사스-CoV-2

SARS-CoV-2| 중증급성호흡기증후군 코로나바이러스2 | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||

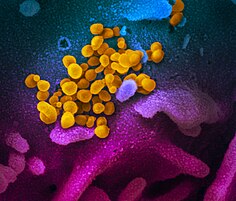

| 관상동맥이 보이는 SARS-CoV-2 바이러스 이온의 컬러 투과 전자 현미경 | |||||||||||

| |||||||||||

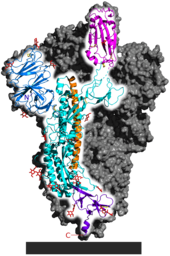

SARS-CoV-2 바이러스온의 외부 구조의 원자 모델.각각의 "공"은 [1]원자입니다.

| |||||||||||

| 바이러스 분류 | |||||||||||

| (순위 미지정): | 바이러스 | ||||||||||

| 영역: | 리보비리아 | ||||||||||

| 왕국: | 오르토나비라과 | ||||||||||

| 문: | 피수비리코타 | ||||||||||

| 클래스: | 피소니비리세테스 | ||||||||||

| 주문: | 니도비랄레스 | ||||||||||

| 패밀리: | 코로나바이러스과 | ||||||||||

| 속: | 베타코로나바이러스 | ||||||||||

| 하위 속: | 사르베코바이러스 | ||||||||||

| 종류: | |||||||||||

| 바이러스: | 중증급성호흡기증후군 코로나바이러스2 | ||||||||||

| 주목할 만한 변종 | |||||||||||

| 동의어 | |||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| 의 시리즈의 일부 |

| COVID-19 대유행 |

|---|

|

| |

중증 급성 호흡기 증후군 코로나바이러스 2(SARS-CoV-2)[2]는 진행 중인 COVID-19 [3]대유행의 원인이 되는 호흡기 질환인 COVID-19(코로나바이러스 질환 2019)를 일으키는 코로나 바이러스의 일종이다.이 바이러스는 이전에 2019년 신규 코로나 바이러스(2019-nCoV)[4][5][6][7]라는 가명을 가지고 있었으며, 인간 코로나 바이러스 2019(HCoV-19 또는 hCoV-19)[8][9][10][11]로도 불렸다.중국 후베이(湖北)성 우한(武漢)[12][13]시에서 처음 확인된 세계보건기구(WHO)는 2020년 1월 30일 국제공중보건 비상사태, 2020년 3월 11일 대유행을 선포했다.사스-CoV-2는 사람에게 [15]전염되는 양성 단일가닥 RNA[14] 바이러스이다.

사스-CoV-2는 중증급성호흡기증후군 관련 코로나바이러스(SARSR-CoV)의 바이러스로 2002-2004년 사스 발병을 [2][16]일으킨 사스-CoV-1 바이러스와 관련이 있다.이용 가능한 증거는 이것이 동물성 기원이며 박쥐가 매개하는 [17]바이러스에서 나왔다는 것을 암시하는 박쥐 코로나 바이러스와 유전적 유사성을 가지고 있다는 것을 보여준다.SARS-CoV-2가 박쥐로부터 직접 발생했는지 아니면 중간 [18]숙주를 통해 간접적으로 발생했는지에 대한 연구는 진행 중이다.이 바이러스는 유전적 다양성을 거의 보이지 않아 인간에게 사스-CoV-2를 도입한 유출 사건이 2019년 [19]말에 일어났을 가능성이 높다는 것을 보여준다.

역학 연구는 2019년 12월 - 2020년 9월에 지역사회 구성원이 면역이 없고 예방 조치가 [20]취해지지 않았을 때 각 감염이 평균 2.4 - 3.4의 새로운 감염을 일으킨 것으로 추정한다.그러나 일부 후속 변종들은 더 전염성이 [21]강해졌다.이 바이러스는 주로 기침이나 [22][23]재채기에서 생기는 것뿐만 아니라 말하거나 호흡할 때 내뿜는 에어로졸과 호흡 방울을 통해 사람들 사이에 퍼진다.그것은 레닌-안지오텐신 [24][25]시스템을 조절하는 막 단백질인 안지오텐신 변환 효소 2(ACE2)와 결합함으로써 인간의 세포로 들어간다.

용어.

중국 우한에서 처음 발병했을 때, 다양한 바이러스 이름이 사용되었고, 다른 출처에서 사용된 이름 중 일부는 "코로나 바이러스" 또는 "우한 코로나 바이러스"[26][27]를 포함했다.2020년 1월 세계보건기구(WHO)는 바이러스의 임시 명칭으로 '2019년 신종 코로나바이러스'(2019-nCoV)[5][28]를 권고했다.이는 WHO가 2015년[29] 발표한 지리적 위치, 동물 종, 질병 및 바이러스 이름으로 [30][31]사람 그룹을 사용하는 것에 대한 지침을 따른 것이다.

2020년 2월 11일, 국제 바이러스 분류 위원회는 "심각한 급성 호흡기 증후군 코로나 바이러스 2"(SARS-CoV-2)[32]라는 공식 명칭을 채택했다.사스와의 혼동을 피하기 위해 세계보건기구는 공중 보건[33][34] 통신에서 사스-CoV-2를 "COVID-19 바이러스"라고 부르기도 하고 HCoV-19라는 이름도 일부 연구 [8][9][10]기사에 포함되기도 했다.COVID-19를 "우한 바이러스"라고 지칭하는 것은 WHO 관계자들에 의해 위험하다고, 그리고 버클리 캘리포니아 대학의 아시아계 미국인학 강사 [35][36][37]하비 동에 의해 외국인 혐오증이라고 묘사되어 왔다.

감염 및 전염

사스-CoV-2의 인간 대 인간 전염은 COVID-19 [15][38][39][40]대유행 기간인 2020년 1월 20일에 확인되었다.전염은 처음에는 약 1.8m(6ft)[41][42] 범위 내에서 기침과 재채기로 인한 호흡기 방울을 통해 주로 발생하는 것으로 가정했다.레이저 광산란 실험에 따르면 말하는 것은 추가적인 전송[43][44] 방식이며 공기 [46][47]흐름이 거의 없는 실내에서 멀리까지[45] 도달하는 방식입니다.다른 연구들은 에어로졸이 잠재적으로 바이러스를 [48][49][50]전염시킬 수 있는 것과 함께 바이러스가 공기 중에 있을 수도 있다는 것을 시사했다.사람에서 사람으로 전염되는 동안, 200에서 800개의 전염성 사스-CoV-2 바이러스들이 새로운 [51][52][53]감염을 일으키는 것으로 생각됩니다.확인될 경우, 에어로졸 전송은 생체 안전성에 영향을 미칩니다. 왜냐하면 실험실에서 새로운 바이러스로 작업하는 위험과 관련된 주요 우려 사항은 다양한 실험실 활동에서 에어로졸 생성이며, 이는 즉시 인식할 수 없으며 다른 [54]과학자에게 영향을 미칠 수 있기 때문입니다.오염된 표면을 통한 간접 접촉도 [55]감염의 또 다른 가능한 원인입니다.예비 조사 결과, 바이러스는 플라스틱(폴리프로필렌) 및 스테인리스강(AISI 304)에서는 최대 3일간 생존할 수 있지만, 골판지에서는 하루 이상, 구리에서는 4시간 [10]이상 생존할 수 없는 것으로 나타났습니다.그 바이러스는 비누에 의해 비활성화되어 지질 이중층을 [56][57]불안정하게 만든다.바이러스 RNA는 감염된 [58][59]사람의 대변 샘플과 정액에서도 발견되었다.

잠복기에 바이러스가 감염되는 정도는 확실하지 않지만, 인두는 감염 후 약[60][61] 4일 후 또는 증상 발생 첫 주에 최고 바이러스 부하에 도달하여 그 [62]후 감소하는 것으로 연구 결과 나타났다.SARS-CoV-2 RNA 배출 기간은 일반적으로 증상 [63]발생 후 3일에서 46일 사이이다.

노스캐롤라이나 대학 연구팀에 의한 연구는 비강이 겉으로 보기에 주요 감염부위이며 후속 흡인 매개 바이러스가 SARS-CoV-2 병인성 [64]폐로 옮겨진다는 것을 발견했다.그들은 섬모세포와 기도와 치조영역에서 [64]각각 2형 기흉세포와 원위부 폐상피 배양에서 높은 근위부에서 낮은 근위부에서 낮은 근위부로의 감염 구배가 있다는 것을 발견했다.

연구는 고양이, 족제비, 햄스터, 비인간 영장류, 밍크, 나무쥐, 너구리, 과일박쥐, 토끼와 같은 SARS-CoV-2 [65][66][67]감염에 취약하고 내성이 있는 다양한 동물들을 확인했다.일부 기관들은 사스-CoV-2에 감염된 사람들은 [68][69]동물과의 접촉을 제한한다고 권고했다.

무증상 및 전증상 전염

2020년 2월 1일, 세계보건기구(WHO)는 "증상 없는 사례로부터의 전염은 전염의 주요 동인이 아닐 것"[70]이라고 밝혔다.한 메타분석에 따르면 감염의 17%가 무증상이며, 무증상 개인은 [71]바이러스를 전염시킬 확률이 42% 낮았다.

그러나, 중국에서 발병 초기 역학 모델은 "증상 전폐가 문서화된 감염 중 전형적일 수 있다"고 제안했고, 대다수의 [72]감염의 원인이었을 수 있다.몬테비데오에 정박했던 유람선에 탑승한 217명 중 바이러스 RNA 양성반응을 보인 128명 중 24명만이 증상을 [73]보인 것은 이 때문이다.마찬가지로, 2020년 1월과 2월에 입원한 94명의 환자를 대상으로 한 연구에서는 증상이 나타나기 2~3일 전부터 바이러스 감염이 시작되었으며, "상당수의 전염은 지수 [74]사례에서 첫 증상 이전에 발생했을 것"이라고 밝혔다.저자들은 나중에 증상이 [75]나타나기 4, 5일 전에 털갈이가 처음 추정된 것보다 일찍 시작되었다는 것을 보여주는 수정 내용을 발표했다.

재감염

재감염과 장기면역에 [76]대한 불확실성이 있다.재감염이 얼마나 일반적인지는 알려지지 않았지만 보고서에 따르면 재감염이 다양한 [76]심각도로 발생하고 있습니다.

첫 번째 재감염 사례는 홍콩에서 온 33세 남성으로, 2020년 3월 26일 첫 양성반응을 보였고, 두 번의 음성반응을 거쳐 4월 15일 퇴원했으며, 2020년 8월 15일(142일 후) 다시 양성반응을 보였으며, 이는 두 사건 사이의 바이러스 게놈이 d에 속하는 것으로 확인되었습니다.균열이 있습니다.[77]이번 연구결과는 재감염이 드물지 않은 경우 집단 면역이 바이러스를 제거하지 못할 수 있으며 백신이 [77]바이러스에 대한 평생 보호를 제공하지 못할 수 있다는 것을 시사했다.

