덱스메틸페니다이트

Dexmethylphenidate | |

| |

| 임상 데이터 | |

|---|---|

| 상호 | 포컬린, 포컬린 XR 등 |

| 기타 이름 | d-트레오메틸페니다이트(D-TMP) |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | 모노그래프 |

| Medline Plus | a603014 |

| 라이선스 데이터 | |

| 의존성 책임 | 물리:심리학적 문제 없음:높은 |

| 루트 행정부. | 입으로 |

| ATC 코드 | |

| 법적 상태 | |

| 법적 상태 | |

| 약동학 데이터 | |

| 바이오 어베이러빌리티 | 11–52% |

| 단백질 결합 | 30% |

| 대사 | 간 |

| 반감기 제거 | 4시간 |

| 배설물 | 신장 |

| 식별자 | |

| |

| CAS 번호 |

|

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| 드러그뱅크 |

|

| 켐스파이더 | |

| 유니 |

|

| 케그 | |

| 체비 | |

| 첸블 |

|

| CompTox 대시보드 (EPA ) | |

| 화학 및 물리 데이터 | |

| 공식 | C14H19NO2 |

| 몰 질량 | 233.311 g/120−1 |

| 3D 모델(JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| | |

덱스메틸페니데이트(Dexmethylphenidate)는 포컬린(Focialin)이라는 브랜드명으로 판매되며 [3]5세 이상의 주의력결핍과잉행동장애(ADHD)를 치료하기 위해 사용되는 의약품이다.4주가 지나도 아무런 효과가 나타나지 않으면 사용을 [3]중단하는 것이 합리적입니다.입으로 [3]먹는 거예요.즉시 릴리스 방식은 최대 5시간 [4]동안 지속되며 확장 릴리스 방식은 최대 12시간 동안 지속됩니다.

일반적인 부작용으로는 복통, 식욕부진, [3]발열 등이 있다.심각한 부작용으로는 학대, 정신병, 갑작스런 심장사, 조증, 과민증, 발작, 그리고 위험한 장기 [3]발기가 포함될 수 있다.임신과 모유 수유 중 안전성은 [5]불분명하다.덱스메틸페니데이트는 중추신경계(CNS) 자극제이다.[6][3]ADHD에서 어떻게 작동하는지는 불분명하다.[3]그것은 메틸페니다이트의 [3]보다 활성적인 에난티오머이다.

덱스메틸페니데이트는 [1]2001년 미국에서 의료용으로 승인되었다.제네릭 [3]의약품으로 구입할 수 있습니다.2019년에는 미국에서 131번째로 많이 처방된 의약품으로 500만 건 이상의 [7][8]처방을 받았다.그것은 [9]스위스에서도 이용할 수 있다.

의료 용도

덱스메틸페니데이트는 보통 심리, 교육, 행동 또는 다른 형태의 치료와 함께 ADHD 치료제로 사용된다.각성제는 사용자가 집중하기 쉽고, 산만함을 피하고, 행동을 통제하기 쉽게 함으로써 ADHD 증상을 개선하는 데 도움을 줄 것을 제안한다.위약 대조군 시험 결과, 1일 1회 덱스메틸페니데이트 XR이 효과적이고 일반적으로 잘 [6]내성이 있는 것으로 나타났다.

어린이의 ADHD 증상 개선은 [6]위약 대비 덱스메틸페니데이트 XR의 경우 유의미하게 컸다.또한 실험실 강의실 전반기 동안 OROS(삼투압 제어 방출 경구 전달 시스템) 메틸페니다이트보다 더 높은 효과를 보였지만, 당일 후반 평가에서는 OROS 메틸페니다이트가 [6]선호되었다.

금지 사항

메틸페니데이트는 모노아민 산화효소 억제제(예: 페넬진 및 트라닐시프로민)를 사용하는 개인 또는 교반, 틱스, 녹내장 또는 메틸페니데이트 [10]약물에 포함된 성분에 대한 과민증을 가진 개인에게 금지된다.

임산부들은 잠재적 [11]위험을 초과하는 유익성이 있는 경우에만 그 약을 사용할 것을 권고받고 있다.메틸페니데이트가 태아 [12]발달에 미치는 영향을 결정적으로 입증하기 위한 충분한 인간 연구가 수행되지 않았다.2018년 리뷰에서는 쥐와 토끼에서 기형성이 없으며 "인간의 주요 기형성이 아니다"[13]라는 결론을 내렸다.

부작용

덱스메틸페니데이트를 함유하는 제품은 메틸페니데이트를 [14]함유하는 것에 필적하는 부작용 프로파일을 가진다.

