필리핀

Philippines필리핀 공화국 필리피나스 공화국 (필리피노) | |

|---|---|

| 모토: Maka-Diyos, Maka-tao, Makakalikasan at Makabansa[1] "신을 위하여, 사람을 위하여, 자연을 위하여, 나라를 위하여" | |

| 국가: "루팡 히니랑" 초이스랜드 | |

| 자본의 | 마닐라 (법무) 메트로[a] 마닐라 (사실상) |

| 최대도시 | 케손 시 |

| 공용어 | |

| 인정된 지역 언어 | 19개 국어[4] |

| 필리핀 수화 | |

기타 인정 언어[b] | 스페인어와 아랍어 |

| 민족 (2010[6]) | |

| 종교 (2015)[6] | |

| 데모니온 | 필리핀 사람 (중립) 필리핀어 (feminine) 피노이 (특정 공통명사에 대한 adjective) |

| 정부 | 단일 대통령제헌공화국 |

• 프레지던트 | 봉봉 마르코스 |

• 부통령 | 사라 두테르테 |

• 상원의장 | Migz Zubiri |

• 하원의장 | 마르틴 로무알데즈 |

• 대법원장 | 알렉산더 게스문도 |

| 입법부 | 의회 |

• 참의원 | 상원 |

• 하원 | 하원 |

| 독립 | |

• 선언 | 1898년 6월 12일 |

• 세션 | 1898년 12월 10일 |

• 자치정부 | 1935년 11월 15일 |

• 인정됨 | 1946년7월4일 |

• 헌법 | 1987년2월2일 |

| 지역 | |

• 토탈 | 30만 km2 (120,000 sqmi).[7][8]: 15 [9][10] (72~69위) |

• 물(%) | 0.61 (inland) |

| 인구. | |

• 2020년 인구조사 | 109,035,343[12] |

• 밀도 | 363.45/km2 (941.3/sq mi) (37th) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2023년 추계 |

• 토탈 | |

• 인당 | |

| GDP (nominal) | 2023년 추계 |

• 토탈 | |

• 인당 | |

| 지니 (2021) | 중간의 |

| HDI (2021) | 중 · 116위 |

| 통화 | 필리핀 페소(₱)(PHP) |

| 시간대 | UTC+08:00 (PhST) |

| 운전측 | 맞음[16] |

| 호출코드 | +63 |

| ISO 3166 코드 | PH |

| 인터넷 TLD | .ph |

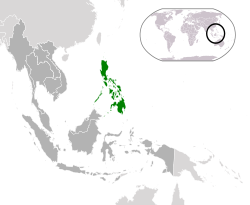

필리핀(/ ˈ ɪ ɪpi ːnz/; 필리핀어: 필리핀 공화국(),[17] 공식적으로는 필리핀 공화국(필리핀: 필리핀 공화국)[c]은 동남아시아의 군도 국가입니다. 서태평양에는 7,641개의 섬으로 구성되어 있으며 총 면적은 300,000 평방 킬로미터로 루손, 비사야스, 민다나오의 세 가지 주요 지리적 구분으로 크게 분류됩니다.[7] 필리핀은 서쪽으로는 남중국해, 동쪽으로는 필리핀해, 그리고 남쪽으로는 셀레베스해와 접해 있습니다. 북쪽으로는 대만, 북동쪽으로는 일본, 동쪽과 남동쪽으로는 팔라우, 남쪽으로는 인도네시아, 남서쪽으로는 말레이시아, 서쪽으로는 베트남, 북서쪽으로는 중국과 해양 국경을 접하고 있습니다. 이 나라는 다양한 민족과 문화를 가진 세계에서 12번째로 인구가 많은 나라입니다. 마닐라는 필리핀의 수도이며, 가장 인구가 많은 도시는 케손 시이며, 둘 다 메트로 마닐라 내에 있습니다.

그 군도의 가장 초기 주민인 네그리토스는 오스트로네시아 사람들의 파도가 뒤따랐습니다. 애니미즘, 불교적 영향력을 가진 힌두교, 그리고 이슬람교의 채택으로 다투스, 라자, 그리고 술탄에 의해 지배되는 섬 왕국이 세워졌습니다. 후기[18] 당나라나[19] 송나라와 같은 이웃 국가들과의 해외 무역은 신어권 상인들을 열도로 불러들였고, 그들은 점차 정착과 혼화를 이루게 됩니다. 스페인으로 가는 함대를 이끌고 있는 포르투갈 탐험가 페르디난드 마젤란의 도착은 스페인 식민지화의 시작을 알렸습니다. 1543년, 스페인 탐험가 루이 로페스 데 비야로보스는 카스티야의 왕 필립 2세를 기리기 위해 이 군도를 라 이슬라스 필리피나스라고 이름 지었습니다. 1565년에 시작된 뉴 스페인을 통한 스페인의 식민지화는 필리핀이 300년 이상 스페인 제국의 일부로서 카스티야 왕가의 지배를 받도록 이끌었습니다. 가톨릭교가 지배적인 종교가 되었고 마닐라는 태평양 횡단 무역의 서부 중심지가 되었습니다. 라틴 아메리카와 이베리아 출신의 히스패닉 이민자들도 선택적으로 식민지화할 것입니다. 필리핀 혁명은 1896년에 시작되었고, 1898년 스페인-미국 전쟁과 얽히게 되었습니다. 스페인은 그 영토를 미국에 양도했고, 필리핀 혁명가들은 필리핀 제1공화국을 선포했습니다. 이어진 필리핀-미국 전쟁은 2차 세계 대전 동안 일본의 섬 침략이 있을 때까지 미국이 그 영토를 지배하면서 끝이 났습니다. 미국이 일본으로부터 필리핀을 되찾은 후, 필리핀은 1946년에 독립하였습니다. 이 나라는 비폭력 혁명으로 수십 년간 지속된 독재 정권의 타도를 포함한 민주주의에 대해 격동의 경험을 했습니다.

필리핀은 신흥 시장이자 새로운 산업화 국가로 경제가 농업 중심에서 서비스 및 제조업 중심으로 전환되고 있습니다. 유엔, 세계무역기구, 아세안, 아태경제협력포럼, 동아시아정상회의 등의 창립 회원국이며, 비동맹운동의 회원국이자 미국의 주요 비 NATO 동맹국입니다. 태평양 불의 고리에 있는 섬나라이고 적도에 가깝기 때문에 지진과 태풍이 발생하기 쉽습니다. 필리핀은 다양한 천연자원과 세계적으로 중요한 수준의 생물다양성을 가지고 있습니다.

어원

1542년 스페인 탐험가 루이 로페스 데 비야로보스는 카스티야의 왕 필립 2세(당시 아스투리아스의 왕자)의 이름을 따서 레이테 섬과 사마르 섬을 "펠리피나스"라고 이름 지었습니다. 결국, "Las Islas Philipinas"라는 이름은 이 군도의 스페인 소유지에 사용될 것입니다.[20]: 6 "Islas del Poniente" (서부 제도), "Islas del Oriente" (동부 제도), Ferdinand Magellan의 이름, "San Lázaro" (성 라자루스 섬)과 같은 다른 이름들은 스페인의 통치가 확립되기 전에 스페인 사람들이 이 지역의 섬들을 가리키는 데 사용되었습니다.[21][22][23]

필리핀 혁명 당시 말롤로스 의회는 필리핀 공화국을 선포했습니다.[24] 미국 식민지 당국은 이 나라를 필리핀 제도(스페인 이름의 번역본)라고 불렀습니다.[25] 미국은 필리핀 자치법과 존스 법에서 "필리핀 제도"에서 "필리핀"으로 명명법을 바꾸기 시작했습니다.[26] 공식 명칭인 "필리핀 공화국"은 1935년 헌법에 미래의 독립 국가의 이름으로 포함되었고,[27] 이후의 모든 헌법 개정에 포함되었습니다.[28][29]

역사

선사(900년 이전)

709,000년 전에 지금의 필리핀에 살았던 초기 호미닌의 증거가 있습니다.[30] 칼라오 동굴의 소수의 뼈는 잠재적으로 5만년에서 6만7천년 전에 살았던 다른 알려지지 않은 종인 호모 루조넨시스를 나타냅니다.[31][32] 이 섬에서 가장 오래된 현대 인류의 유해는 47,000 ± 11–10,000년 전의 팔라완의 타본 동굴에서 나온 것입니다.[33] 타본 맨(Tabon Man)은 아마도 네그리토(Negrito)로 추정되는데, 이 군도의 초기 주민들 중 하나는 남부 아시아를 따라 해안 길을 통해 아프리카를 벗어나 지금은 해질녘의 순달란드(Sundaland)와 사훌(Sahul)의 육지로 이동한 첫 번째 인류의 후손입니다.[34]

최초의 오스트로네시아인들은 기원전 2200년경 대만에서 필리핀에 도착하여 바타네스 제도([35]이장으로 알려진 돌 요새를 건설한 곳)와 루손 북부에 정착했습니다. 옥 유물은 기원전 2000년으로 거슬러 올라가며,[36][37] 대만의 원자재로 루손에서 만들어진 링잉오 옥 유물이 있습니다.[38] 기원전 1000년경, 이 군도의 주민들은 4개의 사회로 발전했습니다: 수렵채집 부족, 전사 사회, 고지대 금권, 항구 공국.[39]

초기 주 (900–1565)

필리핀에서 현존하는 가장 오래된 기록은 서기 10세기 초 라구나 동판 비문으로, 초기 카위 문자를 사용하여 여러 기술 산스크리트어 단어와 고대 자바어 또는 고대 타갈로그어 존칭을 사용하여 고대 말레이어로 쓰여진 것입니다.[40] 14세기에 이르러 몇몇 대규모 해안 정착지가 무역의 중심지로 등장하여 사회 변화의 중심지가 되었습니다.[41] 일부 정책은 아시아 전역의 다른 주와 교류했습니다.[42]: 3 [43] 중국과의 무역은 당나라 시대에 시작되어 송나라 시대에 확대된 것으로 보이며,[44] 서기 2천년경에는 중국의 지류 시스템의 일부로 일부 정책이 포함되었습니다.[20]: 177–178 [42]: 3 언어적 용어와 종교적 관습과 같은 인도 문화적 특성은 아마도 힌두교 마자파히트 제국을 통해 14세기 동안 필리핀에 퍼지기 시작했습니다.[45][46] 15세기까지 이슬람교는 술루 군도에 세워졌고 그곳에서 전파되었습니다.[41]

10세기에서 16세기 사이에 필리핀에 세워진 정치는 메이닐라,[47] 톤도, 나마얀, 팡가시난, 세부, 부투안, 마구인다나오, 라나오, 술루, 마이 등이 있습니다.[48] 초기 정치는 일반적으로 귀족, 자유인, 그리고 의존적 채무자-채권자라는 세 계층의 사회 구조를 가지고 있었습니다.[42]: 3 [49]: 672 귀족들 중에는 자치 단체(바랑가이 또는 둘로한)를 통치하는 데 책임이 있는 다투스(datus)라고 알려진 지도자들도 있었습니다.[50] 바랑가이들이 연합하여 더 큰 정착지를 형성하거나 지리적으로 더 느슨한 동맹을 형성할 때,[42]: 3 [51] 그들이 더 존경하는 구성원들은 "파라마운틴 다투",[52]: 58 [39] 라자 또는 술탄으로 인정받고 [53]공동체를 지배할 것입니다.[54] 태풍의 빈도와 필리핀이 태평양 불의 고리에 위치하고 있기 때문에 14세기에서 16세기[52]: 18 동안 인구 밀도가 낮았던 것으로 생각됩니다.[55] 포르투갈 탐험가 페르디난드 마젤란은 1521년에 도착하여 스페인을 위해 이 섬들을 영유하고 막탄 전투에서 라풀라푸의 부하들에게 죽임을 당했습니다.[56]: 21 [57]: 261

스페인과 미국의 식민지 지배 (1565–1946)

카스티야 왕가에 의한 통일과 식민지화는 스페인 탐험가 미겔 로페스 데 레가즈피가 뉴 스페인(스페인어: Nueva España) in 1565.[58][59][60]: 20–23 많은 필리핀 사람들은 노예와 강제 선원으로 뉴 스페인에 끌려왔습니다.[61] 스페인 마닐라는 1571년에 아시아와 태평양의 스페인 영토인 [62][63]스페인령 동인도의 수도가 되었습니다.[64] 스페인은 분할과 정복의 원칙을 사용하여 각 지방을 침공하여 [57]: 374 현재의 필리핀 대부분을 하나의 통합된 행정 하에 두었습니다.[65][66] 이질적인 바랑가이들은 의도적으로 마을로 통합되었고, 가톨릭 선교사들은 그들의 주민들을 더 쉽게 기독교로 개종시킬 수 있었습니다.[67]: 53, 68 [68] 그것은 처음에는 싱크레티즘이었습니다.[69] 1565년부터 1821년까지 필리핀은 멕시코 시티에 위치한 뉴 스페인 총독부의 영토로 통치되었으며, 그 후 멕시코 독립 전쟁이 끝난 후 마드리드에서 관리되었습니다.[70]: 81 마닐라는 비콜과 카비테에 건설된 마닐라 갤리온에 의해 태평양 횡단 무역의[71] 서부 중심지가 되었습니다.[72][73]

During its rule, Spain nearly bankrupted its treasury quelling indigenous revolts[70]: 111–122 and defending against external military attacks,[74]: 1077 [75] including Moro piracy,[76] a 17th-century war against the Dutch, 18th-century British occupation of Manila, and conflict with Muslims in the south.[77]: 4 [undue weight? ]

필리핀의 행정은 뉴 스페인의 경제에 손실을 주는 것으로 여겨졌고,[74]: 1077 그것을 포기하거나 다른 영토와 거래하는 것이 논의되었습니다. 섬들의 경제적 잠재력과 안보, 그리고 이 지역에서 종교적 개종을 계속하고자 하는 열망 때문에 이 같은 행동은 반대되었습니다.[52]: 7–8 [78] 식민지는 평균 25만 페소의 스페인 왕관의[74]: 1077 연간 보조금으로 생존했으며,[52]: 8 보통 아메리카 대륙에서 온 75톤의 은괴로 지불됩니다.[79] 7년 전쟁 동안 1762년부터 1764년까지 영국군이 마닐라를 점령했고, 1763년 파리 조약으로 스페인의 통치가 회복되었습니다.[60]: 81–83 스페인 사람들은 동남아시아의 이슬람교도들과의 전쟁을 레콘키스타의 확장으로 여겼습니다.[80][81] 스페인-모로 전쟁은 수백 년 동안 지속되었고, 스페인은 19세기의 마지막 분기 동안 민다나오와 졸로의 일부를 정복했고,[82] 술루 술탄국의 무슬림 모로는 스페인의 주권을 인정했습니다.[83][84]

필리핀 항구는 19세기 동안 세계 무역에 개방되었고, 필리핀 사회는 변화하기 시작했습니다.[85][86] 필리핀에서 태어난 스페인 사람들만을 지칭하는 대신 필리핀 사람이라는 용어가 군도의 모든 주민들을 포괄하면서 사회 정체성이 변했습니다.[87][88]

1872년 운동권 가톨릭 사제 3명이 의문의 여지가 있는 이유로 처형된 후 혁명 감정이 커졌습니다.[89][90] 이것은 필리핀의 정치 개혁을 지지했던 마르셀로 H. 델 필라르, 호세 리잘, 그라시아노 로페스 예나, 마리아노 폰세에 의해 조직된 프로파간다 운동에 영감을 주었습니다.[91] 리잘은 1896년 12월 30일 반란으로 처형되었고, 그의 죽음은 스페인에 충성했던 많은 사람들을 급진적으로 변화시켰습니다.[92] 개혁 시도는 저항에 부딪혔고, 안드레스 보니파시오는 1892년 무장 반란을 통해 스페인으로부터 독립하려는 카티푸난 비밀 결사를 설립했습니다.[70]: 137

