인생

Life| 인생 | |

|---|---|

| |

| 산호초 위의 다양한 형태의 생명체들 | |

| 과학적 분류 | |

| 도메인 및 수퍼그룹 | |

| 지구에서의 생활: |

생명은 신호전달, 자생과정과 같은 생물학적 과정을 가진 물질과 그렇지 않은 물질을 구분하는 질로 항상성, 조직성, 대사성, 성장, 적응, 자극에 대한 반응, 생식능력에 의해 기술적으로 정의됩니다.자기 조직화 시스템과 같이 많은 철학적 정의들이 제안되어 왔습니다.특히 바이러스는 숙주 세포에서만 복제되기 때문에 정의가 어렵습니다.생명체는 공기, 물, 그리고 토양에서 지구 곳곳에 존재하며, 많은 생태계들이 생물권을 형성합니다.이들 중 일부는 극단적인 애호가들만이 차지하고 있는 가혹한 환경입니다.

생명은 고대부터 연구되어 왔는데, 엠페도클레스의 유물론은 영원한 네 가지 요소로 구성되어 있다고 주장하고, 아리스토텔레스의 유형론은 생명체가 영혼을 가지고 있고 형태와 물질을 모두 구현한다고 주장합니다.생명체는 적어도 35억 년 전에 생겨나 보편적인 공통 조상이 되었습니다.이것은 많은 멸종된 종들을 통해서 현재 존재하는 모든 종들로 진화했고, 일부 종들은 화석으로 흔적을 남겼습니다.생물을 분류하려는 시도 역시 아리스토텔레스로부터 시작되었습니다.현대의 분류는 1740년대 칼 린네의 이항 명명법에서 시작되었습니다.

생물체는 주로 몇 개의 핵심 화학 원소들로 형성된 생화학 분자들로 구성되어 있습니다.모든 생물체는 두 종류의 큰 분자인 단백질과 핵산을 포함하고 있는데, 후자는 보통 DNA와 RNA 둘 다를 포함하고 있습니다: 이것들은 각각의 종류의 단백질을 만드는 지시를 포함하여 각각의 종에 필요한 정보를 전달합니다.그리고, 단백질은 생명체의 많은 화학적 과정을 수행하는 기계의 역할을 합니다.세포는 생명의 구조적이고 기능적인 단위입니다.원핵생물을 포함한 더 작은 생물체들은 작은 단일 세포들로 이루어져 있습니다.주로 진핵생물인 더 큰 유기체들은 단세포로 구성될 수도 있고, 더 복잡한 구조를 가진 다세포일 수도 있습니다.생명체는 지구에서만 확인되지만 외계 생명체는 가능성이 있는 것으로 생각됩니다.인공 생명체는 과학자들과 공학자들에 의해 모의 실험되고 탐구되고 있습니다.

정의들

도전

생명의 정의는 과학자들과 철학자들에게 오랫동안 도전이 되어 왔습니다.[2][3][4]이것은 부분적으로 삶이 물질이 아닌 과정이기 때문입니다.[5][6][7]이것은 지구 밖에서 발달했을지도 모르는 생명체의 특성에 대한 지식이 부족하기 때문에 복잡합니다.[8][9]생명체와 비생명체를 어떻게 구별할 것인가에 대한 철학적 정의도 제시되고 있습니다.[10]생명에 대한 법적 정의는 논의되어 왔지만, 일반적으로 인간 사망을 선언하는 결정과 이 결정의 법적 영향에 초점을 맞추고 있습니다.[11]최소한 123개의 생명의 정의가 정리되었습니다.[12]

기술적

생명에 대한 정의에 대한 합의가 없기 때문에, 생물학에서 대부분의 현재 정의는 설명적입니다.생명은 주어진 환경에서 자신의 존재를 보존, 발전 또는 강화하는 어떤 것의 특징으로 여겨집니다.이는 다음과 같은 특성의 전부 또는 대부분을 의미합니다.[4][13][14][15][16][17]

- 항상성: 일정한 상태를 유지하기 위해 내부 환경을 조절합니다. 예를 들어, 온도를 낮추기 위해 땀을 흘립니다.

- 조직: 구조적으로 하나 이상의 세포로 구성됨 – 생명의 기본 단위

- 신진대사: 에너지의 변환, 화학 물질을 세포 성분으로 변환(아나볼리즘)하고 유기물을 분해하는 데 사용됩니다.생명체는 항상성과 다른 활동을 위해 에너지를 필요로 합니다.

- 성장: 이화작용보다 더 높은 비율의 동화작용을 유지합니다.자라나는 유기체는 크기와 구조가 늘어납니다.

- 적응: 유기체가 서식지에서 더 잘 살 수 있게 되는 진화 과정.[18][19][20]

- 자극에 대한 반응: 외부 화학물질로부터 단세포 생물이 수축하는 것, 다세포 생물의 모든 감각을 포함하는 복잡한 반응, 또는 태양을 향해 도는 식물의 잎의 움직임(광유증), 화학작용.

- 생식: 하나의 부모 유기체로부터 성적으로 또는 두 부모 유기체로부터 성적으로 새로운 개별 유기체를 생산하는 능력.

물리학

물리학적 관점에서, 유기체는 생존이 지시하는 대로 스스로를 재생산하고 진화할 수 있는 조직화된 분자 구조를 가진 열역학적 체계입니다.[21][22]열역학적으로, 생명체는 주변의 그래디언트(gradient)를 이용하여 불완전한 복제물을 만드는 열린 계로 묘사되어 왔습니다.[23]이것을 표현하는 또 다른 방법은 생명체를 "다윈 진화를 겪을 수 있는 자생적인 화학 시스템"으로 정의하는 것입니다. 이 정의는 칼 세이건의 제안에 근거하여 외계 생물학의 목적을 위해 생명체를 정의하려고 시도하는 NASA 위원회에 의해 채택된 것입니다.[24][25]그러나 이에 따르면 성적으로 생식하는 개체는 스스로 진화할 능력이 없어 살아있지 않기 때문에 이 정의는 많은 비판을 받아왔습니다.[26]이 잠재적 결함의 이유는 'NASA의 정의'가 생명을 살아있는 개인이 아닌 현상으로 지칭하기 때문에 불완전하기 때문입니다.[27]하나의 현상으로서의 삶과 하나의 살아있는 개체로서의 삶의 개념에 근거한 대안적인 정의들이 각각 자기유지가능한 정보의 연속체로서, 그리고 이 연속체의 구별되는 요소로서 제시되어 왔습니다.이 접근법의 큰 장점은 생물학적 어휘를 피하면서 수학과 물리학적 측면에서 생명을 정의한다는 것입니다.[27]

생활 시스템

다른 사람들은 분자 화학에 반드시 의존하지 않는 살아있는 시스템 이론 관점을 취합니다.생명에 대한 체계적인 정의 중 하나는 생명체가 스스로 조직화되고 자기 생산적이라는 것입니다.이에 대한 변형으로는 Stuart Kauffman이 스스로를 재현할 수 있는 자율 에이전트 또는 다중 에이전트 시스템으로 정의한 것과 적어도 하나의 열역학적 작업 사이클을 완료하는 것이 있습니다.[28]이 정의는 시간이 지남에 따라 새로운 기능의 진화에 의해 확장됩니다.[29]

죽음.

죽음은 유기체나 세포에서 모든 생명적인 기능이나 과정의 종료입니다.[30][31]죽음을 정의하는 데 있어 어려움 중 하나는 죽음을 삶과 구별하는 것입니다.죽음은 삶이 끝나는 순간이나 삶을 따르는 상태가 시작되는 순간을 가리키는 것 같습니다.[31]그러나 생명 기능의 정지는 종종 장기 시스템에 걸쳐 동시에 발생하지 않기 때문에 언제 사망이 발생했는지를 판단하는 것은 어렵습니다.[32]그러므로 그러한 결심은 삶과 죽음 사이의 개념적 선을 긋는 것을 요구합니다.이것은 생명을 정의하는 방법에 대한 합의가 거의 없기 때문에 문제가 됩니다.죽음의 본질은 수천 년 동안 세계의 종교적 전통과 철학적 탐구의 중심 관심사였습니다.많은 종교들은 영혼을 위한 사후세계나 윤회, 또는 나중에 신체의 부활에 대한 믿음을 유지합니다.[33]

"삶의 끝에서": 바이러스

바이러스가 살아있는 것으로 여겨져야 하는지 아닌지는 논란의 여지가 있습니다.[34][35]그들은 생명체의 형태보다는 단지 유전자 코딩 복제자로 간주되는 경우가 많습니다.[36]그들은 유전자를 가지고 있고, 자연적인 선택에 의해 진화하며,[38][39] 자기 조립을 통해 여러 개의 복제품을 만들어 복제하기 때문에 "생명의 가장자리에 있는 유기체"[37]로 묘사되어 왔습니다.하지만 바이러스는 대사작용을 하지 않고 새로운 제품을 만들기 위해 숙주세포를 필요로 합니다.숙주 세포 내의 바이러스 자가 조립은 생명체가 유기 분자를 자가 조립하는 것으로 시작되었을 수 있다는 가설을 뒷받침할 수 있기 때문에 생명의 기원에 대한 연구에 영향을 미칩니다.[40][41]

공부이력

유물론

생명의 초기 이론들 중 일부는 물질주의적이었고, 존재하는 모든 것은 물질이며, 생명은 단지 물질의 복잡한 형태나 배열일 뿐이라고 주장했습니다.엠페도클레스 (기원전 430년)는 우주의 모든 것이 지구, 물, 공기, 불의 네 가지 영원한 "원소" 또는 "모든 것의 뿌리"의 조합으로 이루어져 있다고 주장했습니다.모든 변화는 이 네 가지 요소의 배열과 재배열에 의해 설명됩니다.다양한 형태의 생명체들은 적절한 요소들의 혼합에 의해 야기됩니다.[42]Democritus (기원전 460년)는 원자론자였습니다; 그는 삶의 본질적인 특징은 영혼을 갖는 것이라고 생각했고, 다른 모든 것들과 마찬가지로 영혼도 불타는 원자들로 구성되어 있다고 생각했습니다.그는 생명과 열 사이의 명백한 연관성과 불이 움직이기 때문에 불에 대해 자세히 설명했습니다.[43]대조적으로 플라톤은 세계는 물질에 불완전하게 반영된 영구적인 형태에 의해 조직되어 있다고 생각했습니다; 형태는 세계에서 관찰되는 규칙성을 설명하면서 방향성이나 지성을 제공했습니다.[44]고대 그리스에서 시작된 기계론적 유물론은 동물과 인간이 함께 기계로서 기능하는 부품의 집합체라고 주장했던 프랑스 철학자 르네 데카르트 (1596–1650)에 의해 부활되고 수정되었습니다.이 아이디어는 그의 책 L'Homme Machine에서 Julien Offray de La Mettrie (1709–1750)에 의해 더욱 발전되었습니다.[45]19세기에 생물학에서 세포이론의 발전은 이 견해를 장려했습니다.찰스 다윈(1859)의 진화론은 자연 선택에 의한 종의 기원에 대한 기계론적 설명입니다.[46]20세기 초에 스테파네 르두크(1853–1939)는 생물학적 과정이 물리학과 화학적 측면에서 이해될 수 있고, 그 성장이 규산나트륨 용액에 담겨진 무기 결정의 성장과 비슷하다는 생각을 장려했습니다.그의 책 La biolie synthétique에[47] 제시된 그의 아이디어는 그의 생전에 널리 기각되었지만, 러셀, 바지 그리고 동료들의 작품에 대한 관심의 부활을 불러 일으켰습니다.[48]

하형론

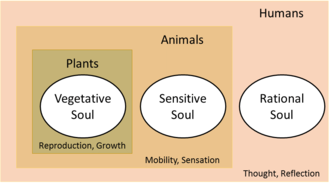

하이로모프론은 그리스 철학자 아리스토텔레스 (기원전 322년)에 의해 처음으로 표현된 이론입니다.생물학에 대한 하이로모피즘의 적용은 아리스토텔레스에게 중요했고 생물학은 그의 현존하는 저술에서 광범위하게 다루어지고 있습니다.이 관점에서 물질세계의 모든 것은 물질과 형식을 모두 가지고 있으며, 생물의 형태는 그 영혼(그리스 정신, 라틴어 애니마)입니다.식물이 자라서 부패하고 자양분을 공급하지만 움직임과 감각을 일으키지 않는 식물의 영혼, 동물이 움직이고 느끼도록 하는 동물의 영혼, 인간에게서만 발견되는 의식과 추론의 근원이 되는 이성적 영혼 등 세 가지 종류의 영혼이 있습니다(아리스톨레는 믿었습니다).[49]각각의 높은 영혼은 낮은 영혼의 모든 속성을 가지고 있습니다.아리스토텔레스는 물질은 형식 없이 존재할 수 있지만, 형식은 물질 없이 존재할 수 없으며, 따라서 영혼은 육체 없이 존재할 수 없다고 믿었습니다.[50]

이 설명은 목적 또는 목표 지향성의 관점에서 현상을 설명하는 삶에 대한 목적론적 설명과 일치합니다.따라서 북극곰의 털이 희다는 것은 위장의 목적으로 설명됩니다.인과관계의 방향(미래에서 과거로)은 자연선택에 대한 과학적 근거와 모순되는 것으로, 그 결과를 선행적 원인의 관점에서 설명합니다.생물학적 특징은 미래의 최적 결과를 보는 것이 아니라, 문제의 특징을 자연스럽게 선택하게 된 종의 과거 진화 역사를 보는 것으로 설명됩니다.[51]

자연발생

자연발생은 살아있는 유기체가 유사한 유기체의 혈통 없이 형성될 수 있다는 믿음이었습니다.일반적으로, 벼룩과 같은 특정한 형태는 먼지와 같은 무생물이나 진흙이나 쓰레기로부터 쥐와 곤충의 계절적 발생으로 추정되는 것으로부터 발생할 수 있다는 생각이었습니다.[52]

자연발생론은 아리스토텔레스에 의해 제안되었는데,[53] 아리스토텔레스는 이전의 자연철학자들의 연구와 유기체의 출현에 대한 다양한 고대 설명들을 집대성하고 확장시켰으며, 그것은 2천년 동안 최고의 설명으로 여겨졌습니다.그것은 1859년 프란체스코 레디와 같은 전임자들의 조사로 확장된 루이스 파스퇴르의 실험에 의해 결정적으로 불식되었습니다.[54][55]자연발생의 전통적인 개념에 대한 반증은 더 이상 생물학자들 사이에서 논란이 되지 않습니다.[56][57][58]

활력소

생명주의는 비물질적인 생명 원칙이 존재한다는 믿음입니다.이것은 Georg Ernst Stahl (17세기)에 의해 시작되었고, 19세기 중반까지 인기가 있었습니다.그것은 앙리 베르그송, 프리드리히 니체, 빌헬름 딜테와 같은 철학자들,[59] 자비에 비차트와 같은 해부학자들, 그리고 쥐스투스 폰 리빅과 같은 화학자들의 관심을 끌었습니다.[60]생명론에는 유기물질과 무기물질은 근본적인 차이가 있다는 생각과 유기물질은 생물로부터만 얻을 수 있다는 믿음이 포함되어 있었습니다.이것은 1828년 프리드리히 뵐러(Friedrich Wöhler)가 무기 재료로 요소를 준비하면서 증명되었습니다.[61]이 뵐러 합성은 현대 유기화학의 출발점으로 여겨집니다.무기반응에서 처음으로 유기화합물이 생성되었기 때문에 역사적으로 의미가 있습니다.[60]

1850년대에 율리우스 로베르트 폰 메이어가 예상한 헤르만 폰 헬름홀츠는 근육 운동에서 에너지가 손실되지 않는다는 것을 보여주었고, 이는 근육을 움직이는 데 필요한 "생명력"이 없다는 것을 암시했습니다.[62]이러한 결과는 특히 효모의 세포가 없는 추출물에서 알코올 발효가 일어날 수 있다는 에두아르트 부흐너의 증명 이후 생명력 이론에 대한 과학적 관심을 포기하게 만들었습니다.[63]그럼에도 불구하고, 믿음은 질병과 질병을 가상의 활력이나 생명력의 교란으로 인한 것으로 해석하는 동종병증과 같은 의사과학 이론에 여전히 존재합니다.[64]

발전

−4500 — – — – −4000 — – — – −3500 — – — – −3000 — – — – −2500 — – — – −2000 — – — – −1500 — – — – −1000 — – — – −500 — – — – 0 — |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

생명의 기원

지구의 나이는 약 45억 4천만년입니다.[65]지구상의 생명체는 적어도 35억 년 동안 존재해 왔으며,[66][67][68][69] 가장 오래된 생명체의 물리적 흔적은 37억 년 전으로 거슬러 올라갑니다.[70][71]타임트리 공개 데이터베이스에 요약된 분자 시계의 추정치는 약 40억년 전 생명의 기원을 나타냅니다.[72]생명의 기원에 대한 가설들은 단순한 유기 분자로부터 세포 이전의 생명을 거쳐 원형 세포와 대사에 이르는 보편적인 공통 조상의 형성을 설명하려고 시도합니다.[73]2016년, 마지막 보편적 공통 조상의 유전자 355개 세트가 잠정적으로 확인되었습니다.[74]

생물권은 적어도 약 35억년 전에 생명의 기원 이후부터 발달한 것으로 추정됩니다.[75]지구상에서 생명체가 살 수 있는 가장 초기의 증거는 서부 그린란드의[70] 37억 년 된 퇴적암에서 발견된 생체원성 흑연과 서부 오스트레일리아의 34억 8천만 년 된 사암에서 발견된 미생물 매트 화석입니다.[71]보다 최근인 2015년, 웨스턴 오스트레일리아(Western Australia)의 41억 년 된 암석에서 "생물학적 생명체의 잔해"가 발견되었습니다.[66]2017년, 캐나다 퀘벡 누부아지투크 벨트의 열수구 침전물에서 화석화된 미생물(또는 미생물체)로 추정되는 것이 발견되었다고 발표되었는데, 이는 지구상 생명체의 가장 오래된 기록으로 44억 년 후에 "거의 순간적인 생명체의 출현"을 시사합니다. 45억 4천만 년 전 지구가 형성된 지 얼마 되지 않아요.[76]

진화

진화는 생물학적 집단의 유전적 특성이 연속적인 세대에 걸쳐 변화하는 것입니다.그것은 새로운 종의 출현과 종종 오래된 종들이 사라지는 결과를 낳습니다.[77][78]진화는 자연 선택(성적 선택 포함)과 유전적 이동과 같은 진화 과정이 유전적 변이에 영향을 미쳐 특정 특성이 연속 세대에 걸쳐 인구 내에서 빈도가 증가하거나 감소할 때 발생합니다.[79]진화의 과정은 생물학적 조직의 모든 단계에서 생물학적 다양성을 낳았습니다.[80][81]

화석

화석은 먼 과거의 동물, 식물, 그리고 다른 유기체들의 흔적 혹은 보존된 잔해입니다.화석 기록은 발견된 화석과 발견되지 않은 화석의 총체와 퇴적암의 층(지층)에 위치하는 것으로 알려져 있습니다.보존된 표본은 임의의 날짜인 1만 년 전보다 더 오래된 것이라면 화석이라고 불립니다.[82]따라서 화석의 나이는 홀로세 시대가 시작될 무렵의 가장 어린 것부터 고대인 에온의 가장 오래된 것까지 다양하며, 나이는 최대 34억년입니다.[83][84]

소멸

멸종은 한 종이 멸종하는 과정입니다.[85]멸종의 순간은 그 종의 마지막 개체의 죽음입니다.종의 잠재적 범위가 매우 클 수 있기 때문에, 이 순간을 결정하는 것은 어렵고, 대개 명백한 부재 기간 후에 소급하여 수행됩니다.종들은 변화하는 서식지나 우월한 경쟁에 맞서 더 이상 살아남을 수 없게 되면 멸종됩니다.지금까지 살아왔던 모든 종의 99% 이상이 현재 멸종되었습니다.[86][87][88][89]대멸종은 새로운 집단의 유기체들이 다양화될 수 있는 기회를 제공함으로써 진화를 가속화 시켰을 수 있습니다.[90]

환경조건

지구 생명체의 다양성은 유전적 기회, 대사 능력, 환경 문제, [91]공생 사이의 역동적인 상호작용의 결과입니다.[92][93][94]지구의 거주 가능 환경은 대부분 미생물에 의해 지배되어 왔고, 그들의 신진대사와 진화의 과정을 거쳤습니다.이러한 미생물 활동의 결과로, 지구의 물리적-화학적 환경은 지질학적 시간 척도로 변화하고 있으며, 이로 인해 후속 생명체의 진화 경로에 영향을 미치고 있습니다.[91]예를 들어, 광합성의 부산물로서 시아노박테리아에 의한 분자 산소의 방출은 지구의 환경에 세계적인 변화를 유도했습니다.그 당시 산소는 지구상의 대부분의 생명체들에게 독성이 있었기 때문에, 이것은 새로운 진화론적인 도전을 제기했고, 결국 지구의 주요 동물과 식물 종의 형성이라는 결과를 낳았습니다.생물체와 환경 사이의 이러한 상호작용은 생물계의 고유한 특징입니다.[91]

생물권

생물권은 모든 생태계의 세계적인 총합입니다.그것은 또한 지구상의 생명체의 영역, (태양과 우주의 복사와 지구 내부의 열을 제외한) 닫힌 시스템, 그리고 대부분 자기 조절의 영역으로 명명될 수 있습니다.[96]생물체는 토양, 온천, 지하 최소 19km (12mi) 깊이의 바위, 바다의 가장 깊은 부분, 그리고 대기 중 최소 64km (40m) 높이의 바위 안을 포함하여 생물권의 모든 부분에 존재합니다.[97][98][99]예를 들어, Aspergillus niger의 포자는 48에서 77 km 고도의 중층권에서 발견되었습니다.[100]실험 조건에서 생명체는 우주의 거의[101][102] 무중력 상태에서 번성하고 우주의 진공 상태에서 살아남는 것으로 관찰되었습니다.[103][104]깊은 마리아나 해구와 [105]미국 북서부 연안의 2,590 m (8,500 ft; 1.61 mi)[106][107] 바다 밑 해저 580 m (1,900 ft; 0.36 mi), 일본 앞바다 해저 2,400 m (7,900 ft; 1.5 mi)의 바위 안에서 생명체들이 번성합니다.[108]2014년, 남극대륙의 얼음 아래 800미터 (2,600피트; 0.50마일)에서 생명체들이 살고 있는 것이 발견되었습니다.[109][110]국제 해양 발견 프로그램의 탐험대는 난카이 트로프 해저 1.2km 아래의 120°C 퇴적물에서 단세포 생명체를 발견했습니다.[111]한 연구자에 따르면, "어디에서나 미생물을 찾을 수 있습니다. 미생물은 조건에 매우 적응력이 뛰어나고 어디에 있든 생존할 수 있습니다."[106]

허용오차범위

생태계의 비활성 구성 요소는 생명체에 필요한 물리적, 화학적 요소입니다. 에너지(태양광 또는 화학적 에너지), 물, 열, 대기, 중력, 영양, 자외선 태양 방사선 보호 등입니다.[112]대부분의 생태계에서, 조건은 낮 동안 그리고 계절마다 다릅니다.그렇다면, 대부분의 생태계에서 살기 위해서는 유기체는 "관용의 범위"라고 불리는 다양한 조건에서 살아남을 수 있어야 합니다.[113]그 밖에는 생존과 번식은 가능하지만 최적이 아닌 "생리적 스트레스의 영역"이 있습니다.이 지역 너머에는 그 유기체의 생존과 번식이 불가능하거나 불가능한 "불관용 지역"이 있습니다.허용 오차 범위가 넓은 생물은 허용 오차 범위가 좁은 생물보다 더 넓게 분포합니다.[113]

익스트림 애호가

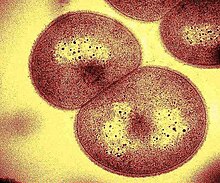

일부 미생물들은 생존하기 위해 냉동, 완전 건조, 기아, 높은 수준의 방사선 노출, 그리고 다른 물리적 또는 화학적 도전들을 견디도록 진화해왔습니다.이러한 극세사 미생물은 그러한 조건에 장기간 노출되어 생존할 수 있습니다.[91][114]그들은 흔하지 않은 에너지 자원을 이용하는 데 뛰어납니다.이러한 극한 환경에서 미생물 군집의 구조 및 대사적 다양성에 대한 특성화는 진행 중입니다.[115]

분류

고대

유기체의 첫 번째 분류는 그리스 철학자 아리스토텔레스 (기원전 384–322)에 의해 만들어졌는데, 그들은 주로 움직이는 능력에 따라 생물을 식물이나 동물로 분류했습니다.그는 피가 있는 동물과 피가 없는 동물을 각각 척추동물과 무척추동물의 개념과 비교할 수 있는 구분하고, 피가 있는 동물을 생체성 사지동물(포유류), 난생성 사지동물( 파충류와 양서류), 조류, 어류, 고래 등 다섯 그룹으로 나눴습니다.그 무혈 동물들은 다섯 개의 그룹으로 나뉘었습니다: 두족류, 갑각류, 곤충 (거미, 전갈, 지네를 포함), 껍질을 벗긴 동물 (대부분의 연체동물과 극피동물), 그리고 "동물원" (식물을 닮은 동물).이것은 그가 죽은 후에도 수 세기 동안 최고의 권위로 남아있었습니다.[116]

린내안

1740년대 후반, 칼 린네는 종의 분류를 위해 이항 명명법을 도입했습니다.린네는 불필요한 수사학을 폐지하고 새로운 서술어를 도입하고 그 의미를 정확하게 정의함으로써 구성을 개선하고 이전에 사용된 여러 단어의 이름의 길이를 줄이고자 했습니다.[117]

그 곰팡이는 원래 식물로 취급되었습니다.짧은 기간 동안 린네는 그것들을 애니멀리아의 베르메스에 분류했지만 나중에 플랜태에 다시 배치했습니다.허버트 코플랜드(Herbert Copeland)는 그의 프로토옥티스타(Protectista)에서 균류를 단세포 유기체와 함께 분류하여 부분적으로 문제를 피했지만 특별한 지위를 인정했습니다.[118]휘태커가 그의 다섯 왕국 체제에서 그들에게 그들만의 왕국을 주었을 때, 그 문제는 결국 해결되었습니다.진화 역사는 그 곰팡이가 식물보다는 동물과 더 밀접한 관련이 있다는 것을 보여줍니다.[119]

현미경의 발전으로 세포와 미생물에 대한 상세한 연구가 가능해지면서 새로운 생명체 집단이 밝혀졌고, 세포생물학과 미생물학 분야가 생겨났습니다.이 새로운 유기체들은 원래 원생동물에서 동물로 그리고 원생동물에서 식물로 원생동물/탈로피타로 구분되어 기술되었지만, 프로티스타 왕국에서 에른스트 해켈에 의해 통합되었습니다; 나중에 원생생물들은 모네라 왕국에서 분리되었고, 결국 박테리아와 고균이라는 두 개의 별개의 그룹으로 나뉘게 되었습니다.이것은 6국 체제로 이어졌고, 결국 진화적 관계에 기반을 둔 현재의 3국 체제로 이어졌습니다.[120]그러나 진핵생물의 분류, 특히 원생생물의 분류는 여전히 논란의 여지가 있습니다.[121]

미생물학이 발달하면서 세포가 아닌 바이러스가 발견됐습니다.이것들이 살아있는 것으로 여겨지는지 여부는 논쟁의 여지가 있습니다; 바이러스는 세포막, 대사, 그리고 그들의 환경에 성장하거나 반응하는 능력과 같은 생명체의 특성이 부족합니다.바이러스는 유전자에 따라 "종"으로 분류되어 왔지만, 그러한 분류의 많은 측면은 여전히 논란의 여지가 있습니다.[122]

원래의 린내 시스템은 다음과 같이 여러 번 수정되었습니다.

| 린네 1735[123] | 해켈 1866[124] | 채튼 1925[125] | 코플랜드 1938[126] | 휘태커 1969[127] | Woese. 1990[120] | 캐벌리어 스미스 1998,[128] 2015[129] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2왕국 | 삼국지 | 제국2개 | 4왕국 | 오왕국 | 도메인 3개 | 제국 2개, 6/7왕국 |

| (처리되지 않음) | 프로티스타 | 원핵생물 | 모네라 | 모네라 | 박테리아 | 박테리아 |

| 고세아 | 고아라 (2015) | |||||

| 진핵생물 | 프로톡티스타 | 프로티스타 | 유카리아 | 원생동물 | ||

| 크로미스타 | ||||||

| 채소류 | 플랜태 | 플랜태 | 플랜태 | 플랜태 | ||

| 곰팡이 | 곰팡이 | |||||

| 애니멀리아 | 애니멀리아 | 애니멀리아 | 애니멀리아 | 애니멀리아 |

진핵생물을 소수의 왕국으로 조직화하려는 시도는 도전을 받아왔습니다.원생동물은 분류군이나 자연적인 그룹을 형성하지 않으며,[130] 크로미스타(Chromalveolata)도 형성하지 않습니다.[131]

구성.

화학 원소

모든 생명체는 생화학적 기능을 위해 특정한 핵심 화학 원소를 필요로 합니다.여기에는 탄소, 수소, 질소, 산소, 인, 황 등 모든 생물체의 주요 영양소가 포함됩니다.[132]이것들은 함께 살아있는 물질의 대부분인 핵산, 단백질, 지질을 구성합니다.이들 6개 원소 중 5개 원소는 DNA의 화학 성분을 포함하고 있으며, 유황은 예외입니다.후자는 아미노산인 시스테인과 메티오닌의 성분입니다.생물체에서 이러한 원소들 중 가장 풍부한 것은 탄소인데, 탄소는 다수의 안정적인 공유 결합을 형성하는 바람직한 특성을 가지고 있습니다.이것은 탄소 기반의 (유기) 분자가 유기 화학에 묘사된 엄청나게 다양한 화학적 배열을 형성할 수 있게 해줍니다.[133]이러한 요소들 중 하나 이상을 제거하거나, 목록에 없는 요소로 원소를 교체하거나, 필요한 카이랄성 또는 다른 화학적 특성을 변경하는 가상의 생화학 유형이 대안으로 제안되었습니다.[134][135]

디엔에이

디옥시리보핵산 또는 DNA는 모든 알려진 생물체와 많은 바이러스의 성장, 발달, 기능, 번식에 사용되는 대부분의 유전적 지시를 전달하는 분자입니다.DNA와 RNA는 핵산입니다; 단백질과 복합 탄수화물과 함께, 그것들은 알려진 모든 형태의 생명체에 필수적인 3가지 종류의 거대 분자들 중 하나입니다.대부분의 DNA 분자는 이중나선을 형성하기 위해 서로 감기는 두 개의 생체고분자 가닥으로 이루어져 있습니다.두 DNA 가닥은 뉴클레오티드라고 불리는 단순한 단위로 구성되어 있기 때문에 폴리뉴클레오티드라고 알려져 있습니다.[136]각각의 뉴클레오타이드는 디옥시리보스라고 불리는 당과 인산기뿐만 아니라 시토신(C), 구아닌(G), 아데닌(A), 티민(T)과 같은 질소를 함유한 핵염기로 구성되어 있습니다.뉴클레오티드는 한 뉴클레오티드의 당과 다음 뉴클레오티드의 인산 사이의 공유 결합에 의해 연쇄적으로 서로 결합되어 교대로 당-인산 골격을 형성합니다.염기쌍 규칙(A는 T, C는 G)에 따르면, 수소 결합은 두 개의 분리된 폴리뉴클레오티드 가닥의 질소성 염기를 결합시켜 이중 가닥 DNA를 만듭니다.이것은 각 가닥이 다른 가닥을 다시 만드는 데 필요한 모든 정보를 포함한다는 핵심적인 특성을 가지고 있어 재생 및 세포 분할 중에 정보를 보존할 수 있습니다.[137]세포 안에서 DNA는 염색체라고 불리는 긴 구조로 조직됩니다.세포 분열 동안 이 염색체들은 DNA 복제 과정에서 복제되어 각 세포에 자신만의 완전한 염색체 집합을 제공합니다.진핵생물은 대부분의 DNA를 세포핵 안에 저장합니다.[138]

셀

세포는 모든 생물체의 구조의 기본 단위이며, 모든 세포는 분열에 의해 기존의 세포로부터 생겨납니다.[139][140]세포 이론은 앙리 뒤트로셰, 테오도르 슈반, 루돌프 비르초 등에 의해 19세기 초에 만들어졌고, 그 후 널리 받아들여졌습니다.[141]유기체의 활동은 세포들의 전체 활동에 달려있는데, 그 세포들 안에서 그리고 그들 사이에서 에너지 흐름이 일어납니다.세포는 세포 분열 동안 유전자 코드로 전달되는 유전 정보를 포함합니다.[142]

세포의 진화적 기원을 반영하는 두 가지 주요 유형이 있습니다.원핵 세포는 원형 DNA와 리보솜을 가지고 있지만, 핵과 다른 막 결합 소기관이 없습니다.박테리아와 고균은 원핵생물의 두 영역입니다.다른 주요 유형은 미토콘드리아, 엽록체, 리소좀, 거칠고 부드러운 소포체, 그리고 진공을 포함한 핵막과 막 결합된 소기관에 의해 결합된 뚜렷한 핵을 가진 진핵세포입니다.게다가, 그들의 DNA는 염색체로 조직됩니다.동물, 식물, 곰팡이를 포함한 모든 종의 거대한 복합 생물은 진핵생물이지만, 원생 미생물의 다양성을 가지고 있습니다.[143]전통적인 모델은 진핵생물이 원핵생물로부터 진화했다는 것이고, 진핵생물의 주요 소기관은 박테리아와 전구 진핵세포 사이의 내생성을 통해 형성된다는 것입니다.[144]

세포 생물학의 분자적 메커니즘은 단백질에 기반을 두고 있습니다.이들 대부분은 단백질 생합성이라고 불리는 효소 촉매 과정을 통해 리보솜에 의해 합성됩니다.아미노산의 배열은 세포의 핵산의 유전자 발현에 기초하여 조립되고 결합됩니다.[145]진핵세포에서, 이 단백질들은 목적지로의 파견을 준비하기 위해 골지체를 통해 운반되고 가공될 수 있습니다.[146]

세포는 부모 세포가 두 개 이상의 딸 세포로 분열하는 세포 분열 과정을 통해 번식합니다.원핵생물의 경우, DNA가 복제되는 핵분열 과정을 통해 세포 분열이 일어나고, 그 후 두 개의 복사본이 세포막의 일부에 부착됩니다.진핵생물에서는 더 복잡한 유사분열 과정이 뒤따릅니다.그러나 결과는 동일합니다. 결과적인 세포 복사본은 서로 동일하고 원래 세포와 동일하며(변이를 제외하고), 둘 다 단계 간 주기 후에 더 많은 분할이 가능합니다.[147]

다세포구조

다세포 생물은 처음에 동일한 세포들의 집단 형성을 통해 진화했을 수 있습니다.이 세포들은 세포 부착을 통해 집단 유기체를 형성할 수 있습니다.집단의 개별 구성원들은 스스로 생존할 수 있는 반면, 진정한 다세포 유기체의 구성원들은 생존을 위해 유기체의 나머지에 의존하게 만드는 전문화를 발전시켰습니다.그러한 유기체들은 성체 유기체를 형성하는 다양한 특수화된 세포를 형성할 수 있는 하나의 생식 세포로부터 또는 클론으로 형성됩니다.이 전문화는 다세포 생물이 단세포보다 더 효율적으로 자원을 이용할 수 있게 해줍니다.[148]약 8억년 전에, GK-PID라는 효소라는 하나의 분자의 작은 유전적인 변화는 유기체가 하나의 세포 유기체에서 많은 세포들 중 하나로 가도록 했을지도 모릅니다.[149]

세포들은 그들의 미세한 환경을 인지하고 반응하는 방법들을 진화시켜왔고, 그로 인해 그들의 적응력을 향상시켰습니다.세포 신호 전달은 세포 활동을 조정하기 때문에 다세포 생물의 기본적인 기능을 지배합니다.세포간 신호전달은 주스타크린 신호전달을 이용한 직접적인 세포접촉을 통해 발생할 수도 있고, 내분비계에서처럼 간접적으로 작용제의 교환을 통해 발생할 수도 있습니다.좀 더 복잡한 유기체에서는, 활동의 조정이 전용 신경계를 통해 일어날 수 있습니다.[150]

외계인

비록 생명체는 지구에서만 확인되지만, 많은 사람들은 외계 생명체가 그럴듯할 뿐만 아니라 가능성이 있거나 불가피하다고 생각합니다.[151][152]태양계의 다른 행성들과 달들과 다른 행성계들은 한때 단순한 생명체들을 지지했던 증거를 찾기 위해 조사되고 있으며, SETI와 같은 프로젝트들은 가능한 외계 문명들로부터의 전파를 탐지하기 위해 노력하고 있습니다.태양계 내에서 미생물의 생명체를 수용할 수 있는 다른 장소로는 화성의 지하, 금성의 대기 상층,[153] 그리고 거대한 행성들의 위성들 중 일부의 지하 바다가 있습니다.[154][155]

지구 생명체의 끈기와 다재다능함에 대한 조사와 [114]일부 유기체가 그러한 극단에서 살아남기 위해 사용하는 분자 시스템에 대한 이해는 외계 생명체의 탐색에 중요합니다.[91]예를 들어, 이끼는 모의 화성 환경에서 한 달 동안 생존할 수 있습니다.[156][157]

태양계를 넘어, 지구와 같은 행성에서 지구와 같은 생명체를 지탱할 수 있는 또 다른 주계열성 주변 지역은 거주 가능 지역으로 알려져 있습니다.이 영역의 내부와 외부 반지름은 항성의 광도에 따라 변하며, 이 영역이 생존하는 시간 간격도 변합니다.태양보다 질량이 큰 별들은 생명체가 살 수 있는 영역이 더 크지만, 태양과 같은 항성진화의 "주계열"에 더 짧은 시간 동안 머물러 있습니다.작은 적색 왜성은 반대의 문제를 가지고 있는데, 더 작은 거주가능 영역은 더 높은 수준의 자기 활동과 가까운 궤도로부터의 조석 잠금의 영향을 받습니다.따라서, 태양과 같은 중간 질량 범위에 있는 별들은 지구와 같은 생명체가 발달할 가능성이 더 높습니다.[158]은하 내에서 별의 위치는 생명체가 형성될 가능성에도 영향을 미칠 수 있습니다.행성을 형성할 수 있는 더 무거운 원소가 풍부한 지역에 있는 별들은 서식지를 파괴할 수 있는 초신성 사건의 비율이 낮으며, 복잡한 생명체를 가진 행성이 존재할 확률이 더 높을 것으로 예측됩니다.[159]드레이크 방정식의 변수는 불확실성의 범위 내에서 문명이 존재할 가능성이 가장 높은 행성계의 조건을 논의하는 데 사용됩니다.[160]지구 밖 생명체의 증거를 보고하기 위한 "생명체 탐지의 확신" 척도(CoLD)가 제안되었습니다.[161][162]

인조

인공 생명체는 컴퓨터, 로봇공학, 생화학과 같은 삶의 어떤 측면의 시뮬레이션입니다.[163]합성생물학은 과학과 생물공학을 융합한 생명공학의 새로운 분야입니다.공동의 목표는 자연에서 발견되지 않는 새로운 생물학적 기능과 시스템의 설계와 구축입니다.합성 생물학은 정보를 처리하고, 화학 물질을 조작하고, 물질과 구조를 제작하고, 에너지를 생산하고, 음식을 제공하고, 인간의 건강과 환경을 유지하고 향상시키는 공학적인 생물학적 시스템을 설계하고 구축할 수 있는 궁극적인 목표를 가진 생명공학의 광범위한 재정의와 확장을 포함합니다.[164]

참고 항목

- 생물학, 생명에 대한 연구.

- 바이오시그니처

- 인생사

- 개체수에 따른 생물 목록

- 실행가능계이론

- 분자생물학의 중심 교조

- 탄소기반생활

메모들

참고문헌

- ^ International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses Executive Committee (May 2020). "The New Scope of Virus Taxonomy: Partitioning the Virosphere Into 15 Hierarchical Ranks". Nature Microbiology. 5 (5): 668–674. doi:10.1038/s41564-020-0709-x. PMC 7186216. PMID 32341570.

- ^ Tsokolov, Serhiy A. (May 2009). "Why Is the Definition of Life So Elusive? Epistemological Considerations". Astrobiology. 9 (4): 401–412. Bibcode:2009AsBio...9..401T. doi:10.1089/ast.2007.0201. PMID 19519215.

- ^ Emmeche, Claus (1997). "Defining Life, Explaining Emergence". Niels Bohr Institute. Archived from the original on 14 March 2012. Retrieved 25 May 2012.

- ^ a b McKay, Chris P. (14 September 2004). "What Is Life—and How Do We Search for It in Other Worlds?". PLOS Biology. 2 (9): 302. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0020302. PMC 516796. PMID 15367939.

- ^ Mautner, Michael N. (1997). "Directed panspermia. 3. Strategies and motivation for seeding star-forming clouds" (PDF). Journal of the British Interplanetary Society. 50: 93–102. Bibcode:1997JBIS...50...93M. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 November 2012.

- ^ Mautner, Michael N. (2000). Seeding the Universe with Life: Securing Our Cosmological Future (PDF). Washington D.C. ISBN 978-0-476-00330-9. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 November 2012.

{{cite book}}: CS1 유지 관리: 위치 누락 게시자(링크) - ^ McKay, Chris (18 September 2014). "What is life? It's a Tricky, Often Confusing Question". Astrobiology Magazine.

- ^ Nealson, K.H.; Conrad, P.G. (December 1999). "Life: past, present and future". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London B. 354 (1392): 1923–1939. doi:10.1098/rstb.1999.0532. PMC 1692713. PMID 10670014. Archived from the original on 3 January 2016.

- ^ Mautner, Michael N. (2009). "Life-centered ethics, and the human future in space" (PDF). Bioethics. 23 (8): 433–440. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8519.2008.00688.x. PMID 19077128. S2CID 25203457. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 November 2012.

- ^ Jeuken M (1975). "The biological and philosophical defitions of life". Acta Biotheoretica. 24 (1–2): 14–21. doi:10.1007/BF01556737. PMID 811024. S2CID 44573374.

- ^ Capron AM (1978). "Legal definition of death". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 315 (1): 349–362. Bibcode:1978NYASA.315..349C. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1978.tb50352.x. PMID 284746. S2CID 36535062.

- ^ Trifonov, Edward N. (17 March 2011). "Vocabulary of Definitions of Life Suggests a Definition". Journal of Biomolecular Structure and Dynamics. 29 (2): 259–266. doi:10.1080/073911011010524992. PMID 21875147.

- ^ Koshland, Daniel E. Jr. (22 March 2002). "The Seven Pillars of Life". Science. 295 (5563): 2215–2216. doi:10.1126/science.1068489. PMID 11910092.

- ^ "life". The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (4th ed.). Houghton Mifflin. 2006. ISBN 978-0-618-70173-5.

- ^ "Life". Merriam-Webster Dictionary. Archived from the original on 13 December 2021. Retrieved 25 July 2022.

- ^ "Habitability and Biology: What are the Properties of Life?". Phoenix Mars Mission. The University of Arizona. Archived from the original on 16 April 2014. Retrieved 6 June 2013.

- ^ Trifonov, Edward N. (2012). "Definition of Life: Navigation through Uncertainties" (PDF). Journal of Biomolecular Structure & Dynamics. 29 (4): 647–650. doi:10.1080/073911012010525017. ISSN 0739-1102. PMID 22208269. S2CID 8616562. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 January 2012. Retrieved 12 January 2012.

- ^ Dobzhansky, Theodosius (1968). "On Some Fundamental Concepts of Darwinian Biology". Evolutionary Biology. Boston, MA: Springer US. pp. 1–34. doi:10.1007/978-1-4684-8094-8_1. ISBN 978-1-4684-8096-2. Archived from the original on 30 July 2022. Retrieved 23 July 2022.

- ^ Wang, Guanyu (2014). Analysis of complex diseases : a mathematical perspective. Boca Raton. ISBN 978-1-4665-7223-2. OCLC 868928102. Archived from the original on 30 July 2022. Retrieved 23 July 2022.

{{cite book}}: CS1 유지 관리: 위치 누락 게시자(링크) - ^ Sejian, Veerasamy; Gaughan, John; Baumgard, Lance; Prasad, C. S., eds. (2015). Climate change impact on livestock : adaptation and mitigation. New Delhi. ISBN 978-81-322-2265-1. OCLC 906025831. Archived from the original on 30 July 2022. Retrieved 23 July 2022.

{{cite book}}: CS1 유지 관리: 위치 누락 게시자(링크) - ^ Luttermoser, Donald G. "ASTR-1020: Astronomy II Course Lecture Notes Section XII" (PDF). East Tennessee State University. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 March 2012. Retrieved 28 August 2011.

- ^ Luttermoser, Donald G. (Spring 2008). "Physics 2028: Great Ideas in Science: The Exobiology Module" (PDF). East Tennessee State University. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 March 2012. Retrieved 28 August 2011.

- ^ Lammer, H.; Bredehöft, J.H.; Coustenis, A.; Khodachenko, M.L.; et al. (2009). "What makes a planet habitable?" (PDF). The Astronomy and Astrophysics Review. 17 (2): 181–249. Bibcode:2009A&ARv..17..181L. doi:10.1007/s00159-009-0019-z. S2CID 123220355. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 June 2016. Retrieved 3 May 2016.

Life as we know it has been described as a (thermodynamically) open system (Prigogine et al. 1972), which makes use of gradients in its surroundings to create imperfect copies of itself.

- ^ Benner, Steven A. (December 2010). "Defining Life". Astrobiology. 10 (10): 1021–1030. Bibcode:2010AsBio..10.1021B. doi:10.1089/ast.2010.0524. ISSN 1531-1074. PMC 3005285. PMID 21162682.

- ^ Joyce, Gerald F. (1995). "The RNA World: Life before DNA and Protein". Extraterrestrials. Cambridge University Press. pp. 139–151. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511564970.017. hdl:2060/19980211165. ISBN 978-0-511-56497-0. S2CID 83282463. Archived from the original on 27 May 2013. Retrieved 27 May 2012.

- ^ Benner, Steven A. (December 2010). "Defining Life". Astrobiology. 10 (10): 1021–1030. Bibcode:2010AsBio..10.1021B. doi:10.1089/ast.2010.0524. ISSN 1531-1074. PMC 3005285. PMID 21162682.

- ^ a b Piast, Radosław W. (June 2019). "Shannon's information, Bernal's biopoiesis and Bernoulli distribution as pillars for building a definition of life". Journal of Theoretical Biology. 470: 101–107. Bibcode:2019JThBi.470..101P. doi:10.1016/j.jtbi.2019.03.009. PMID 30876803. S2CID 80625250. Archived from the original on 15 December 2019. Retrieved 1 January 2023.

- ^ Kaufmann, Stuart (2004). "Autonomous agents". In Barrow, John D.; Davies, P.C.W.; Harper, Jr., C.L. (eds.). Science and Ultimate Reality. pp. 654–666. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511814990.032. ISBN 978-0-521-83113-0.

- ^ Longo, Giuseppe; Montévil, Maël; Kauffman, Stuart (1 January 2012). "No entailing laws, but enablement in the evolution of the biosphere". Proceedings of the 14th annual conference companion on Genetic and evolutionary computation. GECCO '12. pp. 1379–1392. arXiv:1201.2069. Bibcode:2012arXiv1201.2069L. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.701.3838. doi:10.1145/2330784.2330946. ISBN 978-1-4503-1178-6. S2CID 15609415. Archived from the original on 11 May 2017.

- ^ Definition of death. Archived from the original on 3 November 2009.

- ^ a b "Definition of death". Encyclopedia of Death and Dying. Advameg, Inc. Archived from the original on 3 February 2007. Retrieved 25 May 2012.

- ^ Henig, Robin Marantz (April 2016). "Crossing Over: How Science Is Redefining Life and Death". National Geographic. Archived from the original on 1 November 2017. Retrieved 23 October 2017.

- ^ "How the Major Religions View the Afterlife". Encyclopedia.com. Archived from the original on 4 February 2022. Retrieved 4 February 2022.

- ^ "Virus". Genome.gov. Archived from the original on 11 May 2022. Retrieved 25 July 2022.

- ^ "Are Viruses Alive?". Yellowstone Thermal Viruses. Archived from the original on 14 June 2022. Retrieved 25 July 2022.

- ^ Koonin, E.V.; Starokadomskyy, P. (7 March 2016). "Are viruses alive? The replicator paradigm sheds decisive light on an old but misguided question". Studies in the History and Philosophy of Biology and Biomedical Science. 59: 125–134. doi:10.1016/j.shpsc.2016.02.016. PMC 5406846. PMID 26965225.

- ^ Rybicki, EP (1990). "The classification of organisms at the edge of life, or problems with virus systematics". S Afr J Sci. 86: 182–186.

- ^ Holmes, E.C. (October 2007). "Viral evolution in the genomic age". PLOS Biol. 5 (10): e278. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0050278. PMC 1994994. PMID 17914905.

- ^ Forterre, Patrick (3 March 2010). "Defining Life: The Virus Viewpoint". Orig Life Evol Biosph. 40 (2): 151–160. Bibcode:2010OLEB...40..151F. doi:10.1007/s11084-010-9194-1. PMC 2837877. PMID 20198436.

- ^ Koonin, E.V.; Senkevich, T.G.; Dolja, V.V. (2006). "The ancient Virus World and evolution of cells". Biology Direct. 1: 29. doi:10.1186/1745-6150-1-29. PMC 1594570. PMID 16984643.

- ^ Rybicki, Ed (November 1997). "Origins of Viruses". Archived from the original on 9 May 2009. Retrieved 12 April 2009.

- ^ Parry, Richard (4 March 2005). "Empedocles". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Archived from the original on 13 May 2012. Retrieved 25 May 2012.

- ^ Parry, Richard (25 August 2010). "Democritus". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Archived from the original on 30 August 2006. Retrieved 25 May 2012.

- ^ Hankinson, R.J. (1997). Cause and Explanation in Ancient Greek Thought. Oxford University Press. p. 125. ISBN 978-0-19-924656-4.

- ^ de la Mettrie, J.J.O. (1748). L'Homme Machine [Man a machine]. Leyden: Elie Luzac.

- ^ Thagard, Paul (2012). The Cognitive Science of Science: Explanation, Discovery, and Conceptual Change. MIT Press. pp. 204–205. ISBN 978-0-262-01728-2.

- ^ Leduc, Stéphane (1912). La Biologie Synthétique [Synthetic Biology]. Paris: Poinat.

- ^ Russell, Michael J.; Barge, Laura M.; Bhartia, Rohit; et al. (2014). "The Drive to Life on Wet and Icy Worlds". Astrobiology. 14 (4): 308–343. Bibcode:2014AsBio..14..308R. doi:10.1089/ast.2013.1110. PMC 3995032. PMID 24697642.

- ^ Aristotle. On the Soul. Book II.

- ^ Marietta, Don (1998). Introduction to ancient philosophy. M.E. Sharpe. p. 104. ISBN 978-0-7656-0216-9. Retrieved 25 August 2020.

- ^ Stewart-Williams, Steve (2010). Darwin, God and the meaning of life: how evolutionary theory undermines everything you thought you knew of life. Cambridge University Press. pp. 193–194. ISBN 978-0-521-76278-6.

- ^ Stillingfleet, Edward (1697). Origines Sacrae. Cambridge University Press.

- ^ André Brack (1998). "Introduction" (PDF). In André Brack (ed.). The Molecular Origins of Life. Cambridge University Press. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-521-56475-5. Retrieved 7 January 2009.

- ^ Levine, Russell; Evers, Chris. "The Slow Death of Spontaneous Generation (1668–1859)". North Carolina State University. National Health Museum. Archived from the original on 9 October 2015. Retrieved 6 February 2016.

- ^ Tyndall, John (1905). Fragments of Science. Vol. 2. New York: P.F. Collier. Chapters IV, XII, and XIII.

- ^ Bernal, J.D. (1967) [Reprinted work by A.I. Oparin originally published 1924; Moscow: The Moscow Worker]. The Origin of Life. The Weidenfeld and Nicolson Natural History. Translation of Oparin by Ann Synge. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. LCCN 67098482.

- ^ Zubay, Geoffrey (2000). Origins of Life: On Earth and in the Cosmos (2nd ed.). Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-12-781910-5.

- ^ Smith, John Maynard; Szathmary, Eors (1997). The Major Transitions in Evolution. Oxford Oxfordshire: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-850294-4.

- ^ Schwartz, Sanford (2009). C.S. Lewis on the Final Frontier: Science and the Supernatural in the Space Trilogy. Oxford University Press. p. 56. ISBN 978-0-19-988839-9.

- ^ a b Wilkinson, Ian (1998). "History of Clinical Chemistry – Wöhler & the Birth of Clinical Chemistry" (PDF). The Journal of the International Federation of Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine. 13 (4). Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 January 2016. Retrieved 27 December 2015.

- ^ Friedrich Wöhler (1828). "Ueber künstliche Bildung des Harnstoffs". Annalen der Physik und Chemie. 88 (2): 253–256. Bibcode:1828AnP....88..253W. doi:10.1002/andp.18280880206. Archived from the original on 10 January 2012.

- ^ Rabinbach, Anson (1992). The Human Motor: Energy, Fatigue, and the Origins of Modernity. University of California Press. pp. 124–125. ISBN 978-0-520-07827-7.

- ^ Cornish-Bowden Athel, ed. (1997). New Beer in an Old Bottle. Eduard Buchner and the Growth of Biochemical Knowledge. Valencia, Spain: Universitat de València. ISBN 978-8437-033280.

- ^ "NCAHF Position Paper on Homeopathy". National Council Against Health Fraud. February 1994. Archived from the original on 25 December 2018. Retrieved 12 June 2012.

- ^ Dalrymple, G. Brent (2001). "The age of the Earth in the twentieth century: a problem (mostly) solved". Special Publications, Geological Society of London. 190 (1): 205–221. Bibcode:2001GSLSP.190..205D. doi:10.1144/GSL.SP.2001.190.01.14. S2CID 130092094.

- ^ a b Bell, Elizabeth A.; Boehnike, Patrick; Harrison, T. Mark; et al. (19 October 2015). "Potentially biogenic carbon preserved in a 4.1 billion-year-old zircon" (PDF). PNAS. 112 (47): 14518–14521. Bibcode:2015PNAS..11214518B. doi:10.1073/pnas.1517557112. ISSN 1091-6490. PMC 4664351. PMID 26483481. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 November 2015. Retrieved 20 October 2015.

- ^ Schopf, J.W. (June 2006). "Fossil evidence of Archaean life". Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 361 (1470): 869–885. doi:10.1098/rstb.2006.1834. PMC 1578735. PMID 16754604.

- ^ Hamilton Raven, Peter; Brooks Johnson, George (2002). Biology. McGraw-Hill Education. p. 68. ISBN 978-0-07-112261-0. Retrieved 7 July 2013.

- ^ Milsom, Clare; Rigby, Sue (2009). Fossils at a Glance (2nd ed.). John Wiley & Sons. p. 134. ISBN 978-1-4051-9336-8.

- ^ a b Ohtomo, Yoko; Kakegawa, Takeshi; Ishida, Akizumi; Nagase, Toshiro; Rosing, Minik T. (8 December 2013). "Evidence for biogenic graphite in early Archaean Isua metasedimentary rocks". Nature Geoscience. 7 (1): 25–28. Bibcode:2014NatGe...7...25O. doi:10.1038/ngeo2025.

- ^ a b Noffke, Nora; Christian, Daniel; Wacey, David; Hazen, Robert M. (8 November 2013). "Microbially Induced Sedimentary Structures Recording an Ancient Ecosystem in the ca. 3.48 Billion-Year-Old Dresser Formation, Pilbara, Western Australia". Astrobiology. 13 (12): 1103–1124. Bibcode:2013AsBio..13.1103N. doi:10.1089/ast.2013.1030. PMC 3870916. PMID 24205812.

- ^ Hedges, S. B. Hedges (2009). "Life". In S. B. Hedges; S. Kumar (eds.). The Timetree of Life. Oxford University Press. pp. 89–98. ISBN 978-0-1995-3503-3.

- ^ "Habitability and Biology: What are the Properties of Life?". Phoenix Mars Mission. The University of Arizona. Archived from the original on 17 April 2014. Retrieved 6 June 2013.

- ^ Wade, Nicholas (25 July 2016). "Meet Luca, the Ancestor of All Living Things". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 28 July 2016. Retrieved 25 July 2016.

- ^ Campbell, Neil A.; Brad Williamson; Robin J. Heyden (2006). Biology: Exploring Life. Boston, Massachusetts: Pearson Prentice Hall. ISBN 978-0-13-250882-7. Archived from the original on 2 November 2014. Retrieved 15 June 2016.

- ^ Dodd, Matthew S.; Papineau, Dominic; Grenne, Tor; et al. (1 March 2017). "Evidence for early life in Earth's oldest hydrothermal vent precipitates". Nature. 543 (7643): 60–64. Bibcode:2017Natur.543...60D. doi:10.1038/nature21377. PMID 28252057. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017. Retrieved 2 March 2017.

- ^ Hall, Brian K.; Hallgrímsson, Benedikt (2008). Strickberger's Evolution (4th ed.). Sudbury, Massachusetts: Jones and Bartlett Publishers. pp. 4–6. ISBN 978-0-7637-0066-9. LCCN 2007008981. OCLC 85814089.

- ^ "Evolution Resources". Washington, DC: National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. 2016. Archived from the original on 3 June 2016.

- ^ Scott-Phillips, Thomas C.; Laland, Kevin N.; Shuker, David M.; et al. (May 2014). "The Niche Construction Perspective: A Critical Appraisal". Evolution. 68 (5): 1231–1243. doi:10.1111/evo.12332. ISSN 0014-3820. PMC 4261998. PMID 24325256.

Evolutionary processes are generally thought of as processes by which these changes occur. Four such processes are widely recognized: natural selection (in the broad sense, to include sexual selection), genetic drift, mutation, and migration (Fisher 1930; Haldane 1932). The latter two generate variation; the first two sort it.

- ^ Hall & Hallgrimsson 2008, pp.

- ^ Voet, Donald; Voet, Judith G.; Pratt, Charlotte W. (2016). Fundamentals of Biochemistry: Life at the Molecular Level (Fifth ed.). Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons. Chapter 1: Introduction to the Chemistry of Life, pp. 1–22. ISBN 978-1-118-91840-1. LCCN 2016002847. OCLC 939245154.

- ^ "Frequently Asked Questions". San Diego Natural History Museum. Archived from the original on 10 May 2012. Retrieved 25 May 2012.

- ^ Vastag, Brian (21 August 2011). "Oldest 'microfossils' raise hopes for life on Mars". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 19 October 2011. Retrieved 21 August 2011.

- ^ Wade, Nicholas (21 August 2011). "Geological Team Lays Claim to Oldest Known Fossils". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 1 May 2013. Retrieved 21 August 2011.

- ^ Extinction – definition. Archived from the original on 26 September 2009.

- ^ "What is an extinction?". Late Triassic. Bristol University. Archived from the original on 1 September 2012. Retrieved 27 June 2012.

- ^ McKinney, Michael L. (1996). "How do rare species avoid extinction? A paleontological view". In Kunin, W.E.; Gaston, Kevin (eds.). The Biology of Rarity: Causes and consequences of rare—common differences. Springer. ISBN 978-0-412-63380-5. Retrieved 26 May 2015.

- ^ Stearns, Beverly Peterson; Stearns, Stephen C. (2000). Watching, from the Edge of Extinction. Yale University Press. p. x. ISBN 978-0-300-08469-6. Retrieved 30 May 2017.

- ^ Novacek, Michael J. (8 November 2014). "Prehistory's Brilliant Future". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 29 December 2014. Retrieved 25 December 2014.

- ^ Van Valkenburgh, B. (1999). "Major patterns in the history of carnivorous mammals". Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences. 27: 463–493. Bibcode:1999AREPS..27..463V. doi:10.1146/annurev.earth.27.1.463. Archived from the original on 29 February 2020. Retrieved 29 June 2019.

- ^ a b c d e Rothschild, Lynn (September 2003). "Understand the evolutionary mechanisms and environmental limits of life". NASA. Archived from the original on 29 March 2012. Retrieved 13 July 2009.

- ^ King, G.A.M. (April 1977). "Symbiosis and the origin of life". Origins of Life and Evolution of Biospheres. 8 (1): 39–53. Bibcode:1977OrLi....8...39K. doi:10.1007/BF00930938. PMID 896191. S2CID 23615028.

- ^ Margulis, Lynn (2001). The Symbiotic Planet: A New Look at Evolution. London: Orion Books. ISBN 978-0-7538-0785-9.

- ^ Futuyma, D.J.; Janis Antonovics (1992). Oxford surveys in evolutionary biology: Symbiosis in evolution. Vol. 8. London, England: Oxford University Press. pp. 347–374. ISBN 978-0-19-507623-3.

- ^ Liedert, Christina; Peltola, Minna; Bernhardt, Jörg; Neubauer, Peter; Salkinoja-Salonen, Mirja (15 March 2012). "Physiology of Resistant Deinococcus geothermalis Bacterium Aerobically Cultivated in Low-Manganese Medium". Journal of Bacteriology. 194 (6): 1552–1561. doi:10.1128/JB.06429-11. ISSN 0021-9193. PMC 3294853. PMID 22228732.

- ^ "Biosphere". The Columbia Encyclopedia (6th ed.). Columbia University Press. 2004. Archived from the original on 27 October 2011.

- ^ University of Georgia (25 August 1998). "First-Ever Scientific Estimate Of Total Bacteria On Earth Shows Far Greater Numbers Than Ever Known Before". Science Daily. Archived from the original on 10 November 2014. Retrieved 10 November 2014.

- ^ Hadhazy, Adam (12 January 2015). "Life Might Thrive a Dozen Miles Beneath Earth's Surface". Astrobiology Magazine. Archived from the original on 12 March 2017. Retrieved 11 March 2017.

- ^ Fox-Skelly, Jasmin (24 November 2015). "The Strange Beasts That Live in Solid Rock Deep Underground". BBC online. Archived from the original on 25 November 2016. Retrieved 11 March 2017.

- ^ Imshenetsky, AA; Lysenko, SV; Kazakov, GA (June 1978). "Upper boundary of the biosphere". Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 35 (1): 1–5. Bibcode:1978ApEnM..35....1I. doi:10.1128/aem.35.1.1-5.1978. ISSN 0099-2240. PMC 242768. PMID 623455.

- ^ Dvorsky, George (13 September 2017). "Alarming Study Indicates Why Certain Bacteria Are More Resistant to Drugs in Space". Gizmodo. Archived from the original on 14 September 2017. Retrieved 14 September 2017.

- ^ Caspermeyer, Joe (23 September 2007). "Space flight shown to alter ability of bacteria to cause disease". Arizona State University. Archived from the original on 14 September 2017. Retrieved 14 September 2017.

- ^ Dose, K.; Bieger-Dose, A.; Dillmann, R.; et al. (1995). "ERA-experiment "space biochemistry"". Advances in Space Research. 16 (8): 119–129. Bibcode:1995AdSpR..16h.119D. doi:10.1016/0273-1177(95)00280-R. PMID 11542696.

- ^ Horneck G.; Eschweiler, U.; Reitz, G.; Wehner, J.; Willimek, R.; Strauch, K. (1995). "Biological responses to space: results of the experiment "Exobiological Unit" of ERA on EURECA I". Adv. Space Res. 16 (8): 105–118. Bibcode:1995AdSpR..16h.105H. doi:10.1016/0273-1177(95)00279-N. PMID 11542695.

- ^ Glud, Ronnie; Wenzhöfer, Frank; Middelboe, Mathias; et al. (17 March 2013). "High rates of microbial carbon turnover in sediments in the deepest oceanic trench on Earth". Nature Geoscience. 6 (4): 284–288. Bibcode:2013NatGe...6..284G. doi:10.1038/ngeo1773.

- ^ a b Choi, Charles Q. (17 March 2013). "Microbes Thrive in Deepest Spot on Earth". LiveScience. Archived from the original on 2 April 2013. Retrieved 17 March 2013.

- ^ Oskin, Becky (14 March 2013). "Intraterrestrials: Life Thrives in Ocean Floor". LiveScience. Archived from the original on 2 April 2013. Retrieved 17 March 2013.

- ^ Morelle, Rebecca (15 December 2014). "Microbes discovered by deepest marine drill analysed". BBC News. Archived from the original on 16 December 2014. Retrieved 15 December 2014.

- ^ Fox, Douglas (20 August 2014). "Lakes under the ice: Antarctica's secret garden". Nature. 512 (7514): 244–246. Bibcode:2014Natur.512..244F. doi:10.1038/512244a. PMID 25143097.

- ^ Mack, Eric (20 August 2014). "Life Confirmed Under Antarctic Ice; Is Space Next?". Forbes. Archived from the original on 22 August 2014. Retrieved 21 August 2014.

- ^ Heuer, Verena B.; Inagaki, Fumio; Morono, Yuki; et al. (4 December 2020). "Temperature limits to deep subseafloor life in the Nankai Trough subduction zone". Science. 370 (6521): 1230–1234. Bibcode:2020Sci...370.1230H. doi:10.1126/science.abd7934. hdl:2164/15700. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 33273103. S2CID 227257205. Archived from the original on 31 March 2021. Retrieved 8 March 2021.

- ^ "Essential requirements for life". CMEX-NASA. Archived from the original on 17 August 2009. Retrieved 14 July 2009.

- ^ a b Chiras, Daniel C. (2001). Environmental Science – Creating a Sustainable Future (6th ed.). Sudbury, MA : Jones and Bartlett. ISBN 978-0-7637-1316-4.

- ^ a b Chang, Kenneth (12 September 2016). "Visions of Life on Mars in Earth's Depths". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 12 September 2016. Retrieved 12 September 2016.

- ^ Rampelotto, Pabulo Henrique (2010). "Resistance of microorganisms to extreme environmental conditions and its contribution to astrobiology". Sustainability. 2 (6): 1602–1623. Bibcode:2010Sust....2.1602R. doi:10.3390/su2061602.

- ^ "Aristotle". University of California Museum of Paleontology. Archived from the original on 20 November 2016. Retrieved 15 November 2016.

- ^ Knapp, Sandra; Lamas, Gerardo; Lughadha, Eimear Nic; Novarino, Gianfranco (April 2004). "Stability or stasis in the names of organisms: the evolving codes of nomenclature". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London B. 359 (1444): 611–622. doi:10.1098/rstb.2003.1445. PMC 1693349. PMID 15253348.

- ^ Copeland, Herbert F. (1938). "The Kingdoms of Organisms". Quarterly Review of Biology. 13 (4): 383. doi:10.1086/394568. S2CID 84634277.

- ^ Whittaker, R.H. (January 1969). "New concepts of kingdoms or organisms. Evolutionary relations are better represented by new classifications than by the traditional two kingdoms". Science. 163 (3863): 150–160. Bibcode:1969Sci...163..150W. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.403.5430. doi:10.1126/science.163.3863.150. PMID 5762760.

- ^ a b Woese, C.; Kandler, O.; Wheelis, M. (1990). "Towards a natural system of organisms:proposal for the domains Archaea, Bacteria, and Eucarya". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 87 (12): 4576–9. Bibcode:1990PNAS...87.4576W. doi:10.1073/pnas.87.12.4576. PMC 54159. PMID 2112744.

- ^ Adl, S.M.; Simpson, A.G.; Farmer, M.A.; et al. (2005). "The new higher level classification of eukaryotes with emphasis on the taxonomy of protists". Journal of Eukaryotic Microbiology. 52 (5): 399–451. doi:10.1111/j.1550-7408.2005.00053.x. PMID 16248873. S2CID 8060916.

- ^ Van Regenmortel MH (January 2007). "Virus species and virus identification: past and current controversies". Infection, Genetics and Evolution. 7 (1): 133–144. doi:10.1016/j.meegid.2006.04.002. PMID 16713373. S2CID 86179057.

- ^ Linnaeus, C. (1735). Systemae Naturae, sive regna tria naturae, systematics proposita per classes, ordines, genera & species.

- ^ Haeckel, E. (1866). Generelle Morphologie der Organismen. Reimer, Berlin.

- ^ Chatton, É. (1925). "Pansporella perplexa. Réflexions sur la biologie et la phylogénie des protozoaires". Annales des Sciences Naturelles - Zoologie et Biologie Animale. 10-VII: 1–84.

- ^ Copeland, H. (1938). "The kingdoms of organisms". Quarterly Review of Biology. 13 (4): 383–420. doi:10.1086/394568. S2CID 84634277.

- ^ Whittaker, R. H. (January 1969). "New concepts of kingdoms of organisms". Science. 163 (3863): 150–60. Bibcode:1969Sci...163..150W. doi:10.1126/science.163.3863.150. PMID 5762760.

- ^ Cavalier-Smith, T. (1998). "A revised six-kingdom system of life". Biological Reviews. 73 (3): 203–66. doi:10.1111/j.1469-185X.1998.tb00030.x. PMID 9809012. S2CID 6557779.

- ^ Ruggiero, Michael A.; Gordon, Dennis P.; Orrell, Thomas M.; Bailly, Nicolas; Bourgoin, Thierry; Brusca, Richard C.; Cavalier-Smith, Thomas; Guiry, Michael D.; Kirk, Paul M.; Thuesen, Erik V. (2015). "A higher level classification of all living organisms". PLOS ONE. 10 (4): e0119248. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1019248R. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0119248. PMC 4418965. PMID 25923521.

- ^ Simpson, Alastair G.B.; Roger, Andrew J. (2004). "The real 'kingdoms' of eukaryotes". Current Biology. 14 (17): R693–R696. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2004.08.038. PMID 15341755. S2CID 207051421.

- ^ Harper, J.T.; Waanders, E.; Keeling, P.J. (2005). "On the monophyly of chromalveolates using a six-protein phylogeny of eukaryotes". International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology. 55 (Pt 1): 487–496. doi:10.1099/ijs.0.63216-0. PMID 15653923.

- ^ Hotz, Robert Lee (3 December 2010). "New link in chain of life". The Wall Street Journal. Dow Jones & Company. Archived from the original on 17 August 2017.

Until now, however, they were all thought to share the same biochemistry, based on the Big Six, to build proteins, fats and DNA.

- ^ Lipkus, Alan H.; Yuan, Qiong; Lucas, Karen A.; et al. (28 May 2008). "Structural Diversity of Organic Chemistry. A Scaffold Analysis of the CAS Registry". The Journal of Organic Chemistry. American Chemical Society (ACS). 73 (12): 4443–4451. doi:10.1021/jo8001276. ISSN 0022-3263. PMID 18505297.

- ^ Committee on the Limits of Organic Life in Planetary Systems; Committee on the Origins and Evolution of Life; National Research Council (2007). The Limits of Organic Life in Planetary Systems. National Academy of Sciences. ISBN 978-0-309-66906-1. Archived from the original on 10 May 2012. Retrieved 3 June 2012.

- ^ Benner, Steven A.; Ricardo, Alonso; Carrigan, Matthew A. (December 2004). "Is there a common chemical model for life in the universe?" (PDF). Current Opinion in Chemical Biology. 8 (6): 672–689. doi:10.1016/j.cbpa.2004.10.003. PMID 15556414. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 October 2012. Retrieved 3 June 2012.

- ^ Purcell, Adam (5 February 2016). "DNA". Basic Biology. Archived from the original on 5 January 2017. Retrieved 15 November 2016.

- ^ Nuwer, Rachel (18 July 2015). "Counting All the DNA on Earth". The New York Times. New York. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 18 July 2015. Retrieved 18 July 2015.

- ^ Russell, Peter (2001). iGenetics. New York: Benjamin Cummings. ISBN 978-0-8053-4553-7.

- ^ "2.2: The Basic Structural and Functional Unit of Life: The Cell". LibreTexts. 2 June 2019. Archived from the original on 29 March 2020. Retrieved 29 March 2020.

- ^ Bose, Debopriya (14 May 2019). "Six Main Cell Functions". Leaf Group Ltd./Leaf Group Media. Archived from the original on 29 March 2020. Retrieved 29 March 2020.

- ^ Sapp, Jan (2003). Genesis: The Evolution of Biology. Oxford University Press. pp. 75–78. ISBN 978-0-19-515619-5.

- ^ Lintilhac, P.M. (January 1999). "Thinking of biology: toward a theory of cellularity—speculations on the nature of the living cell" (PDF). BioScience. 49 (1): 59–68. doi:10.2307/1313494. JSTOR 1313494. PMID 11543344. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 April 2013. Retrieved 2 June 2012.

- ^ Whitman, W.; Coleman, D.; Wiebe, W. (1998). "Prokaryotes: The unseen majority". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 95 (12): 6578–6583. Bibcode:1998PNAS...95.6578W. doi:10.1073/pnas.95.12.6578. PMC 33863. PMID 9618454.

- ^ Pace, Norman R. (18 May 2006). "Concept Time for a change" (PDF). Nature. 441 (7091): 289. Bibcode:2006Natur.441..289P. doi:10.1038/441289a. PMID 16710401. S2CID 4431143. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 October 2012. Retrieved 2 June 2012.

- ^ "Scientific background". The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 2009. Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences. Archived from the original on 2 April 2012. Retrieved 10 June 2012.

- ^ Nakano, A.; Luini, A. (2010). "Passage through the Golgi". Current Opinion in Cell Biology. 22 (4): 471–478. doi:10.1016/j.ceb.2010.05.003. PMID 20605430.

- ^ Panno, Joseph (2004). The Cell. Facts on File science library. Infobase Publishing. pp. 60–70. ISBN 978-0-8160-6736-7.

- ^ Alberts, Bruce; et al. (1994). "From Single Cells to Multicellular Organisms". Molecular Biology of the Cell (3rd ed.). New York: Garland Science. ISBN 978-0-8153-1620-6. Retrieved 12 June 2012.

- ^ Zimmer, Carl (7 January 2016). "Genetic Flip Helped Organisms Go From One Cell to Many". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 7 January 2016. Retrieved 7 January 2016.

- ^ Alberts, Bruce; et al. (2002). "General Principles of Cell Communication". Molecular Biology of the Cell. New York: Garland Science. ISBN 978-0-8153-3218-3. Archived from the original on 4 September 2015. Retrieved 12 June 2012.

- ^ Race, Margaret S.; Randolph, Richard O. (2002). "The need for operating guidelines and a decision making framework applicable to the discovery of non-intelligent extraterrestrial life". Advances in Space Research. 30 (6): 1583–1591. Bibcode:2002AdSpR..30.1583R. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.528.6507. doi:10.1016/S0273-1177(02)00478-7. ISSN 0273-1177.

There is growing scientific confidence that the discovery of extraterrestrial life in some form is nearly inevitable

- ^ Cantor, Matt (15 February 2009). "Alien Life 'Inevitable': Astronomer". Newser. Archived from the original on 23 May 2013. Retrieved 3 May 2013.

Scientists now believe there could be as many habitable planets in the cosmos as there are stars, and that makes life's existence elsewhere "inevitable" over billions of years, says one.

- ^ Schulze-Makuch, Dirk; Dohm, James M.; Fairén, Alberto G.; et al. (December 2005). "Venus, Mars, and the Ices on Mercury and the Moon: Astrobiological Implications and Proposed Mission Designs". Astrobiology. 5 (6): 778–795. Bibcode:2005AsBio...5..778S. doi:10.1089/ast.2005.5.778. PMID 16379531. S2CID 13539394. Archived from the original on 31 March 2021. Retrieved 13 December 2019.

- ^ Woo, Marcus (27 January 2015). "Why We're Looking for Alien Life on Moons, Not Just Planets". Wired. Archived from the original on 27 January 2015. Retrieved 27 January 2015.

- ^ Strain, Daniel (14 December 2009). "Icy moons of Saturn and Jupiter may have conditions needed for life". The University of Santa Cruz. Archived from the original on 31 December 2012. Retrieved 4 July 2012.

- ^ Baldwin, Emily (26 April 2012). "Lichen survives harsh Mars environment". Skymania News. Archived from the original on 28 May 2012. Retrieved 27 April 2012.

- ^ de Vera, J.-P.; Kohler, Ulrich (26 April 2012). "The adaptation potential of extremophiles to Martian surface conditions and its implication for the habitability of Mars" (PDF). EGU General Assembly Conference Abstracts. 14: 2113. Bibcode:2012EGUGA..14.2113D. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 May 2012. Retrieved 27 April 2012.

- ^ Selis, Frank (2006). "Habitability: the point of view of an astronomer". In Gargaud, Muriel; Martin, Hervé; Claeys, Philippe (eds.). Lectures in Astrobiology. Vol. 2. Springer. pp. 210–214. ISBN 978-3-540-33692-1.

- ^ Lineweaver, Charles H.; Fenner, Yeshe; Gibson, Brad K. (January 2004). "The Galactic Habitable Zone and the age distribution of complex life in the Milky Way". Science. 303 (5654): 59–62. arXiv:astro-ph/0401024. Bibcode:2004Sci...303...59L. doi:10.1126/science.1092322. PMID 14704421. S2CID 18140737. Archived from the original on 31 May 2020. Retrieved 30 August 2018.

- ^ Vakoch, Douglas A.; Harrison, Albert A. (2011). Civilizations beyond Earth: extraterrestrial life and society. Berghahn Series. Berghahn Books. pp. 37–41. ISBN 978-0-85745-211-5. Retrieved 25 August 2020.

- ^ Green, James; Hoehler, Tori; Neveu, Marc; Domagal-Goldman, Shawn; Scalice, Daniella; Voytek, Mary (27 October 2021). "Call for a framework for reporting evidence for life beyond Earth". Nature. 598 (7882): 575–579. arXiv:2107.10975. Bibcode:2021Natur.598..575G. doi:10.1038/s41586-021-03804-9. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 34707302. S2CID 236318566. Archived from the original on 1 November 2021. Retrieved 1 November 2021.

- ^ Fuge, Lauren (30 October 2021). "NASA proposes playbook for communicating the discovery of alien life – Sensationalising aliens is so 20th century, according to NASA scientists". Cosmos. Archived from the original on 31 October 2021. Retrieved 1 November 2021.

- ^ "Artificial life". Dictionary.com. Archived from the original on 16 November 2016. Retrieved 15 November 2016.

- ^ Chopra, Paras; Akhil Kamma. "Engineering life through Synthetic Biology". In Silico Biology. 6. Archived from the original on 5 August 2008. Retrieved 9 June 2008.

외부 링크

- Wiki species – 무료 생활 디렉토리

- 비태 (바이오리브)

- 바이오타(분류학 아이콘)

- 스탠퍼드 철학백과사전 수록