전반적으로, 장시간 작용 MPH 제제와 관련된 부작용은 식욕 상실, 입가 건조, 불안/신경성, 메스꺼움 및 불면증을 포함한 가장 일반적인 부작용과 유사하다[16].위장 부작용에는 복통과 체중 감소가 포함될 수 있다.신경계 부작용으로는 무지외반증, 과민성, 운동장애, 구강디스토니아,[17] 무기력증, 현기증 등이 있을 수 있다.심장 부작용으로는 두근거림, 혈압 및 심박수 변화(일반적으로 경미함), 빈맥(급속 심박수)[18] 등이 있을 수 있습니다.메틸페니데이트를 복용하는 ADHD를 가진 흡연자들은 니코틴 의존도를 높일 수 있으며, 니코틴 욕구가 증가하고 하루 [19]평균 1.3개비의 담배가 늘어나면서 메틸페니데이트를 사용하기 전보다 더 자주 담배를 피운다.안과적 부작용으로는 동공확장 및 안구건조증으로 인한 시야 흐릿함이 포함될 수 있으며, 복시 및 산드라이아시스의 [20][21]빈도가 낮은 것으로 보고될 수 있다.

어린이의 [22]장기 치료와 함께 키가 약간 감소했다는 증거가 있다.이는 처음 3년간 연간 1cm(0.4인치) 이하로 추정되며, 10년간 [23][24]총 3cm(1.2인치) 감소한다.

경피 메틸페니데이트를 사용할 때 과민성(피부 발진, 두드러기, 발열 포함)이 보고되는 경우가 있습니다.데이트라나 패치는 경구 [25]메틸페니다이트보다 피부 반응 속도가 훨씬 높습니다.

메틸페니다이트는 정신이상자의 정신질환을 악화시킬 수 있으며, 매우 드문 경우 새로운 [26]정신이상 증상의 출현과 관련이 있다.조증이나 [27]저감증의 잠재적 유도로 인해 조울증이 있는 사람에게 극도의 주의를 기울여 사용해야 한다.자살에 대한 매우 드문 보고가 있었지만, 일부 저자들은 증거가 [22]연관성을 뒷받침하지 않는다고 주장한다.로고르헤아는 때때로 보고된다.성욕 장애, 방향 감각 상실, 시각 환각은 거의 [20]보고되지 않는다.프리아피즘은 잠재적으로 [28]심각할 수 있는 매우 드문 부작용이다.

미국 식품의약국이 2011년에 의뢰한 연구에 따르면 어린이, 청소년 및 성인의 경우 심각한 심혈관 장애(급사, 심장마비 및 뇌졸중)와 메틸페니다이트 또는 기타 ADHD 자극제의 [29]의학적 사용 사이에는 연관성이 없는 것으로 나타났다.

일부 부작용은 메틸페니데이트의 만성 사용 시에만 나타날 수 있으므로 부작용에 대한 지속적인 관찰이 [30]권장된다.

2018년 코크란 리뷰는 메틸페니다이트가 심장 문제, 정신 질환, 죽음과 같은 심각한 부작용과 관련이 있을 수 있다는 것을 발견했다.증거의 확실성은 매우 [31]낮다고 언급되었다.

2018년 검토 결과 [32]아동에게 심각한 부작용과 심각하지 않은 부작용을 둘 다 일으킬 수 있다는 잠정적인 증거가 발견되었다.

과다 복용

메틸페니데이트에 대한 중간급성 과다복용의 증상은 주로 중추신경계 과잉자극에서 발생한다. 이러한 증상들은 구토, 메스꺼움, 흥분, 과반사, 근육경련, 행복감, 혼란, 환각, 섬망, 온열증, 발한, 발한, 두통, 빈맥, 심장박동, 심장박동, 심장박동 등을 포함한다.부정맥,[10][33] 고혈압, 산드라이아시스, 점막건조증 등이 있습니다.심각한 과다 복용은 과열증, 교감 자극 독성 물질, 경련, 편집증, 고정관념, 횡문근융해증, 혼수, 순환기 [10][33][34]붕괴와 같은 증상을 포함할 수 있습니다.메틸페니데이트 과다 복용은 적절한 [34]치료로 치명적인 경우가 드물다.동맥에 메틸페니데이트 정제를 주입한 후 농양 형성 및 괴사를 포함한 심각한 독성 반응이 [35]보고되었다.

메틸페니다트 과다 복용의 치료에는 일반적으로 항정신병 약물, α-아드레노셉터 작용제 및 프로포폴이 2차 [34]치료제로 사용되는 벤조디아제핀의 투여가 포함된다.

