 2830119. PMID 19325074.

- ^ Krause J (April 2008). "SPECT and PET of the dopamine transporter in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder". Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics. 8 (4): 611–25. doi:10.1586/14737175.8.4.611. PMID 18416663. S2CID 24589993.

Zinc binds at ... extracellular sites of the DAT [103], serving as a DAT inhibitor. In this context, controlled double-blind studies in children are of interest, which showed positive effects of zinc [supplementation] on symptoms of ADHD [105,106]. It should be stated that at this time [supplementation] with zinc is not integrated in any ADHD treatment algorithm.

- ^ Sulzer D (February 2011). "How addictive drugs disrupt presynaptic dopamine neurotransmission". Neuron. 69 (4): 628–49. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2011.02.010. PMC 3065181. PMID 21338876.

They did not confirm the predicted straightforward relationship between uptake and release, but rather that some compounds including AMPH were better releasers than substrates for uptake. Zinc, moreover, stimulates efflux of intracellular [3H]DA despite its concomitant inhibition of uptake (Scholze et al., 2002).

- ^ a b Scholze P, Nørregaard L, Singer EA, Freissmuth M, Gether U, Sitte HH (June 2002). "The role of zinc ions in reverse transport mediated by monoamine transporters". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 277 (24): 21505–13. doi:10.1074/jbc.M112265200. PMID 11940571.

The human dopamine transporter (hDAT) contains an endogenous high affinity Zn2+ binding site with three coordinating residues on its extracellular face (His193, His375, and Glu396). ... Although Zn2+ inhibited uptake, Zn2+ facilitated [3H]MPP+ release induced by amphetamine, MPP+, or K+-induced depolarization specifically at hDAT but not at the human serotonin and the norepinephrine transporter (hNET).

- ^ Scassellati C, Bonvicini C, Faraone SV, Gennarelli M (October 2012). "Biomarkers and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a systematic review and meta-analyses". Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 51 (10): 1003–1019.e20. doi:10.1016/j.jaac.2012.08.015. PMID 23021477.

With regard to zinc supplementation, a placebo controlled trial reported that doses up to 30 mg/day of zinc were safe for at least 8 weeks, but the clinical effect was equivocal except for the finding of a 37% reduction in amphetamine optimal dose with 30 mg per day of zinc.110

- ^ Gainetdinov RR, Wetsel WC, Jones SR, Levin ED, Jaber M, Caron MG (January 1999). "Role of serotonin in the paradoxical calming effect of psychostimulants on hyperactivity". Science. 283 (5400): 397–401. Bibcode:1999Sci...283..397G. doi:10.1126/science.283.5400.397. PMID 9888856. S2CID 9629915.

- ^ Greenwood TA, Alexander M, Keck PE, McElroy S, Sadovnick AD, Remick RA, Kelsoe JR (March 2001). "Evidence for linkage disequilibrium between the dopamine transporter and bipolar disorder". American Journal of Medical Genetics. 105 (2): 145–51. doi:10.1002/1096-8628(2001)9999:9999<::AID-AJMG1161>3.0.CO;2-8. PMID 11304827.

- ^ Yang B, Chan RC, Jing J, Li T, Sham P, Chen RY (June 2007). "A meta-analysis of association studies between the 10-repeat allele of a VNTR polymorphism in the 3'-UTR of dopamine transporter gene and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder". American Journal of Medical Genetics. Part B, Neuropsychiatric Genetics. 144B (4): 541–50. doi:10.1002/ajmg.b.30453. PMID 17440978. S2CID 22881996.

- ^ Sander T, Harms H, Podschus J, Finckh U, Nickel B, Rolfs A, Rommelspacher H, Schmidt LG (February 1997). "Allelic association of a dopamine transporter gene polymorphism in alcohol dependence with withdrawal seizures or delirium". Biological Psychiatry. 41 (3): 299–304. doi:10.1016/S0006-3223(96)00044-3. PMID 9024952. S2CID 42947314.

- ^ Ueno S, Nakamura M, Mikami M, Kondoh K, Ishiguro H, Arinami T, Komiyama T, Mitsushio H, Sano A, Tanabe H (November 1999). "Identification of a novel polymorphism of the human dopamine transporter (DAT1) gene and the significant association with alcoholism". Molecular Psychiatry. 4 (6): 552–7. doi:10.1038/sj.mp.4000562. PMID 10578237.

- ^ Ueno S (February 2003). "Genetic polymorphisms of serotonin and dopamine transporters in mental disorders". The Journal of Medical Investigation. 50 (1–2): 25–31. PMID 12630565.

- ^ Beaver KM, Wright JP, DeLisi M (September 2008). "Delinquent peer group formation: evidence of a gene x environment correlation". The Journal of Genetic Psychology. 169 (3): 227–44. doi:10.3200/GNTP.169.3.227-244. PMID 18788325. S2CID 46592146.

