테스토스테론

Testosterone

| |

| |

| 이름 | |

|---|---|

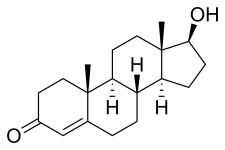

| IUPAC 이름 17β-히드록시안드로스트-4-en-3-One | |

| 우선 IUPAC 이름 (1S,3aS,3bR,9aR,9bS,11a)-1-히드록시-9a,11a-디메틸-1,2,3,3a,3b,4,5,8,9a,9b,10,11a-테트라데카히드로-7H펜타[시클렌타] | |

| 기타 이름 안드로스트-4-en-17β-ol-3-One | |

| 식별자 | |

3D 모델(JSmol) | |

| 체비 | |

| 첸블 | |

| 켐스파이더 | |

| 드러그뱅크 | |

| ECHA 정보 카드 | 100.000.336 |

| EC 번호 |

|

| 케그 | |

PubChem CID | |

| 유니 | |

CompTox 대시보드 (EPA ) | |

| |

| |

| 특성. | |

| C19H28O2 | |

| 몰 질량 | 288.431 g/120−1 |

| 녹는점 | 151.0°C(303.8°F, 424.1K)[1] |

| 약리학 | |

| G03BA03(WHO) | |

| 라이선스 데이터 | |

| 경피(겔, 크림, 용액, 패치), 구강(테스토스테론 운데칸산염), 볼에 있는 비강(겔), 근육 내 주입(에스테르), 피하 펠릿 | |

| 약동학: | |

| 경구: 매우 낮음(광범위한 퍼스트패스 대사 때문에) | |

| 97.0~99.5% (및 알부민)[2] | |

| 간(주로 환원 및 결합) | |

| 30~45분[citation needed] | |

| 소변(90%), 대변(6%) | |

달리 명시되지 않은 한 표준 상태(25°C[77°F], 100kPa)의 재료에 대한 데이터가 제공됩니다. | |

테스토스테론은 남성의 [3]주요 성호르몬이며 동화 스테로이드이다.인간에게서 테스토스테론은 고환과 전립선 같은 남성 생식조직의 발달과 근육과 뼈의 질량의 증가, 몸의 [4]털의 성장과 같은 2차 성징을 촉진하는 데 중요한 역할을 한다.또한 남녀 모두 테스토스테론은 기분, 행동, 골다공증 예방 [5][6]등 건강과 웰빙에 관여한다.남성의 테스토스테론 수치가 부족하면 허약함과 뼈 손실을 포함한 기형을 초래할 수 있다.

테스토스테론은 케톤과 수산기를 각각 위치 3과 17에 포함하는 안드로스테인류 스테로이드이다.그것은 콜레스테롤에서 여러 단계로 생합성되고 간에서 비활성 대사물로 [7]전환된다.안드로겐 [7]수용체와의 결합 및 활성화를 통해 그 작용을 발휘합니다.인간과 대부분의 다른 척추동물에서, 테스토스테론은 주로 수컷의 고환(생합성 참조)과 암컷의 난소에서 분비된다.평균적으로, 성인 남성의 테스토스테론 수치는 성인 여성의 [8]약 7~8배입니다.남성에서 테스토스테론의 신진대사가 활발해지면서 남성에서 하루 생산량이 [9][10]약 20배 정도 증가한다.암컷들은 [11]또한 호르몬에 더 민감하다.

테스토스테론은 자연 호르몬으로서의 역할 외에도 남성의 경우 저고나디즘, 여성의 [12]경우 유방암 치료에 약물로 사용된다.테스토스테론 수치가 나이가 들면서 감소하기 때문에, 테스토스테론은 때때로 나이 든 남성들에게 이 결핍을 상쇄하기 위해 사용된다.그것은 [13]또한 운동선수들에게서처럼 체격과 경기력을 향상시키기 위해 불법적으로 사용된다.세계반도핑기구는 S1 아나볼릭 물질로 "항상 금지"[14]되어 있다.

생물학적 영향

일반적으로 테스토스테론과 같은 안드로겐은 단백질 합성을 촉진하여 안드로겐 [15]수용체를 가진 조직의 성장을 촉진한다.테스토스테론은 남성화와 동화작용을 하는 것으로 묘사될 수 있다.[16]

- 동화 작용에는 근육량과 힘의 증가, 골밀도와 힘의 증가, 그리고 선형 성장과 뼈 성숙의 자극이 포함됩니다.

- 안드로겐 효과는 성기관, 특히 음경의 성숙과 태아의 음낭 형성, 그리고 출생 후(보통 사춘기에) 목소리의 깊어짐, 수염과 겨드랑이 털의 성장을 포함한다.이들 중 다수는 남성 2차 성징의 범주에 속합니다.

테스토스테론 효과는 또한 일반적인 발생 연령에 따라 분류될 수 있다.남성과 여성 모두에서 산후 효과를 위해, 이것들은 대부분 유리 테스토스테론의 순환 [citation needed]수준과 지속 시간에 의존합니다.

태어나기 전

출생 전 효과는 발달 단계에 따라 두 가지 범주로 분류된다.

첫 번째 시기는 임신 4주에서 6주 사이에 일어납니다.테스토스테론의 역할은 디히드로테스토스테론보다 훨씬 작지만, 중간선 융합, 남근 요도, 음낭의 얇음과 융기, 남근의 확대와 같은 생식기 남성화가 그 예이다.전립선과 정낭의 [citation needed]발달도 있다.

임신 2기 동안 안드로겐 수치는 성 [17]형성과 관련이 있다.특히 테스토스테론은 항뮬러 호르몬(AMH)과 함께 울프관의 성장과 뮐러관의 변성을 각각 [18]촉진한다.이 기간은 태아의 여성화 또는 남성화에 영향을 미치며 성인 자신의 수준보다 성 유형 행동과 같은 여성적이거나 남성적인 행동을 더 잘 예측할 수 있습니다.태아 안드로겐은 성별이 있는 활동에 대한 흥미와 참여에 영향을 미치고 공간적 [19]능력에 중간 정도의 영향을 미치는 것으로 보인다.CAH를 가진 여성들 사이에서, 어린 시절의 남성-일반적인 놀이는 여성 성별에 대한 만족도가 떨어지고 [20]성인기에 이성애적 관심이 감소하는 것과 관련이 있었다.

초기 유아기

초기 유아기 안드로겐 효과는 가장 잘 알려져 있지 않다.생후 첫 주에 남성 유아의 테스토스테론 수치가 상승합니다.그 수치는 몇 달 동안 사춘기 범위에 머무르지만, 보통 [21][22]생후 4-7개월이 되면 겨우 감지할 수 있는 어린 시절의 수준에 도달한다.인간의 이러한 상승의 기능은 알려지지 않았다.뇌의 남성화가 일어나는 것은 신체의 [23]다른 부분에서 중요한 변화가 확인되지 않았기 때문이라는 이론이 제기되어 왔다.남성 뇌는 테스토스테론이 에스트로겐으로 방향족화되면서 남성화되는데, 여성 태아는 에스트로겐을 결합시켜 여성의 뇌가 영향을 [24]받지 않도록 하는 α-페토프로틴을 가지고 있다.

사춘기 전

사춘기 전에는 안드로겐 수치 상승의 영향이 남녀 모두에게 나타난다.이것은 성인형 체취, 피부와 모발의 기름기 증가, 여드름, 치골(치아의 생김새), 겨드랑이 털,[25] 성장기, 뼈 성숙 가속, 그리고 얼굴 털을 포함합니다.

푸베르탈

사춘기 효과는 안드로겐이 몇 달 또는 몇 년 동안 정상적인 성인 여성 수치보다 높을 때 발생하기 시작한다.남성의 경우, 이것들은 보통 늦은 사춘기 효과이며, 혈액에서 유리 테스토스테론의 수치가 장기간 높아진 후 여성들에게서 발생합니다.효과는 다음과 같습니다.[25][26]

- 고환, 남성 생식력, 음경 또는 음핵 확대, 성욕 증가와 발기 또는 음핵 발기 빈도가 발생한다.

- 사람의 성장호르몬과 함께 턱, 눈썹, 턱, 코의 성장과 얼굴뼈 윤곽의 개조가 일어난다.[27]

- 뼈의 성숙과 성장의 종료.이것은 에스트라디올 대사물을 통해 간접적으로 발생하며, 따라서 여성보다 남성에서 더 점진적으로 발생한다.

- 근육의 힘과 질량의 증가, 어깨의 넓어짐, 늑골의 확장, 목소리의 깊어짐, 목젖의 성장.

- 피지선의 종대.이것은 여드름을 유발할 수 있고, 얼굴의 피하지방이 감소합니다.

- 치모는 허벅지까지 이어지며 배꼽까지 올라오고, 얼굴모발(구레나룻, 수염, 콧수염), 두피모발(안드로겐탈모), 가슴모발, 근막모발, 다리모발, 겨드랑이모발 등입니다.

성인

테스토스테론은 정상적인 정자 발달을 위해 필요하다.그것은 정조세포의 분화를 촉진하는 세르톨리 세포의 유전자를 활성화시킨다.우성 [28]도전 하에서 급성 HPA(최고 시상-하수체-부신 축) 반응을 조절한다.테스토스테론을 포함한 안드로겐은 근육 성장을 촉진합니다.테스토스테론은 또한 거핵구와 혈소판의 트롬복산A2 수용체 수를 조절하여 사람의 [29][30]혈소판 응집을 조절한다.

성인 테스토스테론의 효과는 여성보다 남성에게 더 뚜렷하게 나타나지만, 남녀 모두에게 중요하다.이러한 영향들 중 일부는 성인의 [31]삶의 후반 수십 년 동안 테스토스테론 수치가 감소할 수 있기 때문에 감소할 수 있다.

건강상의 리스크

테스토 스테론 전립선 암의 위험을 증가시키는 것 같지 않다.는 테스토 스테론 결핍 치료를 거쳐왔다 사람들은, 불알을 까다 수준을 넘는 테스토 스테론 증가 기존 전립선 암의 확산율을 높이도록 나타났습니다.[32][33][34]

상충되는 결과 테스토 스테론의 심혈관 건강을 유지하는 중요성에 관한 증서를 수령했다.[35][36]그럼에도 불구하고, 남성 노년층에서 정상적인 테스토 스테론 수준을 유지하는 증가된 무지방 신체 질량 감소하면서 내장 지방 질량 감소하면서 총 콜레스테롤, 혈당 관리 등 심혈관 질환 위험을 줄이는 것으로 생각됩니다 많은 매개 변수들을 개선하는 것으로 나타났다.[37]

높은 안드로겐 수치 모두 임상의 수가 줄고 건강한 여성에게는 생리 주기 비리와 관련되어 있다.[더 나은 공급원이 필요하][38]

성적 흥분

테스토 스테론 수준은 매일 일찍 일어나관계 없이 성관계의 peaksnycthemeral 리듬을 따른다.[39]

여성에서 긍정적인 오르가즘을 경험과 그 경험의 휴식이 핵심 지각 있는 테스토 스테론의 수치 사이에 긍정적인 상관 관계 있다.에는 테스토 스테론과 그들의 오르가슴을 경험의 남자들의 지각력, 그리고 또한 남녀에 더 높은 테스토 스테론 수준과 더 큰 남녀 자기 주장 사이에 아무런 상관 관계 사이에 아무런 상관 관계가 있다.[40]

여성의 성적 각성과 자위 테스토 스테론 농도가 조금만 증가를 생산한다.[41]자위 행위 후에도 남성 분들에 다양한 스테로이드제에 대한 혈장 수준 크게 증가 추세와 사람들이 테스토 스테론 수준은 수준으로 관련이 있다.[42]

포유류의 연구

쥐를 대상으로 실시된 연구는 그들의 성적 흥분 정도가 테스토스테론의 감소에 민감하다는 것을 보여준다.테스토스테론이 결핍된 쥐에게 중간 수준의 테스토스테론을 투여했을 때, 그들의 성적 행동(교배, 파트너 선호도 등)은 재개되었지만, 같은 호르몬의 양이 적을 때는 재개되지 않았다.따라서, 이러한 포유류는 저활동성 성욕 [43]장애와 같은 성적 각성 장애를 가진 인간의 임상 모집단을 연구하기 위한 모델을 제공할 수 있다.

조사된 모든 포유류 종들은 새로운 암컷을 만났을 때 수컷의 테스토스테론 수치가 현저하게 증가했음을 보여주었다.수컷 쥐의 반사적인 테스토스테론 증가는 수컷의 초기 성적 [44]흥분 수준과 관련이 있다.

인간이 아닌 영장류에서는 사춘기의 테스토스테론이 성적 각성을 자극하여 암컷과의 성적 경험을 점점 더 추구하게 하고,[45] 따라서 암컷에 대한 성적 선호도를 만들어 내는 것일 수 있습니다.일부 연구는 또한 성인 남성 인간이나 다른 성인 남성 영장류 시스템에서 테스토스테론이 제거되면 성적 동기가 감소하지만, 그에 상응하는 성적 활동 능력의 감소는 없다는 것을 보여 주었다.[45]

정자 경쟁 이론에 따르면, 테스토스테론 수치는 수컷 [46]쥐에서 성적인 상태가 되었을 때 이전에 중성이었던 자극에 대한 반응으로 증가하는 것으로 나타났습니다.이 반응은 짝짓기 만남에서 한 명 이상의 수컷이 있을 때 정자 경쟁을 돕는 음경 반사(발기 및 사정 등)를 수반하여 성공적인 정자의 생산과 더 높은 번식 가능성을 가능하게 합니다.

남성

남성들에게서, 더 높은 수준의 테스토스테론은 성활동 [47][48]기간과 관련이 있다.

성적으로 노골적인 영화를 보는 남성들은 평균 35%의 테스토스테론이 증가하여 영화 종료 후 60-90분에 정점을 찍지만, 성적으로 중립적인 영화를 [49]보는 남성들에게서는 증가하지 않는다.성적으로 노골적인 영화를 보는 남성들은 또한 동기부여, 경쟁력, 그리고 [50]피로감 감소를 보고한다.또한 성적 흥분과 테스토스테론 [51]수치를 따른 이완 사이의 연관성이 발견되었다.

남성들의 테스토스테론 수치는 그들이 배란성 여성의 체취에 노출되었는지 또는 비배란성 여성의 체취에 노출되었는지에 따라 달라진다.배란 여성의 향기에 노출된 남성들은 비배란 신호에 노출된 남성들의 테스토스테론 수치보다 높은 안정적인 테스토스테론 수치를 유지했다.남성들은 [52]여성의 호르몬 주기에 대해 매우 잘 알고 있다.이는 수컷이 가장 가임성이 높은 때를 감지하여 암컷의 배란 주기에 반응하도록 적응하고 암컷이 가장 가임성이 높을 때 선호하는 수컷 짝을 찾는 배란 이동 [53]가설과 관련이 있을 수 있다. 두 가지 행동 모두 호르몬에 의해 주도될 수 있다.