중독과 의존

메틸페니다이트는 암페타민과 유사한 중독성과 의존성을 가진 자극제이다.그것은 중독성 [38][39]약물 중 적당한 영향을 가지고 있다. 따라서, 중독과 심리적 의존은 가능하고, 레크리에이션 [39][40]약으로 메틸페니데이트를 고용량으로 사용할 때 가능성이 높다.의료용량 범위 이상으로 사용할 경우 각성제는 각성제 정신병의 [41]발병과 관련이 있습니다.모든 중독성 약물과 마찬가지로, 핵의 D1형 중가시 뉴런에서 δFosB의 과잉발현은 메틸페니다트 [40][42]중독과 관련이 있다.

생체 분자 메커니즘

메틸페니데이트는 뇌의 보상 시스템에서 [42]약역학적 효과(즉, 도파민 재흡입 억제)로 인해 행복감을 유도할 가능성이 있다.치료상의 복용량은, 주의력 결핍 과잉 행동 장애를 충분히 필요한 중핵 accumbens의 뉴런 spiny ΔFosB 유전자 발현의 D1-type 중간에 있어 계속적인 증가를 초래할 흔히 처방되는 양이 지시하는[39][42][43]결과적으로, 사마르칸트 보상 체계 또는 특정의 보상 경로, 활성화되지는 않는다.그 tr에ADHD의 섭취, 메틸페니다이트의 사용은 [39][42][43]중독을 일으킬 수 있는 능력이 부족하다.단, 메틸페니데이트가 생체이용 가능한 투여경로(예를 들어 인서플레이션 또는 정맥투여)를 통해 충분히 높은 레크리에이션 용량으로 사용될 경우, 특히 행복제로서의 약물 사용에 대해 δFosB가 핵에 축적된다.[39][42]따라서 다른 중독성 약물과 마찬가지로 메틸페니데이트의 정기적인 레크리에이션 사용은 결국 D1형 뉴런에서 δFosB 과발현을 유발하고,[42][43][44] 이는 중독을 유도하는 일련의 유전자 전사 매개 시그널링 캐스케이드를 유발한다.

과다 복용

메틸페니데이트에 대한 중간급성 과다복용의 증상은 주로 중추신경계 과잉자극에서 발생한다. 이러한 증상들은 구토, 메스꺼움, 흥분, 과반사, 근육경련, 행복감, 혼란, 환각, 섬망, 온열증, 발한, 발한, 두통, 빈맥, 심장박동, 심장박동, 심장박동 등을 포함한다.부정맥,[10][33] 고혈압, 산드라이아시스, 점막건조증 등이 있습니다.심각한 과다 복용은 과열증, 교감 자극 독성 물질, 경련, 편집증, 고정관념, 횡문근융해증, 혼수, 순환기 [10][33][34]붕괴와 같은 증상을 포함할 수 있습니다.메틸페니데이트 과다 복용은 적절한 [34]치료로 치명적인 경우가 드물다.동맥에 메틸페니데이트 정제를 주입한 후 농양 형성 및 괴사를 포함한 심각한 독성 반응이 [35]보고되었다.

메틸페니다트 과다 복용의 치료에는 일반적으로 항정신병 약물, α-아드레노셉터 작용제 및 프로포폴이 2차 [34]치료제로 사용되는 벤조디아제핀의 투여가 포함된다.

상호 작용

메틸페니데이트는 비타민 K 항응고제, 특정 항경련제 및 일부 항우울제(삼환식 항우울제, 선택적 세로토닌 재흡수 억제제)의 대사를 억제할 수 있다.병행 투여는 혈장 약물 [45]농도 모니터링의 도움을 받아 선량 조정이 필요할 수 있다.항우울제 [46][47][48][49]투여와 함께 세로토닌 신드롬을 유발하는 메틸페니다이트에 대한 여러 사례 보고가 있다.

메틸페니데이트가 에탄올과 혼합될 때, 코카인과 에탄올에서 코카틸렌의 간 형성과는 달리 에틸페니데이트라고 불리는 대사물이 간 전이를 [50][51]통해 형성된다.에틸페니다이트의 효력 감소와 그 경미한 형성은 치료용량에서 약리학적 프로파일에 기여하지 않으며, 과다 복용의 경우에도 에틸페니다이트 농도는 무시할 [52][51]수 있는 수준으로 유지됨을 의미한다.

알코올(에탄올)의 코잉제이션은 또한 d-메틸페니다이트의 혈장 수치를 최대 40%[53]까지 증가시킵니다.

메틸페니다이트로부터 간 독성은 극히 드물지만, 메틸페니다이트와 함께 β-아드레날린 작용제를 섭취하면 간 [54]독성의 위험이 증가할 수 있다는 제한된 증거가 있다.

액티비티 모드

메틸페니다이트는 카테콜아민을 시냅스, 특히 선조체 및 메소림빅계에서 [56]카테콜아민을 제거하는 역할을 하는 도파민 트랜스포터(DAT) 및 노르에피네프린 트랜스포터(NET)[55]를 억제함으로써 카테콜아민 재흡입 억제제이다.게다가, 그것은 "이 모노아민의 외부 공간으로의 [2]방출을 증가시킨다"고 생각됩니다.