또 다른 사례 연구에서는 2020년 4월 18일과 6월 5일에 사스-CoV-2 양성 반응을 보인 네바다 주 출신의 25세 남성이 묘사되었다(2개의 음성 테스트로 분리).게놈 분석에서 두 날짜에 표본 추출한 SARS-CoV-2 변종 간의 유의한 유전적 차이가 나타났기 때문에 사례 연구 저자는 이것이 재감염이라고 [78]판단했다.남자의 두 번째 감염은 첫 번째 감염보다 증상적으로 더 심각했지만, 이것을 설명할 수 있는 메커니즘은 [78]알려지지 않았다.

저수지 및 원점

인간을 감염시키는 병원체로 SARS-CoV-2가 등장하기 전에는 SARS-CoV-1과 MERS-CoV에 [17]의한 두 가지 동물성 코노라 바이러스 전염병이 있었다.

SARS-CoV-2에 의한 첫 번째 알려진 감염은 중국 [79]우한에서 발견되었다.바이러스가 인간에게 전염되는 원천은 불분명하며,[9][19][80] 바이러스가 확산되기 전이나 후에 병원성이 되었는지도 불분명하다.초기 감염자 중 상당수가 화난 수산물 시장 [81][82]근로자들이었기 때문에 바이러스가 시장에서 [9][83]유래한 것일 수도 있다는 주장이 제기돼 왔다.그러나 다른 연구에 따르면 방문자들이 이 바이러스를 시장에 소개했을 가능성이 있으며,[19][84] 이는 감염의 빠른 확대를 촉진시켰다.2021년 3월 세계보건기구(WHO)가 발표한 보고서에 따르면 중간 동물 숙주를 통한 인간 유출이 가장 유력한 설명이며, 박쥐로부터의 직접적인 유출이 그 다음일 가능성이 높다.식품 공급망과 화난 수산물 시장을 통한 도입도 가능하지만 가능성이 낮은 [85]또 다른 설명으로 여겨졌다.그러나 2021년 11월 한 분석에서는 가장 이른 것으로 알려진 사례가 잘못 확인되었으며, 화난시장과 관련된 초기 사례가 우세하다는 것이 [86]그 원인이라는 주장이었다.

최근 이종간 전파를 통해 감염된 바이러스는 빠른 진화가 예상된다.[87]초기 SARS-CoV-2 사례에서 추정된 돌연변이율은 사이트당 연간 [85]6.54×10이었다−4.코로나바이러스는 일반적으로 높은 유전적 [88]가소성을 가지고 있지만, SARS-CoV-2의 바이러스 진화는 복제 [89]기계의 RNA 교정 능력으로 인해 느려진다.비교를 위해 SARS-CoV-2의 생체내 바이러스 돌연변이율은 [90]인플루엔자보다 낮은 것으로 나타났다.

2002-2004년 사스(SARS중증급성호흡기증후군) 발병을 일으킨 바이러스의 천연 저장고에 대한 연구는 많은 사스 유사 박쥐 코로나바이러스를 발견하는 결과를 낳았으며, 대부분은 관박쥐에서 비롯되었다.2022년 2월 네이처(저널)에 발표된 가장 근접한 매치는 [91][92][93]라오스 푸앙의 박쥐 3종에서 수집된 바이러스 BANAL-52(사스-CoV-2와 96.8% 유사)와 BANAL-103 및 BANAL-236이었다.2020년 2월에 발행된 이전 자료에서는 중국 윈난성 모장의 박쥐에서 수집된 RaTG13 바이러스가 96.1% [79][94]유사성으로 SARS-CoV-2에 가장 가까운 것으로 확인되었다.위의 어느 것도 그것의 직계 [95]조상은 아니다.

박쥐는 사스-CoV-2의 [85][96]가장 가능성이 높은 천연 저장소로 여겨진다.박쥐 코로나 바이러스와 사스-CoV-2의 차이는 인간이 중간 [83]숙주를 통해 감염되었을 수 있다는 것을 시사하지만, 인간에게 유입되는 원인은 [97][98]아직 알려지지 않았다.

처음에는 중간 숙주로서의 팡골린의 역할이 가정되었지만(2020년 7월에 발표된 연구에 따르면 팡골린은 SARS-CoV-2 유사 코로나[99][100] 바이러스의 중간 숙주이지만), 후속 연구는 확산에 [85]대한 이들의 기여를 입증하지 못했다.이 가설에 반대하는 증거는 팡골린 바이러스 샘플이 SARS-CoV-2와 너무 멀리 떨어져 있다는 사실을 포함한다: 광둥에서 포착된 팡골린으로부터 얻은 분리체는 사스-CoV-2 게놈과 순서상 92%만 동일했다(90% 이상의 매칭은 높게 들릴 수 있지만 게놈 측면에서는 매우 큰 진화적[101] 격차이다).또한, 몇 가지 중요한 [102]아미노산의 유사성에도 불구하고, 팡골린 바이러스 샘플은 인간의 ACE2 [103]수용체에 대한 결합성이 낮다.

계통학 및 분류학

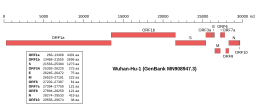

SARS-CoV-2의 가장 초기 염기서열 샘플인 격리 우한-후-1의 게놈 조직 | |

| NCBI 게놈 ID | 86693 |

|---|---|

| 게놈 크기 | 29,903 베이스 |

| 완료년도 | 2020 |

| 게놈 브라우저(UCSC) | |

SARS-CoV-2는 코로나바이러스로 [27]알려진 광범위한 바이러스군에 속합니다.단일 선형 RNA 세그먼트를 가진 양성 감지 단일 가닥 RNA(+ssRNA) 바이러스입니다.코로나바이러스는 인간, 가축과 반려동물을 포함한 다른 포유류, 조류 종을 [104]감염시킨다.인간 코로나바이러스는 일반적인 감기부터 중동호흡기증후군과 같은 더 심각한 질병까지 다양한 질병을 일으킬 수 있다.SARS-CoV-2는 229E, NL63, OC43, HKU1, MERS-CoV,[105] 그리고 원래의 SARS-CoV에 이어 사람들을 감염시키는 것으로 알려진 7번째 코로나 바이러스이다.

2003년 사스(SARS·사스) 발생과 관련된 코로나 바이러스와 마찬가지로 사스-CoV-2는 사르베코바이러스 아속(베타-CoV 계통 B)[106][107]에 속한다.코로나바이러스는 자주 [108]재조합된다.SARS-CoV-2와 같은 분할되지 않은 RNA 바이러스의 재조합 메커니즘은 일반적으로 복제 [109]중에 유전자 물질이 한 RNA 템플릿 분자에서 다른 RNA로 전환되는 복제에 의한 것이다.SARS-CoV-2 RNA 배열은 길이가 [110]약 30,000개이며, 코로나 바이러스 치고는 비교적 길다(모든 RNA [111]계열 중 가장 큰 게놈을 가지고 있다).그것의 게놈은 거의 전적으로 다른 코로나 바이러스와 [108]공유되는 특성인 단백질 코드 배열로 구성되어 있다.

SARS-CoV-2의 특징 중 하나는 [102]퓨린에 의해 절단된 다염기 부위의 통합으로, 퓨린의 [112]독성을 높이는 중요한 요소로 보인다.SARS-CoV-2 S 단백질의 퓨린 클리비지 부위의 획득은 [113]인간에 대한 동물성 전달에 필수적이라고 제안되었다.푸린단백질가수분해효소는 분해부위가 아래쪽 화살표로 표시되고 X가 아미노산인 [114][115]표준펩타이드 배열 RX[R/K] R↓X를 인식한다.SARS-CoV-2에서 인식 부위는 아미노산 배열 PRA에 [116]대응하는 12코돈 뉴클레오티드 배열 CCT CGG CGG GCA에 의해 형성된다.이 배열은 스파이크 [117]단백질의 S1/S2 절단 부위(P RR A R↓S)를 형성하는 아르기닌 및 세린의 상류이다.이러한 부위는 Orthocoronavirinae [116]내의 다른 바이러스에서 자연적으로 발생하는 일반적인 특징이지만, 베타-CoV속의 [118]다른 바이러스에서는 거의 나타나지 않으며, 이러한 [102]부위의 하위 속에서는 특이하다.퓨린 절단 부위 PRRAR↓는 알파코로나바이러스 [119]1주인 고양이 코로나 바이러스와 동일하다.

바이러스 유전자 배열 데이터는 시간과 공간에 의해 분리된 바이러스가 역학적으로 [120]연관될 가능성이 있는지에 대한 중요한 정보를 제공할 수 있다.충분한 수의 염기서열 게놈이 있으면 바이러스군의 돌연변이 이력의 계통수를 재구성할 수 있다.2020년 1월 12일까지 5개의 사스-CoV-2 게놈이 우한에서 분리되고 중국 질병통제예방센터(CCDC)와 기타 [110][121]기관에 의해 보고되었으며, 2020년 [122]1월 30일까지 게놈 수는 42개로 증가했다.이들 샘플의 계통학적 분석 결과, "공통 조상에 비해 최대 7개의 돌연변이와 높은 관련이 있다"는 결과가 나왔으며, 이는 첫 [122]번째 인체 감염이 2019년 11월 또는 12월에 발생했음을 의미한다.대유행 초기 계통수 토폴로지를 검사한 결과 인간 분리주 [123]간에 높은 유사성이 발견되었다.2021년 [update]8월 21일 현재, 남극 대륙을 제외한 모든 대륙에서 표본 추출된 19개 변종에 속하는 3,422개의 SARS-CoV-2 게놈이 [124]공개되었다.

2020년 2월 11일, 국제 바이러스 분류 위원회는 보존된 핵산의 5개 염기서열을 기반으로 코로나 바이러스 간의 위계관계를 계산하는 기존 규칙에 따르면, 당시 2019-nCoV라고 불렸던 것과 2003년 사스 발생에서 발생한 바이러스 사이의 차이는 만들기 불충분하다고 발표했다.바이러스 종을 분리하는 거죠따라서 그들은 2019-nCoV를 중증 급성 호흡기 증후군 관련 코로나 바이러스로 [125]식별했다.

2020년 7월, 과학자들은 스파이크 단백질 변종 G614를 가진 더 전염성이 높은 SARS-CoV-2 변종이 D614를 대체하여 [126][127]대유행의 지배적인 형태로 나타났다고 보고했다.