- ^ Florida State University (2 October 2008). "Specific Gene Found In Adolescent Men With Delinquent Peers". ScienceDaily. Retrieved 8 October 2008.

- ^ Laasonen-Balk T, Kuikka J, Viinamäki H, Husso-Saastamoinen M, Lehtonen J, Tiihonen J (June 1999). "Striatal dopamine transporter density in major depression". Psychopharmacology. 144 (3): 282–5. doi:10.1007/s002130051005. PMID 10435396. S2CID 32882588.

- ^ Ng J, Zhen J, Meyer E, Erreger K, Li Y, Kakar N, Ahmad J, Thiele H, Kubisch C, Rider NL, Morton DH, Strauss KA, Puffenberger EG, D'Agnano D, Anikster Y, Carducci C, Hyland K, Rotstein M, Leuzzi V, Borck G, Reith ME, Kurian MA (April 2014). "Dopamine transporter deficiency syndrome: phenotypic spectrum from infancy to adulthood". Brain. 137 (Pt 4): 1107–19. doi:10.1093/brain/awu022. PMC 3959557. PMID 24613933.

- ^ Rothman RB, Ananthan S, Partilla JS, Saini SK, Moukha-Chafiq O, Pathak V, Baumann MH (June 2015). "Studies of the biogenic amine transporters 15. Identification of novel allosteric dopamine transporter ligands with nanomolar potency". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 353 (3): 529–38. doi:10.1124/jpet.114.222299. PMC 4429677. PMID 25788711.

- ^ Aggarwal S, Liu X, Rice C, Menell P, Clark PJ, Paparoidamis N, Xiao YC, Salvino JM, Fontana AC, España RA, Kortagere S, Mortensen OV (2019). "Identification of a Novel Allosteric Modulator of the Human Dopamine Transporter". ACS Chem Neurosci. 10 (8): 3718–3730. doi:10.1021/acschemneuro.9b00262. PMC 6703927. PMID 31184115.

- ^ Wersinger C, Sidhu A (April 2003). "Attenuation of dopamine transporter activity by alpha-synuclein". Neuroscience Letters. 340 (3): 189–92. doi:10.1016/S0304-3940(03)00097-1. PMID 12672538. S2CID 54381509.

- ^ Lee FJ, Liu F, Pristupa ZB, Niznik HB (April 2001). "Direct binding and functional coupling of alpha-synuclein to the dopamine transporters accelerate dopamine-induced apoptosis". FASEB Journal. 15 (6): 916–26. doi:10.1096/fj.00-0334com. PMID 11292651.

- ^ Torres GE, Yao WD, Mohn AR, Quan H, Kim KM, Levey AI, Staudinger J, Caron MG (April 2001). "Functional interaction between monoamine plasma membrane transporters and the synaptic PDZ domain-containing protein PICK1". Neuron. 30 (1): 121–34. doi:10.1016/S0896-6273(01)00267-7. PMID 11343649. S2CID 17318937.

- ^ Carneiro AM, Ingram SL, Beaulieu JM, Sweeney A, Amara SG, Thomas SM, Caron MG, Torres GE (August 2002). "The multiple LIM domain-containing adaptor protein Hic-5 synaptically colocalizes and interacts with the dopamine transporter". The Journal of Neuroscience. 22 (16): 7045–54. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-16-07045.2002. PMC 6757888. PMID 12177201.

- ^ Midde NM, Yuan Y, Quizon PM, Sun WL, Huang X, Zhan CG, Zhu J (March 2015). "Mutations at tyrosine 88, lysine 92 and tyrosine 470 of human dopamine transporter result in an attenuation of HIV-1 Tat-induced inhibition of dopamine transport". Journal of Neuroimmune Pharmacology. 10 (1): 122–35. doi:10.1007/s11481-015-9583-3. PMC 4388869. PMID 25604666.

- ^ Midde NM, Huang X, Gomez AM, Booze RM, Zhan CG, Zhu J (September 2013). "Mutation of tyrosine 470 of human dopamine transporter is critical for HIV-1 Tat-induced inhibition of dopamine transport and transporter conformational transitions". Journal of Neuroimmune Pharmacology. 8 (4): 975–87. doi:10.1007/s11481-013-9464-6. PMC 3740080. PMID 23645138.

- ^ Purohit V, Rapaka R, Shurtleff D (August 2011). "Drugs of abuse, dopamine, and HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders/HIV-associated dementia". Molecular Neurobiology. 44 (1): 102–10. doi:10.1007/s12035-011-8195-z. PMID 21717292. S2CID 13319355.

외부 링크

- 도파민 운반체 관련 협회, 실험, 간행물 및 임상시험

- 미국 국립 의학 도서관의 도파민+트랜스포터(MesH)

- UniProtect에 대해 PDB에서 사용할 수 있는 모든 구조 정보의 개요: PDBe-KB에서 Q7K4Y6(Drosophila 멜라노가스터 나트륨 의존도 도파민 트랜스포터.