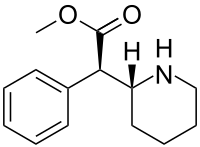

메틸페니다이트(MPH)의 4가지 입체 이성질체가 가능하지만, 현대에는 트레오 디아스테레오 이성질체만이 사용된다.덱스메틸페니다이트(d-threo-methylphenidate)는 메틸페니다이트([57][58]methylphenidate)의 RR 에난티오머의 제제이다.이론적으로 D-TMP(d-threo-메틸페니다이트)는 라세믹 [55][59]생성물의 2배 강도를 기대할 수 있다.

| 컴팩트[60] | DAT(Ki) | DA(IC50) | 네트워크(Ki) | NE(IC50) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| D-TMP | 161 | 23 | 206 | 39 |

| L-TMP | 2250 | 1600 | 10,000 이상 | 980 |

| DL-TMP | 121 | 20 | 788 | 51 |

약리학

Dexmethylphenidate는 4-6시간의 효과 지속 시간을 가진다(장시간 작용 제제인 Focialin XR도 이용 가능하며, 12시간에 걸쳐 사용할 수 있으며 DL(덱스트로-, 레보-)-TMP(Threo-methylphenidate) XR(Concerta, rital과 함께 확장 방출)만큼 효과적인 것으로 나타났다).또한 어린이와 [64]성인 모두에서[63] ADHD 증상을 감소시키는 것으로 입증되었습니다. d-MPH는 MPH와 유사한[14] 부작용 프로파일을 가지고 있으며 음식 [65]섭취에 관계없이 투여할 수 있습니다.

「 」를 참조해 주세요.

레퍼런스

- ^ a b "Focalin- dexmethylphenidate hydrochloride tablet". DailyMed. 24 June 2020. Retrieved 15 November 2020.

- ^ a b "Focalin XR- dexmethylphenidate hydrochloride capsule, extended release". DailyMed. 27 June 2020. Retrieved 15 November 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Dexmethylphenidate Hydrochloride Monograph for Professionals". Drugs.com. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Retrieved 15 April 2019.

- ^ Mosby's Drug Reference for Health Professions - E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences. 2013. p. 455. ISBN 9780323187602.

- ^ "Dexmethylphenidate Use During Pregnancy". Drugs.com. Retrieved 15 April 2019.

- ^ a b c d Moen MD, Keam SJ (December 2009). "Dexmethylphenidate extended release: a review of its use in the treatment of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder". CNS Drugs. 23 (12): 1057–83. doi:10.2165/11201140-000000000-00000. PMID 19958043. S2CID 24975170.

- ^ "The Top 300 of 2019". ClinCalc. Retrieved 16 October 2021.

- ^ "Dexmethylphenidate Hydrochloride - Drug Usage Statistics". ClinCalc. Retrieved 16 October 2021.

- ^ "Focalin XR". Drugs.com. Retrieved 15 April 2019.

- ^ a b c d e "Daytrana- methylphenidate patch". DailyMed. 15 June 2021. Retrieved 26 March 2022.

- ^ "Methylphenidate: Use During Pregnancy and Breastfeeding". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 2 January 2018.

- ^ Humphreys C, Garcia-Bournissen F, Ito S, Koren G (July 2007). "Exposure to attention deficit hyperactivity disorder medications during pregnancy". Canadian Family Physician. 53 (7): 1153–1155. PMC 1949295. PMID 17872810.

- ^ Ornoy A (February 2018). "Pharmacological Treatment of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder During Pregnancy and Lactation". Pharmaceutical Research. 35 (3): 46. doi:10.1007/s11095-017-2323-z. PMID 29411149. S2CID 3663423.

- ^ a b Keating GM, Figgitt DP (2002). "Dexmethylphenidate". Drugs. 62 (13): 1899–904, discussion 1905–8. doi:10.2165/00003495-200262130-00009. PMID 12215063. S2CID 249894173.

- ^ Nutt D, King LA, Saulsbury W, Blakemore C (March 2007). "Development of a rational scale to assess the harm of drugs of potential misuse". Lancet. 369 (9566): 1047–1053. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60464-4. PMID 17382831. S2CID 5903121.

- ^ Coghill D, Banaschewski T, Zuddas A, Pelaz A, Gagliano A, Doepfner M (September 2013). "Long-acting methylphenidate formulations in the treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a systematic review of head-to-head studies". BMC Psychiatry. Springer Science and Business Media LLC. 13 (1): 237. doi:10.1186/1471-244x-13-237. PMC 3852277. PMID 24074240.