여성

안드로겐은 질 조직의 생리를 조절하고 여성 생식기 성적 [54]흥분에 기여할 수 있다.여성의 테스토스테론 수치는 성관계 전 대 성관계 전 대 성관계 전, 성관계 후 대 성관계 [55]후 측정했을 때 더 높습니다.여성의 생식기 각성에 테스토스테론을 투여하면 시차 효과가 있습니다.또한 질 성적 각성의 지속적인 증가는 생식기 감각과 성적 욕구를 유발하는 [56]결과를 초래할 수 있다.

여성의 테스토스테론 수치가 높을 때, 성적 각성 수치는 더 높지만 테스토스테론의 증가는 더 적으며, 이는 여성의 테스토스테론 수치에 대한 상한 효과를 나타냅니다.성적인 생각은 또한 여성 몸의 테스토스테론 수치를 변화시키지만 코티솔 수치는 변화시키지 않으며 호르몬 피임약은 성적인 [57]생각에 대한 테스토스테론 반응의 변화에 영향을 미칠 수 있다.

테스토스테론은 여성 성적 각성 [58]장애에서 효과적인 치료제이며 피부 패치로 사용할 수 있습니다.안드로겐 기능 부전 치료를 위한 FDA 승인 안드로겐 제제는 없지만, 노년 여성들에게 낮은 성욕과 성기능 장애를 치료하기 위한 오프 라벨 사용으로 사용되어 왔다.테스토스테론은 효과적으로 에스트로겐화 [58]되는 한 폐경 후 여성들에게 치료제가 될 수 있다.

연애 관계

사랑에 빠지는 것은 남성의 테스토스테론 수치 감소와 관련이 있는 반면 여성의 테스토스테론 [59]수치에는 혼합된 변화가 보고되었다.[60] 이러한 테스토스테론의 변화가 [60]성별 간의 행동 차이를 일시적으로 감소시키는 결과를 가져온다는 추측이 있었다.하지만,[59][60] 관찰된 테스토스테론 변화는 시간이 지남에 따라 관계가 발전함에 따라 유지되지 않는 것으로 보인다.

테스토스테론을 적게 생산하는 남성은 [62]연애나[61] 기혼일 가능성이 높고, 테스토스테론을 많이 생산하는 남성은 [62]이혼할 가능성이 높다.결혼이나 헌신은 테스토스테론 [63]수치를 감소시킬 수 있다.연애 경험이 없는 독신남성은 경험이 있는 독신남성에 비해 테스토스테론 수치가 낮다.경험이 있는 독신 남성들은 경험이 없는 [64]남성들보다 더 경쟁적인 상태에 있다는 것이 제안된다.배우자 및/또는 자녀와 하루를 보내는 것과 같은 유대 유지 활동을 하는 기혼 남성은 그러한 활동을 하지 않을 때와 비교해 테스토스테론 수치가 다르지 않다.종합적으로, 이러한 결과는 결합 유지 활동보다는 경쟁 활동의 존재가 테스토스테론 [65]수준의 변화와 더 관련이 있음을 시사한다.

더 많은 테스토스테론을 생성하는 남성들은 혼외 [62]성관계를 가질 가능성이 더 높다.테스토스테론 수치는 파트너의 신체적인 존재에 의존하지 않는다; 같은 도시와 장거리 연애를 하는 남성들의 테스토스테론 수치는 비슷하다.[61]신체적인 존재는 테스토스테론-파트너 상호작용을 위해 관계를 맺고 있는 여성들에게 요구될 수 있다. 같은 도시의 파트너 여성들은 장거리 파트너 [66]여성들보다 테스토스테론 수치가 낮다.

아버지 노릇

아버지의 역할은 남성들의 테스토스테론 수치를 감소시키고, 감소된 테스토스테론과 관련된 감정과 행동이 아버지의 보살핌을 촉진한다는 것을 암시합니다.동종 간호를 이용하는 인간과 다른 종에서, 자손에 대한 아버지의 투자는 두 부모가 동시에 여러 아이를 키울 수 있게 해주기 때문에 자손의 생존에 이롭다.이것은 그들의 자식들이 생존하고 번식할 가능성이 더 높기 때문에 부모의 생식력을 증가시킨다.부성 양육은 고품질 식품에 대한 접근성 증가와 신체적, 면역학적 [67]위협 감소로 인해 자손의 생존을 증가시킨다.이것은 특히 인간에게 유익하다. 왜냐하면 자손들은 오랜 기간 부모에게 의존하며 산모는 출산 [68]간격이 상대적으로 짧기 때문이다.

부성 양육의 정도는 문화마다 다르지만, 직접적인 양육에 대한 높은 투자는 일시적인 [69]변동뿐만 아니라 낮은 평균 테스토스테론 수치와 관련이 있는 것으로 보여져 왔다.예를 들어, 아이가 괴로워할 때 테스토스테론 수치가 변동하는 것은 아버지로서의 스타일을 나타내는 것으로 밝혀졌다.아기의 울음소리를 듣고 아버지의 테스토스테론 수치가 떨어진다면 아이에게 공감하고 있다는 뜻이다.이것은 [70]유아의 양육 행동과 더 나은 결과와 관련이 있다.

동기

테스토스테론 수치는 재무 [71][72]결정 과정에서 위험을 감수하는 데 중요한 역할을 한다.

공격성과 범죄성

대부분의 연구는 성인 범죄와 테스토스테론 사이의 연관성을 뒷받침한다.청소년 비행과 테스토스테론에 대한 거의 모든 연구는 중요하지 않다.대부분의 연구들은 또한 테스토스테론이 반사회적 행동과 알코올 중독과 같은 범죄와 관련된 행동이나 성격 특성과 관련이 있다는 것을 발견했다.더 일반적인 공격적 행동과 감정 그리고 테스토스테론의 관계에 대한 많은 연구들이 행해졌다.연구의 절반 정도가 관계를 발견했고 절반 가량은 [73]관계가 없는 것으로 나타났다.연구들은 또한 테스토스테론이 [74]시상하부에 있는 바소프레신 수용체를 조절함으로써 공격성을 촉진한다는 것을 발견했다.

공격성과 경쟁에서 [75]테스토스테론의 역할에 대한 두 가지 이론이 있다.첫 번째는 사춘기 동안 테스토스테론이 증가하여 [75]공격성을 포함한 생식 및 경쟁적인 행동을 촉진한다는 도전 가설입니다.그러므로 공격성과 [75]폭력을 조장하는 것은 그 종의 수컷들 사이의 경쟁의 도전이다.수행된 연구는 특히 테스토스테론 [75]수치가 가장 높은 교도소에서 가장 폭력적인 범죄자들 사이에서 테스토스테론과 지배력 사이의 직접적인 상관관계를 밝혀냈다.같은 연구는 또한 경쟁적인 환경 밖에 있는 아버지들이 다른 [75]남자들에 비해 테스토스테론 수치가 가장 낮다는 것을 발견했다.

두 번째 이론은 비슷하며 "진화 신경 안드로겐 남성 공격성 이론"[76][77]으로 알려져 있다.테스토스테론과 다른 안드로겐은 사람과 다른 사람들에게 해를 끼칠 위험이 있을 정도로까지 경쟁력을 갖추기 위해 뇌를 남성화하도록 진화해 왔다.그렇게 함으로써, 출생 전 및 성인의 삶의 테스토스테론 및 안드로겐의 결과로 남성화된 뇌를 가진 사람들은 가능한 [76]한 살아남고, 유혹하고, 짝짓기를 하기 위해 그들의 자원 획득 능력을 강화한다.뇌의 남성화는 성인의 테스토스테론 수치뿐만 아니라 태아로서의 자궁 내 테스토스테론 노출에 의해서도 매개된다.낮은 자릿수 비율과 성인 테스토스테론 수치로 나타나는 출생 전 테스토스테론이 높으면 축구 [78]경기에서 남성 선수들 사이에서 반칙이나 공격성의 위험이 증가했습니다.연구들은 또한 출생 전 테스토스테론이 높거나 낮은 자릿수 비율이 남성의 [79][80][81][82][83]공격성 증가와 관련이 있다는 것을 발견했다.

경기 중 테스토스테론 수치 상승은 남성에게 공격성을 예측했지만 [84]여성에게는 그렇지 않았다.권총과 실험 게임을 상호작용한 피실험자들은 테스토스테론과 공격성이 증가했다.[85]자연 선택은 남성들이 경쟁적이고 지위의 도전 상황에 더 민감하도록 진화시켰을 수 있으며 테스토스테론의 상호작용 역할이 이러한 상황에서 공격적인 [86]행동에 필수적인 요소이다.테스토스테론은 폭력적인 [87]자극에 대한 넓은 시야를 촉진함으로써 남성들에게 잔인하고 폭력적인 신호에 대한 매력을 매개한다.테스토스테론 특유의 구조적 뇌 특성은 [88]개인의 공격적인 행동을 예측할 수 있다.

테스토스테론은 공정한 행동을 장려할 수 있다.한 연구에서 피실험자들은 실제 돈의 분배가 결정되는 행동 실험에 참여했습니다.그 규칙은 공정한 제안과 부당한 제안을 모두 허용했다.협상 파트너는 이후 제안을 수락하거나 거절할 수 있습니다.제안이 공정할수록 협상 파트너의 거절 가능성은 낮아집니다.합의가 이루어지지 않으면 어느 쪽도 아무것도 얻지 못했다.인공적으로 강화된 테스토스테론 수치를 가진 실험 대상자들은 일반적으로 위약을 받은 사람들보다 더 좋고 공정한 제안을 했고, 따라서 그들의 제안을 거절할 위험을 최소한으로 줄였다.그 후의 2개의 연구에서, [89][90][91]이러한 결과가 실증적으로 확인되었습니다.그러나 테스토스테론이 높은 남성들은 최후통첩 [92]게임에서 훨씬 덜 관대했다.NY과학아카데미는 또한 아나볼릭 스테로이드 사용이 십대들에게 더 높다는 것을 발견했고,[93] 이것은 폭력 증가와 관련이 있었다.연구들은 또한 일부 [94]참가자들에게 언어적 공격성과 분노를 증가시키기 위해 테스토스테론을 투여한 것으로 밝혀졌습니다.

몇몇 연구는 테스토스테론 유도체 에스트라디올이 남성들의 [73][95][96][97]공격성에 중요한 역할을 할 수 있다는 것을 보여준다.에스트라디올은 수컷 [98]쥐의 공격성과 관련이 있는 것으로 알려져 있다.게다가 테스토스테론의 에스트라디올로의 전환은 번식기 [99]참새의 수컷 공격성을 조절한다.테스토스테론을 증가시키는 아나볼릭 스테로이드제를 투여받은 쥐들은 또한 "위협 민감성"[100]의 결과로 신체적으로 도발에 더 공격적이었다.

테스토스테론과 공격성 사이의 관계는 간접적으로도 기능할 수 있는데, 테스토스테론이 공격성 성향을 증폭시키는 것이 아니라 오히려 도전할 때 개인이 사회적 지위를 유지할 수 있는 성향을 증폭시키는 것이 제안되었기 때문입니다.대부분의 동물에서 공격성은 사회적 지위를 유지하는 수단이다.그러나 인간은 사회적 지위를 얻는 여러 가지 방법이 있다.이것은 왜 일부 연구가 친사회적 행동이 사회적 지위로 보상된다면 테스토스테론과 친사회적 행동 사이의 연관성을 발견하는지 설명할 수 있을 것이다.따라서 테스토스테론과 공격성, 폭력성 사이의 연관성은 사회적 [101]지위로 보상되기 때문입니다.그 관계는 또한 테스토스테론이 공격성 수준을 증가시키는 "허용 효과"의 하나일 수 있지만, 단지 평균 공격성 수준을 유지할 수 있다는 의미에서만; 화학적으로 또는 물리적으로 거세하는 것은 공격성 수준을 감소시킬 것이지만, 개인은 작은 수준만 필요로 합니다.테스토스테론이 추가되더라도 공격성 수준이 정상으로 돌아오도록 한다.테스토스테론은 또한 기존의 공격성을 과장하거나 증폭시킬 수도 있다; 예를 들어, 테스토스테론의 증가를 받은 침팬지는 사회적 서열에서 그들보다 낮은 침팬지에게는 더 공격적이 되지만 그들보다 높은 침팬지에게는 여전히 순종적일 것이다.따라서 테스토스테론은 침팬지를 무차별적으로 공격적으로 만드는 것이 아니라 하위 [102]침팬지에 대한 기존의 공격성을 증폭시킨다.

인간에게서 테스토스테론은 단순히 신체적 공격성을 증가시키기 보다는 신분추구와 사회적 지배력을 촉진하는 것으로 보인다.테스토스테론을 투여받았다는 믿음의 효과를 통제할 때, 테스토스테론을 투여받은 여성들은 테스토스테론을 [103]투여받지 않은 여성들보다 더 공정한 제안을 한다.

뇌

뇌는 또한 이러한 성적 [17]분화에 영향을 받습니다; 아로마타아제 효소는 테스토스테론을 수컷 생쥐에서 뇌의 남성화에 관여하는 에스트라디올로 변환합니다.인간의 경우 안드로겐 형성 또는 안드로겐 수용체 기능의 선천성 질환을 가진 환자의 성별 선호 관찰에 의해 태아 뇌의 남성화는 기능성 안드로겐 [104]수용체와 관련이 있는 것으로 나타난다.

남성과 여성의 뇌 사이에는 몇 가지 차이점이 있는데, 그 중 하나는 크기이다: 평균적으로 남성의 뇌가 더 [105]크다.남성의 경우 20세에 총 미엘리네이트 섬유 길이가 176,000km인 반면, 여성의 경우 총 길이가 149,000km([106]약 15%) 적었다.

43명의 건강한 [107]남성들에게 10주 동안 테스토스테론의 초생리학적 투여로 기분이나 행동에 즉각적인 단기적 영향은 발견되지 않았다.직업 선택에 있어서 테스토스테론과 위험 감수성 사이의 상관관계가 [71][108]여성들 사이에 존재한다.

주의력, 기억력, 공간 능력은 인간의 테스토스테론에 의해 영향을 받는 핵심 인지 기능이다.예비 증거는 낮은 테스토스테론 수치가 인지 저하와 알츠하이머 타입의 [109][110][111][112]치매에 대한 위험 요소일 수 있다는 것을 암시합니다. 이는 항노화 치료에서 테스토스테론의 사용에 대한 생명 연장 의학에서 중요한 주장입니다.그러나 대부분의 문헌은 순환 안드로겐의 저분비 및 과잉분비(결손 및 과잉분비)가 인지에 부정적인 영향을 미치는 공간적 성능과 순환 [113]테스토스테론 사이의 곡선 또는 고른 2차 관계를 제시한다.

면역체계와 염증

테스토스테론 결핍은 만성 [114]염증의 후유증인 대사 증후군, 심혈관 질환 및 사망률의 위험 증가와 관련이 있다.테스토스테론 혈장 농도는 CRP, 인터류킨 1 베타, 인터류킨 6, TNF 알파 및 엔도톡신 농도 및 백혈구 수를 [114]포함한 염증의 여러 바이오마커와 역상관한다.메타 분석에서 입증되었듯이, 테스토스테론 대체 요법은 염증 [114]마커를 유의하게 감소시킨다.이러한 효과는 시너지 [114]작용을 하는 다른 메커니즘에 의해 매개된다.안드로겐 결핍 남성에서 자가면역 갑상선염을 동반하는 테스토스테론 대체요법은 갑상선 자가항체 역가의 감소와 갑상선 분비 능력(SPINA-GT)[115]의 증가를 초래한다.