푸가드 로인의 카티푸난의 외침은 1896년에 필리핀 혁명을 시작했습니다.[93] 내부 분쟁은 테제로스 협약으로 이어졌고, 보니파시오는 그의 자리를 잃고 에밀리오 아기날도가 혁명의 새로운 지도자로 선출되었습니다.[94]: 145–147 1897년 비아크나바토 조약으로 홍콩 군사정부는 망명정부로 이어졌습니다. 이듬해 스페인-미국 전쟁이 시작되어 필리핀에 도달했고 아기날도는 돌아와 혁명을 재개하고 1898년 6월 12일 스페인으로부터 독립을 선언했습니다.[95]: 26 1898년 12월, 이 섬들은 스페인-미국 전쟁 이후 푸에르토리코, 괌과 함께 스페인에 의해 미국에 양도되었습니다.[96][97]

필리핀 제1공화국은 1899년 1월 21일에 공포되었습니다.[98] 미국의 인정 부족으로 인해 미국의 현장 군 사령관이 휴전 제안과 신생 공화국의 선전포고를 거부한 [d]후 필리핀-미국 전쟁으로 확대된 적대 행위가 발생했습니다.[99][100][101][102]

그 전쟁은 주로 기근과 질병으로 인해 25만에서 100만 명의 민간인이 사망하는 결과를 낳았습니다.[103] 많은 필리핀인들이 미국인들에 의해 강제 수용소로 이송되었고, 그곳에서 수천 명이 사망했습니다.[104][105] 1902년 필리핀 제1공화국이 멸망한 후 필리핀 유기농법으로 미국 민간정부가 수립되었습니다.[106] 미군은 필리핀 공화국의 확장 시도를 억제하고,[94]: 200–202 [103] 술루 술탄국을 확보하고,[107][108] 스페인 정복에 저항하던 내륙 산간 지역의 통제권을 확립하면서, 이 섬들에 대한 그들의 통제권을 계속 확보하고 확장해 나갔습니다.[109] 그리고 기독교인들의 대규모 재정착을 장려했습니다. 한 때 주로 무슬림이었던 민다나오에서 말이죠.[110][111]

문화적 발전은 국가 정체성을 [112][113]: 12 강화시켰고 타갈로그어는 다른 지역 언어보다 우선시되기 시작했습니다.[67]: 121 태프트 위원회는 필리핀인들에게 정치적 기능을 점진적으로 [74]: 1081, 1117 부여했고, 1934년 타이딩스-맥더피 법은 마누엘 케손 대통령과 세르지오 오스메냐 부통령이 [114]다음 해 필리핀 연방을 창설함으로써 10년간 독립을 허용했습니다.[115] 케손의 우선순위는 국방, 사회 정의, 불평등, 경제적 다양화, 국가적 성격이었습니다.[74]: 1081, 1117 필리핀어(타갈로그어의 표준화된 품종)가 공용어가 되었고,[116]: 27–29 여성의 참정권이 도입되었으며,[117][57]: 416 토지개혁이 고려되었습니다.[118][119][120]

1941년 12월, 제2차 세계 대전 중에 일본 제국이 필리핀을 침략했고,[121] 호세 P. 로렐에 의해 통치되는 괴뢰 국가로서 필리핀 제2공화국이 세워졌습니다.[122][123] 1942년부터 필리핀 일본 점령은 대규모 지하 게릴라 활동으로 반대했습니다. 전쟁 기간 동안 바타안 사망 행진과 마닐라 학살을 포함하여 잔혹 행위와 전쟁 범죄가 자행되었습니다.[127][128] 1945년 연합군은 일본을 물리쳤고, 전쟁이 끝날 무렵까지 백만 명이 넘는 필리핀인들이 사망한 것으로 추정됩니다.[129][130] 1945년 10월 11일, 필리핀은 유엔의 창립 회원국이 되었습니다.[131][132]: 38–41 1946년 7월 4일, Manuel Roxas의 대통령 재임 기간 동안, 미국은 마닐라 조약으로 이 나라의 독립을 인정했습니다.[132]: 38–41 [133]

독립 (1946–현재)

전후 재건과 후크발라합 반란 종식을 위한 노력은 라몬 막사이 대통령 재임 기간 동안 성공했지만,[134] 산발적인 공산주의자들의 반란은 그 이후에도 계속해서 불붙었습니다.[135] 막사이세이의 후계자 카를로스 P. 가르시아, 정부는 필리핀 소유의 사업을 촉진하는 필리핀 퍼스트 정책을 시작했습니다.[67]: 182 가르시아의 뒤를 이어 디오스다도 마카파갈은 에밀리오 아기날도의 선언일인 7월 4일에서 6월 12일로 독립기념일을 옮겨 [136]북보르네오 동부의 영유권을 주장했습니다.[137][138]

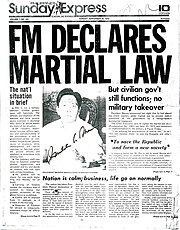

1965년, 마카파갈은 페르디난드 마르코스에게 대통령 선거에서 패배했습니다. 대통령 임기 초기에 마르코스는 주로 외국 대출로 자금을 조달하는 인프라 프로젝트를 시작했습니다. 이는 경제를 개선시켰고 1969년 재선에 기여했습니다.[139]: 58 [140] 마르코스는 1972년[141] 9월 21일 공산주의의[142][143][144] 망령을 이용해 계엄령을 선포하고 법령으로 통치하기 시작했으며,[145] 이 기간은 정치적 탄압, 검열, 인권 침해로 특징지어졌습니다.[146][147] 마르코스의 추종자들이 지배하는 독점 체제는[151] 벌목과 [148][149][150]방송을 포함한 주요 산업에 세워졌고,[57]: 120 설탕 독점 체제는 네그로스 섬의 기근을 초래했습니다.[152] 마르코스는 부인 이멜다와 함께 부패와 수십억 달러의 공적 자금을 횡령한 혐의로 기소되었습니다.[153][154] 마르코스는 대통령 재임 초기에 과도한 차입으로 인해 경제 위기가 발생했으며, 경제가 1984년과 1985년에 매년 7.3%씩 위축된 1980년대 초반의 경기 침체로 인해 악화되었습니다.[155]: 212 [156]

1983년 8월 21일, 야당 지도자 베니그노 아키노 주니어 (마르코스의 주요 경쟁자)가 마닐라 국제 공항의 활주로에서 암살되었습니다.[157] 마르코스는 1986년[158] 대통령 선거를 전격적으로 실시하여 당선자로 선언했지만, 그 결과는 부정적인 것으로 널리 받아들여졌습니다.[159] 결과적인 시위는 마르코스와 그의 동맹국들이 하와이로 도망쳐야 했던 [160][161]피플 파워 혁명으로 이어졌습니다. 아키노의 미망인 코라존이 대통령으로 취임했습니다.[160]

1986년 시작된 민주주의 복귀와 정부 개혁은 국가 부채, 정부 부패, 쿠데타 시도 등으로 인해 차질을 빚었습니다.[163][139]: xii, xiii 모로 분리주의자들과 공산주의자들의[164][165] 반란과 군사적 충돌이 계속되었고,[166] 1991년 6월 피나투보 산이 폭발하는 등 정부도 일련의 재앙에 직면했습니다.[162] 아키노의 뒤를 이어 민영화와 규제완화로 국가경제를 자유화시킨 피델 V. 라모스가 그 뒤를 이었습니다.[167][168] 라모스의 경제적 이득은 1997년 아시아 금융위기의 시작으로 가려졌습니다.[169][170] 그의 후임자인 조셉 에스트라다는 공공 주택을[171] 우선시했지만 2001년 EDSA 혁명으로 인해 그가 전복되고 2001년 1월 20일 부통령 글로리아 마카파갈 아로요가 승계되는 부패 혐의에[172] 직면했습니다.[173] 아로요의 9년 행정부는 경제 성장으로 특징지어졌지만,[11] 2004년 대통령 선거에서 부정선거 의혹을 [174][175]포함한 부패와 정치 스캔들로 얼룩졌습니다.[176] 베니그노 아키노 3세 정부는 좋은 통치와 투명성을 내세우며 경제성장을 지속했습니다.[177]: 1, 3 [178] 아키노 3세는 모로이슬람해방전선(MILF)과 평화협정을 체결하여 방사모로 유기법이 방사모로 자치지역을 설정하는 결과를 낳았지만 마마사파노에서 MILF 반군과의 총격전으로 법 통과가 지연되었습니다.[179][180]

2016년 대통령에 당선된 로드리고 두테르테는 인프라 프로그램과[182][183] 마약 금지 캠페인을[184][185] 시작했는데,[181] 이 프로그램은 마약 확산을[186] 줄였지만 사법 외의 살인으로 이어졌습니다.[187][188] 방사모로 유기농법은 2018년에 제정되었습니다.[189] 2020년 초, 코로나19 팬데믹이 필리핀에 도달했고,[190][191] 국내 총생산은 9.5% 감소하여 1947년 이후 필리핀의 연간 경제 실적 중 최악입니다.[192] 마르코스의 아들 봉봉 마르코스는 2022년 대통령 선거에서 승리했고, 두테르테의 딸 사라는 부통령이 되었습니다.[193]

지리학

필리핀은 약 30만 평방 킬로미터(115,831 평방 마일)의 총 면적([195][196]내륙 수역 포함)을 차지하는 약 7,641개의 섬으로 이루어진 군도입니다.[11][e] 남중국해에서 셀레베스해까지 [198]남북으로 1,850 킬로미터 (1,150 마일)에 걸쳐 뻗어 [199]있는 필리핀은 동쪽으로는 필리핀해,[200][201] 남서쪽으로는 술루해와 접해 있습니다.[202] 이 나라의 11개의 가장 큰 섬은 루손, 민다나오, 사마르, 네그로스, 팔라완, 파나이, 민도로, 레이테, 세부, 보홀, 마스바테이며, 전체 육지 면적의 약 95%입니다.[203] 필리핀의 해안선의 길이는 세계에서 다섯 번째로 긴 36,289 킬로미터(22,549 마일)이며,[204] 필리핀의 배타적 경제수역은 2,263,816 킬로미터2(874,064 평방 마일)입니다.[205]

가장 높은 산은 민다나오의 아포 산으로 해발 2,954 미터 (9,692 피트)의 고도입니다.[11] 필리핀에서 가장 긴 강은 루손 북부에 있는 카가얀 강으로 약 520km(320마일) 동안 흐릅니다.[206] 마닐라의 수도인 마닐라 만은 [207]파시그 강에 의해 라구나 데 만[208](그 나라에서 가장 큰 호수)과 연결되어 있습니다.[209]

필리핀은 태평양 불의 고리 서쪽 가장자리에서 지진과 화산 활동이 빈번합니다.[210]: 4 이 지역은 지진 활동이 활발하며, 여러 방향에서 서로를 향해 수렴하는 판으로 구성되어 있습니다.[211][212] 대부분은 너무 약해서 느낄 수 없지만, 하루에 약 5번의 지진이 기록됩니다.[213] 마지막 대지진은 1976년 모로 만에서, 그리고 1990년 루손에서 일어났습니다.[214] 필리핀에는 23개의 활화산이 있는데, 그 중 메이온, 탈, 캔라온, 불루산 등이 가장 많은 분화를 기록하고 있습니다.[215][8]: 26

이 나라는 복잡한 지질 구조와 높은 수준의 지진 활동의 결과로 귀중한[216] 광물 매장량을 가지고 있습니다.[217][218] 이곳은 세계에서 두 번째로 큰 금 매장량(남아공 다음), 큰 구리 매장량,[219] 그리고 세계에서 가장 큰 팔라듐 매장량을 가지고 있는 것으로 여겨집니다.[220] 다른 미네랄에는 크롬, 니켈, 몰리브덴, 백금, 아연이 포함됩니다.[221] 그러나 열악한 관리 및 법 집행, 토착 커뮤니티의 반대 및 과거 환경 피해로 인해 이러한 자원은 대부분 개발되지 않았습니다.[219][222]

생물다양성

필리핀은 세계에서 가장 높은 발견율과 내생율([224][225]67%)을 보이는 거대한 다양한 국가입니다.[226][227] 필리핀 [228]열대우림에는 약 3,500종의 나무,[231] 8,000종의 꽃이 피는 식물, 1,100종의 양치식물, 998종의[232] 난초 등 다양한 식물이 있습니다.[229][230][233] 필리핀에는 167종의 육상 포유류 (102종의 고유종), 235종의 파충류 (160종의 고유종), 99종의 양서류 (74종의 고유종), 686종의 조류 (224종의 고유종),[234] 20,000종 이상의 곤충이 있습니다.[233]

산호 삼각지대 생태 지역의 중요한 부분으로서,[235][236] 필리핀 해역은 독특하고 다양한 해양 생물과[237] 세계에서 가장 다양한 연안 어류 종을 가지고 있습니다.[238] 이 나라에는 3,200종 이상의 어종(121종 고유종)이 있습니다.[239] 필리핀 해역은 어류, 갑각류, 굴 및 해조류의 재배를 지원합니다.[240][241]

필리핀 전역에는 딥테로카프, 해변 숲,[242] 소나무 숲, 어금니 숲, 낮은 산지 숲, 높은 산지 숲(또는 이끼가 낀 숲), 맹그로브 숲, 극저층 숲 등 8가지 주요 유형의 숲이 분포하고 있습니다.[243] 공식적인 추정에 따르면, 필리핀은 2023년에 7,000,000 헥타르 (27,000 평방 마일)의 숲 덮개를 가지고 있었습니다.[244] 벌목은 미국 식민지 시대에 체계화되어 독립 후 산림전용이 중단되었으며, 마르코스 대통령 재임 기간 동안 규제되지 않은 벌목 양허로 인해 가속화되었습니다. 산림 면적은 1900년 필리핀 전체 국토의 70%에서 1999년 약 18.3%로 감소했습니다.[248] 재활 노력은 미미한 성공을 거두었습니다.[249]

필리핀은 생물 다양성 보존을 위한 우선적인 핫스팟으로,[250][224][251] 2023년[update] 현재 7,790,000 헥타르(30,100 평방 마일)로 확장된 200개 이상의 보호 구역을 가지고 있습니다.[252] 필리핀의 세 곳은 유네스코 세계 문화 유산 목록에 포함되었습니다: 술루 해의 투바타하 산호초,[253] 푸에르토 프린세사 지하 강,[254] 그리고 하미귀탄 산 야생 동물 보호 구역입니다.[255]

기후.

필리핀은 열대성 해양성 기후로 보통 덥고 습합니다. 3월부터 5월까지는 더운 건기, 6월부터 11월까지는 장마, 12월부터 2월까지는 시원한 건기의 세 계절이 있습니다.[256] 남서 몬순(하바갓이라고 함)은 5월부터 10월까지 지속되고, 북동 몬순(아미한)은 11월부터 4월까지 지속됩니다.[257]: 24–25 가장 시원한 달은 1월이고, 가장 따뜻한 달은 5월입니다. 필리핀 전역의 해수면 온도는 위도에 관계없이 동일한 범위에 있습니다. 연평균 기온은 약 26.6°C (79.9°F)이지만 바기오에서는 18.3°C (64.9°F)로 해발 1,500m (4,900ft)입니다.[258] 이 나라의 평균 습도는 82 퍼센트입니다.[257]: 24–25 연간 강우량은 산악 지역인 동해안에서는 5,000 밀리미터(200 인치)에 이르지만, 일부 보호 구역인 계곡에서는 1,000 밀리미터(39 인치) 미만입니다.[256]

필리핀 책임 지역에는 보통 7월부터 10월까지 [259]19개의 태풍이 있으며 [256]그 중 8개 또는 9개가 상륙합니다.[260][261] 필리핀을 강타한 가장 습한 태풍은 1911년 7월 14일부터 18일까지 바기오에 2,210 밀리미터 (87 인치) 떨어졌습니다.[262] 이 나라는 세계에서 기후 변화에 가장 취약한 10개국 중 하나입니다.[263][264]

정부와 정치

필리핀은 민주 정부, 대통령제를 가진 입헌 공화국을 가지고 있습니다.[265] 대통령은 국가 원수이자 정부 수반이며,[266] 군대의 총사령관입니다.[265] 대통령은 6년 임기의 필리핀 국민 직선제로 선출됩니다.[267] 대통령은 내각과 여러 국가 정부 기관 및 기관의 관계자들을 임명하고 대통령을 맡습니다.[268]: 213–214 양원제 의회는 상원(상원, 의원은 6년 임기로 선출)과 하원, 하원으로 구성되며, 의원은 3년 임기로 선출됩니다.[269] 필리핀 정치는 정치적 왕조나 유명인사와 같이 잘 알려진 가문이 지배하는 경향이 있습니다.[270][271]

상원의원은 대규모로 선출되며,[269] 의원은 입법부와 정당 명단에서 선출됩니다.[268]: 162–163 대법원장과 대법관 14명으로 구성된 대법원에 사법 권한이 부여되는데,[272] 대법원장은 사법 변호사위원회가 제출한 지명에서 대통령이 임명합니다.[265]

라모스 정부 이후 연방정부, 단원제, 의회제 정부로 정부를 바꾸려는 시도가 이어졌습니다.[273] 일부 역사학자들은 스페인 식민지 시대의 파드리노 제도 때문에 부패가 심각한 것으로 보고 있습니다.[274][275][276][277][278] 로마 가톨릭교회는 정교 분리에 관한 헌법 조항이 존재하지만, 정치적인 문제에 있어서는 상당한 영향력을 행사하고 있습니다[279].[280]

대외관계

유엔의 창설적이고 활동적인 회원국인 [132]: 37–38 필리핀은 안보리 비상임이사국이었습니다.[281] 이 나라는 특히 동티모르에서 평화유지 활동에 참여합니다.[282][283] 필리핀은 아세안(ASEAN·동남아국가연합)[284][285]의 창립 회원국이자 적극적인 회원국이며, 동아시아 정상회의,[286] G24,[287] 그리고 비동맹운동의 회원국입니다.[288] 이 나라는 2003년부터 이슬람 협력 기구의 옵서버 자격을 얻기 위해 노력해 왔으며,[289][290] SATO의 회원국이었습니다.[291][292] 1천만 명이 넘는 필리핀인들이 200개국에서 생활하고 일하며 [293][294]필리핀에 소프트 파워를 부여하고 있습니다.[155]: 207

1990년대에 필리핀은 외국인 직접 투자를 촉진하기 위해 경제 자유화와 자유 무역을[295]: 7–8 추구하기 시작했습니다.[296] 그것은 세계[295]: 8 무역 기구와 아시아 태평양 경제 협력체의 회원국입니다.[297] 필리핀은 2010년[298] 아세안 상품무역협정, 2023년 역내포괄적경제동반자자유무역협정(FTA)을 체결했습니다.[299][300] 필리핀은 아세안을 통해 중국, 인도, 일본, 한국, 호주, 뉴질랜드와 FTA를 체결했습니다.[295]: 15 이 나라는 일본, 한국 [301]및 유럽 4개국과 양자간 FTA를 체결하고 있습니다. 아이슬란드, 리히텐슈타인, 노르웨이, 스위스.[295]: 9–10, 15

필리핀은 미국과 경제, 안보, 대인관계 등 오랜 관계를 맺고 있습니다.[302] 필리핀의 입지는 미국의 서태평양 도서사슬 전략에서 중요한 역할을 하고 있으며,[303][304] 1951년 양국 간 상호방위조약이 체결되었고, 1999년 방문군협정과 2016년 방위협력 강화협정으로 보완되었습니다.[305] 이 나라는 냉전 기간 동안 미국의 정책을 지지했고 한국과 베트남 전쟁에 참여했습니다.[306][307] 2003년 필리핀은 주요 비 NATO 동맹국으로 지정되었습니다.[308] 두테르테 대통령 하에서 미국과의 관계는 중국과 러시아와의 관계 개선을 위해 약화되었습니다.[309][310][311] 필리핀은 대외 방어를 위해 미국에 크게 의존하고 있고,[177]: 11 미국은 남중국해를 [312]포함한 필리핀을 방어하기 위해 정기적으로 보증을 서 왔습니다.[313]

1975년 이래로 필리핀은 최고의 무역 상대국인[314] 중국과의 관계를 중시해 왔고,[315] 필리핀과 상당한 협력을 해왔습니다.[316][309] 일본은 필리핀에 대한 공적개발원조의 가장 큰 양국간 기여자입니다.[317][318] 비록 제2차 세계대전으로 인해 약간의 긴장이 존재하지만, 많은 적대감은 사라졌습니다.[77]: 93 역사적, 문화적 유대는 스페인과의 관계에 계속 영향을 미치고 있습니다.[319][320] 중동 국가들과의 관계는 그 국가들에서 일하는 필리핀인들의 높은 [321]숫자와 필리핀의 이슬람 소수자들과 관련된 문제들에 의해 형성됩니다;[322] 가정 학대와 전쟁이 그 지역의 약 250만명의 해외 필리핀 노동자들에게 영향을[323] 미치는 것에 대한 우려가 제기되었습니다.[324]

필리핀은 스프래틀리 제도에서 중국, 말레이시아, 대만, 베트남의 영유권과 중복되는 영유권을 가지고 있습니다.[325] 통제되고 있는 섬들 중 가장 큰 섬은 필리핀에서 가장 작은 마을을 포함하고 있는 티투 섬입니다.[326] 2012년 스카버러 숄 대치는 중국이 필리핀으로부터 숄을 압류한 후 국제 중재 사건으로[327] 이어졌고, 결국 필리핀이 승소했습니다.[328] 중국은 결과를 거부하고 [329]숄을 광범위한 분쟁의 중요한 상징으로 만들었습니다.[330]

군사의

필리핀 의용군(AFP)은 필리핀 공군, 필리핀 육군, 필리핀 해군의 3개 분파로 구성되어 있습니다.[331][332] 민간 보안은 내무부와 지방 정부 산하 필리핀 경찰이 담당합니다.[333] AFP의 총[update] 인력은 2022년 기준 약 280,000명이며, 이 중 현역 군인은 13만 명, 예비군은 10만 명, 준군사조직은 5만 명입니다.[334]

2021년에는 4,090,500,000달러(국내총생산의 1.04%)가 필리핀 군대에 지출되었습니다.[335][336] 필리핀 국방비의 대부분은 공산주의와 무슬림 분리주의 반란과 같은 내부 위협에 대한 작전을 주도하는 필리핀 육군에 사용됩니다. 필리핀의 내부 안보에 대한 선점은 1970년대에 시작된 필리핀 해군의 능력 저하에 기여했습니다.[337] 군[338] 현대화 프로그램은 1995년에 시작되어 2012년에 확장되어 보다 유능한 국방 시스템을 구축했습니다.[339]

필리핀은 오랫동안 지역 반란, 분리주의, 테러에 맞서 투쟁해 왔습니다.[340][341][342] 방사모로의 최대 분리주의 단체인 모로민족해방전선과 모로이슬람해방전선은 각각 1996년과 2014년에 정부와 최종 평화협정을 체결했습니다.[343][344] 아부 사야프와 방사모로 이슬람 자유 투사들과[345] 같은 더 많은 무장 단체들이 특히 술루 군도와[346][347] 마구인다나오에서 몸값을 노리고 외국인들을 납치했지만,[345] 그들의 존재는 줄어들었습니다.[348][349] 필리핀 공산당과 그 군사조직인 신인민군은 1970년대부터 정부를 상대로 게릴라전을 벌여왔으며, 1986년 민주주의가 복귀한 후 군사적, 정치적으로 위축되었지만,[341][350] 정부 관리와 보안군에 대한 매복, 폭격, 암살 등을 감행해 왔습니다.[351]

행정 구역

필리핀은 17개 지역, 82개 지방, 146개 도시, 1,488개 지방 자치체, 42,036개 바랑가이로 나뉩니다.[352] 방사모로 이외의 지역은 행정 편의상 구분이 되어 있습니다.[353] 칼라바르존은 2020년[update] 기준으로 인구가 가장 많은 지역으로, 국가 수도 지역(NCR)이 가장 인구 밀도가 높았습니다.[354]

필리핀은 무슬림 민다나오 방사모로 자치구(BARMM)를 제외하고는 단일 국가입니다.[355] 비록 분권화를 위한 단계들이 있었지만,[356][357] 1991년 법은 일부 권한을 지방 정부에 이양했습니다.[358]

인구통계학

필리핀의 인구는 2020년 5월 1일 기준으로 109,035,343명입니다.[359] 2020년에는 미국 인구의 54%가 도시 지역에 살고 있었습니다.[360] 수도인 마닐라와 케손 시(이 나라에서 가장 인구가 많은 도시)는 메트로 마닐라에 있습니다. 필리핀에서 가장 인구가 많은 대도시[361] 지역이자 세계에서 다섯 번째로 [360]인구가 많은 메트로 마닐라에는 약 1,348만 명(필리핀 인구의 12%)이 살고 있습니다.[362] 1948년과 2010년 사이에 필리핀의 인구는 1900만 명에서 9200만 [363]명으로 거의 5배 증가했습니다.

이 나라의 평균 연령은 25.3세이고, 인구의 63.9 퍼센트가 15세에서 64세 사이입니다.[364] 필리핀의 연평균 인구 증가율은 감소하고 있지만,[365] 정부가 인구 증가율을 더 낮추려는 시도는 논란이 되고 있습니다.[366] 이 나라는 1985년[367] 49.2%였던 빈곤율을 2021년 18.1%로 줄였고,[368] 소득 불평등은 2012년부터 줄어들기 시작했습니다.[367]

| 순위 | 이름. | 지역 | 팝. | 순위 | 이름. | 지역 | 팝. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

케손 시  마닐라 | 1 | 케손 시 | 내셔널 캐피털 리전 | 2,960,048 | 11 | 발렌주엘라 | 내셔널 캐피털 리전 | 714,978 |  다바오 시  칼루칸 |

| 2 | 마닐라 | 내셔널 캐피털 리전 | 1,846,513 | 12 | 다스마리냐스 | 칼라바르손 | 703,141 | ||

| 3 | 다바오 시 | 다바오 주 | 1,776,949 | 13 | 산토스 장군 | Soccsksargen | 697,315 | ||

| 4 | 칼루칸 | 내셔널 캐피털 리전 | 1,661,584 | 14 | 파라냐크 | 내셔널 캐피털 리전 | 689,992 | ||

| 5 | 잠보앙가 시 | 잠보앙가 반도 | 977,234 | 15 | 바쿠어 | 칼라바르손 | 664,625 | ||

| 6 | 세부시 | 중앙비사야스 | 964,169 | 16 | 산호세 델 몬테 | 센트럴 루손 | 651,813 | ||

| 7 | 안티폴로 | 칼라바르손 | 887,399 | 17 | 마카티 | 내셔널 캐피털 리전 | 629,616 | ||

| 8 | 타귀그 | 내셔널 캐피털 리전 | 886,722 | 18 | 라스피냐스 | 내셔널 캐피털 리전 | 606,293 | ||

| 9 | 파시그 | 내셔널 캐피털 리전 | 803,159 | 19 | 바콜로드 | 서부 비사야스 주 | 600,783 | ||

| 10 | Cagayan de Oro | 북민다나오 | 728,402 | 20 | Muntinlupa | 내셔널 캐피털 리전 | 543,445 | ||

민족성

이 나라는 외국의 영향과 바다와 지형에 의한 군도의 구분으로 인해 상당한 민족적 다양성을 가지고 있습니다.[266] 2010년 인구 조사에 따르면, 필리핀의 가장 큰 민족은 타갈로그인 (24.4%), 비사야인 [세부야노, 힐리가이논, 와라이족 제외] (11.4%), 세부야노 (9.9%), 일로카노 (8.8%), 힐리가이논 (8.4%), 비콜 (6.8%), 와라이 (4%)였습니다.[11][369] 2010년 기준, 이 나라의 토착민들은 총 1,400만에서 1,700만 명의 인구를 가진 110개의 토착 집단으로 구성되어 있습니다.[370] 이들은 이고로트족, 루마드족, 망얀족, 그리고 팔라완의 토착민들을 포함합니다.[371]

네그리토스는 이 섬의 초기 거주민 중 한 명으로 여겨집니다.[77]: 35 이 소수 원주민 정착민들은 아마도 나중에 이주의 물결에 의해 실향민이 된 아프리카에서 호주로 인류가 처음 이주한 잔해인 호주의 집단입니다.[372] 어떤 필리핀 네그리토들은 그들의 게놈에 데니소반 혼합물을 가지고 있습니다.[373][374] 필리핀계 민족은 일반적으로 여러 동남아시아 민족에 속하며, 언어학적으로는 말레이폴리네시아어를 사용하는 오스트로네시아인으로 분류됩니다.[375] 오스트로네시아인들의 기원은 불확실하지만, 대만 원주민들의 친척들은 아마도 그들의 언어를 가지고 와서 그 지역의 기존 인구들과 섞였을 것입니다.[376][377] 루마드족과 사마-바자우족은 동남아시아 본토의 오스트로아시아어족 및 믈라브리어족과 조상적인 친밀감을 가지고 있습니다. 파푸아뉴기니에서 인도네시아 동부와 민다나오로 서쪽으로 확장된 것이 블란족과 상기르어에서 감지되었습니다.[378]

스페인 제국의 다른 곳에서, 특히 스페인 아메리카에서, 이민자들이 필리핀에 도착했습니다.[379][380]: Chpt. 6 [381] 2016년 내셔널 지오그래픽 프로젝트에 따르면 필리핀 군도에 사는 사람들은 53%의 동남아시아와 오세아니아, 36%의 동아시아, 5%의 남유럽, 3%의 남아시아, 그리고 2%의 북미 원주민 (중남미 출신)을 가지고 있다고 합니다.[380]: Chpt. 6 [382]

혼혈 부부의 후손은 메스티조 또는 티소이로 알려져 있는데, 스페인 식민지 시대에는 주로 중국 메스티조(Mestizos de Sangley), 스페인 메스티조(Mestizos de Espa espol) 및 이들의 혼합(tornatrás)으로 구성되었습니다. 현대 중국계 필리핀인들은 필리핀 사회에 잘 통합되어 있습니다.[266][387] 주로 푸젠성 출신 [388]이민자의 후손으로 알려진 미국 식민지 시대(1900년대 초)에 순수한 중국계 필리핀인은 약 135만 명으로 추정되며, 약 2,280만 명(약 20%)의 필리핀인들이 전 식민지, 식민지, 그리고 20세기 중국 이민자 출신의 중국계 혈통을 가지고 있습니다.[389][390] 2023년[update] 현재 거의 30만 명의 미국 시민들이 미국에 살고 있으며,[391] 최대 25만 명의 미국인들이 로스앤젤레스, 마닐라, 올롱가포 등의 도시에 흩어져 있습니다.[392][393] 그[394] 밖의 중요한 비원주민 소수민족으로는 인도인과 아랍인이 있습니다.[395] 일본계 필리핀인으로는 도쿠가와 이에야스 쇼군의 박해를 피해 도망친 기독교인(기리시탄)이 있습니다.[396]

언어들

186개의 언어가 필리핀을 위해 나열되어 있는데, 그 중 182개의 언어가 살아있는 언어이며, 나머지 4개의 언어에는 더 이상 사용자가 없습니다. 대부분의 토착어들은 오스트로네시아어족의 한 분파인 말레이폴리네시아어족의 필리핀 분파에 속합니다.[375] 차바카노라고 통칭되는 스페인 기반 크리올 품종도 사용됩니다.[397] 많은 필리핀 네그리토어들은 오스트로네시아 문화권의 적응 속에서도 살아남은 독특한 어휘들을 가지고 있습니다.[398]

필리핀어와 영어는 이 나라의 공용어입니다.[5] 타갈로그어의 표준화된 버전인 필리핀어는 주로 메트로 마닐라에서 사용됩니다.[399] 필리핀어와 영어는 정부, 교육, 인쇄, 방송 매체 및 비즈니스에서 사용되며, 종종 제3의 현지어와 함께 사용됩니다.[400] 영어와 다른 현지어(특히 타갈로그어) 간의 코드 전환은 일반적입니다.[401] 필리핀 헌법은 스페인어와 아랍어를 임의 선택적으로 규정하고 있습니다.[5] 19세기 후반에 널리 사용된 언어 프랑카인 스페인어는 사용이 크게 감소했지만,[402][403] 스페인어 외래어는 여전히 필리핀 언어에 존재합니다.[404][405][406] 아랍어는 주로 민다나오 이슬람 학교에서 가르칩니다.[407]

2020년[update] 기준 국내에서 일반적으로 사용되는 상위 언어는 타갈로그어, 비니사야어, 힐리가이논어, 일로카노어, 세부아노어, 비콜어입니다.[408] 19개의 지역 언어는 교육 매체로서 보조 공용어입니다.[4]