- ^ Rissardo JP, Caprara AL (2020). "Oromandibular dystonia secondary to methylphenidate: A case report and literature review". Int Arch Health Sci. 7: 108–111. doi:10.4103/iahs.iahs_71_19 (inactive 28 February 2022). Archived from the original on 15 November 2021. Retrieved 15 November 2021 – via Gale Academic OneFile.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 유지 : 2022년 2월 현재 DOI 비활성화 (링크) - ^ "Ritalin LA (methylphenidate hydrochloride) extended-release capsules" (PDF). Novartis. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 July 2011.

- ^ Bron TI, Bijlenga D, Kasander MV, Spuijbroek AT, Beekman AT, Kooij JJ (June 2013). "Long-term relationship between methylphenidate and tobacco consumption and nicotine craving in adults with ADHD in a prospective cohort study". European Neuropsychopharmacology. 23 (6): 542–554. doi:10.1016/j.euroneuro.2012.06.004. PMID 22809706. S2CID 23148548.

- ^ a b De Sousa A, Kalra G (January 2012). "Drug therapy of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: current trends". Mens Sana Monographs. 10 (1): 45–69. doi:10.4103/0973-1229.87261. PMC 3353606. PMID 22654382.

- ^ Jaanus SD (1992). "Ocular side effects of selected systemic drugs". Optometry Clinics. 2 (4): 73–96. PMID 1363080.

- ^ a b Cortese S, Holtmann M, Banaschewski T, Buitelaar J, Coghill D, Danckaerts M, et al. (March 2013). "Practitioner review: current best practice in the management of adverse events during treatment with ADHD medications in children and adolescents". Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines. 54 (3): 227–246. doi:10.1111/jcpp.12036. PMID 23294014.

- ^ Poulton A (August 2005). "Growth on stimulant medication; clarifying the confusion: a review". Archives of Disease in Childhood. 90 (8): 801–806. doi:10.1136/adc.2004.056952. PMC 1720538. PMID 16040876.

- ^ Hinshaw SP, Arnold LE (January 2015). "ADHD, Multimodal Treatment, and Longitudinal Outcome: Evidence, Paradox, and Challenge". Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews. Cognitive Science. 6 (1): 39–52. doi:10.1002/wcs.1324. PMC 4280855. PMID 25558298.

- ^ Findling RL, Dinh S (March 2014). "Transdermal therapy for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder with the methylphenidate patch (MTS)". CNS Drugs. 28 (3): 217–228. doi:10.1007/s40263-014-0141-y. PMC 3933749. PMID 24532028.

- ^ Kraemer M, Uekermann J, Wiltfang J, Kis B (July 2010). "Methylphenidate-induced psychosis in adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: report of 3 new cases and review of the literature". Clinical Neuropharmacology. 33 (4): 204–206. doi:10.1097/WNF.0b013e3181e29174. PMID 20571380. S2CID 34956456.

- ^ Wingo AP, Ghaemi SN (2008). "Frequency of stimulant treatment and of stimulant-associated mania/hypomania in bipolar disorder patients". Psychopharmacology Bulletin. 41 (4): 37–47. PMID 19015628.

- ^ "Methylphenidate ADHD Medications: Drug Safety Communication – Risk of Long-lasting Erections". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 17 December 2013. Archived from the original on 17 December 2013. Retrieved 17 December 2013.

- ^ "FDA Drug Safety Communication: Safety Review Update of Medications used to treat Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) in children and young adults". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 20 December 2011. Archived from the original on 30 October 2013. Retrieved 4 November 2013.

• Cooper WO, Habel LA, Sox CM, Chan KA, Arbogast PG, Cheetham TC, et al. (November 2011). "ADHD drugs and serious cardiovascular events in children and young adults". The New England Journal of Medicine. 365 (20): 1896–1904. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1110212. PMC 4943074. PMID 22043968.

• "FDA Drug Safety Communication: Safety Review Update of Medications used to treat Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) in adults". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 15 December 2011. Archived from the original on 30 October 2013. Retrieved 4 November 2013.

• Habel LA, Cooper WO, Sox CM, Chan KA, Fireman BH, Arbogast PG, et al. (December 2011). "ADHD medications and risk of serious cardiovascular events in young and middle-aged adults". JAMA. 306 (24): 2673–2683. doi:10.1001/jama.2011.1830. PMC 3350308. PMID 22161946. - ^ Gordon N (1999). "Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: possible causes and treatment". International Journal of Clinical Practice. 53 (7): 524–528. PMID 10692738.

- ^ Storebø OJ, Pedersen N, Ramstad E, Kielsholm ML, Nielsen SS, Krogh HB, et al. (May 2018). "Methylphenidate for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in children and adolescents - assessment of adverse events in non-randomised studies". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 5: CD012069. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012069.pub2. PMC 6494554. PMID 29744873.