코로나 바이러스 게놈과 하위 유전자는 6개의 개방형 판독 프레임(ORF)[128]을 인코딩한다.2020년 10월, 연구원들은 사스-CoV-2 게놈에서 ORF3d라는 이름의 중복 유전자를 발견했다.ORF3d에 의해 생성된 단백질이 어떤 기능을 가지고 있는지는 알 수 없지만, 그것은 강한 면역 반응을 유발한다.ORF3d는 판골린을 [129][130]감염시키는 코로나 바이러스의 변종에서 이전에 확인되었다.

계통수

SARS-CoV-2 및 관련 코로나 바이러스의 전체 유전자 염기서열에 기초한 계통수는 다음과 같다.[131][132]

| 사스-CoV-2 관련 코로나바이러스 |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| SARS-CoV-1, 79%는 SARS-CoV-2 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

변종

사스-CoV-2에는 훨씬 더 큰 [141]집단으로 분류될 수 있는 수천 가지의 변종들이 있다.몇 가지 다른 분류군 명명법이 제안되었다.Nextstrain은 5개의 클래스(19A, 19B, 20A, 20B, 20C)로, GISAID는 7개의 클래스(19A, O, V, S, GH, GR)[142]로 나뉩니다.

2020년 말에 몇 가지 주목할 만한 SARS-CoV-2 변종이 나타났다.세계보건기구(WHO)는 현재 다음과 [143]같은 다섯 가지 우려 사항을 선언했습니다.

- 알파: 리니지 B.1.1.7은 2020년 9월 영국에서 출현하여 전염성과 독성이 증가하였다.주목할 만한 돌연변이는 N501Y와 P681H이다.

- 베타: 리니지 B.1.351은 2020년 5월 남아프리카공화국에서 출현했으며, 일부 공중 보건 관계자들은 일부 백신의 효능에 대한 영향에 대해 경종을 울렸다.주목할 만한 돌연변이는 K417N, E484K 및 N501Y이다.

- 감마: 리니지 P.1은 항원성 변화와 함께 전염성과 독성이 증가했다는 증거와 함께 2020년 11월에 브라질에서 나타났다.백신 효능에 대한 비슷한 우려가 제기되었다.주목할 만한 돌연변이로는 K417N, E484K 및 N501Y도 있다.

- 델타: 리니지 B.1.617.2는 2020년 10월에 인도에서 등장했습니다.또한 전염성이 증가하고 항원성이 변화한다는 증거가 있다.

- 오미크론: 리니지 B.1.529는 2021년 11월 보츠와나에서 등장했다.

다른 주목할 만한 변종으로는 조사 중인 6개의 다른 WHO 지정 변종과 덴마크의 밍크 사이에서 출현하여 밍크 안락사 캠페인을 사실상 [144]멸종시킨 클러스터 5가 있다.

바이러스학

구조.

각 SARS-CoV-2 비리온은 60-140나노미터(2.4×10-5−6)이다.지름이 [105][82]5×10인치−6)이며, 지구촌 인구 내 질량은 0.1~[145]10kg으로 추정되고 있다.다른 코로나 바이러스들처럼, SARS-CoV-2는 S, E, M, N으로 알려진 4개의 구조 단백질을 가지고 있다; N 단백질은 RNA 게놈을 고정시키고, S, E, 그리고 M 단백질은 함께 바이러스 [146]외피를 형성한다.코로나바이러스 S 단백질은 당단백질이며 I형 막 단백질이다.[113]2개의 기능부(S1과 S2)[104]로 구분된다.SARS-CoV-2에서 극저온 전자현미경을 [147][148]이용해 원자 수준에서 촬상된 스파이크 단백질은 바이러스가 [146]숙주세포의 막에 부착되어 융합되는 단백질이다. 구체적으로는 S1 서브유닛이 부착을 촉매하는 S2 서브유닛 [149]융합이다.

게놈

2022년 초까지 약 700만 개의 SARS-CoV-2 게놈이 배열되어 공공 데이터베이스에 저장되었고 매달 [150]80만 개 정도가 추가되었다.

SARS-CoV-2는 약 3만 염기의 [104]선형의 양성 단일 가닥 RNA 게놈을 가지고 있다.그것의 게놈은 다른 코로나 [151]바이러스들처럼 시토신(C)과 구아닌(G) 뉴클레오티드에 대한 편견을 가지고 있다.게놈은 U(32.2%), A(29.9%), G(19.6%)와 C(18.[152]3%)의 조성이 가장 높다.뉴클레오티드 편향은 구아닌과 사이토신이 각각 [153]아데노신과 우라실로 변이되면서 발생한다.CG 디뉴클레오티드의 돌연변이는 세포의 [154]아연 핑거 항바이러스 단백질 관련 방어 메커니즘을 피하고 복제 및 번역 중에 게놈을 결합 해제하는 에너지를 낮추기 위해 발생하는 것으로 생각됩니다(아데노신과 우라실 염기쌍은 2개의 수소 결합을 통해, 시토신과 구아닌은 3개를 통해).[153]게놈에서 CG 디뉴클레오티드의 고갈은 바이러스를 현저한 코돈 사용 편중으로 이끌었다.예를 들어 Arginine의 6가지 코돈은 AGA(2.67, CGU(1.46, AGG(.81, CGC 0.58, CGA.29 및 CGG(.19)[152]의 상대적인 동의어 코돈 사용을 가지고 있습니다.유사한 코돈 사용 편향 경향은 다른 사스 관련 코로나 [155]바이러스에서도 나타난다.

레플리케이션 사이클

바이러스 감염은 바이러스 입자가 숙주 표면 세포 [156]수용체에 결합하면서 시작된다.바이러스의 스파이크 단백질에 대한 단백질 모델링 실험은 곧 SARS-CoV-2가 세포 [157]진입 메커니즘으로 사용하기 위해 인간 세포의 수용체 안지오텐신 변환 효소 2(ACE2)에 충분한 친화력을 가지고 있다는 것을 시사했다.2020년 1월 22일까지 중국의 한 그룹과 미국의 한 그룹이 독립적으로 역유전학적 방법을 사용하여 ACE2가 SARS-CoV-2의 [79][158][159][160]수용체 역할을 할 수 있음을 실험적으로 입증했다.연구에 따르면 사스-CoV-2는 원래 사스 [147][161]바이러스보다 인간의 ACE2에 더 높은 친화력을 가지고 있다.사스-CoV-2는 또한 세포 [162]진입을 돕기 위해 바시진을 사용할 수 있다.

SARS-CoV-2의 [24]진입에는 막간 통과 단백질 효소인 세린2(TMPRSS2)에 의한 초기 스파이크 단백질 프라이밍이 필수적이다.호스트 단백질 neuroilin 1(NRP1)은 ACE2를 [163]사용하여 호스트 세포 진입 시 바이러스를 지원할 수 있습니다.SARS-CoV-2 비리온이 표적 세포에 부착된 후 세포의 TMPRSS2가 바이러스의 스파이크 단백질을 절단하여 S2 서브유닛의 융합펩타이드와 숙주 [149]수용체 ACE2를 노출시킨다.핵융합 후, 바이러스온 주위에 내분체가 형성되어 숙주 세포의 나머지 부분으로부터 분리된다.비리온은 엔도솜의 pH가 떨어지거나 숙주 시스테인 단백질 분해효소인 카테프신이 [149]엔도솜을 분해할 때 빠져나간다.그리고 나서 바이러스리온은 RNA를 세포에 방출하고 세포가 더 많은 [164]세포를 감염시키는 바이러스의 복사본을 만들고 퍼뜨리도록 강요한다.

사스-CoV-2는 숙주 세포에서 새로운 바이러스들의 분해를 촉진하고 면역 [146]반응을 억제하는 최소 세 가지 독성 인자를 생성한다.유사한 코로나바이러스에서 볼 수 있듯이 ACE2의 하향 조절을 포함하는지 여부는 조사 중에 있다(2020년 [165]5월 현재).

치료 및 약물 개발

사스-CoV-2를 효과적으로 억제하는 약은 거의 없는 것으로 알려져 있다.마시티닙은 임상적으로 안전한 약물로 최근 주요 단백질 분해효소인 3CLpro를 억제하는 것으로 밝혀졌으며 생쥐의 폐와 코에서 바이러스성 티터가 200배 이상 감소하는 것으로 나타났다.그러나 2021년 [166][needs update]8월 현재 인체에서 COVID-19 치료를 위해 승인되지 않았다.2021년 12월 미국은 바이러스 치료를 위해 Nirmatrelvir/Ritonavir에 긴급 사용을 허가했고,[168][169][170] 유럽연합, 영국 및 캐나다도 [167]곧 완전한 허가를 받았다.한 연구에 따르면 Nirmatrelvir/Ritonavir는 입원 및 사망 위험을 88%[171] 줄였다.

COVID Moonshot은 SARS-CoV-2 [172]치료를 위한 특허가 없는 경구 항바이러스제 개발을 목표로 2020년 3월에 시작된 국제 공동 오픈 과학 프로젝트이다.

역학

중국 감시 시스템 내에서 수집된 소급 테스트에서는 2019년 [85]후반기에 우한에서 SARS-CoV-2의 실질적인 인식되지 않은 순환 징후가 발견되지 않았다.

2020년 11월 메타분석에서는 바이러스의 기본 번식수( 0 를 2.39~3.[20]44로 추정했다.이것은 지역사회의 구성원이 면역이 되지 않고 예방 조치가 취해지지 않을 때 바이러스에 의한 각각의 감염이 2.39에서 3.44의 새로운 감염을 야기할 것으로 예상된다는 것을 의미한다.유람선에서 [173]볼 수 있는 것과 같이 인구 밀도가 높은 조건에서는 복제 수가 더 높을 수 있다.인간의 행동은 R0의 값에 영향을 미치므로 R0의 추정치는 다른 국가, 문화 및 사회 규범에 따라 다르다.예를 들어, 한 연구에서는 스웨덴, 벨기에, 네덜란드에서 상대적으로 낮은 R0(약 3.5)을 발견한 반면, 스페인과 미국은 R0 값(각각 5.9 [174]- 6.4)이 유의미하게 높았다.

| 변종 | R0 | 원천 |

|---|---|---|

| 기준/추골 변형률 | ~2.8 | [175] |

| 알파(B.1.1.7) | (이전 모델보다 40~90% 높음) | [176] |

| 델타(B.1.617.2) | ~5 (3-8) | [177] |

중국 [178]본토에서 확인된 감염 사례는 약 96,000건이다.확인된 사례나 진단 가능한 질병으로 진행되는 감염의 비율은 [179]아직 불분명하지만, 한 수학적 모델은 2020년 1월 25일 우한에서만 75,815명이 감염되었다고 추정했다.이 때 전 세계적으로 확인된 환자 수는 2,015명에 [180]불과했다.2020년 2월 24일 이전에는 전 세계 COVID-19로 인한 사망자의 95% 이상이 우한이 [181][182]위치한 후베이성에서 발생했다.2022년 7월 29일 현재, 이 비율은 0.050%[178]로 감소하였다.