쿠요논어, 이푸가오어, 잇바야트어, 칼링가어, 카마요어, 칸카나이어, 마스바테뇨어, 롬블로마논어, 마노보어, 그리고 몇몇 비사야어를 포함한 다른 토착어들이 그들의 지방에서 사용됩니다.[375] 필리핀 수화는 국가 수화이자 청각장애 교육의 언어입니다.[409]

종교

필리핀은 종교의 자유가 있는 세속적인 국가임에도 불구하고 압도적인 다수의 필리핀인들이 종교를[410] 매우 중요하게 생각하고 있으며 비종교는 매우 낮습니다.[411][412][413] 기독교가 지배적인 종교이며,[414][415] 인구의 약 89퍼센트가 그 뒤를 이룹니다.[416] 이 나라는 2013년[update] 기준으로 세계에서 세 번째로 많은 로마 가톨릭 신자들을 보유하고 있으며, 아시아에서 가장 큰 기독교 국가였습니다.[417] 2020년 인구 조사 자료에 따르면 인구의 78.8%가 로마 가톨릭을 믿었고, 다른 기독교 교파들은 이글레시아니크리스토, 필리핀 독립 교회, 7일간의 재림주의를 포함합니다.[418] 2010년에는 개신교 신자가 인구의 약 5%에서 7%를 차지했습니다.[419][420] 필리핀은 전 세계에 많은 기독교 선교사들을 파견하고 있으며, 외국인 사제와 수녀들을 위한 연수원입니다.[421][422]

이슬람교는 2020년 인구 조사에서 인구의 6.4%가 이슬람교에서 두 번째로 큰 종교입니다.[418] 대부분의 이슬람교도들은 민다나오와 인근 섬에 살고 있으며,[415] 대부분은 수니파 이슬람교의 샤피이 학파를 고수하고 있습니다.[423]

인구의 약 0.2%가 토착 종교를 따르고 있으며,[418] 이 종교의 관습과 민간 신앙은 종종 기독교와 이슬람교와 혼합되어 있습니다.[210]: 29–30 [424] 중국계 필리핀인을 중심으로 [418]인구의 약 0.04%가 불교를 믿고 있습니다.[425]

헬스

필리핀의 의료 서비스는 국가 및 지방 정부가 제공하지만, 민간 지불이 대부분의 의료 지출을 차지합니다.[426]: 25–27 [427] 2022년 1인당 보건 지출은 10,059.49 ₱이고 보건 지출은 국가 GDP의 5.5%였습니다. 2023년 보건 의료 예산 배분액은 ₱3,349억 원이었습니다. 두테르테 대통령의 2019년 보편적 의료법 제정으로 모든 필리핀인이 국가 건강보험 프로그램에 자동으로 가입할 수 있게 되었습니다.[430][431] 2018년부터 정부가 운영하는 여러 병원에 말라사킷 센터(원스톱숍)를 설치하여 불우 환자에게 의료 및 재정 지원을 하고 있습니다.[432]

2023년[update] 기준 필리핀의 평균 기대수명은 70.48세(남성 66.97세, 여성 74.15세)입니다.[11] 필리핀인들의 제네릭 의약품 수용 증가로 의약품에 대한 접근성이 향상되었습니다.[426]: 58 2021년 국가의 주요 사망 원인은 허혈성 심장 질환, 뇌혈관 질환, COVID-19, 신생물, 당뇨병이었습니다.[433] 전염성 질병은 주로 홍수와 같은 자연 재해와 관련이 있습니다.[434]

필리핀에는 1,387개의 병원이 있으며, 그 중 33%는 정부가 운영하는 병원입니다. 23,281개의 바랑가이 보건소, 2,592개의 농촌 보건소, 2,411개의 출산 가정, 659개의 의무실이 전국적으로 1차 진료를 제공합니다.[435] 1967년 이래로 필리핀은 세계 최대 간호사 공급국이 되었고,[436] 간호 졸업생의 70%가 해외로 일하러 나가 숙련된 실무자를 유지하는 데 문제가 생겼습니다.[437]

교육

필리핀의 초중등 교육은 초등학교 6년, 중학교 4년, 고등학교 2년으로 구성되어 있습니다.[439] 정부가 제공하는 공교육은 초등학교와 중등학교 그리고 대부분의 공립 고등교육기관에서는 무료입니다.[440][441] 재능 있는 학생들을 위한 과학 고등학교는 1963년에 설립되었습니다.[442] 정부는 기술 교육 및 기술 개발 기관을 통해 기술-직업 훈련 및 개발을 제공합니다.[443] 2004년, 정부는 문해력을 향상시키기 위해 학교 밖의 아이들, 청소년들, 그리고 어른들에게 대안적인 교육을 제공하기 [444][445]시작했습니다; 마다리스는 그 해 16개의 지역, 주로 교육부 산하의 민다나오 무슬림 지역에서 주류를 이루었습니다.[446]

필리핀에는 2019년[update] 기준 1,975개의 고등교육기관이 있으며, 이 중 246개가 공립이고 1,729개가 사립입니다.[447] 공립 대학은 비종파적이며, 주로 국가가 운영하는 대학 또는 지방 정부가 지원하는 대학으로 분류됩니다.[448][449] 국립 대학은 8개 학교로 구성된 필리핀 대학(UP) 시스템입니다.[450] 이 나라에서 가장 높은 순위를 차지한 대학은 UP, 아테네오 데 마닐라 대학, 데 라 살레 대학, 그리고 산토 토마스 대학입니다.[451][452][453]

2019년[update] 필리핀의 기본 문맹률은 5세 이상 93.8%, [454]기능 문맹률은 10세 이상 64세 미만 91.6%였습니다.[455] 국가 예산의 상당 부분을 차지하는 교육은 ₱ 5조 2680억 2023년 예산에서 9009억 ₱가 배정되었습니다. 필리핀에는[update] 2023년 현재 1,640개의 필리핀 국립도서관이 소속되어 있습니다.[456]

경제.

필리핀 경제는 세계에서 34번째로 크고 2023년[update] 명목 국내총생산은 4,357억 달러로 추정됩니다.[13] 새롭게 산업화된 국가로서 필리핀 [457][458]경제는 농업 기반에서 서비스와 제조업에 더 중점을 두고 있습니다.[457][459] 이 나라의 노동력은 2022년[update] 현재 약 4900만 명이며 실업률은 4.3%입니다.[460] 총 국제 준비금은 2023년[update] 4월 기준 총 1억 761만 달러입니다.[461] GDP 대비 부채 비율은 그해 3분기 말 17년 만에 최고치인 63.7%에서 2022년 말 60.9%로 감소했으며 코로나19 팬데믹 기간 동안 회복력을 나타냈습니다.[462] 필리핀의 통화 단위는 ₱ 또는 PHP입니다.

필리핀은 순수 수입국이자 [295]: 55–56, 61–65, 77, 83, 111 [466]채무국입니다.[467] 2020년[update] 기준 주요 수출시장은 중국, 미국, 일본, 홍콩, 싱가포르이며,[468] 주요 수출품목은 집적회로, 사무용 기계 및 부품, 전기변압기, 절연배선, 반도체 등입니다.[468] 그해 주요 수입 시장은 중국, 일본, 한국, 미국 및 인도네시아였습니다.[468] 주요 수출 작물은 코코넛, 바나나, 파인애플을 포함합니다; 그것은 세계 최대의 아바카 생산국이고,[8]: 226–242 2022년에는 세계 2위의 니켈 광석 수출국이었고,[469] 금박 금속의 최대 수출국이자 2020년에는 코프라의 최대 수입국이었습니다.[468]

필리핀은 2010년경부터 연평균 6~7%의 성장률을 보이며 세계에서 가장 빠르게 성장하는 경제국 중 하나로 부상했습니다.[470][471] 그러나 마닐라(특히)가 새로운 경제 성장의 대부분을 차지하면서 지역 발전은 불균등합니다.[472][473] 해외 필리핀인들의 송금액은 2022년 국내총생산(GDP)의 8.9%를 차지하며 사상 최대인 361억4000만 달러를 기록했습니다.[474][471][475] 필리핀은 세계의 주요 비즈니스 프로세스 아웃소싱(BPO) 센터입니다.[476][477] 약 130만 명의 필리핀인들이 주로 고객 서비스 분야인 BPO 분야에서 일하고 있습니다.[478]

과학기술

필리핀은 농업 연구와 개발에 대한 지출이 상대적으로 적음에도 불구하고 아시아에서 가장 큰 농업 연구 시스템 중 하나입니다.[479][480] 이 나라는 쌀,[481][482] 코코넛,[483] 바나나를 포함한 새로운 품종의 농작물을 개발했습니다.[484] 연구 기관으로는 필리핀 쌀 연구소와[485] 국제 쌀 연구소가 있습니다.[486]

필리핀 우주국은 필리핀의 우주 프로그램을 유지하고 있으며,[487][488] 필리핀은 1996년에 첫 번째 위성을 구입했습니다.[489] 첫 번째 마이크로 위성인 디와타-1은 2016년 미국 시그너스 우주선에서 발사되었습니다.[490]

필리핀은 휴대전화 사용자의 집중도가 [491]높고 모바일 상거래 수준이 높습니다.[492] 문자 메시지는 대중적인 의사소통 수단이며, 2007년에 우리나라는 하루에 평균 10억 개의 문자 메시지를 보냈습니다.[493] 필리핀 통신 산업은 20년 이상 PLDT-Globe Telecom duopoly에 의해 지배되어 왔으며,[494] 2021년 Dito Telecommunity의 진입으로 필리핀의 통신 서비스가 개선되었습니다.[495]

관광업

필리핀은 기후와 생활비가 저렴하기 때문에 외국인들에게 인기 있는 은퇴 목적지입니다.[496] 필리핀은 또한 다이빙 애호가들에게 최고의 목적지이기도 합니다.[497][498] 관광지로는 2012년 여행+레저로 세계 최고의 섬이라 불리는 보라카이,[499] 팔라완의 코론과 엘니도, 세부, 시아르가오, 보홀 등이 있습니다.[500]

관광업은 2021년 필리핀 국내총생산(GDP)에서 5.2%(코로나19 팬데믹 이전인 2019년 12.7%보다 낮음)[501]를 기여했고, 2019년에는 570만 개의 일자리를 제공했습니다.[502] 필리핀은 2023년에 545만 명의 해외 관광객을 유치했는데, 이는 팬데믹 이전인 2019년의 826만 명 기록보다 30% 낮은 수치입니다; 대부분의 관광객들은 한국(26.4%), 미국(16.5%), 일본(5.6%), 호주(4.89%), 중국(4.84%)에서 왔습니다.[503]

사회 기반 시설

교통.

필리핀의 교통은 도로, 항공, 철도, 수상입니다. 도로는 98퍼센트의 사람과 58퍼센트의 화물을 운반하는 지배적인 운송 수단입니다.[505] 2018년 12월 전국 도로는 210,528킬로미터(130,816마일)였습니다.[506] 이 나라의 육상 교통의 중추는 루손 섬, 사마르 섬, 레이테 섬, 민다나오 섬을 연결하는 범필리핀 고속도로입니다.[507] 섬간 교통은 17개 도시를 연결하는 고속도로와 페리 노선의 통합된 집합인 919 킬로미터(571 마일)의 강한 공화국 해상 고속도로에 의해 이루어집니다.[508][509] 지프니는 대중적이고 상징적인 공공 공공 차량이며,[8]: 496–497 다른 공공 토지 교통에는 버스, UV 익스프레스, 필캡, 택시 및 세발자전거가 포함됩니다.[510][511] 교통은 마닐라와 수도로 가는 간선 도로에서 중요한 문제입니다.[512][513]

역사적으로 [514]더 광범위하게 사용되었음에도 불구하고 필리핀의 철도 교통은 메트로 마닐라와 라구나[515] 주, 케손 주 내에서 승객을 수송하는 데 제한되어[8]: 491 있으며,[516] 비콜 지역의 짧은 선로가 있습니다.[8]: 491 이 나라는 2019년[update] 기준으로 겨우 79킬로미터(49마일)의 철도 발자국을 가지고 있었는데, 이는 244킬로미터(152마일)로 확장할 계획이었습니다.[517] 도로 정체를 줄이기 위해 화물 철도의 부활이 계획되어 있습니다.[518][519]

필리핀에는 2022년[update] 기준으로 90개의 국가 정부 소유 공항이 있으며, 이 중 8개 공항이 국제 공항입니다.[520] 과거 마닐라 국제공항으로 알려졌던 니노이 아키노 국제공항이 가장 많은 승객을 보유하고 있습니다.[520] 2017년 항공 국내 시장은 필리핀 국적 항공사이자 아시아에서 가장 오래된 상업 항공사인 필리핀 항공과 [521][522]세부 퍼시픽(국내 대표 저비용 항공사)이 장악했습니다.[523][524]

필리핀 전역에는 다양한 보트가 사용되고 [525]있으며 대부분은 방카[526] 또는 방카로 알려진 이중 아웃트리거 선박입니다.[527] 현대의 배들은 통나무 대신 합판을 사용하고, 돛 대신에 모터 엔진을 사용합니다;[526] 그것들은 낚시와 섬간 여행을 위해 사용됩니다.[527] 필리핀에는 1,800개 이상의 항구가 있으며,[528] 이 중 마닐라(국가의 주요 항구이자 가장 붐비는 항구),[529] 바탄가스, 수빅만, 세부, 일로일로, 다바오, 카가얀 데 오로, 제너럴 산토스, 잠보앙가 등이 아세안 교통 네트워크의 일부입니다.[530][531]

에너지

필리핀의 총 설치 전력 용량은 2021년 기준 26,882MW로 43%는 석탄, 14%는 석유, 14%는 수력, 12%는 천연가스, 7%는 지열원에서 생산됩니다.[532] 미국과 인도네시아에 이어 세계에서 세 번째로 큰 지열 에너지 생산국입니다.[533] 이 나라에서 가장 큰 댐은 팡가시난의 아그노 강에 있는 길이 1.2 킬로미터의 산 로케 댐입니다.[534] 1990년대 초 팔라완 해안에서 발견된 말람파야 가스전은 필리핀의 수입 석유 의존도를 낮췄습니다; 그것은 루손의 에너지 요구량의 약 40%와 국가 에너지 요구량의 30%를 제공합니다.[8]: 347 [535]

필리핀에는 루손, 비사야스, 민다나오에 각각 하나씩 3개의 전력망이 있습니다.[536] 필리핀 국가 그리드 공사는 2009년부터[537] 필리핀의 전력망을 관리하고 있으며, 섬 전역에 간접 송전선을 제공하고 있습니다. 소비자에 대한 전기 분배는 개인 소유의 배전 유틸리티와 정부 소유의 전기 협동조합에 의해 제공됩니다.[536] 필리핀의 가정용 전력화 수준은 2021년 말 기준 약 95.41%[538]입니다.

원자력 에너지를 활용하기 위한 계획은 1973년 석유 위기에 대응하여 페르디난드 마르코스 대통령 재임 기간인 1970년대 초에 시작되었습니다.[539] 필리핀은 1984년 바타안에 동남아시아 최초의 원자력 발전소를 완공했습니다.[540] 1986년 체르노빌 참사 이후 마르코스의 퇴진 이후 정치적 문제와 안전에 대한 우려로 인해 발전소의 가동이 중단되었으며,[541][539] 운영 계획은 여전히 논란의 여지가 있습니다.[540][542]

수도 및 위생

메트로 마닐라 외곽의 상수도와 위생 시설은 정부가 도시나 마을의 지역 수역을 통해 제공합니다.[543][544][545] 메트로 마닐라는 마닐라 워터와 메이닐라드 워터 서비스가 제공합니다. 국내용 얕은 우물을 제외한 지하수 이용자는 국가수자원위원회의 허가를 받아야 합니다.[544] 2022년 총 출수량은 2021년 890억 입방미터3.1×10^ 컷)에서 910억 입방미터(3.2×10 컷)로 증가했고, 물에 대한 총 지출액은 ₱ 1,448억 1,000만 명에 달했습니다.

필리핀의 대부분의 하수는 정화조로 흘러갑니다.[544] 2015년 상수도 및 위생을 위한 공동 모니터링 프로그램은 필리핀 인구의 74%가 위생 개선에 접근할 수 있으며 1990년에서 2015년 사이에 "좋은 진전"이 이루어졌다고 지적했습니다.[547] 2016년[update] 기준 필리핀 가정의 96%가 개선된 식수 공급원을 가지고 있고 92%의 가정이 위생적인 화장실 시설을 가지고 있습니다. 그러나 특히 농촌 및 도시 빈곤 지역 사회에서 적절한 하수도 시스템에 대한 화장실 시설의 연결은 크게 부족합니다.[426]: 46

문화

필리핀은 파편화된 지리로 인해 강화된 상당한 문화적 다양성을 가지고 있습니다.[42]: 61 [548] 오랜 식민지화의 결과로 스페인과 미국 문화는 필리핀 문화에 지대한 영향을 미쳤습니다.[549][266] 민다나오와 술루 군도의 문화는 스페인의 영향력이 제한적이고 인근 이슬람 지역의 영향력이 더 컸기 때문에 뚜렷하게 발전했습니다.[49]: 503 이고로족과 같은 토착 집단은 스페인에 저항함으로써 그들의 식민지 이전의 관습과 전통을 보존해왔습니다.[550][551] 그러나 19세기 동안 공유된 국가 상징과 문화적, 역사적 터치스톤으로 국가 정체성이 나타났습니다.[548]

히스패닉계의 유산으로는 가톨릭교의[57]: 5 [549] 우세와 스페인식 이름과 성씨의 유행이 있는데, 이는 1849년 칙령이 성씨의 체계적인 보급과 스페인식 이름 붙이기 관습의 시행을 명령한 결과이며,[8]: 75 [56]: 237 많은 지역의 이름도 스페인에서 유래했습니다.[552] 현대 필리핀 문화에[266] 대한 미국의 영향력은 패스트푸드와 미국 영화와 음악의 영국과[553]: 12 필리핀 소비에서 분명히 드러납니다.[549]

필리핀의 공휴일은 일반 공휴일 또는 특별 공휴일로 분류됩니다.[554] 축제는 주로 종교적이며, 대부분의 마을에는 그러한 축제(보통 수호성인을 기리기 위해)가 있습니다.[555][556] 더 잘 알려진 축제는 5월에 열리는 성모 마리아를 위한 한 달 간의 헌신인 아티-아티한,[557] 디나양,[558] 모리오네스,[559] 시눌로그,[560] 플로레스 데 마요를 포함합니다.[561] 이 나라의 크리스마스 시즌은 빠르면 9월 1일부터 시작되며,[562]: 149 홀리 위크는 기독교인들을 위한 엄숙한 종교 의식입니다.[563][562]: 149

가치

필리핀의 가치관은 주로 친족, 의무, 우정, 종교(특히 기독교) 및 상업에 기반을 둔 개인적 동맹에 뿌리를 두고 있습니다.[77]: 41 그들은 파키사마를 통해 사회적 화합을 중심으로 하며,[564]: 74 주로 집단의 수용 욕구에 의해 동기 부여됩니다.[565][566][553]: 47 우탕나루프(감사의 빚)를 통한 호혜성은 필리핀의 중요한 문화적 특성이며, 내면화된 빚은 결코 완전히 상환될 수 없습니다.[564]: 76 [567] 이러한 가치관으로부터의 차이에 대한 주요 제재는 히야(수치)[568]와 아모르 프로피오(자존감)의 상실이라는 개념입니다.[566]

가족은 필리핀 사회의 중심입니다; 충성심, 친밀한 관계 유지, 노부모 돌봄과 같은 규범들이 필리핀 사회에 깊이 뿌리박혀 있습니다.[569][570] 권위와 노인에 대한 존중을 중시하며, 마노와 존칭 포오포와 쿠야(형) 또는 식사(형)와 같은 몸짓으로 보여집니다.[571][572] 다른 필리핀인들의 가치관은 미래에 대한 낙관주의, 현재에 대한 비관주의, 다른 사람들에 대한 걱정, 우정과 친근함, 환대, 종교성, 자신과 다른 사람들에 대한 존중, 그리고 진실성입니다.[573]

예술과 건축

필리핀 예술은 토착 민속 예술과 외국의 영향, 주로 스페인과 미국을 결합합니다.[574][575] 스페인 식민지 시대 동안, 예술은 가톨릭을 전파하고 인종적으로 우월한 집단의 개념을 지지하기 위해 사용되었습니다.[575] 고전적인 그림들은 주로 종교적이었습니다;[576] 스페인 식민지 통치 기간 동안 유명한 예술가들은 후안 루나와 펠릭스 레서레치온 이달고를 포함했고, 그의 작품들은 필리핀에 관심을 끌었습니다.[577] 모더니즘은 1920년대와 1930년대에 Victorio Edades와 Fernando Amorsolo에 의해 필리핀에 소개되었습니다.[578]

전통적인 필리핀 건축은 두 가지 주요 모델을 가지고 있습니다: 토착 바하이 쿠보와 스페인의 지배 아래 발전한 바하이 나바토.[8]: 438–444 바타네스와 같은 일부 지역은 기후에 따라 약간의 차이가 있습니다. 석회암은 건축 자재로 사용되었고, 집은 태풍에 견딜 수 있도록 지어졌습니다.[580][581]

스페인 건축은 중앙 광장이나 광장 시장 주변의 마을 디자인에 각인을 남겼지만, 많은 건물들이 제2차 세계 대전 동안 철거되었습니다.[47] 몇몇 필리핀 교회들은 지진을 견디도록 바로크 건축을 채택하여 지진 바로크의 발전을 이끌었습니다.[582][583] 네 개의 바로크 교회는 유네스코 세계문화유산에 등재되었습니다.[579] 필리핀의 몇몇 지역에 있는 스페인 식민지 요새(Fuerzas)는 주로 선교 건축가들에 의해 설계되었고 필리핀 석공들에 의해 지어졌습니다.[584] 일로코스 수르에 있는 비간은 히스패닉 스타일의 집과 건물로 유명합니다.[585]

미국의 통치는 정부 건물과 아르데코 극장의 건설에 새로운 건축 양식을 도입했습니다.[586] 미국 시대에 건축 디자인과 다니엘 버넘의 마스터 플랜을 사용한 도시 계획이 마닐라와 바기오의 일부에서 이루어졌습니다.[587][588] 버넘 계획의 일부는 그리스나 신고전주의 건축물을 연상시키는 정부 건물의 건설이었습니다.[586][583] 스페인과 미국 시대의 건물들은 Iloilo, 특히 Calle Real에서 볼 수 있습니다.[589]

음악과 무용

필리핀 민속 무용에는 전통적인 토착의 영향과 스페인의 영향에서 비롯된 두 가지 유형이 있습니다.[210]: 173 비록 토종 춤이 덜 대중화되었지만,[591]: 77 민속 춤은 1920년대에 부활하기 시작했습니다.[591]: 82 히스패닉계 필리핀 춤인 카리뇨사는 비공식적으로 이 나라의 국민 춤으로 여겨집니다.[592] 인기 있는 토착 춤에는 대나무 장대의 리드미컬한 박수 소리를 포함하는 티니클링과 싱길이 있습니다.[593][594] 섬세한 발레부터 거리 중심의[595] 브레이크 댄스까지 현대무용은 다양합니다.[596][597]

전통적인 만돌린 형태의 악기가 있는 론달리아 음악은 스페인 시대에 인기가 있었습니다.[155]: 327 [598] 스페인의 영향을 받은 음악가들은 주로 14현 기타가 있는 반두리아 기반 밴드입니다.[599][598] 쿤디만은 1920년대와 1930년대에 발전했습니다.[600] 미국 식민지 시대는 많은 필리핀 사람들이 미국 문화와 대중 음악을 접하게 했습니다.[600] 록 음악은 1960년대에 필리핀 사람들에게 소개되었고 팝 록, 얼터너티브 록, 헤비 메탈, 펑크, 뉴 웨이브, 스카, 레게를 포괄하는 용어인 필리핀 록(또는 피노이 록)으로 발전했습니다. 1970년대 계엄령은 필리핀 포크 록 밴드와 정치 시위의 선두에 섰던 예술가들을 배출했습니다.[601]: 38–41 이 10년은 또한 마닐라 사운드와 오리지널 필리핀 음악(OPM)[602][56]: 171 의 탄생을 목격했습니다. 1979년에 시작된 필리핀 힙합은 1990년에 주류에 진입했습니다.[603][601]: 38–41 노래방도 인기가 많습니다.[604] 2010년부터 2020년까지 Pinoy pop(피팝)은 K-pop과 J-pop의 영향을 받았습니다.[605]

지역에서 제작된 연극 드라마는 1870년대 후반에 설립되었습니다. 그 무렵 스페인의 영향으로 자르주엘라 연극(음악과 함께)[606]과 춤과 함께 희극이 소개되었습니다. 연극은 전국적으로 인기를 끌었고,[591]: 69–70 여러 지역 언어로 쓰여졌습니다.[606] 미국의 영향으로 보드빌과 발레가 등장했습니다.[591]: 69–70 현실적인 연극은 20세기 동안 지배적이 되었고, 연극은 동시대의 정치적, 사회적 문제에 초점을 맞추게 되었습니다.[606]

문학.

필리핀 문학은 일반적으로 필리핀어, 스페인어 또는 영어로 쓰여진 작품으로 구성됩니다. 가장 초기의 잘 알려진 작품들 중 일부는 17세기에서 19세기 사이에 만들어졌습니다.[607] 그 중에는 이름을 딴 마법의 새에 관한 서사시인 '이봉 아다르나'[608]와 타갈로그 작가 프란시스코 발라그타스의 '로라의 플로란테'가 포함되어 있습니다.[609][610] 호세 리잘은 스페인 식민지 지배의 부당함을 묘사한 소설 Noli Me Tangere (사회적 암)와 El filibusterismo (욕망의 통치)를 썼습니다.[611][612]

민속 문학은 19세기까지만 해도 스페인의 무관심으로 식민지의 영향을 비교적 받지 않았습니다. 스페인 식민지 시대에 인쇄된 문학 작품들은 대부분 종교적 성격을 띠었지만, 나중에 스페인어를 배운 필리핀 엘리트들은 민족주의 문학을 썼습니다.[210]: 59–62 미국의 도착은 필리핀의 문학적인 영어[210]: 65–66 사용을 시작했고 1920년대부터 1970년대까지 번창한 필리핀 만화 산업의 발전에 영향을 미쳤습니다.[613][614] 1960년대 후반, 페르디난드 마르코스의 대통령 재임 기간 동안, 필리핀 문학은 정치적 행동주의의 영향을 받았습니다; 많은 시인들은 타갈로그를 사용하기 시작했습니다.[210]: 69–71

필리핀 신화는 주로 구전을 통해 전해져 내려오고 있는데,[615] 유명한 인물들은 마리아 마킬링,[616] 람앙,[617] 사리마녹입니다.[210]: 61 [618] 이 나라에는 많은 민속 서사시가 있습니다.[619] 부유한 가족들은 특히 민다나오에서 서사시의 필사본을 가보로 보존할 수 있었습니다. 마라나오어 다랑겐어가 그 예입니다.[620]

미디어

필리핀 미디어는 주로 필리핀어와 영어를 사용하지만 방송은 필리핀어로 전환되었습니다.[400] 텔레비전 쇼, 광고 및 영화는 영화 및 텔레비전 심사 분류 위원회의 규제를 받습니다.[621][622] 대부분의 필리핀 사람들은 텔레비전, 인터넷,[623] 소셜 미디어에서 뉴스와 정보를 얻습니다.[624] 이 나라의 대표적인 국영 방송 텔레비전 네트워크는 인민 텔레비전 네트워크(PTV)입니다.[625] 2020년 5월 ABS-CBN 가맹점이 만료되기 전에는 ABS-CBN과 GMA가 지배적인 TV 네트워크였습니다.[626][627] 텔레세리즈로 알려져 있고 주로 ABS-CBN과 GMA가 제작하는 필리핀 텔레비전 드라마는 다른 여러 나라에서도 볼 수 있습니다.[628][629]

현지 영화 제작은 1919년 호세 네포무세노 감독의 첫 필리핀 제작 장편 영화 달라강 부키드(Dalagang Bukid, 시골에서 온 소녀)의 개봉과 함께 시작되었습니다.[112][113]: 8 무성 영화 시대에는 제작사들이 소규모로 남아있었지만 1933년에는 음향 영화와 더 큰 규모의 제작물들이 등장했습니다. 전후 1940년대에서 1960년대 초반은 필리핀 영화의 중요한 시기로 여겨집니다. 상업 영화 산업이 1980년대까지 확대되었지만, 1962-1971년 10년은 양질의 영화가 감소했습니다.[112] 비평가들의 극찬을 받은 필리핀 영화로는 1982년 개봉한 히말라(기적)와 오로, 플라타, 마타(금, 은, 죽음)가 있습니다.[630][631] 21세기가 된 이래로, 이 나라의 영화 산업은 더 많은 예산을 들인 외국 영화들[632](특히 할리우드 영화들)과 경쟁하기 위해 고군분투해왔습니다.[633][634] 그러나 예술 영화는 번창했고, 몇몇 독립 영화들은 국내외에서 성공을 거두었습니다.[635][636][637]

필리핀에는 많은 수의 라디오 방송국과 신문이 있습니다.[626] 영어 브로드시트는 임원, 전문가 및 학생들 사이에서 인기가 있습니다.[116]: 233–251 1990년대에 성장한 저렴한 타갈로그 타블로이드 신문은 (특히 마닐라에서)[638] 인기가 있지만, 온라인 뉴스를 선호하는 신문 독자층은 전반적으로 감소하고 있습니다.[624][639] 전국적인 독자 수와 신뢰도를 기준으로 상위 [116]: 233 3개 신문은 필리핀 일간 인콰이어러, 마닐라 회보, 필리핀 스타입니다.[640][641] 비록 언론의 자유는 헌법에 의해 보호되지만,[642] 이 나라는 13명의 미해결 언론인 살인 사건으로 인해 2022년 언론인 보호 위원회에 의해 언론인에게 가장 위험한 나라 7위로 선정되었습니다.[643]

필리핀 인구는 세계 최고의 인터넷 사용자입니다.[644] 2021년 초 필리핀인의 67%(7391만 명)가 인터넷에 접속했고, 압도적으로 많은 수가 스마트폰을 사용했습니다.[645] 필리핀은 2023년 글로벌 혁신지수 56위를 [646]기록해 2014년 100위에서 상승했습니다.[647]

요리.

말레이폴리네시아에서 유래된 필리핀 전통 요리는 16세기부터 발전해 왔습니다. 그것은 주로 필리핀 미각에 맞춘 히스패닉, 중국 및 미국 요리의 영향을 받았습니다.[648][649] 필리핀 사람들은 단맛, 짠맛, 신맛 조합을 중심으로 [650]한 강력한 맛을 선호하는 경향이 있습니다.[651]: 88 쌀은 일반적인 주식[652] 전분이지만 카사바는 민다나오의 일부 지역에서 더 흔합니다.[653][654] 아도보는 비공식 국가 요리입니다.[655] 다른 인기 있는 요리로는 레콘, 카레, 시니강,[656] 판싯, 란치아, 아로즈 칼도가 있습니다.[657][658][659] 전통 디저트는 푸토, 수만, 비빙카가 포함된 카카닌(떡)입니다.[660][661] 깔라만시,[662] 우베,[663] 필리 등의 재료가 필리핀 디저트에 사용됩니다.[664][665] 파티, 바궁, 도요 등의 조미료를 아낌없이 사용하여 필리핀 특유의 풍미를 선사합니다.[657][651]: 73

다른 동아시아나 동남아시아 국가들과 달리, 대부분의 필리핀 사람들은 젓가락으로 먹지 않고 숟가락과 포크를 사용합니다.[666] 손가락으로[667] 먹는 전통적인 음식(카마얀이라고 알려져 있음)은 도시화가 덜 된 지역에서 사용되었지만,[668]: 266–268, 277 필리핀 음식이 외국인들과 도시 주민들에게 소개되면서 대중화되었습니다.[669][670]

스포츠와 레크리에이션

아마추어와 프로 수준에서 경기되는 농구는 이 나라의 가장 인기 있는 스포츠로 여겨집니다.[671][672] 다른 인기 있는 스포츠로는 Manny Pacquiao와 Efren Reyes의 업적에 힘입어 복싱과 당구가 있습니다.[562]: 142 [673] 국민 무술은 아르니스입니다.[674] 사봉(닭싸움)은 특히 필리핀 남성들 사이에서 인기 있는 오락이며, 마젤란 원정대에 의해 기록되었습니다.[675] 비디오 게임과 e스포츠는 패틴로, 텀방프레소, 룩송티닉, 피코 등 토종 게임의 인기가 젊은 층에서 감소하면서 [676][677]새로운 취미로 떠오르고 있습니다.[678][677] 전통 게임을 보존하고 홍보하기 위한 법안이 여러 건 제출되었습니다.[679]

남자 축구 국가대표팀은 아시안컵에 한 번 참가한 적이 있습니다.[680] 여자 축구 국가대표팀은 2022년 1월 첫 월드컵인 2023년 FIFA 여자 월드컵 출전권을 획득했습니다.[681] 필리핀은 미국 주도의 1980년 하계 올림픽 보이콧을 지지했을 때를 제외하고 1924년부터 모든 하계 올림픽에 참가해 왔습니다.[682][683] 1972년에 첫 선을 보인 이 나라는 동계 올림픽에 참가한 최초의 열대 국가였습니다.[684][685] 2021년 필리핀은 역도선수 히딜린 디아즈의 도쿄 우승으로 사상 첫 올림픽 금메달을 받았습니다.[686]

참고 항목

메모들

- ^ 마닐라는 국가의 수도로 지정되어 있지만, 정부의 소재지는 흔히 "메트로 마닐라"로 알려진 국가 수도 지역이며, 그 중 마닐라 시는 일부입니다.[2][3] 많은 국가 정부 기관들이 마닐라 수도 내에 위치한 말라카냥 궁전과 다른 기관들을 제외하고 마닐라 메트로의 여러 지역에 위치해 있습니다.

- ^ 1987년 헌법에 따르면, "스페인어와 아랍어는 자발적이고 선택적으로 추진되어야 합니다."[5]

- ^ 필리핀의 공인된 지역 언어는 다음과 같습니다.

- 아클란: 리퍼블리카 잇 필리피나스

- 비콜: 필리핀 공화국

- 세부아노: 필리피나스 공화국

- 차바카노: 필리핀 공화국

- 리푸블리카가 필리핀 사람들을 노래한 Hiligaynon

- 아이바나그: 필리핀 공화국

- Ilocano: 필리핀 공화국

- 이바탄: 필리핀 공화국

- 카팜판간: 필리핀 공화국

- 키나라이아: 리푸블리카 강 필리피나스

- Maguindanaon: 필리피나스 공화국

- 마라나오: 필리피나스 공화국

- 판가시난: 필리핀 공화국

- 삼발: 필리핀 공화국

- 수리가온: 필리피나스 공화국

- 타갈로그: 필리핀 공화국

- 타우수그: 필리핀 공화국

- 와라이: 한필리핀스 공화국

- 야칸: 필리핀 공화국

필리핀의 인정된 선택 언어들은 다음과 같습니다.

- 스페인어: 필리핀 공화국

- 아랍어: جمهورية الفلبين어, 로마자: Jumhuriyat al-Filibb ī어

- ^ 이것은 중요한 세부 사항을 생략하고 요약한 것입니다. 자세한 내용은 Schurman Commission § Survey의 필리핀 방문을 참조하십시오.

- ^ 일부 소식통에 따르면 필리핀의 실제 면적은 343,448 km2 (132,606 sq mi)입니다.[197]

참고문헌

- ^ "Flag and Heraldic Code of the Philippines". Metro Manila, Philippines: Official Gazette of the Republic of the Philippines. February 12, 1998. Archived from the original on May 25, 2017. Retrieved March 8, 2014.

- ^ Presidential Decree No. 940, s. 1976 (May 29, 1976), Establishing Manila as the Capital of the Philippines and as the Permanent Seat of the National Government, Manila, Philippines: Official Gazette of the Republic of the Philippines, archived from the original on May 25, 2017, retrieved April 4, 2015

- ^ "Quezon City Local Government – Background". Quezon City Local Government. Archived from the original on August 20, 2020. Retrieved August 25, 2020.

- ^ a b "DepEd adds 7 languages to mother tongue-based education for Kinder to Grade 3". GMA News Online. July 13, 2013. Archived from the original on December 16, 2013. Retrieved February 8, 2023.

- ^ a b c "Article XIV, Section 7". Constitution of the Philippines. Official Gazette of the Republic of the Philippines. 1987. Archived from the original on June 9, 2017. Retrieved February 11, 2023.

- ^ a b Mapa, Claire Dennis S. 2021 Philippines in Figures (PDF) (Booklet). Philippine Statistics Authority. pp. 23–24. ISSN 1655-2539. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 3, 2022. Retrieved July 17, 2022.

- ^ a b "Land Use and Land Classification of the Philippines" (PDF). Infomapper. National Mapping and Resource Information Authority. 1 (2): 10. December 1991. ISSN 0117-1674. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 22, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Boquet, Yves (2017). The Philippine Archipelago. Springer Geography. Cham, Switzerland: Springer. ISBN 978-3-319-51926-5. Retrieved April 25, 2023.

- ^ "Philippines country profile". BBC News. Archived from the original on December 19, 2023. Retrieved January 10, 2024.

- ^ "Philippines". Central Intelligence Agency. February 27, 2023. Archived from the original on January 10, 2021. Retrieved February 24, 2023 – via CIA.gov.

- ^ a b c d e f "Philippines". The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. June 7, 2023. Retrieved June 19, 2023.

- ^ https://psa.gov.ph/

- ^ a b c d e "World Economic Outlook Database, October 2023 Edition. (Philippines)". IMF.org. International Monetary Fund. October 10, 2023. Retrieved October 12, 2023.

- ^ "Highlights of the Preliminary Results of the 2021 Annual Family Income and Expenditure Survey" (Press release). PSA. Archived from the original on May 16, 2023. Retrieved August 15, 2022.

- ^ Human Development Report 2021/22: Uncertain Times, Unsettled Lives: Shaping our Future in a Transforming World (PDF) (Report). New York, N.Y.: United Nations Development Programme. September 8, 2022. Table 1. ISBN 978-92-1-001640-7. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 8, 2022. Retrieved September 8, 2022.

- ^ Philippine Yearbook (1978 ed.). Manila, Philippines: National Economic and Development Authority, National Census and Statistics Office. 1978. p. 716.

- ^ Santos, Bim (July 28, 2021). "Komisyon sa Wikang Filipino reverts to use of 'Pilipinas', does away with 'Filipinas'". The Philippine Star. Archived from the original on July 28, 2021.

- ^ "The 9th to 10th century archaeological evidence of maritime relations between the Philippines and the islands of Southeast Asia". National Museum of the Philippines. n.d. Retrieved December 4, 2023.

- ^ "Pre-colonial Manila". Malacañan Palace: Presidential Museum And Library. Archived from the original on July 24, 2015. Retrieved December 26, 2020.

- ^ a b Scott, William Henry (1994). Barangay: Sixteenth-century Philippine Culture and Society. Quezon City, Philippines: Ateneo de Manila University Press. ISBN 978-971-550-135-4.

- ^ Malcolm, George A. (1916). The Government of the Philippine Islands: Its Development and Fundamentals. Philippine Law Collection. Rochester, N.Y.: Lawyers Co-operative Publishing Company. p. 3. OCLC 578245510.

- ^ Spate, Oskar H.K. (November 2004) [1979]. "Chapter 4. Magellan's Successors: Loaysa to Urdaneta. Two failures: Grijalva and Villalobos". The Spanish Lake. The Pacific since Magellan. Vol. I. London, England: Taylor & Francis. p. 97. doi:10.22459/SL.11.2004. ISBN 978-0-7099-0049-8. Archived from the original on August 5, 2008. Retrieved July 6, 2020.

- ^ Tarling, Nicholas, ed. (1999). The Cambridge History of Southeast Asia. Vol. 2: From c. 1500 to c. 1800. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. p. 12. ISBN 978-0-521-66370-0.

- ^ "The 1899 Malolos Constitution". Official Gazette of the Republic of the Philippines (in Spanish and English). Título I – De la República; Articulo 1. Archived from the original on June 5, 2017. Retrieved February 11, 2023.

- ^ Constantino, Renato (1975). The Philippines: A Past Revisited. Quezon City, Philippines: Tala Pub. Services. ISBN 978-971-8958-00-1.

- ^ "The Jones Law of 1916". Official Gazette of the Republic of the Philippines. August 29, 1916. Section 1.―The Philippines. Archived from the original on August 8, 2017. Retrieved March 12, 2021.

- ^ "The 1935 Constitution". Official Gazette of the Republic of the Philippines. Article XVII, Section 1. Archived from the original on June 25, 2017. Retrieved February 11, 2023.

- ^ "1973 Constitution of the Republic of the Philippines". Official Gazette of the Republic of the Philippines. January 17, 1973. Archived from the original on June 25, 2017. Retrieved March 14, 2021.

- ^ "The Constitution of the Republic of the Philippines". Official Gazette of the Republic of the Philippines. February 11, 1987. Archived from the original on June 7, 2017. Retrieved March 14, 2021.

- ^ Ingicco, T.; van den Bergh, G. D.; Jago-on, C.; Bahain, J.; Chacón, M. G.; Amano, N.; Forestier, H.; King, C.; Manalo, K.; Nomade, S.; Pereira, A.; Reyes, M. C.; Sémah, A.; Shao, Q.; Voinchet, P.; Falguères, C.; Albers, P.C.H.; Lising, M.; Lyras, G.; Yurnaldi, D.; Rochette, P.; Bautista, A.; de Vos, J. (May 1, 2018). "Earliest known hominin activity in the Philippines by 709 thousand years ago". Nature. University of Wollongong. 557 (7704): 233–237. Bibcode:2018Natur.557..233I. doi:10.1038/s41586-018-0072-8. PMID 29720661. S2CID 256771231. Archived from the original on April 29, 2019.

- ^ Greshko, Michael; Wei-Haas, Maya (April 10, 2019). "New species of ancient human discovered in the Philippines". National Geographic. Archived from the original on April 10, 2019. Retrieved October 24, 2020.

- ^ Rincon, Paul (April 10, 2019). "New human species found in Philippines". BBC News. Archived from the original on April 10, 2019. Retrieved October 24, 2020.

- ^ Détroit, Florent; Dizon, Eusebio; Falguères, Christophe; Hameau, Sébastien; Ronquillo, Wilfredo; Sémah, François (2004). "Upper Pleistocene Homo sapiens from the Tabon cave (Palawan, The Philippines): description and dating of new discoveries" (PDF). Human Palaeontology and Prehistory. Elsevier. 3 (2004): 705–712. Bibcode:2004CRPal...3..705D. doi:10.1016/j.crpv.2004.06.004. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 18, 2015.

- ^ Jett, Stephen C. (2017). Ancient Ocean Crossings: Reconsidering the Case for Contacts with the Pre-Columbian Americas. Tuscaloosa, Ala.: University of Alabama Press. pp. 168–171. ISBN 978-0-8173-1939-7.

- ^ Brown, Jessica; Mitchell, Nora J.; Beresford, Michael, eds. (2005). The Protected Landscape Approach: Linking Nature, Culture and Community (PDF). Gland, Switzerland and Cambridge, England: IUCN. pp. 101–102. ISBN 978-2-8317-0797-6. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 8, 2018. Retrieved March 19, 2023.

- ^ Scott, William Henry (1984). Prehispanic Source Materials for the Study of Philippine History. Quezon City, Philippines: New Day Publishers. p. 17. ISBN 978-971-10-0227-5.

- ^ Ness, Immanuel (2014). Bellwood, Peter (ed.). The Global Prehistory of Human Migration. Chichester, West Sussex, England: Wiley-Blackwell. p. 289. ISBN 978-1-118-97059-1.

- ^ Hung, Hsiao-Chun; Iizuka, Yoshiyuki; Bellwood, Peter; Nguyen, Kim Dung; Bellina, Bérénice; Silapanth, Praon; Dizon, Eusebio; Santiago, Rey; Datan, Ipoi; Manton, Jonathan H. (December 11, 2007). "Ancient jades map 3,000 years of prehistoric exchange in Southeast Asia". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. National Academy of Sciences. 104 (50): 19745–19750. doi:10.1073/pnas.0707304104. PMC 2148369. PMID 18048347.

- ^ a b Legarda, Benito Jr. (2001). "Cultural Landmarks and their Interactions with Economic Factors in the Second Millennium in the Philippines". Kinaadman (Wisdom): A Journal of the Southern Philippines. Xavier University – Ateneo de Cagayan. 23: 40.

- ^ Postma, Antoon (1992). "The Laguna Copper-Plate Inscription: Text and Commentary". Philippine Studies. Quezon City, Philippines: Ateneo de Manila University. 40 (2): 182–203. ISSN 0031-7837. Archived from the original on December 8, 2015.

- ^ a b de Graaf, Hermanus Johannes; Kennedy, Joseph; Scott, William Henry (1977). Geschichte: Lieferung 2. Leiden, Switzerland: Brill. p. 198. ISBN 978-90-04-04859-1.

- ^ a b c d e Junker, Laura Lee (1999). Raiding, Trading, and Feasting: The Political Economy of Philippine Chiefdoms. Honolulu, Hawaii: University of Hawaiʻi Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-2035-0.

- ^ Nadeau, Kathleen M. (2002). Liberation Theology in the Philippines: Faith in a Revolution. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 8. ISBN 978-0-275-97198-4.

- ^ Glover, Ian; Bellwood, Peter, eds. (2004). Southeast Asia: From Prehistory to History. London, England: RoutledgeCurzon. p. 267. ISBN 978-0-415-29777-6.

- ^ Ramirez-Faria, Carlos (2007). "Philippines". Concise Encyclopedia of World History. New Delhi, India: Atlantic Publishers & Distributors. p. 560. ISBN 978-8126907755.

- ^ Evangelista, Alfredo E. (1965). "Identifying Some Intrusive Archaeological Materials Found in Philippine Proto-historic Sites" (PDF). Asian Studies: Journal of Critical Perspectives on Asia. Asian Center, University of the Philippines. 3 (1): 87–88. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 29, 2023. Retrieved April 29, 2023.

- ^ a b Ring, Trudy; Salkin, Robert M. & La Boda, Sharon (1996). International Dictionary of Historic Places: Asia and Oceania. Chicago, Ill.: Taylor & Francis. pp. 565–569. ISBN 978-1-884964-04-6.

- ^ Quezon, Manuel L. III; Goitia, Pocholo, eds. (2016). Historical Atlas of the Republic. Manila, Philippines: Presidential Communications Development and Strategic Planning Office. p. 64. ISBN 978-971-95551-6-2.

- ^ a b c Wernstedt, Frederick L.; Spencer, Joseph Earle (January 1967). The Philippine Island World: A Physical, Cultural, and Regional Geography. Berkeley, Calif.: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-03513-3.

- ^ Arcilla, José S. (1998). An Introduction to Philippine History (Fourth enlarged ed.). Quezon City, Philippines: Ateneo de Manila University Press. p. 15. ISBN 978-971-550-261-0.

- ^ Decasa, George C. (1999). The Qur'anic Concept of Umma and Its Function in Philippine Muslim Society. Interreligious and Intercultural Investigations. Vol. 1. Rome, Italy: Pontificia Università Gregoriana. p. 328. ISBN 978-88-7652-812-5.

- ^ a b c d Newson, Linda A. (April 16, 2009). Conquest and Pestilence in the Early Spanish Philippines. Honolulu, Hawaii: University of Hawaiʻi Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-6197-1.

- ^ Carley, Michael; Jenkins, Paul; Smith, Harry, eds. (2013) [2001]. "Chapter 7". Urban Development and Civil Society: The Role of Communities in Sustainable Cities. Sterling, Va.: Routledge. p. 108. ISBN 978-1-134-20050-4.

- ^ Tan, Samuel K. (2008). A History of the Philippines. Quezon City, Philippines: University of the Philippines Press. p. 37. ISBN 978-971-542-568-1.

- ^ Bankoff, Greg (January 1, 2007). "Storms of history: Water, hazard and society in the Philippines: 1565-1930". In Boomgaard, Peter (ed.). A World of Water: Rain, Rivers and Seas in Southeast Asian Histories. Verhandelingen van het Koninklijk Instituut voor Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde. Vol. 240. Leiden, Netherlands: KITLV Press. pp. 153–184. ISBN 978-90-04-25401-5. JSTOR 10.1163/j.ctt1w76vd0.9.

- ^ a b c Woods, Damon L. (2006). The Philippines: A Global Studies Handbook. Santa Barbara, Calif.: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-85109-675-6.

- ^ a b c d e Guillermo, Artemio R. (2012). Historical Dictionary of the Philippines. Historical Dictionaries of Asia, Oceania, and the Middle East (Third ed.). Lanham, Md.: The Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-7246-2.

- ^ Wing, J.T. (2015). Roots of Empire: Forests and State Power in Early Modern Spain, c.1500-1750. Brill's Series in the History of the Environment. Brill. p. 109. ISBN 978-90-04-26137-2.

At the time of Miguel López de Legazpi's voyage in 1564-5, the Philippines were not a unified polity or nation.

- ^ Carson, Arthur L. (1961). Higher Education in the Philippines (PDF). Bulletin. Washington, D.C.: Office of Education, United States Department of Health, Education, and Welfare. p. 7. OCLC 755650. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 13, 2015. Retrieved April 2, 2023.

- ^ a b de Borja, Marciano R. (2005). Basques In The Philippines. The Basque Series. Reno, Nev.: University of Nevada Press. ISBN 978-0-87417-590-5. Archived from the original on March 26, 2022. Retrieved April 25, 2023.

- ^ Seijas, Tatiana (2014). "The Diversity and Reach of the Manila Slave Market". Asian Slaves in Colonial Mexico: From Chinos to Indians. Cambridge Latin American Studies. New York, N.Y.: Cambridge University Press. p. 36. ISBN 978-1-107-06312-9.

- ^ Beaule, Christine; Douglass, John G., eds. (April 21, 2020). The Global Spanish Empire: Five Hundred Years of Place Making and Pluralism. Tucson, Ariz.: University of Arizona Press. p. 204. ISBN 978-0-8165-4084-6.

- ^ Santiago, Fernando A. Jr. (2006). "Isang Maikling Kasaysayan ng Pandacan, Maynila 1589–1898". Malay (in Filipino). De La Salle University. 19 (2): 70–87. ISSN 2243-7851. Retrieved July 18, 2008 – via Philippine E-Journals.

- ^ Andrade, Tonio (2005). "Chapter 4: La Isla Hermosa: The Rise of the Spanish Colony in Northern Taiwan". How Taiwan Became Chinese: Dutch, Spanish and Han colonialization in the Seventeenth Century. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-12855-1. Archived from the original on November 21, 2007 – via Gutenberg-e.

- ^ Giráldez, Arturo (March 19, 2015). The Age of Trade: The Manila Galleons and the Dawn of the Global Economy. Lanham, Md.: Rowman & Littlefield. p. 2. ISBN 978-1-4422-4352-1.

- ^ Acabado, Stephen (March 1, 2017). "The Archaeology of Pericolonialism: Responses of the "Unconquered" to Spanish Conquest and Colonialism in Ifugao, Philippines" (PDF). International Journal of Historical Archaeology. Springer New York. 21 (1): 1–26. doi:10.1007/s10761-016-0342-9. S2CID 254541436. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 6, 2020 – via Springer Link.

- ^ a b c Abinales, Patricio N.; Amoroso, Donna J. (2005). State and Society in the Philippines. Lanham, Md.: Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0-7425-1024-1.

- ^ Constantino, Renato; Constantino, Letizia R. (1975). A History of the Philippines: From the Spanish Colonization to the Second World War. New York, N.Y.: Monthly Review Press. pp. 58–59. ISBN 978-0-85345-394-9.

- ^ Schumacher, John N. (1984). "Syncretism in Philippine Catholicism: Its Historical Causes". Philippine Studies. Quezon City, Philippines: Ateneo de Manila University Press. 32 (3): 254. ISSN 2244-1093. JSTOR 42632710. OCLC 6015358201.

- ^ a b c Halili, Maria Christine N. (2004). Philippine History (First ed.). Manila, Philippines: REX Book Store, Inc. ISBN 978-971-23-3934-9.

- ^ Kane, Herb Kawainui (1996). "The Manila Galleons". In Bob Dye (ed.). Hawaiʻ Chronicles: Island History from the Pages of Honolulu Magazine. Vol. I. Honolulu, Hawaii: University of Hawaiʻi Press. pp. 25–32. ISBN 978-0-8248-1829-6.

- ^ Bolunia, Mary Jane Louise A. "Astilleros: the Spanish shipyards of Sorsogon" (PDF). Proceedings of the 2014 Asia-Pacific Regional Conference on Underwater Cultural Heritage Conference; Session 5: Early Modern Colonialism in the Asia-Pacific Region (Conference proceeding). Honolulu, Hawaii: Asia-Pacific Regional Conference on Underwater Cultural Heritage Planning Committee. p. 1. OCLC 892536655. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 13, 2015. Retrieved October 26, 2015 – via The Museum of Underwater Archaeology.

- ^ McCarthy, William J. (December 1, 1995). "The Yards at Cavite: Shipbuilding in the Early Colonial Philippines". International Journal of Maritime History. SAGE Publications. 7 (2): 149–162. doi:10.1177/084387149500700208. S2CID 163709949.

- ^ a b c d e Ooi, Keat Gin, ed. (2004). Southeast Asia: A Historical Encyclopedia, from Angkor Wat to East Timor. Santa Barbara, Calif.: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-57607-770-2.

- ^ Closmann, Charles Edwin, ed. (2009). War and the Environment: Military Destruction in the Modern Age. College Station, Tex.: Texas A&M University Press. p. 36. ISBN 978-1-60344-380-7.

- ^ Klein, Bernhard; Mackenthun, Gesa, eds. (August 21, 2012). Sea Changes: Historicizing the Ocean. New York, N.Y.: Routledge. pp. 63–66. ISBN 978-1-135-94046-1. Retrieved August 11, 2023.

- ^ a b c d Dolan, Ronald E., ed. (1991). Philippines. Country Studies/Area Handbook Series. Washington, D.C.: GPO for the Library of Congress. Archived from the original on November 9, 2005. Retrieved February 13, 2023 – via Country Studies.

- ^ Crossley, John Newsome (July 28, 2013). Hernando de los Ríos Coronel and the Spanish Philippines in the Golden Age. London, England: Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. pp. 168–169. ISBN 978-1-4094-8242-0.

- ^ Cole, Jeffrey A. (1985). The Potosí Mita, 1573–1700: Compulsory Indian Labor in the Andes. Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press. p. 20. ISBN 978-0-8047-1256-9.

- ^ Hoadley, Stephen; Ruland, Jurgen, eds. (2006). Asian Security Reassessed. Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. p. 215. ISBN 978-981-230-400-1.

- ^ Hefner, Robert W.; Horvatich, Patricia, eds. (September 1, 1997). Islam in an Era of Nation-States: Politics and Religious Renewal in Muslim Southeast Asia. Honolulu, Hawaii: University of Hawaiʻi Press. pp. 43–44. ISBN 978-0-8248-1957-6.

- ^ United States War Department (1903). Annual Report of the Secretary of War (Report). Vol. III. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office. pp. 379–398.

- ^ Warren, James Francis (2007). The Sulu Zone, 1768–1898: The Dynamics of External Trade, Slavery, and Ethnicity in the Transformation of a Southeast Asian Maritime State (Second ed.). Singapore: NUS Press. p. 124. ISBN 978-9971-69-386-2.

- ^ Ramón de Dalmau y de Olivart (1893). Colección de los Tratados, Convenios y Documentos Internacionales Celebrados por Nuestros Gobiernos Con los Estados Extranjeros Desde el Reinado de Doña Isabel II Hasta Nuestros Días, Vol. 4: Acompañados de Notas Historico-Criticas Sobre Su Negociación y Complimiento y Cotejados Con los Textos Originales, Publicada de Real Orden (in Spanish). Madrid, Spain: El Progreso Editorial. pp. 120–123.

- ^ Castro, Amado A. (1982). "Foreign Trade and Economic Welfare in the Last Half-Century of Spanish Rule". Philippine Review of Economics. University of the Philippines School of Economics. 19 (1 & 2): 97–98. ISSN 1655-1516. Archived from the original on February 11, 2023. Retrieved February 11, 2023.

- ^ Romero, Ma. Corona S.; Sta. Romana, Julita R.; Santos, Lourdes Y. (2006). Rizal & the Development of National Consciousness (Second ed.). Quezon City, Philippines: Katha Publishing Co. p. 25. ISBN 978-971-574-103-3.

- ^ Hedman, Eva-Lotta; Sidel, John (2005). Leifer, Michael (ed.). Philippine Politics and Society in the Twentieth Century: Colonial Legacies, Post-Colonial Trajectories. Politics in Asia. London, England: Routledge. p. 71. ISBN 978-1-134-75421-2.

- ^ Steinberg, David Joel (2018). "Chapter 3: A Singular and a Plural Folk". The Philippines: A Singular and a Plural Place. Nations of the Modern World: Asia (Fourth ed.). Boulder, Colo.: Westview Press. The New Filipinos. doi:10.4324/9780429494383. ISBN 978-0-8133-3755-5.

- ^ Schumacher, John N. (1997). The Propaganda Movement, 1880–1895: The Creation of a Filipino Consciousness, the Making of the Revolution (Revised ed.). Manila, Philippines: Ateneo de Manila University Press. pp. 8–9. ISBN 978-971-550-209-2.

- ^ Schumacher, John N. (1998). Revolutionary Clergy: The Filipino Clergy and the Nationalist Movement, 1850–1903. Quezon City, Philippines: Ateneo de Manila University Press. pp. 23–30. ISBN 978-971-550-121-7.

- ^ Acibo, Libert Amorganda; Galicano-Adanza, Estela (1995). Jose P. Rizal: His Life, Works, and Role in the Philippine Revolution. Manila, Philippines: REX Book Store, Inc. pp. 46–47. ISBN 978-971-23-1837-5.

- ^ Owen, Norman G., ed. (January 1, 2005). The Emergence of Modern Southeast Asia: A New History. Honolulu, Hawaii: University of Hawaiʻi Press. p. 156. ISBN 978-0-8248-2841-7.

- ^ Borromeo-Buehler, Soledad (1998). The Cry of Balintawak: A Contrived Controversy: A Textual Analysis with Appended Documents. Quezon City, Philippines: Ateneo de Manila University Press. p. 7. ISBN 978-971-550-278-8.

- ^ a b Duka, Cecilio D. (2008). Struggle for Freedom: A Textbook on Philippine History. Manila, Philippines: REX Book Store, Inc. ISBN 978-971-23-5045-0.

- ^ Abinales, Patricio N. (July 8, 2022). Modern Philippines. Understanding Modern Nations. Santa Barbara, Calif.: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-4408-6005-8.

- ^ Draper, Andrew Sloan (1899). The Rescue of Cuba: An Episode in the Growth of Free Government. New York: Silver Burdett. pp. 170–172. OCLC 9764656.

- ^ Fantina, Robert (2006). Desertion and the American Soldier, 1776–2006. New York: Algora Publishing. p. 83. ISBN 978-0-87586-454-9.

- ^ Starr, J. Barton, ed. (September 1988). The United States Constitution: Its Birth, Growth, and Influence in Asia. Hong Kong, China: Hong Kong University Press. p. 260. ISBN 978-962-209-201-3.

- ^ "The week". The Nation. Vol. 68, no. 1766. May 4, 1899. p. 323.

- ^ Linn, Brian McAllister (2000). The Philippine War, 1899–1902. Lawrence, Kans.: University Press of Kansas. pp. 75–76. ISBN 978-0-7006-1225-3.

- ^ Kalaw, Maximo Manguiat (1927). The Development of Philippine politics (1872-1920). Manila: Oriental Commercial Company, Inc. pp. 199–200.

- ^ Paterno, Pedro Alejandro (June 2, 1899). "Pedro Paterno's Proclamation of War". The Philippine-American War Documents. San Pablo City, Philippines: MSC Institute of Technology, Inc. Retrieved December 25, 2016.

- ^ a b Tucker, Spencer, ed. (May 20, 2009). "Philippine-American War". The Encyclopedia of the Spanish-American and Philippine-American Wars: A Political, Social, and Military History. Vol. I: A–L (Illustrated ed.). Santa Barbara, Calif.: ABC-CLIO. p. 478. ISBN 978-1-85109-951-1.

- ^ Briley, Ron (2020). Talking American History: An Informal Narrative History of the United States. Santa Fe, N.M.: Sunstone Press. p. 247. ISBN 978-1-63293-288-4.

- ^ Cocks, Catherine; Holloran, Peter C.; Lessoff, Alan (March 13, 2009). "Philippine-American War (1899–1902)". Historical Dictionary of the Progressive Era. Historical Dictionaries of U.S. Historical Eras. Vol. 12. Lanham, Md.: The Scarecrow Press. p. 332. ISBN 978-0-8108-6293-7.

- ^ Gates, John M. (November 2002). "Chapter 3: The Pacification of the Philippines". The U.S. Army and Irregular Warfare. OCLC 49327571. Archived from the original on August 5, 2010. Retrieved February 20, 2010 – via College of Wooster.

- ^ Abanes, Menandro Sarion (2014). Ethno-religious Identification and Intergroup Contact Avoidance: An Empirical Study on Christian-Muslim Relations in the Philippines. Nijmegen Studies in Development and Cultural Change. Zürich, Switzerland: LIT Verlag Münster. p. 36. ISBN 978-3-643-90580-2. Retrieved February 11, 2023.

- ^ Federspiel, Howard M. (January 31, 2007). Sultans, Shamans, and Saints: Islam and Muslims in Southeast Asia. Honolulu, Hawaii: University of Hawaiʻi Press. p. 120. ISBN 978-0-8248-3052-6.

- ^ Aguilar-Cariño, Ma. Luisa (1994). "The Igorot as Other: Four Discourses from the Colonial Period". Philippine Studies. Ateneo de Manila University. 42 (2): 194–209. ISSN 0031-7837. JSTOR 42633435.

- ^ Wolff, Stefan; Özkanca, Oya Dursun-, eds. (March 16, 2016). External Interventions in Civil Wars: The Role and Impact of Regional and International Organisations. London, England: Routledge. p. 103. ISBN 978-1-134-91142-4.

- ^ Rogers, Mark M.; Bamat, Tom; Ideh, Julie, eds. (March 24, 2008). Pursuing Just Peace: An Overview and Case Studies for Faith-Based Peacebuilders. Baltimore, Md.: Catholic Relief Services. p. 119. ISBN 978-1-61492-030-4. Archived from the original on February 8, 2009. Retrieved April 25, 2023.

- ^ a b c Armes, Roy (July 29, 1987). Third World Film Making and the West. Berkeley, Calif.: University of California Press. p. 152. ISBN 978-0-520-90801-7.

- ^ a b Tofighian, Nadi (2006). The role of Jose Nepomuceno in the Philippine society: What language did his silent films speak?. DiVA portal (Thesis). Stockholm University. OCLC 1235074310. Archived from the original on March 9, 2012. Retrieved February 9, 2023.

- ^ Nadeau, Kathleen (April 3, 2020). The History of the Philippines. The Greenwood Histories of the Modern Nations (Second ed.). Santa Barbara, Calif.: Greenwood. p. 76. ISBN 978-1-4408-7359-1. Retrieved October 12, 2023.

- ^ Lai To, Lee; Othman, Zarina, eds. (September 1, 2016). Regional Community Building in East Asia: Countries in Focus. Politics in Asia. New York, N.Y.: Routledge. p. 145. ISBN 978-1-317-26556-6.

- ^ a b c Thompson, Roger M. (October 16, 2003). Filipino English and Taglish: Language Switching From Multiple Perspectives. Varieties of English Around the World. Amsterdam, Netherlands: John Benjamins Publishing Company. ISBN 978-90-272-9607-8.

- ^ Gonzales, Cathrine (April 30, 2020). "Celebrating 83 years of women's suffrage in the Philippines". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Archived from the original on May 6, 2020. Retrieved January 29, 2021.

- ^ Kwiatkowski, Lynn (May 20, 2019). Struggling With Development: The Politics of Hunger and Gender in the Philippines. Boulder, Colo.: Westview Press. p. 41. ISBN 978-0-429-96562-3.

- ^ Holden, William N.; Jacobson, R. Daniel (February 15, 2012). Mining and Natural Hazard Vulnerability in the Philippines: Digging to Development or Digging to Disaster?. Anthem Environmental Studies. London, England: Anthem Press. p. 229. ISBN 978-1-84331-396-0.

- ^ Riedinger, Jeffrey M. (1995). Agrarian Reform in the Philippines: Democratic Transitions and Redistributive Reform. Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press. p. 87. ISBN 978-0-8047-2530-9.

- ^ Chamberlain, Sharon W. (March 5, 2019). A Reckoning: Philippine Trials of Japanese War Criminals. New Perspectives in Southeast Asian Studies. Madison, Wis.: University of Wisconsin Press. p. 11. ISBN 978-0-299-31860-4.

- ^ Rankin, Karl L. (November 25, 1943). "Introduction". Document 984 (Report). Foreign Relations of the United States: Diplomatic Papers, 1943, The British Commonwealth, Eastern Europe, the Far East. Vol. III. Office of the Historian. Archived from the original on June 29, 2017. Retrieved February 16, 2021.

- ^ Abinales, Patricio N.; Amoroso, Donna J. (July 6, 2017). State and Society in the Philippines (Second ed.). Lanham, Md.: Rowman & Littlefield. p. 160. ISBN 978-1-5381-0395-1.

- ^ "The Guerrilla War". American Experience. PBS. Archived from the original on January 28, 2017. Retrieved February 24, 2011.

- ^ Minor, Colin (March 4, 2019). "Filipino Guerilla Resistance to Japanese Invasion in World War II". Legacy. 15 (1). Archived from the original on March 20, 2020. Retrieved February 11, 2023 – via Southern Illinois University Carbondale.

- ^ Sandler, Stanley, ed. (2001). "Philippines, Anti-Japanese Guerrillas in". World War II in the Pacific: An Encyclopedia. New York, N.Y.: Garland Publishing. pp. 819–825. ISBN 978-0-8153-1883-5.

- ^ Jones, Jeffrey Frank. Japanese War Crimes and Related Topics: A Guide to Records at the National Archives (PDF). Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration. pp. 1031–1037. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 14, 2010 – via ibiblio.

- ^ Li, Peter (ed.). Japanese War Crimes: The Search for Justice. New Brunswick, N.J.: Transaction Publishers. p. 250. ISBN 978-1-4128-2683-9. Archived from the original on October 2, 2020.

- ^ Rottman, Gordon L. (2002). World War II Pacific Island Guide: A Geo-Military Study. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press. p. 318. ISBN 978-0-313-31395-0.

- ^ Del Gallego, John A. (July 17, 2020). The Liberation of Manila: 28 Days of Carnage, February–March 1945. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland. p. 84. ISBN 978-1-4766-3597-2.

- ^ "Founding Member States". United Nations. Archived from the original on November 21, 2009.

- ^ a b c Bühler, Konrad G. (February 8, 2001). State Succession and Membership in International Organizations: Legal Theories versus Political Pragmatism. Legal Aspects of International Organization. The Hague, Netherlands: Kluwer Law International. ISBN 978-90-411-1553-9.

- ^ Treaties and Other International Agreements of the United States of America; 1776–1949 (PDF). Vol. II. United States: United States Department of State. 1974. pp. 3–6. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 24, 2021.

- ^ Goodwin, Jeff (2001). No Other Way Out: States and Revolutionary Movements, 1945–1991. Cambridge Studies in Comparative Politics. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. p. 118. ISBN 978-0-521-62069-7.

- ^ Tucker, Spencer C., ed. (October 29, 2013). "Hukbalahap Rebellion". Encyclopedia of Insurgency and Counterinsurgency: A New Era of Modern Warfare. Santa Barbara, Calif.: ABC-CLIO. p. 244. ISBN 978-1-61069-280-9.

- ^ "Republic Day". Official Gazette of the Republic of the Philippines. II. Independence Day moved from July 4 to June 12. Archived from the original on February 25, 2018. Retrieved February 12, 2023.

- ^ Dobbs, Charles M. (February 19, 2010). Trade and Security: The United States and East Asia, 1961–1969. Newcastle upon Tyne, England: Cambridge Scholars Publishing. p. 222. ISBN 978-1-4438-1995-4.

- ^ Weatherbee, Donald E.; Emmers, Ralf; Pangestu, Mari; Sebastian, Leonard C. (2005). International Relations in Southeast Asia: The Struggle for Autonomy. Lanham, Md.: Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 68–69. ISBN 978-0-7425-2842-0.

- ^ a b Timberman, David G. (1991). A Changeless Land: Continuity and Change in Philippine Politics. Armonk, N.Y.: M.E. Sharpe. ISBN 978-981-3035-86-7.

- ^ Fernandes, Clinton (June 30, 2008). Hot Spot: Asia and Oceania. Westport, Conn.: ABC-CLIO. p. 188. ISBN 978-0-313-35413-7.

- ^ "Declaration of Martial Law". Official Gazette of the Republic of the Philippines. Archived from the original on July 8, 2017. Retrieved September 1, 2020.

- ^ Hastedt, Glenn P. (January 1, 2004). "Philippines". Encyclopedia of American Foreign Policy. New York, N.Y.: Facts On File. p. 392. ISBN 978-1-4381-0989-3.

- ^ Martin, Gus, ed. (June 15, 2011). "New People's Army". The SAGE Encyclopedia of Terrorism (Second ed.). Thousand Oaks, Calif.: SAGE Publications. p. 427. ISBN 978-1-4522-6638-1.

- ^ van der Kroef, Justus M. (1975). "Asian Communism in the Crucible". Problems of Communism. Documentary Studies Section, International Information Administration. XXIV (March–April 1975): 59.

- ^ The Europa World Year: Kazakhstan – Zimbabwe. Vol. II (45th ed.). London, England: Europa Publications. 2004. p. 3408. ISBN 978-1-85743-255-8.

- ^ Leary, Virginia A.; Ellis, A. A.; Madlener, Kurt (1984). "Chapter 1: An Overview of Human Rights". The Philippines: Human Rights After Martial Law: Report of a Mission (PDF) (Report). Geneva, Switzerland: International Commission of Jurists. ISBN 978-92-9037-023-9. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 29, 2014. Retrieved February 12, 2023.

- ^ van Erven, Eugène (1992). The Playful Revolution: Theatre and Liberation in Asia. Bloomington, Ind.: Indiana University Press. p. 35. ISBN 978-0-253-20729-6.

- ^ Kang, David C. (January 24, 2002). Crony Capitalism: Corruption and Development in South Korea and the Philippines. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. p. 140. ISBN 978-0-521-00408-4.

- ^ White, Lynn T. III (December 17, 2014). Philippine Politics: Possibilities and Problems in a Localist Democracy. Routledge Contemporary Southeast Asia Series. London, England: Routledge. p. 74. ISBN 978-1-317-57422-4.

- ^ Salazar, Lorraine Carlos (2007). Getting a Dial Tone: Telecommunications Liberalisation in Malaysia and the Philippines. Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. pp. 12–13. ISBN 978-981-230-382-0.

- ^ Inoue, M.; Isozaki, H., eds. (November 11, 2013). People and Forest — Policy and Local Reality in Southeast Asia, the Russian Far East, and Japan. Dordrecht, Netherlands: Springer Science & Business Media. p. 142. ISBN 978-94-017-2554-5.

- ^ "UCAN Special Report: What's Behind the Negros Famine Crisis". Union of Catholic Asian News. September 10, 1985. Archived from the original on March 22, 2016. Retrieved February 14, 2023.

- ^ SarDesai, D. R. (December 4, 2012). Southeast Asia: Past and Present (7th ed.). Westview Press. ISBN 978-0-8133-4838-4.

- ^ Vogl, Frank (September 2016). Waging War on Corruption: Inside the Movement Fighting the Abuse of Power. Boulder, Colo.: Rowman & Littlefield. p. 60. ISBN 978-1-4422-1853-6.

- ^ a b c Thompson, Mark R.; Batalla, Eric Vincent C., eds. (February 19, 2018). Routledge Handbook of the Contemporary Philippines. Routledge Handbooks. London, England: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-48526-1.

- ^ Raquiza, Antoinette R. (June 17, 2013). State Structure, Policy Formation, and Economic Development in Southeast Asia: The Political Economy of Thailand and the Philippines. Routledge Studies in the Growth Economies of Asia. London, England: Routledge. pp. 40–41. ISBN 978-1-136-50502-7.

- ^ Quinn-Judge, Paul (September 7, 1983). "Assassination of Aquino linked to power struggle for successor to Marcos". The Christian Science Monitor. Archived from the original on September 8, 2015. Retrieved February 12, 2023.

- ^ Hermida, Ranilo Balaguer (November 19, 2014). Imagining Modern Democracy: A Habermasian Assessment of the Philippine Experiment. Albany, N.Y.: SUNY Press. p. 12. ISBN 978-1-4384-5387-3.

- ^ Atwood, J. Brian; Schuette, Keith E. A Path to Democratic Renewal (PDF) (Report). p. 350. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 12, 2014 – via National Democratic Institute for International Affairs and International Republican Institute.

- ^ a b Fineman, Mark (February 27, 1986). "The 3-Day Revolution: How Marcos Was Toppled". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on August 25, 2020. Retrieved February 12, 2023.

- ^ Burgess, John (April 21, 1986). "Not All Filipinos Glad Marcos Is Out". Washington Post. Archived from the original on February 12, 2023. Retrieved February 12, 2023.

- ^ a b Newhall, Chris; Hendley, James W. II & Stauffer, Peter H. (February 28, 2005). "The Cataclysmic 1991 Eruption of Mount Pinatubo, Philippines (U.S. Geological Survey Fact Sheet 113-97)" (PDF). Reducing the Risk from Volcano Hazards. U.S. Department of the Interior; U.S. Geological Survey. OCLC 731752857. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 17, 2006. Retrieved April 22, 2023.

- ^ Kingsbury, Damien (September 13, 2016). Politics in Contemporary Southeast Asia: Authority, Democracy and Political Change. London, England: Routledge. p. 132. ISBN 978-1-317-49628-1.

- ^ Tan, Andrew T. H., ed. (January 2009). A Handbook of Terrorism and Insurgency in Southeast Asia. Cheltenham, England: Edward Elgar Publishing. p. 405. ISBN 978-1-84720-718-0.

- ^ "The Communist Insurgency in the Philippines: Tactics and Talks" (PDF). Asia Report N°202. International Crisis Group: 5–7. February 14, 2011. OCLC 905388916. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 6, 2020. Retrieved September 2, 2020 – via Refworld.

- ^ Mydans, Seth (September 14, 1986). "Philippine Communists Are Spread Widely, but Not Thinly". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 24, 2015. Retrieved September 2, 2020.

- ^ Pecotich, Anthony; Shultz, Clifford J., eds. (July 22, 2016). Handbook of Markets and Economies: East Asia, Southeast Asia, Australia, New Zealand: East Asia, Southeast Asia, Australia, New Zealand. Armonk, N.Y.: M. E. Sharpe. ISBN 978-1-315-49875-1.

- ^ Ortega, Arnisson Andre (September 9, 2016). Neoliberalizing Spaces in the Philippines: Suburbanization, Transnational Migration, and Dispossession. Lanham, Md.: Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 51–52. ISBN 978-1-4985-3052-1.

- ^ Gargan, Edward A. (December 11, 1997). "Last Laugh for the Philippines; Onetime Joke Economy Avoids Much of Asia's Turmoil". The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 28, 2009. Retrieved January 25, 2008.

- ^ Pempel, T. J., ed. (1999). The Politics of the Asian Economic Crisis. Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press. p. 163. ISBN 978-0-8014-8634-0.

- ^ Rebullida, Ma. Lourdes G. (December 2003). "The Politics of Urban Poor Housing: State and Civil Society Dynamics" (PDF). Philippine Political Science Journal. Philippine Political Science Association. 24 (47): 56. doi:10.1080/01154451.2003.9754247. S2CID 154441392. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 11, 2021. Retrieved February 12, 2023.

- ^ Bhargava, Vinay Kumar; Bolongaita, Emil P. (2004). Challenging Corruption in Asia: Case Studies and a Framework for Action. Directions in Development. Washington, D.C.: World Bank Publications. p. 78. ISBN 978-0-8213-5683-8.

- ^ Landler, Mark (February 9, 2001). "In Philippines, The Economy As Casualty; The President Ousted, a Credibility Repair Job". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 19, 2010. Retrieved February 8, 2023.

- ^ Hutchcroft, Paul D. (Paul David) (2008). "The Arroyo Imbroglio in the Philippines". Journal of Democracy. Johns Hopkins University Press. 19 (1): 141–155. doi:10.1353/jod.2008.0001. ISSN 1086-3214. S2CID 144031968. Retrieved June 16, 2023 – via Project MUSE.

- ^ Dizon, David (August 4, 2010). "Corruption was Gloria's biggest mistake: survey". ABS-CBN News. Archived from the original on August 6, 2010. Retrieved April 15, 2012.

- ^ McCoy, Alfred W. (October 15, 2009). Policing America's Empire: The United States, the Philippines, and the Rise of the Surveillance State. Madison, Wis.: University of Wisconsin Press. p. 498. ISBN 978-0-299-23413-3. Retrieved October 21, 2023.

- ^ a b Lum, Thomas; Dolven, Ben (May 15, 2014). The Republic of the Philippines and U.S. Interests—2014. CRS Reports (Report). Congressional Research Service. OCLC 1121453557. Archived from the original on April 17, 2022. Retrieved September 14, 2020.

- ^ Lucas, Dax (June 8, 2012). "Aquino attributes growth to good governance". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Archived from the original on June 10, 2012. Retrieved September 14, 2020.

- ^ Buendia, Rizal G. (2015). The politics of the Bangsamoro Basic Law. Yuchengco Center, De La Salle University. pp. 3–5. doi:10.13140/RG.2.1.3954.9205/1. OCLC 1243908970. Retrieved May 2, 2023 – via ResearchGate. [ISBN 미지정]

- ^ Clapano, Jose Rodel (February 3, 2016). "Congress buries Bangsamoro bill". The Philippine Star. Archived from the original on September 20, 2018. Retrieved August 24, 2022.

- ^ Alberto-Masakayan, Thea (May 27, 2016). "Duterte, Robredo win 2016 polls". ABS-CBN News. Archived from the original on May 28, 2016. Retrieved May 27, 2016.

- ^ Nicolas, Fiona (November 4, 2016). "Big projects underway in 'golden age' of infrastructure". CNN Philippines. Archived from the original on November 7, 2016. Retrieved September 13, 2020.

- ^ de Vera, Ben O. (August 6, 2020). "Build, Build, Build's 'new normal': 13 projects added, 8 removed". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Archived from the original on August 17, 2020. Retrieved September 13, 2020.

- ^ Baldwin, Clare; Marshall, Andrew R.C. (March 16, 2017). "Between Duterte and a death squad, a Philippine mayor fights drug-war violence". Reuters. Archived from the original on March 16, 2017.

- ^ Merez, Arianne (March 29, 2019). "5,000 killed and 170,000 arrested in war on drugs: police". ABS-CBN News. Archived from the original on March 29, 2019. Retrieved April 16, 2019.

- ^ Caliwan, Christopher Lloyd (March 30, 2022). "Over 24K villages 'drug-cleared' as of February: PDEA". Philippine News Agency. Archived from the original on March 31, 2022.

- ^ Romero, Alexis (December 26, 2017). "Duterte gov't probing over 16,000 drug war-linked deaths as homicide, not EJK". The Philippine Star. Archived from the original on December 26, 2017. Retrieved February 12, 2023.

- ^ Kabiling, Genalyn (March 5, 2021). "Duterte unfazed by drug war criticisms: 'You want me to go prison? So be it'". Manila Bulletin. Archived from the original on March 5, 2021. Retrieved February 12, 2023.

- ^ Maitem, Jeoffrey (January 25, 2019). "It's Official: Majority in So. Philippines Backs Muslim Autonomy Law". BenarNews. Archived from the original on January 26, 2019. Retrieved February 12, 2023.