- ^ Storebø OJ, Pedersen N, Ramstad E, Kielsholm ML, Nielsen SS, Krogh HB, et al. (May 2018). "Methylphenidate for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in children and adolescents - assessment of adverse events in non-randomised studies". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (Systematic Review). 5: CD012069. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012069.pub2. PMC 6494554. PMID 29744873.

Our findings suggest that methylphenidate may be associated with a number of serious adverse events as well as a large number of non-serious adverse events in children. Concerning adverse events associated with the treatment, our systematic review of randomised clinical trials (RCTs) demonstrated no increase in serious adverse events, but a high proportion of participants suffered a range of non-serious adverse events.

- ^ a b c d Heedes G, Ailakis J. "Methylphenidate hydrochloride (PIM 344)". INCHEM. International Programme on Chemical Safety. Archived from the original on 23 June 2015. Retrieved 23 June 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f Spiller HA, Hays HL, Aleguas A (July 2013). "Overdose of drugs for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: clinical presentation, mechanisms of toxicity, and management". CNS Drugs. 27 (7): 531–543. doi:10.1007/s40263-013-0084-8. PMID 23757186. S2CID 40931380.

The management of amphetamine, dextroamphetamine, and methylphenidate overdose is largely supportive, with a focus on interruption of the sympathomimetic syndrome with judicious use of benzodiazepines. In cases where agitation, delirium, and movement disorders are unresponsive to benzodiazepines, second-line therapies include antipsychotics such as ziprasidone or haloperidol, central alpha-adrenoreceptor agonists such as dexmedetomidine, or propofol. ... However, fatalities are rare with appropriate care

- ^ a b Bruggisser M, Bodmer M, Liechti ME (2011). "Severe toxicity due to injected but not oral or nasal abuse of methylphenidate tablets". Swiss Medical Weekly. 141: w13267. doi:10.4414/smw.2011.13267. PMID 21984207.

- ^ Nestler EJ, Barrot M, Self DW (September 2001). "DeltaFosB: a sustained molecular switch for addiction". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 98 (20): 11042–11046. Bibcode:2001PNAS...9811042N. doi:10.1073/pnas.191352698. PMC 58680. PMID 11572966.

Although the ΔFosB signal is relatively long-lived, it is not permanent. ΔFosB degrades gradually and can no longer be detected in brain after 1–2 months of drug withdrawal ... Indeed, ΔFosB is the longest-lived adaptation known to occur in adult brain, not only in response to drugs of abuse, but to any other perturbation (that does not involve lesions) as well.

- ^ Nestler EJ (December 2012). "Transcriptional mechanisms of drug addiction". Clinical Psychopharmacology and Neuroscience. 10 (3): 136–143. doi:10.9758/cpn.2012.10.3.136. PMC 3569166. PMID 23430970.

The 35–37 kD ΔFosB isoforms accumulate with chronic drug exposure due to their extraordinarily long half-lives. ... As a result of its stability, the ΔFosB protein persists in neurons for at least several weeks after cessation of drug exposure. ... ΔFosB overexpression in nucleus accumbens induces NFκB

- ^ Morton WA, Stockton GG (October 2000). "Methylphenidate Abuse and Psychiatric Side Effects". Primary Care Companion to the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2 (5): 159–164. doi:10.4088/PCC.v02n0502. PMC 181133. PMID 15014637.

- ^ a b c d e Malenka RC, Nestler EJ, Hyman SE (2009). "Chapter 15: Reinforcement and Addictive Disorders". In Sydor A, Brown RY (eds.). Molecular Neuropharmacology: A Foundation for Clinical Neuroscience (2nd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. p. 368. ISBN 9780071481274.

Cocaine, [amphetamine], and methamphetamine are the major psychostimulants of abuse. The related drug methylphenidate is also abused, although it is far less potent. These drugs elicit similar initial subjective effects ; differences generally reflect the route of administration and other pharmacokinetic factors. Such agents also have important therapeutic uses; cocaine, for example, is used as a local anesthetic (Chapter 2), and amphetamines and methylphenidate are used in low doses to treat attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and in higher doses to treat narcolepsy (Chapter 12). Despite their clinical uses, these drugs are strongly reinforcing, and their long-term use at high doses is linked with potential addiction, especially when they are rapidly administered or when high-potency forms are given.

- ^ a b Steiner H, Van Waes V (January 2013). "Addiction-related gene regulation: risks of exposure to cognitive enhancers vs. other psychostimulants". Progress in Neurobiology. 100: 60–80. doi:10.1016/j.pneurobio.2012.10.001. PMC 3525776. PMID 23085425.