의료용

테스토스테론은 남성 저나드증, 성별 불감증, 그리고 특정 유형의 유방암을 [12][116]치료하기 위한 약물로 사용된다.이것은 혈청 테스토스테론 수치를 정상 범위로 유지하는 호르몬 대체 요법 또는 테스토스테론 대체 요법으로 알려져 있습니다.나이가 들면서 테스토스테론 생성의 감소는 안드로겐 대체 [117]요법에 대한 관심을 불러 일으켰다.노화로 인한 낮은 수준의 테스토스테론 사용이 이로운지 [118]해로운지는 불분명하다.

테스토스테론은 세계보건기구의 필수 의약품 목록에 포함되어 있는데, 이것은 기본적인 건강 [119]체계에 필요한 가장 중요한 의약품이다.제네릭 [12]의약품으로 구입할 수 있습니다.크림이나 경피용 패치로 피부에 바르거나, 근육에 주사하거나, 볼에 넣는 알약으로, 또는 [12]섭취로 투여할 수 있습니다.

테스토스테론 약물의 일반적인 부작용은 [12]남성의 여드름, 붓기, 유방확대 등이다.심각한 부작용에는 간 독성, 심장병, 그리고 행동 [12]변화가 포함될 수 있다.노출된 여성과 아이들은 남성화에 [12]걸릴 수 있다.전립선암에 걸린 사람은 그 약을 사용하지 않는 것이 좋습니다.[12]임신이나 수유 중에 사용하면 [12]해로울 수 있습니다.

미국내과대학(American College of Physicians)의 2020년 가이드라인은 성기능장애가 있는 연령과 관련된 낮은 수준의 테스토스테론을 가진 성인 남성에게 테스토스테론 치료에 대한 논의를 지지한다.그들은 가능한 개선과 관련하여 매년 평가를 하고 없다면 테스토스테론을 중단할 것을 권고한다. 의사들은 비용 및 두 방법의 효과와 해악이 비슷하기 때문에 경피 치료보다는 근육 내 치료를 고려해야 한다.성기능 장애의 가능한 개선 이외의 이유로 테스토스테론 치료를 [120][121]권장하지 않을 수 있습니다.

생물학적 활동

유리 테스토스테론

테스토스테론을 포함한 스테로이드 호르몬과 같은 친유성 호르몬은 특정 및 비특이적 단백질을 통해 수성 혈장에서 운반된다.특정 단백질은 테스토스테론, 디히드로테스토스테론, 에스트라디올, 그리고 다른 성 스테로이드와 결합하는 성호르몬 결합 글로불린을 포함한다.비특이적 결합단백질에는 알부민과 리포단백질이 포함된다.총 호르몬 농도 중 각각의 특정 캐리어 단백질에 결합되지 않은 부분은 유리 부분이다.그 결과, SHBG와 결합하지 않은 테스토스테론은 유리 테스토스테론이라고 불립니다.테스토스테론의 자유량만이 안드로겐 수용체에 결합할 수 있는 것으로 보이는데, 이것은 그들이 생물학적 [122]활동을 한다는 것을 의미한다.

스테로이드 호르몬 활성

인간과 다른 척추 동물에서 테스토스테론의 영향은 안드로겐 수용체의 활성화와 에스트라디올로의 전환과 특정 에스트로겐 [123][124]수용체의 활성화라는 여러 가지 메커니즘에 의해 발생합니다.테스토스테론과 같은 안드로겐은 또한 막 안드로겐 [125][126][127]수용체와 결합하고 활성화시키는 것으로 밝혀졌다.

유리테스토스테론(T)은 표적조직세포의 세포질로 운반되어 안드로겐 수용체에 결합하거나 세포질 효소 5α-환원효소에 의해 5α-디하이드로테스토스테론(DHT)으로 환원될 수 있다.DHT는 테스토스테론보다 더 강하게 같은 안드로겐 수용체에 결합하므로 안드로겐 효력은 [128]T의 약 5배이다.T 수용체 또는 DHT 수용체 복합체는 세포핵으로 이동하여 염색체 DNA의 특정 뉴클레오티드 배열에 직접 결합할 수 있는 구조적 변화를 겪는다.결합하는 영역은 호르몬 반응 요소라고 불리며, 안드로겐 효과를 생산하면서 특정 유전자의 전사 활동에 영향을 미친다.

안드로겐 수용체는 많은 다른 척추동물 체계의 조직에서 발생하며, 수컷과 암컷 모두 비슷한 수준에 반응한다.임신 전, 사춘기, 그리고 평생 동안 테스토스테론의 양이 크게 다른 것은 남성과 여성 사이의 생물학적 차이를 설명한다.

뼈와 뇌는 테스토스테론의 주된 효과가 에스트라디올에 대한 방향족화인 인간의 두 가지 중요한 조직이다.뼈에서 에스트라디올은 연골의 골화를 촉진시켜 후두엽의 폐쇄와 성장 종료를 가져온다.중추신경계에서 테스토스테론은 에스트라디올로 방향족화된다.테스토스테론 대신 에스트라디올은 시상하부에 대한 가장 중요한 피드백 신호로 작용합니다(특히 LH [129]분비에 영향을 줍니다).많은 포유동물에서, 태아기 또는 태아기가 테스토스테론 프로그램에서 파생된 에스트라디올에 의해 뇌의 성적 이형성 부위의 "마스크린화"[130]된다.

신경스테로이드 활성

테스토스테론은 활성 대사물 3α-androstanediol을 통해 GABAA [131]수용체의 잠재적인 양성 알로스테릭 조절제이다.

테스토스테론은 높은 친화력(약 5nM)[132][133][134]으로 신경트로핀 신경성장인자(NGF) 수용체인 TrkA와 p75의NTR 길항제 역할을 하는 것으로 밝혀졌다.테스토스테론과는 대조적으로 DHEA와 DHEA 황산염은 이들 [132][133][134]수용체의 고친화성 작용제로 작용하는 것으로 밝혀졌다.

테스토스테론은 시그마-1 수용체(Ki = 1,014 또는 201nM)[135]의 길항제이다.그러나 수용체 결합에 필요한 테스토스테론의 농도는 성인 남성의 총 순환 테스토스테론 농도(10~35nM)[136]를 훨씬 상회한다.

생화학

생합성

다른 스테로이드 호르몬처럼, 테스토스테론은 콜레스테롤에서 유래합니다.[138]생합성 첫 번째 단계는 콜레스테롤 측쇄분해효소(P450scc, CYP11A1)에 의한 콜레스테롤 측쇄의 산화분할을 포함한다.이 효소는 6개의 탄소 원자를 손실하여 프레그네놀론을 생성하는 미토콘드리아 시토크롬 P450 산화효소이다.다음 단계에서는 2개의 탄소원자를 내소체망 중 CYP17A1(17α-히드록실화효소/17,20-리아제) 효소에 의해 제거하여 다양한 C [139]스테로이드를 생성한다19.또한 3β-히드록시스테로이드탈수소효소에 의해 산화되어 안드로스테디온을 생성한다.C17 케토기 안드로스테니온을 17β-히드록시스테로이드탈수소효소 환원하여 테스토스테론을 생성한다.

가장 많은 양의 테스토스테론은 남성의 [4]고환에서 생성되며, 부신은 나머지 대부분을 차지한다.테스토스테론은 또한 여성에게서 부신, 난소의 흉골 세포, 그리고 임신 [140]중 태반에 의해 총량 훨씬 적은 양으로 합성된다.고환에서 테스토스테론은 레이디그 [141]세포에 의해 생성된다.남성 생식샘은 또한 정자 형성을 위해 테스토스테론을 필요로 하는 세르톨리 세포를 포함하고 있다.대부분의 호르몬과 마찬가지로 테스토스테론은 혈액 내 표적 조직에 공급되며, 이 조직의 대부분은 특정 혈장 단백질인 성호르몬 결합 글로불린(SHBG)과 결합되어 있다.

| 섹스. | 성호르몬 | 생식 기능 단계 | 피 생산율 | 생식선 분비율 | 대사 클리어런스 레이트 | 기준 범위(세럼 레벨) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SI 유닛 | 비유닛SI | ||||||

| 남자들 | 안드로스테디온 | – | 2.8 mg/일 | 1.6 mg/일 | 2,200 L/일 | 2.8~7.3 nmol/L | 80 ~ 210 ng/dL |

| 테스토스테론 | – | 6.5 mg/일 | 6.2mg/일 | 950 L/일 | 6.9~34.7 nmol/L | 200~1000ng/dL | |

| 에스트로네 | – | 150μg/일 | 110μg/일 | 2050 L/일 | 37 ~ 250 pmol / L | 10 ~ 70 pg / mL | |

| 에스트라디올 | – | 60μg/일 | 50μg/일 | 1,600 L/일 | 37~210 pmol/L 미만 | 10 ~ 57 pg / mL | |

| 황산에스트론 | – | 80μg/일 | 중요하지 않다 | 167 L/일 | 600 ~ 2,500 pmol / L | 200~900 pg/mL | |

| 여성들. | 안드로스테디온 | – | 3.2mg/일 | 2.8 mg/일 | 2,000 L/day | 3.1~12.2 nmol/L | 89~350 ng/dL |

| 테스토스테론 | – | 190μg/일 | 60μg/일 | 500 L/일 | 0.7~2.8 nmol/L | 20 ~ 81 ng/dL | |

| 에스트로네 | 엽상 | 110μg/일 | 80μg/일 | 2,200 L/일 | 110~400 pmol/L | 30~110 pg/mL | |

| 황체상 | 260μg/일 | 150μg/일 | 2,200 L/일 | 310 ~ 660 pmol / L | 80~180 pg/mL | ||

| 갱년기 후 | 40μg/일 | 중요하지 않다 | 1610 L/일 | 22 ~ 230 pmol / L | 6 ~ 60 pg / mL | ||

| 에스트라디올 | 엽상 | 90μg/일 | 80μg/일 | 1,200 L/일 | 37~360 pmol/L 미만 | 10 ~ 98 pg / mL | |

| 황체상 | 250μg/일 | 240μg/일 | 1,200 L/일 | 699 ~ 1250 pmol / L | 190 ~ 341 pg/mL | ||

| 갱년기 후 | 6μg/일 | 중요하지 않다 | 910 L/일 | 37~140 pmol/L 미만 | 10 ~ 38 pg / mL | ||

| 황산에스트론 | 엽상 | 100μg/일 | 중요하지 않다 | 146 L/일 | 700~3600 pmol/L | 250 ~ 1300 pg / mL | |

| 황체상 | 180μg/일 | 중요하지 않다 | 146 L/일 | 1100 ~ 7300 pmol / L | 400 ~ 2600 pg / mL | ||

| 프로게스테론 | 엽상 | 2 mg/일 | 1.7 mg/일 | 2100 L/일 | 0.3~3nmol/L | 0.1~0.9ng/mL | |

| 황체상 | 25 mg/일 | 24 mg/일 | 2100 L/일 | 19~45 nmol/L | 6~14 ng/mL | ||

메모 및 소스 주의: "순환 중 스테로이드 농도는 그것이 분비선에서 분비되는 속도, 전구체 또는 호르몬이 스테로이드로 대사되는 속도, 그리고 그것이 조직에 의해 추출되어 대사되는 속도에 의해 결정됩니다.스테로이드 분비율은 단위시간당 분비샘에서 분비되는 화합물의 총량을 말한다.분비율은 시간이 지남에 따라 분비샘에서 정맥 유출물을 추출하고 동맥 및 말초 정맥 호르몬 농도를 빼서 평가했습니다.스테로이드 대사 클리어런스율은 단위시간당 호르몬이 완전히 제거된 혈액의 양으로 정의된다.스테로이드 호르몬의 생산률은 분비선에서 나오는 분비물과 프로호르몬을 관심 스테로이드로 전환하는 것을 포함한 모든 가능한 원천에서 화합물의 혈액으로 들어가는 것을 말한다.정상 상태에서 모든 공급원에서 혈액으로 유입되는 호르몬의 양은 제거 속도(산출 속도=대사 제거 속도×농도)에 혈중 농도를 곱한 값과 같다.프로호르몬 대사가 스테로이드 순환 풀에 거의 기여하지 않으면 생산률은 분비율에 근접할 것입니다.출처:"템플릿"을 참조해 주세요. | |||||||

규정

남성에서 테스토스테론은 주로 레이디그 세포에서 합성된다.레이디지 세포의 수는 황체화 호르몬(LH)과 모낭자극 호르몬(FSH)에 의해 차례로 조절된다.또한 기존 레이디그 세포에서 생성되는 테스토스테론의 양은 17β-히드록시스테로이드 탈수소효소의 [142]발현을 조절하는 LH에 의해 제어된다.

합성되는 테스토스테론의 양은 시상하부-하수체-고환 축에 의해 조절된다(오른쪽 [143]그림 참조).테스토스테론 수치가 낮을 때 시상하부에서 고나도트로핀 방출 호르몬(GnRH)이 분비돼 뇌하수체가 FSH와 LH를 방출하도록 자극한다.이 두 호르몬은 고환을 자극하여 테스토스테론을 합성한다.마지막으로 음성 피드백 루프를 통한 테스토스테론 증가는 시상하부와 뇌하수체에 작용하여 각각 GnRH와 FSH/LH의 방출을 억제한다.

테스토스테론 수치에 영향을 미치는 요인은 다음과 같습니다.

- 연령: 테스토스테론 수치는 남성이 나이가 [144][145]들면서 점차 감소한다.이 효과는 때때로 안드로포즈 또는 후기성 [146]저고나디즘으로 언급된다.

- 연습:저항력 훈련은 테스토스테론 수치를 [147]급격히 증가시키지만, 나이 든 남성에게는 단백질 [148]섭취에 의해 그 증가를 피할 수 있다.남성들의 지구력 훈련은 테스토스테론 [149]수치를 낮추는 것으로 이어질 수 있다.

- 영양소:비타민 A 결핍은 차선의 혈장 테스토스테론 [150]수치로 이어질 수 있다.400–1000 IU/d(10–25 µg/d) 수준의 세코스테로이드 비타민 D는 테스토스테론 수치를 [151]높인다.아연 결핍은 테스토스테론[152] 수치를 낮추지만 과다 보충은 혈청 [153]테스토스테론에는 영향을 미치지 않는다.저지방 식단이 남성들의 [154]총 테스토스테론 수치를 감소시킬 수 있다는 제한된 증거가 있고, 매우 높은 단백질 식단이 남성들의 총 테스토스테론 수치를 감소시킨다는 중간 정도의 증거가 있다.[155]

- 체중 감소: 체중 감소는 테스토스테론 수치 증가를 초래할 수 있습니다.지방세포는 남성 성호르몬인 테스토스테론을 여성 [156]성호르몬인 에스트라디올로 바꾸는 아로마타아제 효소를 합성한다.그러나 체질량지수와 테스토스테론 수치 사이의 명확한 연관성은 [157]발견되지 않았다.