2022년 7월 29일 현재 진행 중인 [178]대유행에서 확인된 SARS-CoV-2 감염 환자는 총 574,933,734명이다.바이러스로 인한 총 사망자 수는 6,395,[178]753명이다.

「 」를 참조해 주세요.

- 3C양단백질가수분해효소(NS5)

레퍼런스

- ^ Solodovnikov, Alexey; Arkhipova, Valeria (29 July 2021). "Достоверно красиво: как мы сделали 3D-модель SARS-CoV-2" [Truly beautiful: how we made the SARS-CoV-2 3D model] (in Russian). N+1. Archived from the original on 30 July 2021. Retrieved 30 July 2021.

- ^ Zimmer C (26 February 2021). "The Secret Life of a Coronavirus - An oily, 100-nanometer-wide bubble of genes has killed more than two million people and reshaped the world. Scientists don't quite know what to make of it". Archived from the original on 27 February 2021. Retrieved 28 February 2021.

- ^ Surveillance case definitions for human infection with novel coronavirus (nCoV): interim guidance v1, January 2020 (Report). World Health Organization. January 2020. hdl:10665/330376. WHO/2019-nCoV/Surveillance/v2020.1.

- ^ a b "Healthcare Professionals: Frequently Asked Questions and Answers". United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 11 February 2020. Archived from the original on 14 February 2020. Retrieved 15 February 2020.

- ^ "About Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV)". United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 11 February 2020. Archived from the original on 11 February 2020. Retrieved 25 February 2020.

- ^ Harmon A (4 March 2020). "We Spoke to Six Americans with Coronavirus". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 13 March 2020. Retrieved 16 March 2020.

- ^ a b Wong G, Bi YH, Wang QH, Chen XW, Zhang ZG, Yao YG (May 2020). "Zoonotic origins of human coronavirus 2019 (HCoV-19 / SARS-CoV-2): why is this work important?". Zoological Research. 41 (3): 213–219. doi:10.24272/j.issn.2095-8137.2020.031. PMC 7231470. PMID 32314559.

- ^ a b c d Andersen KG, Rambaut A, Lipkin WI, Holmes EC, Garry RF (April 2020). "The proximal origin of SARS-CoV-2". Nature Medicine. 26 (4): 450–452. doi:10.1038/s41591-020-0820-9. PMC 7095063. PMID 32284615.

- ^ a b c van Doremalen N, Bushmaker T, Morris DH, Holbrook MG, Gamble A, Williamson BN, et al. (April 2020). "Aerosol and Surface Stability of SARS-CoV-2 as Compared with SARS-CoV-1". The New England Journal of Medicine. 382 (16): 1564–1567. doi:10.1056/NEJMc2004973. PMC 7121658. PMID 32182409.

- ^ "hCoV-19 Database". China National GeneBank. Archived from the original on 17 June 2020. Retrieved 2 June 2020.

- ^ "Statement on the second meeting of the International Health Regulations (2005) Emergency Committee regarding the outbreak of novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV)". World Health Organization (WHO) (Press release). 30 January 2020. Archived from the original on 31 January 2020. Retrieved 30 January 2020.

- ^ "WHO Director-General's opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19 – 11 March 2020". World Health Organization (WHO) (Press release). 11 March 2020. Archived from the original on 11 March 2020. Retrieved 12 March 2020.

- ^ Machhi J, Herskovitz J, Senan AM, Dutta D, Nath B, Oleynikov MD, et al. (September 2020). "The Natural History, Pathobiology, and Clinical Manifestations of SARS-CoV-2 Infections". Journal of Neuroimmune Pharmacology. 15 (3): 359–386. doi:10.1007/s11481-020-09944-5. PMC 7373339. PMID 32696264.

- ^ a b Chan JF, Yuan S, Kok KH, To KK, Chu H, Yang J, et al. (February 2020). "A familial cluster of pneumonia associated with the 2019 novel coronavirus indicating person-to-person transmission: a study of a family cluster". Lancet. 395 (10223): 514–523. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30154-9. PMC 7159286. PMID 31986261.

- ^ "New coronavirus stable for hours on surfaces". National Institutes of Health (NIH). NIH.gov. 17 March 2020. Archived from the original on 23 March 2020. Retrieved 4 May 2020.

- ^ a b V'kovski P, Kratzel A, Steiner S, Stalder H, Thiel V (March 2021). "Coronavirus biology and replication: implications for SARS-CoV-2". Nat Rev Microbiol (Review). 19 (3): 155–170. doi:10.1038/s41579-020-00468-6. PMC 7592455. PMID 33116300.

- ^ Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV): situation report, 22 (Report). World Health Organization. 11 February 2020. hdl:10665/330991.

- ^ a b c Cohen J (January 2020). "Wuhan seafood market may not be source of novel virus spreading globally". Science. doi:10.1126/science.abb0611. S2CID 214574620.

- ^ a b Billah MA, Miah MM, Khan MN (11 November 2020). "Reproductive number of coronavirus: A systematic review and meta-analysis based on global level evidence". PLOS ONE. 15 (11): e0242128. Bibcode:2020PLoSO..1542128B. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0242128. PMC 7657547. PMID 33175914.

- ^ "COVID-19 variants: What's the concern?". Mayo Clinic.

- ^ 2020년 4월 3일 웨이백 머신에서 코로나바이러스가 퍼지는 방법, 질병통제예방센터, 2021년 5월 14일 회수.

- ^ 코로나바이러스병(COVID-19): 어떻게 전염되죠?2020년 10월 15일 WHO Wayback Machine에 보관"

- ^ a b Hoffmann M, Kleine-Weber H, Schroeder S, Krüger N, Herrler T, Erichsen S, et al. (April 2020). "SARS-CoV-2 Cell Entry Depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and Is Blocked by a Clinically Proven Protease Inhibitor". Cell. 181 (2): 271–280.e8. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2020.02.052. PMC 7102627. PMID 32142651.

- ^ Zhao P, Praissman JL, Grant OC, Cai Y, Xiao T, Rosenbalm KE, et al. (October 2020). "Virus-Receptor Interactions of Glycosylated SARS-CoV-2 Spike and Human ACE2 Receptor". Cell Host & Microbe. 28 (4): 586–601.e6. doi:10.1016/j.chom.2020.08.004. PMC 7443692. PMID 32841605.

- ^ Huang P (22 January 2020). "How Does Wuhan Coronavirus Compare with MERS, SARS and the Common Cold?". NPR. Archived from the original on 2 February 2020. Retrieved 3 February 2020.

- ^ a b Fox D (January 2020). "What you need to know about the novel coronavirus". Nature. doi:10.1038/d41586-020-00209-y. PMID 33483684. S2CID 213064026.

- ^ World Health Organization (30 January 2020). Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV): situation report, 10 (Report). World Health Organization. hdl:10665/330775.

- ^ "World Health Organization Best Practices for the Naming of New Human Infectious Diseases" (PDF). WHO. May 2015. Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 February 2020.

- ^ "Novel coronavirus named 'Covid-19': WHO". TODAYonline. Archived from the original on 21 March 2020. Retrieved 11 February 2020.

- ^ "The coronavirus spreads racism against—and among—ethnic Chinese". The Economist. 17 February 2020. Archived from the original on 17 February 2020. Retrieved 17 February 2020.

- ^ "Naming the coronavirus disease (COVID-2019) and the virus that causes it". World Health Organization. Archived from the original on 28 February 2020. Retrieved 14 December 2020.

ICTV announced "severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2)" as the name of the new virus on 11 February 2020. This name was chosen because the virus is genetically related to the coronavirus responsible for the SARS outbreak of 2003. While related, the two viruses are different.

- ^ Hui M (18 March 2020). "Why won't the WHO call the coronavirus by its name, SARS-CoV-2?". Quartz. Archived from the original on 25 March 2020. Retrieved 26 March 2020.

- ^ "Naming the coronavirus disease (COVID-2019) and the virus that causes it". World Health Organization. Archived from the original on 28 February 2020. Retrieved 14 December 2020.

From a risk communications perspective, using the name SARS can have unintended consequences in terms of creating unnecessary fear for some populations. ... For that reason and others, WHO has begun referring to the virus as "the virus responsible for COVID-19" or "the COVID-19 virus" when communicating with the public. Neither of these designations is [sic] intended as replacements for the official name of the virus as agreed by the ICTV.

- ^ 버클리 캘리포니아 대학의 아시아계 미국인학 강사 하비 동은 워싱턴 포스트에 "이는 인종차별주의이며 외국인 혐오증을 일으킨다"고 말했다."매우 위험한 상황입니다."

- ^ https://thehill.com/homenews/administration/488479-who-official-warns-against-calling-it-chinese-virus-says-there-is-no?rl=1 라이언이 이 문구에 반대하는 첫 번째 WHO 관리는 아니다.테드로스 아드하놈 게브레이수스 사무총장은 이달 초 이 용어가 "보기에 고통스럽다"며 "바이러스 자체보다 더 위험하다"고 말했다.

- ^ Gover AR, Harper SB, Langton L (July 2020). "Anti-Asian Hate Crime During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Exploring the Reproduction of Inequality". American Journal of Criminal Justice. 45 (4): 647–667. doi:10.1007/s12103-020-09545-1. PMC 7364747. PMID 32837171.

- ^ Li JY, You Z, Wang Q, Zhou ZJ, Qiu Y, Luo R, Ge XY (March 2020). "The epidemic of 2019-novel-coronavirus (2019-nCoV) pneumonia and insights for emerging infectious diseases in the future". Microbes and Infection. 22 (2): 80–85. doi:10.1016/j.micinf.2020.02.002. PMC 7079563. PMID 32087334.

- ^ Kessler G (17 April 2020). "Trump's false claim that the WHO said the coronavirus was 'not communicable'". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 17 April 2020. Retrieved 17 April 2020.

- ^ Kuo L (21 January 2020). "China confirms human-to-human transmission of coronavirus". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 22 March 2020. Retrieved 18 April 2020.

- ^ "How COVID-19 Spreads". U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 27 January 2020. Archived from the original on 28 January 2020. Retrieved 29 January 2020.

- ^ Edwards E (25 January 2020). "How does coronavirus spread?". NBC News. Archived from the original on 28 January 2020. Retrieved 13 March 2020.

- ^ Anfinrud P, Stadnytskyi V, Bax CE, Bax A (May 2020). "Visualizing Speech-Generated Oral Fluid Droplets with Laser Light Scattering". The New England Journal of Medicine. 382 (21): 2061–2063. doi:10.1056/NEJMc2007800. PMC 7179962. PMID 32294341.

- ^ Stadnytskyi V, Bax CE, Bax A, Anfinrud P (June 2020). "The airborne lifetime of small speech droplets and their potential importance in SARS-CoV-2 transmission". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 117 (22): 11875–11877. doi:10.1073/pnas.2006874117. PMC 7275719. PMID 32404416.

- ^ Klompas M, Baker MA, Rhee C (August 2020). "Airborne Transmission of SARS-CoV-2: Theoretical Considerations and Available Evidence". JAMA. 324 (5): 441–442. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.12458. PMID 32749495. S2CID 220500293.

Investigators have demonstrated that speaking and coughing produce a mixture of both droplets and aerosols in a range of sizes, that these secretions can travel together for up to 27 feet, that it is feasible for SARS-CoV-2 to remain suspended in the air and viable for hours, that SARS-CoV-2 RNA can be recovered from air samples in hospitals, and that poor ventilation prolongs the amount of time that aerosols remain airborne.

- ^ Rettner R (21 January 2021). "Talking is worse than coughing for spreading COVID-19 indoors". livescience.com. Retrieved 23 January 2021.

In one modeled scenario, the researchers found that after a short cough, the number of infectious particles in the air would quickly fall after 1 to 7 minutes; in contrast, after speaking for 30 seconds, only after 30 minutes would the number of infectious particles fall to similar levels; and a high number of particles were still suspended after one hour. In other words, a dose of virus particles capable of causing an infection would linger in the air much longer after speech than a cough. (In this modeled scenario, the same number of droplets were admitted during a 0.5-second cough as during the course of 30 seconds of speech.)

- ^ de Oliveira PM, Mesquita LC, Gkantonas S, Giusti A, Mastorakos E (January 2021). "Evolution of spray and aerosol from respiratory releases: theoretical estimates for insight on viral transmission". Proceedings of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences. 477 (2245): 20200584. Bibcode:2021RSPSA.47700584D. doi:10.1098/rspa.2020.0584. PMC 7897643. PMID 33633490. S2CID 231643585.

- ^ Mandavilli A (4 July 2020). "239 Experts With One Big Claim: The Coronavirus Is Airborne – The W.H.O. has resisted mounting evidence that viral particles floating indoors are infectious, some scientists say. The agency maintains the research is still inconclusive". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 17 November 2020. Retrieved 5 July 2020.

- ^ Tufekci Z (30 July 2020). "We Need to Talk About Ventilation". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on 17 November 2020. Retrieved 8 September 2020.

- ^ Lewis D (July 2020). "Mounting evidence suggests coronavirus is airborne - but health advice has not caught up". Nature. 583 (7817): 510–513. Bibcode:2020Natur.583..510L. doi:10.1038/d41586-020-02058-1. PMID 32647382. S2CID 220470431.

- ^ Popa A, Genger JW, Nicholson MD, Penz T, Schmid D, Aberle SW, et al. (December 2020). "Genomic epidemiology of superspreading events in Austria reveals mutational dynamics and transmission properties of SARS-CoV-2". Science Translational Medicine. 12 (573): eabe2555. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.abe2555. PMC 7857414. PMID 33229462.

- ^ He X, Lau EH, Wu P, Deng X, Wang J, Hao X, et al. (May 2020). "Temporal dynamics in viral shedding and transmissibility of COVID-19". Nature Medicine. 26 (5): 672–675. doi:10.1021/acs.chas.0c00035. PMC 7216769. PMID 32296168.

- ^ Watanabe T, Bartrand TA, Weir MH, Omura T, Haas CN (July 2010). "Development of a dose-response model for SARS coronavirus". Risk Analysis. 30 (7): 1129–38. doi:10.1111/j.1539-6924.2010.01427.x. PMC 7169223. PMID 20497390.

- ^ Artika IM, Ma'roef CN (May 2017). "Laboratory biosafety for handling emerging viruses". Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Biomedicine. 7 (5): 483–491. doi:10.1016/j.apjtb.2017.01.020. PMC 7103938. PMID 32289025.

- ^ "Getting your workplace ready for COVID-19" (PDF). World Health Organization. 27 February 2020. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 March 2020. Retrieved 3 March 2020.

- ^ Yong E (20 March 2020). "Why the Coronavirus Has Been So Successful". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on 20 March 2020. Retrieved 20 March 2020.

- ^ Gibbens S (18 March 2020). "Why soap is preferable to bleach in the fight against coronavirus". National Geographic. Archived from the original on 2 April 2020. Retrieved 2 April 2020.

- ^ Holshue ML, DeBolt C, Lindquist S, Lofy KH, Wiesman J, Bruce H, et al. (March 2020). "First Case of 2019 Novel Coronavirus in the United States". The New England Journal of Medicine. 382 (10): 929–936. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2001191. PMC 7092802. PMID 32004427.

- ^ Li D, Jin M, Bao P, Zhao W, Zhang S (May 2020). "Clinical Characteristics and Results of Semen Tests Among Men With Coronavirus Disease 2019". JAMA Network Open. 3 (5): e208292. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.8292. PMC 7206502. PMID 32379329.

- ^ Wölfel R, Corman VM, Guggemos W, Seilmaier M, Zange S, Müller MA, et al. (May 2020). "Virological assessment of hospitalized patients with COVID-2019". Nature. 581 (7809): 465–469. Bibcode:2020Natur.581..465W. doi:10.1038/s41586-020-2196-x. PMID 32235945.

- ^ Kupferschmidt K (February 2020). "Study claiming new coronavirus can be transmitted by people without symptoms was flawed". Science. doi:10.1126/science.abb1524. S2CID 214094598.

- ^ To KK, Tsang OT, Leung WS, Tam AR, Wu TC, Lung DC, et al. (May 2020). "Temporal profiles of viral load in posterior oropharyngeal saliva samples and serum antibody responses during infection by SARS-CoV-2: an observational cohort study". The Lancet. Infectious Diseases. 20 (5): 565–574. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30196-1. PMC 7158907. PMID 32213337.

- ^ Avanzato VA, Matson MJ, Seifert SN, Pryce R, Williamson BN, Anzick SL, et al. (December 2020). "Case Study: Prolonged Infectious SARS-CoV-2 Shedding from an Asymptomatic Immunocompromised Individual with Cancer". Cell. 183 (7): 1901–1912.e9. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2020.10.049. PMC 7640888. PMID 33248470.

- ^ a b Hou YJ, Okuda K, Edwards CE, Martinez DR, Asakura T, Dinnon KH, et al. (July 2020). "SARS-CoV-2 Reverse Genetics Reveals a Variable Infection Gradient in the Respiratory Tract". Cell. 182 (2): 429–446.e14. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2020.05.042. PMC 7250779. PMID 32526206.

- ^ Banerjee A, Mossman K, Baker ML (February 2021). "Zooanthroponotic potential of SARS-CoV-2 and implications of reintroduction into human populations". Cell Host & Microbe. 29 (2): 160–164. doi:10.1016/j.chom.2021.01.004. PMC 7837285. PMID 33539765.

- ^ "Questions and Answers on the COVID-19: OIE – World Organisation for Animal Health". www.oie.int. Archived from the original on 31 March 2020. Retrieved 16 April 2020.

- ^ Goldstein J (6 April 2020). "Bronx Zoo Tiger Is Sick with the Coronavirus". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 9 April 2020. Retrieved 10 April 2020.

- ^ "USDA Statement on the Confirmation of COVID-19 in a Tiger in New York". United States Department of Agriculture. 5 April 2020. Archived from the original on 15 April 2020. Retrieved 16 April 2020.

- ^ "If You Have Animals—Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19)". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 13 April 2020. Archived from the original on 1 April 2020. Retrieved 16 April 2020.

- ^ World Health Organization (1 February 2020). Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV): situation report, 12 (Report). World Health Organization. hdl:10665/330777.

- ^ Nogrady B (November 2020). "What the data say about asymptomatic COVID infections". Nature. 587 (7835): 534–535. Bibcode:2020Natur.587..534N. doi:10.1038/d41586-020-03141-3. PMID 33214725.

- ^ Li R, Pei S, Chen B, Song Y, Zhang T, Yang W, Shaman J (May 2020). "Substantial undocumented infection facilitates the rapid dissemination of novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2)". Science. 368 (6490): 489–493. Bibcode:2020Sci...368..489L. doi:10.1126/science.abb3221. PMC 7164387. PMID 32179701.

- ^ Daily Telegraph, 2020년 5월 28일 목요일, 의학 저널 Torax를 참조하는 2면 1열; Thorax 기사 COVID-19: 어니스트 섀클턴 아카이브된 2020년 5월 30일 웨이백 머신에서

- ^ He X, Lau EH, Wu P, Deng X, Wang J, Hao X, et al. (May 2020). "Temporal dynamics in viral shedding and transmissibility of COVID-19". Nature Medicine. 26 (5): 672–675. doi:10.1038/s41591-020-0869-5. PMID 32296168.

- ^ He, Xi; Lau, Eric H. Y.; Wu, Peng; Deng, Xilong; Wang, Jian; Hao, Xinxin; Lau, Yiu Chung; Wong, Jessica Y.; Guan, Yujuan; Tan, Xinghua; Mo, Xiaoneng; Chen, Yanqing; Liao, Baolin; Chen, Weilie; Hu, Fengyu; Zhang, Qing; Zhong, Mingqiu; Wu, Yanrong; Zhao, Lingzhai; Zhang, Fuchun; Cowling, Benjamin J.; Li, Fang; Leung, Gabriel M. (September 2020). "Author Correction: Temporal dynamics in viral shedding and transmissibility of COVID-19". Nature Medicine. 26 (9): 1491–1493. doi:10.1038/s41591-020-1016-z. PMC 7413015. PMID 32770170.

- ^ a b Ledford H (September 2020). "Coronavirus reinfections: three questions scientists are asking". Nature. 585 (7824): 168–169. doi:10.1038/d41586-020-02506-y. PMID 32887957. S2CID 221501940.

- ^ a b To KK, Hung IF, Ip JD, Chu AW, Chan WM, Tam AR, et al. (August 2020). "COVID-19 re-infection by a phylogenetically distinct SARS-coronavirus-2 strain confirmed by whole genome sequencing". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 73 (9): e2946–e2951. doi:10.1093/cid/ciaa1275. PMC 7499500. PMID 32840608. S2CID 221308584.

- ^ a b Tillett RL, Sevinsky JR, Hartley PD, Kerwin H, Crawford N, Gorzalski A, et al. (January 2021). "Genomic evidence for reinfection with SARS-CoV-2: a case study". The Lancet. Infectious Diseases. 21 (1): 52–58. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30764-7. PMC 7550103. PMID 33058797.

- ^ a b c Zhou P, Yang XL, Wang XG, Hu B, Zhang L, Zhang W, et al. (March 2020). "A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin". Nature. 579 (7798): 270–273. Bibcode:2020Natur.579..270Z. doi:10.1038/s41586-020-2012-7. PMC 7095418. PMID 32015507.

- ^ Eschner K (28 January 2020). "We're still not sure where the Wuhan coronavirus really came from". Popular Science. Archived from the original on 30 January 2020. Retrieved 30 January 2020.

- ^ Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Zhao J, Hu Y, et al. (February 2020). "Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China". Lancet. 395 (10223): 497–506. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. PMC 7159299. PMID 31986264.

- ^ a b Chen N, Zhou M, Dong X, Qu J, Gong F, Han Y, et al. (February 2020). "Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study". Lancet. 395 (10223): 507–513. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30211-7. PMC 7135076. PMID 32007143.

- ^ a b Cyranoski D (March 2020). "Mystery deepens over animal source of coronavirus". Nature. 579 (7797): 18–19. Bibcode:2020Natur.579...18C. doi:10.1038/d41586-020-00548-w. PMID 32127703.

- ^ Yu WB, Tang GD, Zhang L, Corlett RT (May 2020). "Decoding the evolution and transmissions of the novel pneumonia coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2 / HCoV-19) using whole genomic data". Zoological Research. 41 (3): 247–257. doi:10.24272/j.issn.2095-8137.2020.022. PMC 7231477. PMID 32351056.

- ^ a b c d e Report of the WHO-China Joint Mission on Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) (PDF) (Report). World Health Organization (WHO). 24 February 2020. Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 February 2020. Retrieved 5 March 2020.

- ^ Worobey M (December 2021). "Dissecting the early COVID-19 cases in Wuhan". Science. 374 (6572): 1202–1204. Bibcode:2021Sci...374.1202W. doi:10.1126/science.abm4454. PMID 34793199. S2CID 244403410.

- ^ Kang L, He G, Sharp AK, Wang X, Brown AM, Michalak P, Weger-Lucarelli J (August 2021). "A selective sweep in the Spike gene has driven SARS-CoV-2 human adaptation". Cell. 184 (17): 4392–4400.e4. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2021.07.007. PMC 8260498. PMID 34289344.

- ^ Decaro N, Lorusso A (May 2020). "Novel human coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2): A lesson from animal coronaviruses". Veterinary Microbiology. 244: 108693. doi:10.1016/j.vetmic.2020.108693. PMC 7195271. PMID 32402329.

- ^ Robson F, Khan KS, Le TK, Paris C, Demirbag S, Barfuss P, et al. (August 2020). "Coronavirus RNA Proofreading: Molecular Basis and Therapeutic Targeting [published correction appears in Mol Cell. 2020 Dec 17;80(6):1136-1138]". Molecular Cell. 79 (5): 710–727. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2020.07.027. PMC 7402271. PMID 32853546.

- ^ Tao K, Tzou PL, Nouhin J, Gupta RK, de Oliveira T, Kosakovsky Pond SL, et al. (December 2021). "The biological and clinical significance of emerging SARS-CoV-2 variants". Nature Reviews. Genetics. 22 (12): 757–773. doi:10.1038/s41576-021-00408-x. PMC 8447121. PMID 34535792.

- ^ Temmam, Sarah; Vongphayloth, Khamsing; Salazar, Eduard Baquero; Munier, Sandie; Bonomi, Max; Régnault, Béatrice; Douangboubpha, Bounsavane; Karami, Yasaman; Chretien, Delphine; Sanamxay, Daosavanh; Xayaphet, Vilakhan (February 2022). "Bat coronaviruses related to SARS-CoV-2 and infectious for human cells". Nature. 604 (7905): 330–336. Bibcode:2022Natur.604..330T. doi:10.1038/s41586-022-04532-4. PMID 35172323. S2CID 246902858.

- ^ Mallapaty, Smriti (24 September 2021). "Closest known relatives of virus behind COVID-19 found in Laos". Nature. 597 (7878): 603. Bibcode:2021Natur.597..603M. doi:10.1038/d41586-021-02596-2. PMID 34561634. S2CID 237626322.

- ^ "Newly Discovered Bat Viruses Give Hints to Covid's Origins". New York Times. 14 October 2021.

- ^ "Bat coronavirus isolate RaTG13, complete genome". National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). 10 February 2020. Archived from the original on 15 May 2020. Retrieved 5 March 2020.

- ^ "The 'Occam's Razor Argument' Has Not Shifted in Favor of a Lab Leak". Snopes.com. Snopes. Retrieved 18 July 2021.

- ^ Lu R, Zhao X, Li J, Niu P, Yang B, Wu H, et al. (February 2020). "Genomic characterisation and epidemiology of 2019 novel coronavirus: implications for virus origins and receptor binding". Lancet. 395 (10224): 565–574. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30251-8. PMC 7159086. PMID 32007145.

- ^ O'Keeffe J, Freeman S, Nicol A (21 March 2021). The Basics of SARS-CoV-2 Transmission. Vancouver, BC: National Collaborating Centre for Environmental Health (NCCEH). ISBN 978-1-988234-54-0. Archived from the original on 12 May 2021. Retrieved 12 May 2021.

- ^ Holmes EC, Goldstein SA, Rasmussen AL, Robertson DL, Crits-Christoph A, Wertheim JO, et al. (August 2021). "The Origins of SARS-CoV-2: A Critical Review". Cell. 184 (19): 4848–4856. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2021.08.017. PMC 8373617. PMID 34480864.

- ^ Xiao K, Zhai J, Feng Y, Zhou N, Zhang X, Zou JJ, et al. (July 2020). "Isolation of SARS-CoV-2-related coronavirus from Malayan pangolins". Nature. 583 (7815): 286–289. Bibcode:2020Natur.583..286X. doi:10.1038/s41586-020-2313-x. PMID 32380510. S2CID 218557880.

- ^ Zhao J, Cui W, Tian BP (2020). "The Potential Intermediate Hosts for SARS-CoV-2". Frontiers in Microbiology. 11: 580137. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2020.580137. PMC 7554366. PMID 33101254.

- ^ "Why it's so tricky to trace the origin of COVID-19". Science. National Geographic. 10 September 2021.

- ^ a b c Hu B, Guo H, Zhou P, Shi ZL (March 2021). "Characteristics of SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19". Nature Reviews. Microbiology. 19 (3): 141–154. doi:10.1038/s41579-020-00459-7. PMC 7537588. PMID 33024307.

- ^ Giovanetti M, Benedetti F, Campisi G, Ciccozzi A, Fabris S, Ceccarelli G, et al. (January 2021). "Evolution patterns of SARS-CoV-2: Snapshot on its genome variants". Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 538: 88–91. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2020.10.102. PMC 7836704. PMID 33199021. S2CID 226988090.

- ^ a b c V'kovski P, Kratzel A, Steiner S, Stalder H, Thiel V (March 2021). "Coronavirus biology and replication: implications for SARS-CoV-2". Nature Reviews. Microbiology. 19 (3): 155–170. doi:10.1038/s41579-020-00468-6. PMC 7592455. PMID 33116300.

- ^ a b Zhu N, Zhang D, Wang W, Li X, Yang B, Song J, et al. (February 2020). "A Novel Coronavirus from Patients with Pneumonia in China, 2019". The New England Journal of Medicine. 382 (8): 727–733. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2001017. PMC 7092803. PMID 31978945.

- ^ "Phylogeny of SARS-like betacoronaviruses". nextstrain. Archived from the original on 20 January 2020. Retrieved 18 January 2020.

- ^ Wong AC, Li X, Lau SK, Woo PC (February 2019). "Global Epidemiology of Bat Coronaviruses". Viruses. 11 (2): 174. doi:10.3390/v11020174. PMC 6409556. PMID 30791586.

- ^ a b Singh D, Yi SV (April 2021). "On the origin and evolution of SARS-CoV-2". Experimental & Molecular Medicine. 53 (4): 537–547. doi:10.1038/s12276-021-00604-z. PMC 8050477. PMID 33864026.

- ^ Jackson B, Boni MF, Bull MJ, Colleran A, Colquhoun RM, Darby AC, et al. (September 2021). "Generation and transmission of interlineage recombinants in the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic". Cell. 184 (20): 5179–5188.e8. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2021.08.014. PMC 8367733. PMID 34499854. S2CID 237099659.

- ^ a b "CoV2020". GISAID EpifluDB. Archived from the original on 12 January 2020. Retrieved 12 January 2020.

- ^ Kim D, Lee JY, Yang JS, Kim JW, Kim VN, Chang H (May 2020). "The Architecture of SARS-CoV-2 Transcriptome". Cell. 181 (4): 914–921.e10. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2020.04.011. PMC 7179501. PMID 32330414.

- ^ To KK, Sridhar S, Chiu KH, Hung DL, Li X, Hung IF, et al. (December 2021). "Lessons learned 1 year after SARS-CoV-2 emergence leading to COVID-19 pandemic". Emerging Microbes & Infections. 10 (1): 507–535. doi:10.1080/22221751.2021.1898291. PMC 8006950. PMID 33666147.

- ^ a b Jackson CB, Farzan M, Chen B, Choe H (January 2022). "Mechanisms of SARS-CoV-2 entry into cells". Nature Reviews. Molecular Cell Biology. 23 (1): 3–20. doi:10.1038/s41580-021-00418-x. PMC 8491763. PMID 34611326.

- ^ Braun E, Sauter D (2019). "Furin-mediated protein processing in infectious diseases and cancer". Clinical & Translational Immunology. 8 (8): e1073. doi:10.1002/cti2.1073. PMC 6682551. PMID 31406574.

- ^ Vankadari N (August 2020). "Structure of Furin Protease Binding to SARS-CoV-2 Spike Glycoprotein and Implications for Potential Targets and Virulence". The Journal of Physical Chemistry Letters. 11 (16): 6655–6663. doi:10.1021/acs.jpclett.0c01698. PMC 7409919. PMID 32787225.

- ^ a b Coutard B, Valle C, de Lamballerie X, Canard B, Seidah NG, Decroly E (April 2020). "The spike glycoprotein of the new coronavirus 2019-nCoV contains a furin-like cleavage site absent in CoV of the same clade". Antiviral Research. 176: 104742. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2020.03.022. PMC 7114094. PMID 32057769.

- ^ Zhang T, Wu Q, Zhang Z (April 2020). "Probable Pangolin Origin of SARS-CoV-2 Associated with the COVID-19 Outbreak". Current Biology. 30 (7): 1346–1351.e2. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2020.03.022. PMC 7156161. PMID 32197085.

- ^ Wu Y, Zhao S (December 2020). "Furin cleavage sites naturally occur in coronaviruses". Stem Cell Research. 50: 102115. doi:10.1016/j.scr.2020.102115. PMC 7836551. PMID 33340798.

- ^ Worobey M, Pekar J, Larsen BB, Nelson MI, Hill V, Joy JB, et al. (October 2020). "The emergence of SARS-CoV-2 in Europe and North America". Science. 370 (6516): 564–570. doi:10.1126/science.abc8169. PMC 7810038. PMID 32912998.

- ^ "Initial genome release of novel coronavirus". Virological. 11 January 2020. Archived from the original on 12 January 2020. Retrieved 12 January 2020.

- ^ a b Bedford T, Neher R, Hadfield N, Hodcroft E, Ilcisin M, Müller N. "Genomic analysis of nCoV spread: Situation report 2020-01-30". nextstrain.org. Archived from the original on 15 March 2020. Retrieved 18 March 2020.

- ^ Sun J, He WT, Wang L, Lai A, Ji X, Zhai X, et al. (May 2020). "COVID-19: Epidemiology, Evolution, and Cross-Disciplinary Perspectives". Trends in Molecular Medicine. 26 (5): 483–495. doi:10.1016/j.molmed.2020.02.008. PMC 7118693. PMID 32359479.

- ^ "Genomic epidemiology of novel coronavirus - Global subsampling". Nextstrain. 25 October 2021. Archived from the original on 20 April 2020. Retrieved 26 October 2021.

- ^ Coronaviridae Study Group of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (April 2020). "The species Severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus: classifying 2019-nCoV and naming it SARS-CoV-2". Nature Microbiology. 5 (4): 536–544. doi:10.1038/s41564-020-0695-z. PMC 7095448. PMID 32123347.

- ^ "New, more infectious strain of COVID-19 now dominates global cases of virus: study". medicalxpress.com. Archived from the original on 17 November 2020. Retrieved 16 August 2020.

- ^ Korber B, Fischer WM, Gnanakaran S, Yoon H, Theiler J, Abfalterer W, et al. (August 2020). "Tracking Changes in SARS-CoV-2 Spike: Evidence that D614G Increases Infectivity of the COVID-19 Virus". Cell. 182 (4): 812–827.e19. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2020.06.043. PMC 7332439. PMID 32697968.

- ^ Dhama K, Khan S, Tiwari R, Sircar S, Bhat S, Malik YS, et al. (September 2020). "Coronavirus Disease 2019-COVID-19". Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 33 (4). doi:10.1128/CMR.00028-20. PMC 7405836. PMID 32580969.

- ^ Dockrill P (11 November 2020). "Scientists Just Found a Mysteriously Hidden 'Gene Within a Gene' in SARS-CoV-2". ScienceAlert. Archived from the original on 17 November 2020. Retrieved 11 November 2020.

- ^ Nelson CW, Ardern Z, Goldberg TL, Meng C, Kuo CH, Ludwig C, et al. (October 2020). "Dynamically evolving novel overlapping gene as a factor in the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic". eLife. 9. doi:10.7554/eLife.59633. PMC 7655111. PMID 33001029. Archived from the original on 17 November 2020. Retrieved 11 November 2020.

- ^ a b Zhou H, Ji J, Chen X, Bi Y, Li J, Wang Q, et al. (June 2021). "Identification of novel bat coronaviruses sheds light on the evolutionary origins of SARS-CoV-2 and related viruses". Cell. 184 (17): 4380–4391.e14. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2021.06.008. PMC 8188299. PMID 34147139.

- ^ a b Wacharapluesadee S, Tan CW, Maneeorn P, Duengkae P, Zhu F, Joyjinda Y, et al. (February 2021). "Evidence for SARS-CoV-2 related coronaviruses circulating in bats and pangolins in Southeast Asia". Nature Communications. 12 (1): 972. Bibcode:2021NatCo..12..972W. doi:10.1038/s41467-021-21240-1. PMC 7873279. PMID 33563978.

- ^ Murakami S, Kitamura T, Suzuki J, Sato R, Aoi T, Fujii M, et al. (December 2020). "Detection and Characterization of Bat Sarbecovirus Phylogenetically Related to SARS-CoV-2, Japan". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 26 (12): 3025–3029. doi:10.3201/eid2612.203386. PMC 7706965. PMID 33219796.

- ^ a b Zhou H, Chen X, Hu T, Li J, Song H, Liu Y, et al. (June 2020). "A Novel Bat Coronavirus Closely Related to SARS-CoV-2 Contains Natural Insertions at the S1/S2 Cleavage Site of the Spike Protein". Current Biology. 30 (11): 2196–2203.e3. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2020.05.023. PMC 7211627. PMID 32416074.

- ^ Lam TT, Jia N, Zhang YW, Shum MH, Jiang JF, Zhu HC, et al. (July 2020). "Identifying SARS-CoV-2-related coronaviruses in Malayan pangolins". Nature. 583 (7815): 282–285. Bibcode:2020Natur.583..282L. doi:10.1038/s41586-020-2169-0. PMID 32218527. S2CID 214683303.

- ^ Xiao, Kangpeng; Zhai, Junqiong; Feng, Yaoyu; Zhou, Niu; Zhang, Xu; Zou, Jie-Jian; Li, Na; Guo, Yaqiong; Li, Xiaobing; Shen, Xuejuan; Zhang, Zhipeng; Shu, Fanfan; Huang, Wanyi; Li, Yu; Zhang, Ziding; Chen, Rui-Ai; Wu, Ya-Jiang; Peng, Shi-Ming; Huang, Mian; Xie, Wei-Jun; Cai, Qin-Hui; Hou, Fang-Hui; Chen, Wu; Xiao, Lihua; Shen, Yongyi (9 July 2020). "Isolation of SARS-CoV-2-related coronavirus from Malayan pangolins". Nature. 583 (7815): 286–289. doi:10.1038/s41586-020-2313-x.

- ^ a b Delaune, Deborah; Hul, Vibol; Karlsson, Erik A.; Hassanin, Alexandre; Ou, Tey Putita; Baidaliuk, Artem; Gámbaro, Fabiana; Prot, Matthieu; Tu, Vuong Tan; Chea, Sokha; Keatts, Lucy; Mazet, Jonna; Johnson, Christine K.; Buchy, Philippe; Dussart, Philippe; Goldstein, Tracey; Simon-Lorière, Etienne; Duong, Veasna (9 November 2021). "A novel SARS-CoV-2 related coronavirus in bats from Cambodia". Nature Communications. 12 (1): 6563. doi:10.1038/s41467-021-26809-4. ISSN 2041-1723.

- ^ Zhou H, Chen X, Hu T, Li J, Song H, Liu Y, et al. (June 2020). "A Novel Bat Coronavirus Closely Related to SARS-CoV-2 Contains Natural Insertions at the S1/S2 Cleavage Site of the Spike Protein". Current Biology. 30 (11): 2196–2203.e3. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2020.05.023. PMC 7211627. PMID 32416074.

- ^ Zhou, Peng; Yang, Xing-Lou; Wang, Xian-Guang; Hu, Ben; Zhang, Lei; Zhang, Wei; Si, Hao-Rui; Zhu, Yan; Li, Bei; Huang, Chao-Lin; Chen, Hui-Dong; Chen, Jing; Luo, Yun; Guo, Hua; Jiang, Ren-Di; Liu, Mei-Qin; Chen, Ying; Shen, Xu-Rui; Wang, Xi; Zheng, Xiao-Shuang; Zhao, Kai; Chen, Quan-Jiao; Deng, Fei; Liu, Lin-Lin; Yan, Bing; Zhan, Fa-Xian; Wang, Yan-Yi; Xiao, Geng-Fu; Shi, Zheng-Li (12 March 2020). "A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin". Nature. 579 (7798): 270–273. doi:10.1038/s41586-020-2012-7.

- ^ Temmam, Sarah; Vongphayloth, Khamsing; Baquero, Eduard; Munier, Sandie; Bonomi, Massimiliano; Regnault, Béatrice; Douangboubpha, Bounsavane; Karami, Yasaman; Chrétien, Delphine; Sanamxay, Daosavanh; Xayaphet, Vilakhan; Paphaphanh, Phetphoumin; Lacoste, Vincent; Somlor, Somphavanh; Lakeomany, Khaithong; Phommavanh, Nothasin; Pérot, Philippe; Dehan, Océane; Amara, Faustine; Donati, Flora; Bigot, Thomas; Nilges, Michael; Rey, Félix A.; van der Werf, Sylvie; Brey, Paul T.; Eloit, Marc (16 February 2022). "Bat coronaviruses related to SARS-CoV-2 and infectious for human cells". Nature. doi:10.1038/s41586-022-04532-4.

- ^ Koyama T, Platt D, Parida L (July 2020). "Variant analysis of SARS-CoV-2 genomes". Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 98 (7): 495–504. doi:10.2471/BLT.20.253591. PMC 7375210. PMID 32742035.

We detected in total 65776 variants with 5775 distinct variants.

- ^ Alm E, Broberg EK, Connor T, Hodcroft EB, Komissarov AB, Maurer-Stroh S, et al. (August 2020). "Geographical and temporal distribution of SARS-CoV-2 clades in the WHO European Region, January to June 2020". Euro Surveillance. 25 (32). doi:10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.32.2001410. PMC 7427299. PMID 32794443.

- ^ World Health Organization (27 November 2021). "Tracking SARS-CoV-2 variants". World Health Organization. Archived from the original on 6 June 2021. Retrieved 28 November 2021.

- ^ "SARS-CoV-2 mink-associated variant strain – Denmark". WHO. 3 December 2020. Archived from the original on 31 December 2020. Retrieved 30 December 2020.

- ^ Sender R, Bar-On YM, Gleizer S, Bernsthein B, Flamholz A, Phillips R, Milo R (April 2021). "The total number and mass of SARS-CoV-2 virions". medRxiv: 2020.11.16.20232009. doi:10.1101/2020.11.16.20232009. PMC 7685332. PMID 33236021.

- ^ a b c Wu C, Liu Y, Yang Y, Zhang P, Zhong W, Wang Y, et al. (May 2020). "Analysis of therapeutic targets for SARS-CoV-2 and discovery of potential drugs by computational methods". Acta Pharmaceutica Sinica B. 10 (5): 766–788. doi:10.1016/j.apsb.2020.02.008. PMC 7102550. PMID 32292689.

- ^ a b Wrapp D, Wang N, Corbett KS, Goldsmith JA, Hsieh CL, Abiona O, et al. (March 2020). "Cryo-EM structure of the 2019-nCoV spike in the prefusion conformation". Science. 367 (6483): 1260–1263. Bibcode:2020Sci...367.1260W. doi:10.1126/science.abb2507. PMC 7164637. PMID 32075877.

- ^ Mandelbaum RF (19 February 2020). "Scientists Create Atomic-Level Image of the New Coronavirus's Potential Achilles Heel". Gizmodo. Archived from the original on 8 March 2020. Retrieved 13 March 2020.

- ^ Sokhansanj, Bahrad A.; Rosen, Gail L. (26 April 2022). Gaglia, Marta M. (ed.). "Mapping Data to Deep Understanding: Making the Most of the Deluge of SARS-CoV-2 Genome Sequences". mSystems. 7 (2): e00035–22. doi:10.1128/msystems.00035-22. ISSN 2379-5077. PMC 9040592. PMID 35311562.

- ^ Kandeel M, Ibrahim A, Fayez M, Al-Nazawi M (June 2020). "From SARS and MERS CoVs to SARS-CoV-2: Moving toward more biased codon usage in viral structural and nonstructural genes". Journal of Medical Virology. 92 (6): 660–666. doi:10.1002/jmv.25754. PMC 7228358. PMID 32159237.

- ^ a b Hou W (September 2020). "Characterization of codon usage pattern in SARS-CoV-2". Virology Journal. 17 (1): 138. doi:10.1186/s12985-020-01395-x. PMC 7487440. PMID 32928234.

- ^ a b Wang Y, Mao JM, Wang GD, Luo ZP, Yang L, Yao Q, Chen KP (July 2020). "Human SARS-CoV-2 has evolved to reduce CG dinucleotide in its open reading frames". Scientific Reports. 10 (1): 12331. Bibcode:2020NatSR..1012331W. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-69342-y. PMC 7378049. PMID 32704018.

- ^ Rice AM, Castillo Morales A, Ho AT, Mordstein C, Mühlhausen S, Watson S, et al. (January 2021). "Evidence for Strong Mutation Bias toward, and Selection against, U Content in SARS-CoV-2: Implications for Vaccine Design". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 38 (1): 67–83. doi:10.1093/molbev/msaa188. PMC 7454790. PMID 32687176.

- ^ Gu H, Chu DK, Peiris M, Poon LL (January 2020). "Multivariate analyses of codon usage of SARS-CoV-2 and other betacoronaviruses". Virus Evolution. 6 (1): veaa032. doi:10.1093/ve/veaa032. PMC 7223271. PMID 32431949.

- ^ Wang Q, Zhang Y, Wu L, Niu S, Song C, Zhang Z, et al. (May 2020). "Structural and Functional Basis of SARS-CoV-2 Entry by Using Human ACE2". Cell. 181 (4): 894–904.e9. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2020.03.045. PMC 7144619. PMID 32275855.

- ^ Xu X, Chen P, Wang J, Feng J, Zhou H, Li X, et al. (March 2020). "Evolution of the novel coronavirus from the ongoing Wuhan outbreak and modeling of its spike protein for risk of human transmission". Science China Life Sciences. 63 (3): 457–460. doi:10.1007/s11427-020-1637-5. PMC 7089049. PMID 32009228.

- ^ Letko M, Marzi A, Munster V (April 2020). "Functional assessment of cell entry and receptor usage for SARS-CoV-2 and other lineage B betacoronaviruses". Nature Microbiology. 5 (4): 562–569. doi:10.1038/s41564-020-0688-y. PMC 7095430. PMID 32094589.

- ^ Letko M, Marzi A, Munster V (April 2020). "Functional assessment of cell entry and receptor usage for SARS-CoV-2 and other lineage B betacoronaviruses". Nature Microbiology. 5 (4): 562–569. doi:10.1038/s41564-020-0688-y. PMC 7095430. PMID 32094589.

- ^ El Sahly HM. "Genomic Characterization of the 2019 Novel Coronavirus". The New England Journal of Medicine. Archived from the original on 17 February 2020. Retrieved 9 February 2020.

- ^ "Novel coronavirus structure reveals targets for vaccines and treatments". National Institutes of Health (NIH). 2 March 2020. Archived from the original on 1 April 2020. Retrieved 3 April 2020.

- ^ Wang K, Chen W, Zhang Z, Deng Y, Lian JQ, Du P, et al. (December 2020). "CD147-spike protein is a novel route for SARS-CoV-2 infection to host cells". Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy. 5 (1): 283. bioRxiv 10.1101/2020.03.14.988345. doi:10.1038/s41392-020-00426-x. PMC 7714896. PMID 33277466. S2CID 214725955.

- ^ Zamorano Cuervo N, Grandvaux N (November 2020). "ACE2: Evidence of role as entry receptor for SARS-CoV-2 and implications in comorbidities". eLife. 9. doi:10.7554/eLife.61390. PMC 7652413. PMID 33164751.

- ^ "Anatomy of a Killer: Understanding SARS-CoV-2 and the drugs that might lessen its power". The Economist. 12 March 2020. Archived from the original on 14 March 2020. Retrieved 14 March 2020.

- ^ Beeching NJ, Fletcher TE, Fowler R (22 May 2020). "BMJ Best Practice: Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19)" (PDF). BMJ. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 June 2020. Retrieved 25 May 2020.

- ^ Drayman N, DeMarco JK, Jones KA, Azizi SA, Froggatt HM, Tan K, et al. (August 2021). "Masitinib is a broad coronavirus 3CL inhibitor that blocks replication of SARS-CoV-2". Science. 373 (6557): 931–936. Bibcode:2021Sci...373..931D. doi:10.1126/science.abg5827. PMC 8809056. PMID 34285133.

- ^ Fact sheet for healthcare providers: Emergency Use Authorization for Paxlovid (PDF) (Technical report). Pfizer. 22 December 2021. LAB-1492-0.8. Archived from the original on 23 December 2021.

- ^ "Paxlovid EPAR". European Medicines Agency (EMA). 24 January 2022. Retrieved 3 February 2022. 텍스트는 이 소스(저작권 유럽 의약품청)에서 복사한 것입니다.출처가 확인되면 복제가 허가됩니다.

- ^ "Oral COVID-19 antiviral, Paxlovid, approved by UK regulator" (Press release). Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency. 31 December 2021.

- ^ "Health Canada authorizes Paxlovid for patients with mild to moderate COVID-19 at high risk of developing serious disease". Health Canada (Press release). 17 January 2022. Retrieved 24 April 2022.

- ^ "FDA Authorizes First Oral Antiviral for Treatment of COVID-19". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (Press release). 22 December 2021. Retrieved 22 December 2021.

이 문서에는 퍼블릭 도메인에 있는 이 소스로부터의 텍스트가 포함되어 있습니다..

이 문서에는 퍼블릭 도메인에 있는 이 소스로부터의 텍스트가 포함되어 있습니다.. - ^ Whipple T (23 October 2021). "Moonshot is the spanner in the Covid-19 works the country needs". The Times. Retrieved 5 November 2021.

- ^ Rocklöv J, Sjödin H, Wilder-Smith A (May 2020). "COVID-19 outbreak on the Diamond Princess cruise ship: estimating the epidemic potential and effectiveness of public health countermeasures". Journal of Travel Medicine. 27 (3). doi:10.1093/jtm/taaa030. PMC 7107563. PMID 32109273.

- ^ Ke R, Romero-Severson E, Sanche S, Hengartner N (May 2021). "Estimating the reproductive number R0 of SARS-CoV-2 in the United States and eight European countries and implications for vaccination". Journal of Theoretical Biology. 517: 110621. Bibcode:2021JThBi.51710621K. doi:10.1016/j.jtbi.2021.110621. PMC 7880839. PMID 33587929.

- ^ Liu Y, Gayle AA, Wilder-Smith A, Rocklöv J (March 2020). "The reproductive number of COVID-19 is higher compared to SARS coronavirus". Journal of Travel Medicine. 27 (2): taaa021. doi:10.1093/jtm/taaa021. PMC 7074654. PMID 32052846.

- ^ Davies NG, Abbott S, Barnard RC, Jarvis CI, Kucharski AJ, Munday JD, et al. (April 2021). "Estimated transmissibility and impact of SARS-CoV-2 lineage B.1.1.7 in England". Science. 372 (6538): eabg3055. doi:10.1126/science.abg3055. PMC 8128288. PMID 33658326.

- ^ Liu Y, Rocklöv J (October 2021). "The reproductive number of the Delta variant of SARS-CoV-2 is far higher compared to the ancestral SARS-CoV-2 virus". Journal of Travel Medicine. 28 (7): taab124. doi:10.1093/jtm/taab124. PMC 8436367. PMID 34369565.

- ^ a b c d "COVID-19 Dashboard by the Center for Systems Science and Engineering (CSSE) at Johns Hopkins University (JHU)". ArcGIS. Johns Hopkins University. Retrieved 29 July 2022.

- ^ Branswell H (30 January 2020). "Limited data on coronavirus may be skewing assumptions about severity". STAT. Archived from the original on 1 February 2020. Retrieved 13 March 2020.

- ^ Wu JT, Leung K, Leung GM (February 2020). "Nowcasting and forecasting the potential domestic and international spread of the 2019-nCoV outbreak originating in Wuhan, China: a modelling study". Lancet. 395 (10225): 689–697. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30260-9. PMC 7159271. PMID 32014114.

- ^ Boseley S, McCurry J (30 January 2020). "Coronavirus deaths leap in China as countries struggle to evacuate citizens". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 6 February 2020. Retrieved 10 March 2020.

- ^ Paulinus A (25 February 2020). "Coronavirus: China to repay Africa in safeguarding public health". The Sun. Archived from the original on 9 March 2020. Retrieved 10 March 2020.

추가 정보

- Bar-On YM, Flamholz A, Phillips R, Milo R (April 2020). "SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) by the numbers". eLife. 9. arXiv:2003.12886. Bibcode:2020arXiv200312886B. doi:10.7554/eLife.57309. PMC 7224694. PMID 32228860.

- Brüssow H (May 2020). "The Novel Coronavirus - A Snapshot of Current Knowledge". Microbial Biotechnology. 13 (3): 607–612. doi:10.1111/1751-7915.13557. PMC 7111068. PMID 32144890.

- Cascella M, Rajnik M, Aleem A, Dulebohn S, Di Napoli R (January 2020). "Features, Evaluation and Treatment Coronavirus (COVID-19)". StatPearls. PMID 32150360. Archived from the original on 6 April 2020. Retrieved 4 April 2020.

- Laboratory testing for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in suspected human cases (Report). World Health Organization. 2 March 2020. hdl:10665/331329.

- Zoumpourlis V, Goulielmaki M, Rizos E, Baliou S, Spandidos DA (October 2020). "[Comment] The COVID‑19 pandemic as a scientific and social challenge in the 21st century". Molecular Medicine Reports (Review). 22 (4): 3035–3048. doi:10.3892/mmr.2020.11393. PMC 7453598. PMID 32945405.

외부 링크

- "Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19)". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 11 February 2020.

- "Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) Pandemic". World Health Organization (WHO).

- "SARS-CoV-2 (Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2) Sequences". National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI).

- "COVID-19 Resource Centre". The Lancet.

- "Coronavirus (Covid-19)". The New England Journal of Medicine.

- "Covid-19: Novel Coronavirus Outbreak". Wiley.

- "SARS-CoV-2". Virus Pathogen Database and Analysis Resource.

- "SARS-CoV-2 related protein structures". Protein Data Bank.