- ^ Auger RR, Goodman SH, Silber MH, Krahn LE, Pankratz VS, Slocumb NL (June 2005). "Risks of high-dose stimulants in the treatment of disorders of excessive somnolence: a case-control study". Sleep. 28 (6): 667–672. doi:10.1093/sleep/28.6.667. PMID 16477952.

- ^ a b c d e f Kim Y, Teylan MA, Baron M, Sands A, Nairn AC, Greengard P (February 2009). "Methylphenidate-induced dendritic spine formation and DeltaFosB expression in nucleus accumbens". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 106 (8): 2915–2920. Bibcode:2009PNAS..106.2915K. doi:10.1073/pnas.0813179106. PMC 2650365. PMID 19202072.

Despite decades of clinical use of methylphenidate for ADHD, concerns have been raised that long-term treatment of children with this medication may result in subsequent drug abuse and addiction.

- ^ a b c Nestler EJ (December 2013). "Cellular basis of memory for addiction". Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience. 15 (4): 431–443. doi:10.31887/DCNS.2013.15.4/enestler. PMC 3898681. PMID 24459410.

Despite the importance of numerous psychosocial factors, at its core, drug addiction involves a biological process: the ability of repeated exposure to a drug of abuse to induce changes in a vulnerable brain that drive the compulsive seeking and taking of drugs, and loss of control over drug use, that define a state of addiction. ... A large body of literature has demonstrated that such ΔFosB induction in D1-type NAc neurons increases an animal's sensitivity to drug as well as natural rewards and promotes drug self-administration, presumably through a process of positive reinforcement ... Another ΔFosB target is cFos: as ΔFosB accumulates with repeated drug exposure it represses c-Fos and contributes to the molecular switch whereby ΔFosB is selectively induced in the chronic drug-treated state.41. ... Moreover, there is increasing evidence that, despite a range of genetic risks for addiction across the population, exposure to sufficiently high doses of a drug for long periods of time can transform someone who has relatively lower genetic loading into an addict.4

- ^ Ruffle JK (November 2014). "Molecular neurobiology of addiction: what's all the (Δ)FosB about?". The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 40 (6): 428–437. doi:10.3109/00952990.2014.933840. PMID 25083822. S2CID 19157711.

ΔFosB is an essential transcription factor implicated in the molecular and behavioral pathways of addiction following repeated drug exposure. The formation of ΔFosB in multiple brain regions, and the molecular pathway leading to the formation of AP-1 complexes is well understood. The establishment of a functional purpose for ΔFosB has allowed further determination as to some of the key aspects of its molecular cascades, involving effectors such as GluR2 (87,88), Cdk5 (93) and NFkB (100). Moreover, many of these molecular changes identified are now directly linked to the structural, physiological and behavioral changes observed following chronic drug exposure (60,95,97,102).

- ^ "Concerta- methylphenidate hydrochloride tablet, extended release". DailyMed. 1 July 2021. Archived from the original on 26 March 2017. Retrieved 26 March 2022.

- ^ Ishii M, Tatsuzawa Y, Yoshino A, Nomura S (April 2008). "Serotonin syndrome induced by augmentation of SSRI with methylphenidate". Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences. 62 (2): 246. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1819.2008.01767.x. PMID 18412855. S2CID 5659107.

- ^ Türkoğlu S (2015). "Serotonin syndrome with sertraline and methylphenidate in an adolescent". Clinical Neuropharmacology. 38 (2): 65–66. doi:10.1097/WNF.0000000000000075. PMID 25768857. S2CID 38523209.

- ^ Park YM, Jung YK (May 2010). "Manic switch and serotonin syndrome induced by augmentation of paroxetine with methylphenidate in a patient with major depression". Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology & Biological Psychiatry. 34 (4): 719–720. doi:10.1016/j.pnpbp.2010.03.016. PMID 20298736. S2CID 31984813.

- ^ Bodner RA, Lynch T, Lewis L, Kahn D (February 1995). "Serotonin syndrome". Neurology. 45 (2): 219–223. doi:10.1212/wnl.45.2.219. PMID 7854515. S2CID 35190429.

- ^ Patrick KS, González MA, Straughn AB, Markowitz JS (January 2005). "New methylphenidate formulations for the treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder". Expert Opinion on Drug Delivery. 2 (1): 121–143. doi:10.1517/17425247.2.1.121. PMID 16296740. S2CID 25026467.

- ^ a b Markowitz JS, DeVane CL, Boulton DW, Nahas Z, Risch SC, Diamond F, Patrick KS (June 2000). "Ethylphenidate formation in human subjects after the administration of a single dose of methylphenidate and ethanol". Drug Metabolism and Disposition. 28 (6): 620–624. PMID 10820132.