- 기타:수면: (렘 수면)은 야간 테스토스테론 [158]수치를 증가시킨다.동작:우위에 대한 도전은, 어떤 경우에는,[159] 남성들에게서 테스토스테론 분비를 증가시키는 것을 자극할 수 있다.약물: 스피어민트 차를 포함한 천연 또는 인공 항안드로겐은 테스토스테론 수치를 [160][161][162]낮춥니다.감초는 테스토스테론의 생성을 감소시킬 수 있고 이 효과는 [163]여성들에게 더 크다.

분배

테스토스테론의 혈장 단백질 결합은 98.0~98.5%, 유리 또는 [164]결합은 1.5~2.0%이다.그것은 성호르몬 결합 글로불린(SHBG)에 65%, [165]알부민에 약하게 결합되어 있다.

| 컴파운드 | 그룹. | 레벨(nM) | 무료(%) | SHBG (%) | CBG (%) | 알부민(%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 테스토스테론 | 성인 남성 | 23.0 | 2.23 | 44.3 | 3.56 | 49.9 |

| 성인 여성 | ||||||

| 엽상 | 1.3 | 1.36 | 66.0 | 2.26 | 30.4 | |

| 황체상 | 1.3 | 1.37 | 65.7 | 2.20 | 30.7 | |

| 임신 | 4.7 | 0.23 | 95.4 | 0.82 | 3.6 | |

| 디히드로테스토스테론 | 성인 남성 | 1.70 | 0.88 | 49.7 | 0.22 | 39.2 |

| 성인 여성 | ||||||

| 엽상 | 0.65 | 0.47 | 78.4 | 0.12 | 21.0 | |

| 황체상 | 0.65 | 0.48 | 78.1 | 0.12 | 21.3 | |

| 임신 | 0.93 | 0.07 | 97.8 | 0.04 | 21.2 | |

| 출처:"템플릿"을 참조해 주세요. | ||||||

대사

테스토스테론과 5α-DHT는 모두 [2][166]간에서 주로 대사된다.테스토스테론의 약 50%는 테스토스테론 글루쿠로니드로의 결합을 통해 대사되며, 테스토스테론 황산염은 글루쿠로노실전달효소 및 술포트전달효소에 의해 각각 [2]대사된다.테스토스테론의 40%는 5α- 및 5β-환원효소, 3α-히드록시스테로이드탈수소효소 및 17β-HSD의 조합작용을 [2][166][167]통해 17-케토스테로이드 안드로스테론 및 에티오콜라놀론으로 동일한 비율로 대사된다.다음으로 안드로스테론 및 에티오콜라놀론은 글루쿠론화되며 [2][166]테스토스테론과 유사하게 덜 황산된다.테스토스테론과 그 간 대사물의 결합체는 간에서 순환으로 방출되어 소변과 [2][166][167]담즙으로 배설된다.소량의 테스토스테론(2%)만이 [166]소변에서 변하지 않고 배설된다.

테스토스테론 대사의 간 17-케토스테로이드 경로에서 테스토스테론은 [2][166]간에서 각각 5α-환원효소 및 5β-환원효소에 의해 5α-DHT 및 불활성 5β-DHT로 변환된다.다음으로 5α-DHT와 5β-DHT를 각각 [2][166]3α-안드로스타네디올과 3α-에티오콜라네디올로 변환한다.이어서 3α-안드로스타니올 및 3α-에티오콜란디올을 17β-HSD에 의해 안드로스테론 및 에티오콜란올론으로 변환하고 이어서 이들의 결합 및 [2][166]배설한다.또한 3α-HSD가 아닌 3β-HSD에 의해 5α-DHT 및 5β-DHT가 작용하여 각각 에피안드로스테론 및 에피티오콜라놀론으로 [168][169]변환될 수 있다.테스토스테론의 약 3% 중 소량은 간에서 안드로스테디온으로 17β-HSD에 [167]의해 가역적으로 전환된다.

결합 및 17-케토스테로이드 경로와 더불어 테스토스테론은 CYP3A4, CYP3A5, CYP2C9, CYP2C19 및 CYP2D6.[170]6β-히드록시 등 시토크롬 P450 효소에 의해 간에서 수산화 및 산화될 수 있다.테스토스테론의 6β-히드록실화는 주로 CYP3A4에 의해 촉매되며, CYP3A5는 시토크롬 P450 매개 테스토스테론 [170]대사의 75~80%를 담당한다.또한 6β- 및 16β-히드록시테스토스테론 외에 1β-, 2α/β-, 11β- 및 15β-히드록시테스토스테론을 미량 [170][171]대사물로 형성한다.또한 CYP2C9 및 CYP2C19와 같은 특정 시토크롬 P450 효소는 C17 위치에서 테스토스테론을 산화시켜 안드로스테디온을 [170]형성할 수 있다.

테스토스테론의 직접적인 대사물 중 두 가지인 5α-DHT와 에스트라디올은 생물학적으로 중요하며 간과 간외 [166]조직 모두에서 형성될 수 있다.테스토스테론의 약 5~7%는 5α-환원효소에 의해 5α-DHT로 전환되고, 순환수준은 5α-DHT로 전환되며, 테스토스테론의 약 0.3%는 아로마타아제에 [4][166][172][173]의해 에스트라디올로 전환된다.5α-환원효소는 남성 생식기관(전립선, 정소포,[174] 부고환 포함), 피부, 모낭, 뇌[175], 방향화효소는 지방조직, 뼈, [176][177]뇌에서 많이 발현된다.테스토스테론의 90%가 높은 5α-환원효소 [167]발현을 가진 이른바 안드로겐 조직에서 5α-DHT로 전환되며, 테스토스테론에 [178]비해 AR 작용제로서의 5α-DHT의 효력이 몇 배 더 높기 때문에 테스토스테론의 효과가 2~3배 [179]더 증강되는 것으로 추정되었다.

레벨

체내 테스토스테론의 총 수치는 19세에서 39세 [180]사이의 비-비만 유럽 및 미국 남성의 경우 264에서 916ng/dL([181]데시리터당 나노그램)로 보고되었으며, 성인 남성의 평균 테스토스테론 수치는 630ng/dL로 보고되었다.일반적으로 [182]기준 범위로 사용되지만, 일부 의사들은 이 범위를 사용하여 저고나디즘을 결정하는 [183][184]것에 대해 이의를 제기했습니다.몇몇 전문 의료 그룹은 일반적으로 350ng/dl을 최소 정상 [185]수준으로 간주할 것을 권고했다. 이는 이전 [186][non-primary source needed][medical citation needed]조사 결과와 일치한다.남성의 테스토스테론 수치는 나이가 [180]들수록 감소한다.여성의 경우, 총 테스토스테론의 평균 수치는 32.6ng/[187][188]dL로 보고되었다.과안드로겐증을 가진 여성의 경우, 총 테스토스테론의 평균 수치는 62.1ng/[187][188]dL로 보고되었다.

| 총테스토스테론 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 단계. | 연령대 | 남자 | 여자 | ||

| 가치 | SI 유닛 | 가치 | SI 유닛 | ||

| 유아 | 시기상조(26~28주) | 59~125ng/dl | 2.047~4.337 nmol/L | 5~16ng/dl | 0.173~0.555 nmol/L |

| 시기상조(31~35주) | 37 ~ 1024 ng/dl | 1.284~6.871 nmol/L | 5~22ng/dl | 0.173~0.763 nmol/L | |

| 신생아 | 75~400ng/dl | 2.602~13.877 nmol/L | 20~64ng/dl | 0.694~2.220 nmol/L | |

| 어린아이 | 1~6년 | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| 7~9년 | 0~8ng/dl | 0 ~ 0.277 nmol/L | 1~12ng/dl | 0.035~0.416 nmol/L | |

| 사춘기 직전에 | 3~10ng/dL* | 0.14~0.347 nmol/L* | 10 ng/d 미만L* | 0.347 nmol/L* 미만 | |

| 사춘기 | 10~11년 | 1~48ng/dl | 0.035~1.666 nmol/L | 2 ~ 35 ng/dl | 0.069~1.214 nmol/L |

| 12~13년 | 5~619ng/dl | 0.173~21.480 nmol/L | 5~53ng/dl | 0.173~1.839 nmol/L | |

| 14~15년 | 100~320ng/dl | 3.47~11.10 nmol/L | 8~41 ng/dl | 0.278~1.423 nmol/L | |

| 16~17년 | 200 ~ 970 ng/dL* | 6.94~33.66 nmol/L* | 8 ~ 53 ng/dl | 0.278~1.839 nmol/L | |

| 어른 | years18년 | 350~1080 ng/dL* | 12.15 ~ 37.48 nmol/L* | – | – |

| 20~39년 | 400~1080 ng/dl | 13.88 ~ 37.48 nmol/L | – | – | |

| 40~59년 | 350~890 ng/dl | 12.15~30.88 nmol/L | – | – | |

| 60년 이내 | 350 ~ 1024 ng/dl | 12.15~24.98 nmol/L | – | – | |

| 폐경 전 | – | – | 10 ~ 54 ng/dl | 0.347~1.873 nmol/L | |

| 폐경 후 | – | – | 7~40ng/dl | 0.243~1.388 nmol/L | |

| 생체 가용 테스토스테론 | |||||

| 단계. | 연령대 | 남자 | 여자 | ||

| 가치 | SI 유닛 | 가치 | SI 유닛 | ||

| 어린아이 | 1~6년 | 0.2~1.3ng/dl | 0.007~0.045 nmol/L | 0.2~1.3ng/dl | 0.007~0.045 nmol/L |

| 7~9년 | 0.2~2.3ng/dl | 0.007 ~ 0.079 nmol/L | 0.2~4.2ng/dl | 0.007~0.146 nmol/L | |

| 사춘기 | 10~11년 | 0.2~14.8ng/dl | 0.007~0.513 nmol/L | 0.4~19.3ng/dl | 0.014~0.670 nmol/L |

| 12~13년 | 0.3~232.8ng/dl | 0.010~8.082 nmol/L | 1.1~15.6ng/dl | 0.038~0.541 nmol/L | |

| 14~15년 | 7.9~274.5ng/dl | 0.274~9.525 nmol/L | 2.5~18.8ng/dl | 0.087~0.652 nmol/L | |

| 16~17년 | 24.1 ~ 416.5 ng/dl | 0.836~14.452 nmol/L | 2.7~23.8ng/dl | 0.094~0.826 nmol/L | |

| 어른 | years18년 | ND | ND | – | – |

| 폐경 전 | – | – | 1.9~22.8ng/dl | 0.066~0.791 nmol/L | |

| 폐경 후 | – | – | 1.6~19.1ng/dl | 0.055~0.662 nmol/L | |

| 유리 테스토스테론 | |||||

| 단계. | 연령대 | 남자 | 여자 | ||

| 가치 | SI 유닛 | 가치 | SI 유닛 | ||

| 어린아이 | 1~6년 | 0.1~0.6 pg/ml | 0.3~2.1pmol/L | 0.1~0.6 pg/ml | 0.3~2.1pmol/L |

| 7~9년 | 0.1~0.8 페이지/ml | 0.3~2.8pmol/L | 0.1~1.6 pg/ml | 0.3~5.6pmol/L | |

| 사춘기 | 10~11년 | 0.1~5.2 페이지/ml | 0.3~18.0pmol/L | 0.1~2.9 페이지/ml | 0.3~10.1pmol/L |

| 12~13년 | 0.4~79.6 페이지/ml | 1.4~276.2pmol/L | 0.6~5.6 페이지/ml | 2.1~19.4 pmol/L | |

| 14~15년 | 2.7~112.3 페이지/ml | 9.4 ~ 389.7 pmol/L | 1.0~6.2 페이지/ml | 3.5~21.5pmol/L | |

| 16~17년 | 31.5~159 페이지/ml | 109.3 ~551.7 pmol/L | 1.0~8.3 페이지/ml | 3.5~28.8pmol/L | |

| 어른 | years18년 | 44~244 pg/ml | 153~847 pmol/L | – | – |

| 폐경 전 | – | – | 0.8~9.2 페이지/ml | 2.8~31.9 pmol/L | |

| 폐경 후 | – | – | 0.6~6.7 페이지/ml | 2.1~23.2pmol/L | |

| 출처:"템플릿"을 참조해 주세요. | |||||

| 라이프 스테이지 | 태너 단계 | 연령대 | 평균 연령 | 레벨 범위 | 평균 수준 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 어린아이 | 스테이지 1 | 10년 미만 | – | 30ng/d 미만l | 5.8 ng/dL |

| 사춘기 | 스테이지 II | 10~14년 | 12년 | <104 ng/dl | 40 ng/dL |

| 스테이지 III | 12~16년 | 13~14년 | 21~719ng/dl | 190 ng/dL | |

| 스테이지 IV | 13~17년 | 14~15년 | 25~912 ng/dl | 370 ng/dL | |

| 스테이지 V | 13~17년 | 15년 | 110 ~ 975 ng/dl | 550 ng/dL | |

| 어른 | – | years18년 | – | 250 ~ 1,100 ng/dl | 630 ng/dL |

| 출처: [189][190][181][191][192] | |||||

측정.

테스토스테론의 생체 가용 농도는 일반적으로 Vermeulen 계산 또는 성호르몬 결합 글로불린의 [195]이합체 형태를 고려하는 변형 Vermeulen [193][194]방법을 사용하여 결정된다.

두 방법 모두 생물학적 가용 테스토스테론의 농도를 도출하기 위해 화학적 평형을 사용합니다: 순환 중인 테스토스테론은 알부민(약하게 결합)과 성호르몬 결합 글로불린(강하게 결합)이라는 두 가지 주요 결합 파트너를 가지고 있습니다.이러한 방법은 첨부 그림에 자세히 설명되어 있습니다.

역사

고환 작용은 Arnold Adolph Berthold (1803–1861)[196]의 가금류 거세 및 고환 이식에 대한 초기 연구에서 순환 혈액 분율과 관련이 있었다.테스토스테론의 작용에 대한 연구는 1889년, 하버드 교수 샤를 에두아르 브라운 세콰르 (1817–1894)가 당시 파리에서 개와 기니피그 고환의 추출물로 구성된 "회생하는 약"을 피하에 주입했을 때, 잠깐 힘을 받았다.그는 랜싯에서 그의 원기 왕성함과 행복감은 눈에 띄게 회복되었지만 효과는 [197]일시적이었으며 브라운 세콰드의 화합물에 대한 희망은 무너졌다고 보도했다.동료들의 조롱에 시달리던 그는 인간 내 안드로겐의 메커니즘과 효과에 대한 연구를 포기했다.

1927년, 시카고 대학의 생리학 화학 교수 프레드 C.Koch는 많은 소의 고환(시카고 가축 사육장)에 쉽게 접근할 수 있도록 했으며 격리된 소를 추출하는 지루한 작업을 기꺼이 견딜 수 있는 학생들을 모집했다.그 해에 코흐와 그의 제자 레무엘 맥기(Lemuel McGee)는 40파운드의 소 고환을 공급받아 20mg의 물질을 추출했는데, 이 물질을 거세된 수탉, 돼지, 쥐에 투여했을 때, 그것들을 [198]재멸종시켰다.암스테르담 대학의 에른스트 라쿠르 그룹은 1934년 유사한 방법으로 소 고환에서 테스토스테론을 정제했지만, 인간의 심각한 연구를 허용하는 양으로 동물 조직으로부터 호르몬의 분리는 세 유럽의 거대 제약회사 – Schering (베를린, 독일), Organon (네덜란드), 그리고 Organon (Os, 네덜란드)까지 가능하지 않았다.시바(스위스 바젤)—1930년대에 스테로이드 연구 개발 프로그램을 본격화했다.

네덜란드의 오르가논 그룹은 1935년 5월 "고환의 결정성 남성 호르몬에 대하여"[199]라는 논문에서 확인된 이 호르몬을 최초로 분리한 그룹이었다.그들은 고환과 스테롤의 줄기와 케톤이라는 접미사를 따서 테스토스테론이라는 호르몬을 명명했다.이 구조는 그단스크에 [200][201]있는 Chemisches Institut of Technical University의 Schering의 Adolf Butenandt에 의해 고안되었습니다.

콜레스테롤로부터 테스토스테론의 화학적 합성은 부테난트와 하니쉬에 [202]의해 그 해 8월에 이루어졌다.불과 일주일 후 취리히의 시바 그룹, 레오폴드 루지카 (1887–1976)와 A.웨트스타인이 테스토스테론 [203]합성을 발표했어요콜레스테롤 베이스로부터 테스토스테론의 독립적인 부분 합성물은 부테난트와 루지카 둘 다 1939년 노벨 [201][204]화학상을 공동 수상했습니다.테스토스테론은 17번째 탄소 원자에서 수산기를 가진 고체 다환 알코올인 17β-히드록시앤드로스트-4-en-3-One(CHO)로19282 확인되었다.이것은 또한 합성된 테스토스테론의 추가 수정, 즉 에스테르화와 알킬화를 할 수 있다는 것을 분명히 했다.

그래서 Kochakian과 Murlin(1936년) 후 앨런 케년의 group[205]둘 다 anabol을 보여 줄 수 있었던 것 테스토 스테론이 개에게, 질소 축적율( 있는 메커니즘을 동화 작용에 중심)을 제기했다 보여 줄 수 있었다 풍부한, 강력한 테스토 스테론 에스테르의 1930년대에 부분 합성, 호르몬의 효과를 특성화 결국 허락하였다.제가 할 수 있어요.남성, 소년, 여성 내시노이드에서 프로피온산 테스토스테론의 안드로겐 효과1930년대 초반부터 1950년대까지 스테로이드 [206]화학의 황금기로 불렸고, 이 기간 동안의 작업은 [207]빠르게 진행되었다.

기타종

테스토스테론은 대부분의 척추동물에서 관찰된다.테스토스테론과 고전적인 핵 안드로겐 수용체는 처음 gnathostome(턱이 있는 척추동물)[208]에서 나타났다.칠성장어 같은 아그나탄(무족 척추동물)은 테스토스테론을 생성하지 않고 안드로스테디온을 남성 호르몬으로 [209]사용한다.물고기는 11-케토테스토스테론이라고 [210]불리는 약간 다른 형태를 만듭니다.곤충에 대응하는 것은 엑디손이다.[211]광범위한 동물에서 이러한 유비쿼터스 스테로이드제의 존재는 성호르몬이 고대의 진화 [212]역사를 가지고 있다는 것을 암시한다.

「 」를 참조해 주세요.

레퍼런스

- ^ Haynes WM, ed. (2011). CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (92nd ed.). CRC Press. p. 3.304. ISBN 978-1439855119.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Melmed S, Polonsky KD, Larsen PR, Kronenberg HM (November 30, 2015). Williams Textbook of Endocrinology. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 711–. ISBN 978-0-323-29738-7.

- ^ "Understanding the risks of performance-enhancing drugs". Mayo Clinic. Retrieved December 30, 2019.

- ^ a b c Mooradian AD, Morley JE, Korenman SG (February 1987). "Biological actions of androgens". Endocrine Reviews. 8 (1): 1–28. doi:10.1210/edrv-8-1-1. PMID 3549275.

- ^ Bassil N, Alkaade S, Morley JE (June 2009). "The benefits and risks of testosterone replacement therapy: a review". Therapeutics and Clinical Risk Management. 5 (3): 427–48. doi:10.2147/tcrm.s3025. PMC 2701485. PMID 19707253.

- ^ Tuck SP, Francis RM (2009). "Testosterone, bone and osteoporosis". Advances in the Management of Testosterone Deficiency. Frontiers of Hormone Research. Vol. 37. pp. 123–32. doi:10.1159/000176049. ISBN 978-3-8055-8622-1. PMID 19011293.

- ^ a b Luetjens CM, Weinbauer GF (2012). "Chapter 2: Testosterone: Biosynthesis, transport, metabolism and (non-genomic) actions". In Nieschlag E, Behre HM, Nieschlag S (eds.). Testosterone: Action, Deficiency, Substitution (4th ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 15–32. ISBN 978-1-107-01290-5.

- ^ Torjesen PA, Sandnes L (March 2004). "Serum testosterone in women as measured by an automated immunoassay and a RIA". Clinical Chemistry. 50 (3): 678, author reply 678–9. doi:10.1373/clinchem.2003.027565. PMID 14981046.

- ^ Southren AL, Gordon GG, Tochimoto S, Pinzon G, Lane DR, Stypulkowski W (May 1967). "Mean plasma concentration, metabolic clearance and basal plasma production rates of testosterone in normal young men and women using a constant infusion procedure: effect of time of day and plasma concentration on the metabolic clearance rate of testosterone". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 27 (5): 686–94. doi:10.1210/jcem-27-5-686. PMID 6025472.

- ^ Southren AL, Tochimoto S, Carmody NC, Isurugi K (November 1965). "Plasma production rates of testosterone in normal adult men and women and in patients with the syndrome of feminizing testes". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 25 (11): 1441–50. doi:10.1210/jcem-25-11-1441. PMID 5843701.

- ^ Dabbs M, Dabbs JM (2000). Heroes, rogues, and lovers: testosterone and behavior. New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-135739-5.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Testosterone". Drugs.com. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. December 4, 2015. Archived from the original on August 20, 2016. Retrieved September 3, 2016.

- ^ Liverman CT, Blazer DG, et al. (Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Assessing the Need for Clinical Trials of Testosterone Replacement Therapy) (2004). "Introduction". Testosterone and Aging: Clinical Research Directions (Report). National Academies Press (US).

- ^ "What is Prohibited". World Anti-Doping Agency. Archived from the original on November 12, 2020. Retrieved July 18, 2021.

- ^ Sheffield-Moore M (2000). "Androgens and the control of skeletal muscle protein synthesis". Annals of Medicine. 32 (3): 181–6. doi:10.3109/07853890008998825. PMID 10821325. S2CID 32366484.

- ^ Handelsman DJ (January 2013). "Androgen Physiology, Pharmacology and Abuse". Endotext [Internet]. WWW.ENDOTEXT.ORG. MDText.com, Inc.

- ^ a b Swaab DF, Garcia-Falgueras A (2009). "Sexual differentiation of the human brain in relation to gender identity and sexual orientation". Functional Neurology. 24 (1): 17–28. PMID 19403051.

- ^ Xu HY, Zhang HX, Xiao Z, Qiao J, Li R (2019). "Regulation of anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH) in males and the associations of serum AMH with the disorders of male fertility". Asian Journal of Andrology. 21 (2): 109–114. doi:10.4103/aja.aja_83_18. PMC 6413543. PMID 30381580.

- ^ Berenbaum SA (March 2018). "Beyond Pink and Blue: The Complexity of Early Androgen Effects on Gender Development". Child Development Perspectives. 12 (1): 58–64. doi:10.1111/cdep.12261. PMC 5935256. PMID 29736184.

- ^ Hines M, Brook C, Conway GS (February 2004). "Androgen and psychosexual development: core gender identity, sexual orientation and recalled childhood gender role behavior in women and men with congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH)". Journal of Sex Research. 41 (1): 75–81. doi:10.1080/00224490409552215. PMID 15216426. S2CID 33519930.

- ^ Forest MG, Cathiard AM, Bertrand JA (July 1973). "Evidence of testicular activity in early infancy". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 37 (1): 148–51. doi:10.1210/jcem-37-1-148. PMID 4715291.

- ^ Corbier P, Edwards DA, Roffi J (1992). "The neonatal testosterone surge: a comparative study". Archives Internationales de Physiologie, de Biochimie et de Biophysique. 100 (2): 127–31. doi:10.3109/13813459209035274. PMID 1379488.

- ^ Dakin CL, Wilson CA, Kalló I, Coen CW, Davies DC (May 2008). "Neonatal stimulation of 5-HT(2) receptors reduces androgen receptor expression in the rat anteroventral periventricular nucleus and sexually dimorphic preoptic area". The European Journal of Neuroscience. 27 (9): 2473–80. doi:10.1111/j.1460-9568.2008.06216.x. PMID 18445234. S2CID 23978105.

- ^ Kalat JW (2009). "Reproductive behaviors". Biological psychology. Belmont, Calif: Wadsworth, Cengage Learning. p. 321. ISBN 978-0-495-60300-9.

- ^ a b Pinyerd B, Zipf WB (2005). "Puberty-timing is everything!". Journal of Pediatric Nursing. 20 (2): 75–82. doi:10.1016/j.pedn.2004.12.011. PMID 15815567.

- ^ Barrett KE, Ganong WF (2012). Ganong's Review of Medical Physiology (24 ed.). TATA McGRAW Hill. pp. 423–25. ISBN 978-1-25-902753-6.

- ^ Raggatt LJ, Partridge NC (2010). "Cellular and molecular mechanisms of bone remodeling". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 285 (33): 25103–8. doi:10.1074/jbc.R109.041087. PMC 2919071. PMID 20501658.

- ^ Mehta PH, Jones AC, Josephs RA (June 2008). "The social endocrinology of dominance: basal testosterone predicts cortisol changes and behavior following victory and defeat" (PDF). Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 94 (6): 1078–93. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.336.2502. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.94.6.1078. PMID 18505319. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 19, 2009.

- ^ Ajayi AA, Halushka PV (May 2005). "Castration reduces platelet thromboxane A2 receptor density and aggregability". QJM. 98 (5): 349–56. doi:10.1093/qjmed/hci054. PMID 15820970.

- ^ Ajayi AA, Mathur R, Halushka PV (June 1995). "Testosterone increases human platelet thromboxane A2 receptor density and aggregation responses". Circulation. 91 (11): 2742–7. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.91.11.2742. PMID 7758179.

- ^ Kelsey TW, Li LQ, Mitchell RT, Whelan A, Anderson RA, Wallace WH (October 8, 2014). "A validated age-related normative model for male total testosterone shows increasing variance but no decline after age 40 years". PLOS ONE. 9 (10): e109346. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...9j9346K. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0109346. PMC 4190174. PMID 25295520.

- ^ Morgentaler A, Schulman C (2009). "Testosterone and prostate safety". Advances in the Management of Testosterone Deficiency. Frontiers of Hormone Research. Vol. 37. pp. 197–203. doi:10.1159/000176054. ISBN 978-3-8055-8622-1. PMID 19011298.

- ^ Rhoden EL, Averbeck MA, Teloken PE (September 2008). "Androgen replacement in men undergoing treatment for prostate cancer". The Journal of Sexual Medicine. 5 (9): 2202–08. doi:10.1111/j.1743-6109.2008.00925.x. PMID 18638000.

- ^ Morgentaler A, Traish AM (February 2009). "Shifting the paradigm of testosterone and prostate cancer: the saturation model and the limits of androgen-dependent growth". European Urology. 55 (2): 310–20. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2008.09.024. PMID 18838208.

- ^ Haddad RM, Kennedy CC, Caples SM, Tracz MJ, Boloña ER, Sideras K, Uraga MV, Erwin PJ, Montori VM (January 2007). "Testosterone and cardiovascular risk in men: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials". Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 82 (1): 29–39. doi:10.4065/82.1.29. PMID 17285783.

- ^ Jones TH, Saad F (December 2009). "The effects of testosterone on risk factors for, and the mediators of, the atherosclerotic process". Atherosclerosis. 207 (2): 318–27. doi:10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2009.04.016. PMID 19464009.

- ^ Stanworth RD, Jones TH (2008). "Testosterone for the aging male; current evidence and recommended practice". Clinical Interventions in Aging. 3 (1): 25–44. doi:10.2147/CIA.S190. PMC 2544367. PMID 18488876.

- ^ Van Anders SM, Watson NV (2006). "Menstrual cycle irregularities are associated with testosterone levels in healthy premenopausal women" (PDF). American Journal of Human Biology. 18 (6): 841–44. doi:10.1002/ajhb.20555. hdl:2027.42/83925. PMID 17039468. S2CID 32023452.

- ^ Fox CA, Ismail AA, Love DN, Kirkham KE, Loraine JA (January 1972). "Studies on the relationship between plasma testosterone levels and human sexual activity". The Journal of Endocrinology. 52 (1): 51–8. doi:10.1677/joe.0.0520051. PMID 5061159.

- ^ van Anders SM, Dunn EJ (August 2009). "Are gonadal steroids linked with orgasm perceptions and sexual assertiveness in women and men?". Hormones and Behavior. 56 (2): 206–13. doi:10.1016/j.yhbeh.2009.04.007. hdl:2027.42/83876. PMID 19409392. S2CID 14588630.

- ^ Exton MS, Bindert A, Krüger T, Scheller F, Hartmann U, Schedlowski M (1999). "Cardiovascular and endocrine alterations after masturbation-induced orgasm in women". Psychosomatic Medicine. 61 (3): 280–89. doi:10.1097/00006842-199905000-00005. PMID 10367606.

- ^ Purvis K, Landgren BM, Cekan Z, Diczfalusy E (September 1976). "Endocrine effects of masturbation in men". The Journal of Endocrinology. 70 (3): 439–44. doi:10.1677/joe.0.0700439. PMID 135817.

- ^ Harding SM, Velotta JP (May 2011). "Comparing the relative amount of testosterone required to restore sexual arousal, motivation, and performance in male rats". Hormones and Behavior. 59 (5): 666–73. doi:10.1016/j.yhbeh.2010.09.009. PMID 20920505. S2CID 1577450.

- ^ James PJ, Nyby JG, Saviolakis GA (September 2006). "Sexually stimulated testosterone release in male mice (Mus musculus): roles of genotype and sexual arousal". Hormones and Behavior. 50 (3): 424–31. doi:10.1016/j.yhbeh.2006.05.004. PMID 16828762. S2CID 36436418.

- ^ a b Wallen K (September 2001). "Sex and context: hormones and primate sexual motivation". Hormones and Behavior. 40 (2): 339–57. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.22.5968. doi:10.1006/hbeh.2001.1696. PMID 11534996. S2CID 2214664.

- ^ Hart BL (December 1983). "Role of testosterone secretion and penile reflexes in sexual behavior and sperm competition in male rats: a theoretical contribution". Physiology & Behavior. 31 (6): 823–27. doi:10.1016/0031-9384(83)90279-2. PMID 6665072. S2CID 42155431.

- ^ Kraemer HC, Becker HB, Brodie HK, Doering CH, Moos RH, Hamburg DA (March 1976). "Orgasmic frequency and plasma testosterone levels in normal human males". Archives of Sexual Behavior. 5 (2): 125–32. doi:10.1007/BF01541869. PMID 1275688. S2CID 38283107.

- ^ Roney JR, Mahler SV, Maestripieri D (2003). "Behavioral and hormonal responses of men to brief interactions with women". Evolution and Human Behavior. 24 (6): 365–75. doi:10.1016/S1090-5138(03)00053-9.

- ^ Pirke KM, Kockott G, Dittmar F (November 1974). "Psychosexual stimulation and plasma testosterone in man". Archives of Sexual Behavior. 3 (6): 577–84. doi:10.1007/BF01541140. PMID 4429441. S2CID 43495791.

- ^ Hellhammer DH, Hubert W, Schürmeyer T (1985). "Changes in saliva testosterone after psychological stimulation in men". Psychoneuroendocrinology. 10 (1): 77–81. doi:10.1016/0306-4530(85)90041-1. PMID 4001279. S2CID 41819670.

- ^ Rowland DL, Heiman JR, Gladue BA, Hatch JP, Doering CH, Weiler SJ (1987). "Endocrine, psychological and genital response to sexual arousal in men". Psychoneuroendocrinology. 12 (2): 149–58. doi:10.1016/0306-4530(87)90045-X. PMID 3602262. S2CID 35309934.

- ^ Miller SL, Maner JK (February 2010). "Scent of a woman: men's testosterone responses to olfactory ovulation cues". Psychological Science. 21 (2): 276–83. doi:10.1177/0956797609357733. PMID 20424057. S2CID 18170407.

- ^ Gangestead SW, Thornhill R, Garver-Apgar CE (2005). "Adaptations to Ovulation: Implications for Sexual and Social Behavior". Current Directions in Psychological Science. 14 (6): 312–16. doi:10.1111/j.0963-7214.2005.00388.x. S2CID 53074076.

- ^ Traish AM, Kim N, Min K, Munarriz R, Goldstein I (April 2002). "Role of androgens in female genital sexual arousal: receptor expression, structure, and function". Fertility and Sterility. 77 (Suppl 4): S11–8. doi:10.1016/s0015-0282(02)02978-3. PMID 12007897.

- ^ van Anders SM, Hamilton LD, Schmidt N, Watson NV (April 2007). "Associations between testosterone secretion and sexual activity in women". Hormones and Behavior. 51 (4): 477–82. doi:10.1016/j.yhbeh.2007.01.003. hdl:2027.42/83880. PMID 17320881. S2CID 5718960.

- ^ Tuiten A, Van Honk J, Koppeschaar H, Bernaards C, Thijssen J, Verbaten R (February 2000). "Time course of effects of testosterone administration on sexual arousal in women". Archives of General Psychiatry. 57 (2): 149–53, discussion 155–6. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.57.2.149. PMID 10665617.

- ^ Goldey KL, van Anders SM (May 2011). "Sexy thoughts: effects of sexual cognitions on testosterone, cortisol, and arousal in women" (PDF). Hormones and Behavior. 59 (5): 754–64. doi:10.1016/j.yhbeh.2010.12.005. hdl:2027.42/83874. PMID 21185838. S2CID 18691358.

- ^ a b Bolour S, Braunstein G (2005). "Testosterone therapy in women: a review". International Journal of Impotence Research. 17 (5): 399–408. doi:10.1038/sj.ijir.3901334. PMID 15889125.

- ^ a b Sorokowski P, et al. (October 2019). "Romantic Love and Reproductive Hormones in Women". Int J Environ Res Public Health. 16 (21): 4224. doi:10.3390/ijerph16214224. PMC 6861983. PMID 31683520.

- ^ a b c Marazziti D, Canale D (August 2004). "Hormonal changes when falling in love". Psychoneuroendocrinology. 29 (7): 931–36. doi:10.1016/j.psyneuen.2003.08.006. PMID 15177709. S2CID 24651931.

- ^ a b van Anders SM, Watson NV (July 2006). "Relationship status and testosterone in North American heterosexual and non-heterosexual men and women: cross-sectional and longitudinal data". Psychoneuroendocrinology. 31 (6): 715–23. doi:10.1016/j.psyneuen.2006.01.008. hdl:2027.42/83924. PMID 16621328. S2CID 22477678.

- ^ a b c Booth A, Dabbs JM (1993). "Testosterone and Men's Marriages". Social Forces. 72 (2): 463–77. doi:10.1093/sf/72.2.463.

- ^ Mazur A, Michalek J (1998). "Marriage, Divorce, and Male Testosterone". Social Forces. 77 (1): 315–30. doi:10.1093/sf/77.1.315.

- ^ Gray PB, Chapman JF, Burnham TC, McIntyre MH, Lipson SF, Ellison PT (June 2004). "Human male pair bonding and testosterone". Human Nature. 15 (2): 119–31. doi:10.1007/s12110-004-1016-6. PMID 26190409. S2CID 33812118.

- ^ Gray PB, Campbell BC, Marlowe FW, Lipson SF, Ellison PT (October 2004). "Social variables predict between-subject but not day-to-day variation in the testosterone of US men". Psychoneuroendocrinology. 29 (9): 1153–62. doi:10.1016/j.psyneuen.2004.01.008. PMID 15219639. S2CID 18107730.

- ^ van Anders SM, Watson NV (February 2007). "Testosterone levels in women and men who are single, in long-distance relationships, or same-city relationships". Hormones and Behavior. 51 (2): 286–91. doi:10.1016/j.yhbeh.2006.11.005. hdl:2027.42/83915. PMID 17196592. S2CID 30710035.

- ^ Bribiescas RG, Ellison PT, Gray PB (December 2012). "Male Life History, Reproductive Effort, and the Evolution of the Genus Homo". Current Anthropology. 53 (S6): S424–S435. doi:10.1086/667538. S2CID 83046141.

- ^ Kramer KL, Otárola-Castillo E (July 2015). "When mothers need others: The impact of hominin life history evolution on cooperative breeding". Journal of Human Evolution. 84: 16–24. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2015.01.009. PMID 25843884.

- ^ Gettler LT (July 8, 2014). "Applying socioendocrinology to evolutionary models: fatherhood and physiology". Evolutionary Anthropology. 23 (4): 146–60. doi:10.1002/evan.21412. PMID 25116846. S2CID 438574.

- ^ Nauert R (October 30, 2015). "Parenting Skills Influenced by Testosterone Levels, Empathy". Psych Central. Archived from the original on September 30, 2020. Retrieved December 9, 2018.

- ^ a b Sapienza P, Zingales L, Maestripieri D (September 2009). "Gender differences in financial risk aversion and career choices are affected by testosterone". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 106 (36): 15268–73. Bibcode:2009PNAS..10615268S. doi:10.1073/pnas.0907352106. PMC 2741240. PMID 19706398.

- ^ Apicella CL, Dreber A, Campbell B, Gray PB, Hoffman M, Little AC (November 2008). "Testosterone and financial risk preferences". Evolution and Human Behavior. 29 (6): 384–90. doi:10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2008.07.001.

- ^ a b Wright J, Ellis L, Beaver K (2009). Handbook of crime correlates. San Diego: Academic Press. pp. 208–10. ISBN 978-0-12-373612-3.

- ^ Delville Y, Mansour KM, Ferris CF (July 1996). "Testosterone facilitates aggression by modulating vasopressin receptors in the hypothalamus". Physiology & Behavior. 60 (1): 25–9. doi:10.1016/0031-9384(95)02246-5. PMID 8804638. S2CID 23870320.

- ^ a b c d e Archer J (2006). "Testosterone and human aggression: an evaluation of the challenge hypothesis" (PDF). Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 30 (3): 319–45. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2004.12.007. PMID 16483890. S2CID 26405251. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 9, 2016.

- ^ a b Ellis L, Hoskin AW (2015). "The evolutionary neuroandrogenic theory of criminal behavior expanded". Aggression and Violent Behavior. 24: 61–74. doi:10.1016/j.avb.2015.05.002.

- ^ Hoskin AW, Ellis L (2015). "Fetal Testosterone and Criminality: Test of Evolutionary Neuroandrogenic Theory". Criminology. 53 (1): 54–73. doi:10.1111/1745-9125.12056.

- ^ Perciavalle V, Di Corrado D, Petralia MC, Gurrisi L, Massimino S, Coco M (June 2013). "The second-to-fourth digit ratio correlates with aggressive behavior in professional soccer players". Molecular Medicine Reports. 7 (6): 1733–38. doi:10.3892/mmr.2013.1426. PMC 3694562. PMID 23588344.

- ^ Bailey AA, Hurd PL (March 2005). "Finger length ratio (2D:4D) correlates with physical aggression in men but not in women". Biological Psychology. 68 (3): 215–22. doi:10.1016/j.biopsycho.2004.05.001. PMID 15620791. S2CID 16606349. Lay summary – LiveScience (March 2, 2005).

{{cite journal}}:Cite는 사용되지 않는 매개 변수를 사용합니다.lay-url=(도움말) - ^ Benderlioglu Z, Nelson RJ (December 2004). "Digit length ratios predict reactive aggression in women, but not in men". Hormones and Behavior. 46 (5): 558–64. doi:10.1016/j.yhbeh.2004.06.004. PMID 15555497. S2CID 17464657.

- ^ Liu J, Portnoy J, Raine A (August 2012). "Association between a marker for prenatal testosterone exposure and externalizing behavior problems in children". Development and Psychopathology. 24 (3): 771–82. doi:10.1017/S0954579412000363. PMC 4247331. PMID 22781854.

- ^ Butovskaya M, Burkova V, Karelin D, Fink B (October 1, 2015). "Digit ratio (2D:4D), aggression, and dominance in the Hadza and the Datoga of Tanzania". American Journal of Human Biology. 27 (5): 620–27. doi:10.1002/ajhb.22718. PMID 25824265. S2CID 205303673.

- ^ Joyce CW, Kelly JC, Chan JC, Colgan G, O'Briain D, Mc Cabe JP, Curtin W (November 2013). "Second to fourth digit ratio confirms aggressive tendencies in patients with boxers fractures". Injury. 44 (11): 1636–39. doi:10.1016/j.injury.2013.07.018. PMID 23972912.

- ^ Carré JM, Olmstead NA (February 2015). "Social neuroendocrinology of human aggression: examining the role of competition-induced testosterone dynamics" (PDF). Neuroscience. 286: 171–86. doi:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2014.11.029. PMID 25463514. S2CID 32112035.

- ^ Klinesmith J, Kasser T, McAndrew FT (July 2006). "Guns, testosterone, and aggression: an experimental test of a mediational hypothesis". Psychological Science. 17 (7): 568–71. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.2006.01745.x. PMID 16866740. S2CID 33952211.

- ^ Mcandrew FT (2009). "The Interacting Roles of Testosterone and Challenges to Status in Human Male Aggression" (PDF). Aggression and Violent Behavior. 14 (5): 330–335. doi:10.1016/j.avb.2009.04.006.

- ^ Weierstall R, Moran J, Giebel G, Elbert T (May 1, 2014). "Testosterone reactivity and identification with a perpetrator or a victim in a story are associated with attraction to violence-related cues". International Journal of Law and Psychiatry. 37 (3): 304–12. doi:10.1016/j.ijlp.2013.11.016. PMID 24367977.

- ^ Nguyen TV, McCracken JT, Albaugh MD, Botteron KN, Hudziak JJ, Ducharme S (January 2016). "A testosterone-related structural brain phenotype predicts aggressive behavior from childhood to adulthood". Psychoneuroendocrinology. 63: 109–18. doi:10.1016/j.psyneuen.2015.09.021. PMC 4695305. PMID 26431805.

- ^ Eisenegger C, Naef M, Snozzi R, Heinrichs M, Fehr E (2010). "Prejudice and truth about the effect of testosterone on human bargaining behaviour". Nature. 463 (7279): 356–59. Bibcode:2010Natur.463..356E. doi:10.1038/nature08711. PMID 19997098. S2CID 1305527.

- ^ van Honk J, Montoya ER, Bos PA, van Vugt M, Terburg D (May 2012). "New evidence on testosterone and cooperation". Nature. 485 (7399): E4–5, discussion E5–6. Bibcode:2012Natur.485E...4V. doi:10.1038/nature11136. PMID 22622587. S2CID 4383859.

- ^ Eisenegger C, Naef M, Snozzi R, Heinrichs M, Fehr E (2012). "Eisenegger et al. reply". Nature. 485 (7399): E5–E6. Bibcode:2012Natur.485E...5E. doi:10.1038/nature11137. S2CID 4413138.

- ^ Zak PJ, Kurzban R, Ahmadi S, Swerdloff RS, Park J, Efremidze L, Redwine K, Morgan K, Matzner W (January 1, 2009). "Testosterone administration decreases generosity in the ultimatum game". PLOS ONE. 4 (12): e8330. Bibcode:2009PLoSO...4.8330Z. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0008330. PMC 2789942. PMID 20016825.

- ^ McGinnis MY (December 2004). "Anabolic androgenic steroids and aggression: studies using animal models". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1036: 399–415. Bibcode:2004NYASA1036..399M. doi:10.1196/annals.1330.024. PMID 15817752. S2CID 36368056.

- ^ von der PB, Sarkola T, Seppa K, Eriksson CJ (September 2002). "Testosterone, 5 alpha-dihydrotestosterone and cortisol in men with and without alcohol-related aggression". Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 63 (5): 518–26. doi:10.15288/jsa.2002.63.518. PMID 12380846.

- ^ 골드만 D, 라팔라이넨 J, 오자키 N충동성 질환의 후보 유전자를 직접 분석합니다.Bock G, Goode J, eds.범죄 및 반사회적 행동의 유전학.시바 재단 심포지엄 194.Chichester: John Wiley & Sons; 1996.

- ^ Coccaro E (1996). "Neurotransmitter correlates of impulsive aggression in humans. In: Ferris C, Grisso T, eds. Understanding Aggressive Behaviour inn Children". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 794 (1): 82–89. Bibcode:1996NYASA.794...82C. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1996.tb32511.x. PMID 8853594. S2CID 33226665.

- ^ Finkelstein JW, Susman EJ, Chinchilli VM, Kunselman SJ, D'Arcangelo MR, Schwab J, Demers LM, Liben LS, Lookingbill G, Kulin HE (1997). "Estrogen or testosterone increases self-reported aggressive behaviors in hypogonadal adolescents". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 82 (8): 2433–38. doi:10.1210/jcem.82.8.4165. PMID 9253313.

- ^ Soma KK, Scotti MA, Newman AE, Charlier TD, Demas GE (October 2008). "Novel mechanisms for neuroendocrine regulation of aggression". Frontiers in Neuroendocrinology. 29 (4): 476–89. doi:10.1016/j.yfrne.2007.12.003. PMID 18280561. S2CID 32650274.

- ^ Soma KK, Sullivan KA, Tramontin AD, Saldanha CJ, Schlinger BA, Wingfield JC (2000). "Acute and chronic effects of an aromatase inhibitor on territorial aggression in breeding and nonbreeding male song sparrows". Journal of Comparative Physiology A. 186 (7–8): 759–69. doi:10.1007/s003590000129. PMID 11016791. S2CID 23990605.

- ^ McGinnis MY, Lumia AR, Breuer ME, Possidente B (February 2002). "Physical provocation potentiates aggression in male rats receiving anabolic androgenic steroids". Hormones and Behavior. 41 (1): 101–10. doi:10.1006/hbeh.2001.1742. PMID 11863388. S2CID 29969145.

- ^ Sapolsky RM (2018). "Doubled-Edged Swords in the Biology of Conflict". Frontiers in Psychology. 9: 2625. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02625. PMC 6306482. PMID 30619017.

- ^ Sapolsky RM (1998). The trouble with testosterone. New York: Simon and Schuster. pp. 153–55. ISBN 978-0-684-83891-5.

- ^ Eisenegger C, Haushofer J, Fehr E (June 2011). "The role of testosterone in social interaction". Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 15 (6): 263–71. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2011.04.008. PMID 21616702. S2CID 9554219.

- ^ Wilson JD (September 2001). "Androgens, androgen receptors, and male gender role behavior". Review. Hormones and Behavior. 40 (2): 358–66. doi:10.1006/hbeh.2001.1684. PMID 11534997. S2CID 20480423.

- ^ Cosgrove KP, Mazure CM, Staley JK (October 2007). "Evolving knowledge of sex differences in brain structure, function, and chemistry". Biological Psychiatry. 62 (8): 847–55. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.03.001. PMC 2711771. PMID 17544382.

- ^ Marner L, Nyengaard JR, Tang Y, Pakkenberg B (July 2003). "Marked loss of myelinated nerve fibers in the human brain with age". The Journal of Comparative Neurology. 462 (2): 144–52. doi:10.1002/cne.10714. PMID 12794739. S2CID 35293796.

- ^ Bhasin S, Storer TW, Berman N, Callegari C, Clevenger B, Phillips J, Bunnell TJ, Tricker R, Shirazi A, Casaburi R (July 1996). "The effects of supraphysiologic doses of testosterone on muscle size and strength in normal men". The New England Journal of Medicine. 335 (1): 1–7. doi:10.1056/NEJM199607043350101. PMID 8637535. S2CID 73721690.

- ^ "Testosterone Affects Some Women's Career Choices". NPR. August 28, 2009.

- ^ Pike CJ, Rosario ER, Nguyen TV (April 2006). "Androgens, aging, and Alzheimer's disease". Endocrine. 29 (2): 233–41. doi:10.1385/ENDO:29:2:233. PMID 16785599. S2CID 13852805.

- ^ Rosario ER, Chang L, Stanczyk FZ, Pike CJ (September 2004). "Age-related testosterone depletion and the development of Alzheimer disease". JAMA. 292 (12): 1431–32. doi:10.1001/jama.292.12.1431-b. PMID 15383512.

- ^ Hogervorst E, Bandelow S, Combrinck M, Smith AD (2004). "Low free testosterone is an independent risk factor for Alzheimer's disease". Experimental Gerontology. 39 (11–12): 1633–39. doi:10.1016/j.exger.2004.06.019. PMID 15582279. S2CID 24803152.

- ^ Moffat SD, Zonderman AB, Metter EJ, Kawas C, Blackman MR, Harman SM, Resnick SM (January 2004). "Free testosterone and risk for Alzheimer disease in older men". Neurology. 62 (2): 188–93. doi:10.1212/WNL.62.2.188. PMID 14745052. S2CID 10302839.

- ^ Moffat SD, Hampson E (April 1996). "A curvilinear relationship between testosterone and spatial cognition in humans: possible influence of hand preference". Psychoneuroendocrinology. 21 (3): 323–37. doi:10.1016/0306-4530(95)00051-8. PMID 8817730. S2CID 7135870.

- ^ a b c d Bianchi VE (January 2019). "The Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Testosterone". Journal of the Endocrine Society. 3 (1): 91–107. doi:10.1210/js.2018-00186. PMC 6299269. PMID 30582096.

- ^ Krysiak R, Kowalcze K, Okopień B (October 2019). "The effect of testosterone on thyroid autoimmunity in euthyroid men with Hashimoto's thyroiditis and low testosterone levels". Journal of Clinical Pharmacy and Therapeutics. 44 (5): 742–749. doi:10.1111/jcpt.12987. PMID 31183891. S2CID 184487697.

- ^ "List of Gender Dysphoria Medications (6 Compared)". Drugs.com. Retrieved May 6, 2020.

- ^ Myers JB, Meacham RB (2003). "Androgen replacement therapy in the aging male". Reviews in Urology. 5 (4): 216–26. PMC 1508369. PMID 16985841.

- ^ Staff (March 3, 2015). "Testosterone Products: Drug Safety Communication – FDA Cautions About Using Testosterone Products for Low Testosterone Due to Aging; Requires Labeling Change to Inform of Possible Increased Risk of Heart Attack And Stroke". FDA. Retrieved March 5, 2015.

- ^ "19th WHO Model List of Essential Medicines (April 2015)" (PDF). WHO. April 2015. Retrieved May 10, 2015.

- ^ Qaseem A, Horwitch CA, Vijan S, Etxeandia-Ikobaltzeta I, Kansagara D (January 2020). "Testosterone Treatment in Adult Men With Age-Related Low Testosterone: A Clinical Guideline From the American College of Physicians". Annals of Internal Medicine. 172 (2): 126–133. doi:10.7326/M19-0882. PMID 31905405.

- ^ Parry NM (January 7, 2020). "New Guideline for Testosterone Treatment in Men With 'Low T'". Medscape.com. Retrieved January 7, 2020.

- ^ Bikle DD (January 2021). "The Free Hormone Hypothesis: When, Why, and How to Measure the Free Hormone Levels to Assess Vitamin D, Thyroid, Sex Hormone, and Cortisol Status". JBMR Plus. 5 (1): e10418. doi:10.1002/jbm4.10418. PMC 7839820. PMID 33553985.

- ^ Hiipakka RA, Liao S (October 1998). "Molecular mechanism of androgen action". Trends in Endocrinology and Metabolism. 9 (8): 317–24. doi:10.1016/S1043-2760(98)00081-2. PMID 18406296. S2CID 23385663.

- ^ McPhaul MJ, Young M (September 2001). "Complexities of androgen action". Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 45 (3 Suppl): S87–94. doi:10.1067/mjd.2001.117429. PMID 11511858.

- ^ Bennett NC, Gardiner RA, Hooper JD, Johnson DW, Gobe GC (2010). "Molecular cell biology of androgen receptor signalling". Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 42 (6): 813–27. doi:10.1016/j.biocel.2009.11.013. PMID 19931639.

- ^ Wang C, Liu Y, Cao JM (2014). "G protein-coupled receptors: extranuclear mediators for the non-genomic actions of steroids". Int J Mol Sci. 15 (9): 15412–25. doi:10.3390/ijms150915412. PMC 4200746. PMID 25257522.

- ^ Lang F, Alevizopoulos K, Stournaras C (2013). "Targeting membrane androgen receptors in tumors". Expert Opin. Ther. Targets. 17 (8): 951–63. doi:10.1517/14728222.2013.806491. PMID 23746222. S2CID 23918273.

- ^ Breiner M, Romalo G, Schweikert HU (August 1986). "Inhibition of androgen receptor binding by natural and synthetic steroids in cultured human genital skin fibroblasts". Klinische Wochenschrift. 64 (16): 732–37. doi:10.1007/BF01734339. PMID 3762019. S2CID 34846760.

- ^ Kelly MJ, Qiu J, Rønnekleiv OK (January 1, 2005). Estrogen signaling in the hypothalamus. Vitamins & Hormones. Vol. 71. pp. 123–45. doi:10.1016/S0083-6729(05)71005-0. ISBN 9780127098715. PMID 16112267.

- ^ McCarthy MM (2008). "Estradiol and the developing brain". Physiological Reviews. 88 (1): 91–124. doi:10.1152/physrev.00010.2007. PMC 2754262. PMID 18195084.

- ^ Kohtz AS, Frye CA (2012). "Dissociating behavioral, autonomic, and neuroendocrine effects of androgen steroids in animal models". Psychiatric Disorders. Methods in Molecular Biology. Vol. 829. pp. 397–431. doi:10.1007/978-1-61779-458-2_26. ISBN 978-1-61779-457-5. PMID 22231829.

- ^ a b Prough RA, Clark BJ, Klinge CM (2016). "Novel mechanisms for DHEA action". J. Mol. Endocrinol. 56 (3): R139–55. doi:10.1530/JME-16-0013. PMID 26908835.

- ^ a b Lazaridis I, Charalampopoulos I, Alexaki VI, Avlonitis N, Pediaditakis I, Efstathopoulos P, Calogeropoulou T, Castanas E, Gravanis A (2011). "Neurosteroid dehydroepiandrosterone interacts with nerve growth factor (NGF) receptors, preventing neuronal apoptosis". PLOS Biol. 9 (4): e1001051. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1001051. PMC 3082517. PMID 21541365.

- ^ a b Gravanis A, Calogeropoulou T, Panoutsakopoulou V, Thermos K, Neophytou C, Charalampopoulos I (2012). "Neurosteroids and microneurotrophins signal through NGF receptors to induce prosurvival signaling in neuronal cells". Sci Signal. 5 (246): pt8. doi:10.1126/scisignal.2003387. PMID 23074265. S2CID 26914550.

- ^ Albayrak Y, Hashimoto K (2017). "Sigma-1 Receptor Agonists and Their Clinical Implications in Neuropsychiatric Disorders". Sigma Receptors: Their Role in Disease and as Therapeutic Targets. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology. Vol. 964. pp. 153–161. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-50174-1_11. ISBN 978-3-319-50172-7. PMID 28315270.

- ^ Regitz-Zagrosek V (October 2, 2012). Sex and Gender Differences in Pharmacology. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 245–. ISBN 978-3-642-30725-6.

- ^ Häggström M, Richfield D (2014). "Diagram of the pathways of human steroidogenesis". WikiJournal of Medicine. 1 (1). doi:10.15347/wjm/2014.005.

- ^ Waterman MR, Keeney DS (1992). "Genes involved in androgen biosynthesis and the male phenotype". Hormone Research. 38 (5–6): 217–21. doi:10.1159/000182546. PMID 1307739.

- ^ Zuber MX, Simpson ER, Waterman MR (December 1986). "Expression of bovine 17 alpha-hydroxylase cytochrome P-450 cDNA in nonsteroidogenic (COS 1) cells". Science. 234 (4781): 1258–61. Bibcode:1986Sci...234.1258Z. doi:10.1126/science.3535074. PMID 3535074.

- ^ Zouboulis CC, Degitz K (2004). "Androgen action on human skin – from basic research to clinical significance". Experimental Dermatology. 13 (Suppl 4): 5–10. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0625.2004.00255.x. PMID 15507105. S2CID 34863608.

- ^ Brooks RV (November 1975). "Androgens". Clinics in Endocrinology and Metabolism. 4 (3): 503–20. doi:10.1016/S0300-595X(75)80045-4. PMID 58744.

- ^ Payne AH, O'Shaughnessy P (1996). "Structure, function, and regulation of steroidogenic enzymes in the Leydig cell". In Payne AH, Hardy MP, Russell LD (eds.). Leydig Cell. Vienna [Il]: Cache River Press. pp. 260–85. ISBN 978-0-9627422-7-9.

- ^ Swerdloff RS, Wang C, Bhasin S (April 1992). "Developments in the control of testicular function". Baillière's Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 6 (2): 451–83. doi:10.1016/S0950-351X(05)80158-2. PMID 1377467.

- ^ Liverman CT, Blazer DG, et al. (Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Assessing the Need for Clinical Trials of Testosterone Replacement Therapy) (January 1, 2004). "Introduction". Testosterone and Aging: Clinical Research Directions. National Academies Press (US). doi:10.17226/10852. ISBN 978-0-309-09063-6. PMID 25009850 – via www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov.

- ^ Huhtaniemi I (2014). "Late-onset hypogonadism: current concepts and controversies of pathogenesis, diagnosis and treatment". Asian Journal of Andrology. 16 (2): 192–202. doi:10.4103/1008-682X.122336. PMC 3955328. PMID 24407185.

- ^ Huhtaniemi IT (2014). "Andropause--lessons from the European Male Ageing Study". Annales d'Endocrinologie. 75 (2): 128–31. doi:10.1016/j.ando.2014.03.005. PMID 24793989.

- ^ Vingren JL, Kraemer WJ, Ratamess NA, Anderson JM, Volek JS, Maresh CM (2010). "Testosterone physiology in resistance exercise and training: the up-stream regulatory elements". Sports Medicine. 40 (12): 1037–53. doi:10.2165/11536910-000000000-00000. PMID 21058750. S2CID 11683565.

- ^ Hulmi JJ, Ahtiainen JP, Selänne H, Volek JS, Häkkinen K, Kovanen V, Mero AA (May 2008). "Androgen receptors and testosterone in men—effects of protein ingestion, resistance exercise and fiber type". The Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. 110 (1–2): 130–37. doi:10.1016/j.jsbmb.2008.03.030. PMID 18455389. S2CID 26280370.

- ^ Hackney AC, Moore AW, Brownlee KK (2005). "Testosterone and endurance exercise: development of the "exercise-hypogonadal male condition"". Acta Physiologica Hungarica. 92 (2): 121–37. doi:10.1556/APhysiol.92.2005.2.3. PMID 16268050.

- ^ Livera G, Rouiller-Fabre V, Pairault C, Levacher C, Habert R (August 2002). "Regulation and perturbation of testicular functions by vitamin A". Reproduction. 124 (2): 173–180. doi:10.1530/rep.0.1240173. PMID 12141930.

- ^ Pilz S, Frisch S, Koertke H, Kuhn J, Dreier J, Obermayer-Pietsch B, et al. (March 2011). "Effect of vitamin D supplementation on testosterone levels in men". Hormone and Metabolic Research = Hormon- Und Stoffwechselforschung = Hormones Et Metabolisme. 43 (3): 223–225. doi:10.1055/s-0030-1269854. PMID 21154195. S2CID 206315145.

- ^ Prasad AS, Mantzoros CS, Beck FW, Hess JW, Brewer GJ (May 1996). "Zinc status and serum testosterone levels of healthy adults". Nutrition. 12 (5): 344–348. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.551.4971. doi:10.1016/S0899-9007(96)80058-X. PMID 8875519.

- ^ Koehler K, Parr MK, Geyer H, Mester J, Schänzer W (January 2009). "Serum testosterone and urinary excretion of steroid hormone metabolites after administration of a high-dose zinc supplement". European Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 63 (1): 65–70. doi:10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602899. PMID 17882141.

- ^ Whittaker J, Wu K (June 2021). "Low-fat diets and testosterone in men: Systematic review and meta-analysis of intervention studies". The Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. 210: 105878. arXiv:2204.00007. doi:10.1016/j.jsbmb.2021.105878. PMID 33741447. S2CID 232246357.

- ^ Whittaker J, Harris M (March 2022). "Low-carbohydrate diets and men's cortisol and testosterone: Systematic review and meta-analysis". Nutrition and Health: 2601060221083079. doi:10.1177/02601060221083079. PMID 35254136. S2CID 247251547.

- ^ Håkonsen LB, Thulstrup AM, Aggerholm AS, Olsen J, Bonde JP, Andersen CY, Bungum M, Ernst EH, Hansen ML, Ernst EH, Ramlau-Hansen CH (2011). "Does weight loss improve semen quality and reproductive hormones? Results from a cohort of severely obese men". Reproductive Health. 8 (1): 24. doi:10.1186/1742-4755-8-24. PMC 3177768. PMID 21849026.

- ^ MacDonald AA, Herbison GP, Showell M, Farquhar CM (2010). "The impact of body mass index on semen parameters and reproductive hormones in human males: a systematic review with meta-analysis". Human Reproduction Update. 16 (3): 293–311. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmp047. PMID 19889752.

- ^ Andersen ML, Tufik S (October 2008). "The effects of testosterone on sleep and sleep-disordered breathing in men: its bidirectional interaction with erectile function". Sleep Medicine Reviews. 12 (5): 365–79. doi:10.1016/j.smrv.2007.12.003. PMID 18519168.

- ^ Schultheiss OC, Campbell KL, McClelland DC (December 1999). "Implicit power motivation moderates men's testosterone responses to imagined and real dominance success". Hormones and Behavior. 36 (3): 234–41. doi:10.1006/hbeh.1999.1542. PMID 10603287. S2CID 6002474.

- ^ Akdoğan M, Tamer MN, Cüre E, Cüre MC, Köroğlu BK, Delibaş N (May 2007). "Effect of spearmint (Mentha spicata Labiatae) teas on androgen levels in women with hirsutism". Phytotherapy Research. 21 (5): 444–47. doi:10.1002/ptr.2074. PMID 17310494. S2CID 21961390.

- ^ Kumar V, Kural MR, Pereira BM, Roy P (December 2008). "Spearmint induced hypothalamic oxidative stress and testicular anti-androgenicity in male rats - altered levels of gene expression, enzymes and hormones". Food and Chemical Toxicology. 46 (12): 3563–70. doi:10.1016/j.fct.2008.08.027. PMID 18804513.

- ^ Grant P (February 2010). "Spearmint herbal tea has significant anti-androgen effects in polycystic ovarian syndrome. A randomized controlled trial". Phytotherapy Research. 24 (2): 186–88. doi:10.1002/ptr.2900. PMID 19585478. S2CID 206425734.

- ^ Armanini D, Fiore C, Mattarello MJ, Bielenberg J, Palermo M (September 2002). "History of the endocrine effects of licorice". Experimental and Clinical Endocrinology & Diabetes. 110 (6): 257–61. doi:10.1055/s-2002-34587. PMID 12373628.

- ^ Nieschlag E, Behre HM, Nieschlag S (July 26, 2012). Testosterone: Action, Deficiency, Substitution. Cambridge University Press. pp. 61–. ISBN 978-1-107-01290-5.

- ^ Cumming DC, Wall SR (November 1985). "Non-sex hormone-binding globulin-bound testosterone as a marker for hyperandrogenism". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 61 (5): 873–6. doi:10.1210/jcem-61-5-873. PMID 4044776.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Becker KL (2001). Principles and Practice of Endocrinology and Metabolism. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 1116, 1119, 1183. ISBN 978-0-7817-1750-2.

- ^ a b c d Wecker L, Watts S, Faingold C, Dunaway G, Crespo L (April 1, 2009). Brody's Human Pharmacology. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 468–469. ISBN 978-0-323-07575-6.

- ^ Penning TM (2010). "New frontiers in androgen biosynthesis and metabolism". Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 17 (3): 233–9. doi:10.1097/MED.0b013e3283381a31. PMC 3206266. PMID 20186052.

- ^ Horsky J, Presl J (December 6, 2012). Ovarian Function and its Disorders: Diagnosis and Therapy. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 107–. ISBN 978-94-009-8195-9.

- ^ a b c d e Zhou S (April 6, 2016). Cytochrome P450 2D6: Structure, Function, Regulation and Polymorphism. CRC Press. pp. 242–. ISBN 978-1-4665-9788-4.

- ^ Trager L (1977). Steroidhormone: Biosynthese, Stoffwechsel, Wirkung (in German). Springer-Verlag. p. 349. ISBN 978-0-387-08012-3.

- ^ Randall VA (April 1994). "Role of 5 alpha-reductase in health and disease". Baillière's Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 8 (2): 405–31. doi:10.1016/S0950-351X(05)80259-9. PMID 8092979.

- ^ Meinhardt U, Mullis PE (August 2002). "The essential role of the aromatase/p450arom". Seminars in Reproductive Medicine. 20 (3): 277–84. doi:10.1055/s-2002-35374. PMID 12428207.

- ^ Noakes DE (April 23, 2009). Arthur's Veterinary Reproduction and Obstetrics. Elsevier Health Sciences UK. pp. 695–. ISBN 978-0-7020-3990-4.

- ^ Nieschlag E, Behre HM (April 1, 2004). Testosterone: Action, Deficiency, Substitution. Cambridge University Press. pp. 626–. ISBN 978-1-139-45221-2.

- ^ Parl FF (2000). Estrogens, Estrogen Receptor and Breast Cancer. IOS Press. pp. 25–. ISBN 978-0-9673355-4-4.

- ^ Norman AW, Henry HL (July 30, 2014). Hormones. Academic Press. pp. 261–. ISBN 978-0-08-091906-5.

- ^ Mozayani A, Raymon L (September 18, 2011). Handbook of Drug Interactions: A Clinical and Forensic Guide. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 656–. ISBN 978-1-61779-222-9.

- ^ Sundaram K, Kumar N, Monder C, Bardin CW (1995). "Different patterns of metabolism determine the relative anabolic activity of 19-norandrogens". J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 53 (1–6): 253–7. doi:10.1016/0960-0760(95)00056-6. PMID 7626464. S2CID 32619627.

- ^ a b Travison TG, Vesper HW, Orwoll E, Wu F, Kaufman JM, Wang Y, et al. (April 2017). "Harmonized Reference Ranges for Circulating Testosterone Levels in Men of Four Cohort Studies in the United States and Europe". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 102 (4): 1161–1173. doi:10.1210/jc.2016-2935. PMC 5460736. PMID 28324103.

- ^ a b Sperling MA (April 10, 2014). Pediatric Endocrinology E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 488–. ISBN 978-1-4557-5973-6.

- ^ "Testosterone, total". LabCorp. Retrieved December 20, 2021.

- ^ Morgentaler A (May 2017). "Andrology: Testosterone reference ranges and diagnosis of testosterone deficiency". Nature Reviews. Urology. 14 (5): 263–264. doi:10.1038/nrurol.2017.35. PMID 28266512. S2CID 29122481.

- ^ Morgentaler A, Khera M, Maggi M, Zitzmann M (July 2014). "Commentary: Who is a candidate for testosterone therapy? A synthesis of international expert opinions". The Journal of Sexual Medicine. 11 (7): 1636–1645. doi:10.1111/jsm.12546. PMID 24797325.

- ^ Wang C, Nieschlag E, Swerdloff R, Behre HM, Hellstrom WJ, Gooren LJ, et al. (October 16, 208). "ISA, ISSAM, EAU, EAA and ASA recommendations: investigation, treatment and monitoring of late-onset hypogonadism in males". International Journal of Impotence Research. 21 (1): 1–8. doi:10.1038/ijir.2008.41. PMID 18923415. S2CID 30430279.

- ^ Bhasin S, Pencina M, Jasuja GK, Travison TG, Coviello A, Orwoll E, et al. (August 2011). "Reference ranges for testosterone in men generated using liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry in a community-based sample of healthy nonobese young men in the Framingham Heart Study and applied to three geographically distinct cohorts". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 96 (8): 2430–2439. doi:10.1210/jc.2010-3012. PMC 3146796. PMID 21697255.

- ^ a b Camacho PM (September 26, 2012). Evidence-Based Endocrinology. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 217–. ISBN 978-1-4511-7146-4.

- ^ a b Steinberger E, Ayala C, Hsi B, Smith KD, Rodriguez-Rigau LJ, Weidman ER, Reimondo GG (1998). "Utilization of commercial laboratory results in management of hyperandrogenism in women". Endocrine Practice. 4 (1): 1–10. doi:10.4158/EP.4.1.1. PMID 15251757.

- ^ Bajaj L, Berman S (January 1, 2011). Berman's Pediatric Decision Making. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 160–. ISBN 978-0-323-05405-8.

- ^ Styne DM (April 25, 2016). Pediatric Endocrinology: A Clinical Handbook. Springer. pp. 191–. ISBN 978-3-319-18371-8.

- ^ Pagana KD, Pagana TJ, Pagana TN (September 19, 2014). Mosby's Diagnostic and Laboratory Test Reference – E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 879–. ISBN 978-0-323-22592-2.

- ^ Engorn B, Flerlage J (May 1, 2014). The Harriet Lane Handbook E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 240–. ISBN 978-0-323-11246-8.

- ^ de Ronde W, van der Schouw YT, Pols HA, Gooren LJ, Muller M, Grobbee DE, de Jong FH (September 2006). "Calculation of bioavailable and free testosterone in men: a comparison of 5 published algorithms". Clinical Chemistry. 52 (9): 1777–84. doi:10.1373/clinchem.2005.063354. PMID 16793931.

- ^ Hasler J, Herklotz R, Luppa PB, Diver MJ, Thevis M, Metzger J, Savoca R, Jermini F, Huber AR (January 1, 2006). "Impact of recent biochemical findings on the determination of free and bioavailable testosterone: evaluation and proposal for clinical use". LaboratoriumsMedizin. 30 (6): 492–505. doi:10.1515/JLM.2006.050.

- ^ "RCSB PDB - 1D2S". Crystal Structure of the N-Terminal Laminin G-Like Domain of SHBG in Complex with Dihydrotestosterone.

- ^ Berthold AA (1849). "Transplantation der Hoden" [Transplantation of testis]. Arch. Anat. Physiol. Wiss. (in German). 16: 42–6.

- ^ Brown-Sequard CE (1889). "The effects produced on man by subcutaneous injections of liquid obtained from the testicles of animals". Lancet. 2 (3438): 105–07. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(00)64118-1.

- ^ Gallagher TF, Koch FC (November 1929). "The testicular hormone". J. Biol. Chem. 84 (2): 495–500. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(18)77008-7.

- ^ David KG, Dingemanse E, Freud JL (May 1935). "Über krystallinisches mannliches Hormon aus Hoden (Testosteron) wirksamer als aus harn oder aus Cholesterin bereitetes Androsteron" [On crystalline male hormone from testicles (testosterone) effective as from urine or from cholesterol]. Hoppe-Seyler's Z Physiol Chem (in German). 233 (5–6): 281–83. doi:10.1515/bchm2.1935.233.5-6.281.

- ^ Butenandt A, Hanisch G (1935). "Umwandlung des Dehydroandrosterons in Androstendiol und Testosterone; ein Weg zur Darstellung des Testosterons aus Cholestrin" [About Testosterone. Conversion of Dehydro-androsterons into androstendiol and testosterone; a way for the structure assignment of testosterone from cholesterol]. Hoppe-Seyler's Z Physiol Chem (in German). 237 (2): 89–97. doi:10.1515/bchm2.1935.237.1-3.89.

- ^ a b Freeman ER, Bloom DA, McGuire EJ (February 2001). "A brief history of testosterone". The Journal of Urology. 165 (2): 371–73. doi:10.1097/00005392-200102000-00004. PMID 11176375.

- ^ Butenandt A, Hanisch G (1935). "Uber die Umwandlung des Dehydroandrosterons in Androstenol-(17)-one-(3) (Testosterone); um Weg zur Darstellung des Testosterons auf Cholesterin (Vorlauf Mitteilung). [The conversion of dehydroandrosterone into androstenol-(17)-one-3 (testosterone); a method for the production of testosterone from cholesterol (preliminary communication)]". Chemische Berichte (in German). 68 (9): 1859–62. doi:10.1002/cber.19350680937.

- ^ Ruzicka L, Wettstein A (1935). "Uber die kristallinische Herstellung des Testikelhormons, Testosteron (Androsten-3-ol-17-ol) [The crystalline production of the testicle hormone, testosterone (Androsten-3-ol-17-ol)]". Helvetica Chimica Acta (in German). 18: 1264–75. doi:10.1002/hlca.193501801176.

- ^ Hoberman JM, Yesalis CE (February 1995). "The history of synthetic testosterone". Scientific American. 272 (2): 76–81. Bibcode:1995SciAm.272b..76H. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0295-76. PMID 7817189.

- ^ Kenyon AT, Knowlton K, Sandiford I, Koch FC, Lotwin, G (February 1940). "A comparative study of the metabolic effects of testosterone propionate in normal men and women and in eunuchoidism". Endocrinology. 26 (1): 26–45. doi:10.1210/Endo-26-1-26.

- ^ Schwarz S, Onken D, Schubert A (July 1999). "The steroid story of Jenapharm: from the late 1940s to the early 1970s". Steroids. 64 (7): 439–45. doi:10.1016/S0039-128X(99)00003-3. PMID 10443899. S2CID 40156824.

- ^ de Kruif P (1945). The Male Hormone. New York: Harcourt, Brace.

- ^ Guerriero G (2009). "Vertebrate sex steroid receptors: evolution, ligands, and neurodistribution". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1163 (1): 154–68. Bibcode:2009NYASA1163..154G. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.04460.x. PMID 19456336. S2CID 5790990.

- ^ Bryan MB, Scott AP, Li W (2008). "Sex steroids and their receptors in lampreys". Steroids. 73 (1): 1–12. doi:10.1016/j.steroids.2007.08.011. PMID 17931674. S2CID 33753909.

- ^ Nelson RF (2005). An introduction to behavioral endocrinology. Sunderland, Mass: Sinauer Associates. p. 143. ISBN 978-0-87893-617-5.

- ^ De Loof A (October 2006). "Ecdysteroids: the overlooked sex steroids of insects? Males: the black box". Insect Science. 13 (5): 325–338. doi:10.1111/j.1744-7917.2006.00101.x. S2CID 221810929.

- ^ Mechoulam R, Brueggemeier RW, Denlinger DL (September 1984). "Estrogens in insects". Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences. 40 (9): 942–44. doi:10.1007/BF01946450. S2CID 31950471.

추가 정보

- Fargo KN, Pak TR, Foecking EM, Jones KJ (2010). "Molecular Biology of Androgen Action: Perspectives on Neuroprotective and Neurotherapeutic Effects.". In Pfaff DW, Etgen AM (eds.). Molecular Mechanisms of Hormone Actions on Behavior. Elsevier Inc. pp. 1219–1246. doi:10.1016/B978-008088783-8.00036-X. ISBN 978-0-12-374939-0.

- Dowd NE (2013). "Sperm, testosterone, masculinities and fatherhood". Nevada Law Journal. 13 (2): 8.

- Celec P, Ostatníková D, Hodosy J (February 2015). "On the effects of testosterone on brain behavioral functions". Frontiers in Neuroscience. 9: 12. doi:10.3389/fnins.2015.00012. PMC 4330791. PMID 25741229.