- ^ Markowitz JS, Logan BK, Diamond F, Patrick KS (August 1999). "Detection of the novel metabolite ethylphenidate after methylphenidate overdose with alcohol coingestion". Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 19 (4): 362–366. doi:10.1097/00004714-199908000-00013. PMID 10440465.

- ^ Patrick KS, Straughn AB, Minhinnett RR, Yeatts SD, Herrin AE, DeVane CL, et al. (March 2007). "Influence of ethanol and gender on methylphenidate pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics". Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 81 (3): 346–353. doi:10.1038/sj.clpt.6100082. PMC 3188424. PMID 17339864.

- ^ Roberts SM, DeMott RP, James RC (1997). "Adrenergic modulation of hepatotoxicity". Drug Metabolism Reviews. 29 (1–2): 329–353. doi:10.3109/03602539709037587. PMID 9187524.

- ^ a b Markowitz JS, Patrick KS (June 2008). "Differential pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of methylphenidate enantiomers: does chirality matter?". Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 28 (3 Suppl 2): S54-61. doi:10.1097/JCP.0b013e3181733560. PMID 18480678.

- ^ Schweri MM, Skolnick P, Rafferty MF, Rice KC, Janowsky AJ, Paul SM (October 1985). "[3H]Threo-(+/-)-methylphenidate binding to 3,4-dihydroxyphenylethylamine uptake sites in corpus striatum: correlation with the stimulant properties of ritalinic acid esters". Journal of Neurochemistry. 45 (4): 1062–70. doi:10.1111/j.1471-4159.1985.tb05524.x. PMID 4031878. S2CID 28720285.

- ^ Ding YS, Fowler JS, Volkow ND, Dewey SL, Wang GJ, Logan J, et al. (May 1997). "Chiral drugs: comparison of the pharmacokinetics of [11C]d-threo and L-threo-methylphenidate in the human and baboon brain". Psychopharmacology. 131 (1): 71–8. doi:10.1007/s002130050267. PMID 9181638. S2CID 26046917.

- ^ Ding YS, Gatley SJ, Thanos PK, Shea C, Garza V, Xu Y, et al. (September 2004). "Brain kinetics of methylphenidate (Ritalin) enantiomers after oral administration". Synapse. 53 (3): 168–75. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.514.7833. doi:10.1002/syn.20046. PMID 15236349. S2CID 11664668.

- ^ Davids E, Zhang K, Tarazi FI, Baldessarini RJ (February 2002). "Stereoselective effects of methylphenidate on motor hyperactivity in juvenile rats induced by neonatal 6-hydroxydopamine lesioning". Psychopharmacology. 160 (1): 92–8. doi:10.1007/s00213-001-0962-5. PMID 11862378. S2CID 8037050.

- ^ Williard RL, Middaugh LD, Zhu HJ, Patrick KS (February 2007). "Methylphenidate and its ethanol transesterification metabolite ethylphenidate: brain disposition, monoamine transporters and motor activity". Behavioural Pharmacology. 18 (1): 39–51. doi:10.1097/FBP.0b013e3280143226. PMID 17218796. S2CID 20232871.

- ^ McGough JJ, Pataki CS, Suddath R (July 2005). "Dexmethylphenidate extended-release capsules for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder". Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics. 5 (4): 437–41. doi:10.1586/14737175.5.4.437. PMID 16026226. S2CID 6561452.

- ^ Silva R, Tilker HA, Cecil JT, Kowalik S, Khetani V, Faleck H, Patin J (2004). "Open-label study of dexmethylphenidate hydrochloride in children and adolescents with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder". Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology. 14 (4): 555–63. doi:10.1089/cap.2004.14.555. PMID 15662147.

- ^ Arnold LE, Lindsay RL, Conners CK, Wigal SB, Levine AJ, Johnson DE, et al. (Winter 2004). "A double-blind, placebo-controlled withdrawal trial of dexmethylphenidate hydrochloride in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder". Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology. 14 (4): 542–54. doi:10.1089/cap.2004.14.542. PMID 15662146.

- ^ Spencer TJ, Adler LA, McGough JJ, Muniz R, Jiang H, Pestreich L (June 2007). "Efficacy and safety of dexmethylphenidate extended-release capsules in adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder". Biological Psychiatry. 61 (12): 1380–7. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.07.032. PMID 17137560. S2CID 45976373.

- ^ Teo SK, Scheffler MR, Wu A, Stirling DI, Thomas SD, Stypinski D, Khetani VD (February 2004). "A single-dose, two-way crossover, bioequivalence study of dexmethylphenidate HCl with and without food in healthy subjects". Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 44 (2): 173–8. doi:10.1177/0091270003261899. PMID 14747426. S2CID 20694072.

외부 링크

- "Dexmethylphenidate". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- "Dexmethylphenidate hydrochloride". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine.